Version française abrégée

L'eutypiose est une maladie particulièrement dévastatrice des vignobles dans le monde. Cette maladie vasculaire se traduit par des pertes économiques importantes, du fait de la diminution des rendements et de la réduction de la durée de vie des ceps. L'agent de cette maladie a été identifiée en 1978 par Moller et Kasimatis. Le champignon ascomycète Eutypa lata Pers. Fr. Tul & C. Tul. (initialement nommé E. armeniacae Hansf. & Carter) pénètre par les plaies de taille et envahit les tissus vasculaires des ceps et des branches, conduisant à une nécrose caractéristique brune sectorielle des tissus du bois. Après une incubation de plusieurs années, les symptômes se manifestent dans les parties herbacées, caractérisés par des sarments nanifiés et fanés, des feuilles nécrosées sur les marges, un flétrissement des inflorescences et, finalement, la mort du ceps et des branches. Une autre difficulté, si l'on veut cerner l'étendue de la maladie, vient du fait que la gravité des symptômes peut varier d'une année à l'autre, en particulier selon les conditions climatiques. Par ailleurs, diverses souches d'Eutypa lata présentent des degrés de pathogénicité différents et les différents cultivars de vigne présentent des susceptibilités à l'infection différentes.

Dans le prolongement de ces diverses remarques, le but de ce travail a été d'apporter des connaissances supplémentaires à la biologie générale du champignon dans deux directions. D'une part, une étude a été focalisée sur les effets de la température, qui est considérée comme un facteur important dans le développement des symptômes et, d'autre part, des expériences ont été menées pour déterminer les besoins nutritifs du champignon concernant les sources d'approvisionnement en carbone et azote. En corollaire et d'un point de vue plus pratique, nous avons cherché à identifier des molécules naturelles susceptibles de modifier la croissance du champignon et pouvant servir de molécules leurres dans l'optique de la mise au point d'un traitement curatif de la maladie, inexistant à ce jour.

Dans les différentes expériences réalisées, la croissance mycélienne a été mesurée sur des cultures réalisées dans des boîtes contenant un milieu nutritif de composition déterminée en sources de carbone et d'azote. Dans quelques essais, le développement fongique a été déterminé sur des cultures en milieu liquide par la détermination du poids sec de mycélium formé. Dans tous les cas, les expériences ont été réalisées, sauf indication particulière, à une température de 20 °C et dans l'obscurité.

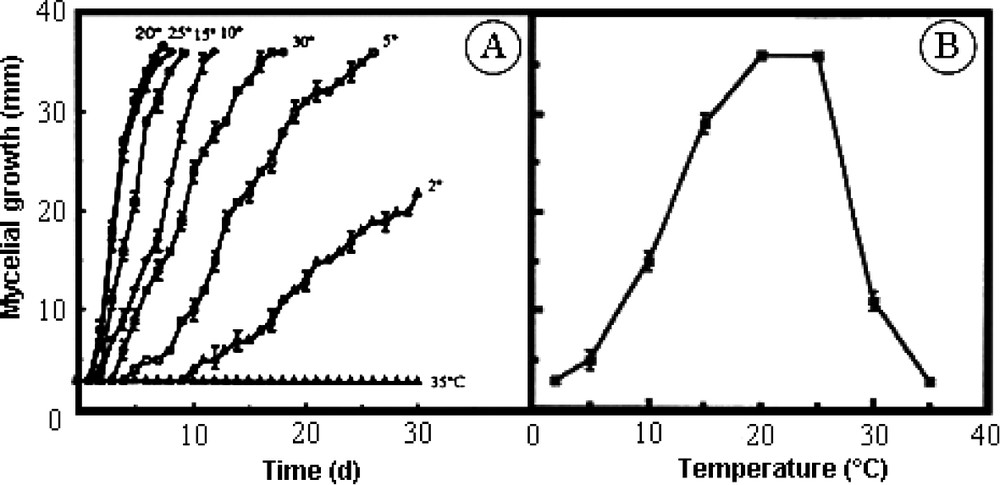

Les mesures quotidiennes de la croissance mycélienne pendant une semaine ont montré que la température optimale se situait dans une gamme de 20–25 °C. Aux températures plus basses de 15, 10 et 5 °C, la vitesse de croissance est diminuée quand la température diminue. À 2 °C, le champignon produit de nouveaux hyphes et garde des capacités vitales longtemps (plus de 20 j) à cette température. Un comportement différent est noté pour les températures élevées. Ainsi, à 35 °C, le développement est complètement inhibé et les propriétés vitales du champignon disparaissent après 21 j à cette température, puisque le mycélium n'est plus capable de croître lorsqu'il est replacé à une température de 20 °C.

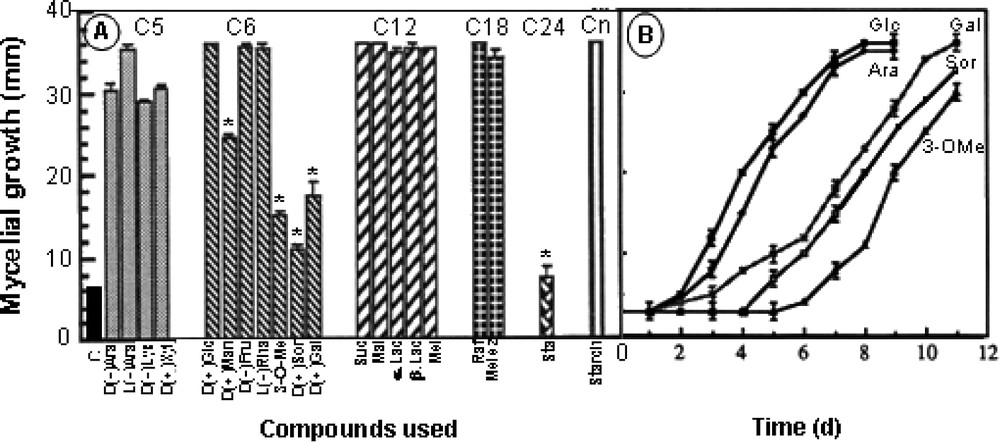

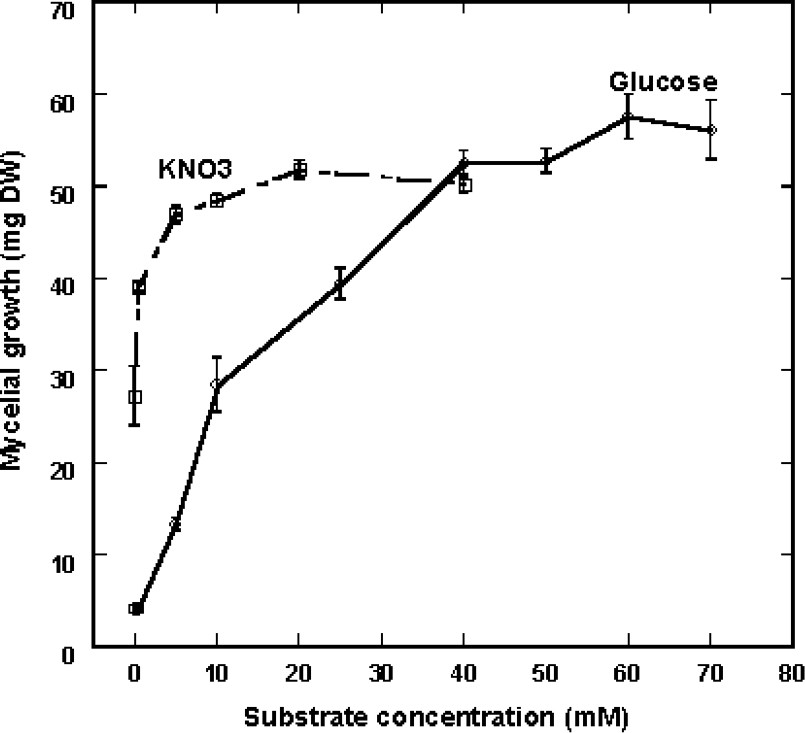

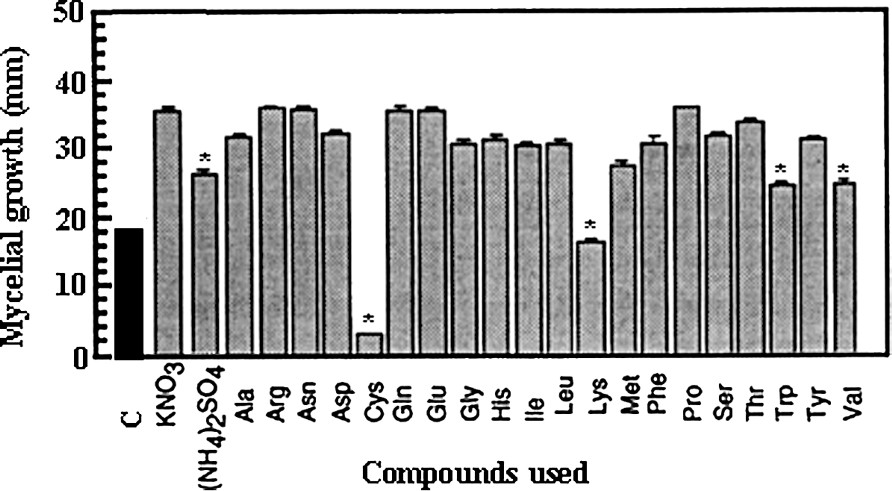

Les cultures réalisées en présence de molécules osidiques variées ont montré qu'Eutypa lata est capable d'utiliser une grande variété de sources de carbone pour ses besoins nutritifs, en présence de KNO3 comme source d'azote. Le développement est ainsi possible en présence de sucres en C5 (arabinose, lyxose, xylose), en C6 (glucose, mannose, fructose, rhamnose, 3-O-methylglucose, sorbose, galactose), en C12 (saccharose, maltose, lactose, mélibiose), en C18 (raffinose, mélézitose), en C24 (stachyose) et Cn (amidon soluble). Certains sucres (galactose, 3-O-methylglucose, sorbose et stachyose) retardent cependant le début de la croissance mycélienne sans altérer le degré final du développement. Avec le glucose, il a été montré qu'une concentration utile pour une bonne croissance du champignon se situe au delà de 40 mM. De la même manière, 20 amino acides et deux sels ont été testés comme source d'azote en prenant le glucose comme source de carbone. Avec KNO3, on note une augmentation de la croissance en fonction de la concentration appliquée, une concentration optimale étant atteinte pour une valeur de 10 mM. La plupart des acides aminés naturels sont bien utilisés pour la croissance mycélienne ; en particulier, la proline assure une croissance très homogène du mycélium et, de ce fait, a aussi été utilisée comme source d'azote équivalente au KNO3. Des résultats moins favorables ont cependant été obtenus avec la lysine, la méthionine, la valine et le tryptophane, qui diminuent la vitesse de croissance mycélienne. L'addition de proline rétablit la capacité optimale de croissance, indiquant que l'effet de ces acides aminés peut être attribué à un défaut d'utilisation métabolique. Beaucoup plus spectaculaire est le résultat obtenu avec la cystéine, qui inhibe complètement le développement fongique pour une concentration de 10 mM ; cet effet n'est pas inversé par addition de proline, ce qui indique une action antifongique réelle de cet acide aminé soufré.

En conclusion, nos observations ont montré que la température expérimentale agit de manière différenciée sur le développement d'Eutypa lata : le champignon s'acclimate bien aux températures basses (2 °C) mais résiste moins bien aux températures élevées (35 °C). Cette observation demande à être corrélée aux observations étiologiques réalisées dans le vignoble. Bien que certaines molécules osidiques ne favorisent pas le développement du champignon, celui ci s'adapte bien pour trouver les mécanismes nécessaires à l'assimilation de sucres de structure particulière et considérés comme non métabolisables. De ce fait, il apparaît peu judicieux de s'adresser à ce type de molécules pour assurer la fonction de leurre métabolique. Au contraire, les résultats obtenus avec la cystéine peuvent permettre d'envisager la mise au point d'un traitement curatif avec cette molécule, puisque cet amino acide naturel peut être transporté à longue distance dans la plante jusqu'au site colonisé par le champignon et absorbé par la cellule fongique par des transporteurs spécifiques.

1 Introduction

Eutypa dieback, also known as ‘dying arm disease’ or ‘eutypiosis’, is one of the most devastating diseases to be found in many grape-producing areas around the world. This disease is responsible for serious economic losses [1,2], as a consequence of decreased yields and reduced longevity of grapevines. The causative agent of this disease was identified by Moller and Kasimatis in 1978 [3]. The ascomycete Eutypa lata Pers. Fr. Tul & C. Tul. (initially named E. armeniacae Hansf. & Carter) infected plants primarily through pruning wounds. The fungus then invades the vascular system of the trunk and shoots, leading to a characteristic dark and wedge-shape necrosis of woody tissues. After an incubation period of three or more years [4], particular symptoms appear in the herbaceous parts of plants characterized by dwarfed and withered shoots, marginal necrosis of the leaves, dryness of inflorescences, and, finally, shoot death.

Another difficulty in identifying the extent of disease lies in the fact that the degree of symptoms varies from one year to another, depending, in particular, on the climatic conditions [5]. For example, a mild and wet spring favours the extent of the symptoms. Moreover, different strains of Eutypa may present various degrees of pathogenicity [6] and there are significant differences in susceptibility to infection between the vine race cultivars; for example, Cabernet-Sauvignon is particularly sensitive whereas Merlot is tolerant [7].

The aim of this paper is to get a deeper insight into knowledge of the general biology of the pathogenic fungus. The work has thus evolved in two directions. Firstly, among active factors, temperature is said to affect the development of symptoms. Certain characteristics of its action on the mycelial growth were therefore investigated. Secondly, a more practical aspect was to try to identify natural molecules able to modify mycelial growth. The purpose of this approach was to find inhibitory compounds absorbed and assimilated by the fungus either as nutritional bait or as fungicidal metabolites. In this respect, various sugars and natural amino acids were tested. Among results of interest, it is to be stressed that cysteine presented a very marked antifungal effect, allowing a practical approach to the fight against this pathogenic fungus to be envisaged.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Fungal growth conditions

The strain of Eutypa lata Pers. Fr. Tul. & C. Tul. used in these experiments was isolated from necrotic wood in a vineyard near Poitiers (Biard, France) showing symptoms of Eutypa dieback. The strain (referenced BI1) was grown on a sterile culture medium solidified with agar (20 g l−1). The growth medium was yeast nitrogen base minimal (YNBm, Difco, Detroit) at 1.7 g l−1, supplemented with glucose (10 g l−1) as carbon source and KNO3 (4 g l−1) or proline (5 g l−1) as nitrogen source.

2.2 Mycelial growth conditions

Mycelial growth in the various experiments was measured on cultures made in wells (33-mm diameter), containing the solid medium (agar, YNBm, carbon source, nitrogen source) fixed at pH 5.5 with 10 mM MES/KOH, the value previously shown to be the most convenient for fungal development [8]. The experiments were carried out in the dark at 20 °C, unless otherwise indicated. The inoculum consisted of a 3-mm diameter mycelial disk taken from a solid culture by means of a cork-borer. The diameter of the mycelium was measured daily in six identical wells for 8 days. This is the period necessary for the well to be invaded completely in the control sets.

In assays devoted to quantitative determination of nutritional requirements, mycelia were grown in 10-ml flasks in liquid medium with the same composition as above for solid medium, except that agar was omitted. Flasks were inoculated with a 3-mm diameter mycelium disk taken from a solid culture. At a given time, mycelium was filtered, dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h and weighed.

The media were autoclaved under 0.5 bar at 120 °C for 15 min. Compounds were added during cooling at 50 °C at the desired concentration. Stock solutions prepared at a 100-mM concentration in distilled water were sterilized by membrane filtration (0.22-μm pore size). Care was taken to verify that the pH of the culture medium was not modified when the tested compounds were added.

For each type of assay, experiments were conducted at least three times.

2.3 Chemicals

Sugars and amino acids were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chimie (Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France).

3 Results

3.1 Effect of temperature

Results shown in Fig. 1A present the time course of mycelial growth in our experimental conditions as a function of experimental temperature. Optimal growth was achieved between 20–25 °C. This range of temperature appears to be the most appropriate for fungus development. In this case, mycelial development became visible on the first day after inoculation on the growing medium and clearly measurable on the second day. The delay noted is attributed to initiation of growth of new hyphae after wounding made during the harvesting of the inoculum. At 15, 10 and 5 °C, the mycelial growth was correspondingly reduced as indicated by the increasing latency period and by the decreasing slope of the representative curves. Even at 2 °C, Eutypa lata clearly produced new hyphae and remained alive at this low temperature. Indeed, if cultures were put back at 20 °C after 20 days at the low temperature, a normal growth was restored after a latency of 8 days (data not shown). A very different behaviour was observed at higher temperatures. The ability to develop was reduced at 30 °C and disappeared completely at 35 °C, since no growth occurred even after 30 days. Fig. 1B shows the data a week after the beginning of the experiment, illustrating the above-described general observations.

Effect of temperature on the mycelial development of Eutypa lata. A. Time course of mycelial growth on solid culture medium at the indicated experimental temperature. B. Recapitulative results of the experiment with calculations made after a 6-day period (mean ± SE; n=18).

In order to determine the duration during which the fungus remained viable at 35 °C, cultures were withdrawn from this high temperature and replaced at various time to 20 °C. Fig. 2 shows that growth was unmodified compared to controls when thermal transfer was made after 3 days at 35 °C. After 7 days at this temperature, the growth rate was unchanged but more time was needed for regrowth to occur. This was particularly visible after 14 days, since the latent period increased to 5 days. The most spectacular result was that reversibility completely disappeared when transfer was made after 21 days at 35 °C.

Effect of exposure duration at 35 °C on the mycelial development of Eutypa lata. At a given time (V), the fungus on the solid culture medium was put back at 20 °C. The experiment has been carried out three times with similar result.

3.2 Nutritional requirements for mycelial growth

In these experiments, the carbon source and the nitrogen source were added in the YNBm/MES medium at pH 5.5.

The data in Fig. 3A, with 20 osidic molecules at a 50-mM final concentration, showed that Eutypa lata is able to use a great variety of carbon sources for its growth needs in the presence of 40 mM KNO3 as sole nitrogen source. Mycelial development was not affected in general by sugars in C5 (arabinose, lyxose, xylose), C6 (glucose, mannose, fructose, rhamnose), C12 (sucrose, maltose, lactose, melibiose), C18 (raffinose, melezitose), C24 (stachyose) and Cn (soluble starch). Very constant growth was obtained with glucose and a small growth hindering was observed following feeding with some sugars in C6 (galactose, 3-O-methylglucose, sorbose) and with stachyose (C24). The curves in Fig. 3B show that this delay affected the beginning of growth process, but not the final degree of development. Additional experiments were carried out in order to determine the influence of nutrient concentration in a range of 0.5–70 mM glucose in the presence of 40 mM KNO3 as nitrogen source. The experiments made on the solid medium were not suitable to quantify the process, since a residual growth was seen in the low-concentration range (0–0.5 mM), depicted by very thin hyphae growing at the same rate as mycelium grown on higher glucose concentration. In these conditions, this residual growth may be ascribed to the use of nutrients stored in the inoculated hyphae. However, in this case, the density of the culture was considerably much lower, so that quantifying by diameter measurement did not reflect reality. Cultures were therefore made on liquid medium and fungus development was measured by weighing mycelium developed for 10 days. Fig. 4 shows that mycelial growth greatly increased with substrate concentration at up to 40 mM glucose. Above this value, growth was scarcely affected, so that a 50-mM final concentration was chosen in the experiments.

Effect of various osidic molecules applied at 50 mM on the mycelial growth of Eutypa lata on a solid culture medium supplemented with 40 mM KNO3. A. Recapitulative results with calculations made after a 7-day period. C: control; Ara: arabinose; Lyx: lyxose; Xyl: xylose; Glc: glucose; Man: mannose; Fru: fructose; Rha: rhamnose; 3-O-Me: 3-O-methylglucose; Sor: sorbose; Gal: galactose; Suc: sucrose; Mal: maltose; Lac: lactose; Mel: melibiose; Raf: raffinose; Melez: melezitose; Sta: stachyose; St: soluble starch. B. Time course of mycelial growth after feeding with galactose, sorbose and 3-O-methylglucose (mean ± SE; n=18). (*: statistically different from Glc at P<0.01 by the Student–Fisher test.)

Effect of increasing glucose concentrations with KNO3 applied at 40 mM and of increasing KNO3 concentrations with glucose applied at 50 mM on the mycelial growth of Eutypa lata observed in liquid culture medium. Calculations were made after a 10-day treatment (mean ± SE; n=9).

In order to determine the most convenient nitrogen sources for fungus growth, every compound was used at 40 mM in the culture medium containing 50 mM glucose as sole carbon source. As seen in Fig. 5, KNO3 was better used than ammonium sulfate and among the 20 natural amino acids, 16 were a suitable nitrogen source. In particular, proline gave very homogenous results and, therefore, can be used equivalent to KNO3. Following the same procedure (liquid medium) and for the same reason as for sugars, the influence of KNO3 concentration was also defined on fungal development capacity. In our experimental conditions, mycelial growth reached an optimal value at a 5-mM concentration (Fig. 4). It can be noted that the requirement of nitrogen source was considerably lesser than that necessary with glucose.

Effect of various nitrogen sources applied at 40 mM on the mycelial growth of Eutypa lata in a solid culture medium supplemented with 50 mM glucose. Calculations were made after a 7-day period (mean ± SE; n=18). (*: statistically different from KNO3 at P<0.01 by the Student–Fisher test.)

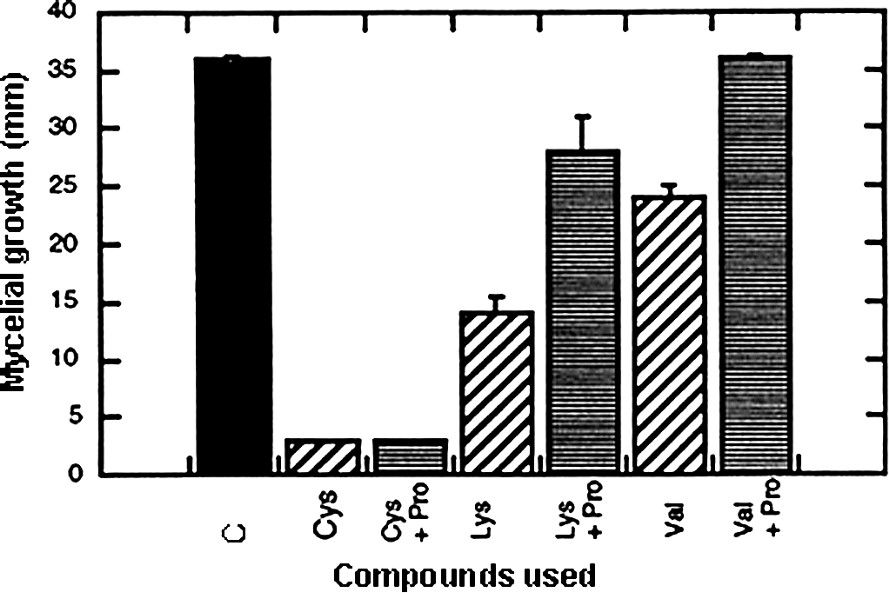

In the scope of our preoccupations, interesting data came from lysine, methionine, valine and tryptophan that reduced the fungal growth rate. However, the most fruitful observation was that cysteine induced complete inhibition in growth. In order to determine whether these effects were the results of specific action or simply due to an inappropriate use of the compound (for example, a problem in absorption), a complementary supply of nitrogen source (in occurrence, 40 mM proline) was given on the sets treated with the inhibitory amino acids. Fig. 6 shows that the effect induced by cysteine was a true inhibition, whereas the action of valine can be ascribed to metabolic starvation. The conclusion was less clear concerning lysine, since no complete reversion of the inhibitory effect was obtained.

Effect of cysteine, lysine and valine applied at 40 mM on mycelial growth of Eutypa lata and reversion of the induced hindering effect by an additional supply of proline at 40 mM. Calculations were made after a 7-day period (mean ± SE; n=18).

4 Discussion

A particular characteristic in Eutypa dieback is that symptoms can vary on the same stock from one year to another. This symptomatology may be linked to variations in fungus development in the host plant in relation to changes in its climatic environment. Knowledge of the physiological conditions favourable to its development enables this behaviour to be understood in part and the disease extent to be predicted.

In this direction, dealing with the fungus sensitivity to temperature, our results showed that E. lata is able to grow optimally in a large range of temperatures without much difference between 15–30 °C. Cold conditions from 10 to 2 °C only induced delay in growth. Prolonged exposure at 2 °C showed that this treatment did not modify the vital capacity of the fungus. In this direction, it had been shown that spores of E. lata germinated after an incubation at −20 °C [9]. By contrast, prolonged exposure at high temperature (35 °C) inhibited mycelial development completely, and even, following a 2-week treatment, brought about death of the mycelium. It appears therefore that hot summers may be unfavourable to fungus development. This laboratory study has now to be correlated with etiology in the vineyards.

The second part of our study dealing with the nutritional requirement showed that this fungus is able to develop using a large variety of carbon sources. It can grow using very different and particular carbon hydrates as a unique source of nutrient. Nevertheless, some osidic molecules did not favour mycelial growth, e.g., methylglucose, stachyose. This can be due to either reduced ability to absorb the molecule or to the fact that the compound may not be immediately metabolizable, thus disturbing some vital physiological processes. However, rapid adaptation occurred, shown by restoration of growth in the presence of these very particular sugars. Likewise, it was verified that E. lata is able to assimilate a very large variety of natural amino acids as a unique supply of nitrogen source. Compared to glucose, the nutritional requirement in nitrogen source is considerably lesser (10 times expressed in molarity). Among amino acids, only a few were less efficient for mycelial development: lysine, methionine, tryptophan, and valine. As with sugars, further experiments will establish whether this effect is linked to poor absorption or to a particular effect on a specific mechanism.

Our most interesting result in the scope of our aim is that cysteine in a millimolar range showed antifungal properties. This observation has to be generalized to other strains of E. lata isolated from other vineyards and extended to other fungi intervening in other grapevine diseases. In this direction, it has already been shown that cysteine inhibited spore germination of some fungal weed pathogens in Alternaria species [10] and hindered mycelial growth in Botrytis cinerea [11] and in the basidiomycete Inonotus obliquus [12]. Moreover, according to experiments carried out on dermatophytes [13,14], cysteine can be used as an effective control agent against fungal diseases in animals and human beings.

The antifungal effect observed on E lata may be fruitful in the context of a curative treatment of the disease. As for other amino acids [15, and references therein], this sulfured compound can be naturally transported over a long distance in plants and absorbed by the fungal cells through an active mechanism implying proton-dependent co-transport system as shown in Neurospora crassa and Penicillium chrysogenum [16,17]. Moreover, this uptake may have a specific component since involvement of carriers specifically implied in amino acid absorption has been characterized in Neurospora crassa [18]. This last aspect is being analysed currently.

5 Conclusion

The data presented here show that temperature affects differentially mycelial growth of Eutypa lata: the fungus adapts to a low temperature (2 °C), whereas it did not resist to a high temperature (35 °C). This can be related to the observation made in vineyards, showing that symptoms are reduced after warm summers. The fungus is able to use numerous osidic molecules and has a high degree of adaptation to assimilate sugars with particular structure considered as non-metabolizable. Consequently, one cannot envisage using this type of compound as nutritional bait. By contrast, this role can be devoted to cysteine, which appears to have an inhibitory effect on the mycelial development and therefore may be envisaged as a candidate for a curative control of the disease.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by the ‘Conseil interprofessionnel du vin de Bordeaux’.