1 Yemen as a key place for regional prehistoric research

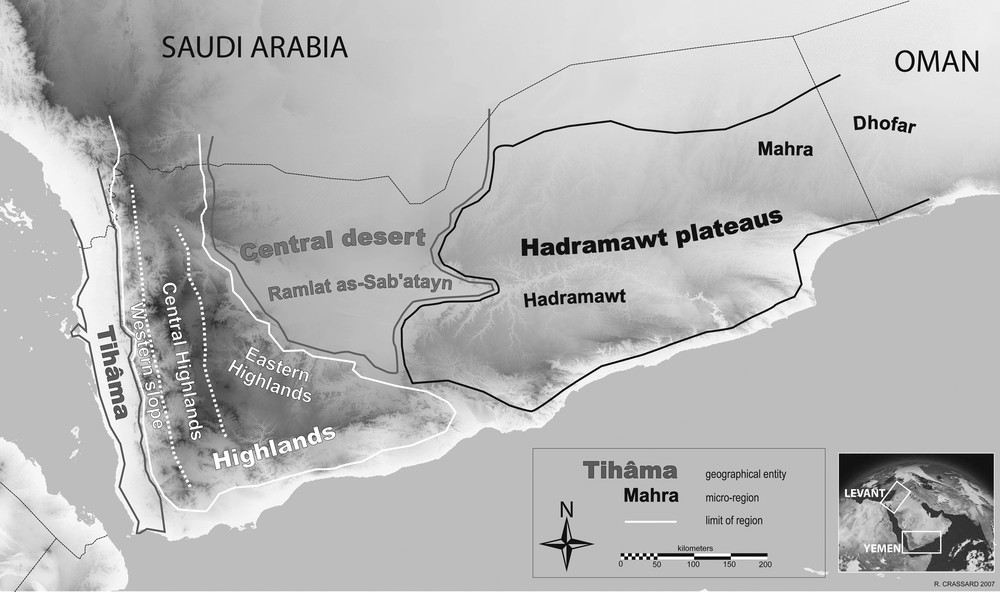

From the Pleistocene to the Early and Mid-Holocene, Southwest Arabia (Fig. 1) is considered a potential crossing point between Africa, the Levant and the rest of Asia. Its strategic geographic position prompts debates on topics as varied as the exit of Africa by the first hominids and modern humans [3,5,31,40,47], the diffusion of the Levallois concept during the Middle Palaeolithic [25,30,33,48,51], and the networks of influence between the Neolithic cradles and their peripheries [2,18,27,37].

Geographical entities in Yemen.

Fig. 1. Entités géographiques du Yémen.

Currently palaeoenvironmental and more specifically palaeoclimatic data refine our knowledge of prehistoric occupations. Wet phases set within a context nowadays dominated by aridity suggests favourable periods for the settlement of prehistoric societies during the Pleistocene [6,44,45,52,59]. During the Holocene, humidity reached its maximum [53] during the Arabian Humid Period [38,42] (7500–5500 BC Cal). This period is highlighted by the evolution of the monsoons described by analyses of palaeosols, palaeolakes or speleothems [15,32,41,42,49,50,53,54].

When compared to Europe and the Levant, prehistoric research in Yemen is a recent phenomenon. Until recently, archaeological research simply dealt with general questions of prehistoric occupation in Yemen, even though old settlements were very quickly recognized [1,7,36,56]. Consequently, some people regard southern Arabia as a cul-de-sac, not only geographically, but also culturally [22,34]. The recent focus on this area is generating a refined chronocultural framework and demonstrating a much less negative image.

2 Surface and stratified sites in Yemen

For several decades, Yemen has been revealing a significant number of lithic industries, datable to the Pleistocene and the Holocene. In some cases, their origins are known with precision, and in others, completely ignored or poorly understood. These industries almost always come from surface sites, as climatic and erosional processes cause a partial or total destruction of sediment cover. Heavy objects, including a large number of knapped stone, remain in place after loose material is scoured away. Thus, while deflation sometimes allows easy site discovery, it also leads to the destruction of the archaeological context. Dating, whether it is absolute (chronometric) or relative is then made difficult.

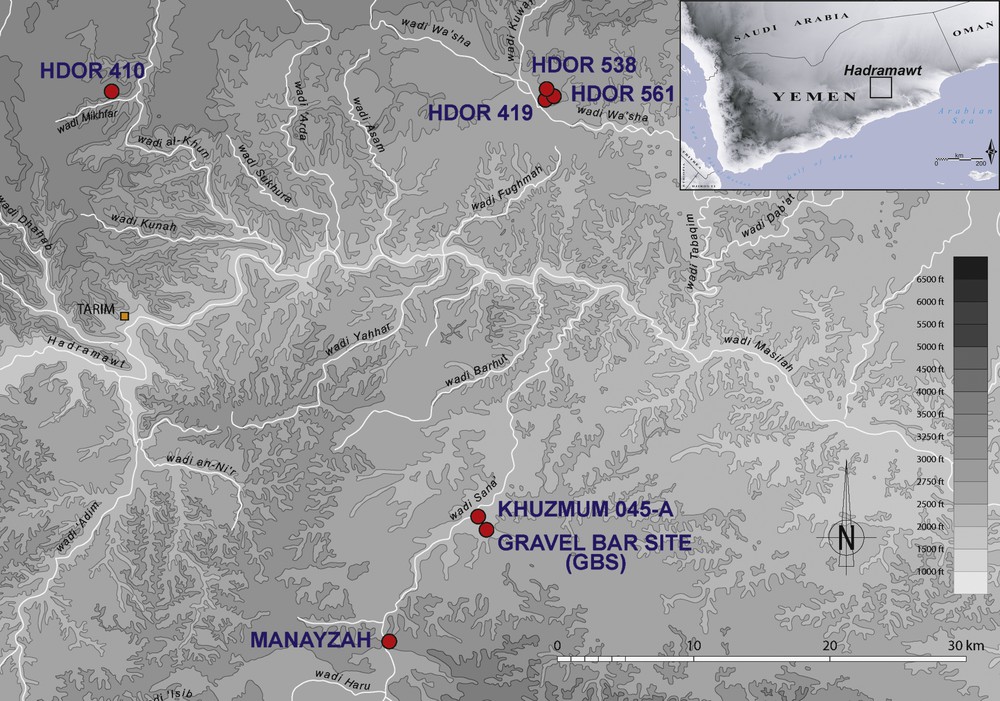

In recent years, the discovery of Holocene sites with preserved sedimentary accumulation has more than doubled the information of known, prehistoric stratigraphies in Yemen. These sites, such as Manayzah [28], HDOR 410 and HDOR 419 [26,29], Khuzmum [23,46] and GBS [23,57], are all located in the Hadramawt of eastern Yemen (Fig. 2). This geographical entity proves to be a particularly favourable area to improve our understanding of old and recent prehistory, as many sites from various periods have been identified there during intensive, systematic surveys [23].

Stratified sites in central Hadramawt.

Fig. 2. Sites stratifiés du Hadramawt central.

3 The local peculiarities of lithic technology in Early/Mid-Holocene South Arabia and its comparison with the Levant

3.1 Stratified and surface sites joined together by the study of lithic industries

Because of the use of pressure retouch in shaping arrowheads, an intellectual shortcut led archaeologists to regularly associate the presence of these tools in South Arabia with the prepottery Neolithic in the Near and Middle-East (including the ‘Fertile Crescent’). The contribution of recent data leads us to modify the situation in Yemen. The discovery of techniques specific to the Yemeni territory during the Holocene suggests that local populations were not in direct contact with contemporary human groups of the Levantine regions. From the 8th to the 5th millennium BC, typical techniques from Yemen include the use of fluting, now well-known but considered for a long time as exclusively present in the Palaeoindian societies of the American continent during the extreme end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene [16,28].

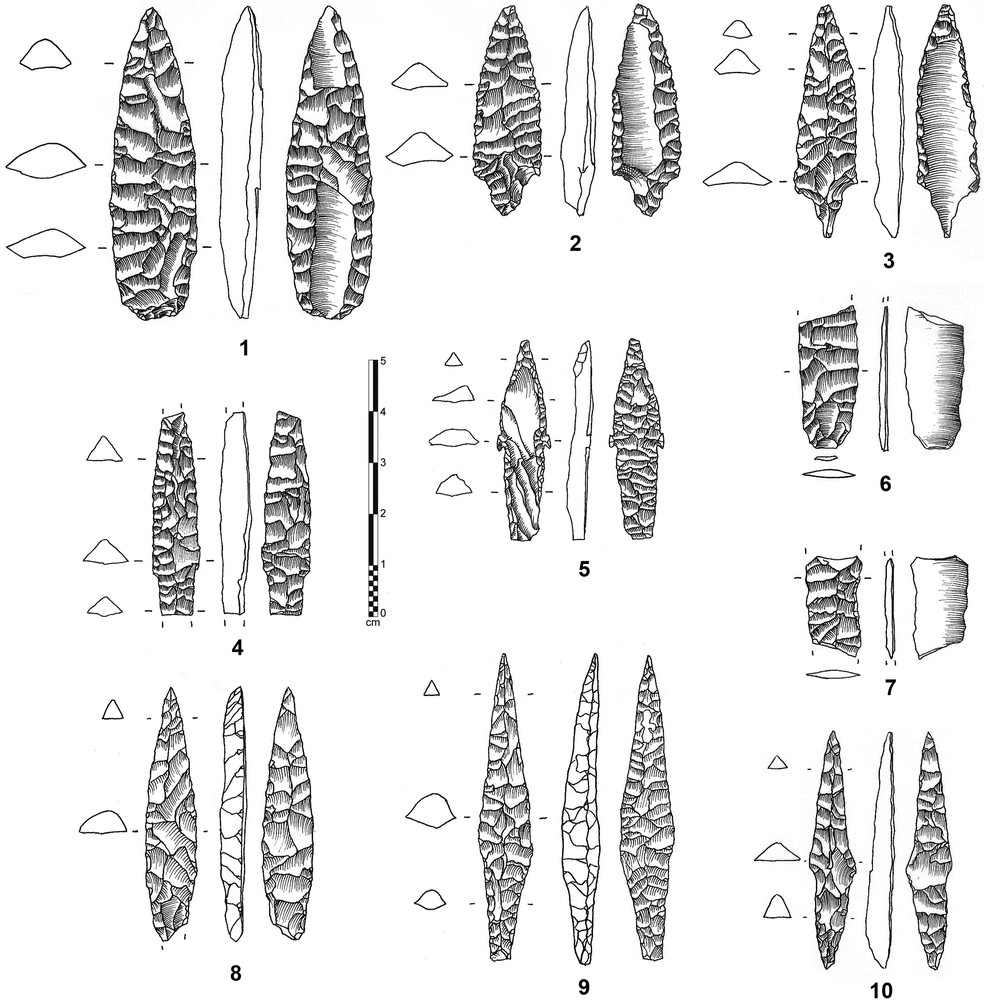

Fluting (Fig. 3:1-3) is, for instance, very well illustrated at the site of Manayzah in Wadi Sanâ [28]. This Early to Mid-Holocene site is exceptional for its deep and well-preserved occupational stratigraphy. Here, an unparalleled corpus of stone tools, animal bone, and clearly defined activity and dwelling areas, as well as elements of stone and shell jewellery are found. Lithic industries are widely diversified with worked obsidian, bifacial arrowheads, and numerous other tool types. The fluting technique appears in stratigraphy and is now dated to the first half of the 6th millennium BC by radiocarbon assay on associated organic material (Table 1; for a complete inventory of radiocarbon dates from Yemen see [23], pp. 46–48). The technique involves extracting a flake longitudinally along the axis of the piece from one of its extremities, mainly from the point in Arabia [16]. The characteristic waste of this production (“channel-flakes”, Fig. 3:6,7) were found on the site itself in Manayzah, proving that this technique was implemented by the occupants of the site. Manayzah is also exceptional since it is a rare example of a stratified site delivering faunal remains in great quantity. Fauna are present in most of the layers excavated to date. According to initial results, it seems that the first indices of animal domestication may appear in the 6th millennium BC [43].

Lithic industry from Manayzah: 1–3: fluted points; 4,5: trihedral points; 6,7: channel-flakes. Trihedral points from Hadramawt: 8: HDOR 410; 9 HDOR 419; 10 Khuzmum 045-A (drawings J. Espagne).

Fig. 3. Industrie lithique de Manayzah : 1–3 : pointes flûtes ; 4,5 : pointes triédriques ; 6,7 : chutes de flûtage. Pointes triédriques du Hadramawt : 8 : HDOR 410 ; 9: HDOR 419 ; 10 : Khuzmum 045-A (dessins J. Espagne).

Dating of the various layers.

Tableau 1 Datation des couches.

| Site/Layer | Nature | Laboratory reference | 14C age BP | 1σ calibrated age BC | Bibliographic reference |

| HDOR 410 (A5 Niv 3 Fy 7) | Charcoal | AA64365 | 6030 ± 56 | 4993–4848 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 410 (Niv 4 prox Fy 12) | Charcoal | AA64369 | 6389 ± 58 | 5466–5318 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 410 (B5 Niv 4 Fy 12) | Charcoal | AA64368 | 6651 ± 50 | 5625–5544 | Crassard [23] |

| Manayzah (K9-Hearth1) | Charcoal | AA59570 | 6902 ± 41 | 5835–5733 | Crassard et al. [28] |

| HDOR 419 (A13 Niv 5 b) | Charcoal | AA64360 | 6931 ± 48 | 5872–5743 | Crassard [23] |

| Manayzah (l14 C 009-10) | Charcoal | AA66684 | 6981 ± 51 | 5973–5802 | Crassard [23] |

| Manayzah (L9 A 010-15) | Charcoal | AA66683 | 6987 ± 57 | 5976–5807 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 419 (A12 Niv 3 a) | Charcoal | AA64358 | 7016 ± 52 | 5981–5845 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 419 (A13 Niv 5 a) | Charcoal | AA64359 | 7017 ± 52 | 5982–5845 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 419 (A12 Niv 4 a) | Charcoal | AA64355 | 7022 ± 52 | 5983–5847 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 419 (A13 Niv 5 d) | Charcoal | AA64362 | 7042 ± 53 | 5990–5844 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 419 (A14 Niv 5) | Charcoal | AA64364 | 7086 ± 50 | 6016–5910 | Crassard [23] |

| Manayzah (K9-017) | Charcoal | AA66685 | 7133 ± 51 | 6057–5933 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 419 (A13 Niv 5 e) | Charcoal | AA64363 | 7169 ± 52 | 6071–5995 | Crassard [23] |

| HDOR 419 (A13 Niv 5 c) | Charcoal | AA64361 | 7270 ± 120 | 6242–6014 | Crassard [23] |

| Khuzmum Rockshelters, hearth 2000-045-1A-004 | Charcoal | AA38543 | 7403 ± 70 | 6378–6223 | McCorriston et al. [46] |

| Khuzmum Rockshelters, hearth 2000-045-1A-009 | Charcoal | AA38548 | 7723 ± 87 | 6633–6476 | McCorriston et al. [46] |

| Manayzah (K9-020) | Charcoal | AA66686 | 8072 ± 79 | 7174–6830 | Crassard [23] |

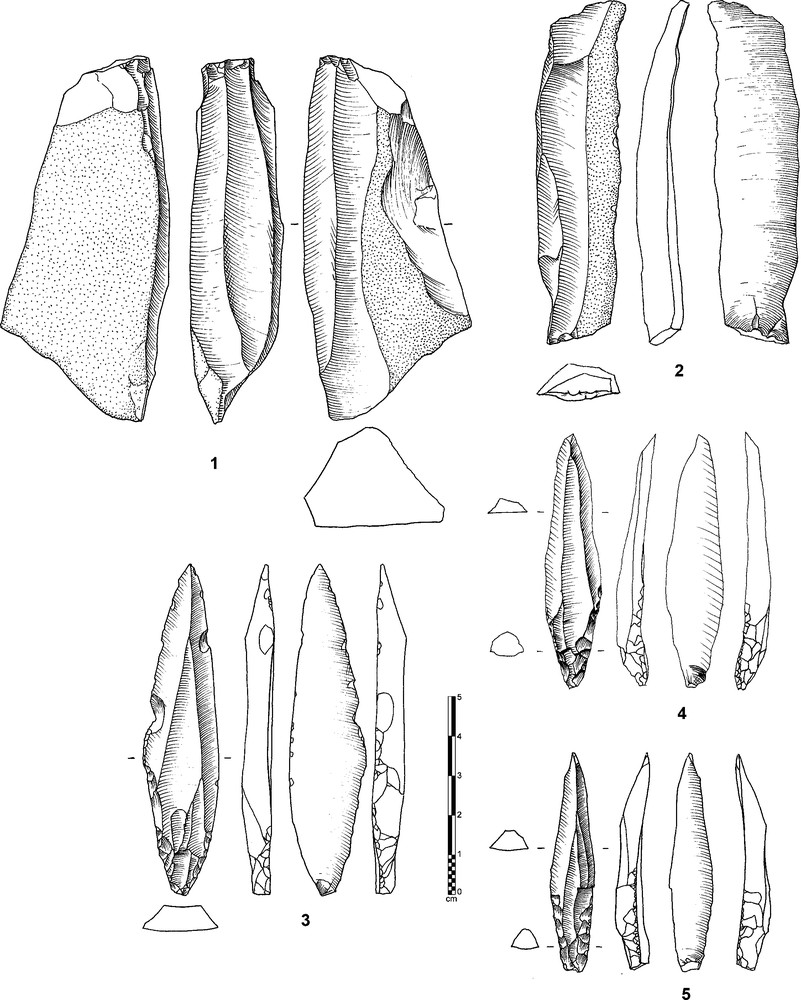

In addition, several technical schemes and modes of lithic production, unknown or little documented until now, were discerned in the Hadramawt region. The description of the Wa'shah debitage method [24,26], which is only present on the surface of Wadi Wa'shah and Wadi Sanâ plateaus, marks an important stage in the definition of a chronocultural framework for South Arabian prehistory (Fig. 4). The existence of this predetermined mode of pointed blade production affirms with certainty the presence of prehistoric populations using a laminar technology. This method, while being very close to the Levallois debitage concept, takes place only on laminar volumetric structures, and not from a flat surface. Its precise dating is still unknown even though some laminar indices are found in stratigraphy, in particular at HDOR 419 [29]. At this point, only a vague date can be proposed, since no datable material has been found, ranging from the very end of the Pleistocene to the Early Holocene.

Wa'shah debitage from Wadi Wa'shah, Hadramawt: 1. core; 2. lateral semi-cortical blade; 3–5: Wa'shah points (drawings J. Espagne & R. Crassard).

Fig. 4. Débitage Wa'shah du Wadi Wa'shah dans le Hadramawt : 1. nucleus ; 2. lame semi-corticale latérale ; 3–5: pointes de Wa'shah (dessins J. Espagne & R. Crassard).

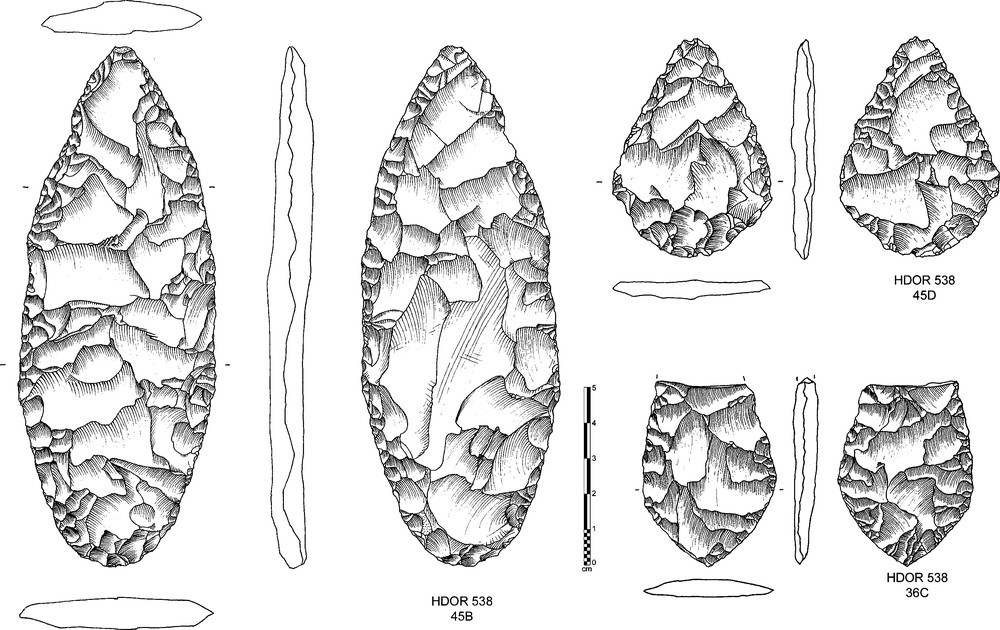

Finally, the bifacial shaping of foliate pieces in Wadi Wa'shah (Fig. 5) also indicates elaborate knowledge of knapping, foliate pieces being a rather rare phenomenon in Arabia (but well-known on site HDOR 538, [23]). These data would thus suggest the existence of true independent sociocultural complexes in Yemen during the Early/Mid-Holocene.

Foliated bifaces from Wadi Wa'shah, Hadramawt (drawings J. Espagne).

Fig. 5. Bifaces foliacés du Wadi Wa'shah dans le Hadramawt (dessins J. Espagne).

3.2 Arrowheads as a major indicator for refining Holocene chronocultural framework

Arrowheads allow for detailed analyses across the majority of the sites found on the surface and in stratigraphy (for complete typological analyses, see [23], pp. 141–143 and 163–166). Data from stratified Early/Mid-Holocene sites in Hadramawt, now five in number (HDOR 410 in Wadi Mikhfar, HDOR 419 and HDOR 561 in Wadi Wa'shah, Khuzmum 045-1A and Manayzah in Wadi Sanâ), are given precedence. Three typological groups were distinguished: flat bifacial arrowheads with symmetrical section, arrowheads with trihedral section and arrowheads on flakes or blades. The description of these typological groups led to two principal conclusions.

First, the greater antiquity of the flat bifacial arrowhead type is probable when compared to the trihedral-point type. The flat bifacial points include several subtypes which are distinguished chronologically from the trihedral points and probably attest to production by groups of different traditions since these two typological assemblages are never found together in stratigraphy.

Second, the typological group of the trihedral points (Fig. 3:4,5,8–10) seems to belong to only one chronological episode, around the 6th millennium BC. Trihedral industries are thus interpreted as pertaining to one particular chronocultural ‘facies’. The homogeneity of chronometric dates that were obtained from archaeological layers containing trihedral points at four distinct sites confirms this interpretation.

4 Regional peopling and external influences (environment, topography, cultural traditions) during the Early/Mid-Holocene

4.1 Influences from the natural environment: climate and topography

4.1.1 Climate and man: general remarks about Southwest Arabia

In the lowlands, vegetation remained of an arid or semi-arid type during the Arabian Humid Period because of consistently high evaporation rates and the presence of the Yemeni highlands to the west and Hadramawt plateaus to the south/southeast. The broken terrain acted as topographic and ecological barriers to the northward penetration of tropical plants. Moreover, during the Early/Mid-Holocene, the nature of prehistoric occupations of the lowlands seems to be closely related to the availability of water. For example, no human presence can be demonstrated from Ramlat as-Sab’atayn desert apart from during the periods when lakes were formed and stabilized.

Surface sites, like those at al-Hawa, in Ramlat as-Sab’atayn, attest to the presence of nomadic or semi-nomadic communities. Camps built out of stones begin to appear after 6,000 BC in the Arabo-Persian Gulf, whereas permanent sedentary occupations seem to develop from 3,500 BC under climatic conditions of increasing aridification. The adaptive modalities of human groups during this more recent period are centred around complex irrigation systems (falaj in Oman Peninsula and exploitation of the slopes in Southwest Arabia), with food production focused on the exploitation of maritime resources on the coasts and dates and cereals inland [21].

It seems that the climate has played a role in the occupation strategy of prehistoric human groups. It is, however, necessary not to overemphasise its impact on the choices made by human populations, and to consider the adaptability of small groups in arid contexts. It should also be mentioned that a decrease in precipitation does not imply a total lack of water resources [18]. The current Bedouin, who live isolated from the industrialized world, represent the last heirs of a way of life based on seasonal nomadism. Their way of life is disappearing, but this cannot be explained by the extreme aridity or the lack of access to food resources they endure today. It is more for socioeconomic reasons related to our modern world. A good number of Bedouin, particularly in Hadramawt, continue to live a pastoralist way of life based on small livestock (goats, sheep, and camels). They move according to their access to grazing grounds and, because of their low numbers, live under very similar conditions to Early/Mid-Holocene populations although the climate is much drier.

As Cleuziou and Tosi [20] observe, it is fundamental to distinguish between data obtained from sites with a strong anthropogenic signature and those resulting from little or no human influence. Failing this, “one would condemn oneself… to confuse the action of man and global change, always explaining the first by the second”. Climatic variation thus results in a certain number of parameters that guide choices in the occupation of the ground. Climate however is not the exclusive and unavoidable determinant for the development of a way of life. Human adaptability within an environment still constitutes an unforeseeable factor and has been little limited in human evolutionary history.

4.1.2 Ramlat as-Sab’atayn as a “buffer-zone” between the western Highlands and Hadramawt

In this section and the next two examples of key-zones in Yemen are examined. They had very different roles according to their topographic characteristics: the central desert of Ramlat as-Sab’atayn; and the Tihama coastal plain along the Red Sea.

Nowadays, Ramlat as-Sab’atayn is one of the most inhospitable sand deserts on the planet. It is thus surprising to find Early/Mid-Holocene occupation remains there. However, climate studies show that this area was probably a passage zone and a “zone of life”, thanks to the presence of water, materialized by more or less perennial lakes. It was thus a privileged passageway between the western Highlands and Hadramawt. Two valleys doubtlessly contributed to the diffusion of human and cultural currents: the large Wadi Jawf and the mouth of the equally impressive Wadi Hadramawt. Trihedral points are thus found from the Oman Peninsula [12] to the region of Sa’da [37], and along the Jawf-Hadramawt palaeo-river [19], revealing a link between the central desert's bordering areas, at least during the 7th/6th millennia BC.

What role did the landscape play in the diffusion of the technocomplex based on trihedral and bifacial industries and sometimes by the fluting technique? The presence of water in the Ramlat as-Sab’atayn desert during the Early/Mid-Holocene sustained and facilitated the diffusion of human groups, and thus, cultural traditions like knapping techniques and the types and forms of lithic weapons and tools. Access to the Highlands from the east did not seem to be an insurmountable obstacle. Expansion to the Tihama region towards the west was nevertheless much more problematic. The eastern coast of the Red Sea may then be considered as truly isolated from the more easterly lands, and instead turned towards the African coasts.

4.1.3 Tihama: a territory apart

Tihama region is constrained by the escarpment at the western edge of the western Highlands. The few wadis which notch this geographical characteristic could have possibly allowed an opening-up of Tihama during the Early/Mid Holocene for short periods, thus allowing the intrusion of certain lithic industries, but primarily the barrier supported the development of others which were particular to Tihama. As a matter of fact, obsidian and other volcanic rocks were generally used as soon as the Mid-Holocene, a characteristic rather circumscribed within Tihama. From the 2nd millennium BC, Tihama finds a place in trading with easterly regions with a quasi-systematic production of geometric microliths [23].

4.1.4 A topographic structural influence

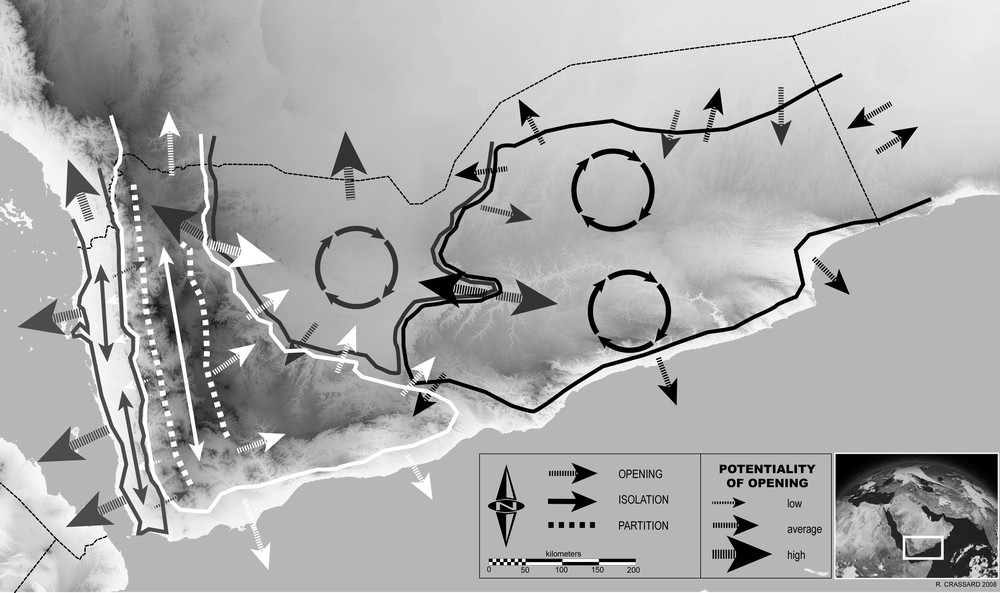

The examples of Tihama as an isolated zone and Ramlat as-Sab’atayn desert as a “buffer-zone” mark the important role played by topography, and the landscape and climate in general, in the diffusion and development of lithic industries and the groups who produced them. Thus potential zones of isolation, connection and separation are distinguished according to these parameters. Fig. 6 shows these zones and the comparative possibilities for the connections of an area, with more or less degree of importance. There are then some major zones of connection such as Wadi Jawf or Wadi Hadramawt, some zones relatively isolated from the inland areas like Tihama and some zones of separation, like the large western escarpment of the western Highlands.

Potential zones of isolation, connection and separation in Yemen during the Early/Mid-Holocene.

Fig. 6. Zones potentielles d’isolation, d’ouverture et de séparation au Yémen pendant l’Holocène ancien/moyen.

4.2 Influences from the cultural environment: the neighboring regions

4.2.1 Influences from the north?

South Arabia, and particularly the Yemeni territory, has long been considered a “satellite area” or “passive margin” under the influence of the Levantine cultures. This consideration is mainly influenced by greater archaeological knowledge advancement in the Levant than the Arabian Peninsula, thanks to a much wider archaeological research investment in the former region in terms of people and time. Nevertheless, explaining the nature and development of South Arabian prehistoric cultures solely from a Levantine perspective is problematic, especially when influenced by prejudicial views of South Arabia as an “elephants cemetery” [34], or a “cul-de-sac” of the Levantine diffusion for the Pleistocene as well as the Holocene [22]. The scarcity or absence of stratified sites in Yemen however acted for a long time in favor of these prejudices.

Chronological terminology suffered from these comparisons, and the Yemeni “Neolithic” appeared in the nomenclature as part of the “logical” periodisation of any prehistoric civilization. On which criteria was this appellation based?

Initially, PrePottery Neolithic societies (PPNA, PPNB and PPNC) from the Levant used the pressure retouch technique in the creation of lithic tools, and particularly in arrowhead manufacture. While having a Neolithic way of life based on a production economy, these populations did not yet know ceramics, or at least did not produce any. This situation was connected rather clearly with the one observed on Yemeni surface sites: pressure shaped arrowheads and absence of pottery. A missing key element was consequently neglected: no proof of any production economy had been clearly discovered in South Arabia. The comparison thus stopped with typological considerations. Moreover, the comparisons with the Levant did not take into consideration the very common laminar component in Levantine assemblages (including naviform cores and pressure debitage), which was quasi-absent in those from Arabia. Also, fluting and trihedral points are not found in the Levant.

Thus, without evidence to the contrary, we cannot detect any particular link in terms of typology, technology, artistic representations, symbolic system, etc. during the Early/Mid-Holocene between the Levant and Southwest Arabia.

4.2.2 Interrelationships with the east?

Comparison with Holocene sites from the eastern regions outside Yemen is definitely more relevant than those with the Levant. In this regard, recent syntheses by Cleuziou [18] and Charpentier [12] reveal close links between certain South Arabian Holocene populations.

Certain truly Neolithic populations are attested within the Sultanate of Oman, in particular at many coastal sites [4,10,11,13–15,21,55]. A comparison of lithic industries attests close links with industries from Yemen.

The presence of industries on flakes and blades, like the Fasad points [9] or the Wa'shah points [24], is an interesting fact underlining a laminar conceptualization in lithic arrowhead production. It is a first common point which may appear at the beginning of the Holocene.

Trihedral points, typical at the beginning of the Mid-Holocene, are found from the Oman Peninsula's eastern regions across to the Yemeni Western Highlands. They ultimately represent a technical and typological link which most probably gave way to the apparently slightly later fluting technique, especially in Yemen and to a lesser extent in Oman and the United Arab Emirates [11,16].

These comparative data reveal technical and typological complexes that lie within a chronocultural framework that is being constantly updated by new stratified sites discoveries. Some real “cultural waves” have thus existed in South Arabia, and without evidence of external origins, these very probably suggest endemic development.

4.2.3 Interactions between Africa and Southwest Arabia beyond the Tihama region?

The archaeology of the East African Holocene is still far from understood. Very strong links are known for recent prehistory (3rd/2nd to 1st millennium BC) on both sides of the Red Sea coasts (obsidian trade, megalithism, rockart [39]). They are on the other hand more difficult to highlight for the older periods. Isolation of the coastal plain of Tihama has been shown for the Early/Mid-Holocene, and few elements therefore allow suggestion of interactions between Africa and the regions located to the east of Tihama. The question of how these two areas were connected thus remains unanswered.

4.2.4 Arabia as a pole of influence?

If Southwest Arabia is really located “at the margins of the large Neolithic cradles” [35], and in particular of the Fertile Crescent, it is probable that this region “took another way” [18]. Yemen ‘Neolithisation’ seems to occur tardily, as in the rest of South Arabia, with a way of life centered around a production economy from the period known as the “Bronze Age” around the second half of the 4th millennium BC.

That does not preclude however the presence of groups of pastoralists/hunter-gatherers dated to the 6th millennium BC, whose first indices, in Manayzah in particular, will be confirmed by the study of the faunal remains [43]. Is it possible at that time to speak about a “specific pole” of influence for Yemen? If this expression seems rather strong, we may prefer to speak of an “endemic development area” that one can particularly detect in South Arabian lithic industries. Those unquestionably reveal common stylistic and technique objectives, which do not find, for the time being, any comparative referent in the neighbouring regions.

5 Territorial occupations and Yemeni particularities during the Early/Mid-Holocene

5.1 Occupation of the Tihama Red Sea coastal plain

The Arabian Humid Period was favourable to settlements close to mangrove environments (for example the site of ash-Shumah [8]). During this period, these milieus could develop and provide important food resources, like molluscs, to populations likely lacking much mobility.

The end of the Humid Period sees a progressive aridification, a slight lowering of the sea level and a partial retreat of typical Early Holocene mangrove habitats. These observations are confirmed by the evolution of river deltas and by coastal site distributions moving inland to the east after the 7th/6th millennia BC. From the 4th millennium BC, sites are close again to coasts and wadi edges, revealed by intensification of fishing activities and by remains of domesticated animals, whereas evidence of a production economy is still visible but to a lesser extent [39].

In parallel, the coastal communities are characterised by use of obsidian originating in Africa from the 6th to the 1st millennium BC. These interrelationships suggest a more or less developed and intensive navigation, and the ichthyofaunal remains attest to high levels of sea-fishing, at least for the most recent times.

5.2 Occupation in the western Highlands

Few data allow the proposal of a preliminary picture of Early Holocene occupation in the Yemeni Highlands. At that time, a certain environmental stability was present, which did not require particular modification of the landscape. Human impact on the environment was thus negligible and few archaeological indices remain from this period, these having gradually been destroyed by the successive and intensive later occupations. Early-Holocene palaeosols in the Highlands show organic stability [58] indicating that environment was sufficiently stable to replenish the natural resources even if some degree of overexploitation existed at that time.

5.3 Occupation in Ramlat as-Sab’atayn central desert

The large central sand desert is the geographical component that has been most dependent on the climate during Yemen's regional human occupation history. With its hyperaridity associated with the difficulty of crossing it, Ramlat as-Sab’atayn is not a preferred place for human settlement. The desert did however play an important role as a probable “buffer-zone” between eastern and western regions. Diffusion of trihedral arrowhead industries is attested there. The presence of lakes, and thus favorable conditions for occupation or crossing, improved human preference for the place during the Arabian Humid Period. Grinding tools were discovered there [38] and are good indicator towards positing a certain perennial habitation of the sites along the lakes’ edges.

5.4 Occupation in Hadramawt plateaus region

The Hadramawt plateaus are the best known area for Yemeni prehistory. It is already possible to propose a model of occupation of the various components of the landscape, according to surveys carried out from wadi beds to plateau tops [26].

Wadi beds are not favorable for conservation of archeological sites. Scouring by floods, often violent in these contexts, causes destruction to the layers. However, the formation of large terraces via silt accumulation could have sealed prehistoric sites. Only the Manayzah site (Wadi Sanâ) is an exception, since it may have been very well preserved thanks to its slightly shifted position relative to the principal wadi course.

Some terraces are located between 20 and 50 m above the wadi beds. They shelter a high density of prehistoric layers, but are very often deflated, delivering Middle Paleolithic to Holocene industries. The lithic raw material is present in the direct vicinity but is often of poor quality. However, excavation at HDOR 410 site [23]) proves that the topographic context of these terraces can sometimes preserve stratigraphic deposits.

Finally, raw material is abundant at the top of the plateaus. Holocene sites are numerous, mainly in the vicinity of lithic raw material. Stratigraphic accumulation could be conserved when sites were in contexts protected from the erosive phenomena, such as for instance HDOR 419 or HDOR 561 [26].

6 Synthesis

Two occupation models can thus be proposed: a diffusionist model seeing a Levantine influence in Arabian lithic industries, and a second model privileging an endemic development of Early/Mid-Holocene hunter-gatherers societies leading to some of the very first elements of a Neolithic way of life, like pastoralism. These two models both have their credibility, perhaps dependent on the period under examination. The diffusionist model is however not attested to by archaeological vestiges and thus remains a purely theoretical one. It represents a search for external influences in the attempt to explain absent elements in Yemen, and represents the “escape” generated by generalization in archaeological science, which inevitably leads to diffusionist conclusions [17].

The description of an alternative model has important theoretical interest, and fits more broadly into global questions about the place of peripheral zones in comparison with the “classical Neolithic centers” of innovation and invention. The research perspectives that the Arabian Peninsula offers are therefore increasingly important in attempting to better comprehend the evolution of hunter-gatherers societies.

Concerning the modalities of occupations throughout the Holocene period, the influence of the climate was important but not inevitably decisive. The humid periods certainly contributed in supporting displacements and relations between various groups. On the other hand, the drier periods do not necessarily have to have impelled human groups to leave the area. They could have found refuge zones like mountains and high plateaus, or they might have decreased the number of individuals within the group, in order to better profit from food access. Trading could also have been intensified during these periods, between groups which had difficulty accessing resources and those more capable of providing for their own needs.

Holocene occupations were thus partly controlled by access to resources (including lithic ones, but mainly food and water). The Holocene inhabitants however showed an ability to adapt themselves to their sometimes extreme environment, which is characteristic of many people from desert regions, being very cold or very warm. Then, if the image of a rather isolated area is not too distant from an archaeological reality at certain times, it is fundamental not to consider it as depopulated and without interest for the comprehension of regional prehistory on a wider scale.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the organizers of the international conference on the history of climate and environmental deserts of Africa and Arabia, particularly Anne-Marie Lézine for her invitation and Serge Cleuziou, as well as the French Academy of Sciences in Paris.

The work described from Hadramawt has been undertaken within two research projects. I am happy to warmly thank the RASA Project directors: Joy McCorriston, Eric Oches, Abdulaziz bin Aqil, and also the French Archaeological Mission in Jawf-Hadramawt directors: Michel Mouton, Frank Braemer, Anne Benoist.

For their comments and general discussion about South Arabian prehistory, I gratefully acknowledge the help of Pierre Bodu, Vincent Charpentier, Marie-Louise Inizan, Edward J. Keall, Lamya Khalidi, Louise Martin, Joy McCorriston, Michael D. Petraglia, Jérémie Schiettecatte. I finally thank the Fondation Fyssen for providing financial support for my stay in Cambridge, and I thank the LCHES staff for their warm welcome, especially Michael Haslam for re-reading the English version of this text.