1 Introduction

Leaves are determinate organs that are the main photosynthetic structures of land plants. As such, they must optimise their light-capturing surface and their gas exchanges with the environment, which would ideally require a leaf as large and thin as possible. However, leaves are also subjected to the physical laws that constrain increases in size and decreases in thickness. Thin leaves are more subject to water loss and heat up more rapidly when exposed to light. Large leaves require more support tissues, which results in a higher biomass investment per unit leaf area [1]. Broad leaves also heat rapidly, especially when the ambient airflow is low [2]. Increasing the level of leaf dissection, via the formation of lobes, helps to cool down the leaf [2], but also has opposite effects on the surface area available for light capture. On the one hand, it reduces the surface area of each individual leaf, whereas on the other hand, it may increase light interception at the whole plant level by reducing the self-shading of lower leaves by upper leaves [3]. Therefore, the effects of leaf shape and size on plant fitness is a complex issue. For instance, comparison of near-isogenic cotton lines with contrasted leaf shapes showed that leaves with intermediate lobing were the most efficient at the plant level [4]. Such complex, and sometimes opposite constraints may explain the incredible diversity in shapes and sizes that is observed for leaves in different species or even within a single individual, depending on environmental factors or developmental stage (leaf heteroblasty).

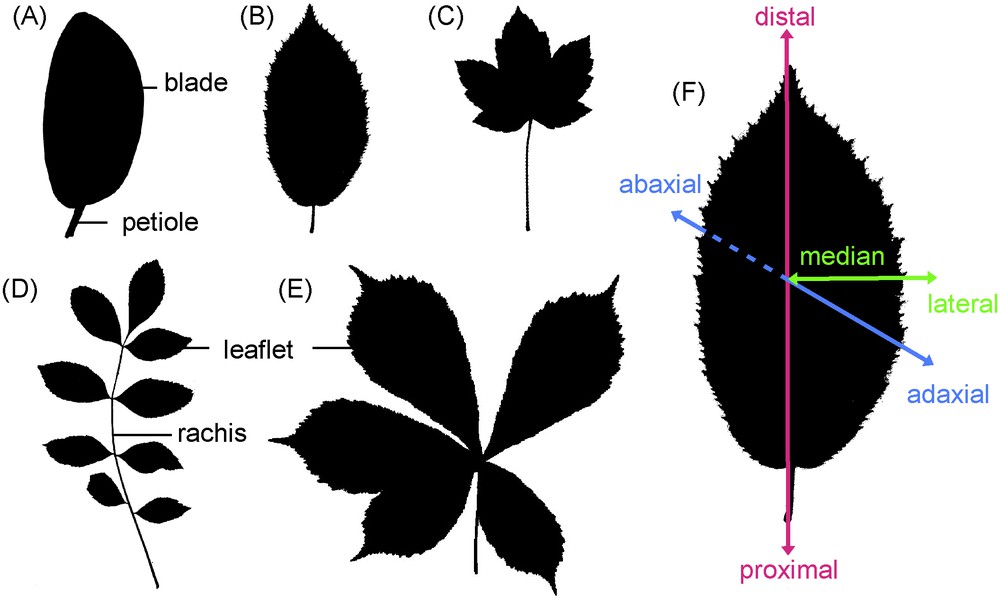

In the wide diversity of leaf shapes, two main groups can be distinguished according to the degree of complexity: simple leaves and compound leaves (Fig. 1), [5]. Here, we will present genetic, molecular and hormonal networks acting during leaf initiation, outgrowth and shaping, and present some ideas about how these networks could have been modified to generate contrasting leaf shapes. This review will concentrate on the dicot leaf, either on simple leaves (like the plant model Arabidopsis thaliana) or on compound leaves (such as tomato and pea).

Overview of the different leaf architectures. Two main leaf architectures are recognized: simple leaves formed by a single blade supported by the petiole (A–C), and compound leaves with several units called leaflets (D, E). Compound leaves are further divided into pinnate leaves when the leaflets are attached on different parts of an elongated axis called the rachis (D), and into palmate leaves when all leaflets unit on a single point (E). The leaf or leaflet margin is either entire (A), serrated (B, D, E) or lobed (C). Leaves are organised along three axes: proximodistal (petiole to blade tip), adaxial-abaxial (or dorsoventral from the upper to the lower side) and mediolateral (midrib to margin). Shadows of common European trees leaves are shown: magnolia (A), hornbeam (B, F), maple (C), ash (D) and chestnut tree (E).

2 Leaf initiation at the meristem, or the first step towards determinacy

2.1 The SAM is the ultimate source of all aerial organs

The shoot apical meristem (SAM) contains a pool of stem cells and initiates all the leaves or flowers. The earliest event associated with organ initiation is the switch from an indeterminate to a determinate fate in the founder cells, a small group of cells that will give rise to the lateral organs. The mechanisms controlling meristem function or the process of primordium initiation will not be detailed here, as recent reviews are available, including in this issue [6–12], but we will highlight some of the specific points that are essential to understand later steps of leaf development.

2.2 Leaving the meristem behind: the switch from indeterminate to determinate fate during primordium initiation

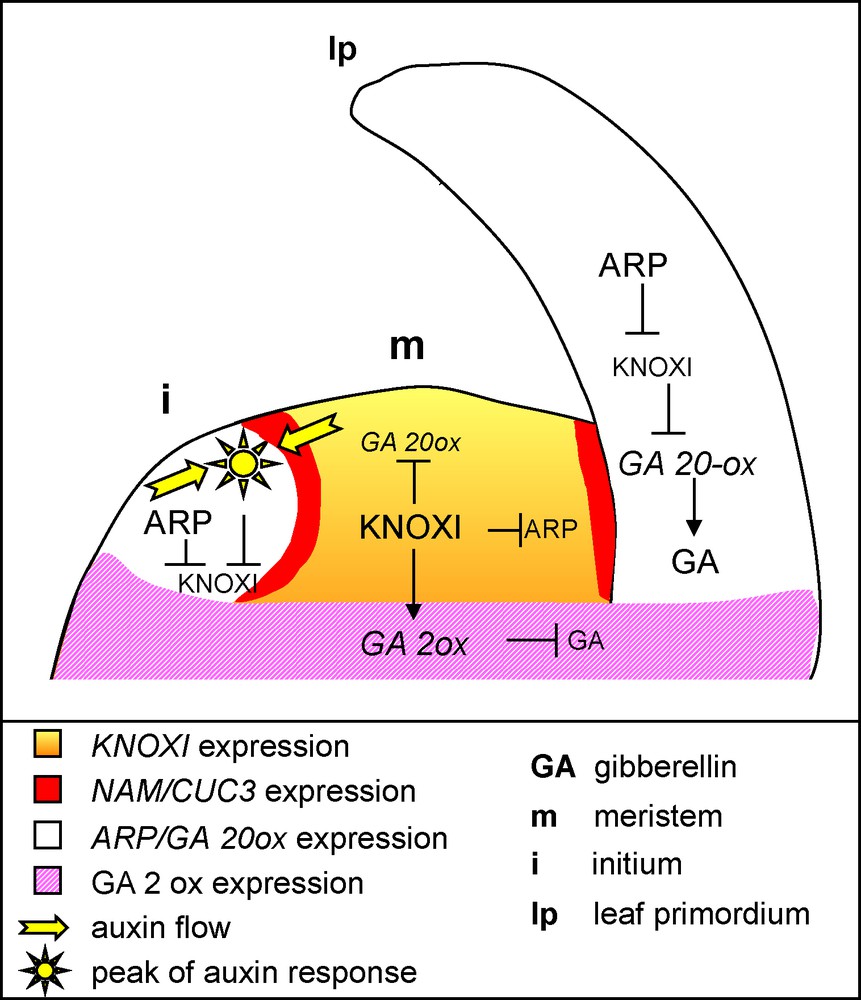

The SAM is characterized by the expression of Class I KNOTTED1-LIKE HOMEOBOX (KNOXI) genes represented in Arabidopsis by the SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM), BREVIPEDICELLUS/KNOTTED-LIKE FROM Arabidopsis1 (BP/KNAT1), KNAT2 and KNAT6 genes [13–17]. These homeodomain transcription factors are required for the establishment and maintenance of the meristems, in part via the activation of the cytokinin pathway [13,18]. They show distinct expression patterns in the SAM but share a common zone of repression at the site of the incipient leaf primordium (Fig. 2) [13,19]. This repression marks the transition to a determinate fate and is essential for proper leaf development, as ectopic KNOXI expression during simple leaf development leads to severe defects, including leaf lobing and formation of ectopic meristems [20–22].

Genetic and molecular network controlling leaf initiation and differentiation.KNOXI genes are expressed in the SAM, where they repress the ARP genes and the GA pathway to maintain cells in an undifferentiated state. Local auxin accumulation sets up the site of primordium initiation, and together with the ARP genes, represses KNOXI expression. Repression of the KNOXI genes in the primordium allows the GA pathway to be derepressed, thus leading to growth and differentiation. KNOXI contribute to the expression of the GA 2-oxidase that inactivates GA.

Given the importance of proper regulation of KNOXI genes, it is not surprising that several pathways contribute to their repression in the leaf. One of these pathways involves auxin. Local auxin accumulation, resulting from PIN1-mediated polar transport of this hormone, determines the site of primordium initiation [6,8,12,23]. Real-time imaging of developing apices and genetic analysis showed that these peaks of auxin also contribute to KNOXI repression (Fig. 2) [24,25]. Another pathway repressing KNOXI genes involves the ARP genes coding for MYB-domain transcription factors, and named after Arabidopsis ASYMETRIC LEAVES1 (AS1), maize ROUGH SHEATH2 (RS2) and Antirrhinum majus PHANTASTICA (PHAN) genes [26–29]. ARP genes are specifically expressed in lateral organ founder cells where they repress KNOXI expression. In turn, AS1 expression is excluded from the meristem by STM, leading to a complementary expression pattern of KNOXI and ARP genes (Fig. 2) [26]. The mechanism of AS1-mediated KNOXI repression was recently elucidated [30]. AS1 forms a repressor complex, together with the LOB domain protein AS2, the predicted RNA binding protein RIK and the chromatin-remodeling protein HIRA. This complex binds to the promoter of the BP and KNAT2 genes during early stages of primordium development and represses the expression of these two KNOXI genes. Such a repression was proposed to occur via chromatin modifications that lead to a silenced state that is stably transmitted through cell divisions during later stages of leaf development [30].

Besides morphological modifications, ectopic KNOXI expression in leaves also leads to a cellular phenotype characterized by reduced cell expansion and differentiation [10]. Such a phenotype suggests a defect in the gibberellin (GA) pathway, a hypothesis supported by the observation that normal leaf development is restored in KNOXI overexpressors by the activation of the GA pathway [31]. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that a large part of KNOXI protein function is mediated by its inhibitory effects on GA synthesis and signalling [8,32]. First, KNOXI transcription factors of different species directly downregulate the expression of the GA 20-OXIDASE gene that codes for an enzyme controlling a key step of GA biosynthesis (Fig. 2) [31,33,34]. Furthermore, STM promotes the expression of the GA 2-OXIDASE gene involved in the inactivation of GA, which protects the meristem from GAs that may diffuse from the primordium [35]. Thus, the combined effects of KNOXI inhibition of GA synthesis and promotion of GA inactivation lead to reduced GA signalling. Such KNOXI-mediated repression of GA signalling is required for maintaining the meristem in an undifferentiated state, but when this pathway is ectopically activated in the leaf, it delays cell expansion and differentiation and leads to abnormal leaf development.

2.3 Defining the organ boundaries

Proper lateral organ development also requires the physical separation of individual organ primordia, which is accomplished through the action of the three Arabidopsis CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1, 2 and 3 (CUC1, 2 and 3) genes. These genes encode NO APICAL MERISTEM/ATAF/CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (NAC) plant-specific transcription factors and are specifically expressed in a narrow file of cells at the base of organs that marks their boundary with neighbouring organs or with the meristem (Fig. 2) [36–38]. This specific expression pattern may be a response to the local peaks of auxin associated with primordium formation [25]. Inactivation of one or several of the CUC genes leads to various levels of organ fusion [36–38]. CUC1 and CUC2, are post-transcriptionally regulated by a microRNA, miR164, like all other members of the NAM clade, named after the petunia NO APICAL MERISTEM (NAM) gene [39]. In contrast, CUC3 is not targeted by miR164. miRNAs are part of a diverse family of small regulatory non-coding RNAs and have emerging roles in the regulation of plant development [40,41]. Indeed, miR164-mediated regulation of CUC1/CUC2 is important for the homeostasis of the boundary domain [42–46].

3 Building the basic leaf shape: how and why are the polarization axes setup?

3.1 A functional polarisation of the leaf

Emerging from the SAM, the leaf primordium is a radial structure that will rapidly organize itself along three axes: proximodistal, mediolateral and adaxial-abaxial (or dorsoventral) (Figs. 1 and 3A). Here, we will only discuss the mechanism of leaf polarization along the adaxial-abaxial axis, as it is the best understood from a molecular and genetic perspective, and is the most relevant for the physiology of the leaf. Early polarization along the adaxial-abaxial axis during primordium development serves to specify cell types within the mature leaf. The adaxial side of the leaf blade is exposed to the sun and differentiates into palisade cells that are optimised for space filling and have a high chloroplast content, thus maximizing light interception. The opposite abaxial side is constituted of spongy parenchymatous cells leaving intercellular spaces that promote gas exchanges. Stomata distribution is also often polarized, with a higher density on the abaxial side. Finally, vascular tissues are also polarized along this axis, as the xylem is only found in the adaxial side and the phloem in the abaxial side.

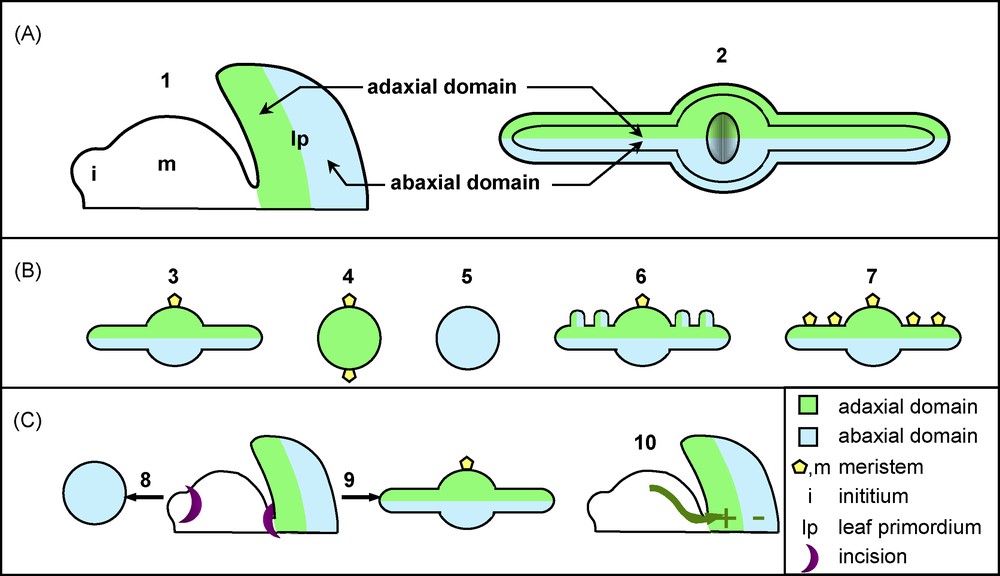

Adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity and leaf architecture. A. Adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity and meristem. (1) Scheme showing the orientation of the adaxial and abaxial domains of a young primordium relative to the shoot apical meristem; and (2) a transversal section of an expanded leaf B. Adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity, blade expansion and meristem formation. (3) A mature leaf shows an expanded blade formed by adaxial and abaxial domains and supports a secondary meristem in its axillary adaxial region; (4) Adaxialized mutants such as phb-1D form leaves with no blade expansion that carry ectopic meristems on their lower base; (5) Abaxialized mutants such as kan mutants develop bladeless leaves that lack meristems; (6) The Antirrhinum phan mutant with patches of abaxial tissues on its adaxial side and ectopic outgrowths; (7) Ectopic meristems form on the adaxial side of the blade of plants overexpressing KNOXI genes. C. Adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity and signalling from the meristem. (8) An incision made between the meristem and a young primordium leads to the formation on a radial abaxialized organ. (9) If the incision is made latter, once the primordium is already polarized, a leaf with a normal organisation develops (10). These experiments provide evidence for a meristem-derived signal that promotes adaxial fate and/or represses abaxial fate.

The genetic control of adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity involves a multilayered regulatory network entailing a complex interplay between several classes of transcription factors and other regulators subjected to different levels of regulation. Furthermore, establishing this polarity is not an autonomous process occurring only in the leaf primordium but also involves communication with the meristem.

3.2 The antagonism between adaxial and abaxial factors controls leaf polarization

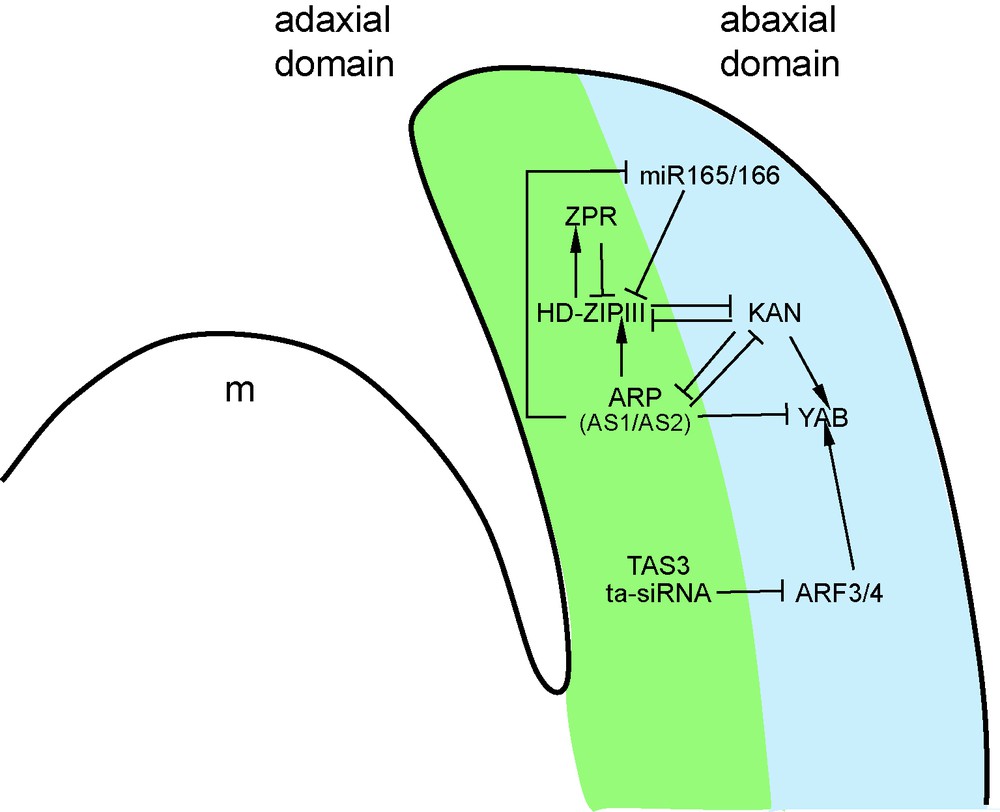

The core regulatory module controlling adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity is based on the antagonistic relationship between two sets of transcription factors that determine the identity of the adaxial and abaxial leaf domains. The class III HOMEODOMAIN-LEUCINE ZIPPER (HD-ZIPIII) genes REVOLUTA (REV), PHABULOSA (PHB) and PHAVOLUTA (PHV) of Arabidopsis are expressed on the adaxial side of the primordium [47], whereas members of the KANADI (KAN) and YABBY (YAB) gene families are expressed on the abaxial side (Fig. 4) [48,49]. These genes determine the identity of the leaf domain in which they are expressed, and repress the expression of the identity genes of the complementary domain (Fig. 4). For instance, leaves of kan loss-of-function mutants show an adaxialized phenotype (Fig. 3B) and an expansion of the expression of the HD-ZIPIII genes, whereas on the contrary, KAN over-expression leads to leaf abaxialization and HD-ZIPIII repression [50]. In addition to this antagonism between adaxial and abaxial factors, YAB expression is strongly reduced by the inactivation of the KAN genes, suggesting that the YAB genes act downstream of the KAN (Fig. 4) [50].

Genetic and molecular network controlling adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity. Two main genes families are involved in the definition of the identity of the adaxial and abaxial leaf domains: the KAN and HD-ZIPIII genes are, respectively, expressed in the abaxial and the adaxial domains, and thus define the identity of each territory. The antagonism between these two groups is at the root of their complementary expression domains in the leaf. The contribution of several other molecular actors reinforces these expression patterns: miR165/166 negatively regulates HD-ZIPIII genes, while ARP proteins promote HD-ZIPIII expression. In parallel, ARP proteins negatively control KAN and miR165/166 expressions. KAN factors activate the expression of the YAB genes that contribute to define the abaxial identity, while YAB genes are subjected to negative regulation by the ARP and TAS3 pathways.

3.3 Several partially redundant pathways contribute to reinforce polarization along the adaxial-abaxial axis

Interacting with this core-regulatory module, several other factors control leaf polarity. Most of these factors appear to modify the activity of the HD-ZIPIII, KAN and YAB components. Examples of such factors include the LITTLE ZIPPER (ZPR) proteins [51,52]. The ZPR proteins form heterodimers with HD-ZIPIII and prevent their binding to DNA. Interestingly, ZPR expression is induced by HD-ZIPIII, thus establishing a negative feedback loop (Fig. 4). This modulation of the activity of the HD-ZIPIII proteins appears, however, to have only a small contribution to leaf polarity, in contrast to the pathways described below.

Whereas the phan mutant revealed a central contribution of this gene to Antirrhinum adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity (Fig. 3B), the initially identified Arabidopsis as1 and as2 mutants showed no obvious polarity defect. However, identification of novel as1/as2 alleles in a different genetic background [53], and further genetic studies revealed the contribution of the AS1/AS2 pathway for the promotion of adaxial leaf fate [54–57]. AS1, together with AS2, positively regulate HD-ZIPIII expression, while they negatively regulate KAN and YAB expression (Fig. 4) [54–57]. If the AS1/AS2 pathway regulates components of the core regulatory module, the inverse also occurs: KAN1 directly represses AS2 expression in the abaxial domain of the leaf (Fig. 4) [58]. This reveals another mutually repressive loop between the adaxial AS1/AS2 factors and the abaxial KAN determinants, which contributes to the proper separation of the adaxial and abaxial domains. Finally, mutations in several ribosomal proteins or in components of the proteasome enhance the leaf polarity defects of as1 or as2 mutants [59–61]. However, the mechanism by which the regulation of protein translation and turnover feeds into the control of leaf polarity remains unknown.

Members of two classes of small RNAs are also involved in leaf polarity control. The related miR165/miR166 miRNAs have a prominent role in abaxial leaf fate. These miRNAs target the HD-ZIPIII PHB, REV and PHV transcripts (Fig. 4). All gain-of-function mutants of these genes identified thus far are mutated in the miR165/166 binding site [62,63], suggesting that miRNA-dependent regulation of these genes is critical for normal plant development. However, as these mutations also disrupt a StAR-related lipid transfer (START) domain, known to interact with lipids in animal systems, it was not clear whether the phenotype associated with these mutations was a consequence of a defective miR165/miR166 regulation, a modification of the properties of the START domain or a combination of both. The last two hypotheses were excluded by the observation that the expression of miR165/166-insensitive versions of HD-ZIPIII genes that possess silent mutations in the miRNA binding site (and therefore code for unmodified proteins) could phenocopy the original gain-of-function alleles [62,64]. The miR165/166 was reported to be expressed in the abaxial domain [65] or throughout the leaf primordium [56] and contributes to restrict HD-ZIPIII expression to the adaxial domain [65]. Interestingly, some evidence suggests that the AS1/AS2 pathway may increase HD-ZIPIII activity by reducing miR165/166 expression, consistent with the repressing activity of the AS1/AS2 complex [56].

The second class of small RNAs provides a link between leaf polarity and auxin. Auxin response is mediated by the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS (ARF), a class of transcription factors that binds to auxin-responsive promoter elements (ARE) in target genes regulated by auxin [66]. Two of these ARFs genes, ARF3/ETTIN and ARF4, were identified following a screen for suppressors of KAN overexpressors, thus providing the first genetic evidence for the involvement of auxin in adaxial-abaxial polarity. The expression of these two genes overlaps in the abaxial domain (Fig. 4), and their simultaneous inactivation leads to organ adaxialization [67]. Further genetic studies revealed, however, that the ARF3/ARF4 are not just merely downstream of the KAN pathway, but are more likely to cooperate with KAN for the promotion of abaxial fate. ARF3 and ARF4 are regulated by trans-acting small interfering RNAs (ta-siRNAs) produced from the TAS3 gene [54,68–70]. Although mutating components involved in ta-siRNA biogenesis or expressing a TAS3-insensitive ARF3 gene has an effect on leaf heteroblasty, no obvious effects on leaf polarity were observed [69,70]. However, such defects are observed when mutations of the ta-siRNA biogenesis machinery are combined with as1 mutations [40]. At the molecular level, the AS1 and TAS3 pathways redundantly repress the expression of YAB genes. This indicates a functional redundancy between the TAS3 and AS1 factors in the promotion of adaxial identity and the repression of abaxial fate.

3.4 Setting up polarity by mobile signals

Whereas the complex regulatory network described above accounts for the maintenance of the two complementary leaf domains, it cannot explain the establishment of polarity nor the alignment of leaf polarity with respect to the axis of the plant. Early expression studies suggested that the leaf initium is not polarized, as mRNA of both adaxial and abaxial determinants were detected throughout the initium [47,71]. However, recent advancements in real-time imaging of developing lateral organs indicate that polarization is concomitant with the formation of the initium [25]. Production of a diffusible signal is a mechanism widely used in animal systems to polarize organs or tissues, and recent evidence suggests that movement of ta-siRNA could play a similar role during leaf polarization. Due to a localized expression of the TAS3 gene and/or components of the ta-siRNA production machinery, TAS3 ta-siRNA are produced only in the outermost cells layers of the adaxial domain of the primordium [72–74]. The TAS3 ta-siRNAs diffuse across a limited number of cells, generating a gradient over the adaxial-abaxial axis. Computer simulations indicate that this gradient may sharpen the expression pattern of the ARF3/4 genes [75]. Interestingly, in maize the distribution of one component of the ta-siRNA production machinery remains polar in a radialized leaf of a mutant in which the expression of other genes becomes apolar [76]. This suggests that, at least in the maize leaf, ta-siRNA gradients have a prominent role in ad/abxial polarization.

Leaf polarization is always coordinated with respect to the meristem. Indeed, forward-looking microsurgical experiments made more than 50 years ago showed the existence of a signal emanating from the meristem and polarising the leaf. Incisions separating incipient primordia from the SAM result in radially abaxialized structures, when later incisions did not modify an already polarized organ (Fig. 3C) [77], suggesting that the signal is needed only to establish the polarity and not for its maintenance. Recent re-examination of these experiments further showed that an intact epidermal layer is required for meristem-primodium signalling [78]. What is the signal? Currently, this question is still open, but a candidate has arisen. It was proposed that a sterol/lipid molecule produced by the meristem could form a gradient and interact with the HD-ZIPIII and modify its activity [47]. Since the adaxial and abaxial domains would be exposed to different concentrations of the signal, a polarity could be initiated. No further observations however support this hypothesis, and the signal has not yet been identified.

3.5 Abaxial/adaxial polarization is important for all aspects of leaf function

Besides determining proper cell types, adaxial-abaxial polarization is also important for two other aspects of leaf development. First, proper definition of the two adaxial and abaxial domains is important for leaf flattening and blade outgrowth. Adaxialized or abaxialized mutants form finger-like leaves with no blade expansion (Fig. 3B) [50,79]. Furthermore, in some leaves of the Antirrhinum phan mutant, patches of abaxial tissues appear on the adaxial side of the leaf, and ridges resembling blades initiate from the boundary between these regions with different identities (Fig. 3B) [29]. These observations led to the hypothesis that signalling across the juxtaposed abaxial and adaxial domains is necessary to promote blade outgrowth [29]. The molecular mechanisms that mediate this signalling and promote blade outgrowth are currently unknown. However, genetic analysis points to a role of the YAB genes in the promotion of blade outgrowth [50]. Alternatively, a recent study underscored the role of elongated, specialized cells located at the margin of the leaf blade (the margin cells) and the possible role of brassinolides in the control of leaf growth and shaping [80]. Whether this is relevant for early blade outgrowth or limited to later stages of leaf shaping remains an open question.

The second implication of the adaxial-abaxial polarization is the formation of axillary meristems. These structures are normally located in the axil, i.e. on the adaxial side of the junction of the leaf petiole with the stem, and ectopic meristems that form on the leaf blade of KNOXI overexpressors, for instance, are also always located on the adaxial side (Fig. 3B) [22]. Furthermore, meristem formation is perturbed in leaf polarity mutants. Adaxialized leaves develop axillary meristems from the lower part of the leaf base [79], whereas abaxialized mutants are defective for meristem formation (Fig. 3B) [62]. Altogether, this demonstrates a link between the adaxial identity and the ability to develop meristems. The nature of this link is not yet understood, but some determinants of the adaxial domain such as PHB are also expressed in the meristem, suggesting that they could provide a molecular link between meristem function and adaxial leaf fate [47,81].

3.6 The same players but different roles? Conservation and specificities of the adaxial-abaxial regulatory network in different species

Except for some species (such as most cacti) in which the leaves are transformed into spines [82], flattening and polarization along the adaxial-abaxial axis is a general feature of most leaves. Although the knowledge of the regulatory networks at work in this process is by far best understood in Arabidopsis, more and more data become available for other species, such as the dicot Antirrhinum or the monocots maize and rice. The general picture that emerges from this overview is that most of the proteins or RNA regulators described above show a high level of conservation within vascular plants [83]; for instance, the maize RS2 ARP gene fully complements the Arabidopsis as1 mutant [84]. Although the function may be conserved, the importance of each pathway can be significantly different between species. An example of this is the different importance of the ARP pathway in Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum leaf polarity, as mentioned above. Another example is the different contributions of the TAS3 pathway, as witnessed by the difference in the severity of the leaf polarity defects observed in Arabidopsis and maize following the inactivation of the SGS3 gene that codes for a component of the ta-siRNA production machinery [54,68,73]. Therefore, the regulatory network may show significant differences between species, perhaps resulting from different developmental or environmental constraints.

4 Shaping the mature leaf: patterning and growth control

Once the three axes of polarization are set up, further patterning will occur in the leaf primordium to shape the vascular network and the leaf margin. Positional information provided by epidermal foci of auxin accumulation and routes of auxin flow from the margin to the centre of the primordium pattern the vasculature in the developing leaf [85]. In parallel, the epidermal auxin maxima determine the position of the marginal outgrowths that form the serrations [24]. A factor possibly downstream of auxin that mediates leaf margin dissection is the CUC2 gene. This gene is expressed in the sinus of the developing serrations and its activity, controlled by the miRNA miR164, determines the level of leaf dissection [86]. This dissecting role is conserved for CUC2 orthologues in several Eudicots [87,88]. All together, this indicates that the auxin/CUC/miR164 regulatory module acting during primordium initiation is also used during leaf margin sculpting.

In the subsequent phases of development, the leaf primordium gains in size and reaches its mature shape. Initially, cells present a high proliferation activity throughout the blade. Then, a proliferation arrest front progresses in a basipetal way, from the tip of the leaf to its base. After proliferation arrest, growth is achieved via cell expansion [89]. Whereas the basic components of the cell machinery have been identified and largely characterized, how their function is integrated during leaf development to generate a flat structure with a given shape and size remains unclear. Many mutants developing abnormal leaf shapes have been characterized over the years, and the defects of certain of these mutants have been traced back to variations in cell proliferation or expansion patterns [90–92]. A useful example of this is the Antirrhinum CINCINNATA (CIN) gene, which encodes a TEOSINTE BRANCHED/CYCLOIDEA/PROLIFERATING CELL FACTOR (TCP) transcription factor and which controls cell proliferation arrest. In cin mutants, leaves are crinkly, as a result of excess growth at their margins [93]. In Arabidopsis, a similar phenotype is found in the jaw-D dominant mutant, where the MIRJAW (MIR319) gene that targets several CIN-related TCPs is over-expressed [94].

5 Making compound leaves in a complex way

5.1 Delaying differentiation to elaborate compound leaves

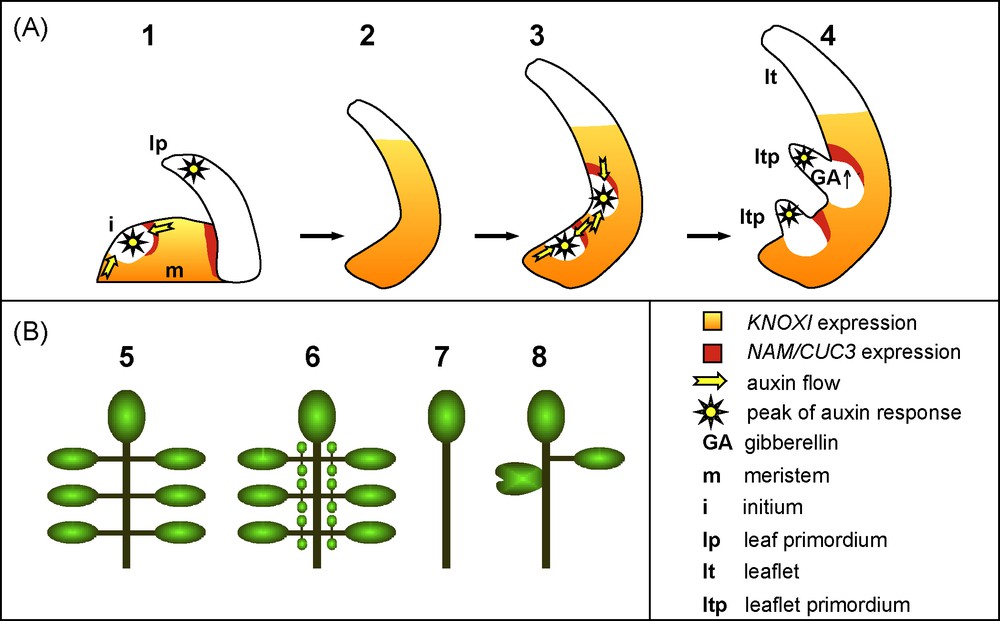

Whereas KNOXI genes are repressed during the entire process of simple leaf development, these genes are activated again during the development of most compound leaves following a transient phase of repression (Figs. 5 and 6) [95,96]. Recent work on an emerging model for compound leaf development, the Arabidopsis relative Cardamine hirsuta, showed that KNOXI activity is necessary for compound leaf formation (Fig. 5B) [97]. Reciprocally, a higher or prolonged KNOXI activity increases the complexity of compound leaves. For instance, ectopic expression of KNOXI transgenes leads to higher-order leaflets in cardamine and tomato (Fig. 5B) [96,97]. However, the activity of the KNOXI proteins is also modified indirectly by alteration in their protein interaction network. KNOXI proteins rely for their nuclear localization and DNA binding on the formation of heterodimers with another class of homeoproteins, the BEL proteins [11]. Furthermore, the BEL proteins interact with a newly identified truncated KNOXI protein called PTS/TDK1 [98]. Increasing the expression of the PTS/TDK1 gene or inactivating a specific BEL member leads to tomato leaves of higher complexity [98]. Interestingly, an increased expression of the PTS/TDK1 gene, due to a single nucleotide deletion in its promoter, is the basis for the increased leaf complexity of a wild tomato species collected by Charles Darwin from the Galapagos Islands [98]. All together, these observations indicate that KNOXI activity acts like a rheostat to control compound leaf complexity. How is this achieved? Based on its known role in the meristem, reactivation of KNOXI gene expression during compound leaf development may delay cell differentiation, and, thus, create a pseudomeristematic environment that is required for the elaboration of complex leaf structures. As in the meristem, KNOXI maintains an undifferentiated state by repressing the GA pathway in compound leaf primordia. Exogenous application of GA, or increased GA signalling due to the inactivation of the DELLA-type gene PROCERA, simplifies tomato leaf architecture and partly antagonizes the effects of KNOXI overexpression [31,99]. All together, this reveals the recruitment of the meristematic KNOXI/GA regulatory module to the developing primordium of compound leaves (Figs. 5 and 6).

Compound leaf development. A. Compound leaf development. (1–4) The initial developmental steps of a compound leaf are similar to those of a simple leaf: KNOXI genes are repressed in the initium and then, are turned-on again to maintain an undifferentiated state. Leaflet primordia are initiated in a process resembling the initiation of a leaf primordium. B. Compound leaf architecture modification. (5) Scheme of a normal compound leaf bearing several primary leaflets. (6) KNOXI genes overexpression leads to the formation of ectopic, higher order leaflets. (7) On the contrary, inactivation of KNOXI genes transforms the compound leaf into a simple structure. (8) Perturbation of auxin transport/response or reduced activity of the NAM/CUC3 boundary genes leads to fewer leaflets that can be partially fused.

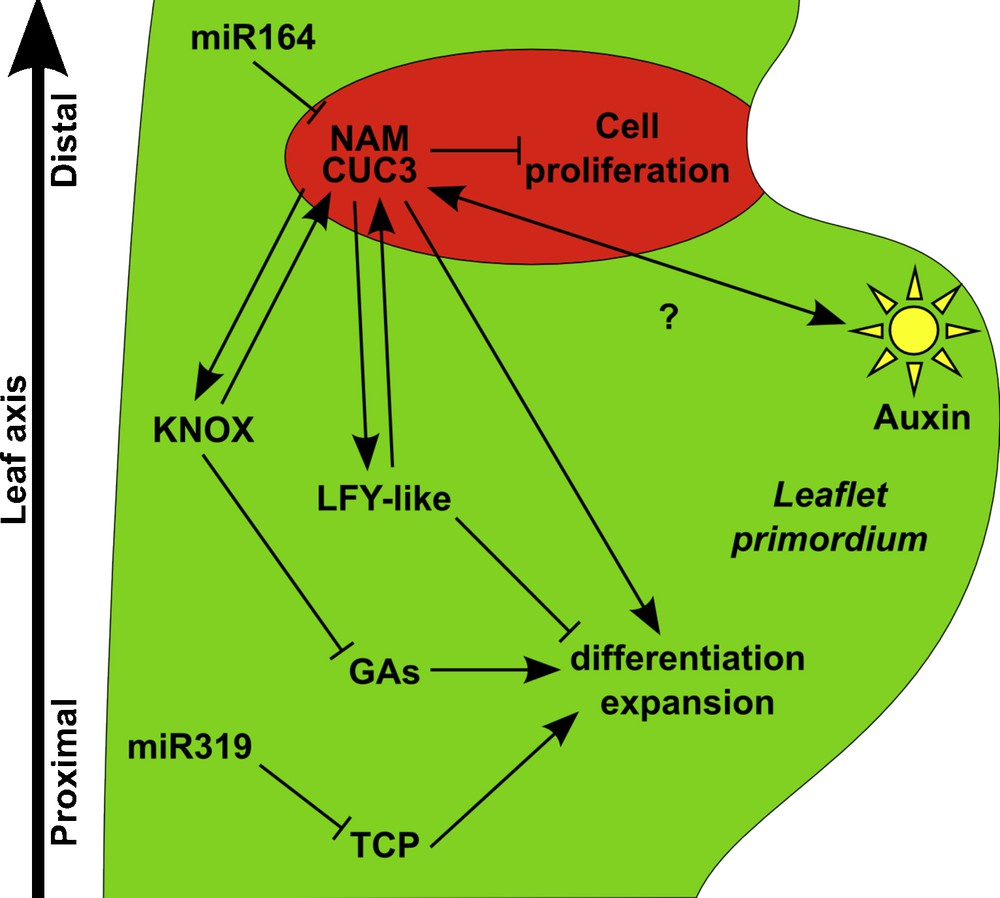

Genetic and molecular network controlling leaflet formation. Leaflet formation requires the maintenance of an undifferentiated environment to which contribute the KNOXI, LFY-like and TCP pathways. Action of the KNOXI factors is mediated by an inhibition of the Gibberellin (GA) pathway, while the TCP genes are negatively regulated by the microRNA, miR319. The site of leaflet initiation is determined by local accumulation of auxin (sun diagram). NAM/CUC3 genes are expressed in the distal boundary of the incipient leaflet (represented in red), where they locally repress cell proliferation and thus lead to the formation of groove. NAM genes are negatively regulated by the microRNA, miR164. NAM/CUC3 genes contribute to leaflet formation, possibly via a positive feed-forward loop with the KNOXI and LFY-like pathways.

In addition, to the KNOXI/GA pathway, tomato leaflet formation is also controlled by the TCP gene LANCEOLATE (LA). The expression of this gene gradually builds-up during leaf development, and may, like its Arabidopsis orthologue CIN, trigger growth arrest and differentiation. Precocious expression in the semi-dominant Lanceolate (La) allele that carries a mutation in the miR319 binding site leads to the formation of simple tomato leaves [100]. It is suggested that the LA gene defines a developmental window during which leaflet initiation is possible.

Despite the widespread association of KNOXI expression with compound leaf development [95], an alternate pathway has been revealed for some species. The initial observation that KNOXI expression is absent from developing compound primordia of pea [101] was recently enlarged to several members of a Fabaceae sub-clade that, in addition to the pea, includes fava pea and alfalfa, and that diverged 39 million years ago from other Fabaceae [102]. What is controlling leaflet initiation and formation in species of this clade? The answer to this question came from the identification of the gene affected in the pea unifoliata (uni) mutant that develops simplified leaves. UNI codes for the pea orthologue of the LEAFY (LFY) and FLORICAULA (FLO) genes that are required to specify the identity of the floral meristem [103,104]. In the pea, UNI has conserved its role in the control of floral development but, in addition, it is also required for maintaining leaf primodia cells in an undifferentiated state to allow compound leaf formation (Fig. 6). The contribution of LFY orthologues during compound leaf development has been shown for alfalfa that, like the pea, does not express KNOXI genes in their leaves [105], and also in the tomato, a species that expresses KNOXI genes during leaf development [106]. This suggests that the KNOXI and LFY pathways cooperate to enable compound leaf development, and that the relative contribution of each of these pathways varies depending on the species [107].

5.2 Organizing the outgrowth of new structures

Whereas the two pathways described above may explain the higher organogenetic potential of compound leaves, other factors are required to organize growth into the new structures that will form the leaflets. First, auxin, whose role in leaf primordium initiation and marginal serrations has been described above, is also involved during compound leaf formation (Figs. 5 and 6). More precisely, peaks of auxin response contribute to the outgrowth of leaflet primordia, whereas repression of the auxin response is required to inhibit outgrowth of the regions between leaflets (Fig. 5B) [108,109]. Second, orthologues of the Arabidopsis CUC genes are required for proper individualization of the leaflets. These genes show a conserved expression pattern in the axils of the outgrowing leaflets and their inactivation leads to leaflet fusions (Fig. 5B) [87,88]. In addition, inactivation of these genes leads to a reduction in the number of leaflets, thus revealing a promoting effect of the CUC genes on leaflet formation, a role that could be based on a positive feedback loop between the CUC genes and the KNOXI and/or LFY pathways (Fig. 6) [88].

5.3 Simple leaves versus compound leaves

The relationship between simple and compound leaves has long been a matter of debate [5]. Two opposite hypotheses have been proposed. The first one suggests that each leaflet of a compound leaf is homologous to a simple leaf, and that a compound leaf is equivalent to a compressed shoot. The second hypothesis suggests that leaflets result from extreme dissections of the leaf margins, and that the entire compound leaf is homologous to a simple leaf. Does the recent knowledge gained in leaf development help to discriminate between these hypotheses? During compound leaf development, the redeployment of the CUC/auxin/KNOXI/GA regulatory modules that are active in the meristem supports the hypothesis of a shoot-like identity of compound leaves. This identity, however, is only partial as compound leaf primordia do not express stem cell markers characteristic of the meristem [97]. Alternatively, serrations can be transformed into leaflets [97,110], and the auxin/CUC module is involved in both serration and leaflet formation, supporting the homology between these two structures. Taken together, these observations suggest that instead of a unique model for all compound leaves, these structures may arise through different developmental paths that converge to generate mature structures with comparable architectures. The repeated independent apparition of compound leaves during evolution also supports this idea [95].

6 Conclusion

Leaf development, from its initiation to growth and differentiation, is an excellent model to address fundamental issues of biology such as the generation of complex forms and their evolution. During the last years, important progress has been made in the identification and functional analysis of genetic and molecular regulators of leaf development. This research has revealed a surprisingly limited set of players, that can either play the same game with slightly different rules (during adaxial-abaxial leaf polarization, for instance), or play different games with similar rules (during the formation of different compound leaves, for instance). Understanding the differences in the rules, and how they modify the behaviour of the players to generate different games is the next challenge.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anne Plessis, Elizabeth F. Crowell and Michael J. Harrington for their helpful comments on the manuscript.