Version française abrégée

Dans les régions méditerranéennes, les systèmes fluviaux ont été particulièrement réactifs aux variations des paramètres environnementaux du Quaternaire : tectonique, climat, et activités humaines précoces dans ces régions [7,22,23,42]. Les phases d’alluvionnement ou d’incision sont généralement interprétées en termes climatiques : l’accrétion sédimentaire est attribuée à des périodes, soit d’aridité [15,21], soit d’humidité [1,41], soit de transition aride–humide [40]. L’impact anthropique n’est évoqué que pour les deux ou trois derniers millénaires [1,7,40]. Les observations lithologiques et morphologiques effectuées sur la basse vallée de l’oued Kert au Maroc nord-oriental, calées chronologiquement grâce à 16 datations 14C, ont montré la succession d’importantes phases d’incision et de sédimentation au cours du Pléistocène récent et de l’Holocène. Cette note vise à décrire ces fluctuations et à en interpréter l’origine.

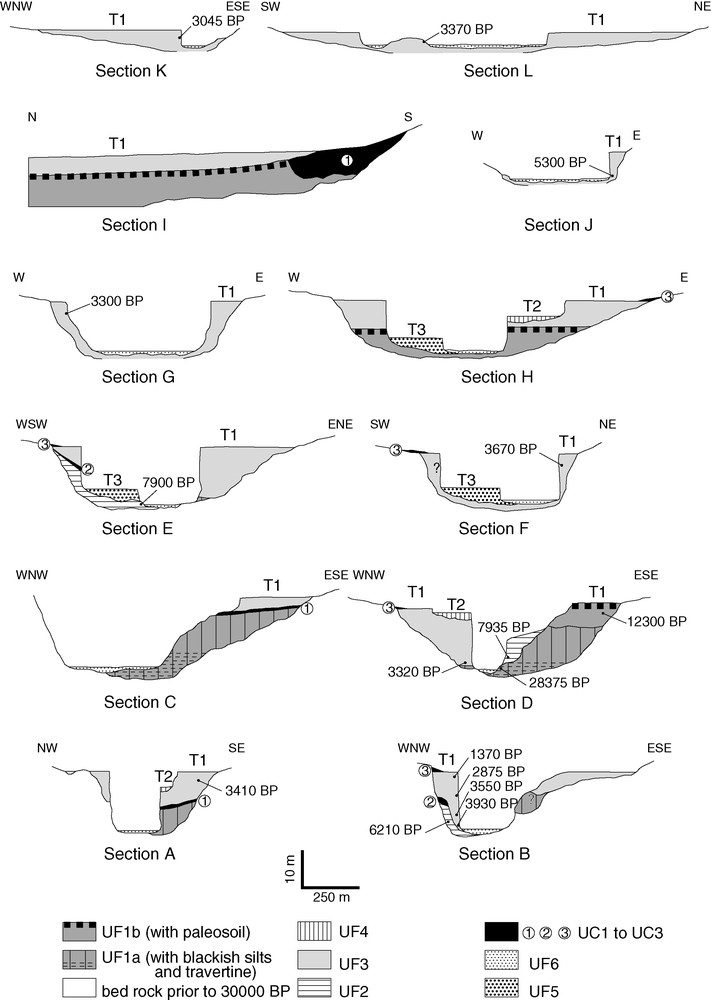

L’oued Kert se trouve à l’ouest de Nador (Fig. 1). Son bassin versant (2873 km2) s’élève jusqu’à 1800 m d’altitude dans le Rif, en domaine surtout sédimentaire. Le climat est méditerranéen semi-aride, et la végétation très clairsemée [36]. Cette étude porte sur les 30 derniers kilomètres de l’oued. Son cours sinueux suit des accidents structuraux majeurs (Fig. 1). Plusieurs niveaux de terrasses alluviales quaternaires ont été décrits dont une terrasse majeure attribuée à l’Holocène [5,6]. De grandes coupes dégagées par l’érosion ont pu y être étudiées. Six unités alluviales, notées UF1 à UF6, de la plus ancienne à la plus récente, comprenant 18 lithofaciès, et trois unités colluviales (UC1 à UC3) intercalées entre les unités alluviales, ont été identifiées (Fig. 2). Elles sont séparées par six phases d’incision (I1 à I6). Cette évolution a engendré trois terrasses alluviales : T1 est la terrasse majeure, haute de 20 m au-dessus du lit de l’oued en amont et 0 m en aval ; T2 et T3 sont situées en contrebas. Les datations 14C s’échelonnent entre 28 375 ± 450 et 1370 ± 40 ans 14C BP (Tableau 1).

Lower Kert River valley: location, geological and morphological data: (1) basement; (2) T1 alluvial terrace (Late Pleistocene and Holocene); (3) T2 alluvial terrace (Upper Holocene); (4) T3 alluvial terrace (Upper Holocene); (5) present alluvium; (6) faults (according to [5]); (7) sections of Fig. 2.

La basse vallée de l’oued Kert : localisation, données géologiques et morphologiques. (1) substrat ; (2) terrasse alluviale T1 (Pléistocène récent et Holocène) ; (3) terrasse alluviale T2 (Holocène supérieur) ; (4) terrasse alluviale T3 (Holocène supérieur) ; (5) alluvions actuelles ; (6) failles (d’après[5]) ; (7) coupes de laFig. 2.

Distribution of lithological units in A to L cross sections (location of sections, see Fig. 1). UF1 to UF6: alluvial units; UC1 to UC3: colluvial units; T1 to T3: alluvial terraces; 3410 BP: age in 14C a BP.

Distribution des unités lithologiques dans les coupes transversales A à L (localisation des coupes, voirFig. 1). UF1 à UF6 : unités alluviales ; UC1 à UC3 : unités colluviales ; T1 à T3 terrasses alluviales ; 3410 BP : âge en années 14C BP.

Au Pléistocène récent, l’accrétion de l’UF1, commencée un peu avant 28 375 ± 450 ans 14C BP et terminée un peu après 12 300 ± 155 ans 14C BP, s’est effectuée en deux phases (UF1a et UF1b), séparées par une période de stabilité ou de légère incision (I1), non datée, en contexte de forte régression marine [16,27]. La sédimentation dominante indique une forte production sédimentaire, sans doute favorisée par la couverture végétale généralement herbacée sous climat frais et humide [8,20]. Le bas niveau marin ne paraît pas avoir réduit la capacité de stockage sédimentaire dans la basse vallée, la sédimentation ayant peut-être été favorisée par la subsidence (tronçons I et II), comme suggéré par [5]. Les faciès sédimentaires traduisent deux épisodes à hydrologie régulière, probablement humides, l’un dans la partie inférieure d’UF1a, confirmé par les données palynologiques [6], et l’autre à la partie supérieure d’UF1b. Ils encadrent des faciès indiquant des écoulements plus irréguliers dans UF1a et UF1b, parfois de forte énergie, avec des épisodes prolongés d’arrêt de sédimentation (formation de croûtes calcaires). Ces caractères hydrologiques paraissent en accord avec l’évolution climatique - phase plus humide vers 30 000 ans, phase plus sèche après 20 000 ans 14C BP, augmentation de l’humidité vers 14 000 ans 14C BP – reconnue en Méditerranée occidentale [1,8,17,20,31,32].

La phase d’incision majeure I2, développée au Pléistocène récent après 12 300 ans 14C BP et à l’Holocène inférieur avant 7935 ans 14C BP en contexte de forte remontée eustatique [11,27], est générale au Maroc [5,30,37,38,41]. Le couvert végétal steppique développé sous climat aride [4,8,20,31] et plus chaud après 10 000 ans 14C BP [12] ayant été favorable à la production sédimentaire, seule une hydrologie irrégulière et temporairement énergique peut expliquer l’évacuation de la matière vers la mer et l’incision profonde dans les alluvions UF1.

Pendant l’Holocène moyen, le bilan sédimentaire montre de forts contrastes : accrétion importante de l’UF2 entre au moins 7935 et 6220 ans 14C BP, suivie de l’incision I3, rapide, qui a déstocké un très fort volume de matériaux (jusqu’à 15 m d’épaisseur et sur presque toute la largeur de la terrasse T1) entre 6220 et 5300 ans 14C BP. Cette évolution ne peut être expliquée par les variations eustatiques faibles [16,26] ou par des mouvements tectoniques. Le dépôt de l’UF2 paraît lié à un contexte bioclimatique humide et frais [4,8,12,14,38], voisin de ceux du Pléistocène récent, avec production sédimentaire marquée et une hydrologie régulière montrée par les faciès rythmés. Cependant, le faciès supérieur de l’UF2, omniprésent plus tard dans l’UF3, indique des apports plus grossiers et irréguliers, peu en accord avec l’augmentation de l’humidité et de la densité du couvert forestier à cette époque [4,8,10]. Il pourrait traduire une dégradation temporaire locale de la végétation par des activités humaines précoces : la forte densité de foyers anthropiques dans UF2, notée ailleurs au Maroc nord-oriental à cette époque [6], et le début de l’agro-pastoralisme dans le Rif avant 6000 ans 14C BP [3] rendent plausible cette hypothèse. L’incision ultérieure I3 est en accord avec le contexte bioclimatique, devenu très humide et plus chaud dans la seconde partie de l’Holocène moyen [4,8,12,14,38], qui a favorisé le développement de la forêt de chênes et donc la réduction de la production solide.

À l’Holocène supérieur, la forte accrétion de l’UF3 jusqu’au niveau de la terrasse T1 entre 5285 ± 45 et 1370 ± 40 ans 14C BP correspond à une phase de production sédimentaire majeure : en effet, si le flux solide avait été constant, la tectonique et les variations eustatiques ne peuvent expliquer une telle augmentation du stockage dans la basse vallée. Les faciès inférieurs de l’UF3 traduisent bien les environnements humides antérieurs à 4000 ans 14C BP, mais les faciès alluviaux supérieurs et l’abondance des apports colluviaux, parfois riches en cendres, indiquent des apports très abondants, irréguliers, accompagnés d’incendies fréquents. Ceci est en accord avec l’éclaircissement du couvert végétal pouvant résulter de l’aridification et du réchauffement du climat [4,12,17,18]. Mais la désertification végétale peut aussi être due aux activités humaines, dont les effets ont été largement reconnus au Maroc après 5000 ans 14C BP [2,19,28]. Dans la basse vallée du Kert, les nombreux foyers en place dans les sédiments et l’abondance des cendres issues d’incendies sur les versants montrent une forte occupation humaine, surtout entre 4000 et 3000 ans 14C BP. Ces éléments, et le fait que, lors des périodes antérieures, l’aridité induit l’incision, ici comme généralement au Maghreb [1,39,41], conduisent à proposer que l’anthropisation du bassin a pu exacerber l’effet de l’aridité sur la végétation après 4000 ans 14C BP, peut-être aussi modifier l’hydrologie et produire une quantité exceptionnelle de matière ayant engorgé la basse vallée (stocks UF3). L’incision majeure polyphasée apparue après 1370 ans 14C BP (phases I4, I5 et I6), en contexte bioclimatique toujours sub-aride et chaud, semble résulter d’un tarissement des apports solides malgré l’anthropisation croissante liée notamment à la conquête arabe [6,19] : l’exceptionnelle production sédimentaire à l’Holocène supérieur avant 1370 ans 14C BP a pu épuiser l’essentiel de la matière facilement mobilisable sur les versants (sols, régolites) et les aménagements ont pu en stocker une part sur les versants. Les phases de dépôt UF4, UF5 et UF6 sont secondaires : UF4 (terrasse T2) paraît correspondre à un bref épisode de stationnement de l’oued au cours de l’incision ; UF5 (terrasse T3) et UF6 (dépôts actuels) marquent une forte augmentation à la fois de l’énergie de l’oued et des apports depuis les reliefs d’amont, qui pourraient traduire des fluctuations mineures du climat et/ou de l’impact des sociétés humaines.

1 Introduction

A considerable amount of information on palaeoenvironments can be obtained from fluvial sediment composition and distribution in valleys. In Mediterranean regions, fluvial systems are highly reactive to changes in environmental parameters: not only tectonics, which was often active during the Quaternary period [22,42], but also climate change, and of course human activity, which goes back to the earliest times in these regions [7,23].

In the Maghreb generally, the occurrence of Late Pleistocene deposits is rare, while several Holocene fluvial sedimentary units have been observed. Deposition periods were separated by incision periods in which terraces were formed with increasingly lower surfaces than the main terrace, which was formed of deposits during either the Late Pleistocene [1,30,41], or more often the Lower or Middle Holocene [6,37,39,40], Late Pleistocene deposits being generally eroded during the erosion-dominated Holocene period. Holocene sediments sometimes form a series containing palaeosoils, indicating periods of morphological stability [15].

Periods of river erosion or sedimentation are generally related to bioclimatic conditions: according to some authors, sedimentary accretion corresponds to periods of either aridity [15,21], humidity [1,41], or aridity–humidity transition [40]. Human impact on river activity has only be observed for the last two or three millennia [1,7,40]: this impact was high when it was developed in synergy with bioclimatic conditions that were particularly favourable to erosion [7,13], or low when it was antagonistic to climate effects [15].

Lithological and morphological studies of the lower Kert River in northeastern Morocco and 16 14C dating measurements show alternating periods of depth incision and depth sediment accretion during the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene. This paper deals with these sedimentological and morphological data and interpretations.

2 Kert River catchment

The Kert River flows into the Mediterranean Sea 25 km west of the city of Nador (35°11′N and 2°56′W) in northeastern Morocco (Fig. 1). Its catchment (2873 km2) comprises mountains (elevation up to 1800 m in the Rif) made up of a complex mosaic of Palaeozoic to Miocene micaschists, schists, sandstones, marls and limestones, and Miocene and Quaternary volcanic rocks, separated by broad depressions filled with Mio-Plio-Quaternary sediments. This area is marked by an intense seismic activity [9]. The present-day climate is semi-arid Mediterranean (mean annual precipitation 290 mm, mean temperature 17.5 °C), with irregular rainfall. Vegetation is very scarce: forest covers 4% of the catchment surface in the highlands, and elsewhere degraded forest (matorral) or Alfa and Artemisia steppe-like vegetation due to over-pasturing predominates [36].

This study concerns the final 30-km stretch of the Kert River before it reaches the Mediterranean Sea; the elevation decreases from 150 to 0 m, and the mean water discharge is 4 m3 s−1 (but can be as high as 216 m3 s−1). The valley is sinuous and formed by faults (Fig. 1). Several Quaternary alluvial terraces have been described [5,6]. The main terrace, which is omnipresent and up to 1200 m wide, lies about 20 m above the present Kert channel in stretches I and II and has been dated from the Holocene by Barathon [5] and Barathon et al. [6]. Recent alluvium erosion has generated extended sections, up to 10 m thick, and sometimes uninterrupted for several kilometres on both sides of the river.

3 Composition, age and distribution of sedimentary units

Six alluvial units, named UF1 to UF6 from the earliest to the youngest, characterized by 18 lithological facies, and three colluvial units (UC1 to UC3), have been identified along the final 30 km of the Kert (Fig. 2). These units form three alluvial terraces: T1 is the main terrace, 20 m above the present Kert channel in the upstream stretches and 0 m in the downstream stretch; T2 and T3 terraces are lower. 14C dating measurements, expressed according to conventional ages (14C a BP), range from 28,375 ± 450 to 1370 ± 40 14C a BP (Table 1).

14C data. (1) Calibration according to [29,34,35].

Dates 14 C. (1) Calibration d’après [29,34,35]

| Unit | Section | Material | Reference | 14C-age BP | δ13C (‰) | 2σ calibrated 14C-age BP (1) |

| UF3 | A | charcoal | Gif-12086 | 3410 ± 55 | −23.01 | 3486–3831 |

| B | charcoal | Gif-12082 | 1370 ± 40 | −22.58 | 1183–1351 | |

| B | charcoal | Gif-12083 | 2875 ± 65 | −22.48 | 2845–3216 | |

| B | charcoal | Gif-11958 | 3550 ± 40 | −23.12 | 3723–3951 | |

| B | charcoal | Gif-12085 | 3930 ± 60 | −21.66 | 4158–4524 | |

| D | charcoal | Gif-11755 | 3320 ± 55 | −25.03 | 3408–3689 | |

| F | charcoal | Gif-11960 | 3670 ± 65 | −22.38 | 3885–4228 | |

| G | charcoal | Gif-11952 | 3300 ± 50 | −20.24 | 3472–3806 | |

| J | wood | Gif-11954 | 5285 ± 45 | −25.94 | 5933–6175 | |

| K | charcoal | Gif-12087 | 3045 ± 80 | −24.06 | 3001–3440 | |

| L | charcoal | Ly-1197 | 3370 ± 55 | 3465–3819 | ||

| UF2 | B | charcoal | Gif-12088 | 6220 ± 70 | −24.44 | 6941–7274 |

| D | charcoal | Gif-11753 | 7935 ± 45 | −23.30 | 8611–8989 | |

| E | wood | Gif-12084 | 7900 ± 75 | −24.96 | 8559–8992 | |

| UF1 | D | charcoal | Gif-12089 | 12300 ± 155 | −24.6 | 13848–14900 |

| D | wood | Gif-11754 | 28375 ± 450 | −27.57 | #30000 |

Unit UF1 (up to 20 m thick) is widespread in river stretches I, II and III (Figs. 2 and 3). It extends from the present river level up to the surface of T1, and comprises two sub-units, UF1a and UF1b, composed from base to top of the following bodies:

- - unit UF1a (up to 12 m thick): blackish clayey silts containing woody fragment dated 28,375 ± 450 14C a BP, conglomerate, alternating beds of in situ travertine and sand formed of travertine clasts, thick series (3 to 8 m) of rhythmic yellowish sandy beds and greyish silty beds, pebbles in a sandy matrix, pinkish silts with pebbles, yellowish sands with pebbles and greyish silts. Syn-sedimentary faults with normal shift and a throw of several decimetres have been observed in some bodies (blackish clayey silts, travertine and yellowish sands with pebbles);

- - unit UF1b (up to 10 m thick): conglomerates, yellowish sands with pebbles and calcretes, thick series (up to 6 m) of rhythmic pinkish sandy beds and greyish silty beds containing one firesite located two metres under the T1 surface, with pieces of charcoal dated 12,300 ± 155 14C a BP; there is a deep, reddish-coloured soil at the top of UF1, which is either buried (palaeosoil) or crops out.

Upstream–downstream distribution of lithological units. UF1 to UF5: alluvial units; UC1 to UC3: colluvial units; T1 to T3: alluvial terraces.

Distribution longitudinale des unités lithologiques. UF1 à UF5 : unités alluviales ; UC1 à UC3 : unités colluviales ; T1 à T3 : terrasses alluviales.

Both UF1a and UF1b can be observed in the middle stretch of the valley (section D, Fig. 2). In the upstream stretch, only UF1a occurs below UF3 (sections A, B and C, Fig. 2), whereas downstream, only UF1b is observed below UF3 (sections H and I, Fig. 2).

UF2 (up to 10 m thick) was observed in stretches I and II (sections B, D and E, Fig. 2), overlying eroded UF1 deposits; its base lies at the present river level and its eroded top does not form a terrace. UF2 is composed, from base to top, of pebbles in a sandy matrix, series of rhythmic yellowish sandy beds and greyish silty beds, and unrhythmic beds of beige silts and sands. Three dates obtained in this unit range from 7935 ± 45 to 6220 ± 70 14C a BP.

UF3 (up to 20 m thick) was observed in the four defined valley stretches (Figs. 2 and 3). Its base either crops out at the present river level, or lies on UF1 or UF2, and its top often forms the T1 terrace, at a level similar to that of the UF1 top in stretches I and II. It generally comprises, from base to top: darkish organic silts (sections I and J, Fig. 2) or pebbles in a sandy matrix, a main body of unrhythmic beige silty and sandy beds, and series of rhythmic pinkish sandy and greyish silty beds. This last facies shows syn-sedimentary deformations, interpreted as seismite structures [25,33]. The beige silty sandy facies contains widespread layers of greyish silts, enriched with wood ash. UF3 also contains sandy silty colluvium or mud flow deposits close to the valley sides, and, locally, sands formed of travertine clasts. Numerous anthropogenic firesites have been given 11 dates ranging from 5285 ± 45 to 1370 ± 40 14C a BP, most of them between 4000 and 3000 14C a BP (Table 1).

UF4 is not very extensive, and 2 m thick at the most. It overlies eroded UF3 deposits and forms the T2 terrace 12–14 m above the river (sections A, D and H, Fig. 2). UF4, which has not been dated, is composed of beige silty sandy beds, containing pebbles of clayey silty material, overlain by sands made up of travertine clasts.

UF5 makes up the T3 terrace, very marked in the landscape 5 m above the river (sections E, F and H, Figs. 2 and 3). UF5 deposits, 4 m thick at the most, overlie eroded UF1, UF2 or UF3 deposits. They comprise alternations of pebbles with sandy matrix beds and beige silt and sand beds, with predominant cross-bedding. UF5 could not be dated.

UF6 corresponds to the present-day Kert deposits, composed of sands, gravels and pebbles, sometimes with metric clasts, deposited in a braided fluvial channel system. This unit can be several metres thick, but bed-rock sometimes crops out at the river bed bottom.

UC1, UC2 and UC3 colluvial units, interbedded between alluvial units, are 1 to 3 m thick and made up of unbedded sandy silts containing scattered gravels and pebbles. They have not been dated. UC1, reddish in colour, overlies UF1 (sections A, C and I, Figs. 2 and 3) and shows a greyish palaeosoil containing calcareous concretions. Locally (stretch III), a deep torrential unit (up to 10 m thick), made up of blocks and pebbles, fills a gully cut into T1 terrace down to the present river level (section I, Fig. 2). UC2, greyish and with poorly developed palaeosoil, overlies UF2 and is overlain by UF3 (sections B and E, Fig. 2). UC3 overlies UF3 close to the valley sides (sections B, D, E and F, Fig. 2).

4 Interpretation

4.1 Chronology and intensity of incision and sedimentary accretion events

The Late Pleistocene from about 30,000 years was mainly marked by sedimentary accretion. After a period of incision (indexed I0, Fig. 4) down to the present river level, UF1 sedimentary accretion (up to 20 m thick in stretch II) began a little before 28,375 ± 450 14C a BP and stopped soon after 12,300 ± 155 14C a BP on section D, with probably a period of stability or weak incision (I1), not dated, between UF1a and UF1b, as shown by conglomerates filling the channel cut into underlying sediments and yellowish sands with pebbles and calcretes. The dating of 28,375 14C a BP obtained in blackish clayey silts confirms the date obtained by [6] (32,138 ± 1334 14C a BP), but considered as inaccurate by these authors. In stretch II, UF1 makes up the T1 terrace pro parte (Fig. 3). The upper sub-unit UF1b is eroded in stretch I, but crops out widely downstream (stretch III): its top forms a planar palaeosurface with a palaeosoil, preserved over a long distance, whose height above the present river decreases sharply downstream. The UF1 palaeosurface is about 30–35 m under the present shoreline.

Pattern of incision and sedimentary accretion stages in valley stretches I and II. I1 to I6: incision; UF1 to UF6: accretion; T1 to T3: alluvial terraces.

Schéma de l’enchaînement des phases d’incision et d’accrétion sédimentaire dans les secteurs I et II. I1 à I6 : incision ; UF1 à UF6 : accrétion ; T1 à T3 : terrasses alluviales.

The Holocene is marked by alternations of several periods of strong incision and sedimentary accretion (Fig. 4). The major incision I2, shown by an elevation of the UF2 base and UC1 colluvium on UF1, was initiated at the end of the Pleistocene (after 12,300 14C a BP) and/or during the Lower Holocene (before 7935 ± 45 14C a BP): the incision is 20 m deep in stretches I and II. Later, UF2 accretion (up to 10 m) developed during the first part of the Middle Holocene, between at least 7935 ± 45 and 6220 ± 70 14C a BP. These deposits overlie eroded UF1 and do not form a terrace: deep erosion of upper UF2 sediments suggests that top-unit elevation was close to the T1 surface. The next I3 incision period developed during the second part of the Middle Holocene after 6220 ± 70 and before 5285 ± 45 14C a BP. Incision was very extensive, 10–15 m deep and very wide, mainly in valley stretches III and IV. UF3, deposited during the Upper Holocene between 5285 ± 45 and 1370 ± 40 14C a BP, is the most voluminous: deposits up to 19 m thick form the main part of T1. In stretch II, the height of the top of UF3 is similar to that of UF1, which gives the polygenic characteristic of the T1 terrace (Fig. 4). Elsewhere, UF3 covers UF1 or UF2, especially the palaeosoil of UF1b in stretch III. T1 elevation, 20 m above the present river in stretches I and II, decreases downstream to the present-day sea level. The Upper Holocene, since 1370 14C a BP, is mainly marked by incision (20 m upstream and 0 m downstream): three stages of incision (I4, I5 and I6) separated by stages of low sedimentary accretion (UF4, UF5 and UF6) induced lower T2 and T3 terraces.

This pattern of valley evolution differs from that of [6], mainly because these authors did not identify Pleistocene deposits. Moreover, while several morphosedimentary Holocene stages have been identified in Morocco, they are generally fewer and of lower intensity than in the Kert valley [21,37,39,40].

4.2 Origin of sediment budget changes during the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene

In the lower Kert valley, while the final Pleistocene sediment budget is mainly marked by accretion, the Holocene is marked by strong sediment-budget changes. The budget, either positive or negative, is the result of a solid sediment yield value in the catchment and the sediment-retention capacity of the lower Kert valley, which depended on environmental changes during the Holocene, such as tectonics, climate, vegetation, sea level and human activities [24].

UF1 accretion during the Late Pleistocene after 30,000 years BP developed during periods of low sea level, as shown by the sediment palaeosurface elevation, with no obvious major change in river activity. During that glacial period, the fact that deposition predominated for about 20,000 years while the sea level was very low [16,27], as already observed in Morocco [39,41], shows that: (1) sediment yield was high, possibly encouraged by continuous grass-dominated vegetation due to a mainly cool evolution cannot be explained by low sea level did not decrease sediment-storage capacity in the lower valley; sediment storage was possibly encouraged by local subsidence (particularly in stretches I and II), as suggested by [5]. Sediment facies indicate two periods of regular hydrology and a more humid climate: blackish clayey silts, travertine, sands formed of travertine clasts, and rhythmic yellowish sandy and greyish silty beds in the lower part of UF1a, and rhythmic pinkish sandy and greyish silty beds in the upper part of UF1b. This climatic trend is confirmed by pollen data in blackish clayey silts [6]. These periods are separated by facies showing more irregular flows (pebbles in a sandy matrix, pinkish silts with pebbles, yellowish sands with pebbles and greyish silts in UF1a, and conglomerates and yellowish sands with pebbles and calcretes in UF1b), sometimes of high energy, which could have eroded earlier deposits (stage I1 with little incision), with long periods without sedimentation marked by calcrete formation. This hydrological pattern is in accordance with climate changes – more humid at about 30,000 years BP, more arid after 20,000 14C a BP, increased humidity at about 14,000 14C a BP – shown by lake level [17], vegetation [8,20], atmospheric circulation [31,32] and fluvial sedimentation [1] in Mediterranean regions.

Main incision stage I2, developed after 12,300 14C a BP and before 7935 14C a BP during a period of rising sea level [11,27], has frequently been described in Morocco [5,30,37,38,41]. It corresponds to an arid climate period at the end of the Pleistocene and during the Lower Holocene [4,8,20,31], becoming warmer after 10,000 14C a BP [12]. As steppe vegetation was favourable to sediment yield at that time, only irregular and sometimes high-energy river flows can explain how solid matter was carried down to the sea and deep incisions in UF1 sediments developed.

During the Middle Holocene from 8500 14C a BP, climate humidity first increased while the temperature decreased, then from 6500 to 4000 14C a BP humidity continued to rise and the temperature also increased: this has been referred to as the ‘climatic optimum’. After that, aridity developed up to the present day [4,8,12,14,38]. During this period, the sediment budget varied greatly: high sediment accretion developed from at least 7935 to 6220 14C a BP, then I3 incision occurred rapidly between 6220 and 5300 14C a BP, reworking a vast volume of material (15 m high for a large part of T1 extension). This contrasted evolution cannot be explained either by sea level variation, which was low during the Middle Holocene [16,26], or by tectonics. UF2 deposition seems to be related to a humid and cool climate, similar to the Late Pleistocene, which could have induced significant sediment yield and regular hydrology, as shown by rhythmic yellowish sandy beds and greyish silty beds observed in both UF2 and UF1. Nevertheless, upper UF2 facies of unrhythmic beige silty and sandy beds, which are more predominant in UF3, show discharges of coarser material as a consequence of irregular hydrology, which is inconsistent with increased humidity and forest cover at that time [4,8,10]. This type of facies could indicate temporary clearing of vegetation in the catchment due to either climate change (weak aridification?) or early human activities. This hypothesis is supported by an abundance of anthropogenic firesites in UF2, found extensively elsewhere in northeastern Morocco at that time [6], and the beginning of crop cultivation and pasturing in the Rif Mountains from as early as 6000 14C a BP [3]. A further I3 incision stage is consistent with a warmer and very humid climate during the second part of the Middle Holocene, which favoured oak-forest development and thus decreased sediment yield.

During the Upper Holocene, from about 4000 14C a BP, the climate was marked by high aridification [4,17,18] and was warmer [12]. Strong UF3 accretion up to the T1 level between 5285 ± 45 and 1370 ± 40 14C a BP corresponds to periods of major sediment-yield increase, because this increased sediment storage in the lower Kert valley cannot be explained by tectonics or sea-level change. Lower UF3 facies (darkish organic silts and travertines) are consistent with a humid climate prior to 4000 14C a BP, but the widespread development of further unrhythmic beige silty and sandy beds, sometimes rich in wood ash and with abundant interbedded colluvial deposits, indicates the discharge of large quantities of solid material from the valley sides, fostered by irregular hydrology and frequent vegetation fires. Increased slope erosion and sediment yield, related to less protection of the soil by vegetation, could be due to a more arid climate. Desertification could also be due to vegetation clearance by human action, often seen in Morocco since about 5000 14C a BP [2,19,28]. Abundant in situ firesites and dispersed wood ash in UF3 sediments indicate extensive human activities in the lower Kert valley, especially between 4000 and 3000 14C a BP. Previous arid periods are characterized by incision in the river stretches studied, as it is frequently the case in the Maghreb [1,39,41]. From these observations, it can be concluded that human activities added to aridity affect vegetation, and probably also hydrology, after 4000 14C a BP. These environmental changes probably induced such a high sediment yield in the catchment that the Kert River could not discharge its whole sediment load downstream to the sea, storing a great part of it as UF3 deposits. Major cumulated incision developed in three stages (I4, I5 and I6) after 1370 14C a BP, without significant change in the warm, arid climate, which seems to indicate a sharp decrease in sediment yield, while human activities increased, particularly following the Arabian migration [6,9]. It is possible that a very high sediment yield during the Upper Holocene before 1370 14C a BP used up the source of material suitable for erosion (soils, regolites), or that eroded material was partly stored on slopes due to human activities. During this incision-dominated period, UF4, UF5 and UF6 deposition stages are slightly marked. UF4 sediments forming sparse T2 terrace seem to have been deposited during a brief period without incision. UF5 deposits, forming T3, and UF6 deposits show a high increase in river-water energy (predominance of sands, gravels and pebbles); they are mainly composed of coarse material discharged from upstream mountains, possibly indicating slight changes of climate or human action.

5 Conclusion

While the Late Pleistocene after 30,000 yrs BP, mainly cool and humid, but sometimes more arid, is mainly marked in the lower Kert valley by sedimentary accretion (UF1) forming part of the major T1 terrace, the Holocene period is marked by the alternation of three incision stages (I2, I3 and I4) and two accretion stages (UF2, UF3) with roughly similar height ranges, between the present-day river level and the polygenic surface of the T1 terrace. During the Lower and Middle Holocene, this highly contrasted morphosedimentary evolution seems to be due to bioclimatic trends that did not appear during the Late Pleistocene: UF2 sedimentary accretion at the beginning of the Middle Holocene seems to have been induced by climate cooling and humidity similar to that of the normal Late Pleistocene environment, while I2 and I3 incision stages correspond to a warmer climate, respectively extremely arid and extremely humid. During the Upper Holocene, the continuously warm and arid climate did not have the same effect on the fluvial sedimentary system as before, due to the emergence of more contrasted morphosedimentary Holocene events: UF3 accretion and I4 to I6 incisions. Human activities and changing earth surface conditions seem to have induced new responses of the fluvial geosystem to climate characteristics.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by the ‘Action intégrée de coopération franco-marocaine’ AI MA 01/01 (‘Érosion des sols et sédimentation dans les milieux aquatiques continentaux’) between the Science and Technology Faculties of Tours (France) and Fès (Morocco). We thank the French and Moroccan authorities for their help. We thank Elisabeth Yates for her assistance in translating this text and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.