1. Introduction

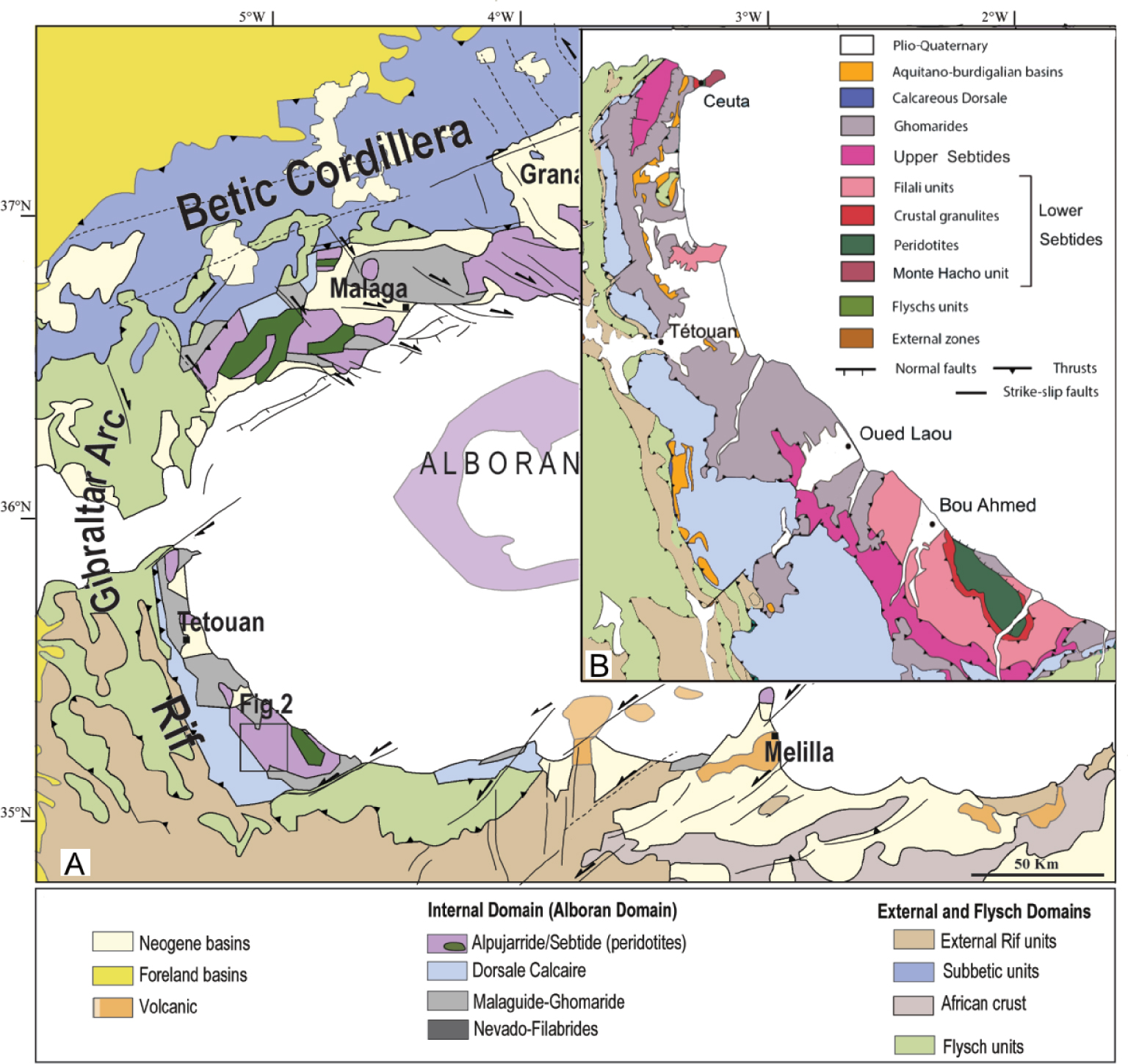

Located in the westernmost part of the western Mediterranean, the Gibraltar Arc forms an orogenic system that surrounds the Alboran Sea and includes the Rif Belt in northern Morocco and Betic Cordillera in southern Spain (Figure 1). Subduction followed by slab rollback is the currently accepted process to explain the alpine geodynamic evolution of the Betic-Rif belt [Spakman and Wortel 2004; Jolivet and Faccenna 2000; Verges and Fernandez 2012; van Hinsbergen et al. 2014; Leprêtre et al. 2018]. Two large peridotite massifs, namely, the Ronda massif in southern Spain and Beni Bousera massif in northern Morocco, crop out in the internal zone of this mountain belt (Figure 1) and are recognized as subcontinental mantle [Kornprobst 1969; Obata 1980]. In this portion of the western Mediterranean, the timing and processes for the emplacement of peridotite bodies into crustal rocks have been debated for decades. Various models have been proposed among which (1) a Permian–Early Mesozoic extensional tectonics related to Tethyan rifting [Reuber et al. 1982; Kornprobst and Vielzeuf 1984; Saddiqi et al. 1988; Chalouan and Michard 2004; Michard et al. 1991, 1997, 2002; Sánchez-Rodríguez and Gebauer 2000; Ruiz Cruz and Sanz De Galdeano 2014; Rossetti et al. 2020], (2) Oligo–Miocene delamination of the lithospheric mantle [Van der Wal and Vissers 1993; Platt et al. 2003], (3) Mesozoic extrusion of a mantle wedge during transpression along a subducting slab [Tubía et al. 2013; Mazzoli and Martín Algarra 2011], and (4) Oligocene–Early Miocene extension in a back-arc setting [Garrido et al. 2011; Afiri et al. 2011; Álvarez-Valero et al. 2014]. Depending on the authors, the early exhumation in an extensional context could be followed by a later exhumation process in a compressional context [e.g., Hidas et al. 2013; Précigout et al. 2013; Gueydan et al. 2019; Rossetti et al. 2020].

(A) Simplified structural map that highlights the position of the Alboran Domain and the localization of the current study. (B) Simplified structural map of the Internal Rif [modified after Chalouan et al. 2008 and El Bakili et al. 2020].

Recently, in the western Betics, Bessière [2019] performed structural and thermal analyses throughout the Dorsale Calcaire unit near the contact with the Ronda peridotites and Jubrique unit (Alpujarrides). Based on ophicalcite occurrences, magnetite mineralization, and oblique patterns of thermal structures with respect to the contact, this author interpreted the basal contact of the Triassic to Jurassic marbles from the Dorsale Calcaire unit over the Ronda peridotites as an extensional shear zone and proposed that the HT metamorphism observed in these series resulted from the exhumation of the Ronda massif in the tectonic framework of a hyperextended passive margin. Concomitantly, in the Internal Rif, Michard et al. [2020] described marbles that were localized between granulites of the Beni Bousera unit and gneisses of the overlying Filali unit and proposed that exhumation of the Beni Bousera unit took place during the Triassic–Jurassic in relation to the development of a hyperextended passive margin. However, to date, the existence of a Triassic–Jurassic syn-extensional metamorphic event has not been accurately demonstrated in the Gibraltar Arc.

In the Internal Rif, the Upper Sebtides (Federico units) crop out west of the Ceuta Peninsula to the north and west of the Beni Bousera massif in the south. They consist of a stack of metamorphic units that is composed of Permo-Triassic terrains overlying a Paleozoic basement, and is intercalated between the Dorsale Calcaire to the west and Lower Sebtides units to the east and is covered by the Ghomarides nappes.

In this paper, we present new structural, petrological, and 40Ar–39Ar geochronological data that were obtained from the Upper Sebtides metamorphic units west of the Beni Bousera massif. We document the discovery of an amphibolite facies metamorphic event that was coeval with peridotite emplacement within the continental crust during the Upper Triassic in relation to the rifting of Pangea and western Tethys opening.

2. Geological setting

The Betic-Rif orogen is subdivided into three main domains [Chalouan et al. 2008; Platt et al. 2013]: external domain, flysch domain, and internal domain. The internal domain, the so-called “Alboran domain”, is itself subdivided into three main zones. From top to bottom, they are the Mesozoic carbonate margin of the Alboran domain or “Dorsale Calcaire”, low-grade to un-metamorphosed sedimentary Paleozoic formations (the so-called “the Ghomarides”) and Sebtides units [Chalouan et al. 2008; Kornprobst 1974].

The Sebtides units are subdivided into Lower and Upper Sebtides (Figure 2). The Lower Sebtides represent a crustal metamorphic unit with Precambrian and/or Paleozoic protoliths, which contain at their base a massif of peridotites—and were affected by a metamorphism that is revealed by a succession of granulites, amphibolites, and greenschist metamorphic zones [El Maz and Guiraud 2001; Gueydan et al. 2015; Homonnay et al. 2018; Kornprobst 1974]. Recently, Farah et al. [2021] described a calcareous metasedimentary unit, the Beni Bousera marbles, that is localized between the kinzigites of the Beni Bousera unit and gneisses of the overlying Filali unit. The latter proposed that these carbonates were deposited over the crustal units of the Lower Sebtides during the Triassic–Lower Jurassic or tectonically emplaced as extensional rafts during the Lower–Middle(?) Jurassic.

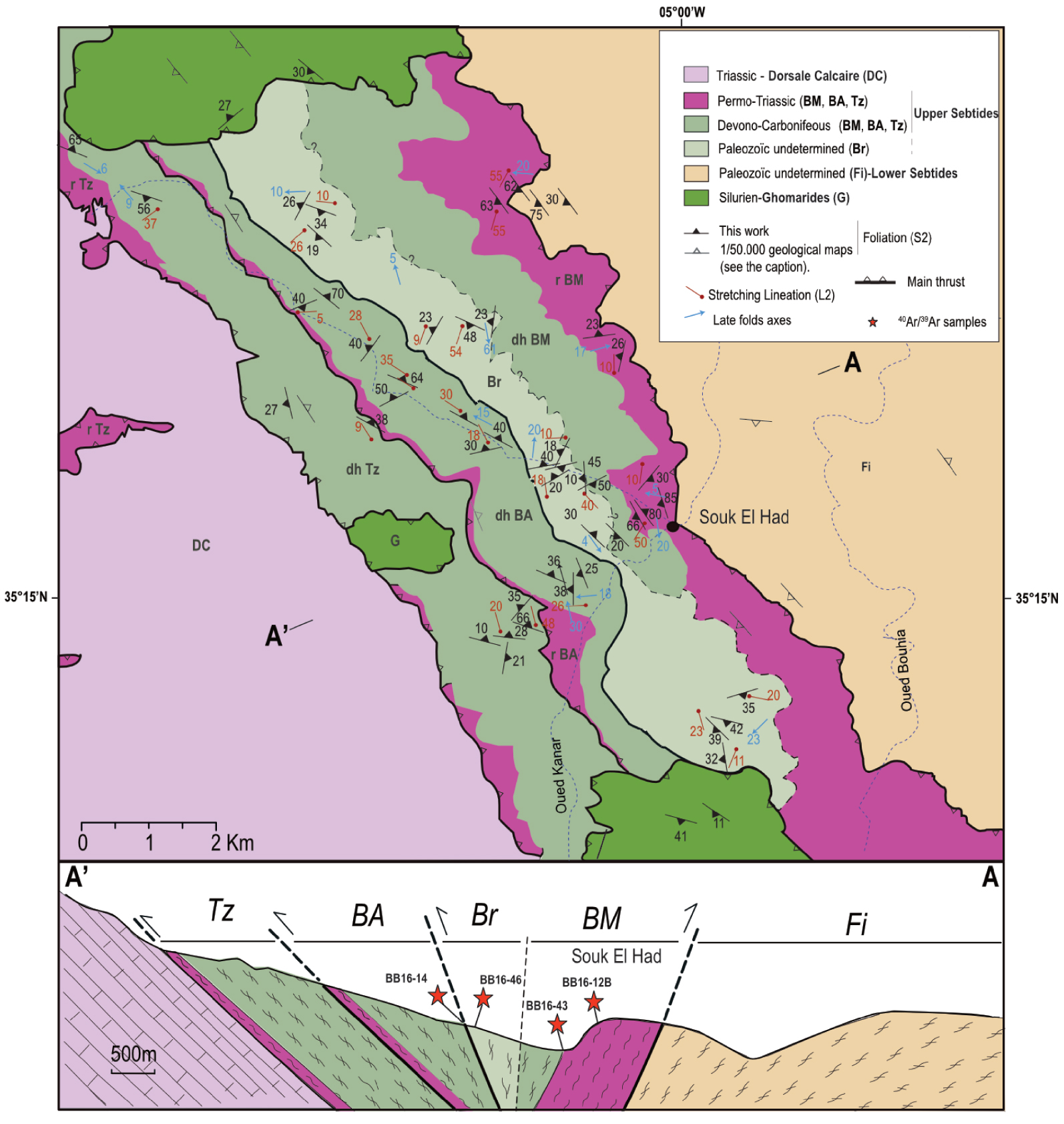

Geological sketch map and cross section of Souk El Had area [modified after Kornprobst 1959−1970; Ouazzani-Touhami 1986]. The stars show samples location used for geochronology. BB16-12B, N35° 15′ 46″/W04° 59′ 58″;

BB16-14, N35° 16′ 06″/W05° 01′ 13″; BB16-43, N35° 15′ 46″/W05° 00′ 26″; BB16-46, N35° 16′ 04″/W05° 01′ 0.1″. The foliation with empty symbols is from the 1/50,000 Bou Ahmed, and Talembote geological maps.

The Upper Sebtides outcrop is located in the northern part of the Inner Rif and is west of the Ceuta Peninsula and is in contact with the Ghomarides and forms the Beni Mezala antiform. In the southern part, to the west, and to the south of the Beni Bousera massif, they are wedged between the Filali and Dorsale Calcaire units and the Beni Mezala unit has been renamed Souk el Had unit [Ouazzani-Touhami 1986; Bouybaouene 1993; Michard et al. 2006; Chalouan et al. 2008]. The Upper Sebtides are composed of four superimposed units (Figure 2) that are distinguished by the intensity of their metamorphism [Durand Delga and Kornprobst 1963; Bouybaouene et al. 1995]: the Lower Beni Mezala unit (BM1), Upper Beni Mezala unit (BM2), Boquete de Anjeras unit (BA) and Tizgarine unit (Tz). These four units exhibit the same stratigraphic succession: (i) Devono-Carboniferous black schists and greywackes, (ii) a series of Permo-Triassic schists containing conglomerate levels, (iii) early Triassic quartzites, and (iv) finally Middle to Upper Triassic limestones and dolomites. The age of the Upper Sebtides formations is mainly established by facies correlations with other units of the Internal Rif. The greywackes and black schists of the Paleozoic formations are related to the Devono-Carboniferous [Durand Delga and Kornprobst 1963]. Concerning the Permo-Triassic formations, an Anisian age was paleontologically assigned to the dolostones of the Beni Mezala unit and Lower Triassic and Permian ages were assigned to the underlying quartzites and red sandstones, respectively, based on sedimentary continuity [Durand Delga and Kornprobst 1963]. In the Tizgarine unit, the red-purplish schists with intercalations of conglomerate formations were attributed to the Permian [Durand Delga and Kornprobst 1963] based on their analogy with facies that were paleontologically dated in the Ghomarides unit [Milliard 1959]. Other paleontological data obtained from the red sandstones of the Ghomarides unit provide a Middle Triassic age [Baudelot et al. 1984].

The Upper Sebtides units display high-pressure and low-temperature metamorphic conditions which are typical of subduction zones. They display contrasting P–T conditions depending on their tectonic position and their location north or south of the Internal Rif [Ouazzani-Touhami 1986; Bouybaouene 1993; Bouybaouene et al. 1995]. In the North (Ceuta area), the lower Beni Mezala unit P–T conditions range from 430–480 °C and 1.2–1.6 GPa up to 550 °C and 2 GPa. These values were estimated for the relics of Mg-Fe-carpholite–Mg-chlorite–chlorite and the talc–phengite–quartz–kyanite assemblage [e.g. Bouybaouene 1993; Chalouan et al. 2008]. At the upper Beni Mezala unit, relics of Mg-carpholite–Mg-chloritoid and quartz–kyanite give conditions ranging from 380–420 °C and 0.8–1 GPa to 430–450 °C and 1.2–1.5 GPa. In the Boquete de Anjeras unit, metamorphic conditions are estimated at T = 300–380 °C and P < 0.7 GPa for the sudoite–Mg-chlorite–Mg-chloritoid–pyrophyllite–phengite association. The Tizgarine unit is characterized by low-grade metamorphism under greenschist facies conditions (T < 300 °C and 0.1–0.3 GPa), with the association cookeite–Mg-chlorite–pyrophyllite–phengite.

In the south, the Souk el Had unit exhibits conditions of higher temperature and lower pressure than in the north, estimated at around 550–600 °C and 1 GPa. These conditions are determined by the combination of kyanite, phlogopite, and chloritoid. Moreover, the late crystallization of cordierite and andalusite (which replaces kyanite) has been identified only in these southern units. On the other hand, garnet–staurotide–biotite micaschists, constituting the Boured (Br) unit, outcrop between the units of Boquete de Anjeras and Beni Mezala. This intercalation of composition equivalent to that of the Filali micaschists is considered to belong to this unit [e.g. Chalouan et al. 2008]. The P–T conditions of the Boured unit were estimated at 680 °C and 0.7 GPa [Bouybaouene et al. 1995]. The P–T conditions of the Tizgarine and Boquete de Anjeras units remain similar.

Several geochronological studies have been carried out on the Beni Mezala units to determine the age of metamorphism. For the Southern Beni Mezala unit, K/Ar analyses on white micas yielded ages between 23.0 ± 3 Ma and 19.4 ± 1.2 Ma [Ouazzani-Touhami 1986]. For the BM1 and BM2 units, K–Ar and Ar/Ar analyses on phengite and retrograde white mica–clay mixtures [Michard et al. 2006] yielded ages between 23 and 20 Ma. U–Th–Pb ages of 21.3 ± 1.7 and 20.9 ± 2.1 Ma were obtained on retrograde monazites in the BM2 unit [Janots et al. 2006]. These ages are considered to correspond to the final exhumation of the Upper Sebtides units [Janots et al. 2006; Michard et al. 2006]. The age of the HP–LT metamorphism remains unknown.

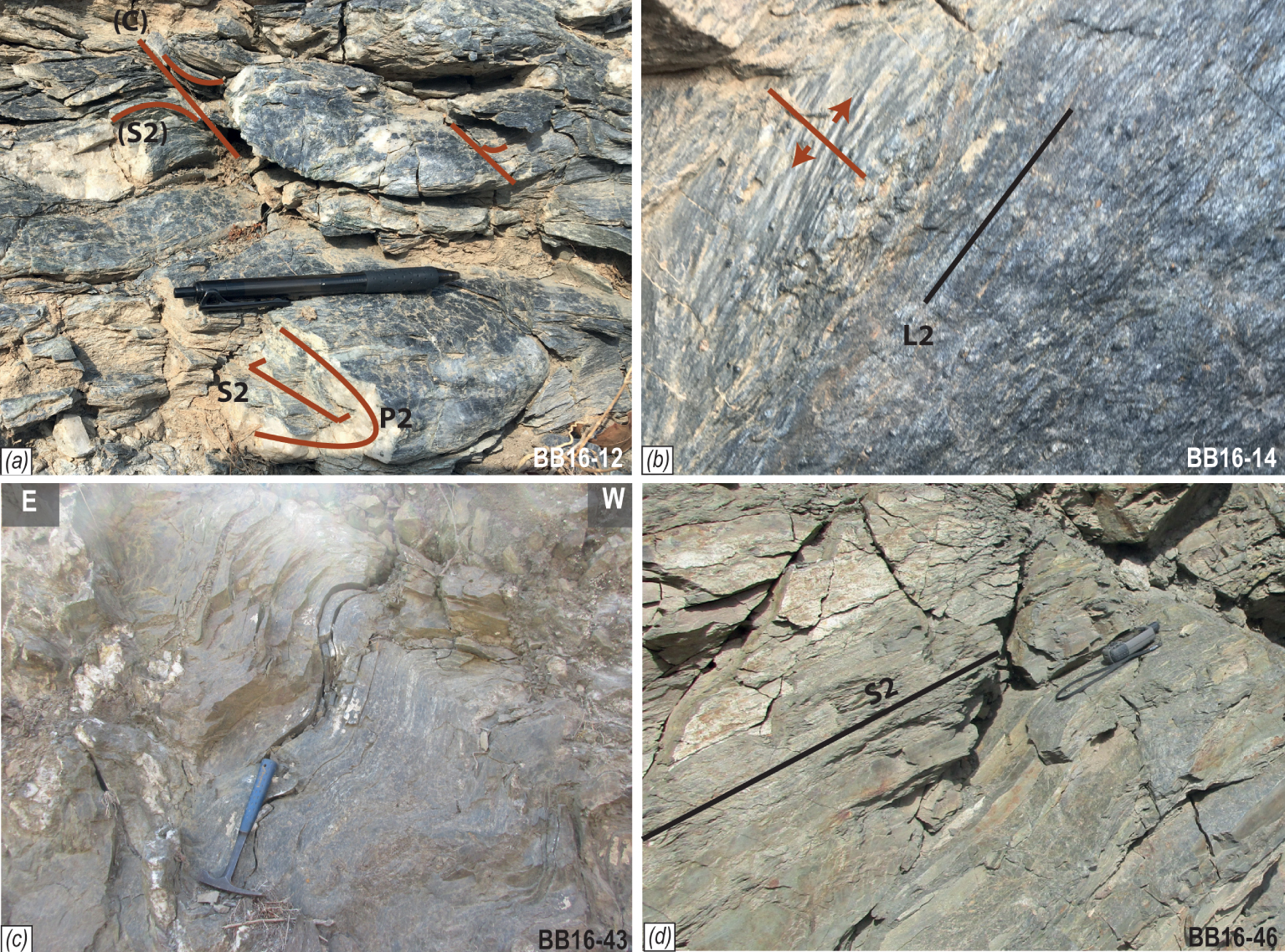

Field view of the Sothern Upper Sebtides units rocks in the Souk El Had Area. (a) Metapelite from the Permo-Triassic formation of the Southern Beni Mezala unit, notice the strong deformation marked by isoclinal syn-S2 folding and late extensional C/S structures (BB16-12); (b) mylonitic metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation of the Boured unit marked by a very strong stretching with open fractures perpendicular to the lineation (BB16-14); (c) metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation of the Beni Mezala unit, notice the main S2 foliation deformed by late folding (BB16-43); (d) metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation of the Boured unit (BB16-46).

3. Structural setting

In the Beni Bousera area, the structural pattern of the internal units is marked by kilometer-scale NW–SE trending folds that deform stacked metamorphic nappes. To the east, the Beni Bousera antiform shows, at its core, the Lower Sebtides units with peridotites, granulites, and marbles of the Beni Bousera unit, which are overlaid with micaschists and gneisses of the Filali unit. To the west, a fan-shaped structure reveals the youngest metamorphic units, and the Upper Sebtides are composed of Permo-Triassic formations and their Paleozoic basement (Figure 2). In this double vergence folded and thrusted structure, the Upper Sebtides units thrust over the Dorsale Calcaire unit westward and the Filali unit eastward (Figure 2). Each metamorphic unit of the Upper Sebtides is separated from the other by ductile shear zones. On the other hand, Paleozoic formations of the lowest Ghomarides nappes lie in tectonic unconformity over the Upper Sebtides units due to late extensional displacement [cf. Zaouia Fault; Chalouan et al. 1995].

In all Upper Sebtides units, the main dominant foliation, hereinafter called S2, mainly trends NW–SE and dips toward the SW in the Southern Beni Mezala and Boured units and toward the NE in the Boquete d’Anjera and Tizgarine units (Figure 2). At outcrop scale, the S2 foliation is parallel to P2 isoclinal folding (Figure 3a) and is highlighted by discrete discontinuity cleavages with planar disposition of minute white mica in the less-metamorphosed layers and concentrations of mica and garnet in the more-metamorphosed layers (Figure 3b,d). Foliation is often evidenced by synkinematic quartz veinlets (Figure 3a). The S2 foliation bears a stretching mineral lineation (Figure 2) that is defined by elongated quartz aggregates, alignment of metamorphic minerals in the metapelites (Figure 3b), and elongated pebbles in meta-conglomerates. As the tectonic contact between the different units is approached, the metapelites and metagreywackes are transformed into phyllonites, which are characterised by intense mylonitization within low-temperature ductile shear zones. Very strong stretching is also marked by a foliation boudinage (Figure 3b) that is perpendicular to the stretching lineations. S/C structures indicate a normal sense of shear (Figure 3a).

Early and relict S1 foliation is only observed at thin section scales (see Section 4 and Figure 4d). Locally, the main S2 foliation is crosscut by an S3 foliation that developed parallel to the axial plane of the late folds. Two late folding events are identified (Figures 2, 3c) by (1) NW–SE oriented open folds that are parallel to the Beni Bousera antiform and (2) NE–SW to E–W folds.

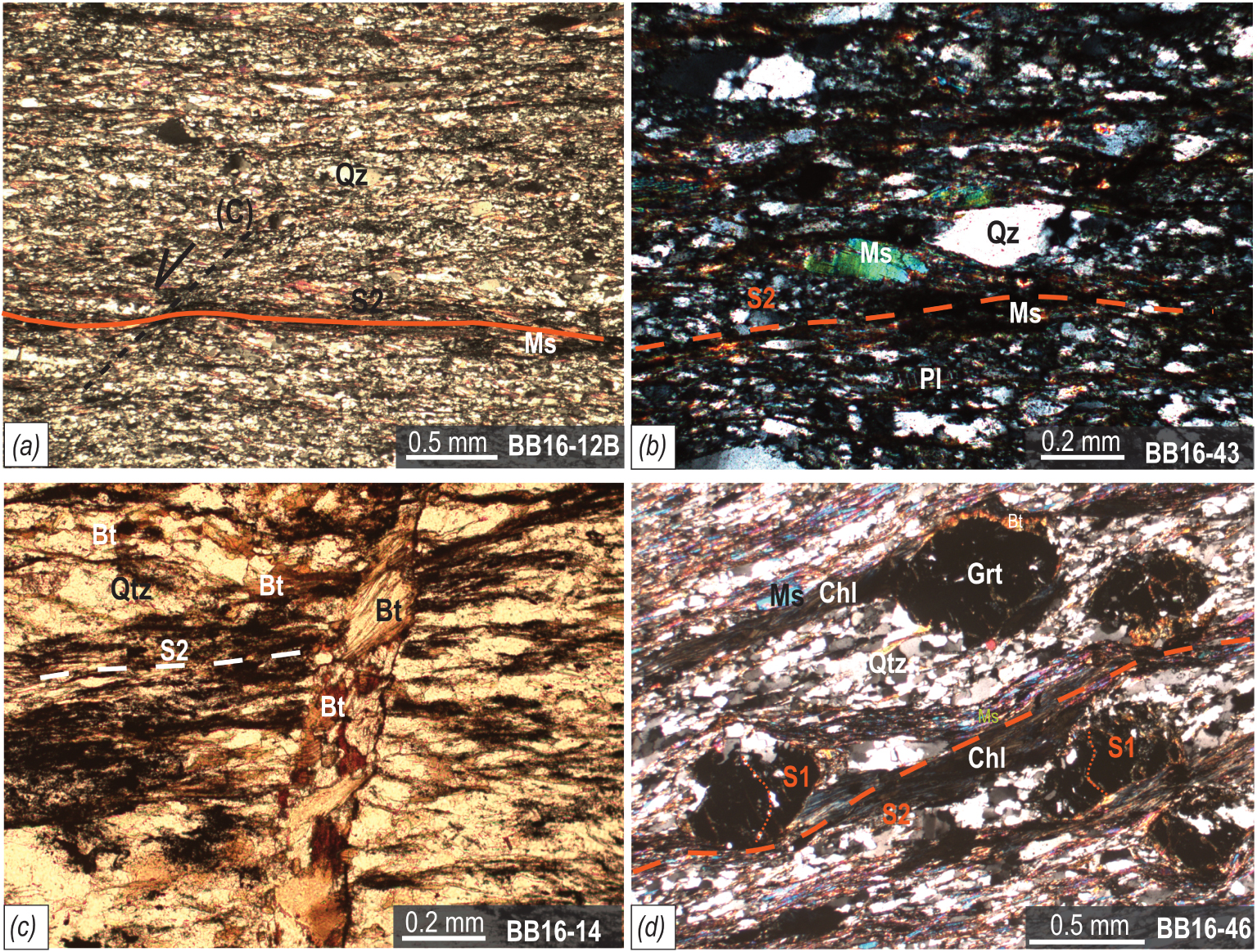

Photomicrographs illustrating the microstructures and the associated recrystallizations in the Upper Sebtides units; (a) metapelite from the Permo-Triassic (sample BB16-12B, Southern Beni Mezala unit; crossed polarized light); (b) mylonitic metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation (sample BB16-14, Boured unit; crossed polarized light); (c) metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation (sample BB 16-43, Southern Beni Mezala unit; plane-polarized light); (d) mylonitic metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation (sample BB 16-46, Boured unit; crossed polarized light). Mineral abbreviations after Kretz [1983].

4. Mineralogy and microstructures

At the regional scale, the metasediments (i.e., metapelites and metagreywackes) of the Southern Upper Sebtides units display a main dominant foliation, S2, that is defined by well-oriented muscovite, biotite, chlorite, and ilmenite and by dynamically recrystallized quartz and albite-rich ribbons. This typical and ubiquitous mineral assemblage, hereinafter called M2, is diagnostic of greenschist facies conditions in metasediments [Spear 1993; Frey and Robinson 1999; White et al. 2000; Bucher and Frey 1994]. In some samples, numerous pre-S2 phases occur as large porphyroclasts of K-feldspar, plagioclase, quartz, and white mica, particularly in the metagreywacke, and as white micas, biotite, and garnet in the metapelites. This early assemblage, hereinafter called M1, is characteristic of amphibolite facies metamorphism [Maruyama et al. 1983; Spear 1993; Johnson et al. 2008; Couëslan and Patison 2012]. Muscovite, biotite, and plagioclase porphyroclasts exhibit textural evidence of ductile intracrystalline deformation (i.e., subgrain development and kinking resulting in marked undulose extinctions and dynamic recrystallization of new grains). K-feldspar porphyroclasts behave in a brittle-ductile manner (i.e., microfractures, rigid rotations, undulose extinctions). Garnets are generally wrapped by S2 foliation and display pressure shadows that are filled by chlorite and quartz. In some samples, early schistosity (S1) is preserved as inclusion trails within the garnet porphyroclasts (Figure 4d).

Our strategy for Ar/Ar dating is based on these microstructural observations. On the one hand, to obtain robust age data for the M2 metamorphism, we selected two samples (e.g., BB 16-12 and BB 16-14), which were fully recrystallized under greenschist facies conditions with well-developed S2 foliation and with only rarely preserved porphyroclasts. On the other hand, to date the M1 amphibolite facies assemblage, we selected two metagreywacke samples (e.g., BB 16-43 and BB 16-46) that are particularly rich in porphyroclasts. Detailed descriptions of these samples are presented as follows:

- BB16-12 is a metapelite from the Permo-Triassic formation of the Southern Beni Mezala unit. The main S2 foliation is emphasized by alignment of white micas, quartz ribbons, ±biotite, and ±chlorite porphyroblasts, which define the M2 metamorphic assemblage. Medium-grained layers with porphyroblasts (grain size ∼200–300 nm) alternate with a fine-grained mosaic (grain size ∼25–50 nm) that is composed of recrystallized quartz, feldspars, and micas.

- BB16-14 is a mylonitic metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation of the Boured unit that is in tectonic contact with the Boqueta Anjera. Mylonitic foliation is characterized by elongated quartz ribbons, syn-S2 white micas, chlorite, and ±biotite. Veinlets are filled by chlorite, biotite, white micas, quartz, and calcite (grain size ∼300–500 nm) and developed perpendicular to the main S2 foliation. The mineralogical content of these veinlets is in equilibrium with the syn-S2 assemblage and is typical of greenschist facies. Garnet and white mica porphyroclasts are the main minerals that are related to the M1 metamorphic assemblage.

- BB 16-43 is a metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation of the Southern Beni Mezala unit. The main S2 foliation is marked by the development of small white micas, chlorite, quartz, and plagioclase (grain size ∼50–100 nm). Large white mica, quartz, plagioclase, and K-feldspar porphyroclasts (grain size ∼200–300 nm) are characteristic of the M1 metamorphic assemblage. The large white micas display recrystallized rims and undulose extinction.

- BB 16-46 is a mylonitic metagreywacke from the supposedly Paleozoic formation of the Boured unit. The main S2 foliation is characterized by chlorite, quartz, white mica, and ±biotite. Chlorite developed in the pressure shadows of garnet porphyroclasts that contain inclusion trails truncated by the S2 foliation. Biotite, white mica, and garnet porphyroclasts are wrapped by quartz ribbons and form the M1 metamorphic assemblage.

5. 40Ar–39Ar data

5.1. Methodology

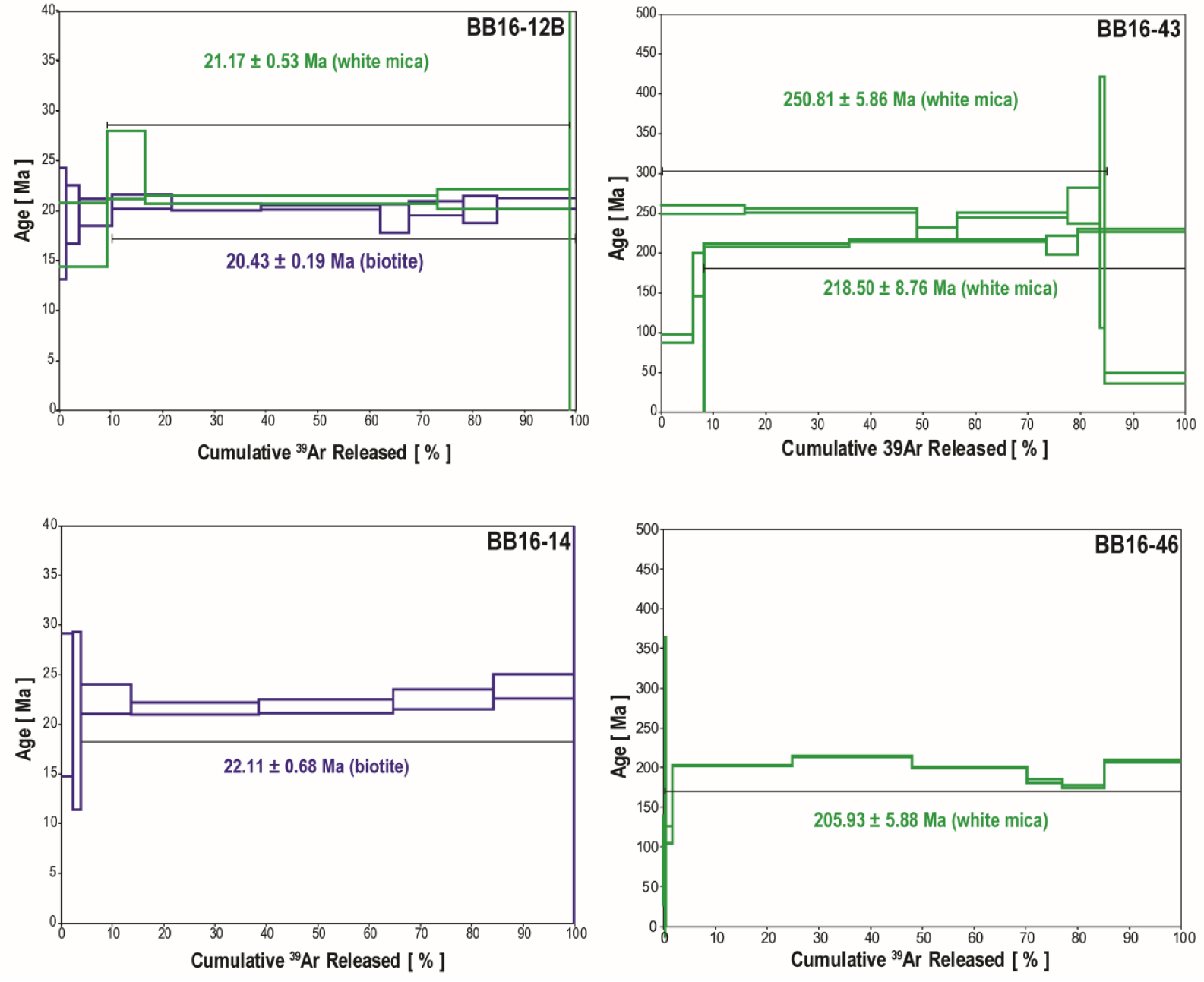

Two samples were collected from the Boured unit (Figures 2, 3, and 4): BB16-14 is a phyllonite that resulted from strong ductile deformation of the metagreywackes of the Paleozoic formation near the contact with the Boqueta Anjera unit and BB16-46 is a mylonitic metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation that is located more distantly from this tectonic contact. Two other samples were collected in the Southern Beni Mezala unit (Figures 2, 3, and 4): BB16-12 is a metapelite from the Permo-Triassic formation and BB 16-43 is a metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation. The corresponding 40Ar/39Ar age spectra are presented in Figure 5.

40Ar∕39Ar age spectra as a function of 39Ar released. The error boxes of each step are at the 2𝜎 level. The error of ages is given at the 2𝜎 level. Ages were calculated using the ArArCalc software [Koppers 2002]. Raw data are presented in Supplementary Data.

Samples BB16-12, BB16-14, and BB16-43 were analyzed in the Géoazur laboratory. Then, considering the singularity of the Triassic age obtained from sample BB16-43 and to test its robustness, we proceeded to analyze (in the Geosciences Montpellier laboratory) a Supplementary sample (BB16-46), which was collected from the same lithology.

Raw data from each step and blank were processed, and ages were calculated using ArArCALC software [Koppers 2002]. The analytical procedures and raw data can be downloaded from the Supplementary materials.

5.2. Results

∙ Sample BB16-12B is a metapelite from the Permo-Triassic of the Southern Beni Mezala unit.

A single biotite grain yielded a plateau age of 20.43 ± 0.19 Ma, which corresponds to 89.72% of 39Ar released and to 7 steps. The inverse isochron for the plateau steps provides a concordant age at 20.31 ± 0.59 Ma (MSWD = 1.14; initial 40Ar/36Ar ratio of 316.14 ± 82.89 Ma). The age of 20 Ma can be considered as the most accurate age.

A single white mica grain yielded a plateau age at 21.17 ± 0.53 Ma, which corresponds to 89.42% of 39Ar released and to 4 steps. The inverse isochron for the plateau steps provides a concordant age at 21.82 ± 0.42 Ma (MSWD = 2; initial 40Ar/36Ar ratio of 134.38 ± 90.65 Ma). The age of 21 Ma can be considered as the most accurate age.

The biotite and white mica ages between 21 and 20 Ma are concordant, as indicated by the error bars.

∙ Sample BB16-14 is a mylonitic metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation of the Boured unit.

A single biotite grain yielded a plateau age at 22.1 ± 0.68 Ma, which corresponds to 95.91% of 39Ar released and to 5 steps. The inverse isochron for the plateau steps provides a concordant age at 22.18 ± 1.00 Ma (MSWD = 3.13; initial 40Ar∕36Ar ratio of 295.85 ± 30.97 Ma). The age of 22 Ma can be considered as the most accurate age.

∙ Sample BB16-43 is a metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation of the Southern Beni Mezala unit.

A single white mica grain yielded a weighted age at 218.5 ± 8.76 Ma, which corresponds to 91.97% of 39Ar released and to 4 steps. The staircase spectrum with younger ages at the low-temperature steps suggests slight radiogenic argon loss and 218 Ma can be considered as the minimum age.

A single duplicate white mica grain yielded a very disturbed spectrum-weighted age of 250.81 ± 5.86 Ma, which corresponds to 84.45% of 39Ar released and to 4 steps. The saddle-shaped age spectrum suggests post-isotopic closure disturbances of the analyzed white mica, and 250 Ma can be considered as the maximum age.

The most accurate estimate for the metamorphic event that is provided by the white micas is approximately 220 Ma.

∙ Sample BB16-46 is a metagreywacke from the Paleozoic formation of the Boured unit.

A single muscovite grain yielded a weighted age at 205.93 ± 5.88 Ma, which corresponds to 83.51% of 39Ar released and 6 steps. The slightly perturbed spectrum for the first steps at low temperatures can reflect an excess of argon, so 206 Ma should be considered as the maximum age.

6. Discussion

6.1. Geochronology

The new geochronological data obtained for the Southern Upper Sebtides units display two different sets of ages, namely, Lower Miocene and Upper Triassic. Ages between 21 and 20 Ma were obtained for white mica and biotite from samples BB16-12 (Permo-Triassic formation of the Southern Beni Mezala unit) and BB16-14 (Paleozoic formation of the Boured unit). The analyzed minerals are porphyroblasts that developed in the S2 foliation plane or in syn- to late S2 veinlets. These ages correspond to the M2 greenschist facies metamorphic event and are similar to those previously obtained by several authors for the Upper Sebtides units. West of the Beni Bousera antiform in the Souk el Had area, K/Ar analyses on white micas from the metapelites of the Southern Beni Mezala unit have yielded ages of 19.4 ± 1 Ma and 23 ± 3 Ma [Ouazzani-Touhami 1986]. To the north in the Beni Mezala antiform, K–Ar and Ar/Ar analyses performed in the Northern Beni Mezala units on phengite [Saddiqi 1995] and on retrograde white mica–clay mixtures [Michard et al. 2006] have yielded ages between 23 and 20 Ma. U–Th–Pb ages of 21.3 ± 1.7 and 20.9 ± 2.1 Ma were also obtained for retrograde monazites in the metapelites of the Northern Beni Mezala units [Janots et al. 2006]. This Lower Miocene metamorphic event is observed throughout the Alboran domain and is associated with a thermal event that was related to the back-arc Alboran basin opening [El Bakili et al. 2020].

Ages of 218.5 ± 8.76 Ma and 250.81 ± 5.86 Ma were obtained for M1 white mica porphyroclasts from samples BB16-43 (Paleozoic formation of Southern Beni Mezala unit) and an age of 205.93 ± 5.88 Ma was obtained for M1 white mica porphyroclasts in sample BB16-46 (Paleozoic formation of the Boured unit). The 40Ar∕39Ar age spectra obtained for the white mica porphyroclasts from metagreywackes show significant perturbations, suggesting post-isotopic closure disturbances that make interpreting these spectra difficult. We cannot exclude the possibility of a partial re-opening related to fluid circulation or to later metamorphic events. However, ages at 218.5 ± 8.76 Ma and 205.93 ± 5.88 Ma were obtained for rocks that were sampled in two different geological units of the Upper Sebtides and were analyzed in two distinct laboratories with different analytical conditions. Both ages display good reproducibility and concordance relative to the error bars, which argue in favor of their geological consistency and suggest that a metamorphic event occurred for the amphibolite facies in the Upper Sebtides during the Upper Triassic.

The protolith age of these formations is dated by facies analogy in comparison to the other units of the Internal Rif. The metagreywackes come from the Paleozoic formations attributed to the Devono-Carboniferous [Durand Delga and Kornprobst 1963]. If the white mica were detrital, the protolith of these formations would be younger than the Upper Triassic, which would correspond to the youngest age obtained for those micas. This is not consistent with their structural position under the metapelite, dolomitic limestone, and dolostone formations that are attributed to the Permo-Triassic [Durand Delga and Kornprobst 1963]. For this case, the upper Paleozoic age (or older) of the metagreywackes is confirmed, and the dated micas resulted from a Triassic metamorphic event that affected these formations under amphibolite facies conditions. Such Triassic ages, which are indicative of a metamorphic event, are described for the first time in the Upper Sebtides units of the Internal Rif. The only similar age at 202.45 ± 0.98 Ma was obtained by 40Ar∕39Ar at Cap des Trois Fourches in the Eastern Rif for white mica porphyroclasts from mylonitic orthogneisses [Azdimousa et al. 2018].

6.2. Geodynamic implications

The different Triassic formations of the internal units (e.g., Dorsale Calcaire, Ghomarides–Malaguides, and Sebtides–Alpujarrides) are continuous on both sides of the Gibraltar Arc. Although their relative positions are still debated, it is commonly accepted that they constitute the continental margin of the western Tethysian ocean during this period [Leprêtre et al. 2018; Gimeno-Vives et al. 2019; Michard et al. 2021]. Except for the Dorsale Calcaire unit that detached from its basement, the other units rest without major tectonic discontinuities above their Paleozoic basement, whose thickness was reduced as a consequence of significant crustal thinning [e.g., Chalouan et al. 2008; Martin-Rojas et al. 2009]. Moreover, such crustal thinning during the late Permian–Triassic period is especially highlighted in the Betics by stretching rates, subsidence, and rift basin detrital deposits [Hanne et al. 2003; Martin-Rojas et al. 2009; Angrand et al. 2020] and corresponds to the break up of Pangea at the Central and North Atlantic–Tethys triple junction [Fernandez 2019]. Major rifting started in the Middle to Late Triassic along the Central Atlantic [Stampfli 2000; Ellouz et al. 2003; Davison 2005; Frizon de Lamotte et al. 2008; Gouiza 2011; Leleu et al. 2016].

In the core of the Beni Bousera antiform, which is located only a few kilometers west of the study area, marbles revealed a stratigraphic sequence that is evocative of the Middle to Upper Triassic series of the Alpujarrides–Sebtides units [Farah et al. 2021; Michard et al. 2021]. Considering that these marbles were unconformably deposited above the granulitic metapelites of the Beni Bousera unit, the authors propose that the Beni Bousera subcontinental peridotites were exhumed at a short distance from the surface as early as the Triassic in the context of a hyperextended margin. It is worth noting that in the Eastern Rif, the Upper Triassic age of the mylonitic orthogneisses was considered to possibly have resulted from a heat anomaly that was related to the rifting event that led to the opening of the Tethys Ocean [Azdimousa et al. 2018]. On the other hand, in the External Rif, a major magmatic event, the so-called Mesorif Gabbroic Complex (MGC), occurred in the range of 190–200 Ma [Benzaggagh et al. 2014; Michard et al. 2018; Gimeno-Vives et al. 2019]. Two distinct interpretations of the MGC emplacement are proposed either within the continental crust during the Late Triassic to Early Jurassic [Leprêtre et al. 2018; Gimeno-Vives et al. 2019] or into an Early Jurassic oceanic domain that coincides with the onset of oceanic floor formation in the Central Atlantic [Michard et al. 2018, 2020]. Whatever the interpretation, the MGC indicates important thinning of the continental lithosphere before the Middle Jurassic rifting [Gimeno-Vives et al. 2019; Michard et al. 2021]. Furthermore, in the western Betics, in the Ronda massif, the Triassic to Jurassic Dorsale Calcaire unit [Martin-Algarra 1987] is strongly metamorphosed at its contact with the peridotites [Mazzoli et al. 2013]. Based on the isotherm geometry deduced from Raman spectrometry, Bessière [2019] showed that the isograds of this high-temperature metamorphism are oblique to the contact between these units and are compatible with an extensional context. However, no precise age has been determined for this metamorphic episode. A similar metamorphic context is described in the Pyrenean belt, in which the pre-rift Mesozoic sediments of the passive margins experienced Upper Cretaceous high-temperature–low-pressure metamorphism that postdates the mantle exhumation [Golberg and Leyreloup 1990; Jammes et al. 2009; Clerc and Lagabrielle 2014; Lagabrielle et al. 2019]. Permian–Triassic metamorphism, coeval with mafic magma intrusions, is also well documented in the alpine belt, where it is regarded as the witness of the rifting event that led to the Pangea break up and Jurassic Alpine Tethys opening [Lardeaux and Spalla 1991; Spalla et al. 2014; Roda et al. 2019]. Specifically, high-temperature and low-pressure Permian metamorphic evolution is currently recognized in the Austro-Alpine domain [Lardeaux and Spalla 1991; Rebay and Spalla 2001; Manzotti et al. 2012], while Permian to Triassic metamorphism is described in the Variscan basement rocks of the Southern Alps [Diella et al. 1992; Bertotti et al. 1993; Sanders et al. 1996].

Therefore, we propose that the Upper Triassic metamorphism in the Upper Sebtides units of the internal Rif could result from a significant crustal and lithospheric thinning that formed a hyperextended margin between Iberia and Africa and caused mantle exhumation in the Alboran domain during Jurassic times.

7. Conclusion

Wedged between the Lower Sebtides and Dorsale Calcaire units of the Internal Rif, the Upper Sebtides units correspond to an intensively thinned continental crust. Our new petrological and geochronological data, which were obtained from the Upper Sebtides metamorphic units west of the Beni Bousera massif, demonstrate that an amphibolite facies metamorphic event occurred during the Upper Triassic. We ascribe this metamorphic event, which was discovered for the first time in the internal Rif, to a thermal perturbation that was driven by crustal thinning during the earlier stages of the western Tethys opening. Later, these units experienced a Lower Miocene greenschist facies metamorphic event that was related to back-arc extension in the Alboran basin.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dominique Frizon de Lamotte, André Michard, and the editor Michel Faure for their constructive reviews that improved the manuscript. This work has been funded by FP7-IRSES-MEDYNA project.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0