1 Introduction

Sex has been termed the “queen of problems in evolutionary biology”, and how sex is determined in the animal kingdom has always been a major question with “debates on the origin of the sexes that took place long before the beginning of the scientific era” [1]. Indeed, since the beginning of this “scientific era”, important knowledge has been acquired on this topic with, for instance within the quite recent “genetics era”, the important discovery of sex chromosomes, followed by the identification of the master gene governing the acquisition of the male sex in human and in mouse [2]. Despite huge efforts in the last decades, however, our knowledge of master genes controlling genetic sex-determination has remained limited [3]. The relative scarcity of information on sex-determination (SD) genes is mainly due to major scientific and technical barriers that hinder the precise identification of these SD genes in many species. Classical approaches for the characterization of SD genes have always relied on the intimate knowledge of a group of specialists working on very few species. Their success has often been guided either by educated guess and candidate gene approaches [4,5], or by tedious searches for sex-linked markers with various time-consuming methods [6–9]. The relatively few species investigated now with regards to SD genes have been selected based on practical interests (for instance species easy to maintain in captivity [8–12]) or economical (for instance important aquaculture species [5,13–15]) and these species always had preexisting genetic and/or genomic information available. There is then an urgent need to address the question of the evolution of SD genes using a large-scale, unbiased approach that would not rely on or need such previous knowledge.

2 A glimpse into sex-determination and SD genes evolution in vertebrates with a focus on fish species

The field of evolution of sex-determination and SD genes in vertebrates has long been shaped by knowledge gathered in mammals, because previously this was the only group for which the master SD gene, SRY, was known [2]. The generally accepted hypothesis for the mechanism by which an SD gene can evolve, namely by allelic diversification of an autosomal gene towards a male or female sex-promoting function, and subsequent maintenance of the male-specifying allele as a male dominant SD gene on the proto-Y chromosome, was satisfied by SRY and its supposed progenitor SOX3 [3]. In 1999, dmrt1 was found as a candidate gene for SD in chicken, which proposed a different mechanism, namely dosage sensitivity [16]. In 2002, the first fish SD gene was identified in the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Unexpectedly, this gene, called dmrt1bY or dmy [7,10], arose by a gene duplication event from the autosomal dmrt1a gene being transposed to the proto-Y, adding another evolutionary mechanism for the emergence of an SD gene. Full sequencing of the male-specific region of the Y chromosome (MSY), the first to be known after the human Y, revealed that several additional predictions of the general theory of Y chromosome evolution were also not fulfilled, like stepwise diversification on an autosome, recombination suppression, degeneration of Y-linked genes, and accumulation of male-favoring genes [17]. This finding raised doubts about a unifying concept for the evolution of SD genes and heterogametic sex chromosomes.

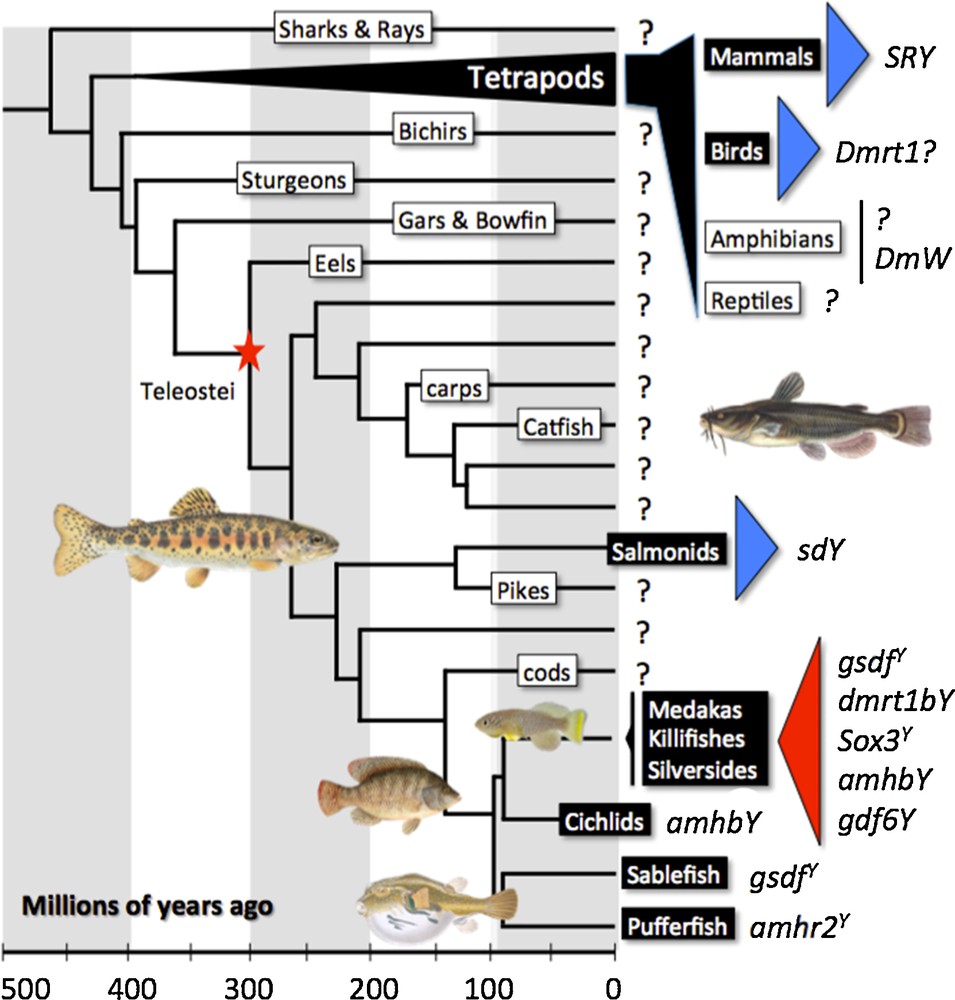

Fish are uniquely suited to study the evolution of sex-determination and SD genes (Fig. 1). Comprising about half of the 60,000 species of vertebrates, fish show also the greatest variety of sex-determination. Unisexuality, simultaneous and consecutive hermaphroditism, environmental, and genetic sex-determination are found in different, often closely related species and the distribution of various mechanisms follows no obvious phylogenetic pattern. With respect to genetic SD, it became quickly clear after its first discovery that dmrt1bY of medaka is not the master SD gene of fish in general [14]. Despite huge efforts over more than a decade, SD genes of only a few more species have been added to this list, and all those species have strong monogenic sex-determination. In a sister species to medaka, O. luzonensis, and also in sablefish, Anoplopoma fimbria, allelic variations of a TGFβ member gene named gsdfY determines male development [8,13]. In Takifugu rubripes (pufferfish) as well, allelic variation at a single nucleotide position of the amh-receptor 2 gene, again a downstream component of the SD cascade in other vertebrates, controls phenotypic sex [6]. In the Patagonian pejerry, Odontesthes hatcheri, a Y-linked duplicate of the amh gene drives male sex-determination [5], a situation that mirrors the evolutionary scenario of the medaka SD gene. The same SD gene is also found in the tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, but in that species it is a Y chromosome missense SNP on a tandem duplication of amh that drives sex-determination [15]. Interestingly, another TGFβ member, namely gdf6Y has also been found as a potential SD in the killifish Nothobranchius furzeri [11], suggesting that members from the TGFβ pathway are often recruited as SD genes in vertebrates. In rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, gene duplication and neofunctionalization led to the emergence of the SD gene [14], but totally unexpected and contrary to the situation in all other vertebrates for which information on proven or candidate SD genes exists, the duplicated gene sdY is not derived from a previously known component of the SD cascade, but from the interferon regulatory factor 9, which normally functions in the context of immunity.

Vertebrate sex-determining genes play musical chairs. Evolution and diversity of sex-determining genes in vertebrates (see text for details). Species or groups of species with an already known or highly suspected sex-determining gene are shown in black boxes. Blue triangles represent master sex-determining genes with a certain degree of evolutionary conservation. Red triangles represent group of species with a high turnover of sex-determining genes. The red star shows the position of the teleost-specific whole-genome duplication.

The current state of knowledge about the evolution of SD in vertebrates – last but not least influenced by the recent findings in fish – has resulted in a very unsatisfying situation. With the examples of male-biasing SD genes identified to date, it is rather impossible to derive a comprehensive understanding of processes and mechanisms that lead to the evolution of new SD genes and to evaluate the prevalence and general relevance of different systems. We do not know whether dosage sensitivity of master SD genes is an enigmatic case that is restricted to the avian lineage or is used more generally. Gene duplication and neofunctionalization is appearing now as a more frequent process to create novel SD genes, but the three fish species in which it has been found might be special in some way and bias our view by chance due to the low number of known SD genes in general. It can also be asked whether teleost fish that experienced in their evolutionary history whole-genome duplication and certain lineage-specific additional ones profit from this genomic situation with respect to the evolution of new SD genes. Regarding female heterogamety, there is so far no example of a predicted dominant female-determining SD gene in fish that could add to the single case of Xenopus laevis, where dominant-negative action of a W-linked truncated dmrt1 gene is proposed to suppress a postulated default male development in WZ frogs [4]. A totally unresolved complication comes from several reports where, even in cases that appear to be clear monogenic SD, polymorphic autosomal modifier genes or environmental influences can modify or override the sex-chromosomal mechanisms. It can only be vaguely hypothesized that these findings indicate transition states between SD switches, and again the prevalence of such situations is absolutely unclear. It is obvious that the first step towards a better understanding of SD mechanisms and how new SD genes evolve is to characterize SD genes in more species, study their inheritance, and eventually illuminate their mode of action.

3 The RAD-Sex approach: a Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS) screening for exploring the diversity of sex-determination systems in fish

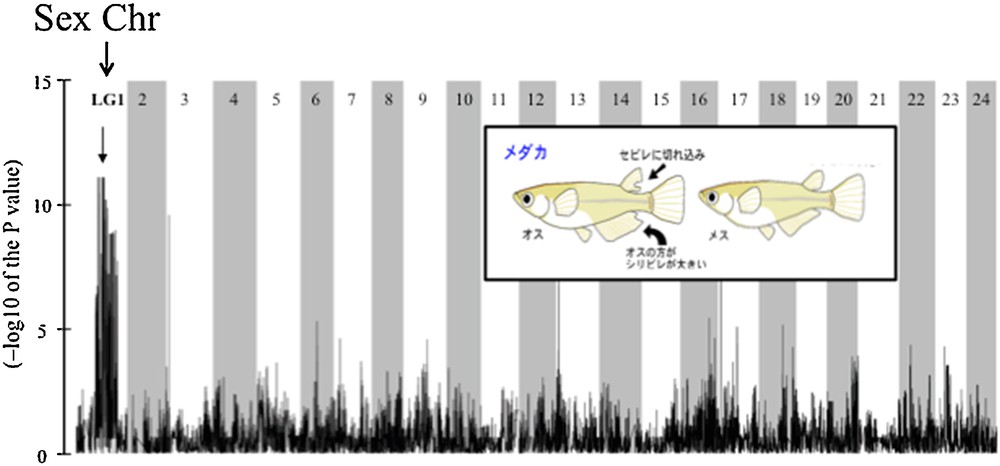

Restriction Associated DNA tags (RAD-tags) are sequences adjacent to restriction enzyme cutting sites that can be assayed by a next-generation sequencing technique known as RAD sequencing method (RAD-seq) [18]. RAD-seq has been shown to be an extremely powerful method for sampling the genomes of multiple individuals in a population. Because it does not require preliminary information on the genetics or the genome of the studied species, this approach is especially interesting for developing genetic analyses in the context of non-model organisms [19]. This technique was recently applied with success to search for sex-specific sequences in Gecko lizards [20] and for a sex-determining locus in zebrafish, in which strain-specific sex-determination systems were characterized [21,22]. To serve as an additional proof of principle, we applied this approach to the medaka, Oryzias latipes, which has a strong well-characterized genetic SD system [7,10,17]. The main idea was to investigate if RAD-seq was equally efficient in identifying sex-specific sequences close to dmrt1bY, the known SD gene in that species [7,10], using as starting biological material individuals from an outbred population of fish and not a genetic mapping family panel as was used in the case of the zebrafish [21]. To that end, fin clips were sampled from 31 phenotypic males and 32 phenotypic females of the Carbio strain of medaka. Genomic DNA was extracted from these samples and RAD library construction was carried out with each individual given a distinct barcode. Samples were sequenced in two lanes of Illumina HiSeq2000 using single-end 100-bp reads. This dataset analysis allowed us to characterize more than 600 sex-polymorphic RAD-tag sequences among an overall total of 120,000 genetic markers. Most of these sex-polymorphic sequences map to the central portion of medaka linkage group LG1, the region that distinguishes the Y from the X chromosome (see Fig. 2). Among these sex-polymorphic RAD-tag sequences, 58 were sex-specific, i.e. the sequences were only present in males and totally absent in all the females. When mapped onto the medaka genome, 22 of these sex-specific RAD-tags were found to be on the Y chromosome (LG1) and 30 on unordered scaffolds, probably due to an incomplete assembly of the medaka Y chromosome. Among these sex-specific RAD-tag sequences, nine mapped to the Y non-recombinant sex-specific region (GenBank ID: AP006153) including two sequences that were less than 1 kb downstream of the 5′ end of the dmrt1bY medaka sex-determining gene (GenBank ID: AY129241) [10]. These results clearly demonstrate that the RAD-Sex approach is highly efficient because it enabled the identification of sex-specific sequences located very close to the previously known SD gene even in a GWAS that does not allow a simultaneous genetic mapping of the RAD-tags. It should be noted, that our analysis, although conducted on a species with a sequenced genome, did not use the genome sequence for the analysis of sex-associated RAD-tags: the genome sequence only provided validation of the proof of principle. This comparatively inexpensive approach can thus be applied to multiple species in a relatively high throughput project, without the need for obtaining biological materials from controlled genetic crosses that could be difficult to obtain in some species. This approach is also possible in species with no genetic or genomic information available, thus providing a special opportunity to develop an evolutionary-based project that can investigate the sex-determining system in a vast array of species.

Distribution of Restriction Associated DNA-tag (RAD-tag) markers along the 24 chromosomes of the medaka sequenced genome. The significantly sex-biased markers identified mid LG1 (chromosome Y) as the location of the sex-determining locus. Markers retained in this analysis have been scored in at least 25 individuals within the population.

Applying this approach to a large panel of species should provide a first evolutionary picture of SD genes answering simple but important questions like: how many evolutionary innovations can be characterized i.e., novel SD genes, how many “usual suspects”, i.e. duplications of genes already known for their implication in the sex differentiation cascade, and how prevalent are gene duplications as primary events generating novel SD genes and thus how relevant is this evolutionary scenario beside the classical hypothesis of allelic diversification and the so far enigmatic situation of SD by gene dosage to explain the diversity of SD mechanisms. These questions on the evolution of SD genes have currently only been addressed for a narrow phylogenetic range, but never for a broad spectrum of taxa that represent a considerable fraction of the diversity and adaptations of a whole class of the chordate phylum. Such information will inform an essential question in evolutionary biology, foster genetics and developmental biology, and last but not least provide immediately useful information for better management of economically important fish species in fisheries and aquaculture.

4 Conclusion

Sex-determination is a very basal and ubiquitous developmental process and the fact that it is so variable even between closely related organisms poses many fascinating questions. A number of scenarios and hypotheses have been put forward to explain which evolutionary forces could favor such transitions and turnovers (for a review, see [23]). They range from fitness advantages of a new sex-determination or its linkage to genes that are favorable to one sex or antagonistic to the other sex, over mutational load on the old, disappearing sex-determination gene to scenarios that consider that neutral or non-adaptive processes of genetic drift, mutation and recombination can be instrumental in creating new sex-determination systems. For all these hypotheses, which appear to a certain extent opposing or even contradictory, examples to support them can be found. A single one obviously cannot explain all the different cases of sex-determination systems and the many instances of turnovers and transitions. Rather than being alternatives, they may be complementary. To further our understanding of the trajectories that lead to the evolution of diverse sex-determination mechanisms and sex chromosomes we need more detailed molecular knowledge about the molecular biology of these various mechanisms and about the ecology and population genetics under which they occur.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by funds from the “Agence nationale de la recherche” (France) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (ANR/DFG, PhyloSex project, 2014–2016).Funding: FACAD.