1 The global mean energy budget

The elements of the Earth's radiation budget (ERB), viz. the incident and reflected solar radiation fluxes (irradiances), and the thermal infrared radiation flux emitted to space, constitute the quasi totality of energy exchanges between the planet and its cosmic environment, and can only be observed from outside the atmosphere, i.e. from space (Fig. 1). Planetary radiation balance or net radiation RN at the “top of the atmosphere” (TOA) is then given by:

| (1) |

The Earth's radiation and energy budget. On the left, the practically parallel Sun's rays (vertical arrows) illuminate planet Earth, which reflects this solar radiation anisotropically (dotted arrows, for one sunlit location). Thermal infrared radiation is emitted anisotropically (wavy arrows) from both sunlit and night sides. An instrument outside the atmosphere measures samples of these anisotropically reflected shortwave and emitted longwave radiances. On the right, global mean terms of the ERB at the top of the atmosphere (TOA) are, from left to right, incident solar irradiance (or flux), reflected solar flux, and emitted thermal longwave flux (cf. Eq. (1)). At the surface, from left to right, downward solar flux F↓SW (S), upward (reflected) solar flux αSF↓SW (S), non-radiative latent heat and sensible heat fluxes LE and S, downward LW flux F↓LW (S) and surface emission or upward LW flux σTS4 (cf. Eq. (4)). All of these terms (except for the zero nighttime solar flux) are of order 10 to 350 Wm−2; see Table 3. Global mean heat flux from the Earth's interior to the surface is of order 0.1 Wm−2 and not shown here. Masquer

The Earth's radiation and energy budget. On the left, the practically parallel Sun's rays (vertical arrows) illuminate planet Earth, which reflects this solar radiation anisotropically (dotted arrows, for one sunlit location). Thermal infrared radiation is emitted anisotropically (wavy arrows) from ... Lire la suite

Bilans radiatif et énergétique de la Terre. À gauche, les rayons solaires pratiquement parallèles (flèches verticales) éclairent la planète Terre, qui renvoie ce rayonnement solaire vers l’espace de manière anisotrope (flèches en pointillé, pour un lieu éclairé). L’émission anisotrope (flèches ondulantes) de rayonnement infrarouge thermique a lieu côté jour, comme côté nuit. Un instrument en dehors de l’atmosphère peut mesurer des échantillons de ces luminances réfléchies (ondes courtes) et émises (ondes longues). À droite, les moyennes planétaires des éléments du bilan radiatif de la Terre au « sommet » de l’atmosphère (TOA) sont, de gauche à droite, l’irradiance solaire incidente, le flux solaire réfléchi, et le flux thermique ondes longues émis (Éq. (1)). À la surface, de gauche à droite, le flux solaire descendant F↓SW (S), le flux solaire montant (réfléchi) αSF↓SW (S), les flux non radiatifs de chaleur latente et de chaleur sensible, le flux ondes longues descendant F↓LW (S) et l’émission de la surface du flux ondes longues montant σTS4 (cf. Éq. (4)). Tous ces termes sont de l’ordre de 10 à 350 Wm−2 (sauf pour le flux solaire de nuit, nul) : voir le Tableau 3. Le flux moyen de l’intérieur de la Terre vers sa surface, de l’ordre de 0,1 Wm−2 n’est pas montré. Masquer

Bilans radiatif et énergétique de la Terre. À gauche, les rayons solaires pratiquement parallèles (flèches verticales) éclairent la planète Terre, qui renvoie ce rayonnement solaire vers l’espace de manière anisotrope (flèches en pointillé, pour un lieu éclairé). L’émission anisotrope (flèches ... Lire la suite

Here, the first term on the right-hand-side gives the globally averaged absorbed solar flux, where S is the “solar constant”, i.e. total solar irradiance (TSI) at the mean Earth–Sun distance (one astronomical unit, 1 AU), a is the Sun–planet distance expressed in AU, and α is the planetary albedo (the Bond albedo, giving the fraction of incident global mean solar flux reflected or scattered to space). The factor (1/4) arises from the ratio of the nearly spherical planet's cross-section to its surface. Term FLW is the globally averaged thermal “longwave” radiation flux to space, often written in terms of an effective temperature Te as FLW = σ Te4 where σ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant.

For Earth and the other terrestrial planets (but not for the giant planets), the global mean radiation fluxes exchanged with space are far greater than the globally averaged heat fluxes emerging from the interior, by more than three orders of magnitude for the Earth. In what follows, we neglect this term and consider only the radiation budget terms as fundamental in determining the energy state of the planet. Thus, for the planet's climate – characterized by the energy state of the surface and atmosphere – to be in equilibrium, the planetary radiation balance, i.e. the difference between the absorbed solar radiation flux and the emitted thermal infrared radiation flux, must be zero. Because of anthropogenic intensification of the atmospheric greenhouse effect over recent decades, the Earth's climate system is not now in an equilibrium state, with significant warming occurring in the lower atmosphere and at the surface as well as in the ocean down to at least several hundred meters depth (Antonov et al., 2004; Levitus et al., 2000, 2005). The observed ocean warming together with model calculations (Hansen et al., 2005) indicate that the Earth's radiation balance should now be positive and approaching + 1 Wm−2, a value within the uncertainty of satellite determinations (Kandel and Viollier, 2005; Kiehl and Trenberth, 1997; Loeb et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 2009; Trenberth et al., 2009), but an order of magnitude greater than the heat flux from the Earth's interior.

Effective temperature Te depends on temperatures at the surface and in the layers of the atmosphere from which longwave radiation reaches space. Because of the atmospheric greenhouse effect, it is significantly lower than globally averaged surface temperature, an often-used parameter of climate. Using a normalized greenhouse factor g originally defined (Raval and Ramanathan, 1989) for cloud-free ocean areas, we can write:

| (2) |

The above discussion applies to radiation budget terms at the “top of the atmosphere” (the TOA ERB), where the TOA level is often taken at altitude 30 km even though the stratosphere and higher layers are not totally transparent to either SW or LW radiation. To understand climate and climate change at the surface, all terms of the energy budget must be considered, not only surface radiation balance (Kandel, 1981; Möller, 1963). Surface energy balance (cf. Fig. 1) can be written as:

| (3) |

where LE and H are respectively the global mean latent and sensible heat fluxes from surface to atmosphere, and RN(S) is the global mean surface radiation balance.

| (4) |

Here, F↓SW and F↓LW are downward SW and LW fluxes from the atmosphere at the surface; upward LW flux from the surface is taken as σTS4, incorporating in TS effects of non-unity surface emittance.

Similarly, understanding atmospheric changes requires consideration of the atmospheric energy balance:

| (5) |

Atmospheric radiation balance RN(atm) can also be written as

| (6) |

In these equations, the only unambiguously measured terms are solar constant S and Sun–Earth distance a. The global mean terrestrial terms are important parameters of the functioning of the Earth system, obtained by averaging space- and time-dependent terms themselves derived from quantities measured at the surface, in the atmosphere, and from space.

2 From real measurements to the Earth's radiation and energy budgets

Elements of the planet's (TOA) radiation budget can only be observed from space, but estimates were made as early as 1908 (Hunt et al., 1986) on the basis of very limited radiation measurements made at the surface. It was early recognized (Abbot, 1920) that clouds are major contributors to both reflection of incident solar radiation and blocking of thermal LW radiation to space from the Earth's surface, and so surface-based estimates of cloud cover were crucial. Independent of such estimates, however, Danjon, 1928 developed an alternative method of estimating Earth's albedo, using ground-based observations of lunar lumière cendrée or earthshine, in effect using virtual lunar-based observation of the Earth's reflection of solar SW toward the Moon. Danjon recognized, however, that the space–time sampling involved was extremely limited (cf. also (Kandel, 1994)). These limitations apply equally to modern earthshine-based albedo estimates (Goode et al., 2001; Pallé et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 2003), which in any case are spectrally limited by the atmosphere. Hence claims that earthshine monitoring reveals significant albedo variations (Pallé et al., 2004) cannot be accepted (Loeb et al., 2007b; Wielicki et al., 2005). Pre-satellite estimates of LW emission to space relied on relatively crude considerations of atmospheric vertical structure.

Systematic measurements of total solar irradiance (TSI, at a Sun–Earth distance of 1 AU) have been made since early in the space age, and systematically since the 1970s. Well before the first rocket flights, over the first half of the 20th century, C.G. Abbot and co-workers of the Smithsonian Institution had used measurements from high-altitude stations to determine incident solar radiation flux. They estimated average incident solar flux at 1.946 cal cm−2 min−1 (= 1357 Wm−2) and claimed to have found significant variations correlated with solar activity and terrestrial weather. However, Sterne and Dieter (Sterne and Dieter, 1958) showed that these variations were mostly spurious and that real solar flux variations were probably smaller than 0.17%.

Although determinations of TSI from space (systematic since Nimbus-7 in 1978) have ranged from 1360 to 1375 Wm−2 (some earlier determinations as high as 1391 Wm−2), these differences are essentially of instrumental origin. In what follows, we take as “best value” 1367 Wm−2 (Fröhlich, 2000; Fröhlich and Lean, 2004), although some recent results indicate that this is still subject to instrumental bias, and that the solar constant (TSI at 1 AU) is closer to 1361 Wm−2 (Kopp et al., 2005). Independent of such instrumental adjustments, it remains clear that intrinsic variations of the solar constant are only 0.1% with the 11-year solar activity cycle (Fröhlich, 2000; Fröhlich and Lean, 2004; Lean, 2005). Longer-term changes not directly measured from space may exist, but from indirect evidence they appear to be smaller than 0.2% over the last 9300 years (Fröhlich, 2009; Steinhilber et al., 2009). Shorter-term fluctuations, reaching 0.4% on time scales from days to weeks, are irrelevant to climate. The TSI is directly measured from space. Taking the value as 1367 Wm−2 and dividing by the geometrical factor four, this measurement gives global annual mean incident solar flux, with value close to 342 Wm−2. Global mean incident solar flux varies with Earth–Sun distance, between approximately 354 Wm−2 at perihelion (January) and 330 Wm−2 at aphelion (July). Instantaneous local TOA values vary between zero and the TSI, depending on latitude, date and local solar time.

The other global mean TOA radiation budget elements – reflected SW irradiance, emitted LW irradiance (or outgoing longwave radiation – OLR) – are not observed directly but rather constructed by averaging and adjusting instantaneous measurements from space. Narrow-band radiances from the operational weather satellites have been used to estimate the broadband SW and LW irradiances, in particular in the NOAA OLR products. With only IR window radiances, this requires uncertain spectral corrections, but Ellingson and others (Ellingson et al., 1989; Lee et al., 2007) have used additional narrow-band (HIRS) radiances to produce an improved OLR (broad-band LW) dataset. Using the Meteosat infrared window and “water-vapor” channels, Cheruy et al., 1991 estimated broad-band OLR from Meteosat data; Ba et al., 2003 used GOES sounder radiances to determine OLR. Li and Trishchenko, 1999 examined the relation between narrow-band visible and broad-band SW radiances and irradiances.

Satellite missions dedicated to ERB determination (Table 1) have mostly used broad-band channels, often using spectral subtraction of a SW channel (obtained with a fused silica filter) from an unfiltered (total or TW) channel to determine LW (ir)radiance. Most ERB instruments have relatively flat SW spectral response (Fig. 2), so that filtering errors in estimating true broad-band SW are much smaller than when only a narrow-band visible channel is used (Table 2). No truly broad-band LW filter exists, and the ERBE scanner LW products depend more on the spectral subtraction procedure than on the measurements using the diamond LW filter. Spectral subtraction does, however, make the daytime LW products sensitive to the SW calibration (Thomas et al., 1995).

Sommaire des données disponibles du bilan radiatif. La colonne 5 donne soit l’heure locale solaire du nœud ascendant (LTAN) pour les orbites héliosynchrones, soit la période de précession (PP) pour les orbites dérivantes. La colonne 6 donne la période de fonctionnement du satellite.

| Mission | Satellite | Inclination (°) | Orbit type | LTAN or PP* | Period of operation |

| ERBE | ERBS | 57 | Precessing | 72 days | Non-Scanner Nov 1984–1999 |

| Scanner Nov 1984–Feb 1990 | |||||

| NOAA-9 | 99 | Sun-synchronous | 15:00 | Mar 1985–Jan 1987 | |

| NOAA-10 | 99 | Sun-synchronous | 19:30 | Dec 1986–May 1989 | |

| ScaRaB | Meteor-3/7 | 82 | Precessing | 209 days | Feb 1994–Mar 1995 |

| Resurs-0 | 99 | Sun-synchronous | 22:00 | Nov 1998- Mar 1999 | |

| CERES | TRMM | 35 | Precessing | 50 days | Dec 1997–Sept 1998 |

| Terra FM1, 2 | 99 | Sun-synchronous | 22:30 | Mar 2000–… | |

| Aqua FM3, 4 | 99 | Sun-synchronous | 13:30 | July 2002–… | |

| GERB | Meteosat-8 | 0 | Geo-stationary | From December 2002 | |

| Meteosat-8 | 0 | From December 2005 |

Broad-band SW spectral response. Relative spectral responses of the SW channel of ScaRaB-2 (blue), and comparison with those of GERB-2 (green), ERBE (red) and CERES (black). All are normalized to 1 at 2 μm. Data Origin: http://ggsps.rl.ac.uk/information.html#Spectral for GERB and (Loeb et al., 2000) for CERES.

Réponse spectrale SW (ondes courtes) à bande large. Réponse spectrale relative pour le canal SW de ScaRaB-2 (bleu) comparée à celles de GERB-2 (vert), ERBE (rouge), et CERES (noir). Toutes sont normalisées à la valeur 1 à 2 μm. Source : http://ggsps.rl.ac.uk/information.html#Spectral pour GERB et (Loeb et al., 2000) pour CERES.

Facteurs de filtrage SW et erreurs spectrales pour différents instruments BRT. La dernière ligne donne l’équivalent pour une bande spectrale étroite dans le visible (0,5–0,7 μm). Pour que la comparaison soit significative, on a utilisé la même base de données de signatures spectrales terrestres dans tous les cas, et les réponses spectrales instrumentales ont été normalisées de la même façon (facteur de filtrage 1 pour un corps noir à 5800 K).

| Filtering Factor × 100 | Spectral Errors Wm−2 | |||

| Max–Min | rms | Max–Min | rms | |

| ScaRaB-2 | 6.43 | 1.03 | 7.28 | 1.03 |

| ERBE/ERBS | 9.64 | 1.53 | 10.02 | 1.93 |

| CERES/TRMM | 11.08 | 1.73 | 19.77 | 4.23 |

| GERB-2 | 15.19 | 2.48 | 22.58 | 3.94 |

| VIS Narrow Band | 93.29 | 16.32 | 117.78 | 22.20 |

Some instruments (e.g. the wide-field-of-view or WFOV instruments on ERBE, (Barkstrom, 1984)) provide direct measurements of irradiances directly at satellite altitude, these corresponding to spatial resolution of a few thousand km at TOA. Estimating irradiances at TOA, nevertheless, requires “inversion” (Smith et al., 1986). With scanners or other narrow-field-of-view (NFOV) instruments, TOA spatial resolution can be finer than 30 km, allowing discrimination by surface scene and cloud cover, but it is essentially radiances that are measured. In either case, the construction of spatial (regional, zonal, global) and temporal (daily, monthly, annual) mean TOA fluxes (irradiances) requires taking into account issues of calibration and spectral coverage, anisotropy of the outgoing radiances fields (especially reflected SW), diurnal and meteorological variation, and angular and time sampling. These have been reviewed in some detail (cf. e.g. (Kandel, 1990; Kandel and Viollier, 2005; Stephens et al., 1981)). Section 3.1 below presents the results for the global annual mean TOA ERB.

Beginning with the Nimbus-6 and 7 ERB missions (cf. (House et al., 1986; Jacobowitz et al., 1984)), and continuing with ERBE and CERES, rotating azimuth scanners have provided multiple, nearly simultaneous views of Earth targets, and the accumulating data on anisotropy have been used to derive angular distribution models (ADMs: (Smith et al., 1986; Suttles et al., 1988a, 1988b)) for a variety of scene types. In ERBE processing (and “ERBE-like” processing for ScaRaB and CERES), scene identification (and in particular, cloud cover characterization) relies only on broad-band (SW and LW) measurements. Advanced CERES products use scene identification based on the narrow-band radiances available with finer spatial resolution from the MODIS instrument. The methods used have been progressively refined since ERBE, on the basis of accumulating data on the anisotropy and diurnal variations for which corrections must be made, with instruments in both sun-synchronous and precessing orbits (Barkstrom et al., 1989; Brooks et al., 1986; Chang et al., 2000; Haeffelin et al., 1999; Haeffelin et al., 2001; Kandel et al., 1998; Loeb et al., 2003a, 2003b, 2007a,b; Rieland and Raschke, 1991; Smith et al., 1986; Standfuss et al., 2001; Suttles et al., 1988a, 1988b; Viollier et al., 2004; Wielicki et al., 1996, 1998; Young et al., 1998).

Availability of narrow-band channels has improved or provided alternative scene identification procedures on ScaRaB and CERES (Stubenrauch et al., 1993). In rotating azimuth mode, one of the CERES scanners has provided multiple views of Earth targets, as has the POLDER instrument (Buriez et al., 2007). On the planned ESA-JAXA EarthCARE (Cloud-Aerosol-Radiation Explorer) mission, the broad-band radiometer (BBR) is designed with the same objective. In addition, the Geostationary Earth Radiation Budget instrument (GERB) flying on Meteosat-8 since late 2002 has continuous but geographically limited coverage (Harries and Crommelynck, 2000; Harries et al., 2005), and so provides complete time and solar angle sampling at the expense of viewing angle sampling.

Alternative approaches to ERB determination from space use satellite retrievals of cloud and atmospheric properties (including aerosol layers), generally on the basis of observations in narrow spectral bands, together with radiative transfer calculations. In particular, this has been done with the ISCCP cloud products (Rossow and Schiffer, 1991; Rossow et al., 1996; Zhang et al., 2004, 2007) together with retrieved atmospheric temperature and humidity fields. This yields not only the TOA radiation fields, but also upward and downward SW and LW irradiances at the surface and at different levels in the atmosphere. Analogous methods have been applied in the CERES framework using the MODIS (moderate-resolution imaging spectrometer) radiances together with the broad-band CERES scanner radiances (Charlock et al., 1997; Kato et al., 2005).

Forward radiative transfer calculations can be applied to analyzed temperature-humidity-aerosol fields (together with surface properties) to obtain the TOA ERB (Allan et al., 2004, 2005). They can also yield SW and LW radiances (and indeed spectra) emerging from the atmosphere in any direction, and these synthesized values can be compared directly with satellite narrow-band or broad-band radiance measurements without using the angular corrections needed to transform them into TOA fluxes (Morcrette, 1991; Ringer et al., 2003; Roca et al., 1997; Slingo et al., 2003). Moreover, radiation measurements, narrow- or broad-band, in any direction at the surface or indeed at any atmospheric level can similarly be synthesized.

The strong effects of clouds on the Earth's Radiation Budget (particularly but not only in the SW domain) can be parameterized by the quantity “cloud radiative forcing” (Charlock and Ramanathan, 1985) corresponding to the changes in the SW and LW radiation fields computed with and without cloud opacity but with no other changes in atmospheric temperature-humidity structure. Beginning with ERBE, observational estimates of SW and LW cloud-radiative forcing (CRF) have been made comparing outgoing SW and LW fluxes averaged over pixels identified as cloud-free with the all-sky averages of fluxes in the same geographical regions (Fouquart et al., 1990; Ramanathan et al., 1989). Of course, the representativity of observational CRF determinations is particularly sensitive to the accuracy of identification of cloud-free scenes as well as to the angular and temporal sampling deficiencies that can bias the flux determinations. Nevertheless, observational estimates of SW and LW CRF have proved to be powerful tools in the in-validation of climate models, i.e. in identifying those models that obtain TOA ERB in agreement with observations by compensating errors in cloud effects.

3 Global and regional means and the annual cycle of TOA ERB

3.1 Global annual means

The last pre-satellite estimate (London, 1957) of the TOA ERB gave Earth's Bond albedo as 0.36, somewhat lower than Danjon's earthshine-based estimate of 0.42. Regarding emitted LW flux, the study essentially assumed zero global net radiation. The very first measurements from space of both reflected SW and emitted LW radiation, with the radiometer designed by Suomi and Parent flown in 1959 on the Explorer-7 satellite, quantified the strong effects of clouds and showed that global mean albedo was close to 0.30. The Nimbus missions (Jacobowitz et al., 1984; Raschke et al., 1973; Stephens et al., 1981) confirmed this result, as did results from ERBE (Barkstrom et al., 1989). Comparing ERBE and earlier determinations, Kiehl and Trenberth (1997) judge that the ERBE outgoing LW flux determination of 235 Wm −2 for the global annual mean is robust. Considering the significant uncertainties (calibration, anisotropy, diurnal variation) affecting the determination of reflected SW flux, and noting that TOA net flux must be less than +1 Wm−2, they assume a positive bias in the reflected SW and adjust it to 107 Wm−2, corresponding to global albedo 0.31 for TSI = 1367 Wm−2. The measurements by ScaRaB (Duvel et al., 2001; Kandel et al., 1998) and CERES give very similar global mean values. The extent to which ERBE and CERES products can be adjusted to consistency has been examined recently (Loeb et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 2009).

Using CERES data from March 2000 to February 2004, Kato (2009) gives global annual mean TOA reflected solar SW flux 97.0 Wm−2 and TOA emitted LW flux 239 Wm−2. Assuming TSI of 1366 Wm−2, i.e. global annual mean incident solar flux 341.5 Wm−2, he finds 0.284 for Earth's Bond albedo, a value slightly lower than earlier determinations. The corresponding global radiation balance (net flux) is excessive at +5.5 Wm−2. Indeed, Loeb et al., 2009 find a net flux of +6.5 Wm−2, and discuss the possible sources of error that can explain this discrepancy. Table 3 compares different determinations. In this table, the ERBE results correspond to the period from February 1985 to January 1989; ScaRaB results are for the period from March 1994 to February 1995, but with October missing. Three slightly different sets of CERES products are given, all for the period from March 2000 to February 2005. For each case, we compare results for albedo and global radiation balance, assuming two slightly different values of solar irradiance.

Bilan radiatif de la Terre au sommet de l’atmosphère (moyenne globale annuelle), Ici les données ERBE pour les 4 années de février 1985 à janvier 1989. La période ScaRaB (Meteor) comprend 11 mois (mars 1994–février 1995, sauf pour octobre). Tous les produits CERES donnés ici correspondent aux 5 années de mars 2000 à février 2005. Le produit ES4 est obtenu par traitement similaire au traitement ERBE ; le produit SRBAVG utilise des améliorations dans les corrections angulaires et diurnes. La dernière ligne suit l’ajustement (Loeb et al., 2009) donnant un rayonnement net ou bilan radiatif global, égal au résultat obtenu par modélisation (Hansen et al., 2005) pour une constante solaire de 1360 Wm−2. Les colonnes à droite montrent l’influence sur l’albedo et le bilan radiatif au sommet de l’atmosphère, lorsqu’on utilise une valeur différente pour l’irradiance solaire.

| Global Annual Means | TOA Flux (Wm−2) | Solar Irradiance (Wm−2) | ||||

| 1368 | 1360 | |||||

| Emitted LW Flux | Reflected SW Flux | Albedo (%) | Net Wm−2 | Albedo (%) | Net Wm−2 | |

| ERBE | 235.2 | 101.2 | 29.6 | +5.6 | 29.8 | +3.6 |

| ScaRaB | 237.3 | 102.3 | 29.9 | +2.4 | 30.1 | +0.4 |

| CERES-ES4 | 239.0 | 98.3 | 28.7 | +4.7 | 28.9 | +2.7 |

| CERES-SRBAVG | 237.1 | 97.7 | 28.6 | +7.2 | 28.7 | +5.2 |

| CERES-SRBAVG (adjusted) | 239.6 | 99.5 | 29.1 | +2.9 | 29.3 | +0.9 |

3.2 Cloud radiative forcing

Consistent results have also been obtained since ERBE (and retrospectively since Nimbus-7/ERB; cf. (Ardanuy et al., 1991)) for global mean cloud radiative forcing, with SW CRF close to –50 Wm−2, LW CRF close to +20 Wm−2, net CRF close to –30 Wm−2 (Kato et al., 2008). These values are of the same order as the radiative forcings identified with water vapor, carbon dioxide, and ozone (Kiehl and Trenberth, 1997): H2O accounts for 75 Wm−2 of LW absorption and 43 Wm−2 of SW in the clear atmosphere, CO2 for 32 Wm−2 (LW), and O3 for 14 Wm−2 (SW) and 10 Wm−2 (LW). These climate forcings should be confused neither with the climate change forcing corresponding to anthropogenic increase of atmospheric CO2 and other well-mixed greenhouse gases, nor with the feedbacks associated with changes in atmospheric water vapor content and cloud as climate warms.

3.3 Zonal and regional mean TOA ERB elements

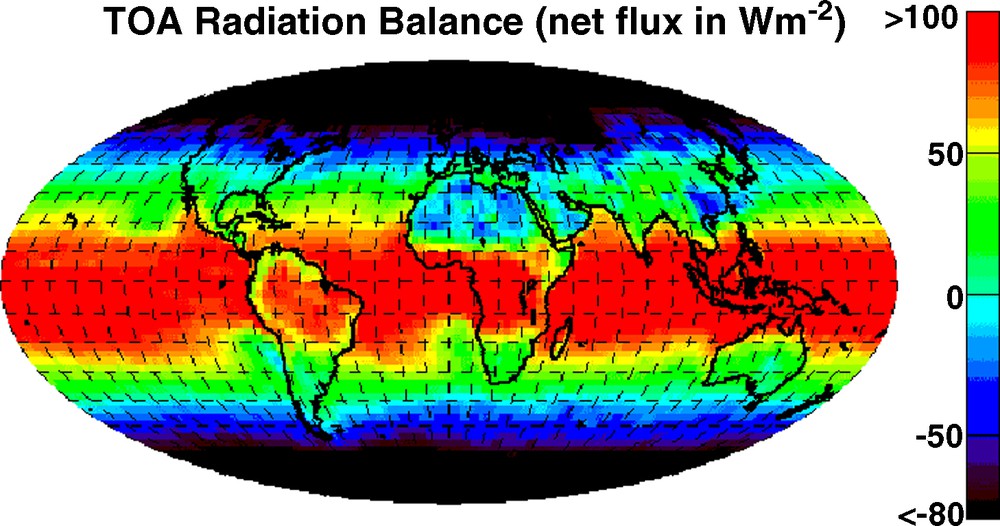

Measurements made in the 1960s from the Tiros-4 and ESSA-3 satellites gave, in addition to the global annual mean TOA ERB elements, both the variation with latitude of the annual means and the annual cycle of the global means. With subsequent missions, data accumulated on the space–time distribution of the TOA ERB elements. The quantification by Nimbus-3 (Raschke et al., 1973) of the slightly negative annual mean radiation balance above the Sahara was an important factor in the Charney hypothesis (Charney, 1975) regarding drought and desertification in the Sahel. The regional and monthly mean ERBE products – reflected SW, emitted LW, and net radiation fluxes (Figs. 3 and 4) at TOA as well as SW and LW CRF – provided on a 2.5°×2.5° latitude–longitude grid, confirmed the overall geographical structure determined earlier, while exhibiting significant but unsurprising year-to-year changes, in particular those related to ENSO variations. ScaRaB-Resurs observed strong LW anomalies related to the 1999 La Niña event (Duvel et al., 2001). More generally, regional flux anomalies reach ±15 to 20 Wm−2.

TOA radiation balance (net flux in Wm−2) for March. Average of ERBE, ScaRaB and CERES data products. In this equinox month, the heating zone is centered on the equator with maxima around +90 Wm−2. Net flux is systematically negative at high latitudes. At low latitudes around the Tropics, negative or weakly positive values are observed over deserts (Sahara, Arabia), and also in low-cloud areas over eastern China as well as over the subtropical anticyclone ocean areas west of South America and southern Africa. Masquer

TOA radiation balance (net flux in Wm−2) for March. Average of ERBE, ScaRaB and CERES data products. In this equinox month, the heating zone is centered on the equator with maxima around +90 Wm−2. Net flux is systematically negative at ... Lire la suite

Bilan radiatif TOA (flux net au sommet de l’atmosphère, en Wm−2) pour mars. Produits ERBE, ScaRaB et CERES moyennés. Au cours de ce mois d’équinoxe, la zone de réchauffement se trouve centrée sur l’équateur, avec des maxima près de +90 Wm−2. Le flux net prend systématiquement des valeurs négatives aux hautes latitudes. Aux basses latitudes autour des Tropiques, on observe des valeurs négatives ou faiblement positives au-dessus des déserts (Sahara, Arabie), ainsi que dans les régions à nuages bas, tant sur l’Est de la Chine que dans les anticyclones des régions océaniques subtropicales à l’ouest de l’Amérique du Sud et de l’Afrique australe. Masquer

Bilan radiatif TOA (flux net au sommet de l’atmosphère, en Wm−2) pour mars. Produits ERBE, ScaRaB et CERES moyennés. Au cours de ce mois d’équinoxe, la zone de réchauffement se trouve centrée sur l’équateur, avec des maxima près de +90 Wm−2. ... Lire la suite

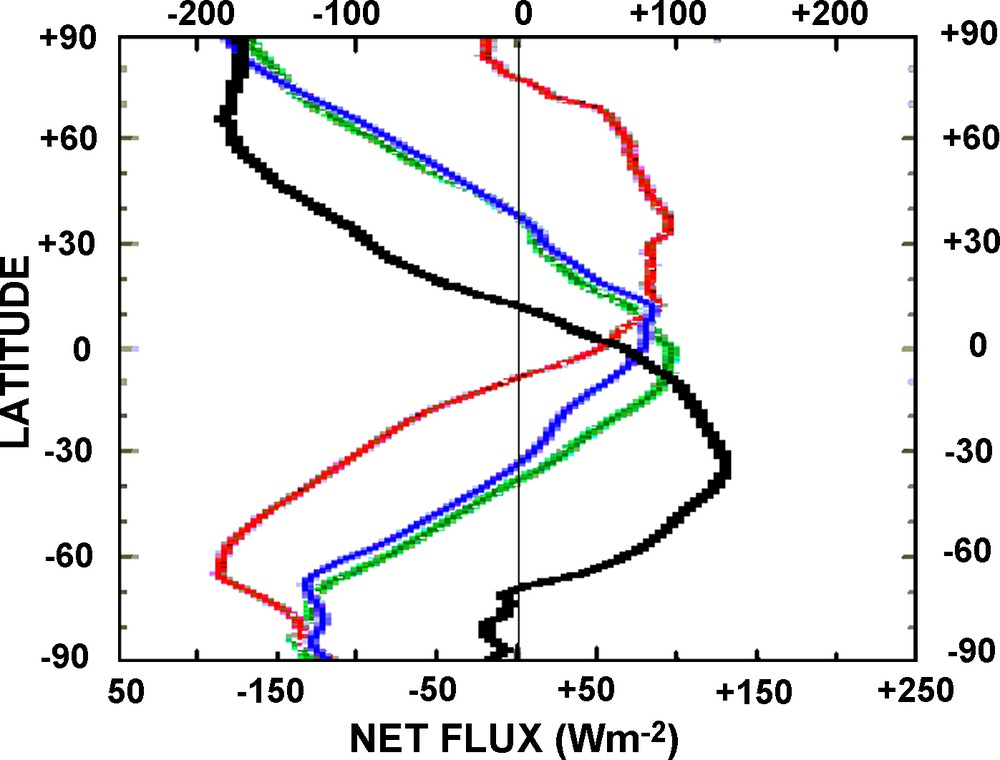

Zonal mean TOA radiation balance. CERES EBAF 5-year mean values (Terra based, adjusted) for March (green), June (red), September (blue), and December (black).

Bilan radiatif TOA – moyenne zonales. Valeurs des produits CERES EBAF moyennés sur 5 ans (basées sur CERES/Terra et ajustées) pour mars (vert), juin (rouge), septembre (bleu) et décembre (noir).

For zonal means, the ERBE (1985–89) and ScaRaB (1994–95 and 1998–99) records show departures of individual monthly zonal means from multi-year averages for the same months and zones generally smaller than 10 Wm−2, except for reflected SW in polar summer months for which departures reach 20 Wm−2 (Kandel et al., 1998: Fig. 7). The ERBE (1985–89) and CERES (March 2000 – May 2004) zonal annual means are very close, with zonal albedo slightly smaller for CERES than for ERBE except near the poles; annual zonal mean outgoing LW radiation fluxes are identical except for tropical latitudes south of the intertropical convergence zone (between 10°N and 20°S), where the values for the CERES period are slightly larger (Fasullo and Trenberth, 2008b). The equator-to-pole gradient of TOA net radiation zonal means constitute an important tool for determining meridional atmospheric and oceanic heat fluxes.

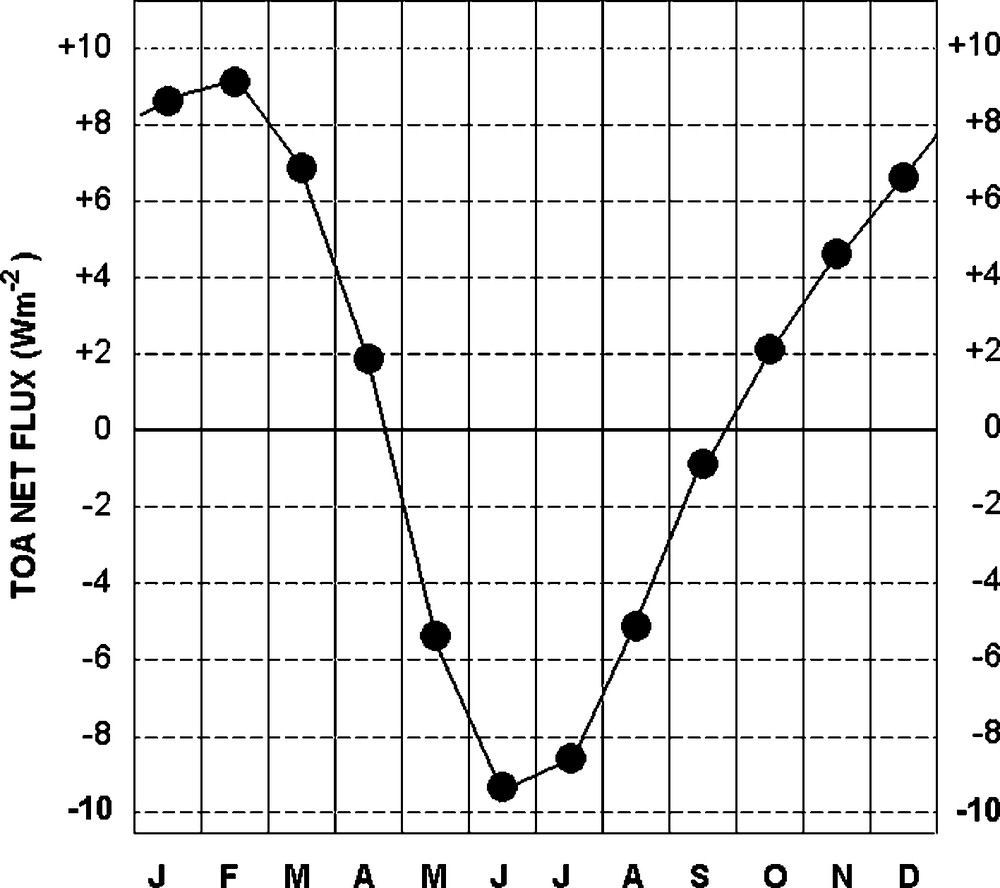

3.4 The annual cycle of TOA ERB

Early ERB missions (Ellis et al., 1978) gave the essential features of the annual cycle of TOA ERB, reproduced with higher accuracy in modern determinations (Duvel et al., 2001; Fasullo and Trenberth, 2008a, 2008b; Kandel and Viollier, 2005; Ramanathan et al., 1989). Global annual mean TOA radiation balance is probably approaching +1 Wm−2 in 2008, although beginning in 1985, ERBE, ScaRaB, and CERES gave values ranging from +2 to +6 Wm−2, all of these values lying within a range defined by (mostly SW) absolute calibration and radiance-to-flux conversion uncertainties ((Fasullo and Trenberth, 2008a: Table 1). However, the non-negligible year-to-year differences in absolute level of the global reflected SW and outgoing LW radiation fluxes largely cancel in the net radiation. As a result, the annual cycle of global radiation balance (Fig. 5) is very well defined (cf. (Kandel and Viollier, 2005: Fig. 3d)), with a significantly positive maximum in February (i.e. a month after perihelion) approximately 20 Wm−2 higher than the negative minimum in June-July, near aphelion. This corresponds mostly to the annual cycle of incident solar flux commanded by the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit. However, global mean OLR has a significant though small maximum in Northern Hemisphere summer (10 Wm−2 higher than minimum), while reflected SW goes through a well defined minimum in August, approximately 15 Wm−2 lower than the November–February minimum. The north–south dissymmetry of continents thus also plays a significant role.

Annual cycle of global (TOA) radiation balance. CERES EBAF 5-year mean values (Terra based, adjusted).

Cycle annuel du bilan radiatif planétaire (TOA). Valeurs des produits CERES EBAF moyennés sur 5 ans (basées sur CERES/Terra et ajustées).

The annual cycle of TOA cloud radiative forcing has been analyzed since ERBE, and in particular using the 2000–2004 CERES results (Kato et al., 2008). Zonal mean LW CRF varies between 0 and +50 Wm−2, with a seasonally shifting peak in the intertropical convergence zone, and with relatively little annual variation in the secondary maxima in the subtropical and lower mid-latitude zones, in the minima at the poles, and in the relatively clear tropical zones. There is of course a strong annual cycle in zonal mean SW CRF, which ranges from 0 (at the South Pole) to strongly negative values in the midlatitudes (−130 Wm−2 at 50°S in southern summer; −90 Wm−2 at midlatitudes north and south from September to November), and less strongly negative values from March to August, again revealing the role of the distribution of continents. At solstice, net CRF, strongly negative at most latitudes in the summer hemisphere, becomes positive poleward of 30° latitude in the winter hemisphere (Fig. 6). This change of sign must be taken into account when estimating possible effects on cloud radiative forcing of solar or cosmic-ray particles strongest at high latitudes. Similarly, one must consider the strong variation with altitude of cloud contributions to radiative forcing.

Zonal mean net cloud radiative forcing. CERES EBAF 5-year mean values (Terra based, adjusted) for March (green), June (red), September (blue), and December (black).

Forçage radiatif de la nébulosité - cycle annuel des moyennes zonales. Valeurs des produits CERES EBAF moyennés sur 5 ans (basées sur CERES/Terra et ajustées) pour mars (vert), juin (rouge), septembre (bleu) et décembre (noir).

4 Surface and atmospheric radiation and energy budgets

Direct measurements of SW and LW radiation at the surface exist, but with poor coverage of the globe, extremely sparse for ocean. Coverage by the well-calibrated instruments of the Baseline Surface Radiation Network (BSRN: (Ohmura et al., 1998)) remains limited, in particular with regard to ocean areas constituting well over half of the surface of the globe. Direct measurements in the atmosphere depend on airborne or balloon-borne instruments, with even sparser coverage and generally with no continuity in time. With observation from space, coverage is truly global, and continuous monitoring is possible. However, the surface and in-atmosphere radiation budget products obtained using observations from space are different in nature from the TOA ERB products based on direct measurements involving only corrections for sampling, especially angular and time sampling.

Thus, whereas TOA ERB is extremely well determined, significant uncertainties remain in estimates of surface and in-atmosphere radiation budgets, and to these estimates correspond significant uncertainties in the non-radiative components of the surface and atmospheric energy budgets. A major issue is the question of completeness of satellite-based sounding of atmospheric properties, especially in regions of optically thick cloud cover.

Radiative flux divergence is defined as the net radiation into a level. Surface radiative flux divergence is therefore the downwelling minus the upwelling radiation fluxes at the surface, as given in Eq. (4) in Section 1. The TOA radiative flux divergence corresponds to the net radiation into the Earth system (Eq. (1)). The atmospheric divergence is defined by subtracting the surface from the TOA divergence (Eq. (6)). Positive or negative values imply respectively radiative heating and cooling; as noted earlier, surface and atmospheric heating/cooling also depend on non-radiative energy fluxes. These measurements serve first to compare observations and models. Estimates of global mean surface radiation (cf. Eq. (4)) ranged from 142 to 174 Wm−2 for net downward shortwave and from 40 to 72 Wm−2 for net upward longwave fluxes ((Kiehl and Trenberth, 1997: Table 1)). Estimates of SW radiation absorbed in the atmosphere ranged from 65 to 89 Wm−2, with similar large uncertainties in the nonradiative heat fluxes from surface to atmosphere.

Narrow-band ISCCP and MODIS as well as broad-band CERES data have been used to estimate surface radiation fluxes using a variety of techniques (Pinker et al., 2005; Wielicki et al., 1996). The CERES estimates compare well with measurements made at the surface at the Papua New Guinea, Barrow Alaska, and the Southern Great Plains sites (Kato et al., 2008). With distinction of clear-sky and all-sky radiation fluxes, the CERES products yield the cloud effects on the atmospheric radiation budget, dominated (at least in the zonal mean) by the longwave effect, with the meridional gradient providing an important constraint on atmospheric dynamics (Kato et al., 2008).

Local long-time series of surface fluxes are derived with similar or innovative methods using data from geostationary satellites, for example from Meteosat (Rigollier et al., 2004) (ESA Satellite Application Facility on Climate Monitoring). At global scale, the more recent estimates of the atmospheric absorption suggest that the atmosphere is more absorbing than its model representations. The data directly measured at surface stations (mainly continental) have thus been analyzed and compared with surface fluxes calculated using general circulation models (Wild et al., 2006) or applying forward radiative transfer to analyzed atmospheric temperature-humidity fields. As for long-term variability, any significant trends have important implications for the water cycle (Wild et al., 2004). However, although downward solar radiation at the Earth's surface (also called ‘global dimming’) declined between 1960 and 1990, this trend has since been reversed (Murphy et al., 2009; Wild et al., 2005).

Airborne as well as surface and satellite measurements of solar flux have often given results in disagreement with model computations of the transfer of shortwave radiation in the atmosphere, especially but not only in the cloudy atmosphere (Cess et al., 1995; Kaufman et al., 2002; Pilewskie and Valero, 1995; Pope et al., 2002; Ramanathan et al., 1995). Thus, although TOA ERB determinations from satellite observations have converged, significant contradictions have remained in estimates of in-atmosphere and surface SW fluxes, raising the question of the existence of unidentified excess or “anomalous” absorption. This would have significant implication for climate model results (Ramanathan et al., 1995). However, careful analysis of more complete observations shows that the anomaly is largely an artefact (Li, 2004; Ramana et al., 2007). Consideration of three-dimensional effects is essential. In the case of deep convective cloud, for example, bias in scene albedo can reach 46% when the Sun is low (Di Giuseppe and Tompkins, 2005).

Observations from space remain essential for determination of atmospheric flux divergence using surface and airborne data obtained at important surface stations such as the Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) program facility in the Southern Great Plains, and in the course of intensive field operations. For the African Monsoon Multidisciplinary Analysis (AMMA) field campaign, the ARM Mobile Facility was deployed in Niamey (Niger) to measure radiative fluxes at the surface and to sound the atmospheric structure above the site (Miller and Slingo, 2007). As part of the project to determine Radiative Atmospheric Divergence using the ARM mobile facility, GERB data and the AMMA Station (RADAGAST), TOA flux estimates were combined with surface data so as to calculate radiative flux divergence through the atmosphere. Among important RADAGAST operations was the study of the dust storm beginning 5 March 2006. Comparisons between observed and modeled SW divergence suggest that radiation codes used in models underestimate the observed SW absorption in the dusty atmosphere (Slingo et al., 2006). Also, over the whole year (2006) in Niamey, LW divergence was shown to be independent of column water vapor.

5 Interannual variations of the ERB

For the detection of trends (or significant inter-annual variations) from ERB data as from most remote sensing data, absolute radiometric calibration and gain stability are particularly problematic in that gain variations can be misinterpreted as trends in the atmospheric or surface properties. Similarly, shifting observing times for nominally but never perfectly sun-synchronous satellites can produce spurious trends in time-averaged ERB, depending on the diurnal averaging procedure (Rieland and Raschke, 1991; Standfuss et al., 2001; Young et al., 1998); the same holds for other important satellite data products (Evan et al., 2006; Klein and Hartmann, 1993). Nevertheless, there is considerable interest in monitoring temporal variations and detecting trends of the ERB related to anthropogenic and natural climate change, even though, apart from solar variations, separation of the “external” change forcing factors (e.g. CO2 added to the atmosphere, land surface modification independent of climate change) from the atmospheric and surface feedbacks is often difficult if not impossible.

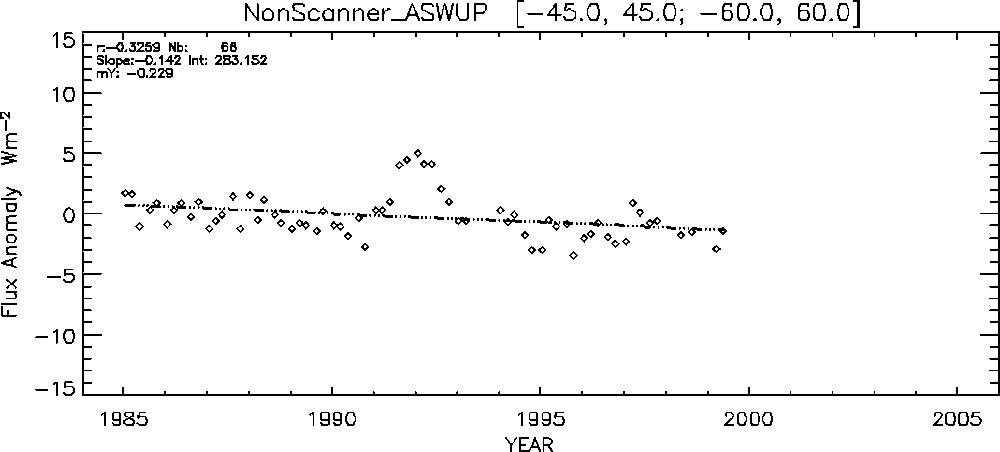

On the basis of ERBE, ScaRaB, and CERES data, (Wang et al., 2002; Wielicki et al., 2002) reported large decadal changes in tropical mean (20°N to 20°S) ERB between the 1980s and the 1990s. These results were re-examined several times both for calibration issues and altitude correction. With these corrections applied in particular to the ERBS nonscanner WFOV observations, changes in tropical mean LW, SW, and net radiation between the 1980 s and the 1990 s now stand at 0.7/−2.1/1.4 Wm−2, respectively (Wong et al., 2006: Fig. 7). The decadal variations and trends are at the limit of detectability. The impact of the calibration uncertainty can be minimized by intercomparing several data sources and focusing on local anomalies in the trends. Over a part of the Southeast Atlantic including the marine low cloud area off Angola, there appears a decrease of the yearly means of net flux estimated at 2.2, 3 and 6 Wm−2 respectively for three different datasets. A different method (2006) shows strong correlation between observed interannual variability of near-global ERBS net radiation and the ocean heat storage record (Wong et al., 2006). Both datasets show variations of roughly 1.5 Wm−2 in planetary net heat balance during the 1990s.

Evolution of the SW monthly flux anomaly based on the ERBE Nonscanner (Edition 3 Revision 1) series averaged over Africa and the surrounding oceans (45°S–45°N/60°W–60°E). On both this and the corresponding ISCCP-FD series a significantly positive (+5 Wm−2) reflected SW anomaly is observed in 1991-92 following the Pinatubo eruption. Except for this event, the general trend is slightly negative (Wong et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007).

Évolution de l’anomalie mensuelle du flux SW réfléchi, basé sur la série des produits ERBE à champ fixe (Édition 3 Révision 1) moyennés sur l’Afrique et les océans voisins (45°S-45°N/60°W-60°E). Sur cette série, comme sur la série correspondante ISCCP-FD, on observe une anomalie positive significative (+5 Wm−2) en 1991-1992, à la suite de l’éruption du mont Pinatubo. À part cet événement, la tendance générale est faiblement négative (Wong et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2007).

Although any long-term trend in TOA ERB has been below the level of detectability, other interannual variations, in particular those linked to ENSO on the one hand (Ringer, 1997) and volcanic eruptions on the other, have appeared clearly. During the strong 1997-98 El Niño, outgoing TOA LW flux in the tropical zone exhibited a strong (+5 Wm−2) anomaly between February and May 1998, observed by the CERES instrument on board TRMM (cf. (Allan and Slingo, 2002; Allan et al., 2002; Kandel and Viollier, 2005: Fig. 5). Considering the CERES data for 2000 to 2005, a significant anomaly of reflected SW radiation appears over land areas but not over ocean in the tropical zone, anti-correlated with ENSO in 2002-2003 (Loeb et al., 2007b: Fig. 7)

Powerful volcanic eruptions such as that of Mount Pinatubo lead to production of stratospheric aerosols with a significant increase in global albedo (Fig. 7; (Minnis et al., 1993)), and reduction of solar radiation reaching the troposphere and surface. The changes in the SW radiation field can for the most part be taken as external forcing. However, for the LW radiation field, the effects of the resulting cooling of troposphere and surface, with observed reduction of absolute humidity (Soden et al., 2002), must be taken as feedback, as must any SW effects of resulting changes in cloud cover.

Limiting analysis to CERES Terra data products for the relatively undisturbed period from March 2000 through February 2004 (Kato, 2009), only small variation appears in global annual means: 0.4% difference between maximum and minimum values of TOA reflected SW, 0.1% in outgoing LW irradiance. Considering the geographical distribution of variability (monthly anomalies) with 1°×1° regions, and distinguishing all-sky and clear-sky irradiances, clouds increase standard deviation by a factor two, but with significant anti-correlation between SW and LW anomalies, so that variability of the TOA radiation balance is smaller.

6 Discussion; priorities for future research

Pursuit and improvement of space-based observations are essential; observation strategy has been discussed in the WMO framework (Bizzari, 2007; Schulz, 2008). Considering only TOA ERB, detection of trends requires elimination of (time-dependent) biases arising from instrumental degradation (spectral response and calibration), changing incomplete angular sampling, and changing incomplete time sampling. This argues for future missions with multi-view capacity (as with CERES). In this respect, the CERES and MODIS instruments on Terra and Aqua (launched in 2000 and 2002 respectively) continue to work well. In the context of the National (USA) Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System (NPOESS, to replace the current American civil and military operational environmental satellite systems), CERES flight model 5 will be launched in 2010 on the NPP satellite (NPOESS Preparatory Project) satellite, in polar sun-synchronous orbit. Continuation of the CERES program is under consideration.

Absolute calibration must be improved; at the same time more work is needed to ensure the intercomparability, over the long term, of data obtained in the past (perhaps not so well calibrated) with future data. Assuming that the issue of the exact absolute value of the solar constant can soon be settled (Kopp et al., 2005), putting the ERB datasets going back to ERBE and perhaps Nimbus-7/ERB on the same absolute scale will still depend on the calibration of the Earth-viewing sensors. With a view to providing long-term “climate-accuracy” calibration for other solar and infrared space-borne sensors, NASA has selected a new climatic mission named CLARREO (Climate Absolute Radiance and Refractivity Observatory; see http://clarreo.larc.nasa.gov/). CLARREO will carry IR and UV/VIS/NIR interferometers with highly accurate absolute radiometric calibration. Three small satellites are planned, in true polar orbits (non-sun-synchronous) at 750 km altitude, with 60° angular shift from one another. The interferometers will view nadir with a field of view of about 100 km.

Apart from the problems of absolute calibration and correction for spectral filtering (Fig. 2, Table 2), there remain the difficult issues of changing biases related to changing sampling of viewing angles and times. Given the impossibility of sampling all outgoing directions, the application of angular distribution models remains essential, and this requires excellent scene (cloud cover) characterization, depending notably on narrow-band data with moderately high spatial resolution (Chang et al., 2000). To eliminate or at least to reduce time sampling bias, ERB processing now often uses data from geostationary satellites to monitor the diurnal cycle. Complete monitoring is possible with broad-band instruments flying on geostationary satellites. However, the GERB instrument on board Meteosat (Harries and Crommelynck, 2000; Harries et al., 2005) has serious deficiencies in spectral flatness over the broad-band shortwave domain because of the multiple reflections required by installation on this spinning satellite. This would not be the case on 3-axis stabilized satellites (cf. e.g. (Kandel et al., 1987)), on which broad-band spectral response could be closer to flat. An alternative would be to improve calibration of the narrow-band high-resolution operational channels on board geostationaries, and to compute broad-band radiances from these narrow-band data.

Radiation balance at TOA is systematically positive in the tropical zone, driving atmospheric and oceanic circulation. In this zone, with particularly strong effects of deep convective cloud and diurnal variation, broad-band ERB instruments have been deployed on low-inclination satellites so as to provide maximum coverage of the tropical region, drifting through all local times; specifically the NASA Earth Radiation Budget Satellite (ERBS) in ERBE and the (Japan-USA) Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission as part of CERES. Similarly, the joint French-Indian satellite Megha-Tropiques, with 20-degree inclined orbit, is to fly in the second half of 2010 (Roca et al., 2010).

Detection of intrinsic trends requires eliminating biases varying in the medium or long term, and this requires careful correction for imperfect spectral sensitivity as well as incomplete sampling of viewing and solar angles and diurnal variation. All of these corrections depend on good characterization of the scene, in particular with regard to cloud cover. These are difficult and expensive if not impossible to obtain from observing platforms far in space. Strong sampling considerations argue against observations from a site on the Moon's surface (Kandel, 1994). These also apply to earthshine data, in any event subject to atmospheric spectral filtering, even if a network of observatories can improve geographical sampling.

The even more remote Lagrange L-1 point has also been suggested as an appropriate site in space for observing the Earth's reflected solar radiation (the DSCOVER project: (Minnis et al., 2001; Valero and Charlson, 2008)); such a platform continuously observes practically all sunlit points of the planet. However, these observations all correspond to outgoing directions very close to backscatter, and so the radiance-to-flux conversion depends critically on the accuracy of this particular point of the bidirectional reflectance distribution. Thus, the perfect time sampling (also available from a full set of geostationaries) is obtained at the expense of extremely restricted angular sampling. Also, such a platform can never observe the night side, and so cannot monitor the full outgoing LW radiation. Furthermore, observation with spatial resolution sufficiently fine to perform scene characterization adequate for reliable angular correction requires a large instrument at a distance of 1.5 million km. This is true even if “ERBE-like” 30-km resolution is judged adequate, because accurate angular correction depends on cloud altitude estimated using wavelengths in the 10–12 μm range; required instrument size becomes prohibitive if 1-km resolution is required.

For monitoring the surface and atmospheric components of the Earth Radiation Budget, validation of the satellite data products, all of which are indirect, requires a more complete set of surface observations, an extended BSRN, especially over oceans. Because of local meteorological effects, existing or new stations on large islands probably do not represent correctly the situation over open ocean far from any land. The oceanographic community has made enormous progress in developing ocean monitoring both at the surface and at depth using automatic devices. It should be possible to deploy accurate radiation instruments, preferably easy to operate and to maintain, on board large stable ocean-going vessels such as supertankers. Even though this would not provide global ocean coverage, and would be subject to fair-weather bias, it would be a vast improvement over the current situation.

Climate change depends on what happens at the surface and in the atmosphere, and radiation there is not directly measurable from space. Global coverage is however only possible from space, and accurate determination of the atmospheric and surface radiation budgets requires narrow-band as well as broad-band observations from space. Characterizing the vertical profiles of radiation fluxes depends notably on synergy between passive and active instruments, providing vertical sounding of cloud and aerosol layers, as in the European-Japanese EarthCARE (Cloud-Aerosol-Radiation Explorer) project (Bézy et al., 2005; Doménech et al., 2007; Gelsthorpe et al., 2008; Kandel et al., 2003).

Cloud-radiation feedback by low clouds over subtropical and tropical oceans has been identified (Bony and Dufresne, 2005; Dufresne and Bony, 2008) as the critical uncertainty in estimating climate sensitivity to external forcing. Trenberth and Fasullo (Trenberth and Fasullo, 2009) examine the average change in surface energy balance, critical for climate change, from a number of model simulations for the period 1950–2100. The average of the models indicates that although the enhanced greenhouse forcing as well as water-vapor feedback operate on the longwave radiation, cloud feedback with reduction in cloud cover leading to increased surface absorbed solar radiation comes out as the dominant factor in warming. At present, observations do not settle the cloud feedback issue. More generally, significant progress in determining radiation feedbacks critical for climate sensitivity depends on determining the Earth's radiation budget from the top of the atmosphere to the surface with spatial and temporal resolution sufficiently fine to distinguish between different processes. In this sense, an important axis of future research should be the acquisition and refinement of data providing stringent tests of estimates of forcings and modelling of feedbacks on the regional scale. Only by improving modelling of cloud processes can the range of estimates of climate sensitivity and the considerable uncertainties regarding changes in precipitation be narrowed. Such improvement is urgent both with respect to reinforcing arguments for reductions of greenhouse gas emissions, and for preparing adaptation to inevitable climate change. Indeed, good space-time resolution is also required for monitoring of global annual and a fortiori zonal and regional monthly mean ERB elements.

Although TOA ERB is in itself an insensitive indicator of surface warming driven by anthropogenic intensification of the greenhouse effect (e.g. (Kandel, 1999; Slingo and Webb, 1997)), the global TOA radiation balance is a measure of how the Earth climate system, not now in equilibrium, is adjusting to increasing anthropogenic forcing (Murphy et al., 2009). Although the modelled value of 0.85 Wm−2 (Hansen et al., 2005) still lies well within the uncertainty of un-adjusted observational estimates of global TOA radiation balance (Loeb et al., 2009), continuing observation, with improved absolute calibration and spectral/angular/diurnal correction, could make it possible to obtain, within a decade, an observed trend in this imbalance. Such an observation would constitute a severe test of consistency with measured ocean warming and would provide guide for improvement of models of the changing climate system. Considering the accelerating increase of atmospheric concentrations of radiatively active gases, and the fact that this is now the principal driver of global climate change, continuing observation of the Earth Radiation Budget is an essential part of efforts to evaluate climate models and to improve them as tools for projection.

Acknowledgements

We thank our many colleagues and visitors at LMD – too many to name – who took part in work with ERBE and CERES data, in designing and building the ScaRaB instrument and processing system, and most recently ScaRaB/Megha-Tropiques. We also thank our many colleagues at NASA, in particular at NASA Langley Research Center, who have played and continue to play an essential role in Earth Radiation Budget science. Finally, all of us in the ERB/climate community owe much to the stimulating influence of Tony Slingo, and we miss him. As Bruce Wielicki put it, “The energy in the room went up whenever he walked in.”