1. Introduction

Earthquakes and earthquake swarms are commonplace in many parts of the world, including on various islands. Mayotte island was an exception to this before May 2018, when inhabitants experienced hundreds of earthquakes within a period of two months, including the largest recorded earthquake on May 15, 2018, which was a 5.9 on the Richter scale. These earthquakes, whose epicenters are located about 50 km east of Mayotte [Bertil et al. 2021], were felt throughout the island. While structural damage to buildings did occur [see Sira et al. 2018], fortunately no major catastrophic destruction happened. Nevertheless, the earthquake swarm incited panic and distress among the local population, to the point that governmental entities set-up hotlines for psychological support. Considering this unprecedented swarm, people were beside themselves, with many leaving their homes to wait out the night under the open air. From afar, these reactions could appear exaggerated, but it is important to understand what happened from the point of view of those living through the earthquakes. Mayotte is not safe from natural disasters, such that studying how people experienced this unpredictable and disturbing event may help future awareness-raising efforts. Storytelling can provide various types of insight into such occasions, such as revealing awareness, reaction, and language regarding earthquakes, the latter of which is particularly pertinent in contexts with complex, multilingual landscapes. The goal of this study is to provide a modest linguistic analysis of 36 short narratives as told by Maore (inhabitants of Mayotte) who faced the earthquake swarm. It is written for non-specialists to provide a small lexicography and corpus of the language used to describe the events surrounding the earthquakes, and this in the two dominant local languages of the island—Shimaore and Kibushi. It seeks to answer the question of how language is used in short narratives.

2. Literature review

2.1. Considering language, storytelling, and earthquakes in disaster communication

Researchers in many disciplines across the globe have looked at the intersection of natural disasters, narratives1 and language. Language can be studied from various approaches, be it issues of translation, evaluation or creative expression for healing. First, considering narratives, people around the globe encounter natural disasters, including earthquakes and people, no matter their background, tell stories as a way to share their experiences. After harrowing events such as earthquakes, people sometimes tell stories to help understand the disasters [Iida 2016; Parr 2015], to work on identity construction [Delante 2019; McKinnon et al. 2016] and to share their experiences with others [Childs et al. 2017; Wu 2014]. Linguistic expression has proven to be an important research avenue, and some have explored the use of poetry to express survival and trauma, for example with the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 [Iida 2016, 2020] or with the typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines [Parr 2015]. Short texts such as tweets can be analyzed to understand how emotion is expressed, such as signaling fear and anxiety during the Great East Japan Earthquake [Vo and Collier 2013]. Large-scale projects exist that solicit narratives for various purposes, such as the UC QuakeBox Project, which collected oral histories surrounding the 2011 Christchurch earthquake [Clark et al. 2016]. Storytelling in seen as a way to heal after destructive earthquakes such as the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake [Wu 2014; Xu 2013]. Indeed, stories can help individuals make sense of disasters and they provide insight into the role of belief systems and religion [Abbott and White 2019].

Besides aspects of identity and affect, earthquake stories are studied in order to understand their structure such as linguistic markers and coherence in narratives [Luebs 1992], the use of reported speech in earthquake narratives [Gawne and Hildebrandt 2020], or other broad language documentation questions [Hildebrandt et al. 2019]. This is particularly interesting considering the fact that narrative structures vary according to language, even among bilingual speakers [Pavlenko 2008, 2014]. That is, language use and form are important factors for understanding how individuals react to and process natural disasters.

Narratives exist en masse as well in the media and government discourses surrounding disasters, and they are known to (re)construct disasters and the collective memory via language. Some studies look at larger socio-political constructions of a shared narrative, such as how political leaders discuss natural disasters to help their political agenda [Windsor et al. 2015]. Media coverage of natural disasters provide a rich area for understanding how journalists (re)create history, engage in narrative, and play with affect during coverage. For example, narratives from inhabitants have been used in the Indonesian media to discuss earthquakes in ways that demonstrate biases in event coverage [Irawanto 2018]. In addition, reflecting on distant earthquakes via narratives is a way for media to shape collective memory and reconstruct the past, as could be seen with the 1999 “921” earthquake in Taiwan [Su 2012].

Beyond narratives, communication during and after disasters—particularly with government bodies—can be limited and inefficient, even when a common language is shared [Hong et al. 2018]. As seen in many disasters, multilingualism in a population can complicate information dissemination. Language minority speakers and immigrants who do not have their language represented in the media or in governmental communication face particular barriers during earthquakes, whether in receiving information or communicating in the aftermath. Such is the case for Mayotte, where there is no written media coverage in Shimaore or Kibushi. For television and radio, there is news coverage in Shimaore but not Kibushi, and most happens in French. This even though a sizeable percentage of the population does not understand nor speak the language [Insee Mayotte Infos 2014; Insee 2007].

Studies have highlighted the need to better understand local language difficulties in order to address risk management in societies. For example, earthquake relief efforts were met with problems regarding language with local Tibetan varieties in China during a 2010 earthquake, since media coverage and governmental aide was mainly in Chinese [Chunying and Shujun 2015]. Similar observations have been observed with immigrants and minority language speakers affected by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake [Kawasaki et al. 2018; Shinya 2019] and the 2011 Christchurch earthquake [Shinya 2019]. People in these regions faced real-time issues with understanding risk, such as evacuation procedures and recovery-related services. Lack of multilingual resources concerning natural disasters remain a concern. Recent studies push for the need for bilingual resources concerning risk with earthquakes, such as with Spanish and English in the U.S. [Bravo et al. 2019]. Be it in the moment or in the aftermath, communication issues related to multilingualism needs to be addressed.

There are many ways and reasons to look at how natural disasters are discussed by people in the aftermath of an event such as an earthquake. Discourse, particularly narratives, provide insight into how experiences are lived, perceived, and assessed in retrospect. Storytelling can be found across cultures and is an easy way to solicit lived experiences and crises. This study focuses on how Maore recount the earthquake swarm, including the language they use and how they evaluate reactions in the stories. The purpose of this study is to understand how speakers used Shimaore and Kibushi when talking about the events. Specifically, it looks at language use in the context of the narratives themselves, considering the overall structure, including the main events, and any evaluative or emotional aspects found within. There is little to no research on how Maore express themselves in Shimaore and Kibushi regarding earthquakes. This is a problem considering recent efforts to bring awareness to risk concerning natural disasters on the island, including those related to earthquakes. This article offers a modest contribution to understanding how Maore talk about earthquakes, to gleam insight into lexical and grammatical considerations, including questions of shared language, formulaic language [Wray 2002], and lexical bundles [Biber et al. 2004].

2.2. Mayotte in context of the earthquake swarm

It is beyond the scope of this article to give an exhaustive look into Mayotte, its rich history, and its diverse population. For robust insight into the island culture and languages, see Blanchy [1988], Lambek [2018], Martin [2010], Rombi [1984] and Walker [2019]. In order to contextualize the earthquake stories, I provide as much insight as needed regarding Mayotte during the earthquake swarms in 2018 and the narrative recordings in 2019, including background information on the geological, linguistic and cultural characteristics of the island. First, inhabitants in Mayotte rarely experience earthquakes nor do they have an earthquake-related culture, unlike in other regions of the world such as countries located on the Pacific Ring of Fire (Japan, Chile, U.S. to name a few). Before 2018, the largest recorded earthquake occurred in 1993 and was a magnitude 5.2 on the Richter scale, located about 30–40 km west of the island [Bertil et al. 2021, “Essaim de séismes” 2019]. Small tremors may be felt occasionally, but there is no precedent in the collective memory of Mayotte that could compare to the earthquake swarm that started in May 2018. To summarize, Maore are not accustomed to earthquakes.

Because of this, one can imagine the reaction when over several months, islanders felt hundreds of earthquakes, with the largest ever recorded embedded within that time period. People were panicked, and news coverage of that period show worried villagers gathering outside at night to seek safety. Governmental entities and the scientific community were also taken aback by the events and were unprepared to respond with clear explanations for the phenomenon. In fact, it took about a year to discover that volcanic activity off the coast of Mayotte was the source of the swarm. While fortunately no major damage or direct deaths occurred, the population was under stress and indirect injury most likely did occur. Besides distress, this unprecedented event evoked confusion, as again people did not understand the origins of the swarm of earthquakes. One reaction observed in media coverage involved soliciting a higher power for protection and mercy. Some inhabitants believed the earthquakes were God’s punishment for indecent behavior [Fallou et al. 2020]. Indeed, the vast majority of inhabitants in Mayotte practice a Sunni Shafi’i Islam [Blanchy 1988; Lambek 2018; Philip-Gay 2018; Rombi 1984]. Calls to prayer are heard five times a day from multiple mosques in villages, with even the smallest village of only a few hundred habitants having a mosque (such as Mbouini). Due to its proximity to the equator, the time of the call to prayers is relatively stable, with the first, Fajr, occurring between 4:00 and 5:00 am. Islam as a belief and practice can be seen in various aspects of island life, such as the fact that children often attend religious schools (shioni or madras) in addition to secular French public schools. Finally, it should be noted that Ramadan started on May 17, 2018, which is a month of daytime fasting and religious reflection. Just before the earthquake, Mayotte had undergone months of social and economic distress with roadblocks and the closing of various services, including the university center, due to insecurity and immobility.

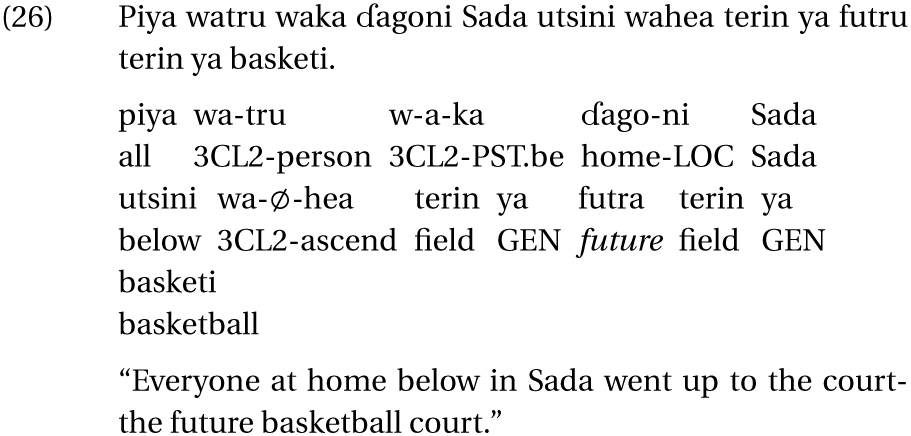

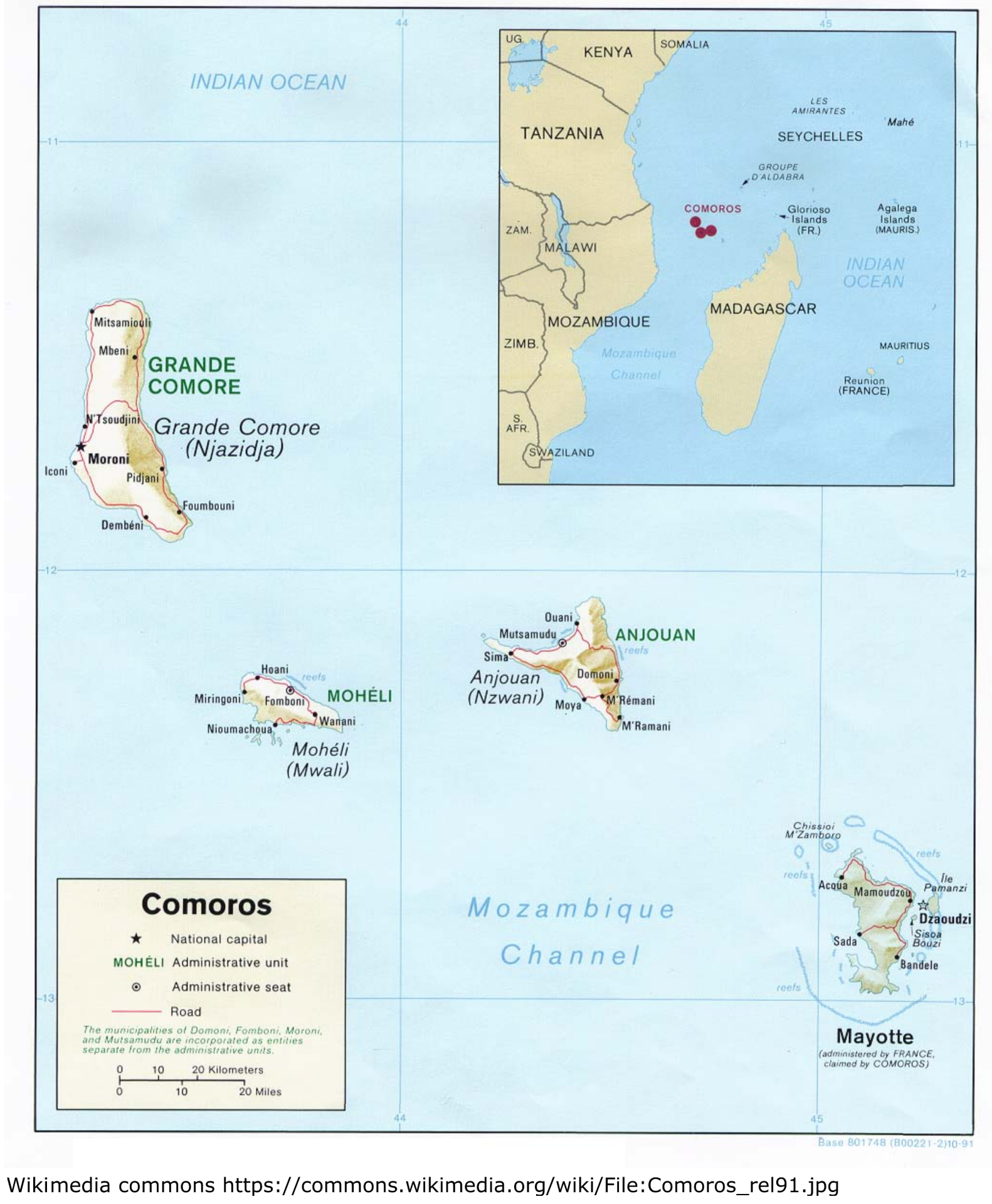

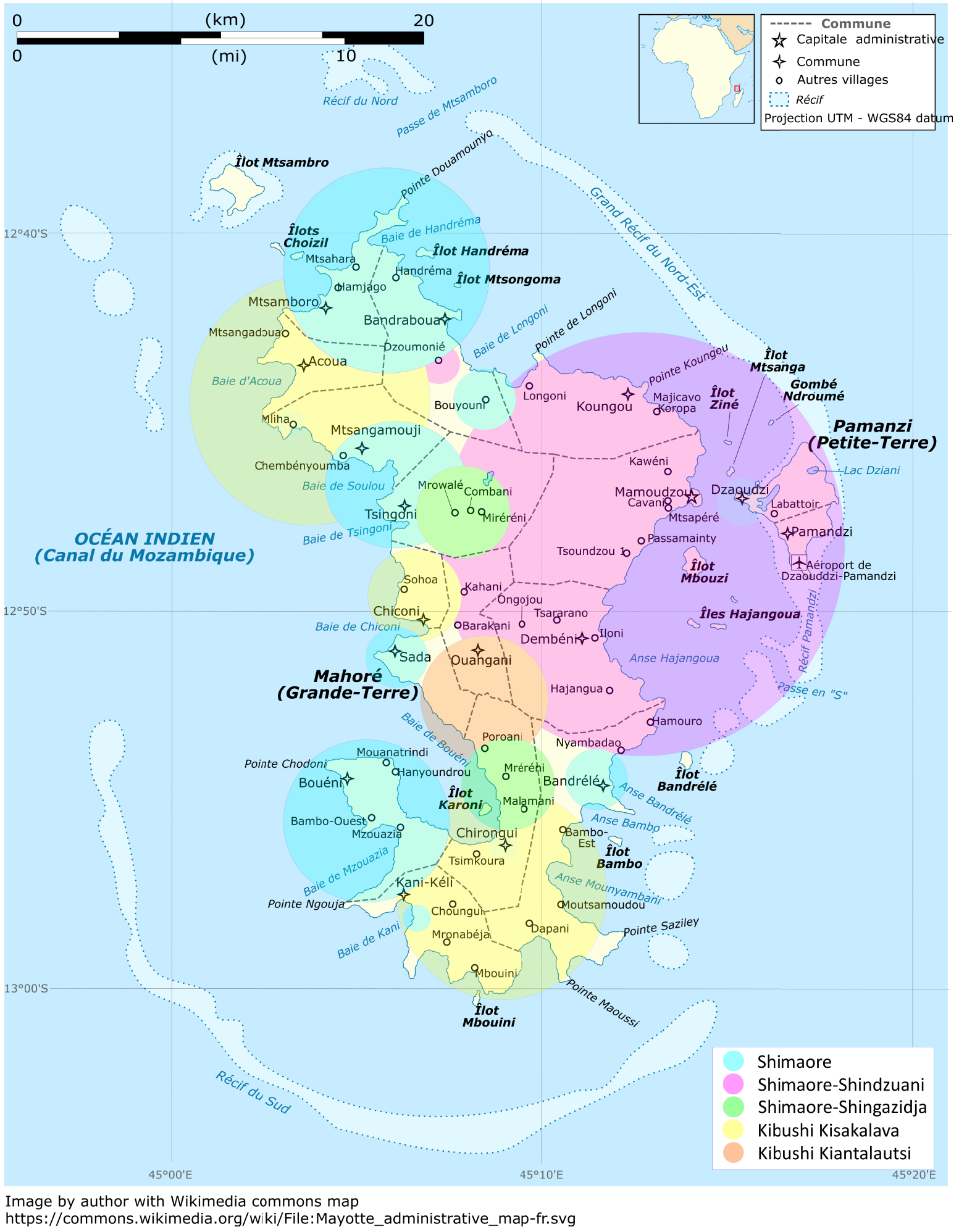

There are two main local languages spoken in Mayotte. The first is a Sabaki Bantu language, Shimaore, (Guthrie classification G44d) [Nurse and Hinnebusch 1993; Patin et al. 2019] spoken by roughly 80% of inhabitants. There are various varieties of the Bantu language spoken here, but there are two which are the most predominant and which are mutually intelligible: Shimaore (from Mayotte) and Shindzuani (from Anjouan), the presence of the latter due to a high influx of immigration from the neighboring island of Anjouan, located only 65 miles northwest of Mayotte, as seen in Figure 1. Considering birth and immigration statistics [Insee 2021], an increasing number of Bantu speaking inhabitants speak a Shindzuani variety. Estimates suggest 41% of the habitants speak Shimaore and 31% speak a variety of the three Comorian dialects Shingazidja, Shimwali and Shindzuani [Insee Mayotte Infos 2014], with the latter dialect representing a large proportion. Given the demographic situation (such as mixed families, contact in neighborhoods and schools), these two varieties are in contact and are probably undergoing various changes because of it.

Map of the Comorian Archipelago in the Mozambique Channel.

Nevertheless, in everyday discourse, people use the term Shimaore to indicate the Bantu language variety spoken on the island in comparison with Kibushi, the Austronesian language spoken by about 15% of islanders [Jamet 2016]. Kibushi itself has two varieties, Kisalakava, the most common and Kiantalautsi, a variety spoken only by a few thousand inhabitants in two villages: Poroani and Ouangani. The Bantu and Austronesian languages spoken in Mayotte are not mutually intelligible, even if there are shared words such as for “thank you” (marahaba), “each” (kula), or “really” (swafi), which are terms arguably borrowed from Shimaore. Figure 2 shows a rough estimate of language varieties spoken in Mayotte. As seen, Kibushi is present in parts of the West and South of the island, whereas Shimaore and Shindzuani are spoken in villages all over the island. Some villages have a mix of Kibushi and Shimaore such as M’tsangamouji or Ouangani. Dense urban areas on the northeast part of the island such as Mamoudzou, prove to be complex in terms of variation and language contact, such that identifying them just as influenced from Shindzuani can be limiting.

Approximate distribution of the local languages and their varieties in Mayotte.

3. Methods

3.1. Setting

The short stories were collected at the Centre universitaire de formation et de recherche (CUFR) of Mayotte during a larger sociolinguistic study concerning the local languages carried out between March and November 2019. Participants were recorded in a soundproof booth to avoid recording noise issues often encountered on the field.

3.2. Participants

As for participants, 36 individuals, of which nine men, partook in the study, who were for the most part local university students and personnel. Participant age ranged from 22 to 49 years of age, with most being women in their early 20s. Except for one participant, I know all the individuals personally, having worked with them or taught them for months or years. Among participants, 28 were bilingual French–Shimaore speakers and eight were French–Kibushi speakers. Recordings were done in Shimaore and Kibushi, and discussion with participants in French. Besides language, other demographic information varied such as income, village of residency, as well as family history with Mayotte. Participants lived in villages throughout Mayotte, such that one region or village was not representative. Some participants came from families having lived for generations in Mayotte, while others were first generation immigrants from Anjouan, often with modest living conditions. Because of this, the “Shimaore” speakers in the study spoke either a Shimaore with little influence from Shindzuani or a variety heavily based on Shindzuani. Due to the voluntary nature of the study, gender, language, and age are not representative.

3.3. Procedure

As discussed in Section 3.1, these stories come from a larger study, which used sociolinguistic interview methods to elicit various types of data [Schilling 2013]. First, the participant and I discussed in French the earthquake swarm experienced the year before, and we talked about the fact that on at least a couple nights, many villagers left their homes to be in an open space. All participants recalled these events and were eager to discuss with me. Next, I expressed my desire to hear them describe their experiences in Shimaore or Kibushi and asked them to imagine that they were discussing these events with a friend or family member who was not in Mayotte when the earthquake swarm occurred. One reason I did this was to record participants paying little attention to their speech, as they are concentrating on telling a story charged with emotion, what Labov calls the “danger of death” story type [Labov 1972]. The other reason was to better understand how some Maore lived through the earthquake crisis, since I knew it was a harrowing experience for some. After the storytelling, we discussed again the events and I have remained in contact with some of them. Recordings varied from 30 s to 7 min, with an average duration of 2.5 min.

3.4. Analyses

Recordings were transcribed and translated by bilingual French–Shimaore and French–Kibushi speakers. Transcriptions and translations were then analyzed to look at morphology and to facilitate refined translations and glossing using FieldWorks 9.0 [``Fieldworks'', 2020]. For Section 4.1, stories were thematically analyzed using RQDA [Huang 2012] for chronotopic features, including deixis of time, space, and person. Orthography of the languages aligned with suggestions made by the Association Shime [2016] and the Conseil Départemental de Mayotte [2020] in that the orthography is as transparent as possible, privileging IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) symbols for phonemes. Various lexical resources were used including the dictionaries from Blanchy [1996], Gueunier [2016], and Jamet [2016], the latter two being for Kibushi. The dissertations of Blanchy [1988], Johansen Alnet [2009] and Rombi [1984] on Shimaore were also consulted, as well as Ahmed-Chamanga’s [2017] text on the grammar of Shindzuani. Standard Leipzig glossing rules are used in examples 1–50 [“The Leipzig Glossing Rules,” 2015]. Glossing is included for eventual insight into the structure of the language for non-linguists. The intention is to have a small contribution to understanding theses languages, particularly because no written grammar exists for either one.

4. Results

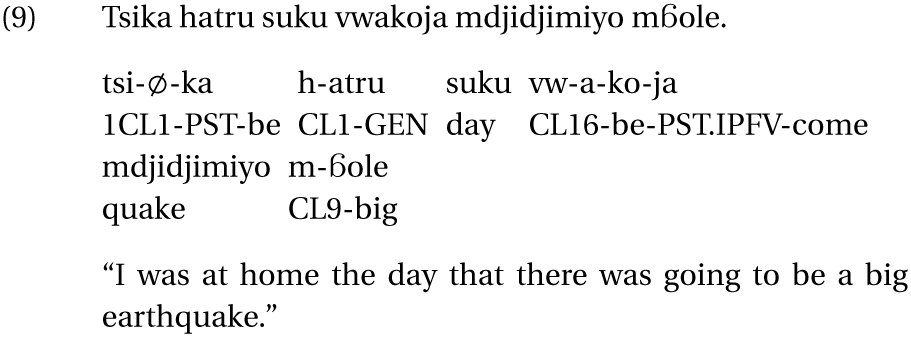

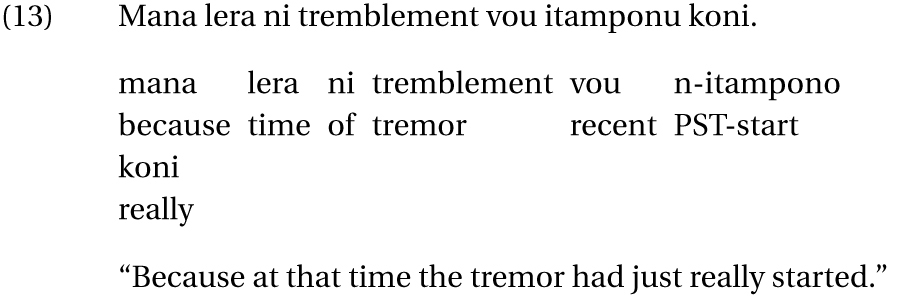

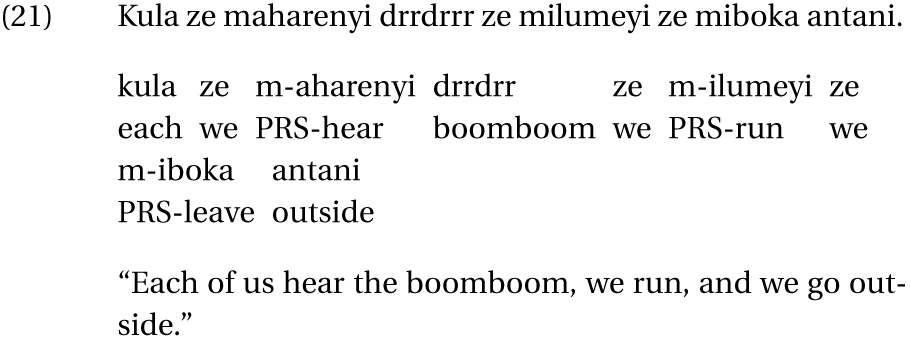

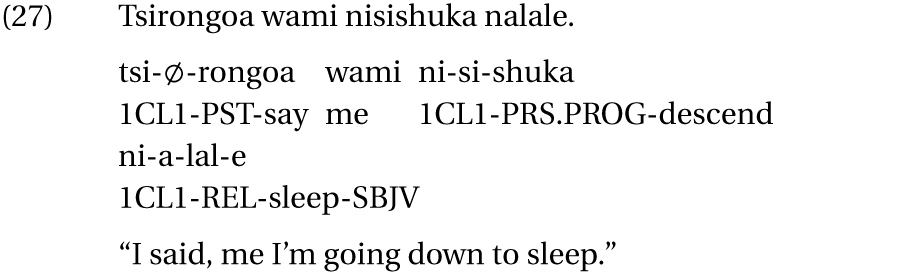

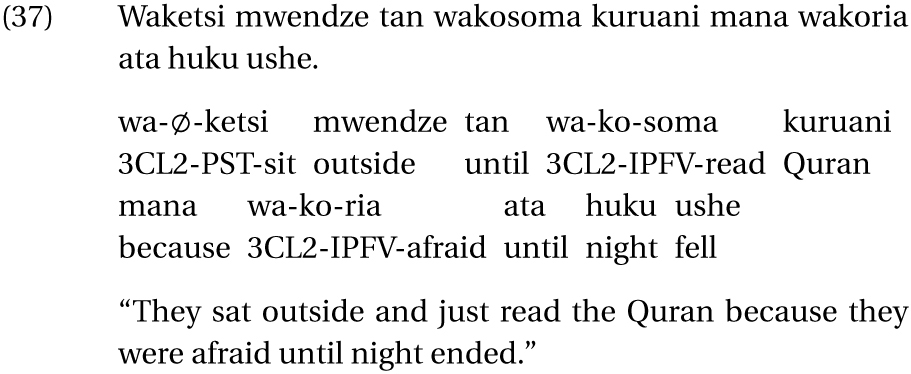

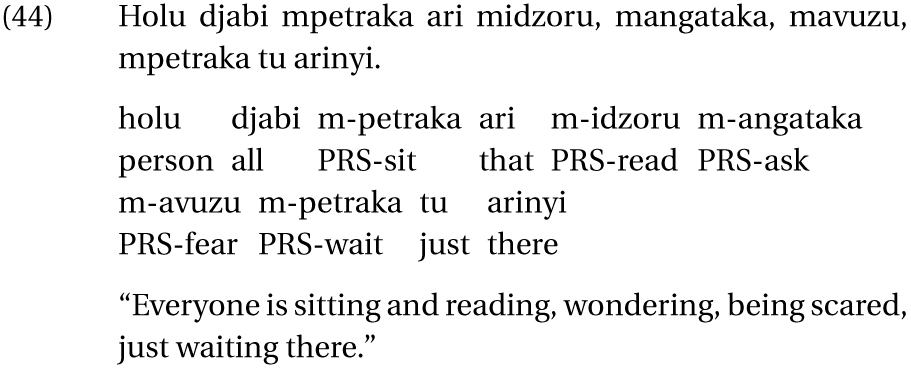

4.1. Overall story structure via chronotope

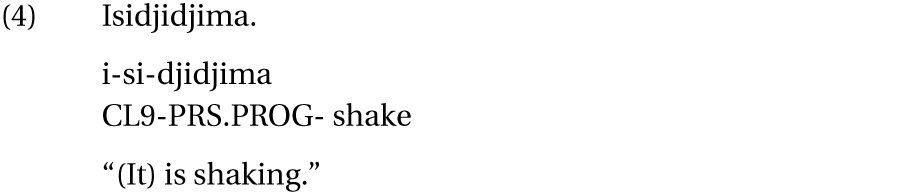

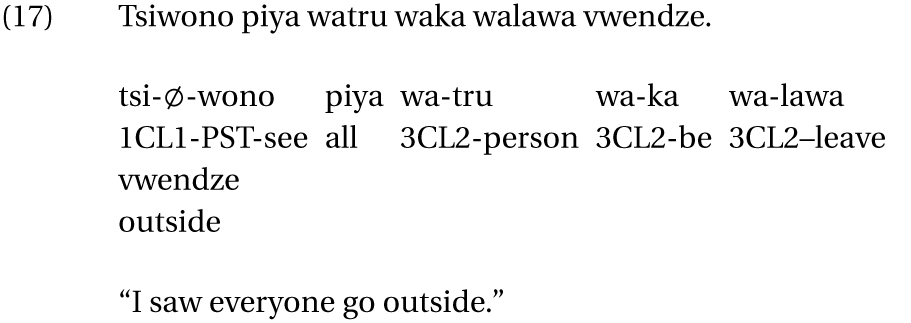

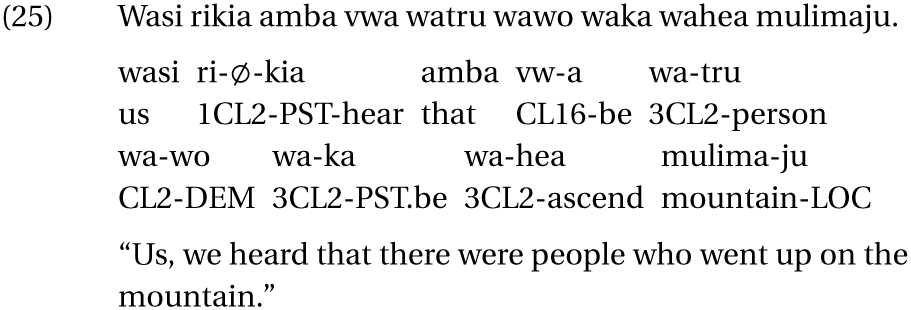

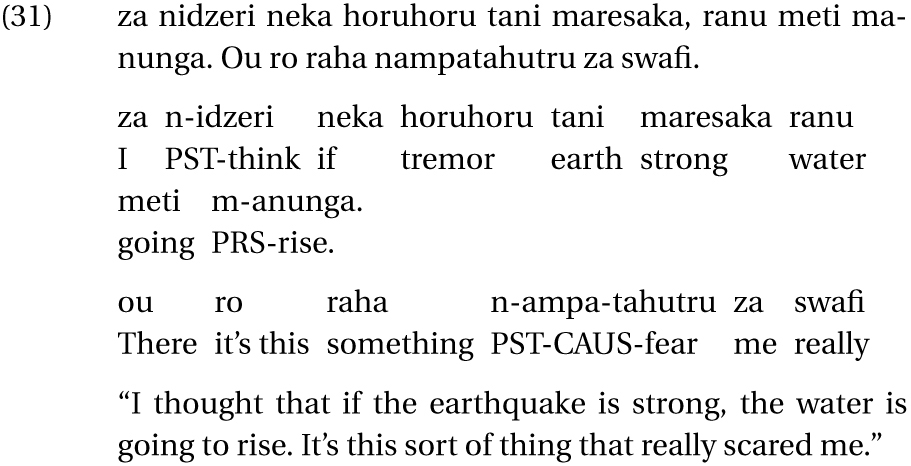

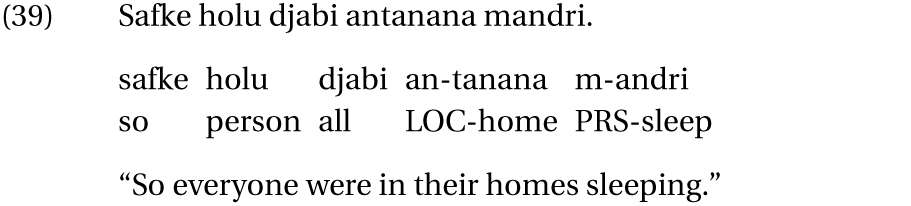

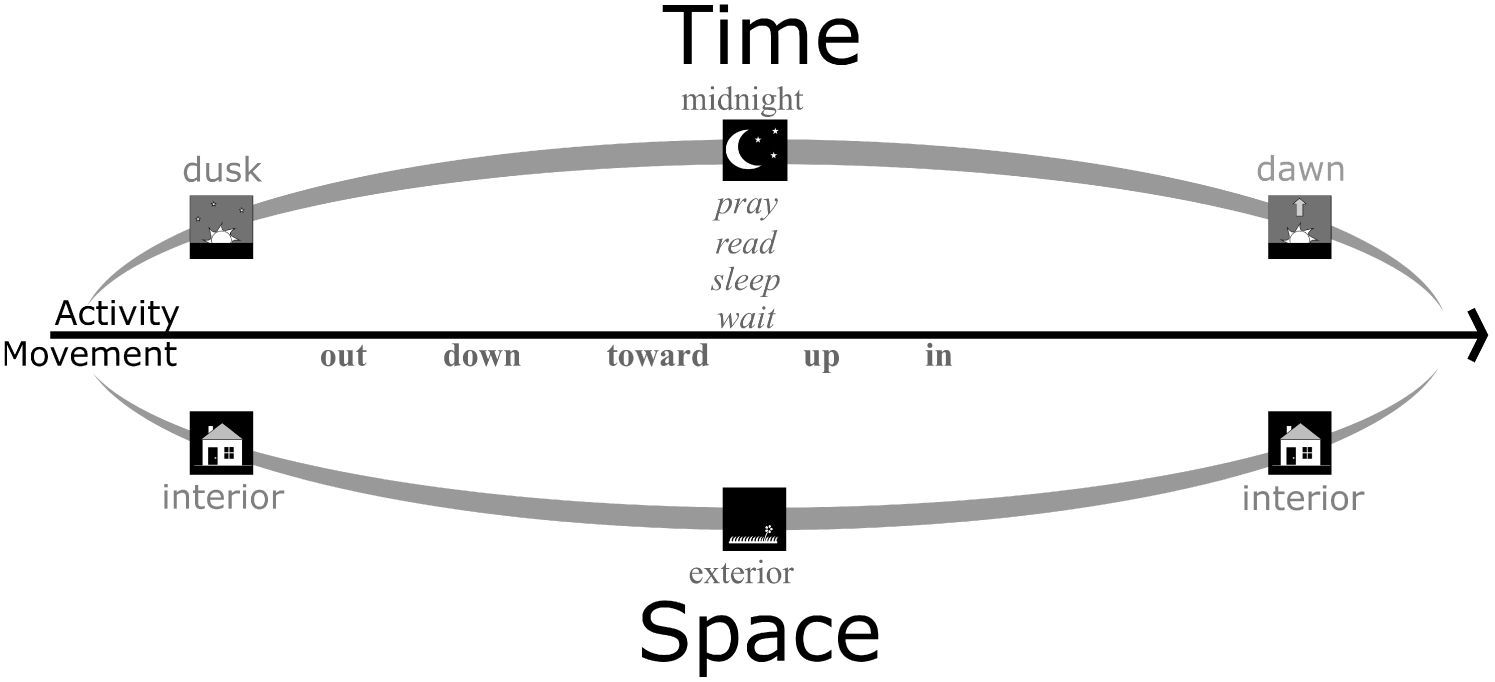

Before describing various linguistic aspects of the narratives, a brief description of the overall patterns for the narratives and the organization of the stories along the time and space axis is provided. This is because the language analyzed in the studies is closely linked to the overall narrative structure and thus it is important to describe it. For an in-depth narrative analyses, see Mori [2021]. Most stories begin with individuals inside their houses. They start with an orientating action [Labov and Waletzky 1967] in a certain time and space envelope, also known as chronotope [Silverstein 2005]. In this study, the time and space envelope is night in Maore villages during the earthquake swarm and is represented in Figure 3 [from Mori 2021]. This figure shows the chronotope in which the stories develop. Read from left to right, a “there-and-back again” pattern can be observed, in which people start inside their homes in the earlier part of the night before leaving to an open area, only to return indoors near dawn. Various activities can be observed during the time spent outside.

Diagram of the time and space envelope (chronotope) for the earthquake stories.

The complicating action occurs with storytellers either waking up to an earthquake or receiving an urgent notice that they must immediately leave the house to find shelter in an open area or to pray for mercy. These notifications come in various forms such as from a relative in the house (10 occurrences), a neighbor (3), a phone call (13) or a text message (6). Most storytellers describe deciding to go outside as requested, and they move toward parking lots, courtyards, soccer fields or in front of mosques. As for why they leave their homes, storytellers talk about the fact that a large earthquake (15) or a wave (3) was going to arrive. Others are motivated by the fear of falling debris (14) or because they need to invoke God’s mercy through prayer (10), this latter being potentially linked to why people gathered around mosques, as they are seen as a point of refuge.

Once outside, storytellers describe how people, in mass, engage in various activities but principally read holy texts (21 occurrences) and prayed (21). Some read the news or social networks on their phones (6), and some talk (5) while others wait (6) or sleep (6). In addition, some stories describe seeing individuals heading up to higher grounds to take refuge from an earthquake or rising waters. Many stories are resolved with individuals returning to their houses at dawn (14) or when overcome by fatigue (8). The resolution is the return home, to the inside of a building, and some include a coda in which they summarize the story events. Only two stories include the storyteller staying inside their house and refusing to join the others outside.

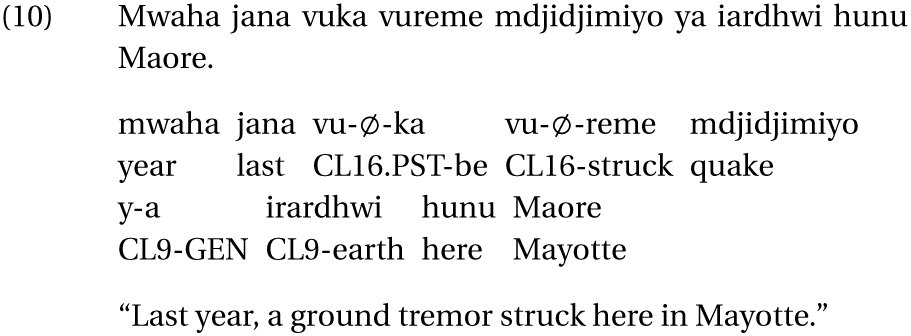

4.2. Language used to describe earthquakes

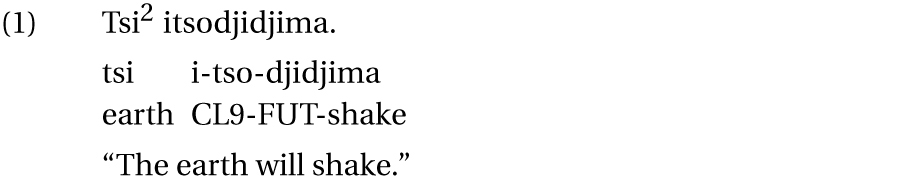

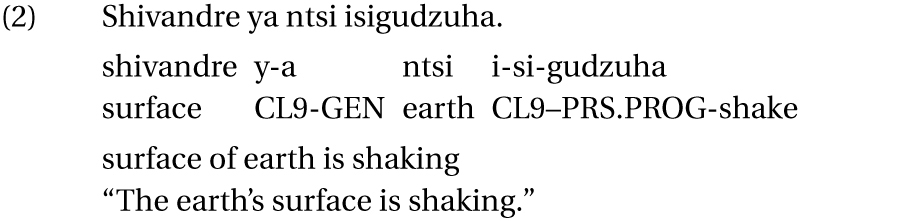

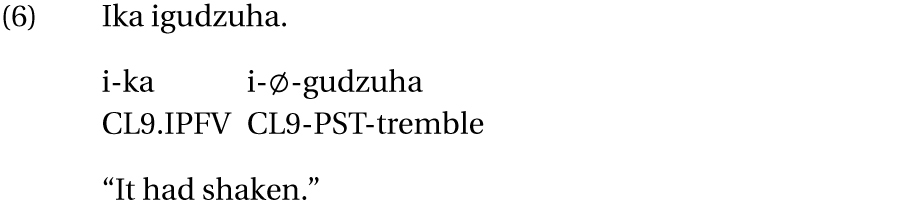

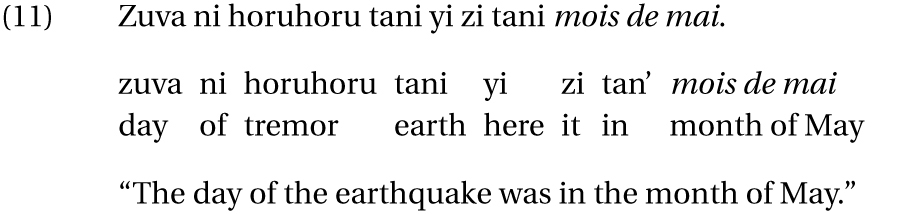

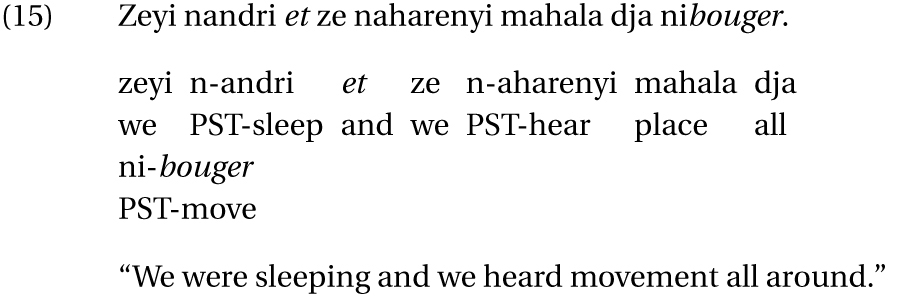

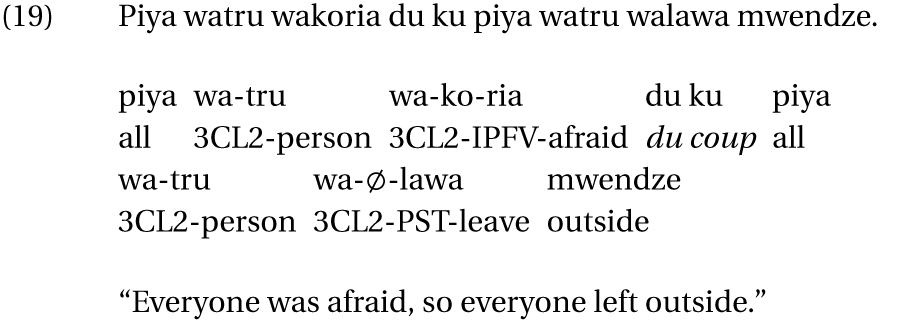

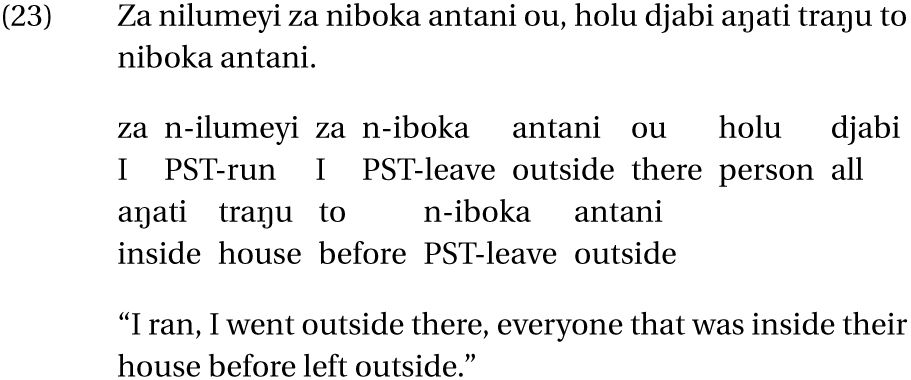

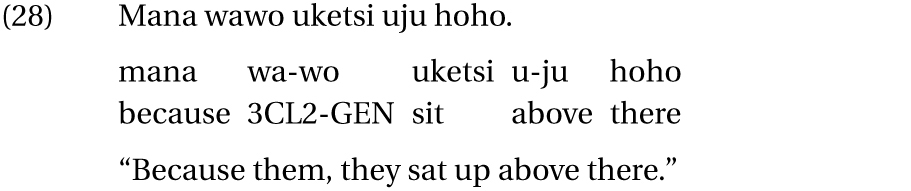

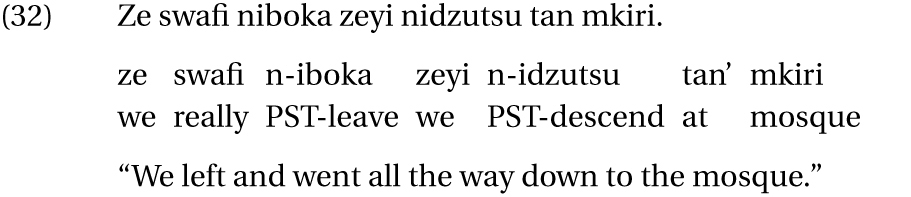

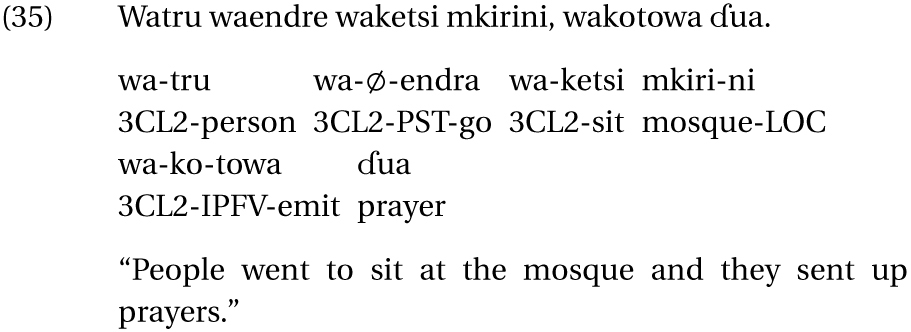

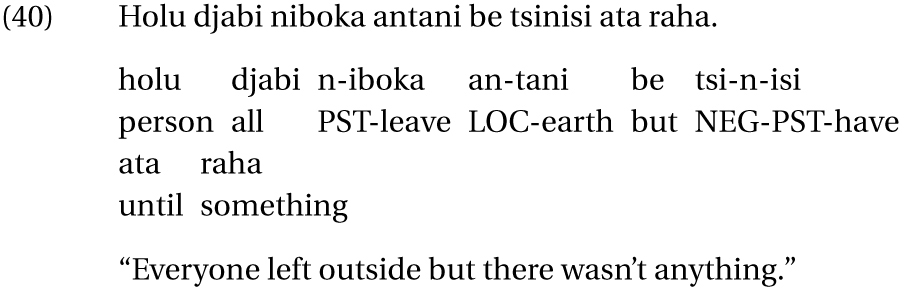

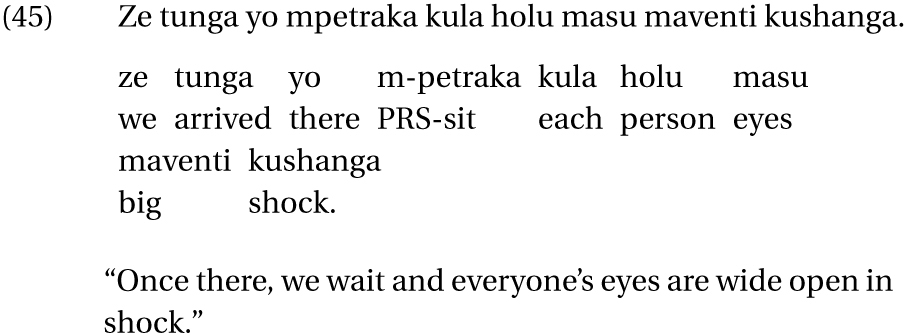

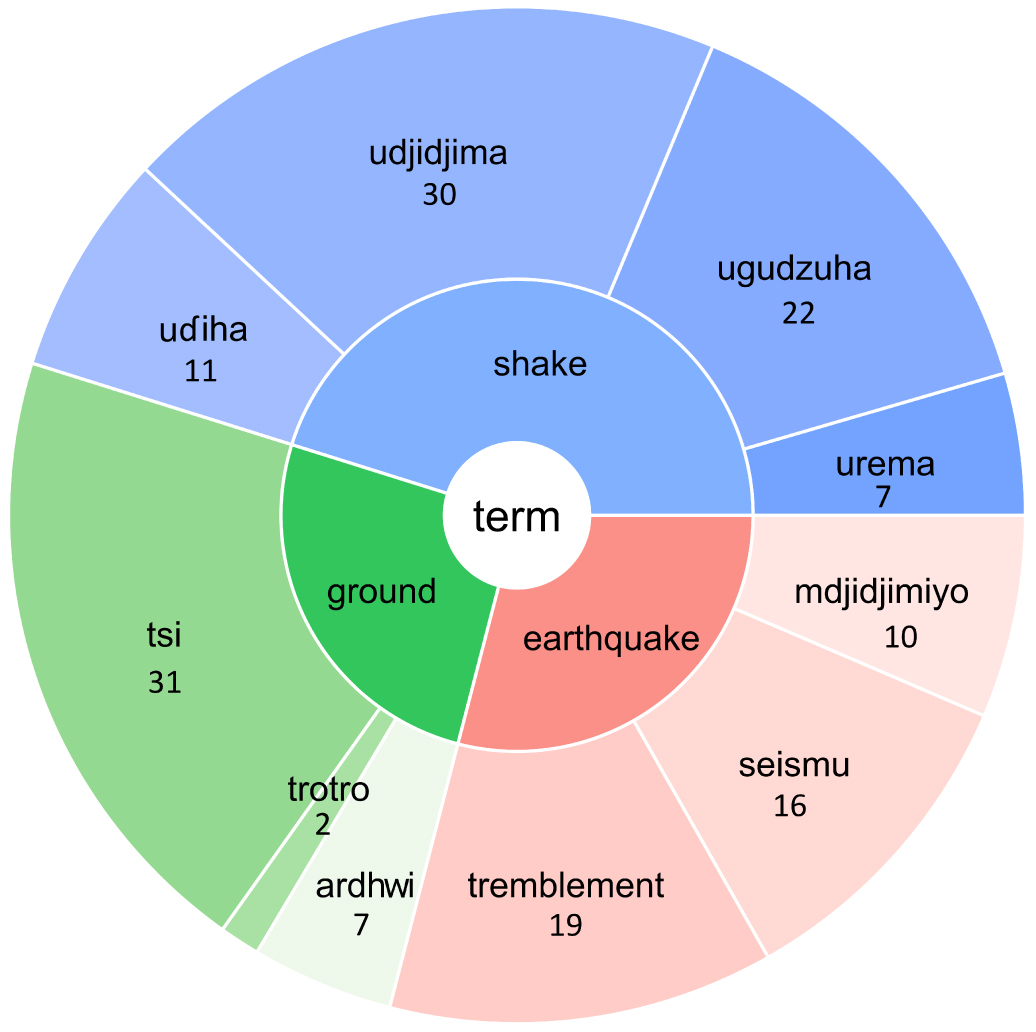

As seen in Section 4.1, the stories often start with discussion about an incoming earthquake or an earthquake being felt. Storytellers use one of two ways to describe the earth shaking. For one, they employ a noun meaning “earthquake” or simply “quake”, such as mdjidjimiyo (Shimaore, from now on Sh). The other way to discuss this phenomenon is through describing the earth’s movement in a phrase, such as mana tani mihetsiki (Kibushi, from now on Ki), “because the earth moves.” In these phrases, a noun describes the earth or the ground and a verb describing some sort of movement meaning to shake or tremble. To facilitate discussion, the two languages are from now on considered separately. First, for Shimaore, the most common way to describe the event was to use a phrase with the word ntsi or tsi (earth or ground) as the subject followed by a conjugated form of udjidjima (to shake), as seen in Figure 4. Examples 1 and 2 (Sh) show these verbs in use. See the Appendix for the interlinear abbreviations from the Leipzig Glossing Rules, such as CL9 = the nominal class 9 and FUT = the future tense marker, as seen in Example 1. i- marks the nominal class 9 and -tso- indicates the future tense.

Earthquake-related terms in Shimaore and their frequency.

The noun phrase shivandre ya tsi (the surface of the earth/land/ground) was common in the stories told in Shimaore. Other words to discuss the earth or the ground are trotro and ardhwi, the latter derived from Arabic, as seen in Figure 4. Verbs besides udjidjima are used in the stories to describe the movement of the earth shaking; this includes ugudzua and uɗiha. These verbs, while synonyms, have slightly different meanings. Udjidjima means to tremble or shiver, whereas ugudzua is closer to the verbs shake, shift, or stir [Blanchy 1996]. Uɗiha is an intransitive verb and similar to shift or move but can also mean to reanimate [Blanchy 1996]. Sometimes people used the word urema (to hit or strike) when talking about a seismu (earthquake) occurring, thus expressing the notion that an earthquake can strike. These verbs were conjugated into various tenses and aspects, including simple future, present progressive, present simple and past imperfect, as seen in 3 through 7.

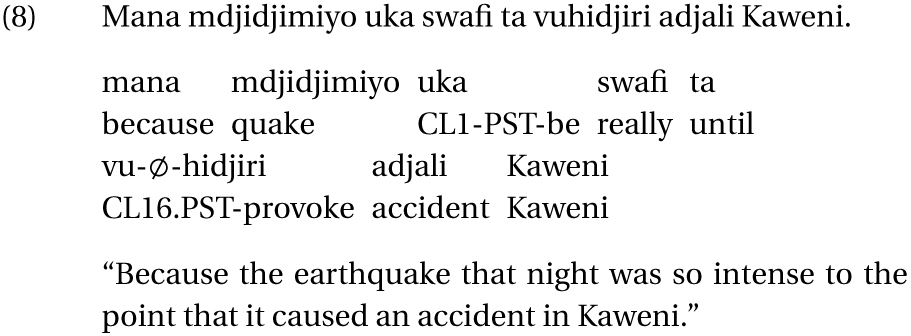

Regarding noun forms for discussing the earthquakes, speakers used nouns borrowed from French: tremblement (tremor) and seismu (earthquake) (see Figure 4). There were occurrences of one nominalized form, mdjidjimiyo, derived from the verb udjidjima (to tremble). This nominalized word means tremor or quake. The prefix m- is the nominal prefix and in combination with the suffix -iyo (or -io), creates an abstract noun form [Ahmed-Chamanga 2017]. This latter suffix is similar to the suffixes -tion and -sion in English. Examples 8–10 show how the noun forms are used. As we see, it is used to describe an entity that existed (8) and that can be modified, such as being described as “big” (9) (mɓole) and “of the earth” (10) (ya iardhwi). This use is not unlike ways of describing the phenomenon in English (an earthquake) or French (un tremblement de terre).

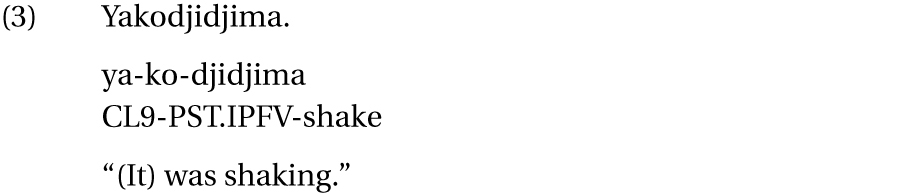

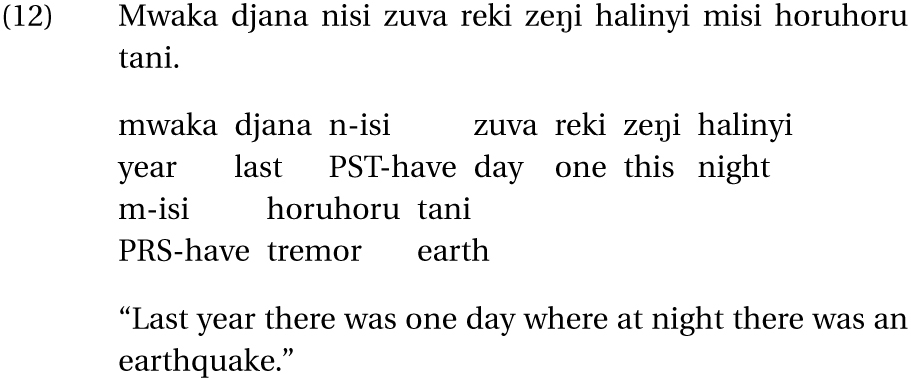

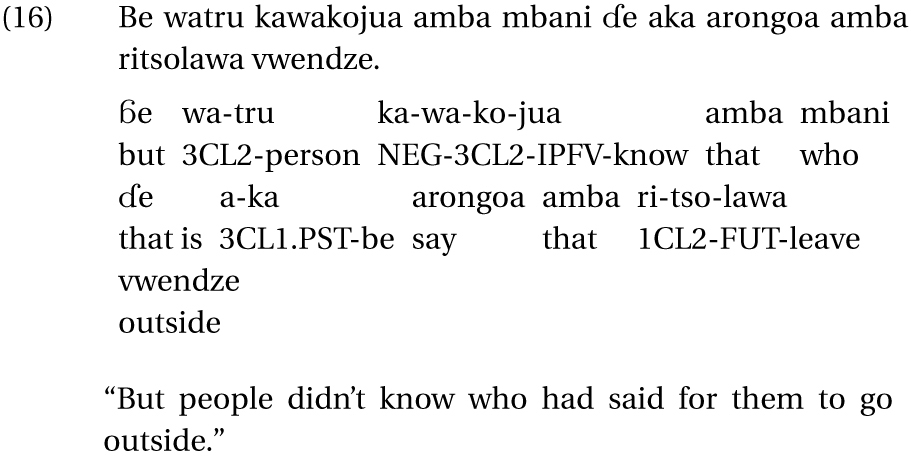

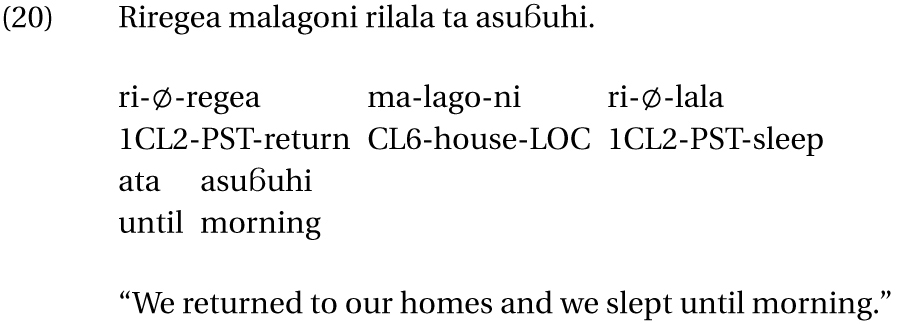

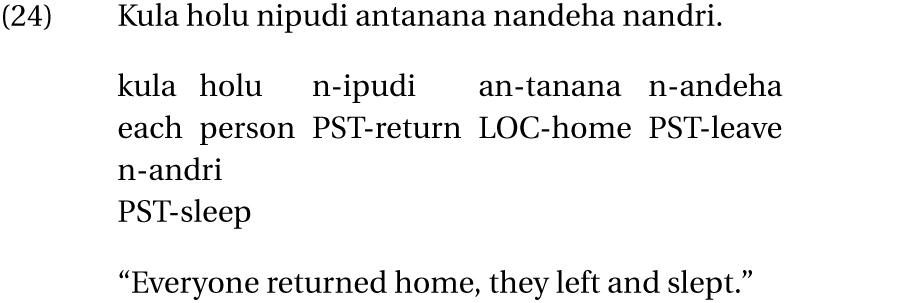

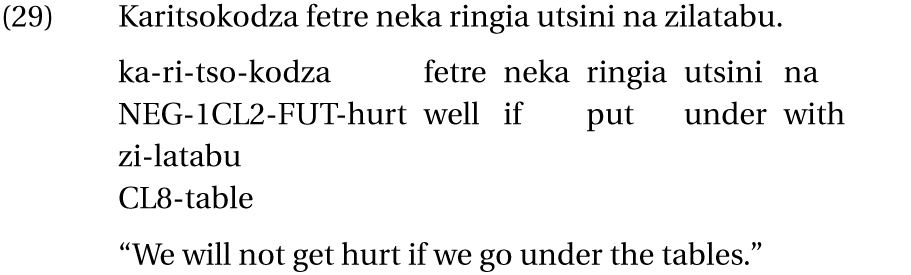

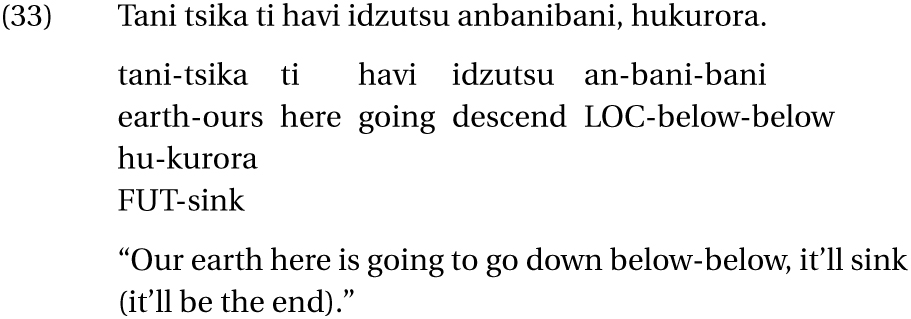

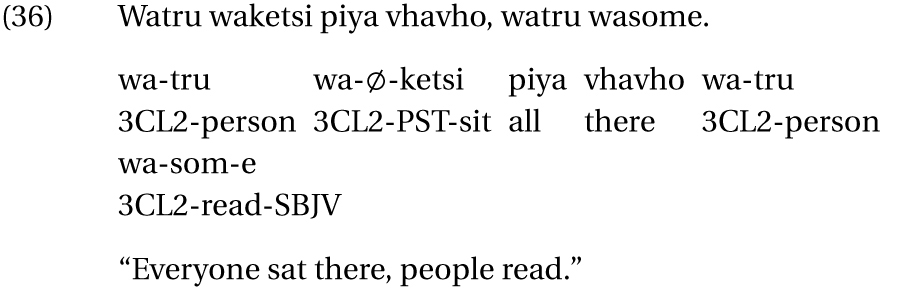

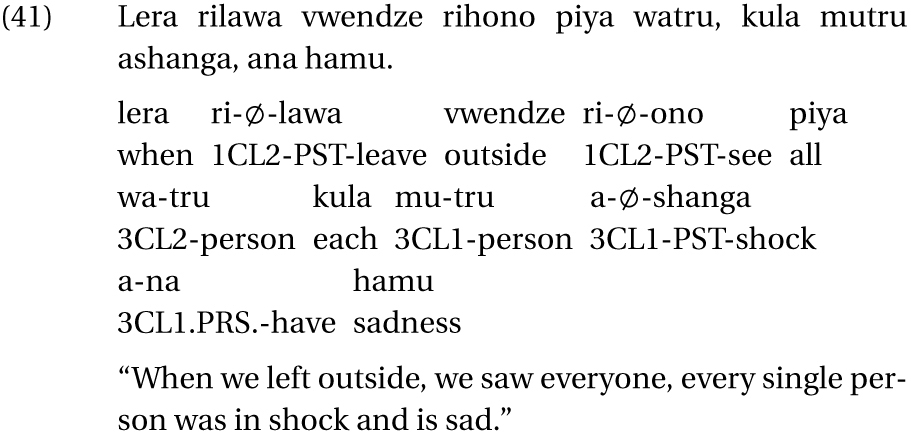

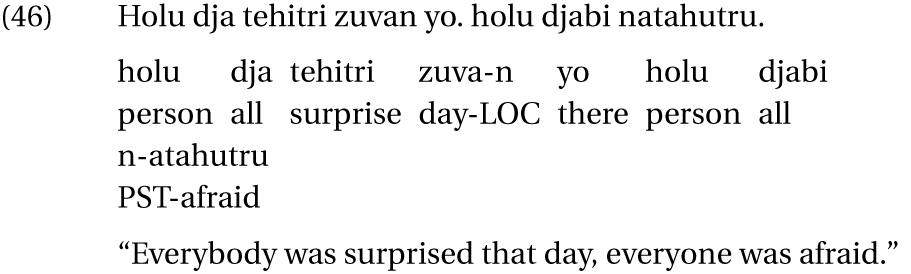

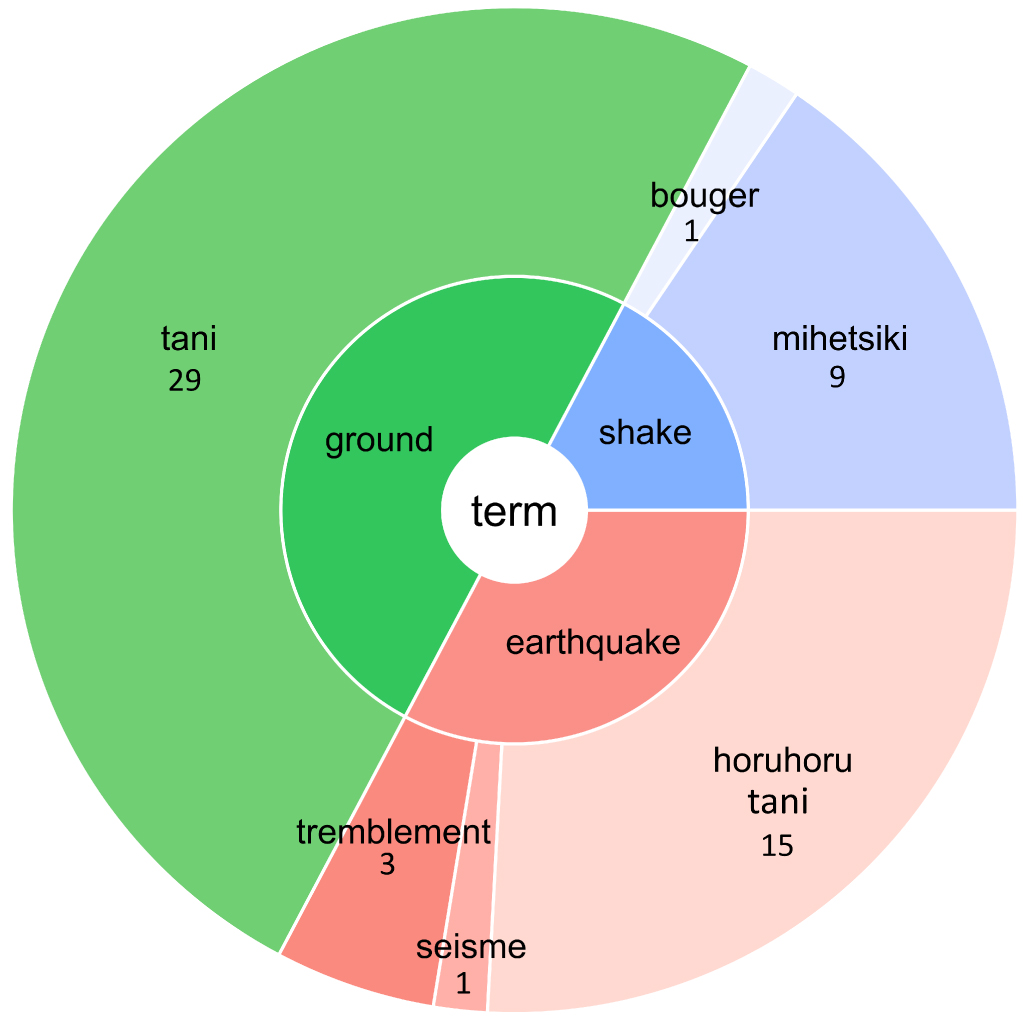

As for Kibushi, there was much less variation in the way the phenomenon was expressed, as seen in Figure 5. This may be due to sample size, or this may reflect stable terminology in this language. Nevertheless, in the stories told in Kibushi, speakers used the noun phrase horuhoru tani (earthquake), horuhoru meaning a tremor and tani meaning the earth, as seen in examples 11 and 12. Like the stories in Shimaore, there are instances of the French words tremblement and seisme (example 13). Furthermore, as seen in examples 14 and 15, some storytellers also used verb phrases, using the verb mihetsiki (shake) and once, bouger, borrowed from the French verb “to move” or “to shift”. As seen, the term used for the earth or ground is unequivocally tani.

Earthquake-related terms in Kibushi and their frequency.

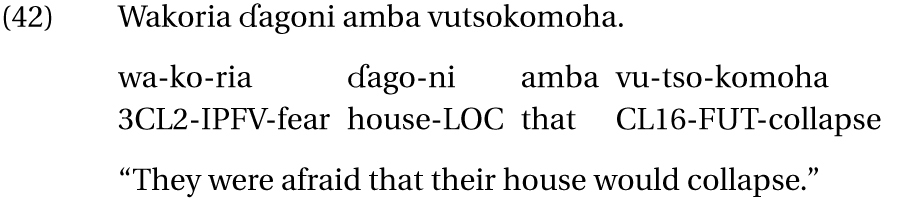

When comparing how the shaking of the earth is described in the two languages, we notice a difference in terms of nominalization. Kibushi has an established, transparent term (noun) for “earthquake” with horuhoru tani (quake earth), which is similar to the compound noun in English (earthquake) and the noun phrase in French (tremblement de terre). However, seeing that French loanwords nouns are used more often than mdjidjimiyo, Shimaore does not have an established, widely used nominalized form, though this may change over time with the increasing occurrences of earthquakes and heightened media and governmental attention. In addition, though not used by any participant in this data, there is an expression for describing earthquakes nyombe ya uzima, which means “zebu” (nyombe) “down below” (uzimu). This expression is known by many, with some stressing that it is an old, playful way of describing earthquakes, where it is said that the ground shaking comes from an underground “zebu” (an African humped cattle) moving its tail or ear. It is unclear why this expression was not used by any participant in this study, but it may be due to the young age of respondents. The only noun form used in Shimaore was mdjidjimiyo.

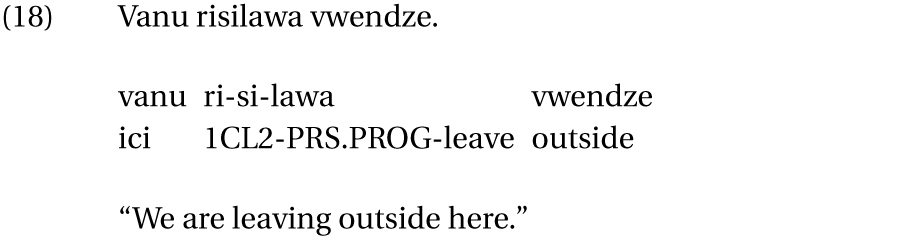

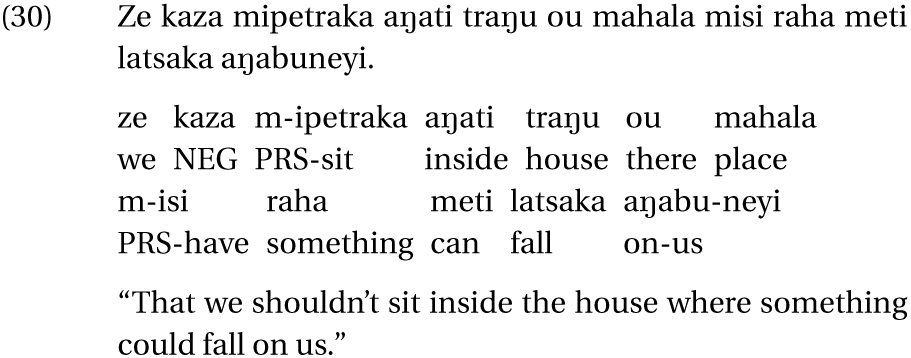

4.3. Language for describing movement and space

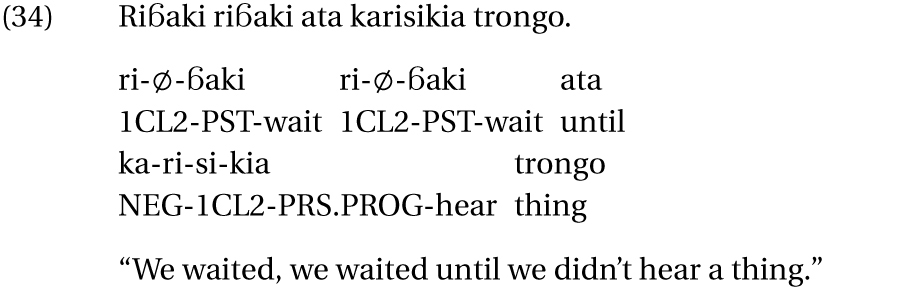

As discussed in Section 4.1, movement and position in space and time are an important element of these stories. The “there and back again” structure provides insight into how movement and position can be described in Shimaore and Kibushi. Table 1 shows frequent words (verbs, prepositions, and adverbs) used for discussing movement, activity, and position. A principal observation is that movement, activity, and position are similar regardless of the language. Spatial language is frequently employed, as storytellers orient themselves in the village once outside. Examples 16–24 show how these terms for space and location are used in the stories.

Terms for movement, position, and activity while outdoors in Shimaore and Kibushi

| Space | English | Shimaore | Frequency | Kibushi | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Movement | Leave | ulawa | 142 | miboka | 26 |

| Movement | Return | uregea (urudi) | 9 (4) | mipudi | 2 |

| Movement | Ascend | uhea | 14 | manunga | 3 |

| Movement | Descend | ushuka | 21 | midzutsu | 4 |

| Position | Above | uju | 11 | ||

| Position | Below | (h)utsini | 11 | anbani | 2 |

| Position | Outside | vwendze (mwendze) | 78 (31) | antani | 11 |

| Position | Inside | aŋati∗ | 8 | ||

| Activity | Sit | uksetsi | 82 | mipetraka | 23 |

| Activity | Sleep | ulala | 63 | mandri | 9 |

| Activity | Wait | uɓaki | 21 | miambinyi | 1 |

| Activity | Pray | ufanya/utoa ɗua | 16 | mikuswali | 2 |

| Activity | Read | usoma | 50 | midzoru | 6 |

| Activity | Discuss | uhadisi | 12 |

∗For phonetic transparency, [ŋ] is used. Jamet [2016] uses the grapheme “n̈” for this sound.

4.3.1. Shimaore

4.3.2. Kibushi

We see a nearly formulaic phrase for the act of leaving the house, which is a key moment in the stories. The subject is often either the first-person plural (we) or third person plural (they) and the verbs are often conjugated in the past tense. The adverb to describe outside, vhendze (Sh), mwendze (Sh) or antani (Ki) follows the verb. Other verbs to express movement in space are used, as participants move up or down in the village as a group and eventually return to their houses near dawn or when overcome with fatigue, as seen in examples 25–33. As seen, movement and location in space and time are important in these stories, as certain places become indexed with danger, such as home interiors.

4.3.3. Shimaore

4.3.4. Kibushi

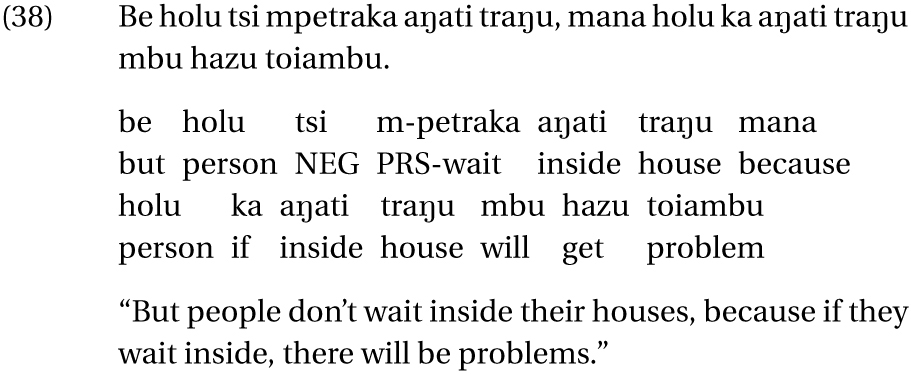

Finally, as discussed in Section 4.1, once outside, several activities are described, the most prominent being waiting, reading, and sleeping. These activities were discussed as happening in mass, with the subject pronouns in first or third person. In this context, reading refers to reading of holy texts (the Quran, certain chapters like the Yassine) and prayers. Most stories describe people staying up and waiting, but some also talk about sleeping outside on the ground or on mattresses brought outside. To give context to the words in Table 1 regarding action verbs that occurred while outside, examples 34–40 are provided below. Once again activities are described as happening collectively, with subjects being in plural form “we” or “they.” The examples also reveal motivations for some activities such as in 37 and 38 or they made connections between two actions, such as in 34 and 40.

4.3.5. Shimaore

4.3.6. Kibushi

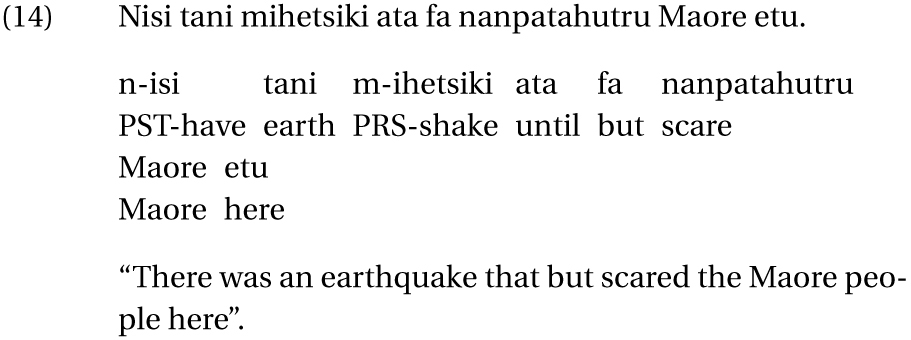

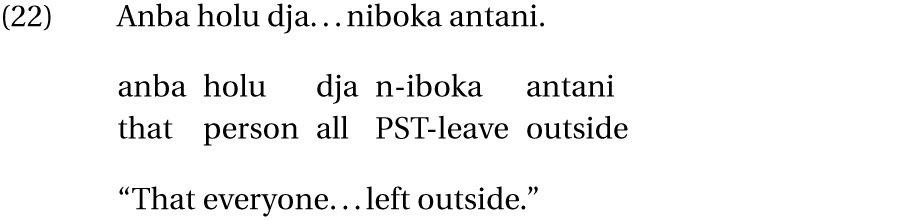

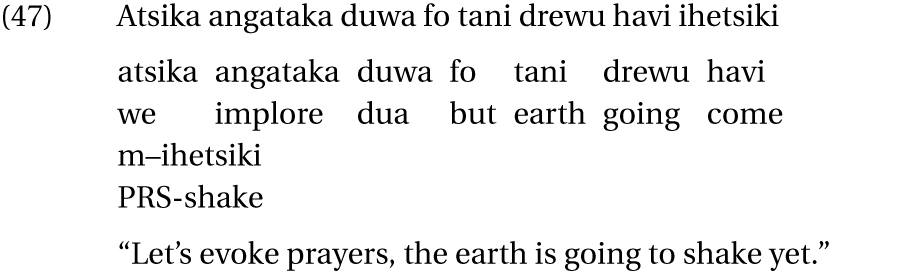

4.4. Evaluative language in the stories

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these short stories are filled with evaluative language [Martin and White 2005] given the highly disruptive nature of the earthquakes on people’s lives, particularly during the night. Indeed, the stories are filled with language that shows emotion and judgement, such as how people assess events. Starting with language expressing affect, “fear”, “surprise”, and “shock” were the principal emotions described in the stories via verb forms indicating “to be afraid” or “to be shocked”, as seen in Table 2. The verb for “shock” is similar in the two languages, -shanga, and this word can also describe a sense of worry depending on the context. Shimaore stories had another prominent verb, uria, which means to be afraid or to fear. In Kibushi, this is mavuzu. Terms for fear were often used to describe the overall reaction to the earthquakes in the night and the reason for going outside. Others feared that the house would collapse if they stayed inside.

Terms for evaluation in Shimaore and Kibushi

| Space | English | Shimaore | Frequency | Kibushi | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affect | Cry | keme | 11 | ||

| Affect | Afraid | ria | 37 | mavuzu | 3 |

| Affect | Shock | shanga | 15 | kushanga | 3 |

| Affect | Sad | hamu | 3 | mafurenyi | 0 |

| Affect | Problem | taãɓu | 5 | toiambu | 1 |

| Affect | Startle(d) | umaruha | 6 | tehitri | 6 |

| Affect | Difficult | dziro | 7 | mavestra | 1 |

| Affect | Destroy | komoha | 6 | midzutsu | 4 |

| Affect | Heart/soul | roho | 10 | ratsi | 1 |

| Affect | Tranquil | trulia | 8 | kutrulia | 1 |

| Affect | Mean | ratsi | 1 | ||

| Quantity | Everyone | piya | 42 | djabi | 15 |

| Quantity | We | wasi | 7 | atsika (zeheyi) | 7(1) |

| Quantity | Them | wawo | 5 | reu/ro | 24 |

| Quantity | Alone | weke | 42 | areki | 1 |

| Quantity | I | wami | 9 | zahu | 44 |

| Quantity | Each person | kula mutru | 15 | kula holu | 5 |

| Faith | God | (mwezi)mungu (allah) | 15(4) | draŋahari (mugu) | 2(1) |

The expression for shock or worry, -shanga, was employed in a similar way, as people were likely to be in shock after an earthquake. This feeling motivates many to go outside together, and is the reason why they could not sleep. When describing being woken up to the noise or movement of the earth shaking, storytellers use the verb umaruha (Sh) and the adjective tehitri (Ki), both of which describe being suddenly awakened or the state of being startled. We also see people describing their concern that the houses will be destroyed or damaged because of the tremors (komoha, Sh; midzutsu, Ki). While outside, storytellers describe hearing people crying and children screaming. Thus, we see various reactions to different aspects of the earthquakes: the act itself during the night, its potential occurrence, and the physical damage it could cause on the houses. Examples 41 through 48 show these words in context.

4.4.1. Shimaore

4.4.2. Kibushi

As seen, much of the evaluative language in the stories is negative, evoking undesirable sentiments and feelings. One expression used in the stories in Shimaore concerns the heart and/or soul, roho. Several participants use roho, with some talking about their hearts and/or souls being calmed when they heard the first call to prayer and knew that the night was over. Some storytellers spoke of God and desiring his mercy and forgiveness. Besides appealing to God for mercy prayers were made and the Quran was read to appease fears and anxieties. Terms used to refer to holy texts in the stories include yasini, msaafu and koran.

Another important linguistic aspect of the stories is the stress on the collective, which is a judgement made by the storyteller. Throughout the stories, activities and reactions are described in the plural form, either by using the expressions for describing “everyone” or conjugating verbs in plural form, both first person and third person. One Shimaore storyteller used the word piya (all/everyone) nine times in his short narrative and as seen in many examples, including 49 (Sh) and 50 (Ki). Participants repeated the adjectives to express that the actions in the stories—leaving, waiting, being shocked—were done not just by a handful of individuals, but by all of Mayotte. Repetition of these adjectives shows the stress put on the magnitude of the earthquakes in terms of their effects on the islanders. These were not some small tremors with little repercussion. Rather, storytellers position themselves via language as just one of many individuals who reacted in the same way during the night.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The goal of this article was to look at how language is used via narrative to recount the earthquake swarms of 2018 in Mayotte, including expressions regarding space, movement, and evaluation. It specifically looked at how Maore recounted, in Shimaore and Kibushi, their experiences during the earthquake swarm when they were compelled to leave their houses to seek refuge outside at night. Regarding the terminology for earthquakes, there appears to be a preference for the nominalized term in Kibushi, an established noun for “earthquake”, which is horuhoru tani. While some storytellers used a nominalized form in Shimaore, mdjidjimiyo, it was more common to use a verbal phrase equivalent to “the earth shook” or to borrow the French noun-forms. It is unclear why this difference exists for these two languages. Concerning the verbs used in the phrases describing the earth shaking in Shimaore, three stand out: udjidjima, ugudzua and uɗiha. While synonyms, these verbs appear to have slightly different semantic meanings: “tremble”, “shake” and “shift”, respectively. The word for “shake”, ugudzua, was used the most to describe the ground’s movement. Finally, in Shimaore, participants sometimes mentioned the earth or ground (tsi) itself moving but also sometimes talked about the surface of the earth moving (shivandre ya tsi).

Regarding other linguistic observations, the stories revealed a range of expressions for describing displacement either through verbs, such as those for “leaving”, “going up” or “going down”, or with prepositions and other markers of location and placement and various formulaic language was observed. Various activities were expressed in both languages. One principal observation is that the language used in the stories was very similar for Shimaore and Kibushi. Regardless of language (and by corollary, village), storytellers described their nighttime outdoor activities during the earthquake as including reading, waiting, sitting, and praying. This suggests that while there are villages that differ by language, there are strong cultural similarities. Finally, these similarities are also seen when storytellers evaluate events. The Shimaore and Kibushi terms for “shock” and “startle” are frequently used, suggesting that villagers all over the island experienced the earthquake swarm in a similar manner. We see via repeated, common language that storytellers express the extent to which many Maore acted similarly during the earthquake swarms, particularly at night. Emphasis on language that expresses an inclusive “all” and plurality such as activities being done by “us” and “them” shows how these activities are portrayed as occurring on a large scale, not just by a select, scared few. Various formulaic language was identified in the analyses, which could be exploited during awareness-raising campaigns. Little divergence between the two languages was observed considering the stories themselves or the language used in them, besides the nominalization of the word for “earthquake.”

The unprecedented earthquake swarm that struck Mayotte in 2018 incited unprecedented reactions from inhabitants. These reactions were better understood by asking people to recount their experiences during the months of relentless earthquakes, which is an established methodology (see Section 2.1). Narrative analysis revealed underlying similarities across villages in that people gathered in mass outside in order to wait out the night. In both local languages, storytellers describe villagers being afraid, in shock and startled. Movement in time and space plays an important part in the stories, which have a “there-and-back again” structure, in which the building interiors get indexed with danger and the exterior places index safety and unity. This indexing changes over time, because as the night wears on, the interiors become indexed with refuge, particularly once dawn arrives. Understanding reaction to this shared experience is important for risk management planning programs. For example, the fact that people gathered around mosques or that they read holy texts and prayed shows the importance of the Islamic faith on the island in moments of crisis and should not be ignored when considering how to approach risk prevention in Mayotte. Seeing that villagers all over the island left their homes and gathered in open areas indicates that certain spaces are privileged by default during certain crises. These aspects of the stories can be used when considering the local context for disaster planning.

Once again considering the local context, looking at how these events are recounted in Kibushi and Shimaore provide a small lexicography concerning earthquakes as well as spatial and evaluative language. There is still much to be learned about these two languages, particularly how they are used in specific contexts. While the study was modest in size and scope, it provides information on language in use on the island, such as established terms for “earthquake” or how the action associated with it is expressed. Linguistic analyses also offer insight into language use in a specific time and space envelope and how terms related to movement, emotion and evaluation are used. The various provided examples add to the existing literature on the languages, and can be exploited to help organizations charged with risk prevention and communication efforts in Mayotte’s local languages. There is still much to be learned and more research is needed looking at discourses of risk in Mayotte as realized by the population, including studies that include a larger and more diverse population sample. In addition, the media and governmental discourses around the earthquake swarms are yet to be fully understood, whether communicating in French, Shimaore or Kibushi. For the local languages, little media coverage exists, but the little that does, such as the televised evening news segment in Shimaore, has yet to be analyzed for its earthquake and other disaster narratives.

Conflicts of interest

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the participants for sharing their stories with me, the students who transcribed and translated texts, and Ahamada Kassime for his feedback on some grammatical aspects of Kibushi. I would also like to thank Narivelo Rajaonarimanana, Noel Gueunier, Mohamed Ahmed Chamanga, and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and thorough feedback. Any errors are my own. The Conseil scientifique of the CUFR helped fund transcription and translation services.

1 It is beyond the scope of the study to define the term narrative and narrative research in an exhaustive manner. In this article, I define “narrative” as a “recount (of) events in a sequential order” [De Fina 2003, p. 1].

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0