Version française abrégée

Les scorpions humicoles sont globalement rares. Le premier cas décrit avec précision a été Akentrobuthus leleupi Lamoral, 1976, un micro-Buthidae découvert dans les forêts de la Province du Kivu au Congo. Peu de temps avant la description d'A. leleupi, un autre genre et espèce nouveaux, Lychasioides amieti Vachon, 1974, avaient été décrits de la forêt d'Otomoto au Cameroun. Selon le collecteur de cette espèce, elle a été trouvée dans des sols organiques, pouvant ainsi être considérée comme un élément humicole. Plus récemment, un nouveau genre, Microcharmus Lourenço, 1995, composé uniquement de vraies espèces humicoles, a été décrit de Madagascar. La découverte de plusieurs espèces nouvelles et même d'un deuxième nouveau genre a permis d'isoler ce groupe de micro-scorpions dans une famille à part, celle des Microcharmidae Lourenço, 1996. Par la suite, un troisième genre Ankaranocharmus Lourenço, 2004 a été ajouté à la famille des Microcharmidae. En ce qui concerne les espèces humicoles d'Amérique tropicale, celles-ci semblent être encore plus rares que celles d'Afrique et de Madagascar. Seul un genre et une espèce, Microananteris minor Lourenço, 2003, ont été découverts depuis peu en Guyane française. À présent, une nouvelle espèce de micro-scorpion Buthidae humicole, Ananteris cryptozoicus sp. n., est décrite de l'Amazonie brésilienne.

Les genres de la sous-famille Ananterinae ; leur possible évolution depuis le milieu endogé vers le milieu épigé

La sous-famille des Ananterinae a été tout d'abord suggérée par Pocock (1900) pour accommoder le genre Ananteris. Par la suite, la question de la validité de cette sous-famille a été reprise par différents auteurs, entre autres Kraepelin (1905), qui l'accepte, et Birula (1917), qui la refuse. Le dernier auteur à discuter de la question des Ananterinae a été Mello-Leitão (1945), mais dans tous les cas, seul le genre Ananteris a été considéré.

Dans une publication plus récente, Lourenço (1985) place le genre africain Ananteroides Borelli, 1911 en synonymie du genre Ananteris, définissant ainsi un modèle de distribution gondwanien pour ce genre. Des études plus approfondies sur le genre Tityobuthus Pocock, 1893, endémique de Madagascar, attestent les affinités de ce dernier avec le genre Ananteris. Ceci est suivi de la description du genre Himalayotityobuthus Lourenço, 1997, endémique de l'Himalaya, genre également apparenté au genre Tityobuthus. Finalement, une re-analyse du genre africain Lychasioides atteste également les affinités de ce dernier avec les genres Ananteris et Tityobuthus.

L'association de tous ces genres au sein de la sous-famille des Ananterinae conforte l'existence d'un modèle de distribution gondwanien. De plus, la récente découverte de formes fossiles dans l'ambre de la Baltique, notamment Palaeotityobuthus Lourenço & Weitschat, 2000 et Palaeoananteris Lourenço & Weitschat, 2001, également apparentés aux genres Tityobuthus et Ananteris, confirment ce modèle de distribution, mais également l'ancienneté de la lignée représentée par les Ananterinae.

Plusieurs traits morphologiques démontrent les possibles relations entre ces scorpions : petite taille, persistance des caractères néothéniques à l'âge adulte et, dans la majorité des cas, un comportement cryptique. Presque rien n'est connu sur leur biologie et écologie, mais les inventaires réalisés depuis 25 ans environ montrent que le nombre d'espèces est bien plus important que celui prévu initialement. Pour les Ananteris, le nombre d'espèces a progressé de 3 à 28, tandis que, pour le Tityobuthus, ce nombre est passé de 1 à 16. Cependant, dans tous les cas, les espèces sont rares et présentent des aires de répartition très limitées. Des mâles sont connus pour environ 50% des espèces et, au moins pour une espèce, la parthénogenèse a été démontrée. Cette forme de reproduction asexuée pourrait être une compensation à l'absence des mâles.

Une autre caractéristique des genres Ananteris et Tityobuthus, est l'absence des formes juvéniles lors de collectes par des méthodes classiques telles la chasse à vue, le piégeage ou même l'utilisation de lampes UV. Seules les méthodes d'extraction telles celles du Berlese, Winkler et Kempson ont permis la collecte de juvéniles. L'utilisation de l'extraction par Berlese a même permis la collecte d'un nouveau genre d'Ananterinae, Microananteris minor. Une question peut alors être posée : pourquoi des formes juvéniles d'espèces épigées sont exclusivement collectées par des méthodes d'extraction ?

Les scorpions ont évolué à partir des milieux aquatiques vers les milieux terrestres entre le Carbonifère et le Trias. Il est très possible que des formes intermédiaires aient existé, même si elles sont difficiles à identifier dans les registres fossiles. Dans tous les cas, les premières formes terrestres devaient être inadaptées pour vivre dans des milieux extrêmes tels les savanes ou les déserts, à présent bien colonisés par les scorpions. En fonction d'une adaptation plus ou moins réussie aux milieux terrestres, le milieu endogé apparaît comme un très bon compromis dans les premiers stades évolutifs d'un groupe comme celui des scorpions. La capacité d'évaporation de l'air est le facteur physique le plus important du milieu environnant qui affecte la distribution des animaux cryptozoïques, ceci étant directement associé à la grande surface corporelle des petites espèces en rapport avec leur masse. La conservation de l'eau est le premier problème pour la survie de ces espèces. La majorité des animaux cryptozoïques vit dans des milieux saturés en eau, même si ces derniers ne doivent pas être trop humides, pour éviter toute inondation. Il est très probable que l'évolution de nombreuses formes d'invertébrés de la vie aquatique à la vie terrestre a dû passer par la vie dans le sol, où la respiration aérienne n'est pas associée avec la perte d'eau.

L'actuelle situation écophysiologique des scorpions appartenant aux Ananterinae pourrait suggérer que cette lignée ait été à l'origine composée exclusivement de formes endogées. Au cours du temps évolutif, les formes adultes auraient appris à explorer le milieu épigé, mais les formes juvéniles seraient restées endogées. Ce tableau est fréquemment observé chez les insectes, mais inconnu chez les scorpions. Cette hypothèse pourrait être une explication possible à l'absence de formes juvéniles en dehors du milieu endogé.

1 Introduction

Humicolous scorpions are universally rare. The first example to be precisely reported was that of Akentrobuthus leleupi, a buthid found in forests of the Kivu Province in Congo and described by Lamoral [1]. Just before the publication of this, Vachon [2] had described a new genus and species, Lychasioides amieti, from the forest of Otomoto in Cameroon. According to the collector of this species, it was also to be found in organically rich soils. It was therefore considered as humicolous (Vachon, in litt.). More recently, a new genus of true humicolous buthid scorpions, Microcharmus, has been described from Madagascar [3]. With the discovery of several new species and a second new genus, this group of micro-scorpions has been accommodated in its own family Microcharmidae [3–7]. Subsequently, a third genus Ankaranocharmus Lourenço [8] was also described in the family Microcharmidae.

Tropical American species of humicolous scorpions appear to be even rarer than those found in both Africa and Madagascar. Only a single genus and species, Microananteris minor Lourenço has recently been described from French Guiana [9]. In the present paper, a new species of humicolous buthid scorpion is described from Brazilian Amazonia. Although certain morphological characters could, to some extent, associate it with the genus Microananteris, the position of the median eyes, and the structure of the telson suggests that the new species should be accommodated in the genus Ananteris. It is suggested that some of the morphological features of the new species may be an adaptation to the soil dwelling life of these humicolous scorpion. The new species described here represents the second humicolous scorpion to be reported in the Neotropical region.

2 The genera within the subfamily Ananterinae and their possible evolution from endogeous to epygean environments

The subfamily Ananterinae was first proposed by Pocock [10] to accommodate the genus Ananteris Thorell. Pocock wrote as follows: “I propose to eliminate from this subfamily (Buthinae) the isolated Neotropical genus Ananteris, which differs strikingly from the rest of the family in the structure of the pectines. The subfamily Ananterinae may be created for its reception.” Subsequently, the matter of the subfamily Ananterinae was discussed by several authors, in particular by Kraepelin [11], who accepted the proposal, and by Birula [12], who rejected it. The last author to discuss the issue in detail was Mello-Leitão [13], but in every case Ananterinae was considered only in relation to the genus Ananteris. In a paper dealing with genera Ananteris and Ananteroides Borelli from Africa, Lourenço [14] proposed the synonymy of the monotypic genus Ananteroides with Ananteris, defining in this way a typical Gondwanaland pattern of distribution for Ananteris. In more recent publications, Lourenço [3,4] reopened the study of the Malagasy genus Tityobuthus Pocock, and suggested clear affinities that it had with the genus Ananteris. This was followed by the description of a new genus, Himalayotityobuthus Lourenço [15], from the Himalayas, which was clearly associated with the genus Tityobuthus from Madagascar. In another paper Lourenço [16] also suggested the affinities of the African genus Lychasiodes Vachon, with both Ananteris and Tityobuthus.

The association of all these different genera within the subfamily Ananterinae clearly indicates a Gondwanian pattern of distribution for this undoubtedly ancient lineage of buthid scorpions. The recent discovery of fossil forms in Baltic amber, namely Palaeotityobuthus and Palaeoananteris Lourenço & Weitschat, which are closely related to Ananteris and Tityobuthus added further confirmation of both the Gondwanian pattern of distribution and antiquity of the Ananterinae lineage [17,18].

The morphological traits of these genera of scorpions demonstrate their relationships. These are: small size, the persistence of neotenic structures in the adults and, in most instances, cryptozoic behaviour – as well as the existence of some humicolous species. Their ecology and biology are poorly known, but detailed inventories carried out during the last 25 years, have shown that the number of species is significantly greater than was initially expected. During this period the number of known species increased from 3 to 28 in Ananteris and from 1 to 16 in Tityobuthus. These species are, however, invariably extremely rare and present very limited and patchy ranges of distribution. According to Lourenço & Cuellar [19], when all the known species of Ananteris are combined, they are represented by less than 200 specimens in all. Males have been found for only about 50% of the species, and parthenogenesis has been demonstrated in at least one [19], suggesting that this asexual form of reproduction may compensate for the absence of males.

Another particularity of both the genera Ananteris and Tityobuthus, is the absence of juvenile forms from collections. These have been based mainly on overturning rocks and the use of ultraviolet light and pit-fall traps. Only the use of extraction methods, such as those of Berlese, Winkler and Kempson, has resulted in the collection of juvenile forms. Extraction methods also led to the discovery and description of a new humicolous genus and species of Ananterinae Microananteris minor [9]. These methods have been used even more in Madagascar than in the Neotropics, and have resulted in the collection of juvenile forms of Tityobuthus. One question can therefore be addressed: why are the juvenile forms of these crypzoic but epygean species only found by extraction methods?

Scorpion became adapted to terrestrial environments between the Carboniferous and Triassic periods [20,21]. It is quite possible that transitional forms may have existed then, although these are difficult to identify [20]. In every case, the early terrestrial forms would have been unable to survive in extreme environments such as savannas and deserts that are today colonized by numerous species. According to their degree of adaptation to life on land, different types of soil would have been utilized by different stages of the evolution and adaptation of early scorpions. The evaporating power of the air is the most important physical factor of the environment affecting the distribution of cryptozoic animals. This is because small creatures have a very large surface in proportion to their mass; consequently, the conservation of water is the prime physiological problem of their existence [22–24]. The majority of cryptozoic animals are restricted to moist conditions, although these must not be so wet that they engender waterlogging. It is probable that the evolutionary transition of many invertebrates from aquatic to terrestrial life may have taken place via the soil where aerial respiration is not associated with desiccation [22–24]. The present eco-physiological situation of the scorpions belonging to the Ananteridae could suggest that this lineage was originally exclusively composed of soil dwellers. During evolutionary time adult forms learned to explore the epygean environment, but juveniles remained endogean. This kind of situation is frequently observed in insects, but unknown among scorpions in general [25,26]. This could be a possible explanation for the absence of juveniles outside the soil environment.

3 Taxonomic treatment

Family Buthidae C.L. Koch, 1837

Subfamily Ananterinae Pocock, 1900

Genus Ananteris Thorell, 1891

Ananteris cryptozoicus sp. n. (Figs. 1–7)

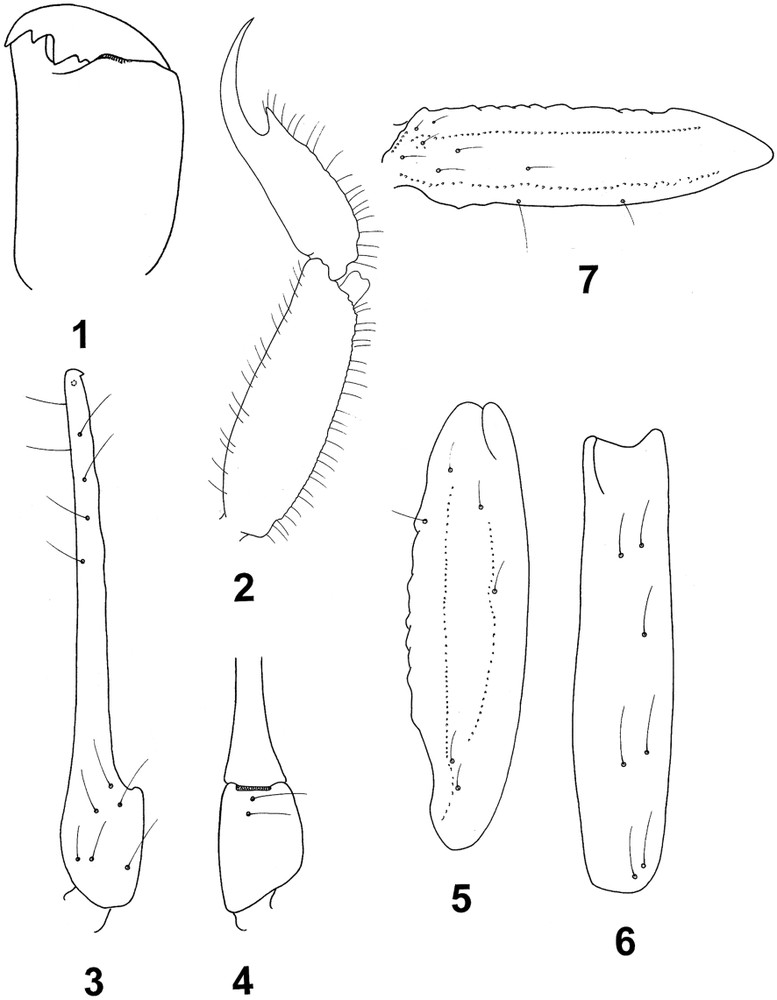

Ananteris cryptozoicus sp. n. Male holotype. 1. Chelicera, dorsal aspect. 2. Metasomal segment V and telson, lateral aspect. 3–7. Trichobothrial pattern. 3–4. Chela, dorso-external and ventral aspects. 5–6. Patella, dorsal and external aspects. 7. Femur, dorsal aspect.

Type-material. Male holotype. Brazil, State of Amazonas, Rio Tarumã-Mirím area (nearby Manaus); secondary upland forest (Capoeira) in organic soil (soil extraction by the Kempson method), 26/V/1983-K18TM (J.M.G. Rodrigues & J. Adis leg.). No paratypes. Deposited in Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia (INPA), Manaus, Brazil.

Etymology. The specific name makes reference to the cryptozoic behaviour of the new species.

Diagnosis. Very small scorpions, when compared with the average size of most species of micro-buthid genera, and measuring 10.81 mm in total length (see morphometric values). It can be readily distinguished from all the other species of the genus Ananteris Thorell, and in particular from those distributed in the region of Manaus by (i) very small size, (ii) extremely pale yellow coloration throughout the body and appendages, without any spots, (iii) median eyes in a markedly anterior position in relation to the centre of the carapace, (iv) inconspicuous carinae over the body and appendages, (v) carapace with a thin but intense granulation, (vi) tibial spurs reduced. This new humicolous species is possibly an endemic element to the soils of the humid forests of the region of Manaus.

Description. Coloration. Basically yellowish throughout; metasoma, pectines, and appendages paler than the body. Only median and lateral eyes are surrounded by black pigment.

Morphology. Carapace with thin but intense granulation; anterior margin almost straight. Carinae and furrows inconspicuous. Median ocular tubercle distinctly on the anterior third of the carapace; median eyes separated by approximately one and half ocular diameters. Three pairs of lateral eyes. Sternum pentagonal. Mesosoma: tergites weakly granular. Median carina weak in all tergites. Tergite VII pentacarinate. Venter: genital operculum divided longitudinally, each plate having a more or less triangular shape. Pectines large: pectinal tooth count 18–18; basal middle lamellae of the pectines not dilated; fulcra absent. Sternites smooth with short semi-oval spiracles; VII with a few granulations and vestigial carinae. Metasoma: segment I with 10 carinae, crenulated; segments II to IV with 8 carinae, weakly crenulate. Intercarinal spaces weakly granular; almost smooth. Segment V with 5 carinae. Telson with a very elongated ‘pear-like’ shape, almost smooth with one ventral carina; aculeus long and not strongly curved; subaculear tooth strong and spinoid. Cheliceral dentition characteristic of the family Buthidae [27]; fixed finger with two moderate basal teeth; movable finger with two very weak basal teeth; ventral aspect of both finger and manus with dense, long setae. Pedipalps: femur pentacarinate; patella and chela with a few vestigial carinae; internal face of patella with some 5–6 vestigial granules; all faces weakly granular, almost smooth. Fixed and movable fingers with 5–6 almost linear rows of granules; at least one accessory granule present at the base of each row; extremity of movable fingers with two accessory granules. Trichobothriotaxy; orthobothriotaxy A-β [2,28]. Legs: tarsus with very numerous fine median setae ventrally. Tibial spurs reduced on leg IV, vestigial on leg III.

Morphometric values (in mm) of the new species described. Total length, 10.81. Carapace: length, 1.60; anterior width, 0.87; posterior width, 1.47. Metasomal segment I: length, 0.93; width, 0.80. Metasomal segment V: length, 1.73; width, 0.67; depth, 0.65. Vesicle: width, 0.40; depth, 0.47. Pedipalp: femur length, 1.53, width, 0.40; patella length, 1.67, width, 0.47; chela length, 2.07, width, 0.33, depth, 0.40; movable finger length, 1.67.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Profs. John L. Cloudsley-Thompson, London, and J.-M. Betsch, ‘Muséum national d'histoire naturelle’, Paris, for reviewing the manuscript.