1 Introduction

Radiolarite facies are one of the characteristic features of the Tethyan Mesozoic realm, specifically in the Alpine–Himalayan orogenic belt.

During most of the Mesozoic period, the Tethyan Ocean was widely open and its greatest length was parallel to equator and close to tropical waters. Its southern edge was bordered by parallel basins and ridges, both narrow and elongated on the Arabian plate margin, while the northwestern part showed a more complex pattern of smaller basins and platforms. The stratigraphy of these basins is strongly characterized by the abundance of radiolaritic facies.

Radiolaritic facies in the Tethyan realm have been thoroughly studied for 30 years. Surveys have been presented by De Wever and Dercourt (1985), Baumgartner (1987, 2013), Baumgartner et al. (1995), De Wever et al. (1994, 2001).

Since radiolarites are sometimes found associated with an ophiolitic complex, it had been proposed at the beginning of the nineteenth century (Steinmann, 1905, 1927) to be genetically associated with the silica released by volcanic activity. This idea endured for decades, even though nowadays there are no siliceous sediments along mid-ocean ridges.

Since then, this facies had initially been interpreted as a result of deposition at greater depths below the CCD (Bernoulli and Jenkyns, 1974; Bosellini and Winterer, 1975). Later, it was proposed that radiolarites would preferably be comparable with zones of high bioproductivity (and elevated CCD) such as those related with upwellings (Baumgartner, 2013; Bernoulli and Jenkyns, 2009; De Wever et al., 1994; Jenkyns and Winterer, 1982). An alternative tectonic model for the genesis of radiolarites has also been proposed (Muttoni et al., 2005), in which the siliceous deposits are controlled primarily by plate motion across oceanic zonal circulation patterns.

These siliceous facies have also been compared with some Cenozoic marine diatomaceous deposits from Peru (Pisco Formation), California (Monterey Formation) and from Sicily (Tripoli Formation). However, the main question remaining is: why these radiolaritic facies did not exist during later Cenozoic times?

We deal here successively with the contribution of radiolarians to siliceous deposits in modern oceans, and use these elements to understand what the conditions during pre-Cenozoic times in the Tethyan realm were like. The primary aim of this study is to discuss the importance of monsoon-driven upwelling for radiolarite deposition in the Mesozoic. We analyze the stratigraphic distribution of Mesozoic radiolarites with emphasis on the area from southern Turkey to Oman. This area is particularly interesting, because the radiolarites were deposited along the east coast of the continent; a location that is incompatible with trade winds governed upwelling.

2 Distribution of Tethyan Mesozoic radiolarites in space and time

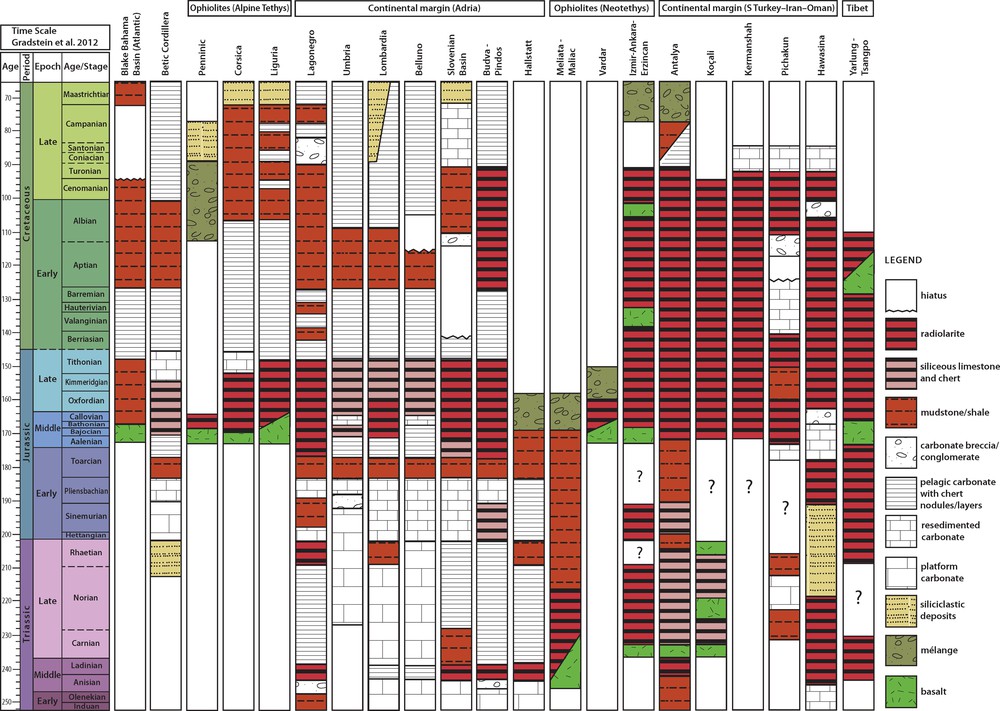

In the Tethyan realm, radiolarites are common from Middle Jurassic to Upper Jurassic, but are also present in several places in Triassic and Cretaceous, or even Permian times (e.g., De Wever et al., 1988a,b, 1990, see Fig. 1). Conversely, Mesozoic radiolarites are missing in the central Atlantic. The most complete Mesozoic radiolarite successions (Fig. 1), reaching up to the Upper Cretaceous, are known from the Pindos–Olonos Zone in Greece (De Wever and Thiébault, 1981), Turkey (Uzuncimen et al., 2011), through Iran (Gharib and De Wever, 2010; Robin et al., 2010) and Oman (Blechschmidt et al., 2004; De Wever et al., 1988b, 1990), and continue further east to Tibet (e.g., Ziabrev et al., 2004).

(Color online.) Chronostratigraphic view showing distribution of silica-rich pelagic lithofacies through the Mesozoic. Time scale after Gradstein et al. (2012). References for the compilation of schematic lithological columns are given in annex, in the electronic supplementary material.

The stratigraphic record (Fig. 1) shows that, regardless of the high ocean fertility, two other conditions must be fulfilled for radiolaritic facies. The first condition is sufficient depositional depth of at least a few 100 meters to allow pelagic sedimentation. The oldest radiolarites overlying shallow-water deposits are systematically related to a rifting event, as is for example the case in the Middle Triassic of the western Neotethys. The second condition is low sediment input from adjacent carbonate platforms or land areas that would dilute or completely replace autochthonous pelagic sedimentation. On Fig. 1, the columns for continental margin basins present their distal facies, but discontinuous record of radiolarites due to occasionally high input of extrabasinal material is still obvious (see, e.g., the columns for the Pichakun and Hawasina basins).

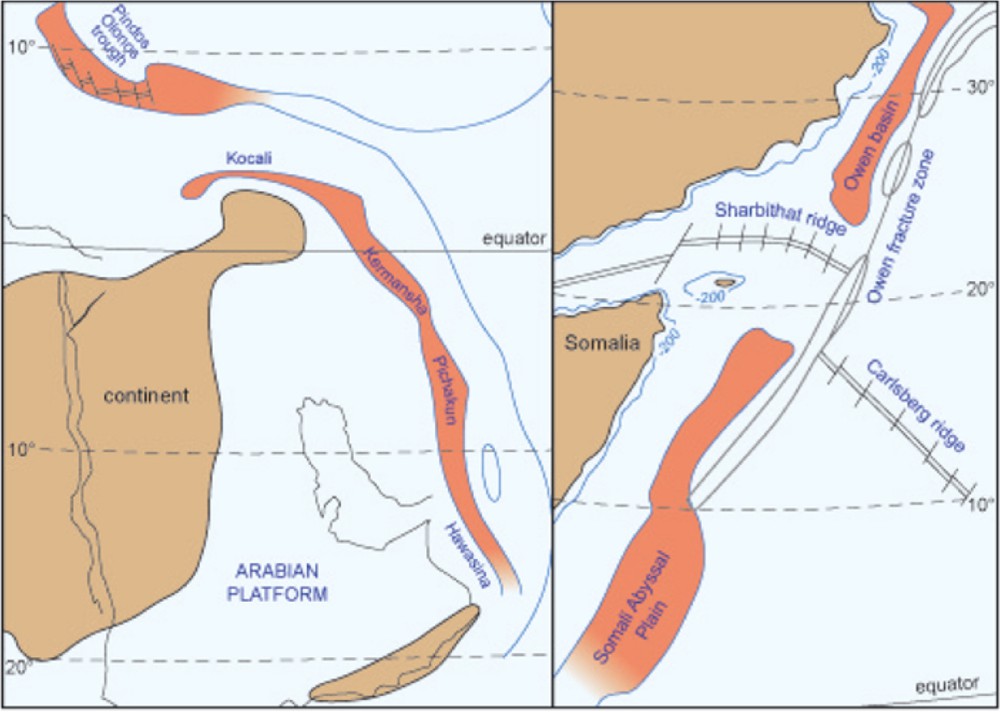

The western borders of the central Neotethys are the main paleogeographical distribution area of radiolarites along continental margin displaying the longest record known. These basins form a continuous elongated belt, which extends from the Hawasina region (Oman, Fig. 2) in the south, through Pichakun (south Iran, Neyriz series), Kermanshah (western Iran) and ends with the Koçali Basin (Turkey). The approximate length of these basins covered more than 3000 km with widths of two or three hundred kilometers. These “gutters” have been compared with the Gulf of Baja California (western part of Mexico) and the Owen Basin (Fig. 3), in the western Indian Ocean (De Wever et al., 1994). These basins show the same size, the same latitude range and the same high biosilicic productivity due to upwellings.

(Color online.) Folded pile of radiolarite in Oman (Hawasina nappes), one of the most complete radiolaritic successions in the world. All are siliceous rocks except the cliffs in background, which are shallow-water limestones of the Oman Exotics.

Photo P. De Wever, DSCN 1771, Oman, 2003.

(Color online.) Comparison at the same scale of Jurassic Tethyan basins of the Pindos–Olonos, Pichakun, Hawasina (left) and the modern Owen and Somali basins in the northwestern Indian Ocean (right). Note their similar size and latitudinal distribution. Like the Somali and Owen basins, the Tethyan basins may have been regions of intense upwelling activity with enriched silica deposits in troughs.

Adapted from De Wever et al., 1994, 2001.

3 Contribution of radiolarians to siliceous deposits in modern oceans

3.1 Geography and depth

Knowledge of present deposition and preservation patterns is of prime importance for paleoceanographical and paleoecological reconstructions.

A detailed study of the vertical distribution of radiolarians at depths ranging from 0 to 2000 m was based on plankton samples collected in filter-collecting devices connected, for 2 months, to pumps at four stations extending west from about the latitude of the US–Mexico border (Kling and Boltovskoy, 1995). Generally, the highest standing stock of living polycystine radiolarians is found in the vicinity of the thermocline (see Takahashi and Ling, 1980; Tanaka and Takahashi, 2008). In general, these studies show that radiolarian species are most abundant and exhibit greatest diversity between 100 and 500 m, but at greater depths the fauna was found to be impoverished.

The geographical distribution of living radiolarians is known from studies based on a combined approach of water column samples and sediment analyses. Radiolarians occur in all seas and in all climatic zones, but the greatest diversity and largest number of radiolarian species occur in the tropics. The abundance of species diminishes towards the poles. Biogeographical studies in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans are primarily based on data from bottom sediments (Boltovskoy et al., 2010).

3.2 Seasonality

Seasonal production of radiolarian species is known from sediment trap experiments. From a 4-year record, Takahashi (1997) noted that total radiolarian fluxes showed significant inter-annual and intra-annual variations, reflecting changes in environmental conditions occurring in the ocean. Radiolarian fluxes generally increased during spring and fall, their timing varied substantially depending on the year, and the spring flux maxima tended to be greater than the fall maxima. The temporal pattern of the total radiolarian fluxes parallels that of siliceous phytoplankton groups, indicating that Radiolaria as a whole can also be considered as productivity indicators. Seasonal radiolarian fluxes result from different factors: diurnal/nocturnal variations, seasonal changes in environmental conditions and, to a lesser extent, impact of zooplankton grazers, El Niño events, and dietary preferences (Boltovskoy, 1994).

3.3 Productivity

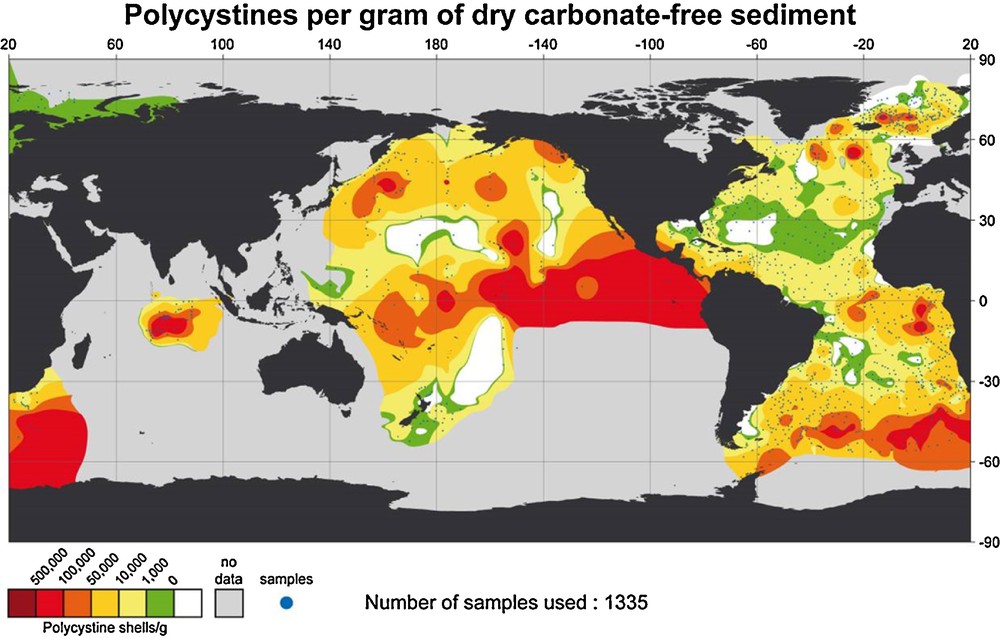

Radiolarians are generally considered to be good indicators of high productivity. This widely held opinion is related to the distribution of radiolarian-rich sediments under the productivity belts of the ocean (Fig. 4). The richest samples contain 100,000 to 500,000 shells per gram of sediment in the equatorial belt, for instance, whereas the middle part of central Atlantic gyre and those in north and south center Pacific contain less than 1000 shells per gram (Boltovskoy et al., 2010). Some species appear to be specifically related to water-masses characterized by high productivity (Nigrini and Caulet, 1992).

(Color online.) Geographical distribution of the numbers of polycystine shells in the surface sediments.

Adapted from Boltovskoy et al., 2010.

Giving a precise view of the total production of radiolarians within the modern ocean remains delicate at the present time due to lack of studies. Nevertheless, some general and preliminary remarks can be made. Minimum values generally range between 10–100 polycystine cells/m3 (in oligotrophic areas) and more than 5000 polycystine cells/m3 (in eutrophic areas). Polycystine fluxes range from less than 500 polycystines/m2/day (in oligotrophic areas, i.e. in the central part of gyres) to more than 20,000 radiolarian polycystines/m2/day (in fertile areas, such as the equatorial upwellings). This approximate distribution shows that radiolarian flux through the water column roughly reflects productivity patterns in the surface waters.

Distribution studies of recent radiolarian species based on sedimentary materials are mainly used for palaeoenvironmental reconstructions. In general, available data show that the biogeographical signal released by the bottom assemblages conveys a fair reflection of the major physical characteristics of near-surface waters.

Since radiolarians are related to increased fertility in surface waters, the abundance and composition of their assemblages can be used to reconstruct changes in paleoproductivity. Higher sedimentation rates of both radiolarians and diatoms are interpreted as resulting from intervals of higher paleoproductivity related to periods of enhanced upwelling activity (De Wever, 1987; De Master, 2002). Several paleontological indices (taxa and their relative proportions) correlate well with variations in geochemical proxies and are also successfully used as indicators of fertility (Jacquot des Combes et al., 1999; Lazarus, 2005).

3.4 Settling

Dead zoo- and phytoplankton, fecal pellets, and animal carcasses originate in the euphotic zone and sink to the bottom of the ocean. Detailed analysis of radiolarian sinking patterns shows that there are two separate sinking processes: accelerated sinking via aggregates and discrete sinking of individuals (Takahashi, 1991). In the North Atlantic, it has been proved that a link exists between the temporary high abundance of radiolarians, the settling of fecal pellets and the organic pulses to depth (Lampitt et al., 2009).

The average residence time of a free radiolarian in the zone of biological production (the upper 200 m of the water column) is from 2 weeks to 1 and a half month (Takahashi and Honjo, 1983). The duration of the settling process for a free test requires from 2 weeks to 14 months in a water column of 5000 m (Takahashi, 1981). The dissolution of a free test may occur in a few hours to a few days (Vinogradov and Tseitlin, 1983). Radiolarians should not reach the bottom, but they do! In fact, during settling, radiolarian tests may be protected from dissolution if they are embedded in fecal pellets or organic aggregates (Casey et al., 1979); similar sedimentation processes have also been invoked for diatoms (Schrader, 1971). This mechanism is very important, because most of the sedimentation occurs that way (e.g., the Santa Barbara Basin, Dunbar and Berger, 1981; Bermuda, Asper et al., 1992). For Vinogradov and Tseitlin (1983), the settling velocity for a free test is estimated at about 100 m/day, while it reaches 1000 m/day when it is embedded within fecal pellets. Contrary to what is known for carbonates, there is no silica compensation depth. As these few remarks clearly show, the chance that a free test will be deposited is extremely small, but it does not greatly diminish with depth.

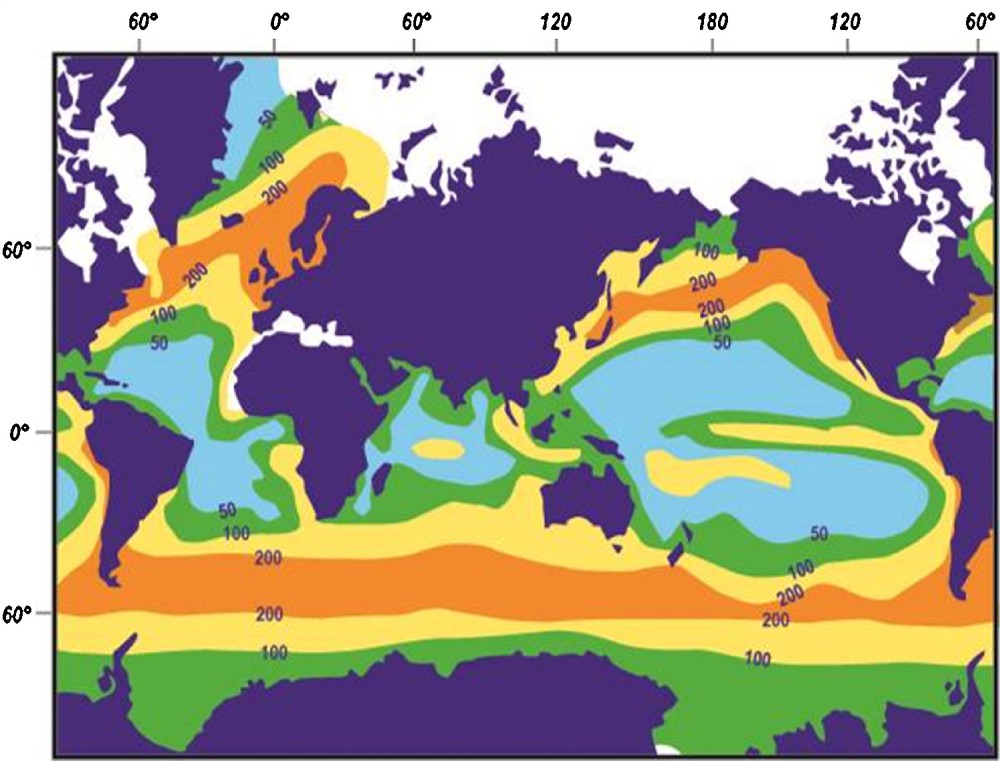

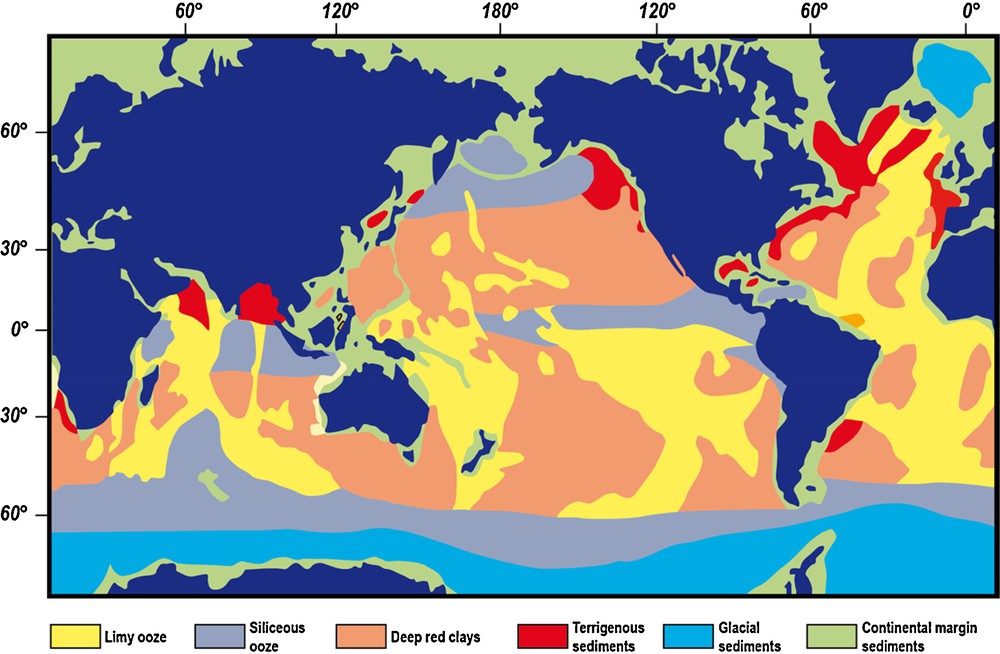

Comparison of the oceanic distribution of planktonic and deposited biogenic silica (Figs. 5 and 6) indicates that the zones of high phytoplankton productivity overlie sediments rich in siliceous debris. The most productive areas (300 mg Corg/m2/a) are upwelling zones such as some western margins of continents or monsoon-subjected oceans (Caulet et al., 1992; Diester-Haass et al., 1992; Sarnthein et al., 1992; Takahashi, 1986). The production of biogenic silica and of marine organic matter both result from a high plankton activity (De Wever and Baudin, 1996). They do not, however, always remain associated in the sediment. Quantitative estimates of the organic matter produced by living radiolarians are rare. Some data show, however, that it may be significant and even the main factor controlling the export of carbon to the deep ocean according to some authors (Lampitt et al., 2009, 2010). In fertile seas up to 1000 g/m3of radiolarian lipids and up to 2500 g/m3 of radiolarian organic matter (OM) can be conveyed to the surface water. That is to say 30 g of lipid/m2/day and 160 g OM/m2/day (De Wever et al., 2001). In the Benguela Upwelling System (W Africa), the radiolarian paleoproductivity correlates well with the organic carbon content and opal in the samples and all three parameters change in synchrony with the benthic isotope curve and are good proxies for paleoproductivity. Conversely, the carbonate does not correlate with the productivity indices, because it is interpreted to primarily reflect carbonate dissolution (Lazarus et al., 2008).

(Color online.) Annual production of biogenic silica by the plankton (chiefly diatom frustules and radiolarian skeletons), expressed in g/m2/yr of amorphous silica.

Adapted from Lisitzin, 1985.

(Color online.) Distribution of main types of sediments in recent bottom oceans.

Adapted from Davies and Gorsline, 1976.

A gross estimation based on Anderson's data (1983) reveals that radiolarian lipids in bottom sediments may represent from 15 to 50% of the total organic matter. With such a high oxygen requirement, demand can easily exceed supply, resulting in an anoxic environment. In most ooze, anoxia usually occurs when the volume of dispersed organic carbon exceeds 5%. This fits with more recent observations where organic sedimentation was associated with radiolarian development (Lampitt et al., 2009).

Today, it is widely accepted that the radiolarian-rich members of diatomites reflect cyclic increases in productivity related to seasonal upwelling activity, while the clay-rich members are the result of sporadic continental run-offs. Depositional patterns of Miocene diatomites are roughly of the same order as those of the laminated sediments recently deposited in the Santa Barbara Basin (California). The various lithological members of the Monterey Formation are, for example, comparable to the modern laminated sediments of the Santa Barbara Basin that are deposited at depths ranging from 300 to 1200 m, partially within a minimum oxygen zone (inducing a lack of bioturbation). The number and the thickness of the lithological cycles from the Tripoli formation (Sicily) vary following the geographical distribution of the analyzed series (39 to 34 cycles from the southern to the northern parts of the Caltanisetta Basin), but biostratigraphical studies have shown that the average duration of one cycle is of the precession order (as in modern coastal upwelling deposits). It is generally thought that the sporadic abundance of radiolarians with well-diversified assemblages is a reflection of increased paleoproductivity sometimes referred to as upwelling activity.

In summary, some clear differences exist between living radiolarians and the skeletons included in the sediments, but the main trends are the same: they are more numerous in zones of highest productivities due to upwellings. This fortunate situation allows the geologist to attempt reconstructions of the plankton distribution during the Mesozoic.

4 Contribution of radiolarians to pre-Cenozoic oceans

Radiolarites s.s. consist of beds of red or green cherts, measured in centimeters, alternating with shale beds, measured in millimeters. Radiolarites are of great importance for paleogeographical reconstructions, since their frequent association with ophiolites are used to date old oceanic crusts and to propose geodynamic models. They are good markers for reconstructing the evolution of ancient continental margins.

For a long time, radiolarites, most of which are red in color, have been compared to oceanic red clays (Lisitzin, 1971). It is now admitted that this comparison is incorrect and that the only common feature between these deposits is the color. Indeed, trace elements composition, clay mineral content, biogenous components, and geographical location of radiolarite and red clay deposits are different.

In many cases, epigeny helps to preserve radiolarian skeletons by replacing silica with calcite, pyrite, smectites, zeolites and, even, rhodochrosite, kutnahorite, and clinoptilolite, etc. (De Wever and Caby, 1981). Pyrite epigeny is commonly observed. When preserved in limestones, radiolarian debris is sometimes found in small “nests”. Often a sample containing a rich and diversified assemblage is adjacent to one that is almost void of any remains. Even etched parts of the same sample may vary in their radiolarian content. It is thought that these nests of pyritized radiolarians result from initial fecal pellet deposits. Fecal pellets are known to be reduced microenvironments that facilitate pyrite deposition (Fig. 7).

Pyrite epigeny of fecal pellets with radiolarians of Hauterivian age.

Courtesy P. Dumitrica.

The proximity of some of the radiolaritic formations to volcanic areas was emphasized in the early literature and a genetic association between radiolarian deposits and volcanism has been proposed by several geologists since Steinmann (1905). This simple and direct connection is merely a striking coincidence. Indeed, if this were the case, oceanic siliceous oozes should be preferentially located along mid-oceanic ridges, which they are not. It has been demonstrated that radiolarians are abundant in the modern ocean when nutrients are available.

4.1 Upwelling control

Radiolarites are common in the Mesozoic deposits folded within orogenic belts all over the world (Alps, Apennines, Taurus, Himalaya, Japan, and Rocky Mountains). Jurassic radiolarites are the most common and the best known of all radiolarites. The abundance of radiolarians preserved in Upper Jurassic radiolarites can be interpreted according to different hypotheses. A most convincing hypothesis infers large oceanic radiolarian blooms related to nutrient input as strong as those found in upwelling processes (De Wever et al., 1994). Such an interpretation is supported by the fact that radiolarians were probably the only marine planktonic organisms able to fix silica in the oceans at that time. Diatoms are well known from the Early Cretaceous and perhaps since the Early Jurassic period, but they only became abundant during the Late Cretaceous. The rapid accumulation of organic matter in bottom sediment may have resulted in anoxic conditions favoring the preservation of amorphous silica. Geochemical proxies of paleoproductivity (e.g., barium) also fluctuate in agreement with radiolarian concentrations. Bak (2007), for example, mentioned a link between the presence of radiolarians in sediments and upwelling circulation based on chemical analysis of Ba/Al and Ba/Sc in Cenomanian rocks of Poland.

Mesozoic radiolarites usually represent the first sedimentary layer overlying mid-oceanic basalt. Their depositional and diagenetic patterns can be diverse. Radiolarites are often composed of layers of cherts regularly alternating with intervals of siliceous shales, and are known as bedded cherts. These laminations may result from several processes (De Wever et al., 1994, 2001) such as:

- • diagenetic segregation of the silica from initially sub-homogeneous siliceous oozes;

- • episodes of successively high and low production of radiolarians during constant sedimentation of siliceous oceanic oozes;

- • episodes of increasing deposition of radiolarians caused by increased water circulation with a constant (or not) input of clay mineral particles;

- • episodes of high input of detrital material related to strong water circulation with the radiolarian sedimentation rate being constant. Evidence shows that in Cenozoic deposits in California (Monterey Formation) and Peru (Pisco Formation), silica diagenesis played a significant role in the formation of the bedded cherts resulting in an important loss of porosity and a reduction in the thickness of the siliceous deposits. During these post-depositional processes, silica-rich layers were enriched in silica, while shale beds were impoverished.

4.2 Seasonal control

Beds resulting from diagenesis appear to emphasize the pre-existing sedimentary discontinuity: i.e. the Tethyan radiolarian bedded cherts from Greece may have been a result of the astronomical variations in the rotation of the Earth that drove oceanic productivity (De Wever, 1987).

Some modern examples can help to understand past processes. An astronomical control was suggested for the accumulation of the Plio-Pleistocene deposits of the Owen Basin (Murray and Prell, 1992), and upwelling deposits off northwestern Africa (Shimmield, 1992). Sarnthein and Faugères (1993) also calculated a Milankovitch cyclicity for the variations in the manganese and biosilica contents of some laminated radiolarian-rich oozes off eastern Africa. These authors noted that the peaks in biosilica abundance correspond to a 23,000 years cycle and are correlated with upwelling activity, and, hence, the forcing process of the primary planktonic productivity is tied to orbital constraints. For Mesozoic times, Molinie and Ogg (1992) and Hori et al. (1993) provide evidence for an orbitally driven, periodical variation of accumulation rates as the origin of chert/claystone alternations in all the radiolaritic basins they analyzed.

Ribbon radiolarites do not, however, display the same alternation everywhere. For example, cyclic intervals are different in Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous radiolarites from the northern Apennines (Italy) and from Greece. According to Barrett (1982), the cyclicity of the bedded cherts is 2500 to 10,000 years in the northern Apennines, while it is 23,000 years in Greece (De Wever, 1987). Barrett (1982) showed that different sedimentological characteristics correspond to different cyclicities in both formations. The time discrepancy between the alternations calculated for the Italian and Greek radiolarites could mirror either various depositional patterns resulting from different palaeogeographic locations, as the radiolarites from Italy are closer to emerged lands and to the Tethyan cul-de-sac than the radiolarites from Greece, or different geographical positions. Such a difference is well known for Recent sediments in the Atlantic Ocean where the climatic control (three main Milankovitch frequency bands) on sedimentation largely depends on the latitudinal location of the sediment cores (Bout-Roumazeilles et al., 1997). The 100,000-year signal occurs as a uniformly acting factor, whereas the 41,000-year signal dominates clay sedimentation at high latitudes and the 23,000-year signal dominates at mid-latitudes. The authors suggest that the latitudinal variations of the orbital forcing on sediments in the North Atlantic Ocean not only result from climatic control (temperatures), but also from latitudinal control (winds, currents).

4.3 Depth control

There are many discussions in the literature about the conditions of deposition of radiolarites. For a long time it was thought that these siliceous sediments accumulated in large deep oceanic basins (> 3000 m) enriched in silica by volcanism along spreading ridges. We know, today, that the deposition of old siliceous sediments was not necessarily characteristic of deep environments and nearby volcanism. The biosiliceous deposits that might be modern equivalents of radiolarites are found in different oceanic environments. They are located in shallow coastal basins such as the Santa Barbara Basin (California), in depressions of the continental slopes (Guaymas, Sonora, Baja California, Mexico), on continental margins (Callao and Pisco, Peru), and in shallow and deep oceanic basins (Owen Basin, northwestern Indian Ocean, and central Indian Ocean Basin). Laminated deposits are never found at great depths (500–600 m in the Santa Barbara basin, 300–1300 m in the Guaymas Basin, and 300–800 m in the northwestern Indian Ocean). Non-laminated biosiliceous sediments accumulate at all depths. The fossil-bearing siliceous sediments ultimately transformed into radiolarites were thought to be initially devoid of calcareous components and it was, thus, supposed that they were deposited under the calcium carbonate compensation depth (CCD). Today there are, however, some indications that the Mesozoic siliceous deposits may contain some calcareous components and that the corresponding CCD was probably shallower than it is in the modern ocean (Kastner, 1981).

Many Tethyan radiolarites and bedded cherts were deposited on subsided continental margins (Figs. 1 and 3), where the depositional environment was significantly shallower than in true oceanic realms. These shallow environments were located in coastal basins of the same order of magnitude as those where the Monterey and the Messinian diatomites accumulated, or in more oceanic basins, such as the Owen Basin. Mesozoic Tethyan radiolarite basins were elongate, narrow, relatively small, and locally restricted, with deposition occurring sporadically. These Mesozoic basins were probably open to the ocean from which they were only partly separated by submarine topographic highs.

Comparing the Mesozoic Tethyan basins with the modern basins from the northwestern Indian Ocean (Fig. 3) is of interest for several reasons. All are, or were:

- • submitted to significant bottom water currents;

- • located at similar latitudes on the northwestern edge of an ocean;

- • blanketed by biosiliceous sediments.

The geographical distribution of these basins on the eastern side of the Gondwana continent was not favorable to the development of important upwelling systems related to boundary currents. However, as is true today, monsoon activity, related to a similar distribution of the continental and oceanic masses, may have induced seasonal upwelling activity that increased the surface water productivity and the accumulation of radiolarian oozes on the oceanic floor (De Wever et al., 1994). The bedded cherts in the Tamba and Chichibu Belts of Southwest Japan have also been interpreted as resulting from a high primary productivity due to upwelling patterns (Suzuki et al., 1998).

4.4 Monsoonal control

4.4.1 General characteristics

The monsoon is a major wind system that reverses direction seasonally leading to large-scale sea breezes. They typically blow from cold to warm regions, from sea toward land in the summer because in the summer sun heats the land faster than the ocean water, and conversely from land toward sea in the winter. Most summer monsoons have a dominant westerly component and a strong tendency to ascend and produce copious amounts of rain (condensation of water vapor in the rising air). Winter monsoons have a dominant easterly component and a strong tendency to diverge, subside, and cause drought.

The major monsoon systems of the world consist of the Asian–Australian monsoons and (West) African, North and South American monsoons. In southern Asia, the spring and summer heating of the Tibetan Plateau causes the air above to rise, creating a low-pressure region that draws in moisture-laden air from the adjacent oceans. The resulting winds rising over the southern slopes of the Himalayas bring heavy rains to swell the rivers. Strengthening of the Asian monsoon has been linked to the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau after the collision of India and Asia around 50 million years ago (Fluteau, 2013; Fluteau et al., 1999). Many geologists believe that monsoon first became strong around 8 million years ago based on records from the Arabian Sea and the record of wind-blown dust in the Loess Plateau of China. However, it is now understood that in the geological past, monsoon systems must have always accompanied the formation of supercontinents such as Pangaea, with their extreme continental climates (Fluteau, 2013).

4.4.2 Monsoon in the Mesozoic Tethys

Based on different kinds of arguments (sedimentological, geochemical, paleontological, etc.), since the 1990s (Parrish, 1993) monsoons are suggested to have influenced Pangea. More recently, several authors suggest that monsoons have influenced the whole Tethyan realm (i.e. Preto et al., 2010). Among these places some are known for Triassic radiolarites in holosedimentary piles, i.e. Lagonegro Basin (Bertinelli et al., 2005; De Wever and Miconnet, 1985; De Wever et al., 1990; Martini et al., 1989), or associated with basalt in the Meliata Basin (De Wever, 1984; Ozsvárt and Kovács, 2012) as detailed by Rigo et al. (2012). Beside pelagic rocks, Triassic platform carbonates have been interpreted in relation to seasonality and hence monsoonal climate (Mutti and Weissert, 1995).

Some younger sediments also have a deep imprint of monsoons in the western Tethyan realm (Raucsik and Varga, 2008; Raucsik et al., 2001; Sucheras-Marx et al., 2013) during Early Jurassic and even in the northwest where Tethys is closing, during Middle to Late Jurassic times as in the French Subalpine Basin (Giraud, 2009).

Recently a review of Tethyan radiolarites (Baumgartner, 2013) admitted a possible monsoonal origin for some central Tethyan deposits such as those of Hawasina, Pichakun, and Kermanshah, but preferred to suppose the influence of river input to explain the high productivity. The Caribbean River Plume Model was inferred for the Middle and Late Jurassic (Baumgartner, 2013). Radiolarite deposition in the area lasted for much longer, from the Middle Triassic to the Late Cretaceous (Fig. 1). Favorable nutrient-rich conditions thus persisted, although considerable changes in climate and consequently continental runoff occurred during this long period of time. We argue that monsoonal upwelling, as a long-term phenomenon, could be the predominant mechanism to maintain high surface productivity during practically the whole Mesozoic.

It is now widely accepted that monsoons existed over the Tethyan region during most of the Mesozoic. Monsoons are due to the juxtaposition of a landmass and water-mass in a latitudinal position (current examples are Texas north of the Gulf of Mexico, Sierra Leone north of the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, Australia, Bangladesh north of the Gulf of Bengal).

During the Jurassic, a landmass in the north was latitudinally separated from the Tethyan Ocean, in the south by a very long boundary: more than 12,000 km while the longest nowadays is around 3000 km at the most (Fig. 8). Therefore, strong monsoons were active in northwestern Tethys, and the seasonal changes were able to trigger upwelling currents in the western part of the Tethys Ocean similar to the Indian monsoon that presently leads to seasonal upwelling in the Somalia and Owen basins. This cyclical organization explains the alternation of chert with shales and/or pelagic carbonate (De Wever, 1987).

(Color online.) Relative position of landmasses and oceanic waters allowing, or not, monsoon activities.

These monsoons were very active when the Tethyan Ocean was widely open, during most of Mesozoic times. Significantly, productive waters provided sediments with a lot of silica (as it is the case today off Peru; Suess et al., 1988). In these places, the high planktonic productivity is connected to strong upwelling currents. In present-day oceans, abundance of siliceous organisms is not known along oceanic rifts, neither in sediment nor in plankton. However, abundant siliceous remains are found where strong upwelling currents are active, such as off Peru, where sediments rich in radiolarians and diatoms exist on the platform, in waters no deeper than a few hundred meters (100–200 m) (De Wever et al., 1995). In such places, the productivity is so high that waters are acidified, and consequently the CCD is very shallow. Its depth is at only few tens of meters on the external platform off Peru (i.e. 150 m for site ODP 681, Suess et al., 1988; De Wever et al., 1995, 2001).

When the Indian continent was crossing the Tethyan region monsoons were much less active or even not active, and not productive enough to have siliceous sedimentation. Some 40 millions of years ago, the Indian continent collided with Eurasia and provided a new opportunity for monsoons to be active (Fig. 8).

5 Conclusions

The Mesozoic radiolaritic facies has been considered as a deep facies for almost a century because of its close relationship with pillow basalts. However, no other argument was able to support this hypothesis except, perhaps, the scarcity of associated limestone. For most of Mesozoic times, the paleogeography of the western Tethys offered the conditions for a strong monsoonal activity that fit with sedimentological (high silica content, facies, bedding, setting) and paleontological (timing, taxa) elements.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried as a contribution of the team UMR 7207 CR2P “Centre de recherche sur la paléobiodiverité et les paléoenvironnements” of the “Muséum national d’histoire naturelle”, Paris, and visits of two authors at the Muséum during years 2010–2013. We thank Sylvie Bourquin and Vincent Courtillot for their reviews, and Elspeth Urquhart for improving the English.