Version française abrégée

La prolifération des cyanobactéries, liée à l'eutrophisation des lacs et rivières, génère d'importantes nuisances, aussi bien au niveau écologique, touristique que de la santé humaine. De nombreuses études sont actuellement menées afin de comprendre les mécanismes impliqués dans la formation de ces efflorescences à cyanobactéries.

Notre étude a été réalisée sur la retenue de Grangent, localisée sur la Loire, à proximité de Saint-Étienne, dans le Massif central français. L'espèce de cyanobactérie dominante est Microcystis aeruginosa. Cette cyanobactérie apparaît dès le printemps dans la colonne d'eau, se développe abondamment en été, puis périclite et gagne le sédiment en automne. Pendant l'hiver, les colonies restent sur le sédiment à l'état végétatif. Une partie d'entre elles est ensuite capable de regagner la colonne d'eau au printemps et constitue alors un inoculum pour les futures efflorescences estivales.

Nous avons tout d'abord réalisé une étude préliminaire afin de déterminer la distribution des colonies benthiques à l'échelle de la retenue. Le sédiment a été prélevé sur 14 stations différentes, en avril 2000, à l'aide d'une benne mécanique. Au laboratoire, le sédiment a été filtré sur un filtre de maille 50 μm et les cyanobactéries ont été comptées sous microscope (×100). Le sédiment est ensuite séché à 60 °C puis pesé.

Les résultats de cette étude préliminaire ont révélé une distribution très hétérogène des colonies benthiques de M. aeruginosa. Les plus fortes concentrations ont été obtenues dans les zones à sédiment fin, riche en matière organique et profonde (). Inversement, les plus faibles valeurs ont été décelées sur les sédiments sableux de faible profondeur. Cette distribution peut être en partie due à une sédimentation limitée en zone sublittorale ou à une remise en suspension du sédiment des zones peu profondes qui se redépose ensuite en zones profondes. Les importantes concentrations de cyanobactéries trouvées dans les sédiments profonds résultent donc probablement d'une accumulation répétée depuis plusieurs années.

Dans un deuxième temps, quatre sites ont été sélectionnés pour un suivi estival de mai à octobre 2000 : trois stations de différentes profondeurs situées en aval de la retenue – Cam 5 (5 m, faible profondeur), Gra 13 (13 m, profondeur intermédiaire), Cam 45 (45 m, forte profondeur) – et une station en amont – Per 10 (10 m, faible profondeur). Les cyanobactéries benthiques ont été dénombrées comme indiqué précédemment lors de l'étude préliminaire. De la même manière, les cyanobactéries planctoniques ont été échantillonnées à chaque station à 0,5, 2,5, 15 et fond grâce à une pompe filtrante. Les paramètres abiotiques classiquement étudiés ont été mesurés (température, teneur en oxygène dissous, concentration en orthophosphate, en ammonium, en nitrate et silice).

Ce suivi estival a mis en évidence d'importantes variations au niveau des concentrations de cyanobactéries benthiques et a permis de distinguer deux types de dynamique.

D'une part, dans la partie aval de la retenue, aux stations Gra 13 et Cam 45, les concentrations en M. aeruginosa benthiques sont élevées et fluctuent fortement au cours du temps. Ceci peut être en partie expliqué par la dynamique des colonies planctoniques de M. aeruginosa, qui présente une succession de pics éphémères à la suite desquels les cyanobactéries sédimentent. L'augmentation en colonies benthiques est constatée sur le sédiment avec deux à trois semaines de décalage, correspondant au temps de sédimentation des colonies de M. aeruginosa en zone profonde.

D'autre part, aux stations localisées à proximité des berges ou en système fluvial (Cam 5 et Per 10), le nombre de cyanobactéries benthiques reste faible et relativement constant pendant toute la période estivale. Ceci est vraisemblablement dû aux mauvaises conditions de sédimentation (pentes de berge abruptes) dans ces zones.

Cette étude a donc tout d'abord montré l'hétérogénéité de la distribution des colonies benthiques de M. aeruginosa à l'échelle d'une retenue. Cette répartition est notamment contrôlée par de nombreux facteurs externes tels que la nature du substrat, la hauteur d'eau, le régime hydraulique ou la morphométrie de la station. De plus, malgré un niveau d'eau stable en période estivale, le nombre de colonies benthiques fluctue de façon importante, en relation avec la dynamique chaotique des colonies planctoniques. Les interactions entre les cyanobactéries benthiques et planctoniques doivent maintenant être approfondies au cours d'une étude annuelle de la dynamique de M. aeruginosa et du processus de recrutement benthique.

1 Introduction

Anthropic eutrophication of lakes and fresh water rivers has been known for several years [1–5]. The problem is mainly caused by excessive nutrient concentrations. Accelerated enrichment of water often leads to the proliferation of phytoplankton, with cyanobacteria predominating. These procaryotes can form thick layers on the water surface in the bloom period, which are nowadays causing problems for the users and managers of aquatic environments. Indeed, some cyanobacteria are able to synthesize toxins [6–12], representing a risk to human and animal health. Moreover, cyanobacterium bloom can cause severe imbalances in trophic systems, with visually and olfactively harmful effects.

The Grangent Reservoir, on the River Loire, is important for energy production and the irrigation of the Forez plain. With its boating resort of Saint-Victor-sur-Loire, it is an attractive touristic site. Starting at the end of 1970, high external phosphorus loads caused the hypertrophication of the reservoir and summer blooms of Microcystis aeruginosa were observed for several years [4].

In temperate lakes, M. aeruginosa appears in the water column at the end of spring. This cyanobacterium forms blooms during the summer period, then sinks and reaches the sediment in autumn [13–15]. In winter, the colonies of M. aeruginosa remain on the sediment as vegetative cells [13,16,17]. The colonies that survive the winter [13,16,18] constitute an inoculum for the following year and, in spring, part of them regain the water column [19]. These benthic M. aeruginosa, thus, play an important role in the cycle of this cyanobacteria and, particularly, in the formation of summer bloom.

We first studied the distribution of the benthic M. aeruginosa in the whole reservoir in order to locate possible accumulation zones. Then, we attempted to describe the factors supporting the dynamics of the benthic cyanobacteria by carrying out a spatial and temporal monitoring of the benthic and planktonic colonies.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study site

Grangent Reservoir, located near Saint-Étienne, in the upper part of the River Loire, was created in 1957. Its area is 365 ha, with a length of 21 km, a maximum width of 400 m, a maximum depth of 50 m and a volume of . This reservoir may be subdivided into a downstream more lacustrine part and an upstream more fluvial part.

The surface of the hydrological basin is 3850 km2. The annual medium flow entering the reservoir is of 40.6 m3/s with a maximum of 370 m3/s (in periods of strong rising: autumn) and a minimum of 5 m3/s (only in summer). Water renewal time in the reservoir varied between 10 and 16 days. The principal function of this reservoir is the production of electricity. An important tourist activity is also developed. Thus, the maximum variation of the water level is 10 m (i.e. between 410 and 420 NGF) but must be maintained between 419 and 420 NGF from 1 June to 15 September because of summer activity in this reservoir.

2.2 Preliminary study

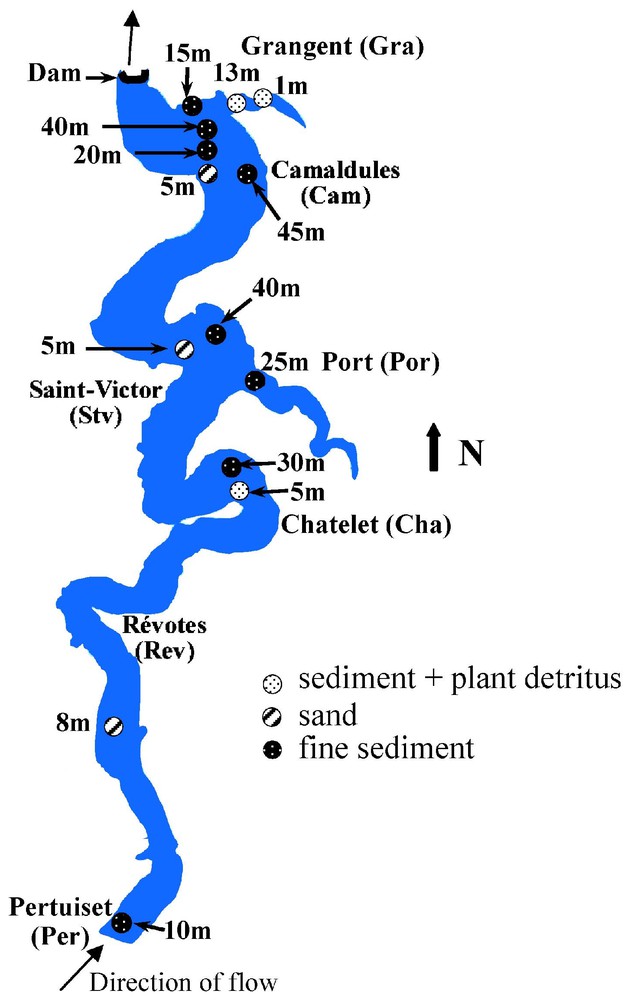

To evaluate the distribution of the benthic colonies on the bottom of the reservoir, 14 different profile stations (depth, substratum, light) were sampled in April 2000 (Fig. 1). At each station, the sediment was collected in triplicate with a clamshell bucket that sampled the upper five centimetres of the sediment. In the laboratory, an amount of 150 ml of each sample was filtered on a filter with 50-μm meshes and the colonies of M. aeruginosa (containing an average of cells) were counted on the filter under the microscope (×100). Then, the sediment was dried at 60 °C during several days then weighed.

Substratum and depth (m) of stations sampled for the preliminary study.

These data obtained for 14 sites in triplicate were analysed by ANOVA in order to detect significant differences. Then, post-hoc pairwise tests (Fisher and Scheffé tests) were used to compare sites two by two and to determine which sites statically differed.

2.3 The summer study

The preliminary study allowed us to select four sites which were then studied from May to October 2000: three stations at different depths located downstream: Cam 5 (5 m, shallow depth), Gra 13 (13 m, intermediate depth) and Cam 45 (45 m, great depth); and one station upstream: Per 10 (10 m, shallow depth). At each station, the benthic colonies of M. aeruginosa were counted as indicated previously. In parallel, planktonic cyanobacteria were sampled at 0.5 m, 2.5 m, 15 m depth and bottom (e.g. 1 m above the sediment), using an electric pump equipped with a 50-μm mesh net and filtering 100 l of water. This volume was chosen in order to concentrate M. aeruginosa colonies especially when biomass was low. Indeed, methods of sampling with a Van Dorn bottle were unsuitable for the colonial form of M. aeruginosa and induced an underestimation of cyanobacterian biomass [20]. Then each sample was filtered on a net with 50-μm meshes in the laboratory and colonies were counted under the microscope.

For each station, we obtained one temporal series for benthic cyanobacteria dynamics and between two and four series, according to the depth of the station, for planktonic cyanobacteria dynamics. These data were statistically analysed by ANOVA. Post-hoc pairwise test (Fisher and Scheffé tests) were used to compare successive values two by two to determine temporal changes within stations.

Temperature and oxygen profiles were established for the three stations Per 10, Cam 45 and Gra 13. The main physicochemical data were obtained from a sample of water collected with a Van Dorn bottle upstream (Per 10) and downstream (Cam 45) at 0.5-m, 2.5-m, and 10-m depth. Water transparency, measured with Secchi disc [21], orthophosphates (according to the spectrophotometric method of Motomizu et al. [22]), ammonium (according to spectrophotometric method AFNOR T90.015 [23]), nitrates (according to Rodier's [24] spectrophotometric method) and silica concentrations (according to colorimetric method AFNOR NF T90.007 [23]) were measured.

3 Results

3.1 Benthic cyanobacteria

The preliminary study showed significantly different densities of benthic M. aeruginosa among the stations (ANOVA, ). Those which significantly differed – Fisher for post-hoc pairwise comparisons () – were, on the one hand, stations with higher concentrations: Cam 20 (40.46 colonies/g), Cam 40 (35.80 colonies/g), Cam 45 (39.60 colonies/g), Gra 13 (49.30 colonies/g) and Por 25 (38.40 colonies/g), and, on the other hand, Cam 5 (1.27 colonies/g), Gra 1 (1.05 colonies/g), Stv 5 (0.06 colonies/g), and Cha 4 (0.60 colonies/g) with lower benthic cyanobacteria concentrations (Fig. 2). Thus, it appeared that M. aeruginosa were more numerous in fine sediments with much organic matter and in the deeper sites (). In contrast, the smallest concentrations of cyanobacteria were found in sandy substrata at low depths.

Enumeration (number of colonies/g dry sediment) and spatial distribution of benthic colonies in the preliminary study.

Moreover, dynamics of benthic colonies showed temporal changes, e.g. comparison of dates two by two for each station gave significant differences ().

The summer study at the four stations allowed us to identify two different dynamics. Similar fluctuations were observed at Gra 13 (intermediated depth) and Cam 45 (great depth) where the benthic concentrations of cyanobacteria were greatest on 22 June, with 125 colonies/g of dried sediment for instance at Cam 45 (Fig. 3). Lower peaks were recorded on 26 July and on 9 August at these stations. Both stations were located downstream, in the lacustrine part of the reservoir, as opposed to the upstream fluvial part.

Spatio-temporal succession of benthic colonies.

The number of benthic colonies observed at Per 10 and Cam 5 (shallow depth) was relatively small (<5 colonies/g of dried sediment). This number remained stable throughout the summer period.

3.2 Planktonic cyanobacteria

The planktonic cyanobacteria were widely dominated by M. aeruginosa even if other species like Anabaena flos-aquae, Anabaena spiroides and Aphanizomenon flos-aquae were also present in small numbers (lower than cells/l). Contrary to the benthic M. aeruginosa dynamics, planktonic dynamics showed no significant difference between the four stations (). M. aeruginosa appeared in May in the downstream part of the reservoir at very low concentrations (<30 colonies/l with an average of cells/colony at Cam 45 and Gra 13). Until August, peaks of abundance were observed in the epilimnion of the three downstream stations, whereas M. aeruginosa was not really present upstream (Fig. 4). Starting in mid-August, strong sporadic epilimnic growths occurred at the shallowest stations: on 17 August and 20 September at Cam 5; on 27 September in Per 10 and Gra 13, where the development was greatest with 300 colonies/l (with an average of cells/colony). Deeper than 15 m, the cyanobacteria appeared in very small quantities and peaks of abundance were sometimes delayed compared to those of the surface.

Spatio-temporal changes in planktonic cyanobacteria abundance at 0.5-m depth.

3.3 Physicochemical factors

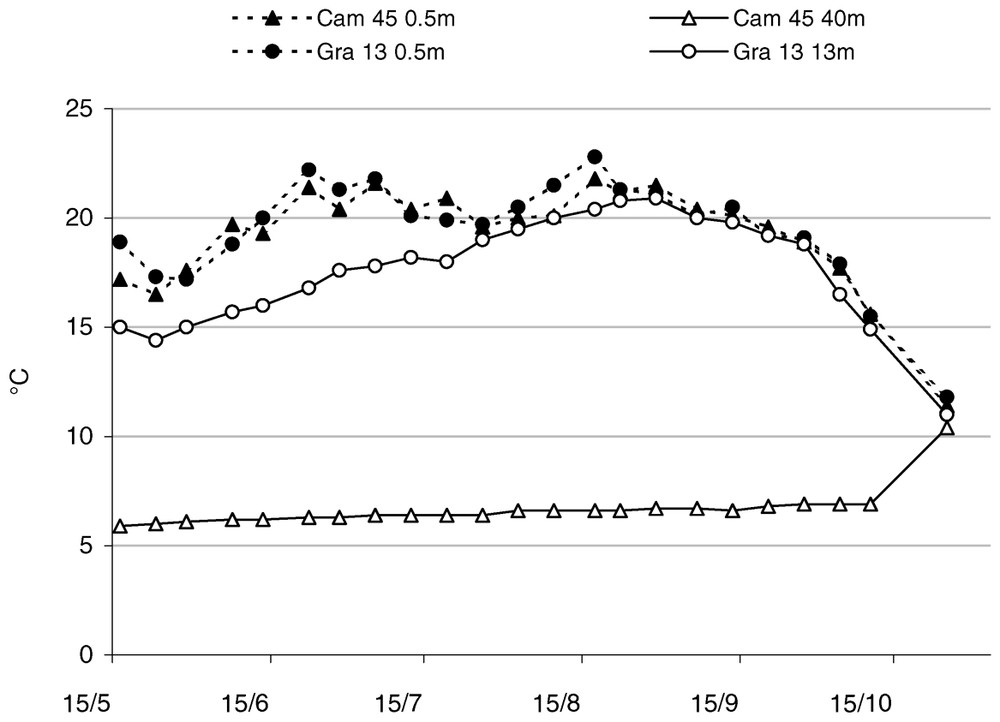

Epilimnic water temperature showed seasonal changes (): the values increased until August reaching a maximum of 22.8 °C, then decreased gradually from September. The same changes occurred at 13-m depth, but with lower values. At 40 m, an average temperature of 6.5 °C was maintained throughout the summer (Fig. 5). The thermal stratification of the lake began at the end of March with the presence of a weak thermocline at 30 m.

Comparison of the temperatures at the water surface (0.5 m) and at the bottom (40 m or 13 m) at downstream stations.

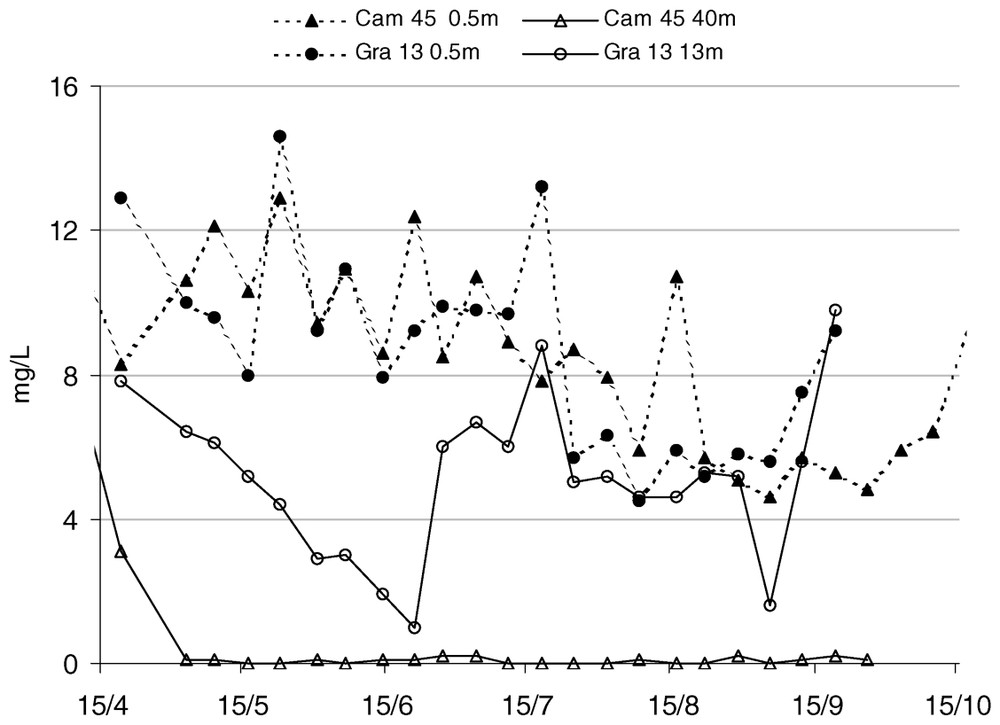

During the summer (until August), oxygen concentrations showed significant changes according to various depths (). The values varied between 8 and 15 mg/l at the surface, in a similar way at Gra 13 and Cam 45 (Fig. 6). This did not occur at 40 m, where oxygen concentration was almost zero since the month of May and remained so throughout the season.

Comparison of oxygen content at the water surface (0.5 m) and at the bottom (40 m or 13 m) at downstream stations.

Nutrient concentrations were no limiting factor for planktonic organisms (Fig. 7) and only silica concentrations showed significant temporal changes (). The amount of phosphates varied between 0.15 mg/l (spring and early summer) and 0.25 mg/l (late summer). On the other hand, there was an excess of nitrates with an average content of about 2 mg/l. Silica was also present at high concentrations (higher than 7 mg/l) throughout summer. Ammonia contents were low () during the study.

Nutrient content at station Cam 45 at 0.5-m depth.

4 Discussion and conclusion

4.1 Distribution of benthic M. aeruginosa

Benthic cyanobacteria were found in large numbers in the sediment of the Grangent reservoir with M. aeruginosa as the dominant species (99% of cyanobacteria taxa, [25]). According to Brunberg [26], Microcystis may constitute up to 90% of the total benthic biomass. However, the distribution of the colonies on the bottom of the reservoir was not homogeneous. The greatest concentrations of benthic colonies were found at the deep sites, with maximum values at 45-m depth. These results are in agreement with other studies, particularly those of Fallon and Brock, Reynolds et al. and Takamura et al. [13,14,16]. According to Reynolds et al. [13], this distribution could either be due to a limited sedimentation in the intermediate sublittoral zones or to a resuspension from shallows stations and redeposition in deeper zones. Sirenko [27] also stated that fewer colonies survive in oxygenated shallow water. This is probably the reason why a higher concentration of cyanobacteria was observed in deep zones (). In the same way, Brunberg [26] noticed that the anoxic conditions registered in deep water seem to prolong the survival of Microcystis in the sediment. Massive concentration of cyanobacteria in deep sediments could also result from a repeated annual accumulation [28].

However, some stations located at an intermediate depth (13 m) contained high concentrations of M. aeruginosa. These sites were characterized by fine sediment with many plant fragments. They can be interpreted as ‘quiet zones’, favourable to the sedimentation and the accumulation of cyanobacteria.

4.2 Summer dynamics of M. aeruginosa

Despite of a stable water level (420 NGF) and a minimum flow during summer, the number of benthic colonies fluctuated and this distribution varied according to the stations. Two types of dynamics can be clearly distinguished.

On the one hand, in the lacustrine system (Cam 45 (great depth) and Gran 13 (intermediate depth)) concentrations of cyanobacteria were high and fluctuating. This can partly be explained by the dynamics of planktonic cyanobacteria. Indeed, when planktonic concentrations decreased, we observed an increase in benthic concentrations. This corresponds to the sedimentation of a part of the planktonic forms. This sedimentation was due to the decrease of gas vesicles [29] and/or an increase in carbohydrate ballast [30]. However, the increase in the number of colonies in the sediment was observed two to three weeks after the decrease observed in the epilimnion. This might correspond to the time of sedimentation of M. aeruginosa in the deep zones of the Grangent Reservoir. No direct correlation could be established between the number of hypolimnetic colonies and benthic colonies, probably because part of the summer population may disappear by decomposition or by being consumed by bacteria, rhizopoda or ciliates [14].

On the other hand, at the stations located near the banks or in the fluvial systems – Cam 5 and Per 10 (shallow depth) –, concentrations of benthic colonies remained rather low and stable. This was probably due to the unfavourable conditions for benthic accumulation (abrupt slope) and the more instable conditions of these sites during a year.

The distribution of benthic Microcystis aeruginosa in the Grangent Reservoir was not regular and appears to be controlled by many external factors: nature of substratum (fine sediment, sand, plant detritus…), which could favour an heterotrophic activity of benthic M. aeruginosa [13], lake depth, hydraulic regime (fluvial or lacustrine), station morphometry… These results show that sampling strategy plays an important role for biologic study of M. aeruginosa cycle. In spite of a stable water level and a minimum flow during summer, the number of benthic colonies showed great variation in the lacustrine downstream part. These variations could be partly explained by the dynamics of the planktonic cyanobacteria and the characteristics of M. aeruginosa (heterogeneous repartition within a bloom [25] and buoyancy regulation [13]).

The interactions between the benthic and planktonic cyanobacteria can be ascertained by improving sampling methods, by using a core drill, and studying only a fine layer on the surface of the sediment. This will allow us to follow the annual dynamics of the benthic cyanobacteria and the recruitment process.