1 Introduction

In Drosophila early development, bicoid mRNA of maternal origin is deposited in one of the poles of the egg, determining the anterior tip of the embryo and the position of the head of the larvae [1–4]. The deposition of mRNAs occurs during oogenesis by the mother's ovary cells and is transported into the oocyte along microtubules [5–8]. Initially, the oocyte has only one nucleus; however, after fertilization and deposition of the egg, nuclear duplication by mitosis is initiated, without the formation of cellular membranes [9]. During the first 14 nuclear divisions of the developing embryo, bicoid mRNA of maternal origin is translated into protein in the ribosomes and accumulates near the external nuclear walls of the recently formed nuclei, Fig. 1.

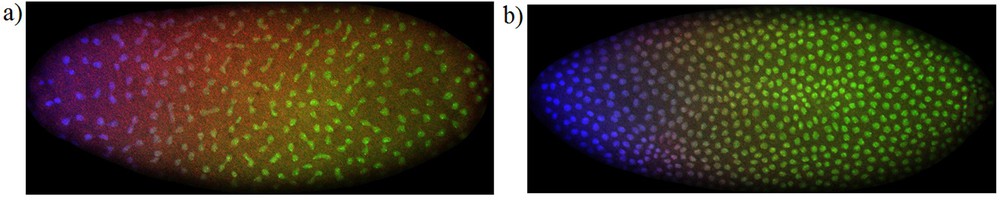

(Color online) Bicoid protein gradients: distribution of Bicoid (blue), Caudal (green) and even-skipped (red) proteins in the embryo of Drosophila, during interphase following the cleavage stages 11 (a) and 12 (b). The images were obtained from the FlyEx database, [10–14], and correspond to datasets ab18 (a) and ab17 (b). These proteins are translated from mRNA of maternal origin and accumulate around the syncytial nuclei. The absence of Bicoid and Caudal proteins in the inter-nuclear regions in the cytoplasm shows that Bicoid and Caudal proteins have very low mobility, contradicting the hypothesis of diffusion for Bicoid and Caudal proteins. Masquer

(Color online) Bicoid protein gradients: distribution of Bicoid (blue), Caudal (green) and even-skipped (red) proteins in the embryo of Drosophila, during interphase following the cleavage stages 11 (a) and 12 (b). The images were obtained from the FlyEx database, ... Lire la suite

During the interphases following the eleventh nuclear division up to the fourteenth, the concentration of Bicoid protein distributes non-uniformly along the antero-posterior axis of the syncytial blastoderm of the embryo of Drosophila. The concentration of Bicoid protein is higher near the anterior pole of the embryo and its local concentration decreases as the distance to the anterior pole increases. This is called the Bicoid protein gradient [2,4]. Recently, bicoid mRNA gradients along the antero-posterior axis of the embryo of Drosophila have been observed [15], clarifying our current views about Drosophila early development.

To infer about the mechanism of establishment of antero-posterior protein gradients in Drosophila early development, several models have been proposed. Some are based on the hypothesis of protein diffusion along the antero-posterior axis of the embryo [16,17], others are based on the diffusion of mRNA of maternal origin [18–22].

To clarify the role of diffusion in Drosophila early development, we extend a pattern formation mode [19] to include diffusion for both bicoid mRNA and Bicoid protein. With this model, we evaluate the relative role of the diffusion coefficients of mRNA and protein.

2 mRNA and protein diffusion

We denote the local concentrations of bicoid mRNA and of Bicoid protein by R(x, t) and B(x, t), respectively, where x denotes the longitudinal coordinate of the embryo (x ∈ [0, L]) and t represents time. Typical embryo length is L = 0.5 mm. We consider that mRNA degrades with a fixed ratio d and the ratio of production of protein is proportional to the local concentration of mRNA. Assuming a diffusion mechanism for both mRNA and protein, the model equations describing the synthesis of Bicoid protein from mRNA are

| (1) |

| (1) |

The rate of production of protein is measured by the proportionality constant a. In model equations (1), both bicoid mRNA and Bicoid protein diffuse. We further assume that there are no fluxes of mRNA and protein through the embryo membrane (zero flux boundary conditions). At the beginning of Drosophila development, bicoid mRNA is deposited in some region of the antero-posterior axis of the embryo, and the initial concentration of Bicoid protein along the embryo is zero.

As our goal is to justify the existence of a steady Bicoid protein gradient [23], we have not included a degradation term for protein Bicoid in the model equations (1). The absence of degradation during the first 13 nuclear cycles has been reported by several authors [23,24]. However, this does not exclude the possibility of protein degradation in later stages of development [25].

For a given initial distribution of bicoid mRNA, and after some time, a steady non-zero concentration of the Bicoid protein is reached. The protein gradient is steady during the nuclear cycles 11–13, [23], that last 33 minutes, [26]. At the steady state, the time derivatives in the model equations (1) are zero. As the first equation in (1) is independent of protein B, and after reaching the steady non-zero concentration of Bicoid protein, it can be shown that the bicoid mRNA concentration in the model equation (1) is zero, R = 0 [19]. In the embryo, at the protein Bicoid steady state, there is no more conversion of bicoid mRNA into protein Bicoid, the morphogenetic process is over. This stage defines the limit of validity of the model (1).

Since R = 0 at the steady state, according to (1), the concentration and spatial distribution of Bicoid protein obeys to:

Assuming that DB > 0, from this last equation and from the zero flux boundary conditions, it follows that the steady-state distribution of the Bicoid protein is constant along the embryo. Thus, the assumption that both mRNA and protein diffuse implies that the concentration of Bicoid protein is constant along the embryo, contradicting the existence of a gradient of Bicoid protein.

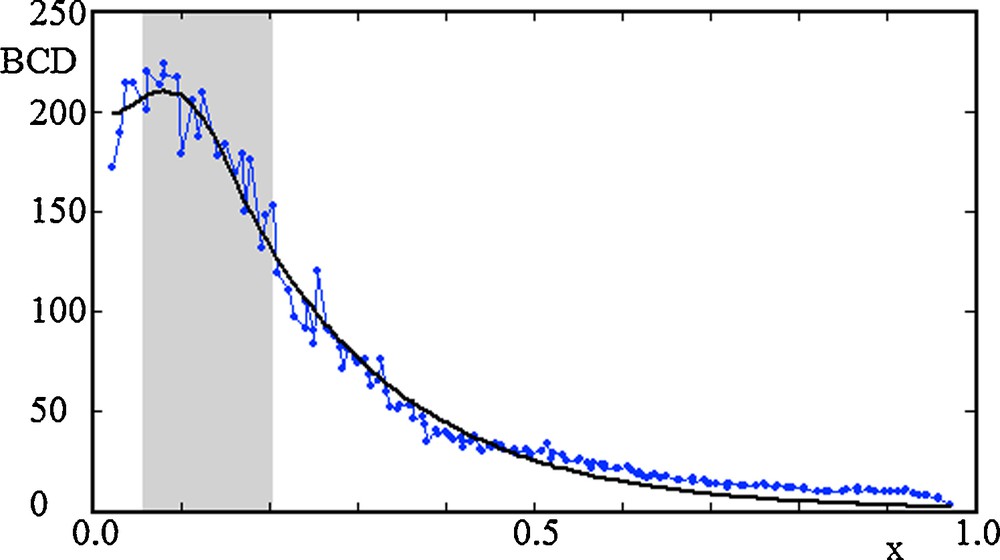

With the choice DB = 0, the bicoid mRNA diffusion model (1) explains the observed gradients of the protein Bicoid [19], fitting the experimental data with high accuracy, both in time and along the antero-posterior longitudinal axis of the embryo, Fig. 2. The results of the mathematical model and this analysis lead to the conclusion that mRNA diffusion is the main mechanism responsible for the establishment of protein gradients.

(Color online) Concentration of Bicoid protein (BCD) along the antero-posterior axis (x) of Drosophila, at nuclear cycle 13. The length of the embryo has been rescaled to the value L = 1. The data in the figure (connected dots) is from the FlyEx dataset ab16. The data points of the Bicoid gradients are taken from a region centered around the central antero-posterior axis of the embryo. The thick black line are the best fits of the experimental data with the steady-state solution prediction derived from model equation (1), and with Bicoid protein diffusion set to zero, DB = 0. The grey regions show the initial localization of bicoid mRNA, and have the fitted values l1 = 0.056 and l2 = 0.147. The parameters of the fits are Aa/d = 684.2 and

(Color online) Concentration of Bicoid protein (BCD) along the antero-posterior axis (x) of Drosophila, at nuclear cycle 13. The length of the embryo has been rescaled to the value L = 1. The data in the figure (connected dots) ... Lire la suite

Experimental observations of protein localization during cleavage stages 11–14 corroborate the model conclusions described above. The images in Fig. 1 show that Bicoid protein is always localized around the syncytial nuclei where ribosomes are positioned. This protein localization feature is seen in all the embryo data sets of the FlyEx database (data sets ab18, ab17, ab16, ab12, ab14, ab9, ad13, ab8) [10–14]. The images show that Bicoid protein is not present in the internuclear spaces in the cytoplasm, showing that diffusion of Bicoid protein plays no role in the establishment of the Bicoid gradient. Since diffusion is a dispersal effect homogenizing concentrations in a media, the mathematical model, alongside the theoretical arguments presented here are consistent with the mechanistic interpretation of diffusion [27], and with the observed data of Fig. 1.

Several authors have analysed the mRNA localization mechanisms in the embryo of Drosophila experimentally. Recently, the bicoid mRNA gradient has been observed experimentally [15]. The observation of rapid saltatory movements of injected bicoid mRNA into the embryo of Drosophila, followed by dispersion without localization, has been reported [28]. Other diffusion effects observed on the mRNA motion have been reported for the nanos mRNA [29]. From a theoretical point of view, Saxton argued that the relatively small size of mRNA suggests that random diffusion and specific anchoring to the cytoskeleton in a target area might suffice for localization in the syncytial blastoderm [5].

Further extension of the mRNA diffusion model has been applied to the description of morphogenetic gradients in other maternal and gap-gene families of mRNAs and proteins. The same modeling with mRNA diffusion has been applied to the description of gradient formation of Caudal [18,22], Tailless, Hunchback and Knirps proteins [20,21]. Calibration of a mRNA diffusion model with experimental data makes it possible to predict the spatial position of the segment of the Huckebein protein [21], along the embryo of Drosophila. In all these cases, the model predictions accurately fit the experimental data, both in time and along the antero-posterior longitudinal axis of the embryo, with relative errors of the order of 5%.

3 Discussion

We conclude that, in Drosophila early development, mRNA diffusion is the main morphogenesis mechanism that consistently explains the establishment of Bicoid protein gradients. The coexistence of mRNA and protein diffusion prevents the establishment of protein non-uniform gradients in Drosophila early development. Numerical simulations [18–22] have shown that the diffusion of mRNAs of maternal origin is sufficient to explain the establishment of steady non-uniform gradients of maternal and gap-gene families of proteins along the embryo of Drosophila.

Protein gradients were first observed in proteins of maternal origin and the current view is that proteins diffuse through the syncytial Drosophila embryo [3,4]. However, as we have shown, mathematical models contradict this hypothesis. The experimental data depicted in Fig. 1 shows that the internuclear space on the syncytial blastoderm of the embryo of Drosophila is always free of proteins with maternal origin, contradicting the assumption of protein diffusion before the establishment of a steady gradient.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the constructive comments of the referees on the first version of this paper. Their suggestions improved significantly the results of the paper, helping to justify biologically some modelling assumptions. I would like to thank IHÉS for its hospitality and support, as well as Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia for its support.