1 Introduction

Since the recent focus on animal communication networks, empirical and experimental as well as mathematical approaches have shown that individuals interacting with conspecifics use elaborate signalling strategies [1–3]. However, the emergence of these behaviours remains poorly understood. The study of parent–offspring relationships in birds may offer an opportunity to fill this gap [4]. In most bird species, offspring solicit parental feeding by performing demonstrative acoustic and visual signalling (begging behaviour, [5]). Within broods of several chicks, between-sibling competition in addition to the well-known “parent–offspring” conflict can both drive the dynamics of the family communication network [6–9]. Other factors such as the presence of predators may complicate the pattern [10–12]. With a time scale spreading from hatching to juveniles’ fledging, the parent–offspring communication network represents an interesting paradigm to decipher the developmental timing of signalling strategies in an interactive context.

In birds, begging behaviours have been the subject of numerous empirical and theoretical investigations [8]. Parent–offspring conflict suggests that chicks’ solicitation may be greater than is optimal for the parents [6]. However, this conflict can show a stable resolution: begging intensity and frequency may represent an honest cue of the need of young with parents responding in proportion [5]. Besides being possibly in conflict with parental interests, a chick may compete for food with its siblings. Parental food supply may be limited – from the chicks’ point of view at least –, a situation that can increase competition within the brood [7]. In some species, these conflicts may result in the death of some of the chicks [8]. Visible expressions of intra-brood competition can be fight for getting the closest position to the feeding parent, exaggeration of begging signals and physical aggression between siblings [8]. In this context, parents and offspring constitute a complex communication network with multiple signallers interacting together [4]. In spite of the efforts that have been performed to decipher the various strategies used by the network protagonists, the developmental aspects have been almost neglected up to now. However, it should be of primary importance, given the considerable changes that affect chicks’ biology (e.g., in terms of morphology, alimentary need, behavioural repertoire and many other aspects) during their breeding period. It is then poorly known how and in what extent behavioural strategies change from hatching to fledging. These changes are of course driven by the dramatic maturation events that affect growing chicks. These events are the result of both internal (genetic) and external (e.g., parental response to chick's signals) factors. In the present study, we propose to describe this kind of behavioural change in the chicks of the Black-headed gull Larus ridibundus.

In the Black-headed Gull, parents respond to chick solicitation by regurgitating food onto the ground. This specificity means that, conversely to situation occurring in many birds, Black-headed Gull parents do not allocate food to each chick individually. By monitoring both chick behaviour and parental response, a recent study [13,15] has shown that parents adjust their response – in terms of number of regurgitations – to the nest begging intensity. That is, parents are sensitive to the overall begging signal that emerges from the nest whether it comes from one isolated chick or from several chicks begging together. Moreover, sibling chicks apparently take into account this nest-adjusted parental response by synchronizing their begging signals, thus limiting individual effort. The study [13,15] focused on 8- to 15-days old chicks, and thus the ontogeny of this process – how the synchronization between chicks arises – is unknown. The present article investigates this question by monitoring broods of Black-headed Gulls from hatching to nest emancipation.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area and study species

The fieldwork was carried out at La Ronze pond (Forez plain 4° 13′ 33″ East longitude and 45° 34′ 31″ North latitude, France), a 12 ha pond which supports a large colony of Black-headed Gulls (4000 breeding pairs). Clutches of this species typically contain three eggs [14,16]. However, as nests with two chicks are the most typical in our study area, we chose to focus on two-chick broods for the present study. The Black-headed Gull is a semi-altricial species: chicks remain in the nest until the age of 3 weeks and both parents participate in chick rearing. Three age stages (each of about one week long) are commonly used to describe the nestling period: downy chicks (stage 1), chicks with first white feathers on the abdomen (stage 2), chicks with feathered wings and first black stains on the head (stage 3) [15,17].

2.2 Behavioural observations

Each nest studied (n = 5) was marked individually with a numbered plastic stake and monitored from egg laying to chick emancipation. Chicks (n = 10, two birds per nest) were individually identified by two bands (a metallic band numbered according the standard of the Museum national d’histoire naturelle and a coloured band to allow visual identification at a distance). Observations were conducted from a floating hiding place, remaining at 3–5 meters from the nest. Broods were observed during one hour twice a day over a 3-weeks breeding period, for a total of more than 650 begging sessions. Daily observations were organized in two periods (morning: 7–14 h and afternoon: 14–18 h), with a balanced pattern between nests to avoid pseudo-replication, meaning that the order of observations of the five nests permuted from day to day.

Gull begging displays involve visual and acoustical components [16,18]. The following 1–4 level ethological scale adapted from [13,15] was used to qualify the intensity of a begging bout of an individual. Whenever a chick begged, we get the score of its begging behaviour by noting the number of hunched postures (HP) and of beak stimulations (BS), and the rate (low LO = calls emitted during less than 30% of the begging bout duration, medium ME = calls emitted during 30 to 60% of the begging bout, or high HI = calls emitted during more than 60% of the begging bout) of calls. The 1–4 scores were defined as follows:

1 = (no HP + 1 BS) or (1 HP + no BS) + LO.

2 = (1 HP + 1 BS) or (no HP + 2 BS) or (2 HP + no BS) + LO or ME.

3 = (1 HP + 2 BS) or (2 HP + 1 BS) or (2 HP + 2 BS) + ME.

4 = (1 to more than 2 HP + 3 or more BS) or (3 or more HP + 1 to more than 2 BS) + HI.

When two chicks begged together, the total begging intensity emerging from the nest was given by the sum of both individual begging intensities obtained with the ethological scale.

As mentioned in the introduction, Black-headed Gull chicks may beg alone or together. During observations, three different kinds of begging bouts were thus noted: solitary begging of either a junior or senior chick and synchronized begging of both chicks. Begging efficiency was assessed by monitoring parental response (food regurgitation or not).

2.3 Statistical analysis

The respective numbers of begging situations (solitary or synchronized) were summed per brood and per day according to the nestling stage and compared using Wilcoxon matched pair signed ranks test. The same test allowed the comparison of chick begging intensities during synchronized begging sessions. Efficiency in eliciting parental regurgitation and begging intensity distribution were respectively compared between the various types of begging bouts using chi-square tests. Finally, we used a Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA by Ranks test to compare begging intensity distributions at different stages.

3 Results

3.1 Frequency and intensity of individual and synchronized begging sequences

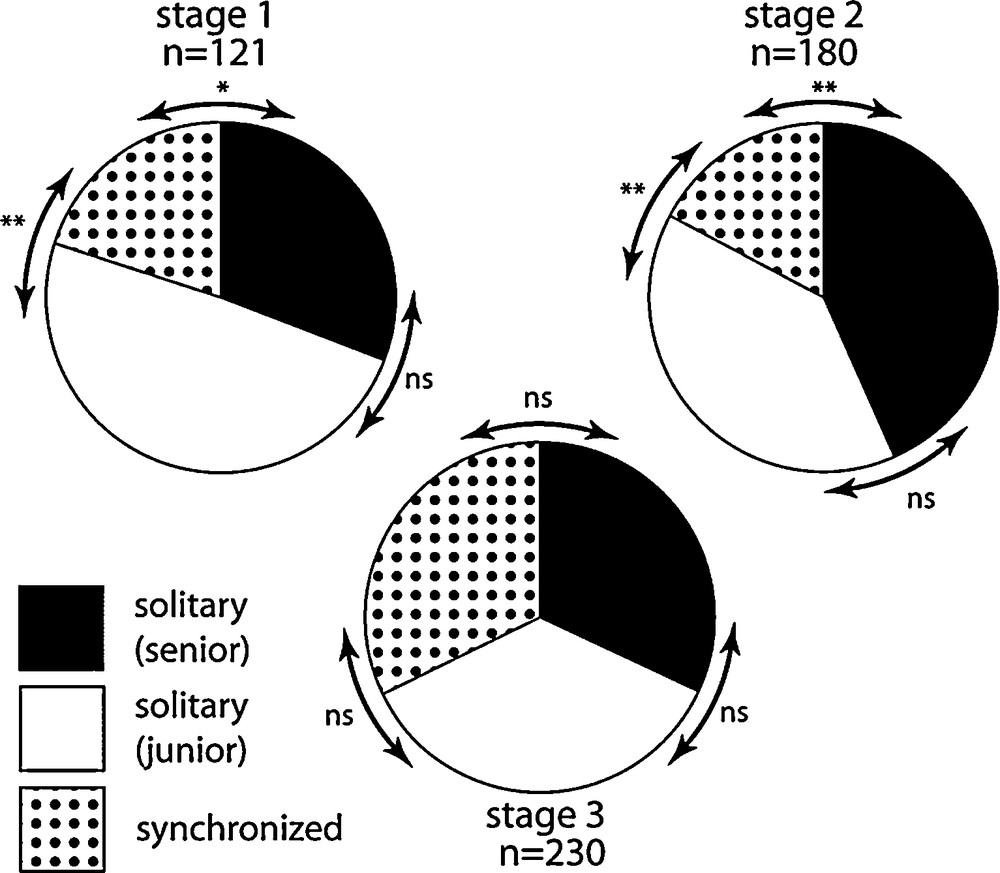

Fig. 1 reports the relative frequency of individual and synchronized begging sequences as a function of nestling stage. Although chicks preferentially begged alone at stage 1 and 2, synchronized begging emerged at this age (proportion of synchronized begging is significantly less than junior and senior chicks solitary begging, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranks test, P < 0.05 for each comparison, see Fig. 1 for quantitative values). However, the frequency of synchronized begging events strongly increased during stage 3. At this age, a chick – either the junior or the senior one – shared about 50% of its begging sessions with its sibling (Fig. 1).

Frequency distribution of solitary (junior and senior chicks) and coordinated begging events over the three stages of the nesting period (n = number of observed begging events). Whereas solitary begging predominates during the two first developmental stages, the relative importance of simultaneous begging increases during the third stage.

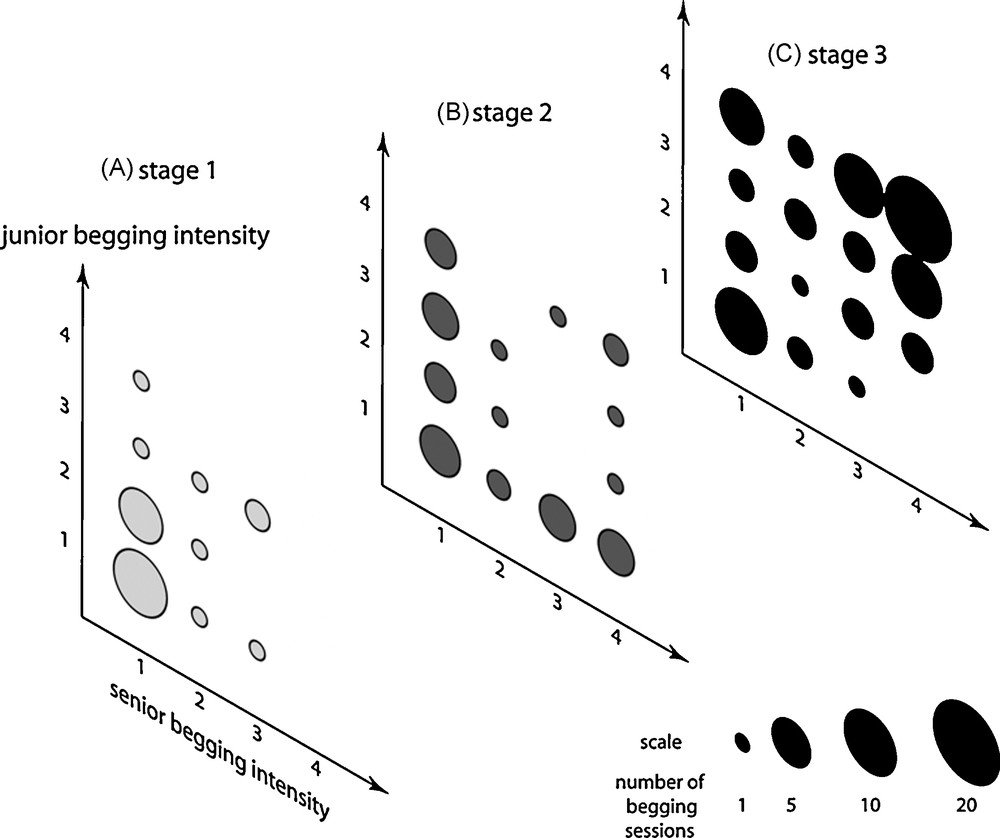

When begging alone at stage 1, the junior chick demonstrated a higher begging intensity than the senior chick (chi-square test, P = 0.029). Moreover, this difference of investment between chicks was perceptible, but not significant, when comparing intensities during synchronized begging sessions (Fig. 2A, Wilcoxon test, P = 0.09). Conversely, at stage 2, the senior chick increased overall begging intensity to the level of the junior chick (chi-square test, P = 0.31 for solitary begging; Wilcoxon test, P = 0.85 for synchronized begging, Fig. 2B). However, stage 2 begging sessions were mostly asymmetrical, combining a high begging intensity of one chick with low intensity from the other. Thus alternating behaviour occurred from each sibling during stage 2 (Fig. 2B). At stage 3, junior and senior chicks still showed different begging intensities. However, the pattern was modified when junior and senior chicks often begged together at a high level (Fig. 2C). As a consequence, the total level of begging intensity emerging from the nest raised considerably at this age (medians = 3, 4 and 6 respectively at stage 1, 2 and 3; comparing stage 1 vs. stage 2: P = 0.11, comparing stage 2 vs. stage 3: P = 0.005, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA by Ranks test).

Distributions of begging intensities for senior and junior chicks during coordinated begging events over the three stages of the nesting period. The apparition of coordinated sessions of high intensity is to be noted at stage 3.

3.2 Parental response

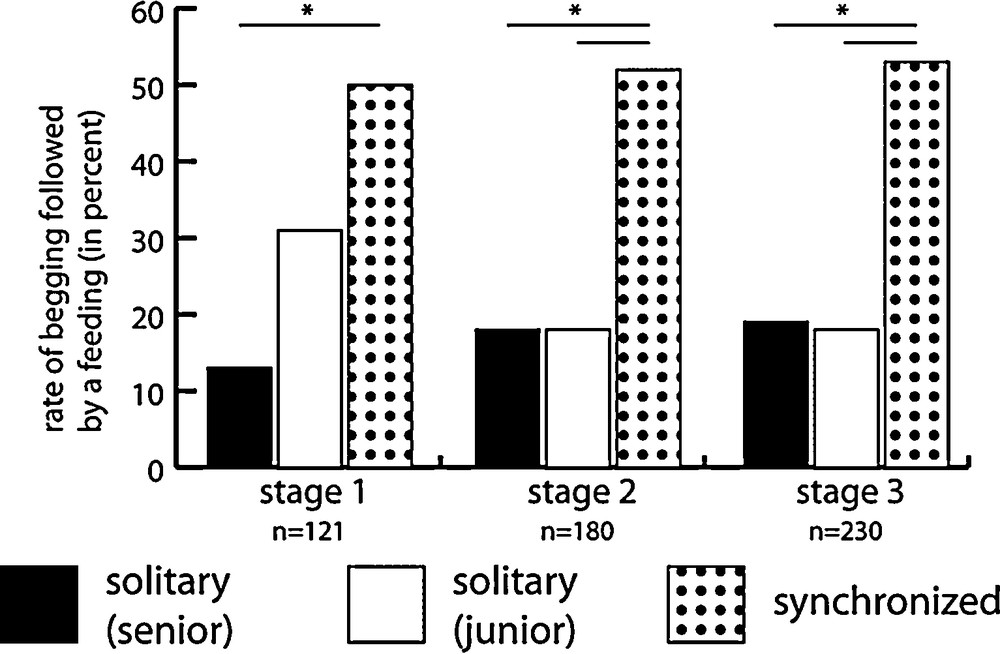

Except for the stage 1 junior chick, synchronized begging events are by far more efficient than solitary events in eliciting parental response (chi-square test, P < 0.01 at stage 1, and P < 0.001 at stages 2 and 3; Fig. 3). Indeed, synchronized events elicit parental regurgitation in more than 50% of cases whereas solitary begging hardly reaches 20% success. The efficiency of the stage 1 junior chick when begging alone (about 30% success) is likely linked to its high-intensity solitary begging.

Parental response to solitary and coordinated begging over the 3 stages of the nesting period. Coordinated begging is always more efficient in eliciting parental regurgitation.

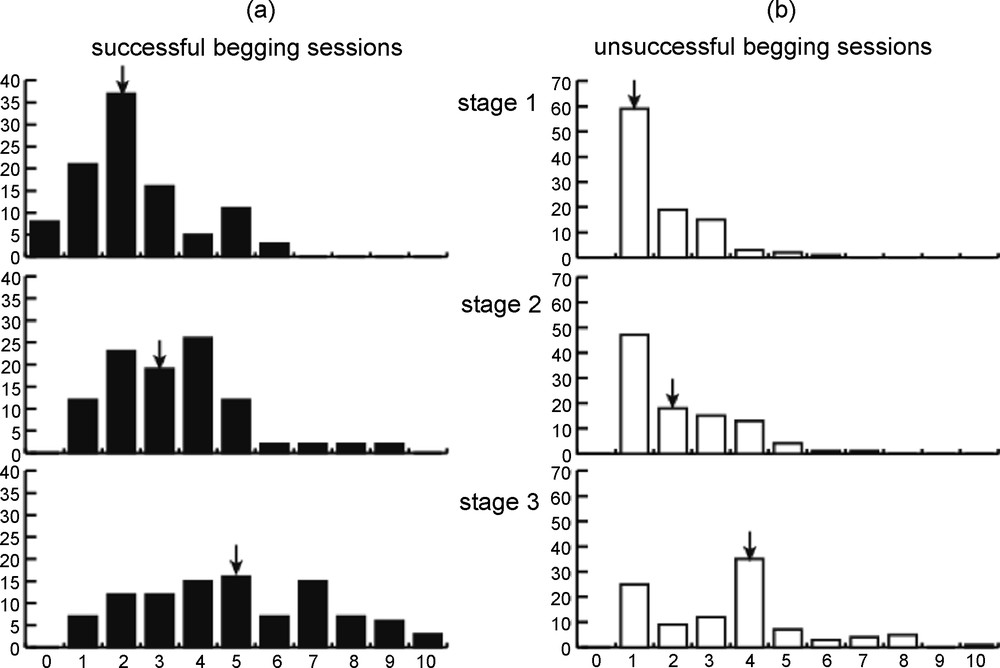

As illustrated by Fig. 4, parental response threshold rises with chick age. The older the chicks, the higher the parental threshold is, meaning that parents become more reluctant to respond to begging events of low total intensity as chicks grow up (stage 3 different form stage 2, P = 0.01, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA by Ranks test).

Frequency distributions of successful begging sessions over the 3 stages of the nesting period. Arrows indicate median values of distributions.

4 Discussion

The present longitudinal study shows significant changes in gull chick begging behaviour and parental responses over the nestling period. Although the small sample size incite to caution (5 nests monitored – but more than 650 begging events observed), the main finding is the development of coordinated begging bouts of high intensity. High-intensity begging behaviours appeared as soon as the end of the first week in the nest, but their coordination between the two chicks emerged during the last week of the nestling period. The most parsimonious explanation for a high coordination between chicks could be the increasing of the frequency of begging behaviours with age: if chicks beg more often, they would increase their chance to beg together. However, as there is usually 3–5 begging events/hour, each lasting around 1 minute, high proportions of synchronized begging are unlikely to be explained by chance only (for further considerations on this aspect, see [13,15]).

Previous observations on the same species have revealed another aspect of begging coordination when comparing nests with one, two or three nestlings; the more siblings there are, the more they coordinate their begging while decreasing the number of individual begging bouts [13,15]. In the Black-headed Gull, begging behaviour thus becomes a collective enterprise as described with banded mongoose Mungo mungo in a slightly different context [17,19]. The age-linked increase of this behavioural coordination may be related to modifications of the parental response threshold to chick begging. When the brood is less than one week old, parental regurgitations occur after weak begging sessions, whereas only intense begging is able to elicit parental response at stage 3. It is striking that this rise in parental threshold co-occurs with the qualitative coordination of begging behaviour. Such coordination increases the whole-brood begging intensity, and it is known that the rate of parental food delivery to nestling broods by parents is positively related to the total begging intensity by the brood ([13]; the present study; for examples in other species, see e.g. [18–20]).

It is generally thought that resolution of intrafamilial conflict depends critically on two mechanisms: (i) how changes in parental investment supply affect begging demand; and (ii) how changes in demand affect parental investment supply [21]. In this way, our observations reveal a possible adaptive response of offspring begging strategy to parental response. Whether begging by bird nestlings is primarily a solicitation of parental care based on degree of need or competition with siblings to exploit parental response to the loudest caller depends on whether and how parents control the allocation of provisioning [22]. A characteristic feature of the Black-headed Gull feeding behaviour is that parents regurgitate food on the nest ground and they do not, like passerine species for instance, allocate food individually to each chick. Although in the absence of individual food allocation, parents may be considered as passive providers, they could exert some influence on offspring behaviour when significantly favouring coordinated versus individual begging. Our results show that this trend is present from the beginning and across the whole rearing period spent in the nest, suggesting an effect of parental choice being imposed on the nestlings. This constraint on chicks may be more pronounced as chicks grow up since parental response threshold to begging intensity increases with time. In response, chicks adjust their begging behaviour by way of greater coordination. Likely driven by parental pressure, this adjustment should involve learning processes [23–25].

Our study provides the opportunity to compare the evolution of begging behaviour between junior and senior chicks. Overall, both chicks follow the same pattern, preferring synchronous begging especially at stage 3. However, there behaviour differs at stage 1, where junior chick begs more often and more intensively than its senior sibling. This result is in line with other works that revealed that the larger and competitively superior nestling often begs less than its nest mates [23,24,26–29]. A previous study [23] suggested that from the start, late-hatched nestlings experience severe competition and so learn that parental rewards are gained only after intense solicitation. In the Black-headed Gull, this divergence in begging patterns between senior and junior nestlings disappeared during the second stage of chick development, due to an increase in begging effort by senior chicks. To our best knowledge, the sole example of the same process of begging re-equilibration has been described in crimson rosella Platycercus elegans [30].

In line with recent works [31–34], the present study emphasizes that the dynamics of begging behaviour is a complex phenomenon, likely to be largely influenced by parental behaviour. Through favouring synchronized begging across the whole rearing period in the nest, Black-headed Gull parents may play a major role in the emergence of this behaviour among chicks. This supports the idea that nestlings can follow sophisticated conditional strategies and that their begging behaviour, far from being innate and stereotyped, may show large amount of learning plasticity.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank J.D. Lebreton and P.A. Crochet for their help in the field, and M. Dorkenoo for statistical advice. This work was supported by the université de Saint-Étienne and Saint-Étienne Métropole. NM is funded by the Institut universitaire de France.