1 Introduction

Identification of carbonate polymorphs is fundamental in biogenic processes and in palaeoenvironmental studies by means of isotopes [1,2]. Discrimination between biogenic and diagenetic carbonates is also an important clue in taphonomic processes and interpretations.

Otoliths are small calcium carbonate biogenic crystals: they are not part of the skeleton, but are immersed in endolymph-filled chambers of the inner ear of fishes. Teleostean fishes typically have three pairs of otoliths, namely lapilli, asterisci and sagittae [3]. The sagitta is generally the biggest otolith; it displays large shape, size and pattern variations which often are species-specific [4].

Otoliths play an important role in sensory and balance functions: in association with the hair cells of the sensory epithelium (macula), they sense gravity, linear acceleration, and sounds [5]. Within water environment, sound reception is fundamental for perception of congeners, preys and predators. The perception of the movements of acceleration and the maintenance of postural equilibrium are also very important for swimming and survival. Hence, a dysfunction of the otolithic organ should have important physiological outcomes.

Relevance of otolithic material for systematic identification of modern, archaeological, and fossilized fish species is well demonstrated [6]. In addition to this classical systematic application, otoliths are biogenic structures, fine study of which can provide useful data on physiology and living conditions of fishes [7], by means of growth increments, trace elements or isotope analysis [8]. Thus, such data can be used to reconstruct palaeoecological environment of fishes. Nevertheless, such applications require very fine studies on the structure and composition of the otolith, and aragonite/calcite discrimination is of primary importance [1].

As early noticed by Cuvier [9], the main constituent of otoliths is anhydrous calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Three crystalline polymorphs of calcium carbonate have been identified in teleost otolith: calcite, aragonite, vaterite, in addition to calcium carbonate monohydrate [10]. Aragonite is the most common polymorph [10–13]. Otoliths also contain organic material, a protein named otolin [12], organized as a matrix, and which probably orientates CaCO3 crystal growth, like in the avian eggshell mineralization [14]. This process of biomineralisation that involves accretion of aragonite is constant throughout the life of the fish, although irregular (daily or seasonal variations of growth, reproduction period, etc.). In normal physiological conditions, each material deposited is preserved through time: this makes the otoliths good time- and life-history-keeping hard structures [15].

Anomalous otoliths have been known for decades from several marine fish species, but seem to be uncommon [10]. They were reported from Engraulidae, Clupeidae, Salmonidae, Ophidiidae, Macrouridae, Gadidae, Moronidae, and Pleuronectidae families [13,16–25]. Their relative proportions in a wild population vary between 1 and 5.5% [13,16,21–23,25].

Several anomalous otoliths were discovered during a recent investigation on otoliths of Peruvian marine fishes and while analysing fish remains from a coastal archaeological site [26]. Two species of Sciaenidae were concerned with, in both modern and archaeological specimens: Cilus gilberti (Abbott, 1899) and Sciaena deliciosa (Tschudi, 1846). This paper provides new evidence for different polymorphs of calcium carbonate among Teleostei. Their identification and spatial distribution among anomalous otoliths were explored using non-destructive microanalysis methods. Previous X-ray diffraction identification of otoliths required complete crushing [10,13]. In order to preserve the otoliths integrity, X-ray analyses were performed on small (

2 Material and morphometry

Several modern and archaeological otolith lots of Cilus gilberti and Sciaena deliciosa were selected for the present study. Only sagittae that are the biggest otoliths in these sciaenids are considered here. Modern material was collected along the Pacific coasts of Peru, between Callao (12°S) and Ilo (18°S), and Chile, at Antofagasta (23°S). The archaeological otoliths come from the archaeological site of ‘Quebrada de los Burros’, located in southern Peru (18°00′S, 70°50′W), close to the Chilean border. They were collected in level 3 of the excavation, which has been dated between 7000 and 8000 BP [28,29].

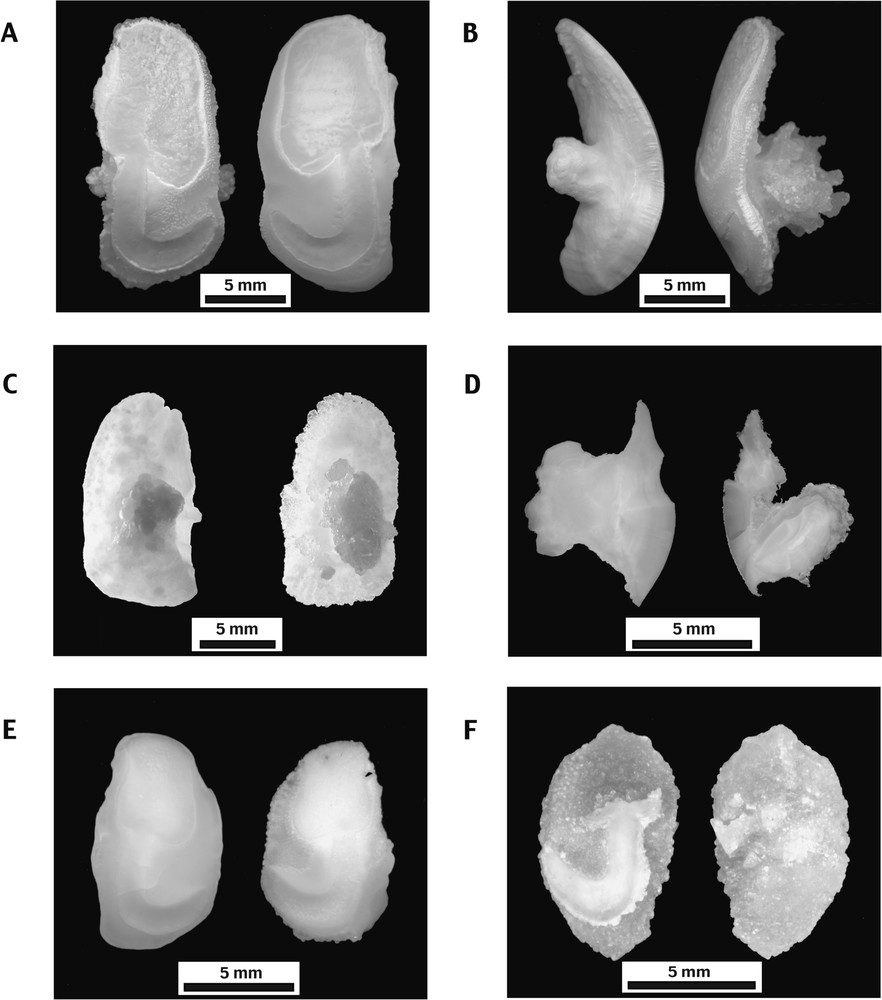

Sagittae of both species exhibit a moderately convex inner face showing a typical tadpole shaped sciaenid sulcus (Fig. 1A and E) and an outer face exhibiting a prominent, expanded, post central umbo (Fig. 1B and C). Most of the modern otoliths display an opaline colour and show a smooth, botryoidal surface. Nevertheless, in some rare cases (2.5% in Cilus gilberti, 2% in Sciaena deliciosa), one or both otoliths display a layer of translucent, euhedral crystals over their outer face. In that case, these anomalous otoliths have a rough surface. Their umbos volumetrically increase and are decorated by irregular, finger-like overgrowths (Fig. 1B and D). Although much rarer, such anomalous otoliths of C. gilberti and S. deliciosa also exist in archaeological material (Fig. 1F). In the archaeological material from southern Peru, only one anomalous sagitta of each species was discovered among the 86 C. gilberti and 891 S. deliciosa examined otoliths. However, in the field, anomalous otoliths could be overlooked because staining and preservation conditions in the sediment alter the translucent colour of their crystalline outer layer.

Otolith morphology of Cilus gilberti and Sciaena deliciosa. Cilus gilberti. (A) Medial faces of anomalous left (L) and normal right (R) sagittae (Pe-5077). (B) Ventral view of the same sagittae as (A). Note the characteristic development of the umbo, stronger on the anomalous otolith. (C) Normal left (L) and anomalous right (R) sagittae lateral faces (Pe-166). (D) Polished transverse sections of the same sagittae as (C). Sciaena deliciosa. (E) Normal left (L) and anomalous right (R) sagittae medial faces (Pe-15). (F) Medial and lateral faces of archaeological anomalous right sagitta (QLB-N3-F8). Masquer

Otolith morphology of Cilus gilberti and Sciaena deliciosa. Cilus gilberti. (A) Medial faces of anomalous left (L) and normal right (R) sagittae (Pe-5077). (B) Ventral view of the same sagittae as (A). Note the characteristic development of ... Lire la suite

Compared to the most common otoliths, the general shape of anomalous sagittae is preserved, but a loss of weight, varying between 2 and 19% (Table 1: Cl-21 and Pe-5077), was observed between right and left otoliths, whereas there is no weight difference among normal specimens of S. deliciosa [26].

Sagittae morphometry of modern Cilus gilberti and Sciaena deliciosa (mm and g)

| Species | Specimen n° | Sex | Standard length | Right otolith | Left otolith | Weight loss | ||||||

| type | length | height | weight | type | length | height | weight | |||||

| Cilus gilberti | Pe-166 | M | 447 | A | 14.66 | 8.04 | 0.401 | N | 14.64 | 8.36 | 0.473 | 15% |

| Pe-5077 | F | 905 | N | 22.4 | 11.39 | 1.713 | A | 22.43 | 10.13 | 1.679 | 2% | |

| Sciaena deliciosa | Pe-15 | M | 267 | A | 9.53 | 6.26 | 0.16 | N | 10.22 | 6.2 | 0.19 | 16% |

| Cl-14 | M | 240 | A | 9.83 | 5.64 | 0.127 | A | 9.98 | 5.59 | 0.126 | – | |

| Cl-21 | M | 236 | A | 10.0 | 5.87 | 0.132 | N | 9.88 | 5.9 | 0.163 | 19% | |

| Cl-32 | M | 249 | A | 10.51 | 6.22 | 0.172 | N | 10.27 | 6.47 | 0.201 | 14% |

3 Methods

A pair of modern otoliths of Cilus gilberti comprising a typical and an anomalous specimen, along with an archaeological anomalous right otolith of Sciaena deliciosa, was selected for X-ray diffraction analysis and scanning electron microscope (MEB) investigation.

For X-ray powder diffraction analysis, a micro-sample (

The JEOL JSM 840 A scanning electron microscope of the UFR ‘Sciences de la Terre’ of the ‘Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie’ (Paris-6), France, was used in the backscattered-electron (BSE) and secondary-electron (SE) modes. The otoliths (either bulk material or polished transverse section of modern otoliths, crosscutting the nucleus) were pasted on a graphite-coated adhesive and carbon-coated. Cathodoluminescence (CL) spectra were recorded between 200 and 900 nm, with a CL spectrometer coupled to the SEM with an aluminium-plated parabolic mirror collector, a specific cooled stage, a silica lens UV quality, a Jobin–Yvon H10.UV grating spectrometer and a Hamamatsu R636 AsGa photomultiplier [30–32]. Operating conditions were 25-kV voltage, with

4 Results

According to X-ray diffraction data, aragonite is the only CaCO3 polymorph in normal otoliths, in agreement with the only data we know for sciaenids [33]. By contrast, both calcite, aragonite and vaterite, were identified in anomalous otoliths (Table 2). Calcite and vaterite were identified in the translucent crystalline outer layer. Euhedral crystals covering the umbo of both modern and archaeological sagittae are clearly identified as calcite. Vaterite and aragonite were only detected in micro-sampling of inner face of the modern anomalous otolith.

X-ray powder diffraction analyses of calcite, aragonite and vaterite of modern (A) and archaeological (B) otoliths

| A – Modern otolith | ||||||||||||||

| Calcite | Aragonite | Vaterite | ||||||||||||

| Time counting: 1800 s | Time counting: 1800 s | Time counting: 1800 s | ||||||||||||

| d (Å) mes. | Int-v | h | k | l | d (Å) mes. | Int-v | h | k | l | d (Å) mes. | Int-v | h | k | l |

| 3.8529 | 8.0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2.3898 | 52.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4.2196 | 21.0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 3.0384 | 100.0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3.2669 | 33.0 | 3.5704 | 58.0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 2.7121 | 2.0 | 3.0253 | 3.0 | 3.2868 | 100.0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| 2.2835 | 8.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2.6968 | 24.0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2.1137 | 17.0 | |||

| 2.0965 | 4.0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2.4733 | 45.0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2.0621 | 65.0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1.9237 | 25.0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2.4056 | 13.0 | 1.8522 | 29.0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| 1.8762 | 25.0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2.3693 | 63.0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1.8181 | 89.0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| 1.6030 | 3.0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.1863 | 14.0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.6440 | 31.0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 2.1027 | 47.0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.3102 | 12.0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| 1.9741 | 100.0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1.2858 | 12.0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 1.8770 | 58.0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||

| 1.8112 | 21.0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| 1.7300 | 19.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 1.7241 | 19.0 | |||||||||||||

| 1.5557 | 11.0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 1.4963 | 10.0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||

| B – Archaeological otolith | ||||||||||||||

| Calcite | Aragonite | |||||||||||||

| Time counting: 916 s | Time counting: 2400 s | |||||||||||||

| d (Å) mes. | Int-v | h | k | l | d (Å) mes | Int-v | h | k | l | |||||

| 3.0302 | 100.0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2.3938 | 58.0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2.4913 | 5.0 | 3.2703 | 33.0 | |||||||||||

| 2.2817 | 16.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2.7271 | 8.0 | ||||||||

| 2.0918 | 10.0 | 2.6990 | 18.0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| 1.9091 | 41.0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2.4799 | 40.0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |||||

| 1.8715 | 15.0 | 2.4082 | 14.0 | |||||||||||

| 1.6012 | 7.0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.3719 | 17.0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| 1.5229 | 6.0 | 2.3391 | 54.0 | |||||||||||

| 1.4372 | 5.0 | 2.1881 | 16.0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2.1042 | 40.0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| 1.9752 | 100.0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 1.8783 | 37.0 | |||||||||||||

| 1.8124 | 19.0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||

| 1.7570 | 4.0 | |||||||||||||

| 1.7413 | 12.0 | |||||||||||||

| 1.7252 | 20.0 |

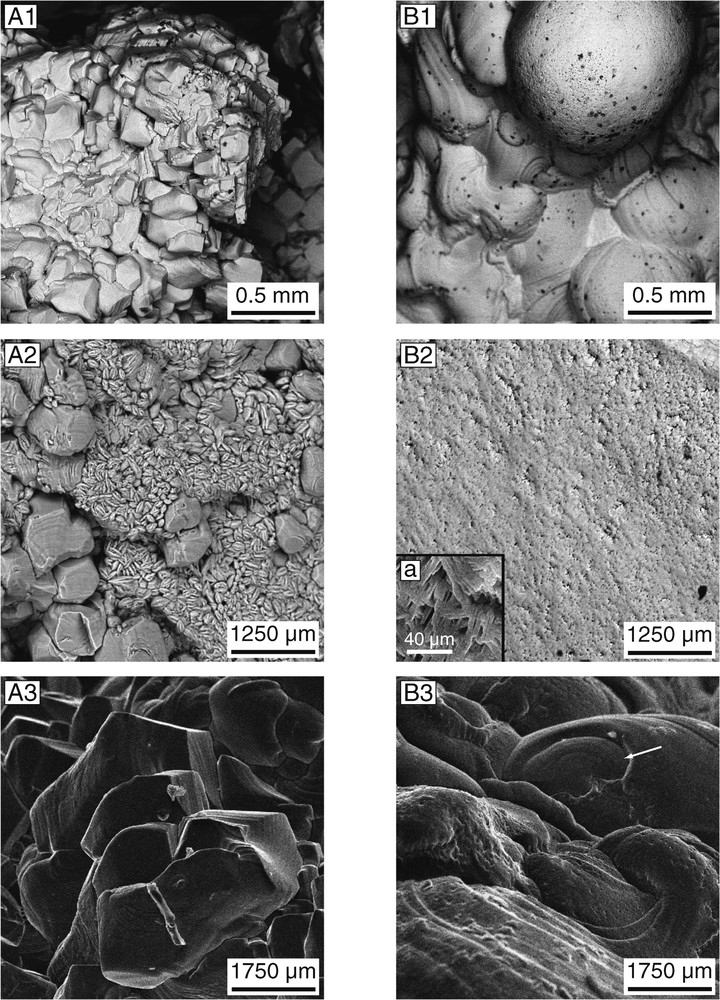

Scanning electron microscope images provide further identification clues. The aragonitic otoliths show a botryoidal surface (Fig. 2B1 and B2), which, at higher magnification, appears to be composed of successive concentric, thin layers displaying an orange skin-like surface (Fig. 2B3 and B4). By contrast, anomalous otoliths have a much more complex morphology. Calcite in the umbo of the modern and archaeological otoliths occurs as hexagonal prisms (500–700 μm) ended by a pyramid, a typical morphology of calcite from the Ge group, Phe+ subgroup [34] (Fig. 2A1, A3, and A4). The inner face of anomalous otoliths differs from that of normal otoliths by two different classes of euhedral crystals (Fig. 2A2): (1) hexagonal calcite crystals similar to those of the outer face, but of much smaller size (100–200 μm) and (2) small (50 μm), euhedral, lamellar prisms of vaterite arranged as an ‘open book’. In polished section, aragonitic normal otholiths show radial epitaxial crystal growth (Fig. 1D), as previously observed in broken sections of otoliths [10]. The cores of the anomalous otoliths preserve a similar structure that characterizes the early growth stages. Only the peripheral layers corresponding to the latest growth stages display translucent calcite (± vaterite) crystals, instead of aragonite (Fig. 1D). These observations are in agreement with those of Tomás and Geffen [13].

SEM micrographs of a modern anomalous and normal pair of Cilus gilberti otoliths. (A) Anomalous, left sagitta. A1: Umbo showing prismatic calcite crystals; A2: inner face of the same sagitta showing euhedral, prismatic calcite and tabular vaterite crystals; A3–4: detail of calcite crystals of outer face. (B) Normal, right sagitta. B1: Umbo exhibiting a typical botryoidal surface; B2: smooth inner face; a: detail showing aragonite crystals; B3: botryoidal outer face showing different aragonite layers (arrow); B4: detail of the umbo, exhibiting the typical orange skin-like surface; a: detail of a pore-like structure. All micrographs in BSE mode, except A1 and B1 in SE mode. Masquer

SEM micrographs of a modern anomalous and normal pair of Cilus gilberti otoliths. (A) Anomalous, left sagitta. A1: Umbo showing prismatic calcite crystals; A2: inner face of the same sagitta showing euhedral, prismatic calcite and tabular vaterite crystals; A3–4: ... Lire la suite

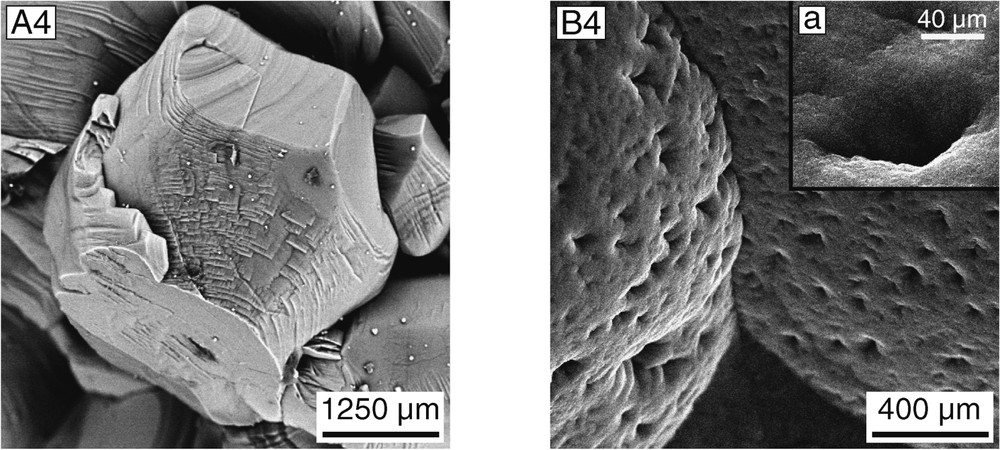

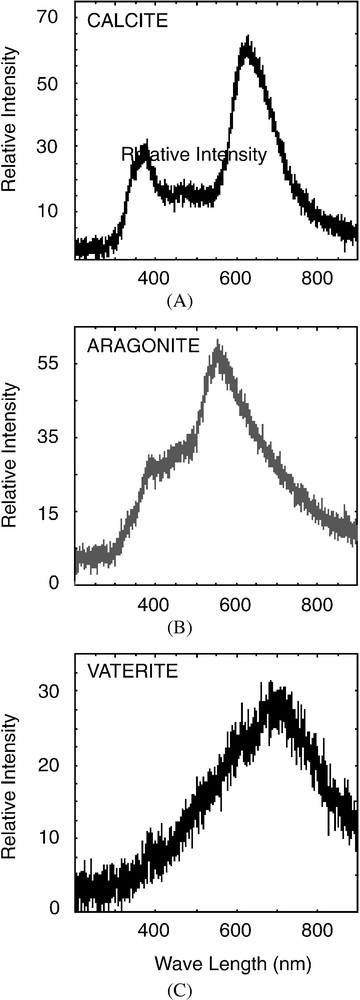

Cathodoluminescence (CL) easily discriminates between carbonate polymorphs, especially calcite and aragonite. The spectra obtained on Peruvian sciaenid otoliths display two wide bands (Fig. 3). The first band, observed at 363 nm for calcite and 380 nm for aragonite, is attributed to lattice defects [35–38]. The second band, located at 615 nm for calcite and 540 nm for aragonite, results from Ca substitution by Mn in mineral lattice, and clearly discriminates between both carbonate polymorphs [27,39].

Typical CL spectra of Mn2+ activated luminescent calcite (A), aragonite (B), and vaterite (C) of anomalous sagitta of Cilus gilberti, 200-μm spot size.

5 Discussion

The fact that calcitic overgrowths have been discovered in both modern and archaeological otoliths precludes a diagenetic origin (i.e. post mortem re-crystallization due to a diagenetic process) for calcite; single-phase calcitic otoliths have not been found and all the otholiths studied display an aragonitic core, thus indicating that otoliths invariably start growing by aragonite synthesis. Aragonite is metastable in standard geological conditions (i.e.

The scarcity of anomalous otoliths indicates that specific conditions must be met for calcite and vaterite crystals to be synthesized after a period of normal growth. Accidental and/or pathological causes are the most likely. A genetic origin can be discarded as generally only one of the two otoliths is affected, rarely both, and as, at least in our material, all otoliths have an aragonitic core. The calcification process is dependent on the endolymph chemistry and on the organic matrix [42], and it is known that alteration of the homeostasis of the endolymph may generate different forms of crystals in a single fish species [43]. This alteration could explain why the anomaly is sometimes bilateral. But the fact that an anomalous otolith can coexist with a normal one in the same fish strongly supports the assumption of an accidental cause, likely due to some dysfunction of the biomineralisation process in the inner ear. In that hypothesis, the occurrence of anomalous otoliths in both modern specimens and in archaeological populations rules out environmental modifications, for instance due to anthropic pollution, as the cause of the anomaly. Although relationships between craniofacial deformations and anomalous otoliths have been observed in reared populations of juvenile herring Clupea harengus [13], the studied fish specimens affected by malformations of the inner ear generally show no external morphological evidence. Note that this hypothetical physiological disorder mainly affects the outer faces of the anomalous otoliths and not the inner faces, which are the most important, because they are in contact with the sensory hair cells of the macula sacculi. Otoliths play an important role in hearing and balance system [44], and density differences between right and left otoliths may affect the sound perception [5]; hence a fish with a completely anomalous otolithic organ would probably not survive for long in the wild. An alternative explanation for the crystallization of calcite and/or vaterite instead of aragonite could lie in some physiological mechanisms of compensation or regeneration, similar to those involved in shell regeneration [45]. A significant weight loss characterizes all the anomalous otoliths (13.2% on average) compared to normal otoliths, whereas there is no statistical difference between right and left normal otoliths among living Sciaena deliciosa [26]. This loss is consistent with the lower density of calcite compared to that of aragonite (2.71 vs. 2.93) [46].

Another interesting observation is that anomalous otoliths have been found mainly in marine fishes; as far as we know, the only freshwater (often reared amphibiotic species) fishes displaying anomalous otoliths are a few salmonid species (Oncorhynchus mykiss, O. tshawytscha and Salvelinus namaycush) [20,47,48]. Bowen et al. [48] suggested that prevalence of anomalous otoliths might reflect stress conditions, especially among reared fishes (see also [13]). Peru is characterized by oceanic–climatic upheavals linked to the El Niño/La Niña phenomenon. Warm episodes strongly affect the Peruvian–Chilean temperate marine fauna [49], and this kind of stress might also have an impact on the otolith crystalline synthesis. It is also important to note that all the species concerned are from temperate waters, e.g., North Atlantic, South Africa, New Zealand, and Peru. In this latter country, even if the fishes mentioned here are from the intertropical zone, Peruvian waters are temperate, due to the influence of the cold Humboldt current and of the Peruvian upwelling. Hence variations in water temperature or salinity may be two controlling factors of otolith crystalline growth, although it still should be explained why the anomaly can be sometimes unilateral and sometimes bilateral. Understanding the mechanism causing this type of anomalies would help with better understanding of the biomineralisation process, and, accordingly, the species presenting these anomalies should constitute good models.

6 Conclusion

This is the first report of anomalous otoliths in Peruvian–Chilean sciaenids, both in present and archaeological specimens. The use of selected micro-sampling and SEM coupled to CL investigation reveals (1) that anomalous otoliths do preserve aragonitic cores, (2) that delicate calcite euhedral crystals cover the umbo of both modern and archaeological sagittae, (3) that vaterite is present in anomalous otoliths.

Archaeological materials provide argument against diagenetic processes, and rule out any anthropic influence. Accidental and/or pathological causes are most likely, but water temperature (or salinity) may also play a role. These parameters must be well-constrained before to use otoliths for speculating on life environment of fishes, palaeoecological environments that prevail, for example, along the south Peruvian coast 8000 years ago.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jorge Valdez who kindly sent us a large sample of Sciaena deliciosa otoliths from Antofagasta, Chile. We are grateful to Serge Miska for X-ray diffraction analyses and Omar Boudouma for his help during scanning electron microscope and cathodoluminescence analysis. This work has benefited from discussions with Philippe Blanc. Financial support was provided by the ‘Centre national de la recherche scientifique’, UMR 7160 (Paris) and UMR 8096 (Nanterre), and the ‘Mission archéologique française Pérou-Sud’.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier