1 Introduction

Taxonomic investigations in different genera of Valerianaceae [1,2] made us aware of problematic intergeneric relationships within the tribe Valerianeae Höck [3–5], such as we attempted to progress in this way using molecular markers. The chloroplast intergene atpβ-rbcL (ca. 900 bp) has repeatedly proven its utility in the resolution of phylogenies above the genus level [6–9]; in addition, the existence of an international bank of sequences of this genomic region allows many and wide comparisons. For these reasons, we chose this intergene to investigate intergeneric relationships within the tribe Valerianeae Höck.

As soon as we began aligning sequences, we noted a large amount of insertion–deletion events (‘indels’), resulting from loss or gain of one bp to more than 300 bp segments in one or several species of this group. Results of this sort suggest that these evolutionary events are important in this region of the chloroplast genome of Valerianaceae. Phylogenetic inference encounters difficulties from indels: alignments are more uncertain, and parsimony methods are difficult to apply. Further, indels are often superimposed or combined with substitutions of nucleotides (transitions and transversions) among the studied species. So, many authors prefer to eliminate the zones affected by indels from their analyses, thus losing valuable information.

This situation prompted us to examine several ways of coding indels before submitting aligned sequences to phylogenetic analysis: three of current use (‘complete omission’; ‘missing data’; ‘fifth base’) and a fourth one recently proposed by V. Barriel [10].

This study presents an evaluation of the influence of these different methods on the results of parsimony analyses.

2 Materials and methods

The cpDNA sequenced zone corresponds to the intergene atpβ-rbcL and the adjacent initial 156 bp of the rbcL gene of 21 species belonging to four genera of the tribe Valerianeae. These genera (Centranthus DC., Fedia Gaertn., Valeriana L. and Valerianella Miller) cover the four constituent subtribes of Valerianeae [3,4] (cf. annex 1). Valeriana is represented by American as well as European species. In addition, Patrinia villosa Juss. (tribe Patrinieae Höck), was sequenced and used as outgroup after preliminary investigations showed it as sister group of Valerianeae. The identification and origin of the material is indicated in Table 1.

Origin of samples of 22 studied species, location of voucher specimens, and accession numbers of sequences

| Species and their abbreviations | Origin, Voucher specimen | Accession number |

| Centranthus calcitrapae (L.) Dufr. (Ctr-cal) | France, Hérault, La Gardiole Mount, Mathez 1032 – 1997 (MPU) | AF448570 |

| Centranthus lecoqii Jordan (Ctr-lec) | France, Hérault, près Saint-Guilhem le Désert, Mathez 1076 – 1997 (MPU) | AF448571 |

| Centranthus ruber DC. (Ctr-rub) | France, Jardin des Plantes, Montpellier (MPU) | AF448572 |

| Centranthus trinervis (Viv.) Béguinot (Ctr-tri) | France, Bot. Gard. Chévreloup (Corse du Sud, Bonifacio 1994, Fridlender) – 1998 (MPU) | AF448573 |

| Fedia cornucopiae (L.) Gaertn. (Fed-cor) | Spain, Andalousie, Serranía de Ronda, Navarro s.n. – 1999 (MPU) | AF448574 |

| Fedia graciliflora Fisch. & Meyer (Fed-gra) | France, Bot. Gard. – Montpellier (MPU) | AF448575 |

| Fedia pallescens (Maire) Mathez (Fed-pal) | Morocco, Mehdyia, El-Oualidi s.n. – 1998 (MPU) | AF448576 |

| Patrinia villosa Juss. (Pat-vil) | France, Jardin des Plantes, Paris | AF448577 |

| Valeriana albonervata Robinson ex Seaton (Val-alb) | USA, Missouri Bot. Gard. (Mexico, Tamaulipas, Barrie & Cowan 1400, 1985) – 1998 (MEXU, MO, TEX) | AF448578 |

| Valeriana apula Pourret (Val-apu) | France, Pyrénées Orientales, Nohèdes, Molina s.n. – 1994 | AF448579 |

| Valeriana bractescens (Hook.) Höck (Val-bra) | Venezuela, Mérida, Mucubají, Xena 1361 – 1995 (VEN) | AF448580 |

| Valeriana dioica L. (Val-dio) | France, Gard, vallon du Bonheur, Mathez & Raymundez s.n. – 1998 (MPU) | AF448581 |

| Valeriana laurifolia H.B.K. (Val-lau) | Venezuela, Táchira, Portachuelo, Xena 1366 – 1994 (VEN) | AF448582 |

| Valeriana officinalis L. subsp. tenuifolia Schübler & Martens (Val-off) | France, Gard, Massif de l'Aigoual, Mathez 1046 – 1996 (MPU) | AF448583 |

| Valeriana parviflora (Trevir.) Höck (Val-par) | Venezuela, Mérida, páramo Mucuchies, Xena 1359 – 1994 (VEN) | AF448584 |

| Valeriana phylicoides (Turcz.) Briq. (Val-phy) | Venezuela, páramo Mucubají, Xena 1363 – 1995 (VEN) | AF448585 |

| Valeriana pilosa Ruíz & Pavon (Val-pil) | Venezuela, Táchira, páramo Batallón, Xena 1346 – 1994 (VEN) | AF448586 |

| Valeriana rosaliana Meyer (Val-ros) | Venezuela, Táchira, páramo El Rosal, Xena 1356 – 1995 (VEN) | AF448587 |

| Valeriana sorbifolia H.B.K. (Val-sor) | Venezuela, Trujillo, Boconó, Xena 1354b – 1994 (VEN) | AF448588 |

| Valeriana tripteris L. (Val-tri) | France, Gard, massif de l'Aigoual, Mathez 1080 – 1997 (MPU) | AF448589 |

| Valerianella locusta (L.) Laterrade (VII-loc) | France, Hérault, Montpellier, Mathez 1035 – 1998 (MPU) | AF448590 |

| Valerianella coronata (L.) DC. (VII-cor) | France, Jardin des Plantes, Paris, sub V. pumila | AF448591 |

Leaves were collected in the field or in botanical gardens and desiccated in silica gel. Total cellular DNA was extracted from leaf tissue using the modified CTAB method [11,12]. Intergene amplification was made by PCR following standard procedure [7–9] and using universal primers designed by Manen [9]. Purified DNA was sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method ([13]) using a ‘Thermo Sequenase radiolabeled terminator cycle sequencing kit’ of Amersham and 33P-labeled nucleotides. Sequences were visualized using autoradiography.

A basic matrix of crude sequences was manually aligned using the MUST program [14], resulting in a total of 1119 positions (963 belonging to the intergenic zone and 156 to the first portion of the rbcL gene). The sequences of these 22 species are deposited in the EMBL/Gen Bank (accession numbers given in Table 1).

The portion of the rbcL gene included in our sequences does not display indels. The following treatments were performed for coding of indels present in the zone of the intergene atpβ-rbcL in this basic matrix:

- • ‘complete omission’: elimination of each site displaying one or more gaps representing an indel;

- • ‘missing data’: each gap is replaced in the matrix with a ‘?’, meaning that information at this site is missing for concerned species;

- • ‘fifth base’: each gap in the aligned matrix is replaced by a ‘D’, as if there were a fifth base;

- • ‘Barriel method’: the insertion of new columns replaces zones where at least one taxon displays a gap (an indel) as a way of identifying every potential evolutionary event and taking it into account only once, using the least amount of steps. This code introduces two new symbols, ‘i’ and ‘d’, which are necessary for representation of insertion/deletion events; in addition, “it is necessary to introduce question marks ‘?’… [which] are not missing data or lack in information, but are a methodological consequence of coding, neutral to a priori phylogenetic hypotheses” [10].

Phylogenetic analysis was performed on the two matrices (one non-coded for the three first methods, one coded by the Barriel method) with PAUP package version 4 for PCs [15]. Search for the most parsimonious trees used the Branch and Bound algorithm, with the MulTrees option. In order to evaluate the robustness of the internal nodes of the strict consensus trees obtained, Bootstrap analyses were performed (1000 replications of heuristic searches, using options AddSeq = Simple, Held = 100, Swap = NNI, MulTrees = No) and the Decay Index of each node calculated by the elegant ‘clad constraint method’ [16] with 100 replicates. ACCTRAN character-state optimization was used for all illustrated trees, and trees were drawn by the Treeview program [17,18].

3 Results and discussion

All indels are located in the intergene region of the aligned sequences. Within the ingroup of 21 species of Valerianeae, the length of the intergene varies from 788 (Valeriana dioica) to 531 bp (Fedia pallescens). The major indel appears as a long deletion of 311 bp (positions 319–629) which affects the sequences of all the analyzed species of the Fediinae subtribe (genera Fedia and Valerianella). Patrinia villosa, the species selected as outgroup, displays the longest sequence with a 809-bp long intergene. Aside from the case of the Fediinae subtribe, the length of the region studied is equivalent to that found by other authors in different taxonomic groups [7,8].

In the remaining species, there has been a considerable amount of evolution in the region of the large deletion of Fediinae. Some of these events, indels as well as nucleotide substitutions, appeared to be possible synapomorphies of supraspecific taxa. For this reason it is important to try to code indels correctly so as to avoid loss of information for parsimony analysis.

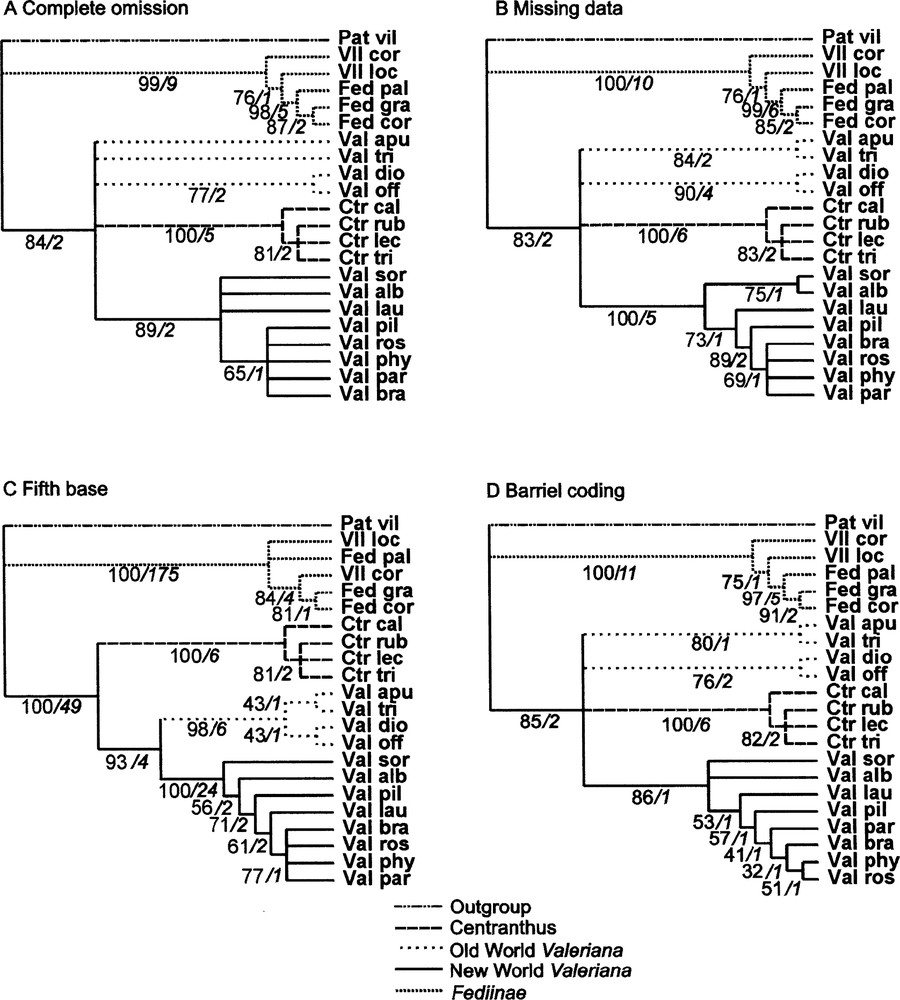

The first method we used (‘complete omission’) was to eliminate 461 sites affected by indels. As mentioned above, a large amount of information is lost this way: only 47 positions are informative among the remaining 658 ones. Results are given in the tree in Fig. 1A. Although we did not make use of the large deletion specific to Fediinae, this group of five species is well supported by the analysis. On the other hand, the four species of Centranthus come together supported by good bootstrap and decay values. The different species of Valeriana from the New World come out in the same less supported clade, but monophyly of the whole genus is not demonstrated.

Strict consensus cladograms issued from the four treatments performed (Technical information in text. Near branch information: Bootstrap percentage/Decay Index). A,B and C : crude matrix of 1119 characters. A: ‘complete omission' of 461 gapped sites (47 informative positions among 658 remaining; 14 trees of 126 steps; CI = 0.897, RI = 0.919, RC = 0.824). B: ‘Missing data' (62 informative positions; 24 trees of 191 steps; CI = 0.932, RI = 0.938, RC = 0.874). C: ‘fifth base' (371 informative positions; 24 trees of 716steps; CI = 0.892, RI = 0.951, RC = 0.849). D: new matrix of 739 characters after coding gaps using Barriel method (79 informative positions; 12 trees of 229 steps; CI = 0.860 RI = 0.878 RC = 0.755).

When the ‘missing data’ coding method is used, the regions displaying indels are not eliminated (1119 sites), so that substitutions of these regions bring information not used in the previous method: consequently, 62 positions are informative. However, not one of the evolutionary events corresponding to indels is taken into account. The resulting tree is very similar to the previous one (Fig. 1B), but with slightly better resolution for the genus Valeriana.

When the ‘fifth base’ method is used, each gap resulting from the alignment is filled with the new symbol ‘D’, as if there were a fifth base. Co-occurrence of several ‘Ds’ at the same position leads to the conclusion that there was an evolutionary event at this position. When the same indel affects several contiguous sites in two or more species, parsimony analysis results in several synapomorphies for a single evolutionary event, and even in certain cases for no synapomorphic event at all. So in many cases, actual synapomorphies are much overweighted. In our example, the ‘fifth base’ method gives 371 informative positions out of 1119, much more than the previous methods. Consequently, the resolution of the resulting consensus tree (Fig. 1C) is sharper than previous ones. The three major clades are consistent with the taxonomy of the group: Fediinae, Centranthus and Valeriana. Within the genus Valeriana, two clades are distinguished: one with the European species, and another with the American ones. The support for the clade Fediinae is impressive: this appears to be a consequence of the overweighting of the long deletion of this clade.

With the Barriel method, the coding is much more complex, because it strives to fully and accurately translate any type of change that occurs in a zone affected by an indel (each event is considered once and only once, and affected with the same weight). Because of the complexity of the coding method proposed by Barriel, we present here in detail one example of a segment of our aligned matrix located within the zone of the large deletion of the Fediinae (Fig. 2).

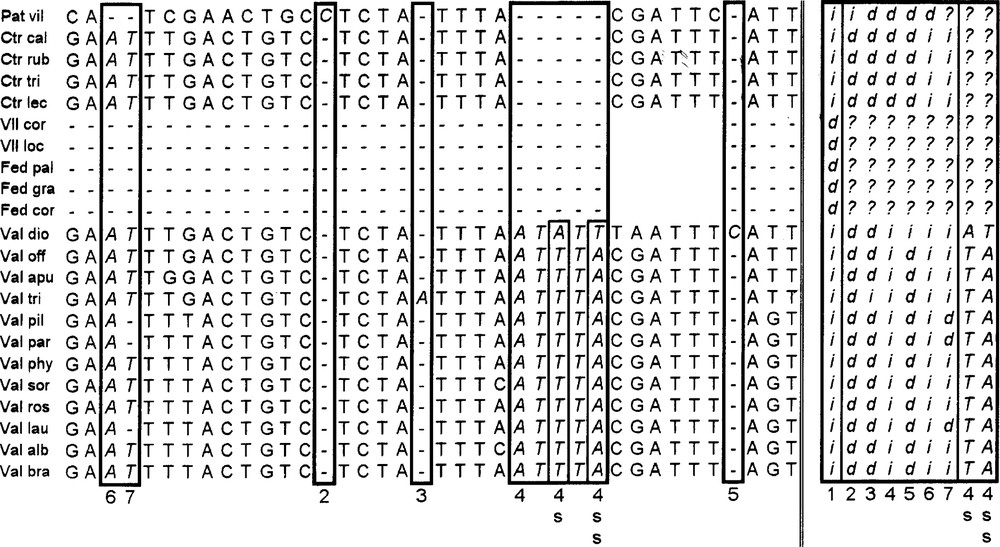

Selected region—within the area occupied by the large deletion presented by the species of the Fediinae subtribe—from the coding matrix of the atpβ-rbcL intergene region, according to the Barriel method. Explanation in the text.

Columns are inserted to replace the zones where at least one taxon displays a gap in the matrix. In a global view, each insertion–deletion event at a given position is coded in a new column by complementary symbols ‘i’, which replace the symbols of the bases at the position, and ‘d’, which replace the gaps resulting from alignment. In the following, the terms ‘insertion’ or ‘deletion’ are used in a relative sense and do not prejudge the actual evolutionary event.

So, column number 1 displays codes for the large deletion specific to Fediinae. In the frame at right (lower case letters), each numbered new column represents the coding of one or more framed columns of the left side (bold italic letters) where indels appear, identified in the figure with the same number.

Columns number 2, 3 and 5 respectively display codes for the insertion of one base at Patrinia villosa, Valeriana tripteris and V. dioica. The insertion of a five consecutive bp segment in all Valeriana species is considered as one evolutionary event coded in column 4. Within this segment, two substitutions affecting V. dioica (columns numbered 4s and 4ss, slender frame inside the large bold one) are superposed on to the insertion. The final coding of this region conserves the information corresponding to these two substitution events in columns 4s and 4ss at the right. In these columns, gaps are filled with question marks ‘?’, because corresponding events were yet coded in columns 1 and 4 (deletions in Fediinae, Centranthus and Patrinia).

Two independent events of columns 6 and 7 at the left are interpreted and coded in the most parsimonious way in corresponding columns 6 and 7 at the right: first (column 6 at the right), deletion of A and T at Patrinia; second (column 7 at the right), deletions of T at V. pilosa, V. parviflora and V. laurifolia. Each time a deletion is coded by a series of ‘d’ in a column at right (Patrinia in column 6, 3 species of Valeriana in column 7), other places of the column are filled by ‘i’ corresponding to nucleotides at the same sites of other species, or by question marks for the species at which a previous deletion event was coded (Fediinae in columns 6 and 7).

Finally, after coding of the gapped sites, all superfluous columns replaced by new coding ones in the matrix are eliminated. In the new matrix, 79 sites are informative (17 more than ‘missing data’, 32 more than ‘complete omission’). The strict consensus cladogram obtained by maximum parsimony analysis is presented in Fig. 1D, and may be compared with the three previous ones.

The phylogenies obtained using the four coding methods (Fig. 1A–D) have the same three main clades in common: one formed by all species of the monogeneric subtribe Centranthinae, the second constituted by American species of Valeriana; and the third corresponding to the subtribe Fediinae, represented by its genera Fedia and Valerianella. Centranthus and Fediinae clades are well supported by Bootstrap percentages of 99 to 100% and Decay index values all ≥ 5. The American Valerians clade displays similar scores, except for the Complete omission and Barriel’s methods (Bootstrap percentages respectively 89 and 86, Decay index 2 and 1). Fedia is also well supported within the Fediinae, except by the ‘fifth base’ method which does not recognize monophyly of this genus.

When the ‘complete omission’ (Fig. 1A) as well as the ‘missing data’ (Fig. 1B) or the Barriel’s (Fig. 1D) methods are used, the Valerianinae subtribe is never found to be monophyletic, but the clade of American species is recovered. The same clades are more or less supported in the three consensus trees. The ‘missing data’, ‘fifth base’ and Barrielˈs results give better resolution in the American group of Valeriana, corresponding to the fact they exploit a larger number of informative sites than ‘complete omission’.

The ‘fifth base’ method is unable to recover the genus Fedia (Fig. 1C). However, only this method identifies a monophyletic Valeriana genus (or Valerianinae subtribe), made up of two well resolved clades grouping American species and European ones respectively. Before arriving at the taxonomic implications of this, these phylogenic results must be confirmed in future studies. Among other methodological improvements, taxon sampling must be enlarged both for ingroup and outgroup species (selected in families near Valerianaceae).

Concerning the best coding strategy, our study shows that taking indels into account or not does not lead to drastic differences. However, about one third of informative sites of the atpβ-rbcL intergene of Valerianaceae are concerned with insertion or deletion events. Complete omission of such sites does not obscure major phylogenic signals responsible for the three major clades of cladograms in Fig. 1. It is clear that the three other methods lead to better resolution of Valeriana phylogeny, the finest result proceeding from the ‘fifth base’ method. Nevertheless, this result must be examined cautiously, remembering that by this method each indel is weighted proportionally to its length. On the other hand, systematic overweighting related to application of the ‘fifth base’ method leads to results that obscure real relationships (for example between the three Fedia species) and is thus unacceptable.

So it seems careful in future studies to use both ‘missing data’ (alone or associated with other methods as in most recent studies of molecular phylogeny [9,19–25]) and indel presence/absence coding methods such as Barriel’s (also used in comparison with ‘missing data’ [6,23,25]).

Given that the theoretical basis of the Barriel’s method has a priori more evolutionary relevance, we think that it is more likely to give results which correspond better to the actual phylogeny, despite the ‘sharper’ resolution of the ‘fifth base’ method. The phylogenetic signal of our data is sufficient to recover the major clades, whatever the method used. So we can wonder whether the demanding and laborious application of Barriel’s method is really justified for our data, unless it is computerized. In other respects, the two most credible methods, ‘missing data’ and Barriel’s, result in weakly resolved or supported phylogenies at two levels: that of Valeriana species, that of relations between the Valeriana and Centranthus clades. We think that this is due to the limits of resolution proper to our molecular marker, as well as the lack of a sufficient number of Valeriana species in our sample.

4 Conclusion

When comparing sequences containing important insertion–deletion zones, in one or several of the studied taxa, it is important to use a coding method that represents as truthfully as possible the evolutionary events shown in the alignment, without adding false nor losing actual information.

In the case described in this study, four different methods of treating indels give very similar phylogenetic reconstructions. This seems to indicate that the substitutions in the sequences of the intergene atpβ-rbcL provide enough information for grouping some taxa in the more robust clades (subtribes Fediinae and Centranthinae, American Valerians), and demonstrating their monophyly even if the indels were not taken into consideration (‘complete omission’ and ‘missing data’ methods) or were overestimated (‘fifth base’). Nevertheless, ‘missing data’ and Barriel’s methods give the most reliable and finely resolved results within some of these more robust clades.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Service Commun de Biosystématique of the Institut des Sciences de lˈEvolution of the Montpellier II University, particularly F. Catzeflis, director of the laboratory, where the data used for this study were generated. We are grateful to Fred R. Barrie (Missouri Botanical Garden), J. El Oualidi (Institut Scientifique, Rabat, Morocco), A. Fridlender, J. Molina (Conservatoire Botanique National Méditerranéen de Porquerolles, Montpellier), and Teresa Navarro (University of Málaga, Spain) for kindly providing plant material. Special thanks to Véronique Barriel (Muséum National dˈHistoire Naturelle, Paris) for helping us apply her method to our data, and to Dawn Frame for correcting the English redaction. The study was partly financed by the international cooperation project CNRS (5487) – CONICIT (PI136), as well as by fund obtained within the framework of the ACC-SV7 Réseau National de Biosystématique at the Montpellier II University.

Version abrégée

L’intergène chloroplastique atpβ-rbcL (environ 900 paires de bases ou pb) a la réputation d’être un marqueur moléculaire bien adapté à la reconstitution de phylogénies de genres ou de taxons de niveaux supérieurs. C’est pour cette raison que nous l’avons choisi en vue de préciser les relations entre les différents genres de la tribu des Valerianeae. Pour aligner les séquences obtenues, nous avons été amenés à insérer de nombreuses discontinuités (« gaps »), c’est-à-dire à faire appel avec une fréquence particulièrement élevée à des événements évolutifs d’insertion–délétion (« indels ») : plusieurs espèces auraient perdu ou acquis des segments longs d’une à plus de 300 pb. Ces gaps augmentent sensiblement les difficultés d’alignement, et posent des problèmes lors de l’application des méthodes de parcimonie, d’autant plus qu’ils se superposent ou se combinent souvent à des substitutions de nucléotides affectant les séquences des autres taxons. Cette étude préliminaire se propose d’évaluer l’incidence des différentes façons de traiter les indels sur les résultats des analyses de parcimonie.

Notre matériel d’étude comporte 21 espèces de Valerianaceae appartenant aux genres Centranthus, Fedia, Valeriana et Valerianella, représentatifs des quatre sous-tribus des Valerianeae. Le genre Valeriana est représenté par des espèces américaines et européennes. La recherche d’un bon groupe extérieur nous a amenés à tester plusieurs espèces de tribus et de familles voisines au cours de différents essais préalables. Tous les résultats concordaient pour assigner à Patrinia villosa la position de goupe frère des Valerianeae, ce qui nous a conduits à la retenir seule pour cette étude.

Une fois alignées, les séquences des 22 espèces occupent une longueur totale de 1119 positions, dont 963 appartiennent à l’intergène proprement dit, et 156 au début du gène rbcL adjacent. Les indels n’affectent que l’intergène, dont la longueur varie de 788 à 531 pb chez les 21 espèces de Valerianeae. Le plus important de ces indels se manifeste comme une grande délétion de 311 pb, commune à toutes les espèces étudiées de la sous-tribu des Fediinae (Fedia et Valerianella). Quant à l’espèce choisie comme groupe extérieur, Patrinia villosa, elle possède l’intergène le plus long (809 pb).

Il importe de souligner que, entre les limites de la grande délétion propre aux Fediinae, les autres espèces de Valerianeae présentent toute une série d’indels et de substitutions de nucléotides.

Une première méthode de traitement des gaps, dite « d’omission intégrale » consiste à éliminer tous les sites comportant au moins un gap : elle prive donc l’analyse de toute l’information phylogénétique portée par les indels eux-mêmes et par les substitutions présentes aux sites correspondants. Sans doute adaptée aux ensembles de séquences où les indels constituent des événements rares, cette méthode semblait a priori mal convenir à nos données. Une autre méthode classique, dite « des données manquantes », consiste à remplacer par un point d’interrogation chaque position affectée par un gap, donc à négliger toute l’information apportée par les événements d’insertion–délétion. Souvent utilisée également, la méthode « de la cinquième base » consiste à traiter chaque position affectée par un gap comme un nucléotide appartenant à une même catégorie virtuelle et susceptible de se substituer en chaque site aux quatre nucléotides réels A, C, G et T. Toute l’information disponible est certes ainsi exploitée, mais avec une pondération qui a fait l’objet de critiques justifiées. Proposée plus récemment, la méthode de V. Barriel s’efforce de distinguer tous les événements évolutifs et de les prendre en compte une fois et une seule dans l’analyse au moyen d’un codage méthodique. A cet effet, les blocs de colonnes comportant des gaps sont remplacés dans la matrice par de nouvelles colonnes où peuvent figurer 3 symboles : « i » (hypothèse d’insertion), « d » (hypothèse réciproque de délétion), et « ? », indispensable pour ne pas compter plusieurs fois le même événement d’indel, ce qui aurait pour conséquence de lui attribuer un poids injustifié.

Pour comparer ces quatre méthodes de traitement des données dans une analyse de parcimonie, deux matrices ont été nécessaires : l’une de données brutes, l’autre de données codées par la méthode Barriel. Les options disponibles du logiciel PAUP permettent en effet d’appliquer directement les trois premières méthodes à la même matrice de données non codées.

L’application de la méthode « d’omission intégrale » restreint le nombre de sites retenus à 658, dont seulement 47 informatifs. Celles des « données manquantes » et de la « cinquième base » exploitent la totalité des 1119 sites de la matrice et totalisent respectivement 62 et 371 sites informatifs. Ce dernier nombre est bien plus élevé que les deux autres, puisque chaque position de chaque séquence apporte alors une information. Avec la méthode Barriel enfin, le nombre de sites informatifs obtenus après codage est de 79.

Les quatre phylogénies obtenues ont beaucoup de points communs. Elles mettent en évidence les trois mêmes clades : le genre Centranthus, constituant à lui seul la sous-tribu des Centranthinae, et la sous-tribu des Fediinae, l’une et l’autre soutenues par des valeurs de bootstrap de 99–100% et des indices de decay tous ≥ 5 ; le clade des espèces américaines de Valeriana, un peu moins robuste cependant. Le genre Fedia est également bien soutenu, sauf par la méthode de la « cinquième base » qui ne met pas en évidence sa monophylie. Cette dernière méthode est en revanche la seule à identifier un genre monophylétique Valeriana regroupant un clade d’espèces européennes et un d’espèces américaines.

Ainsi, le signal phylogénique contenu dans notre matrice de données est-il suffisamment puissant pour mettre en évidence trois clades principaux quelle que soit la méthode utilisée, même après élimination de tous les sites affectés de gaps (« omission intégrale »). Cependant, la résolution des cladogrammes obtenus est d’autant plus fine que le nombre de sites informatifs exploités est plus élevé. La méthode de la « cinquième base » est-elle pour autant la meilleure ? Rien n’est moins certain, dans la mesure où chaque indel y est affecté d’un poids proportionnel à sa longueur, ce qui est à coup sûr excessif. En effet, lorsque les nécessités de l’alignement nous ont amenés à introduire un gap de même longueur et de même position dans les séquences de plusieurs taxons, la méthode générale de parcimonie que nous avons choisie impose de faire l’hypothèse d’un événement évolutif unique et synapomorphique. Or la méthode de la « cinquième base » fait au contraire l’hypothèse d’un nombre d’événements évolutifs égal au nombre de positions affectées, ce qui revient à autant de synapomorphies : cette interprétation n’est pas compatible avec notre choix initial de la parcimonie. C’est la raison pour laquelle cette méthode conduit à des indices de decay parfois très élevés : ainsi, la longue délétion caractéristique des Fediinae explique que la méthode de la « cinquième base » confère à ce clade un indice de decay exceptionnel de 175. En revanche, au sein des Fediinae, elle est incapable de mettre en évidence le petit genre Fedia (trois espèces), si bien caractérisé et si peu suspect de paraphylie.

Dans ces conditions, la méthode Barriel nous semble la plus justifiée des quatre, dans la mesure où elle exploite la totalité de l’information disponible (ce qui n’est pas le cas de « l’omission intégrale » ou des « données manquantes »), avec parcimonie et sans pondération excessive des indels (à la différence de la « cinquième base »). Cependant, en l’absence de programme informatisé disponible (celui-ci est en cours de réalisation), sa mise en œuvre est bien laborieuse pour un résultat sans doute plus fiable, mais quasi identique à celui obtenu par la méthode des données manquantes.

Annex 1.

Classification of the Valerianaceae according to Weberling (1970) [5].

I. Tribe: Patrinieae Höck

1. Patrinia Juss.

2. Nardostachys DC.

II. Tribe: Triplostegieae Höck

3. Triplostegia Wallich ex DC.

III. Tribe: Valerianeae Höck

Subtribe: Fediinae Graebner (emend. Weberling)

4. Plectritis DC.

5. Valerianella Miller

6. Fedia Gaertner

Subtribe: Valerianinae Graebner (emend. Weberling)

7. Valeriana L.

8. Astrephia Dufr.*

9. Stangea Graebner*

10. Aretiastrum (DC.) Spach*

11. Phyllactis Pers.*

12. Belonanthus Graebner*

13. Phuodendron Graebner*

Subtribe: Centranthinae Graebner.

14. Centranthus DC.

*The identity of these exclusively South American genera has been questioned, some authors prefer to consider them as sections of Valeriana (see [26]).