1 Introduction

Higher plants survive in a constantly fluctuating environment, which has driven the evolution of a highly flexible metabolism and growth (basic growth curve of slow–fast–slow) and development necessary for their sessile lifestyle [1–3]. In contrast to the situation in the natural world, the detailed dissection of the regulatory networks that govern higher plants' responses to abiotic insults and their biotic stress aspects have been studied almost exclusively in controlled environments where a single challenge has been applied [4–21]. Higher plant metabolism must be highly regulated in order to allow effective integration of a diverse spectrum of biosynthetic pathways that are reductive in nature [21–24], in which the regulation does not completely avoid photodynamic or reductive activation of molecular oxygen to produce ROS, particularly superoxide, H2O2 and singlet oxygen [15–17]. However, in many cases, the production of ROS is genetically programmed, induced during the course of development and by environmental fluctuations, and has complex downstream effects on both primary and secondary metabolism [24–34]. Higher plant cells produce ROS, particularly superoxide and H2O2, and as second messengers in many processes associated with plant growth and development [21–26,35]. Moreover, one of the major ways in which higher plants transmit information concerning changes in the changing environment is via the production of bursts of superoxide at the plasma membrane [27,28]. Situations that provoke enhanced ROS production have in the past been categorized under the heading of oxidative stress, which in itself is a negative term implying a harmful process, when in fact it is probably in many cases quite the opposite, enhanced oxidation being an essential component of the repertoire of signals that higher plants use to make appropriate adjustments of gene expression and cell structure in response to environmental and developmental cues [36–44]. Rather than involving simple signaling cassettes, emerging concepts suggest that the relationship between metabolism and redox state is complex and subtle [31,45–50] (Fig. 1). This article covers several important aspects of antioxidants and redox signaling in higher plants, including biological roles of main antioxidants, ROS and redox signaling, antioxidants and redox sensing mechanisms, and a network for redox signaling.

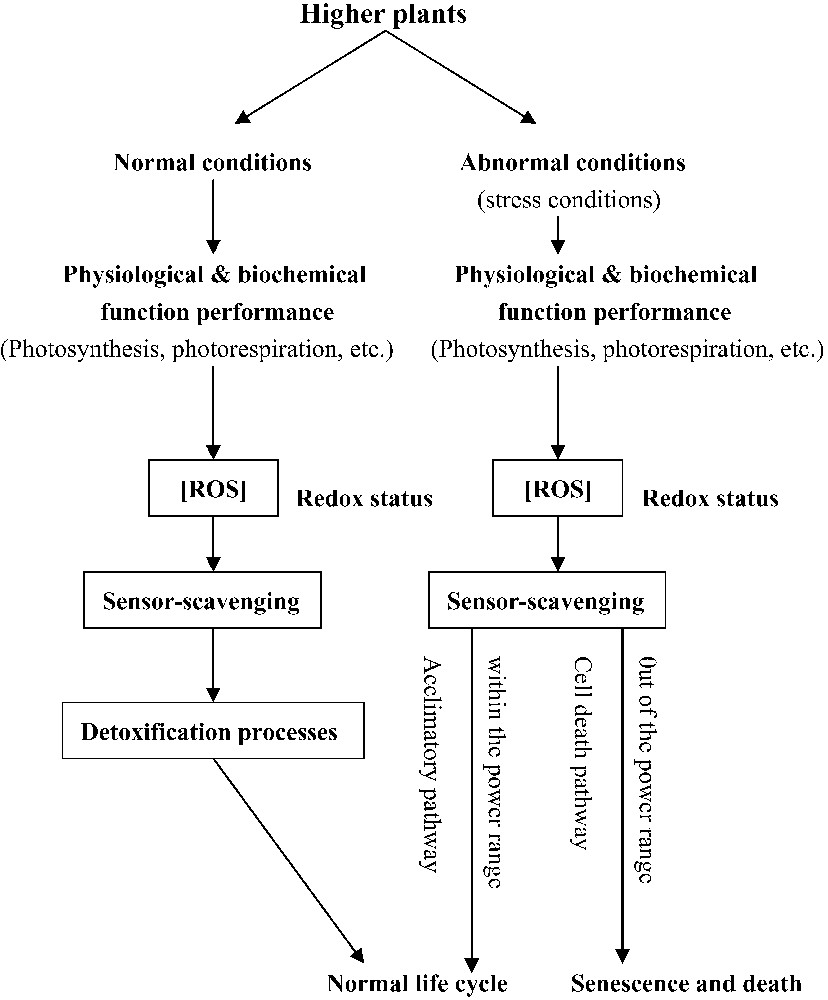

Related processes for main antioxidants and redox signaling in plants and vegetation; modified from [65].

2 Biological roles of main antioxidants in higher plants and vegetation

2.1 α-Tocopherol

α-Tocopherol, found in green parts of plants, scavenges lipid peroxy radicals through the concerted action of other antioxidants [31,45]. Further, tocopherols were also known to protect lipids and other membrane components by physically quenching and chemically reacting with O2 in chloroplasts, thus protecting the structure and function of PSII [32,46]. Researchers reported a two-fold increase in α-tocopherol in turf grass under water stress [33,47]. Ascorbate is one of the most extensively studied antioxidants and has been detected in the majority of plant cell types, organelles and apoplast [34,35]. Ascorbate is synthesized in the mitochondria and is transported to the other cell components through a proton-electrochemical gradient or through facilitated diffusion. Further, ascorbic acid also has been implicated in regulation of cell elongation [36,49].

In the ascorbate-glutathione cycle, two molecules of ascorbic acid are utilized by APX to reduce H2O2 to water with concomitant generation of monodehydro-ascorbate. Monodehydro-ascorbate is a radical with a short life time and can disproportionate into dehydroascorbate and ascorbic acid. The electron donor is usually NADPH and catalyzed by monodehydro-ascorbate reductase or ferredoxin in water–water cycle in the chloroplasts [37]. In plant cells, the most important reducing substrate for H2O2 removal is ascorbic acid [38,39,51–62]. A direct protective role for ascorbic acid has also been demonstrated in rice. The partial protection against damage from flooding conditions in rice was provided by the prior addition of ascorbic acid [40]. α-Tocopherols (vitamin E) are lipophilic antioxidants synthesized by all plants. α-Tocopherols interact with the polyunsaturated acyl groups of lipids, stabilize membranes, and scavenge and quench various reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid soluble by-products of oxidative stress [41,42].

Singlet oxygen quenching by tocopherols is highly efficient, and it is estimated that a single α-tocopherol molecule can neutralize up to 120 singlet oxygen molecules in vitro before being degraded [43]. Because of their chromanol ring structure, tocopherols are capable of donating a single electron to form the resonance-stabilized tocopheroxyl radical [44]. α-Tocopherols also function as recyclable chain reaction terminators of polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) radicals generated by lipid oxidation [45]. α-tocopherols scavenge lipid peroxy radicals and yield a tocopheroxyl radical that can be recycled back to the corresponding α-tocopherol by reacting with ascorbate or other antioxidants [46]. α-Tocopherols are major lipid soluble antioxidants present in the PUFA-enriched membranes of chloroplasts and are proposed to be an essential component of the plastid antioxidant network. The most attributed function of tocopherols is their involvement in various mechanisms in protecting PUFAs from oxidation [47]. ROS generated as by-products of photosynthesis and metabolism are potential sources of lipid peroxidation in plant cells. α-Tocopherol levels increase in photosynthetic plant tissues in response to a variety of abiotic stresses [48]. α-Tocopherols scavenge and quench various ROS and lipid oxidation products, stabilize membranes, and modulate signal transduction [48,49]. Synthesis of low-molecular-weight antioxidants, such as α-tocopherol, has been reported in drought-stressed plants [49]. Oxidative stress activates the expression of genes responsible for the synthesis of tocopherols in higher plants [49,50].

Antioxidants including α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid have been reported to increase following triazole treatment in tomato, and these may have a role in protecting membranes from oxidative damage, thus contributing to chilling tolerance [51]. Triazole increases the levels of antioxidants and antioxidant enzymes in wheat [52]. Photosynthetic apparatus and membrane could be affected by water stress. α-Tocopherol is a lipid-soluble antioxidant associated with the biological membrane of cells, especially the membrane of the photosynthetic apparatus [63]. Research has shown that water deficiency may result in an increase of tocopherol concentration in plant tissues [50,51]. Some evidence implied that tocopherol content of soybean leaves was increased as the amount of rainfall decreased [52]. This is consistent with the reports of [53], which showed that subjecting spinach to water deficit increased the content of α-tocopherol in the leaves. Based on the studies of 10 different grass species under water stress, the researcher found that drought stress led to an increase of 1- to 3-fold of tocopherol concentration in nine out of ten species [53,60]. They pointed out that the species with a high tolerance to stress are defended through tocopherol. Moreover, highly significant correlations were observed between stress tolerance and α-tocopherol concentration (the precursor of α-tocopherol; Spearmans rank correlation coefficient ).

2.2 Ascorbic acid

A continuous oxidative assault on plants during drought stress has led to the presence of an arsenal of enzymatic and non-enzymatic plant antioxidant defenses to counter the phenomenon of oxidative stress in plants [54]. Ascorbic acid (AA) is an important antioxidant, which reacts not only with H2O2, but also with O−2, OH and lipid hydroperoxidases [46,55]. AA is water soluble and also has an additional role in protecting or regenerating oxidized carotenoids or tocopherols [55,56]. Water stress resulted in a significant increase in antioxidant AA concentration in turf grass [57]. Ascorbic acid showed a reduction under drought stress in maize and wheat, suggesting its vital involvement in deciding the oxidative response [58]. Some studies reported a decrease in the level of antioxidants, including ascorbic acid, with an increase in stress intensity in wheat. Ascorbic acid can also directly scavenge 1O2, O−2 and ⋅OH and regenerate tocopherol from tocopheroxyl radicals, thus providing membrane protection [58,59]. Ascorbic acid also acts as a co-factor of violaxanthin de-epoxidase, thus sustaining dissipation of excess excitation energy [59,60]. Antioxidants such as ascorbic acid and glutathione are involved in the neutralization of secondary products of ROS reactions [45,61–64].

Ascorbate (vitamin C) occurs in all plant tissues, usually being higher in photosynthetic cells and meristems (and some fruits). About 30 to 40% of the total ascorbate is in the chloroplast and stromal concentrations as high as 50 mM have been reported [62]. It is highest in the mature leaf, where the chloroplasts are fully developed and the chlorophyll levels are highest. Although it has been determined that d-glucose is the precursor of l-ascorbic acid, the synthetic pathway has not been totally understood [61,63]. Ascorbic acid has effects on many physiological processes, including the regulation of growth, differentiation and metabolism of plants. A fundamental role of AA in the plant defense system is to protect metabolic processes against H2O2 and other toxic derivatives of oxygen. Acting essentially as a reductant and reacting with and scavenging many types of free radicals, AA reacts non-enzymatically with superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and singlet oxygen. It can react indirectly by regenerating α-tocopherol or in the synthesis of zeaxanthin in the xanthophyll cycle. Therefore, AA influences many enzyme activities, and minimizes the damage caused by oxidative process through synergic function with other antioxidants [60–65].

2.3 Reduced glutathione

Glutathione is a tripeptide (α-glutamyl cysteinylglycine), which has been detected virtually in all cell compartments such as cytosol, chloroplasts, endoplasmic reticulum, vacuoles, and mitochondria [66]. Glutathione is the major source of non-protein thiols in most plant cells. The chemical reactivity of the thiol group of glutathione makes it particularly suitable to serve a broad range of biochemical functions in all organisms. The nucleophilic nature of the thiol group is also important in the formation of mercaptide bonds with metals and for reacting with selected electrophiles. This reactivity along with the relative stability and high water solubility of GSH makes it an ideal biochemical to protect plants against stress including oxidative stress, heavy metals and certain exogenous and endogenous organic chemicals [67,68].

Glutathione takes part in the control of H2O2 levels [56,63]. The change in the ratio of its reduced (GSH) to oxidized (GSSG) form during the degradation of H2O2 is important in certain redox signaling pathways [64]. It has been suggested that the GSH/GSSG ratio, indicative of the cellular redox balance, may be involved in ROS perception [63,64]. Reduced glutathione (GSH) acts as an antioxidant and is involved directly in the reduction of most active oxygen radicals generated due to stress. There was a study reporting that glutathione, an antioxidant, helped to withstand oxidative stress in transgenic lines of tobacco [39,63].

2.4 Proline oxidase

The typical first response of all living organisms to water deficit is osmotic adjustment [69–74]. To counter with drought stress, many plants increase the osmotic potential of their cells by synthesizing and accumulating compatible osmolytes such as proline, and for this, the main regulating enzyme is proline oxidase (PROX) [58–60]. A sharp reduction in proline oxidation was observed under water stress in bean and Zea mays [61–63]. Proline oxidase converts proline to glutamate. Thus this enzyme also influences the level of free proline. The pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase is the rate-limiting enzyme in proline biosynthesis in plants and is subjected to feedback inhibition by proline. It has been suggested that the feedback regulation of P5CS is lost in plants under stress conditions [71–73].

2.5 γ-Glutamyl kinase

γ-Glutamyl kinase is an important regulating enzyme in the synthesis of proline. The induction of proline accumulation may be due to an activation of proline synthesis through glutamate pathway involving γ-glutamyl kinase glutamyl phosphate reductase and Δ-pyroline-5-carboxylate reductase activities [74–77]. Variation in γ-glutamyl kinase activities was reported in tomato in different physiological regions [75]. The first step of proline biosynthesis is catalyzed by γ-glutamyl kinase. γ-Glutamyl kinase belongs to a family of amino acid kinase, and a predicted three-dimensional model of this enzyme was constructed based on the crystal structures of three related kinases.

Plants have two proline biosynthetic pathways: the glutamate pathway and orinithine pathway, with the former appearing to play a predominant role under osmotic stress [35,46,77]. In the glutamate pathway, glutamate is converted by γ-glutamyl phosphate reductase into γ-glutamyl semialdehyde. This product cyclizes spontaneously to (P5C) -pyrroline-5-carboxylate, which is reduced by NADPH to proline by -pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase [76,77]. The γ-glutamyl kinase activity is higher in NaCl-stressed radish [73].

3 ROS and redox signaling driven by environmental stresses in higher plants

Higher plants, as other aerobic organisms, require oxygen for the efficient production of energy [40]. During the reduction of O2 to H2O, reactive oxygen species (ROS), namely superoxide radical (O⋅−2), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (OH⋅) can be formed [41,42]. Most cellular compartments in higher plants have the potential to become a source of ROS. Environmental stresses that limit CO2 fixation, such as drought and salt stress, ozone and high or low temperatures, reduce NADP+ regeneration by the Calvin cycle; consequently, the photosynthetic electron transport chain is over-reduced, producing superoxide radicals and singlet oxygen in the chloroplasts [43–45,56,59]. To prevent over-reduction of the electron transport chain under conditions that limit CO2 fixation, higher plants evolved the photorespiratory pathway to regenerate NADP+ [47,49]. As part of the photorespiratory pathway, H2O2 is produced in the peroxisomes, where it can also be formed during the catabolism of lipids as a by-product of β-oxidation of fatty acids [50,62].

Because of the highly cytotoxic and reactive nature of ROS, their accumulation must be under tight control. Higher plants possess very efficient enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense systems that allow scavenging of ROS and protection of plant cells from oxidative damage [51–53,60–62]. The distinct subcellular localization and biochemical properties of antioxidant enzymes, their differential inducibility at the enzyme and gene expression level and the plethora of non-enzymatic scavengers render the antioxidant systems a very versatile and flexible unit that can control ROS accumulation temporally and spatially [54,61–64]. The above controlled modulation of ROS levels is significant in the light of the recent evidence for a signaling capacity of ROS [55,60–64].

Higher plants can sense, transduce, and translate the ROS signals into appropriate cellular responses, the process of which requires the presence of redox-sensitive proteins that can undergo reversible oxidation/reduction and may switch ‘on’ and ‘off ’depending upon the cellular redox state [56,61]. ROS can oxidize the redox-sensitive proteins directly or indirectly via the ubiquitous redox-sensitive molecules, such as glutathione (GSH) or thioredoxins, which control the cellular redox state in higher plants [57,63,65,66]. Redox-sensitive metabolic enzymes may directly modulate the corresponding cellular metabolism, whereas redox-sensitive signaling proteins execute their function via downstream signaling components, such as kinases, phosphatases, and transcription factors [58,59,62]. Currently, two molecular mechanisms of redox-sensitive regulation of protein function prevail in living organisms [23–25,36,42,60–64]. Signaling mediated by ROS involves hetero-trimeric G-proteins [29] and protein phosphorylation regulated by specific MAP kinases and protein Tyr phosphatases [31,63]. The biochemical and structural basis of kinase pathway activation by ROS remains to be established in higher plants, but thiol oxidation possibly plays a key role [37,46,62]. The best-characterized redox signal transduction system in higher plants is the stromal ferredoxin–thioredoxin system, which functions in the regulation of photosynthetic carbon metabolism. Signal transmission involves disulfide-thiol conversion in target enzymes and is probably achieved by a light-induced decrease in the thioredoxin redox potential from about −0.26 V to about −0.36 V [27,36,61]. Thiol groups are likely important in other types of redox signal transduction, including ROS sensing by receptor kinases, such as ETR1 [48,60]. ROS in higher plants must utilize and/or interfere with other signaling pathways or molecules, forming a signaling network [61,64]. Increasing evidence shows that higher plant hormones are positioned downstream of the ROS signal. H2O2 induces accumulation of stress hormones, such as salicylic acid (SA) and ethylene [31,36]. Tobacco plants exposed to ozone accumulate ABA and induction of the PDF1.21 gene by paraquat is impaired in Arabidopsis mutants insensitive to jasmonates (JA) and ethylene [42,46]. Higher plant hormones are not only located downstream of the ROS signal, but ROS themselves are also secondary messengers in many hormone signaling pathways [16,19,64–66]. No doubt, feedback or feedforward interactions may conceivably occur between different hormones and ROS [23,28,39,57,70–78].

4 Concluding remarks

Higher plants have evolved an extensive range of defense systems to survive continuous assault by an arsenal of abiotic and biotic attacks, constantly changing weather and other environmental conditions. Unraveling the physiological and molecular basis for the plasticity of plant defending metabolism not only provides access to a largely untapped resource of genes and selection markers for breeding enhanced stress tolerance in crops, but also ensures improved food security and improving ecoenvironmental construction worldwide [6–8,10,49–69,78].

Living organisms can be viewed as reducing–oxidizing (redox) systems in which catabolic, largely oxidative processes produce energy and anabolic, principally reductive processes, assimilate it. Aerobic organisms exploit the redox potential of oxygen while controlling oxidation. A key feature determining the size of the plant ‘physiological window’ where metabolic functions can be maintained and regulated is the extent to which oxidative reactions can be tightly controlled. If environmental changes are too extreme to allow short-term metabolic controls to maintain fluxes through primary metabolism while preventing uncontrolled oxidation, then stress-induced damage ensues [49–52]. Here, there is an obvious stress threshold [57,59,63,67–69]. In this situation, acclamatory changes in gene expression are induced in attempt to restore redox homeostasis. If the repertoire of genomic responses is not insufficient or not appropriate, then primary metabolism is impaired, oxidative stress becomes increasingly important and cell death and senescence responses are triggered (Fig. 1). One of the earliest responses of plants to pathogens, wounding, drought, extremes of temperature or physical and chemical shocks is the accumulation of ROS such as superoxide, hydroxyl radicals, hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen, and others. The oxidative stress that ensues is a widespread phenomenon. It is extensively observed in wheat and other plants exposed to most, if not all, biotic and environmental stresses. ROS are key components contributing to cellular redox status. They participate in all processes controlled by redox reactions. These include signal transduction, gene expression, protein synthesis and turnover, thiol-disulphide exchange reactions and regulation of metabolism [6,56,57,59]. ROS accumulation is sensed as an ‘alarm’ signal that initiates pre-emptive defense responses. Common and linked signal transduction pathways are activated that can lead either to stress acclimation or to cell death, depending on the degree of oxidative stress experienced. Wheat responses to stresses are therefore directed to acclimate and repair damage, which is the basic common feature of organisms [67–69].

Besides exacerbating cellular damage, ROS can act as ubiquitous signal molecules in higher plants. ROS are a central component in stress responses and the level of ROS determines the type of response. Antioxidants and ROS are an important interacting system with different functions in higher plants, which ensures themselves a highly flexible organism [35,39,58]. Redox signal transduction is a universal characteristic of aerobic life honed through evolution under natural and selecting pressure to balance information from metabolism and the changing environment [62–78]. Higher plant cells can be considered a series of interconnecting compartments with different antioxidant buffering capacities determined by differences in synthesis, transport and/or degradation. There is a set of discrete locations where signaling is controlled (or buffered) independently in higher plant cells, which permits redox-sensitive signal transduction to occur in locations such as the apoplast, the thylakoid, and, perhaps, the endoplasmic reticulum, whereas other highly buffered spaces have a much higher threshold for ROS signals. Both oxidants and antioxidants fulfill signaling roles to provide information on higher plant health, particularly in terms of robustness for defense, using kinase-dependent and independent pathways that are initiated by redox-sensitive receptors modulated by thiol status. Antioxidants are not passive bystanders in this crosstalk, but rather function as key signaling components that constitute a dynamic metabolic interface between higher plant cell stress perception and physiological responses. Increasing current data suggest that glutathione is a key arbiter of the intracellular redox potential, and ascorbate is particularly influential in setting threshold for apoplastic and cytoplasmic signaling [57,60–78]. Differential antioxidant concentrations between compartments make antioxidant-driven vectorial signaling through processes such as ascorbate-driven electron transport or futile cycles. There can be no doubt that transgenic plants will be invaluable in assessing the precise role that main antioxidants and ROS play in the functional network that controls stress tolerance. Although steps in the biosynthetic pathways resulting in antioxidant accumulation in higher plants have been primarily characterized at the physiological and molecular level, the full cast of participants involved in the complex regulation of their accumulation remains to be identified. This will require not only a better understanding of the degradation and transport of antioxidants in higher plants, but also elucidation of the molecular events responsible for stress perception and stress-related signal transduction via a wider scope of tested plants. Basic research leading to the characterization of tightly regulated stress-inducible promoters that are also responsive to appropriate tissue-specific regulation and endogenous developmental programs is likely to be critical in improving the overall field performance of transgenic crops. The future will determine more precisely how ascorbate, glutathione, and tocopherol are involved in initiating and controlling redox signal transduction and how they trigger the gene expression of other related responses to optimize survival strategies. In addition, other problems are how antioxidants coordinate growth and development of higher plants in a constantly changing environment, how redox signaling is linked with hormonal regulation, nutrient status and redox potential of higher plants, and how their redox signaling is cooperated with inter- and intracellular signaling, transport capacity, developmental and environmental cues to maintain an appropriate dynamic homeostasis for stress tolerance and efficient survival. In combination with the recent literature, the production and regulation of related antioxidants and oxidants in plants were illustrated in Fig. 1.

Acknowledgements

Research in our laboratory is supported jointly by the 973 Program of China (2007CB106803), the Shao Ming-An's Innovation Team Group Projects of the Education Ministry of China and Northwest A&F University, and the International Cooperative Partner Plan of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The author apologizes for not citing more authors of the original publications because of space limitation. Special thanks are given to two referees for their instructive comments and suggestions.