1 Introduction

Fossil plant remains, such as leaf impression or charcoals of tropical trees in Holocene deposits from Sudan and northern Niger, several hundred kilometres north of their modern distribution [49,83], as well as widespread forest relicts from the edge of the Guineo-Congolian forest to the Saharan desert [36], provide evidence for the former expansion of tropical forest ecosystems in West Africa. This has been related to the orbitally-induced increase in Atlantic monsoon rains during the Early Holocene [6,31]. The forest-savanna ecotone may have been displaced north by 350 km compared to the present [1], while the northern limit of the Sudanian zone of woodlands and the Sahelian zone of wooded grasslands may have been displaced by at least 4° (450 km) [60]). In a review paper, Hoelzmann et al. [26] suggest that the boundary between steppes and wooded grasslands was situated around 20°N in western Sahara and 25°N in eastern Sahara, and that steppes expanded widely to 30°N during the mid-Holocene. Pollen data confirm that a significant number of tropical tree species were present in the Saharan region during the Holocene [38]. This period, marked by a strong environmental change, with a high number of lakes and wetlands and occurrence of tropical humid plants in a region that is nowadays arid, is called the “green Sahara”. The tropical humid species however rarely exceed 1% in any of the pollen sequences from the Sahara, which remained dominated by grasses. That clearly points to a major issue regarding past vegetation and plant dynamics in response to climate change: can the environmental history of West Africa be summarized as the migration of existing vegetation zones, or have tropical species behaved individually? Could we, from the available paleodata, estimate the migration rates of the main tropical tree species recovered in the Holocene sediments from the Saharan desert? In this paper, we use the data set of well-dated pollen sites from the African Pollen Database (APD) to discuss vegetation dynamics, migration rates and plant community composition within the Sahara during the Holocene Humid Period.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Pollen and plant data

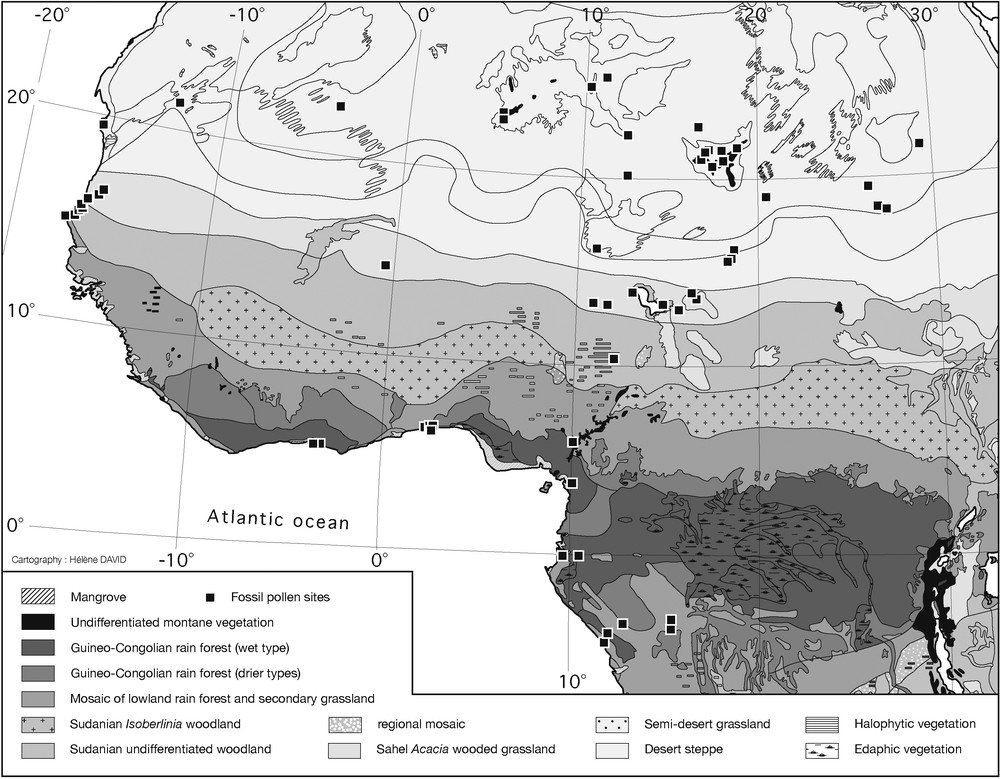

The set of fossil pollen data includes 73 terrestrial sites located between 4.3°S and 25.5°N in western Africa (Fig. 1; Table 1), with 28 sites from the modern Saharan desert, 19 sites from the Sahel, 10 sites from the Sudanian zone of dry forests and woodlands and 16 sites from the Guineo-Congolian zone of forests. In this article, we refer to different plant ecosystem types, using terms like steppe or wooded grassland: steppe refers to more or less open low herbaceous formations; wooded grassland refers to dense herbaceous formations including widespread trees and shrubs [82]. Given the truncated nature of most of the lacustrine sedimentary sequences not only in arid areas [36] but also near the equator [77], very few of these sites display a continuous Holocene sequence, with 27 of them having only one dated sample. The 14C measurements were converted into calendar ages (cal years BP) using calibration from [4] and [52]. Age models were calculated by linear interpolation between two dated levels, taking into account sedimentary discontinuities and chronological uncertainties linked to the hard water effect [20].

Location of pollen sites in West and central Africa. Note the lack of data between 5 and 10°N. African vegetation map from [82].

Localisation des sites polliniques en Afrique occidentale et centrale. Noter l’absence de données entre 5 et 10°N. Carte de végétation de l’Afrique tirée de [82].

Liste des sites palynologiques disponibles dans l’African Pollen Database (APD) et localisés au Sahara, en Afrique occidentale et en Afrique centrale le long de la côte Atlantique.

| Site Name (APD) | Longitude (decimal) | Latitude (decimal) | Altitude (Depth [m]) | Country | Time interval | References | |

| Amekni | 5.52 | 22.79 | 1000 | Algeria | 7693 | Guinet and Planque [24] | |

| Taessa (Hoggar) | 5.51 | 23.16 | 2150 | Algeria | 5661.5 | Ballouche et al. [3]; Thinon et al. [74]; Pons and Quézel [50] | |

| Dangbo | 2.38 | 6.54 | 40 | Benin | 0 | 8371.3 | Tossou [75] |

| Goho | 2.58 | 6.44 | 35 | Benin | 887.4 | 7560 | Tossou [75] |

| Lake Sélé | 2.43 | 7.15 | NA | Benin | 274 | 8367 | Salzmann and Hoelzmann [66] |

| Lake Nokoué | 2.39 | 6.50 | 47 | Benin | 2330.7 | 8175.7 | Tossou [75] |

| Yéviédié | 2.38 | 6.54 | 53 | Benin | 1326.8 | 7926 | Tossou [75] |

| Oursi | −0.49 | 14.66 | 290 | Burkina Faso | 0 | 3264.74 | Ballouche and Neumann [2] |

| Lake Ossa [OW4] | 10.75 | 3.80 | 8 | Cameroon | 28.7 | 5406.9 | Reynaud-Farrera et al. [56]; Reynaud-Farrera [54,55] |

| Lake Ossa 1 | 10.02 | 3.78 | 8 | Cameroon | 15 | 635 | Reynaud [53]; Reynaud-Farrera [54] |

| Shum Lake | 10.05 | 5.85 | 1355 | Cameroon | 464 | 32420.44 | Kadomura [32] |

| Bois de Bilanko [LH1] | 15.35 | −3.52 | 600 | Congo | 966.6 | 5467.3 | Elenga [12] |

| Bois de Bilanko [LH3] | 15.35 | −3.52 | 600 | Congo | 2707.5 | 39380.5 | Elenga [12] |

| Bois de Bilanko [LS3] | 15.35 | −3.52 | 600 | Congo | 12861 | Elenga [12]; Elenga and Vincens [13]; Elenga et al. [14] | |

| Coraf 1 | 11.85 | −4.75 | 0 | Congo | 0 | 3506 | Elenga [12]; Elenga and al. [15] |

| Coraf 2 | 11.85 | −4.75 | 1 | Congo | 930 | 2978 | Elenga [12] |

| Lake Kitina [KT3] | 12.00 | −4.27 | 120 | Congo | 200.9 | 6283 | Elenga et al. [17] |

| Lake Sinnda [SN 2] | 12.80 | −3.84 | 128 | Congo | 450.9 | 6467 | Vincens et al. [76] |

| Lake Sinnda [SN 3] | 12.80 | −3.84 | 128 | Congo | 0 | 4714.1 | Vincens et al. [76] |

| Ngamakala 2 | 15.38 | −4.08 | 400 | Congo | 495 | 23908.7 | Elenga [12] |

| Ngamakala 4 | 15.38 | −4.07 | 400 | Congo | 13178.8 | 28468.5 | Elenga et al. [15]; Elenga et al. [16] |

| Songolo | 11.86 | −4.76 | 5 | Congo | 2761 | 7978 | Fabing [19]; Elenga et al. [18] |

| Assinie | −3.32 | 5.13 | 0 | Ivory Coast | 8905 | Frédoux and Tastet [22]; Frédoux [21] | |

| IVCO3 | −3.52 | 5.10 | 0 | Ivory Coast | 10979 | Frédoux and Tastet [22]; Frédoux [21] | |

| Messak Settafet | 11.43 | 25.43 | 1100 | Libya | 4701.5 | Schulz [71] | |

| Uan Afuda Cave | 10.50 | 24.87 | 922 | Libya | 8837 | 9307 | Mercuri [46] |

| Uan Muhuggiag | 10.50 | 24.83 | 915 | Libya | 4150 | 7697 | Mercuri et al. [48] |

| Uan Tabu | 10.52 | 24.86 | 915 | Libya | 4217 | 9745 | Mercuri and Grandi [47] |

| Sebkha de Taoudenni | −4.00 | 22.67 | 120 | Mali | 6464.5 | Cour and Duzer [8] | |

| Baie de Saint Jean | −16.30 | 19.46 | 0 | Mauritania | 1777.5 | 3635 | Lézine (unpublished) |

| Sebkha de Chemchane | −12.21 | 20.93 | 256 | Mauritania | 7590.5 | 9131.4 | Lézine [34,37]; Lézine et al. [42] |

| Ari Koukouri 85 | 13.10 | 13.92 | 270 | Niger | 7249.5 | Schulz [72]; Schulz et al. [73] | |

| Ari Koukouri 88 | 13.10 | 13.92 | 270 | Niger | 5488 | 9617.4 | Schulz [72]; Schulz et al. [73] |

| Nebenwadi - Enneri Achelouma 12 | 12.70 | 22.35 | 650 | Niger | 7805.5 | Schulz [71] | |

| Seguedine | 12.78 | 20.16 | 412 | Niger | 8776.5 | Baumhauer and Schulz [5] | |

| Termit | 11.07 | 16.20 | 450 | Niger | 9981 | Schulz et al. [73] | |

| Kaigama Oasis | 11.56 | 13.25 | 300 | Nigeria | 3567.39 | 11111.93 | Salzmann [62]; Salzmann and Waller [65] |

| Kajemarum Oasis | 11.18 | 13.30 | 300 | Nigeria | 2844.68 | 11027.33 | Holmes et al. [27]; Salzmann and Waller [65]; Salzmann [63]; Waller and Salzmann [80] |

| Kuluwu Oasis | 11.55 | 13.21 | 330 | Nigeria | 4703.3 | 11405.6 | Salzmann [62]; Salzmann and Waller [65] |

| Lake Bal | 10.93 | 13.30 | 300 | Nigeria | 341.37 | 11905.13 | Salzmann and Waller [65]; Holmes et al. [28]; Salzmann [63]; Waller and Salzmann [80] |

| Lake Tilla | 12.11 | 10.38 | 690 | Nigeria | 247.85 | 13063.98 | Salzmann [63,64]; Salzmann et al. [67] |

| Diogo 1 | −16.80 | 15.26 | 8 | Senegal | 0 | 10826.47 | Lézine [34,35]; Lézine and Chateauneuf [40] |

| Diogo 2 | −16.80 | 15.26 | 8 | Senegal | 485.4 | 11412 | Lézine [34,35]; Lézine and Chateauneuf [40] |

| Lake de Guiers 2 | −15.91 | 16.11 | 0 | Senegal | 0 | 6702.66 | Lézine [34,35] |

| Lake de Guiers 3 | −15.91 | 16.11 | 0 | Senegal | 1121.1 | 6763.77 | Lézine [34,35] |

| Lompoul | −16.71 | 15.35 | 3 | Senegal | 2007.6 | 10321.9 | Lézine [34,35]; Lézine and Chateauneuf [40] |

| Potou | −16.50 | 15.75 | 11 | Senegal | 193.2 | 11399.2 | Lézine [34,35]; Lézine and Chateauneuf [40] |

| Thiaye | −17.50 | 14.92 | 1 | Senegal | 5593.23 | 6371.44 | Lézine [34]; Lézine et al. [41]; Chateauneuf et al. [7] |

| Touba Ndiaye 2 | −16.86 | 15.16 | 6 | Senegal | 1208 | 12850 | Lézine [34,35]; Lézine and Chateauneuf [40] |

| Bir Atrun | 26.65 | 18.16 | 600 | Sudan | 6469.47 | 10228.53 | Ritchie [57]; Ritchie and Haynes [60] |

| El Atrun | 26.00 | 18.00 | 600 | Sudan | 10334 | Jahns [30] | |

| Oyo | 26.45 | 19.30 | 510 | Sudan | 5186.9 | 10363 | Ritchieet al. [61]; Ritchie [58] |

| Selima Oasis | 29.30 | 21.36 | 270 | Sudan | 7643.18 | 11021.4 | Ritchie and Haynes [60]; Haynes et al. [25] |

| Angéla-Kété | 18.35 | 15.83 | NA | Chad | 25260.5 | Maley [43] | |

| Enneri Bardagué | 16.91 | 21.41 | NA | Chad | 9294 | Schulz [69,70] | |

| Enneri Dirennao | 17.17 | 21.52 | 1135 | Chad | 8380 | Schulz [69,70,71] | |

| Enneri Tabi | 17.05 | 21.33 | NA | Chad | 10523 | 12357 | Schulz [71] |

| Fourtchiak Sud Ouest | 18.27 | 15.95 | NA | Chad | 24516.5 | Maley [43] | |

| Kamala | 15.00 | 14.00 | NA | Chad | 11783.5 | Maley [43] | |

| Kouka | 15.51 | 13.11 | 283 | Chad | 11002 | Maley [43] | |

| Mandi | 14.76 | 13.41 | 276 | Chad | 11352 | Maley [43] | |

| Mouskorbé | 18.53 | 21.36 | 2600 | Chad | 7472.5 | 9443 | Maley [43] |

| Nemra | 18.55 | 16.30 | NA | Chad | 27000 | Maley [43] | |

| Ounianga | 20.52 | 19.05 | 380 | Chad | 0 | 6033.5 | Lézine (unpublished) |

| Tamarisken-Hügel - Bardagué | 16.61 | 22.73 | NA | Chad | 1786 | Schulz [71] | |

| Tarso Yega | 17.48 | 20.83 | 2200 | Chad | 7718.5 | Maley [43] | |

| Tarso Yega [Gavr I] | 17.50 | 20.66 | NA | Chad | 8929.5 | Schulz [69,70,71] | |

| Tibesti Gabrong | 17.10 | 21.75 | NA | Chad | 8948.5 | Schulz [69,70,71] | |

| Tjéri | 16.50 | 13.73 | 275 | Chad | 565 | 10093.5 | Maley [43,45] |

| Tjolumi | 18.13 | 21.52 | 1115 | Chad | 6647 | Schulz [69,70,71]; Gabriel [23] | |

| Trou au Natron 688_690 | 16.50 | 20.00 | 1850 | Chad | 18188.5 | Maley [43] | |

| Trou au Natron Erg T63-64_Ka46 | 16.75 | 21.00 | NA | Chad | 15262.5 | Schulz [71] | |

| Yebbi Bou - Yebbigué [Gr A; Gr B] | 18.03 | 20.86 | 1440 | Chad | 9136 | Schulz [69,70,71] |

After homogenization of the pollen nomenclature [79] and grouping of closest pollen types, a list of 476 pollen taxa was obtained including 261 trees, shrubs and lianas, 105 herbs and 109 undifferentiated pollen types. Thirty-three tree and shrub pollen taxa were selected on the basis that they were found in at least two pollen sites and are thought to indicate regional environmental conditions (Table 2, [38]). The present analysis focuses on a selection of 11 of them to illustrate the main plant distribution patterns in the Holocene Saharan region and to provide critical information for understanding vegetation dynamics in the tropics. Both pollen presence and percentage data are presented, the latter being calculated against a sum excluding indeterminable pollen grains.

Liste des types polliniques d’arbres présents dans au moins deux sites sahariens au cours des 14 000 ans. Les taxons sont classés en fonction de leur affinité phytogéographique.

| Phytogeographic affinity | Family | Pollen type | Number of occurrences of each pollen type in the pollen sites located North of 18°N |

| Saharan-Mediterranean | Rhamnaceae | Rhamnaceae undifferenciated | 2 |

| Saharan-Mediterranean | Ephedraceae | Ephedra | 19 |

| Saharan | Polygonaceae | Calligonum polygonoides | 6 |

| Saharan | Boraginaceae | Moltkiopsis ciliata | 7 |

| Saharan | Salvadoraceae | Salvadora | 10 |

| Saharan | Salvadoraceae | Salvadoraceae undiff. | 7 |

| Saharan | Tamaricaceae | Tamarix | 14 |

| Saharan | Rhamnaceae | Ziziphus/Rhamnus | 9 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Mimosaceae | Acacia | 21 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Balanitaceae | Balanites | 9 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Capparidaceae | Boscia/Cadaba | 9 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Capparidaceae | Capparis | 8 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Menispermaceae | Cocculus | 5 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Burseraceae | Commiphora | 7 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Capparidaceae | Maerua/Ritchiea | 12 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Chenopodiaceae | Nucularia perrini | 2 |

| Tropical-Sahelian | Menispermaceae | Tinospora bakis-type | 2 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Euphorbiaceae | Alchornea | 3 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Palmae | Borassus/Hyphaene | 3 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Ulmaceae | Celtis | 11 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Combretaceae | Combretaceae undiff. | 12 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Rubiaceae | Mitragyna-type inermis | 2 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Myrtaceae | Eugenia/Syzygium | 3 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Euphorbiaceae | Flueggea | 3 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Anacardiaceae | Lannea/Sclerocarya | 5 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Caesalpiniaceae | Piliostigma | 4 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Anacardiaceae | Rhus/Antrocaryon/Pseudospondias | 8 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Ebenaceae | Diospyros | 1 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Hymenocardiaceae | Hymenocardia | 1 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Euphorbiaceae | Macaranga/Mallotus/Mareya | 1 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Palmae | Phoenix | 2 |

| Tropical-Sudanian | Anacardiaceae | Anacardiaceae undiff. | 2 |

| Tropical | Mimosaceae | Mimosaceae undiff. | 3 |

| Tropical | Moraceae | Ficus | 5 |

| Temperate | Betulaceae | Alnus | 7 |

| Temperate | Aceraceae | Acer | 3 |

| Temperate | Betulaceae | Betula | 9 |

| Temperate | Pinaceae | Cedrus | 2 |

| Temperate | Corylaceae | Ostrya/Carpinus orientalis-type | 5 |

| Temperate | Salicaceae | Populus | 2 |

| Temperate | Ulmaceae | Ulmus | 3 |

| Temperate | Tiliaceae | Tilia | 5 |

| Temperate-Mediterranean | Cupressaceae | Cupressaceae undiff. | 5 |

| Temperate-Mediterranean | Vitaceae | Vitis-type vinifera | 2 |

| Temperate-Mediterranean | Fabaceae | Ulex-type | 3 |

| Temperate-Mediterranean | Asparagaceae | Asparagus-genre | 2 |

| Mediterranean-Montainous | Oleaceae | Olea | 10 |

| Mediterranean-Montainous | Oleaceae | Oleaceae undiff. | 5 |

| Mediterranean-Montainous | Cupressaceae | Juniperus/Cupressus | 10 |

| Mediterranean-Montainous | Ericaceae | Ericaceae undiff. | 8 |

| Mediterranean | Caesalpiniaceae | Ceratonia oreothauma | 3 |

| Mediterranean | Myrtaceae | Myrtus | 3 |

| Mediterranean | Apocynaceae | Nerium oleander | 2 |

| Mediterranean | Caesalpiniaceae | Cercis | 2 |

As the determination of pollen is usually made at the genus or family levels, a given taxon may correspond to several plant species [79,81]. As a consequence, the list of all plants corresponding to each pollen taxon was established and the location of each individual plant record in West Africa was extracted from floras, botanical inventories or plant databases. Information from these different sources does not take into account the abundance of the species and the absence of a plant location point does not necessarily correspond to the absence of the species at that location [81]. Only the occurrence of each plant species was considered to draw the modern distribution maps of plants corresponding to the selected pollen types.

2.2 Statistical analyses

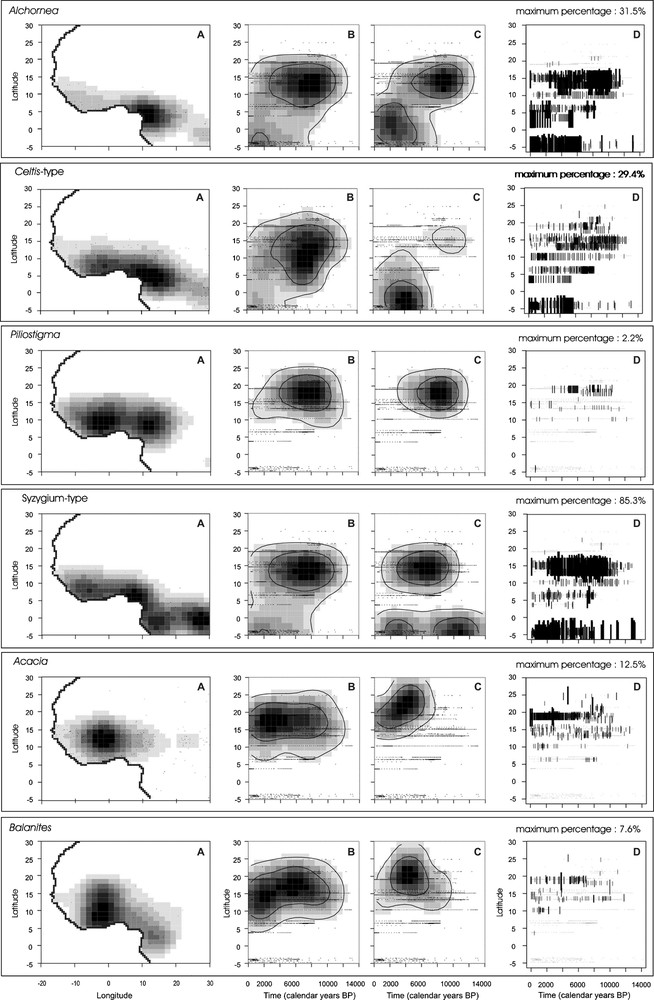

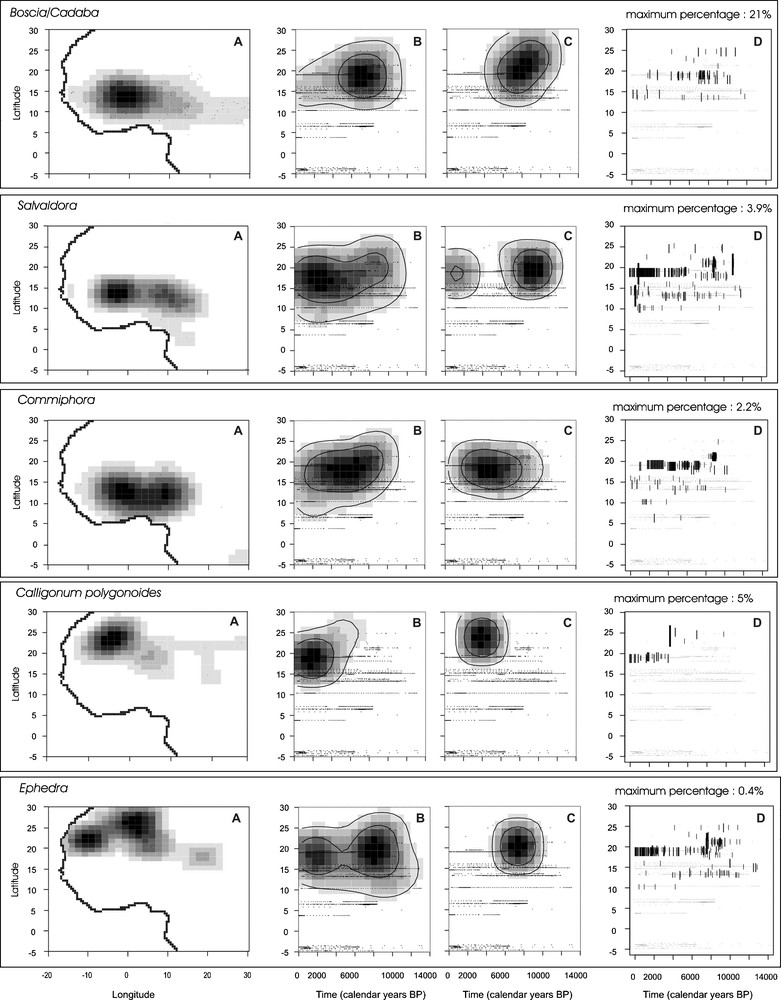

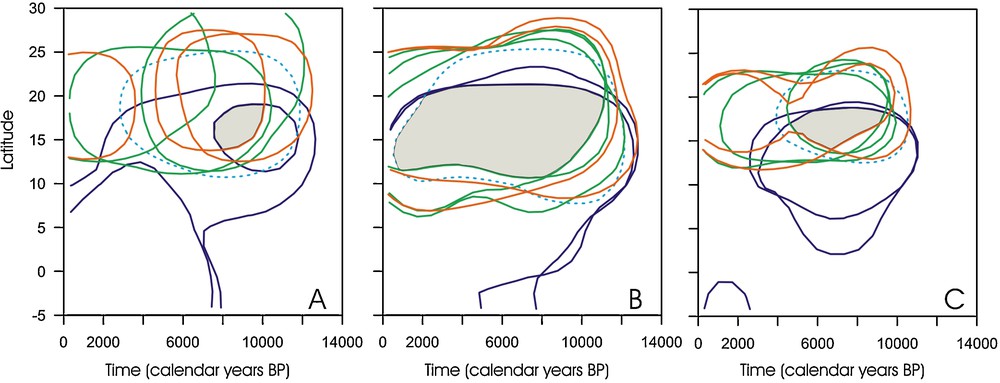

Due to the wide geographical dispersion of pollen sites in West and central Africa, data are presented according to time and latitude, only. Two probability density functions [33,68] were calculated for each pollen taxon using respectively the distribution of pollen presence and the distribution of pollen percentages (Fig. 2B and C). Two probability thresholds were defined as the limit of the most probable occurrence of a pollen taxon in this spatiotemporal space: the 85% threshold displays the most similar contour compared to the limit of the presence whereas the 50% threshold points to the maximum of the distribution.

Comparison between the latitudinal distribution of 11 selected fossil pollen taxa during the last 14,000 cal years BP and the present distribution of the corresponding plant taxa. A. Probability density functions established from the plant occurrences in West and central Africa. “.” symbolises each plant record. B. Probability density functions established from pollen taxon presence in the fossil assemblages. C. Probability density functions established from pollen percentages. D. Distribution of the pollen percentages of each taxon according to latitude and time. Size and thickness of the black lines are proportional to pollen percentages. The maximum percentage is indicated for each taxon. Masquer

Comparison between the latitudinal distribution of 11 selected fossil pollen taxa during the last 14,000 cal years BP and the present distribution of the corresponding plant taxa. A. Probability density functions established from the plant occurrences in West and central Africa. “.” ... Lire la suite

Comparaison entre la distribution latitudinale des 11 taxa sélectionnés dans cette étude au cours des derniers 14 000 ans et la répartition actuelle des plantes correspondantes. A. Densité de probabilité à partir de la présence des plantes en Afrique occidentale et centrale. Le « . » symbolise chaque présence de plante. B. Densité de probabilité à partir de la présence du pollen dans les assemblages fossiles en Afrique occidentale et centrale. C. Densité de probabilité à partir du pourcentage du pollen. D. Répartition des pourcentages polliniques de chaque taxon selon le temps et la latitude. La taille et l’épaisseur de chaque trait noir sont proportionnelles à la valeur du pourcentage. Le pourcentage maximum atteint par chaque taxon est indiqué. Masquer

Comparaison entre la distribution latitudinale des 11 taxa sélectionnés dans cette étude au cours des derniers 14 000 ans et la répartition actuelle des plantes correspondantes. A. Densité de probabilité à partir de la présence des plantes en Afrique occidentale et centrale. Le ... Lire la suite

This probability space does not mean that the corresponding plants occupied the entire space during the past, but only that they may have occurred at this latitude. We used the same representation for the current distribution of plants to determine their probability density function over West Africa along longitude and latitude (Fig. 2A). All the analyses presented in this work were carried out using the open source R software2.

3 Results: modern versus Holocene distribution of plants

3.1 Tropical humid plant types

The tropical humid pollen taxa include plant species with Guineo-Congolian, Guineo-Sudanian and Sudanian phytogeographical affinity. The modern distribution of tropical humid pollen types such as Celtis-type, Alchornea, Syzygium-type and Piliostigma, and their assigned climate spaces have been analyzed in detail in a previous study [81]. Except Piliostigma, which characterizes more open ecosystems of woodlands and wooded grasslands, all these tropical humid pollen types may occur in a wide range of wooded or forested habitats including swamp and gallery forests from the Guineo-Congolian to the Sahelian vegetation zones [78]. Their modern distribution in western Africa does not exceed 16–18°N to the north. Pollen grains from the corresponding species are found in Holocene sediments up to 20 to 25°N (Fig. 2B–D), i.e., 3° to 7°N of their northernmost present-day distribution (Fig. 2A). Moreover, probability density functions calculated from presence and percentage data confirm that the more humid plant types, Alchornea, Celtis-type and Syzygium-type, have been present near the equator in their current zone of distribution since 14,000 cal years BP [38]. Their penetration into areas currently under Sahelian and Saharan climates started roughly around 12,500 cal years BP, with specific taxa patterns: as a pioneer plant type, Alchornea expanded widely in the Early Holocene and reached its maximum abundance (27.9%) from 11,200 to 4600 cal years BP between 9° and 18°30′N, before its southward retreat during the Mid- to Late Holocene. Celtis-type also widely expanded throughout West Africa, but it remained of scattered occurrence with low abundance values (maximum = 4%). Its northernmost expansion occurred from 11,800 to 7600 cal years BP, spreading from 12° to 19°N. As compared to Alchornea and Celtis-type, the expansion of Syzygium-type within the Sahel and the Sahara was delayed by 1000 years (roughly 10,600 cal years BP), with its maximum abundance being recorded from 9400 to 2800 cal years BP between 9° and 19°N. Piliostigma displays a slightly different history since it has never been significantly present south of 10°N. During the Holocene, its maximum expansion occurred from 11,000 to 5500 cal years BP between 13° and 23°N (maximum = 2%).

3.2 Sahelian plant types

The modern Sahelian and Sahelo-Saharan wooded grasslands are characterized by the occurrence of Acacia, Commiphora, Balanites, Salvadora and Boscia-Cadaba pollen types [81]. During the Holocene, their northernmost occurrence was located up to 25°N in southern Libya, recording similar northward migration as the more humid Sudanian plant types. Probability density functions on pollen presence show that Acacia (maximum abundance of 12% reached at 22°N around 7800 cal years BP), Balanites (maximum abundance of 7.6% reached at 19°N around 3800 cal years BP) and Salvadora (maximum abundance of 20% reached at 21°N around 11,000 cal years BP) have expanded widely within the Saharan region since 12,000 cal years BP, while Commiphora and Boscia-Cadaba started their expansion roughly 500 to 1000 years later (with maximum percentages of 2.2% and 3.9%, respectively, reached at 19°N). While Acacia distribution remained relatively stable through time, Commiphora, Balanites, Salvadora and Boscia-Cadaba progressively retreated southward after 4500 cal years BP to reach their present-day position. Probability density functions from pollen percentages (Fig. 2C, 3.5 to 3.9) show that the more xeric plant types (Salvadora and Boscia-Cadaba) reached their maximum expansion earlier (11,500–11,000 cal years BP) than Commiphora, Balanites and Acacia for which the northernmost expansion successively occurred during a time interval spanning 8300 to 6300 cal years BP.

3.3 Saharan plant types

Calligonum and Ephedra are among the most “arid” types recovered in desert areas. They are currently found on sand dunes (e.g., “grand erg” in Algeria), up to the edge of the Mediterranean Sea to the north. Ephedra is also a characteristic component of mountain plant communities from the central Sahara. To the south, their area of distribution is delimited by the tropic of Cancer, except for one occurrence of Calligonum recorded at 18°N near Faya [51]. The Holocene distributions of these two plant types differs considerably from one another: Ephedra has been regularly present from 13,000 cal years BP to the present with a maximum density between 9000 and 5500 cal years BP (maximum abundance of 9.5% reached around 7500 cal years BP at 21°N), whereas the expansion of Calligonum took place later, between 6000 and 2000 cal years BP (maximum of 5% reached at 25°N around 4200 cal years BP), with a southward expansion to roughly 20°N during the last four millennia.

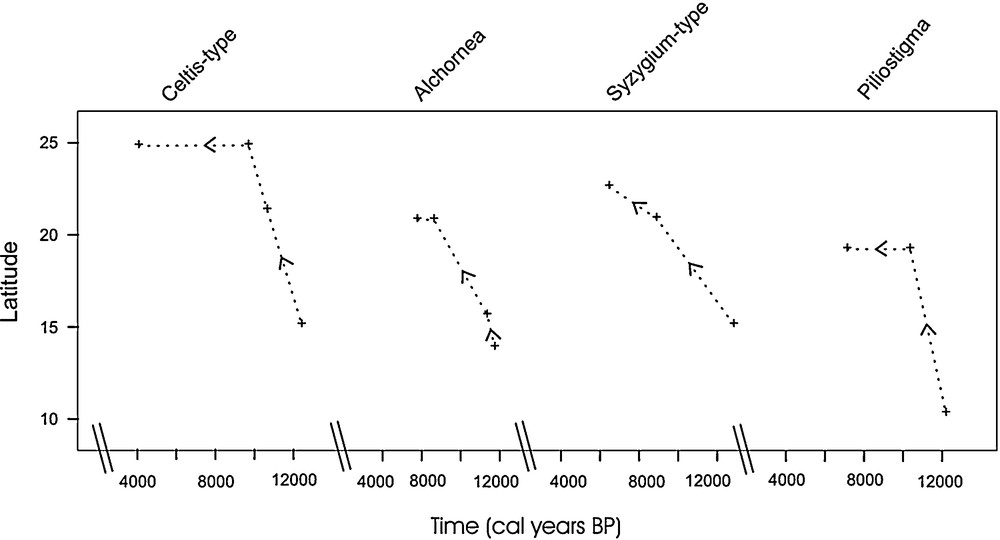

4 Analysis: the migration rate of tropical plant types

Estimates of migration rates of tropical forest trees during their post-glacial northward movement is severely limited both by the scarcity of data, particularly between 5°S and 10°N, and by the incompleteness of the sedimentary records. Moreover, the Early Holocene period follows the Last Glacial Maximum at the end of the Late Pleistocene, which has been estimated as a period marked by a dry climate, related to the retreat of the tropical humid vegetation near the equator and the southern extension of the Sahara/Sahel boundary to 14°N [10,11,44]. The migration of the tropical humid plants in the Early-Mid Holocene probably started from the low latitudes of central Africa [1,38,39,84], but with the available fossil pollen data, we are only able to estimate the end of their progression, when they entered in the Sahara region. Taking into account the plant communities as a whole, Lézine [38] estimated that tropical plants entered the Saharan region roughly 7000 years after the onset of the Holocene Humid Period at 15,500 cal years BP. Here, we examine the first appearance of pollen grains from four selected tropical plant types and compare their migration rates and colonization patterns north of 10°N (Fig. 3):

- • the first occurrence of Celtis-type in the Sahel is reported at Touba N’Diaye (15°10′N) at 12,450 cal years BP. It has also been registered at the same time at Tilla (10°23′ N). It was then reported at Selima (21°22′ N) at 10,700 cal years BP. Its northernmost occurrence was recorded in southern Libya at roughly 25°N between 9900–9500 cal years BP. Inferred migration rate estimates varied little around 400 m/year;

- • Syzygium-type was present at Touba N’Diaye (15°10′N) as early as 12,850 cal years BP and at Tilla (10°23’N) 500 years later. Owing to age-model uncertainties at the base of the Touba N’Diaye series, the expansion of Syzygium-type was probably simultaneous at both sites. It was reported at Diogo (15°16′N) at 11,410 cal years BP, then at Chemchane (20°56′N) at 8900 cal years BP and at Taoudenni (22°6′N) at 6500 cal years BP. Inferred migration rate estimates varied from 600 m/year in the Sahel to 150 m/year in the Sahara;

- • Alchornea appeared roughly simultaneously between 10°23′N (Tilla) and 14°02′N (Kamala) around 11,850–11,780 cal years BP. Then, it rapidly expanded to the west in the Niayes interdunes (15°–16°N) around 11,500–11,400 cal years BP. Its northernmost occurrence was first at el Atrun (18°10′N) at 10,330 cal years BP and then at Chemchane (20°56′N) at 8700 cal years BP. Inferred migration rate estimates averaged 505 m/year (460–570 m/year) in the Sahel and 200 m/year (235–195 m/year) in the Sahara;

- • Piliostigma's northward movement started at 12,200 cal years BP at 10°23′N (Tilla). It reached the Manga region (Bal – 13°18′N) at 11,250 cal years BP before expanding widely throughout eastern Sahara, with its earliest occurrence dated from 10,360 cal years BP (Oyo – 19°15′N). Inferred migration rates estimates averaged from 340 m/year in the Sahel to 740 m/year in the Sahara.

Northward migration of the tropical pollen types. Pollen occurrences are represented with the “+” symbol, and the dashed line represents their estimated displacement. Pollen types have been ordered according to the date of first probable appearance at 20°N.

Migration des types polliniques tropicaux en direction des latitudes sahariennes. La présence de chaque type est indiquée par une croix et la ligne interrompue figure son déplacement potentiel. Les types polliniques sont présentés en fonction de leur arrivée au-delà de 20°N.

These examples demonstrate that the northward progression of tropical trees throughout northern Africa did not follow a single trend: as pioneer plant types, Alchornea, Piliostigma and Celtis-type moved rapidly toward the northern tropic. The northward progression of Syzygium-type was comparatively slower. Mean values of migration rates presented here are only indicative, as they do not fully represent the real migration of the plants in the region, but only the probable northward migration estimated along latitudinal gradients from a limited number of pollen sites. Interestingly, they do not differ greatly from earlier pollen-based estimates of postglacial spread of temperate trees, such as the movement of spruce across northern America (200–376 m/year [9,59]) or northern Europe (500 m/year [29]).

5 Discussion: the “green Sahara”

Superimposed curves of probability density functions of all selected pollen types characteristic of the Sudanian, Sahelian and Saharan plant communities through time and latitude (Figs. 4 and 5) show that tropical humid plants started to expand northward since 12,000 cal years BP at 15°N and reached their maximum from 10,000 to 8000 cal years BP. They then remained present at this northernmost latitude until 5000 cal years BP, although they were more scattered at that time. Except for plants whose growth may have been favoured by soil humidity (Syzygium-type) and which may have persisted along rivers or fresh water bodies, all tropical humid taxa retreated progressively south during the last 4000 years. During this latter period, Alchornea and Celtis-type density functions followed a similar decreasing trend, whereas Piliostigma maxima persisted in northern latitudes, confirming its adaptation to more xeric environmental conditions. Density probability functions for Saharan plant types (Ephedra) display an opposite trend with maxima reached at 25°N most of the time. Their southward expansion started from 7000 cal years BP and increased during the last 4000 years to reach 10–15°N. As expected, maxima of probability density functions for Sahelian and Sahelo-Saharian elements occur within an intermediate latitudinal range centred around 18°N. At this latitude, their maxima were reached from 11,000 to 8000 cal years BP; they then moved northward (ca 20°N) during the last 4000 years. Acacia displays a specific pattern since the highest values of probability density functions calculated from percentages arose between 6000 and 3000 cal years BP at 20–25°N. Probability densities calculated on pollen presence however did not confirm such northward progression.

Latitudinal distribution of selected pollen taxa from 14,000 to 1000 years BP. Curves show probability densities calculated from pollen percentages (normalised for each taxon and varying from 0 to 1).

Répartition latitudinale des taxons sélectionnés dans notre étude de 14 000 à 1000 ans BP. Les courbes montrent les densités de probabilité calculée à partir du pourcentage pollinique (normalisées pour chaque taxon et variant entre 0 et 1).

Common space (in grey) occupied by tropical humid (Guineo-congolian and Sudanian), Sahelian and Saharan taxa. A. Probability density functions from the pollen percentages. The selected threshold, taken as the limit of the potential presence of the corresponding plants, corresponds to 85% of the total distribution of each taxon. B. Probability density functions from pollen presence (threshold = 85%). C. Probability density functions from pollen percentages (threshold = 50%).

Espace commun (en gris) occupé par les taxons soudaniens, sahéliens et sahariens. A. Densité de probabilité calculée à partir du pourcentage pollinique. Le seuil sélectionné figurant la limite de la présence potentielle de la plante correspondante dans l’espace correspond à 58 % du total de la répartition de chaque taxon. B. Densité de probabilité calculée à partir de la présence du taxon (seul = 85 %). C. Densité de probabilité calculée à partir du pourcentage pollinique (seuil = 50 %).

This focus on individual plant species leads to a major conclusion: there is no evidence of one vegetation formation replacing another during the Holocene. Instead, all plants currently characteristic of distinct Saharan, Sahelian and Sudanian communities were able to occupy a common space ranging roughly between 12° and 20°N during the Holocene (Fig. 5B). The 85% probability threshold allows restriction of this common spatiotemporal space between 14° and 19°N from 10,000 to 7500 cal yrs BP (Fig. 5A) or 9500 to 4500 cal years BP (Fig. 5C) depending on the calculation method used. That suggests that the direct consequence of increased rainfall during the African Humid Period was an increase in biodiversity, since Saharan ecosystems accommodated more humid adapted plant types. For exemple, Celtis-type was among tropical humid taxa that did not form dense forest formations but were probably restricted to gallery forest formations along rivers and fresh water bodies. Our results lead us to question previous assumptions [26] according to which desert plant communities were absent from areas south of 30°N during the Mid-Holocene, and wooded grasslands extended to 25°N in central Africa. We observe here that plant species have responded individually to the climate change, leading to a complex floristic composition not analogue to the present vegetation. The same individual response, associated to unique plant associations, has been observed in temperate region during the last deglaciation, as suggested by the dissimilarity between fossil and modern pollen samples in North America [85].

6 Conclusions

It has been suggested that the direct consequence of the African Humid Period increase in rainfall was the northward displacement of the Sahara/Sahel boundary, which is thought to have reached 23°N in central and eastern Africa. Our study shows that land-surface conditions in the Sahara formed a more complex situation characterized by an increase in biodiversity: plants of the present desert region accommodated more humid-adapted species from tropical forests and wooded grasslands. Tropical plant species, today found some 400 to 500 km southward, probably entered the desert as gallery-forest formations along rivers and lakes where they benefited from permanent fresh water. At the same time, Saharan trees and shrubs persisted, making a complex, “no-analogue” situation. This demonstrates that the vegetation history of the Sahara and the Sahel during the last few thousand of years has not merely been one of migration of the existing vegetation zones. Tropical plant types have intruded into the Saharan region at various rates, suggesting that they behaved individually rather than as a migrating community.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), Commissariat à l’énergie atomique (CEA) and Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR) through the “Sahelp” project. We thank the African Pollen Database contributors for allowing access to pollen data, H. David for drawings, J.-P. Cazet and F. Aptel for assistance. LSCE publication no 4002.