1 Introduction

Human-induced climate changes are altering the patterns of mean and extreme temperatures across the globe, modifying the biogeographic distributions and abundance of species, especially of the ectothermic ones [1–3].

Among these, reptiles living at high latitudes or altitudes are particularly susceptible: their reproductive strategies in fact have become seasonal [4–6] and require fluctuating temperatures as ‘zeitgeber’ [7]. The importance of a suitable temperature is demonstrated by the careful selection of the nest-site by a gravid female [6,8,9].

Laboratory-based approaches have attempted to characterize the thermal limits and constraints behind a successful reproductive performance. The experimental results have demonstrated that environmental temperature controls performance-related traits, including morphology and behaviour [10–13]. Therefore, any dramatic thermal fluctuations or periods with extreme temperatures might have serious consequences on the reproductive fitness and, ultimately, on population survival [14–16].

In general, it has been demonstrated that juveniles and young adults display a wider thermal niche than embryos and adult spawners [17]. As an example, for the lizard Podarcis muralis, the optimal incubation temperature is 26 °C, and a critical threshold already occurs between 29 and 32 °C [10]. In this species, the low tolerance range is probably due to the effects that temperature changes exert on the egg incubation period and the size, locomotion and growth rate of the hatchling [10,18].

Although the fundamental role of environmental thermal parameters is known to determine offspring sex, behaviour and fitness in reptiles, little information, if any, is available about the onset of cell and tissue induced by thermal stress.

In this work, we examined the effects of continuous (from oviposition to day 20 post-oviposition [po]) or temporary (5 days from day 5 or 15 po) thermal stresses on the development of the wall lizard Podarcis sicula. Either cold (15 °C) or warm (30 °C) stresses were applied; the effects on morphogenesis and on the expression of HSP70 were analysed. HSP70 is a molecular chaperone involved in cellular stress response [19,20], and for this reason it is widely used as a biomarker for assessing thermal stress in a broad range of animals [21], including reptiles [22]. A P. sicula HSP70 cDNA fragment was cloned, sequenced and used in in situ hybridization analysis.

The results confirmed the influence of thermal stress on embryo development and indicated that HSP70 are involved in the molecular mechanisms activated by cold stress and have therefore an active part in the occurrence of the observed negative effects.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethical procedures

All the procedures were conducted following the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation of the Italian Department of Health and were organized in order to reduce stress and the number of animals used. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the University of Naples Federico II (Permit Number: 2011/0014483).

2.2 Animal housing and egg incubation

Gravid P. sicula females (30 specimens) were captured between May and June in the outskirts of Naples. Females were kept in a terrarium maintained under natural conditions of temperature (26 °C by day and 20 °C by night) and photoperiod, in accordance with the institutional guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals. The lizards were fed live mealworms three times a week and water was provided ad libitum. Daily check of the terrarium provided freshly laid eggs; each female laid an average of 18 eggs [23]. The eggs were pooled and randomly allocated in seven jars containing uncontaminated natural soil. For thermal treatments, the first two groups of eggs were incubated at constant temperatures of 15 and 30 °C, respectively, since the day of oviposition. The other four groups were exposed to thermal stress for 5 days, in accord to the convention that, for prolonged exposure, a 10% of the organism's life span is significant [24]. In Podarcis, embryo development lasts for about 55 days [25,26]. As a consequence, another two groups of eggs were incubated at natural thermal regime for 5 days and then exposed for 5 days at an incubation temperature of 15 °C or 30 °C. The last two groups of eggs were incubated at natural thermal regime for 15 days and then exposed for 5 days at an incubation temperature of 15 °C or 30 °C. Control embryos were incubated at 26 °C (day) and 20 °C (night). For each thermal treatment, 8 eggs were used. Soil water lost as vapour was reintroduced by daily nebulization with distilled water. Eggs were removed from terrariums and washed to remove soil traces. Embryos recovered from shells were checked for vitality (heart beating) or gross morphological alterations, staged [25,26] and processed for cytological investigations.

2.3 Light microscopy

Viable embryos were fixed in Bouin's solution and processed for paraffin wax embedding according to routine protocols [27]. Sections were stained with haematoxylin-eosin to show general morphology [27] or used for in situ hybridization analysis.

2.4 Cloning of lizard HSP70

Total RNA from 20-day-old embryos developed under natural conditions was extracted according to the Tri-Reagent (Sigma Aldrich) protocol. The concentration and purity of RNA dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water were determined by UV absorbance spectrophotometry; RNA integrity was checked using 1% formaldehyde–agarose gel electrophoresis. An aliquot (5 μg) of this total RNA was reverse-transcribed. Briefly, RNA was denatured by heating at 65 °C for 5 min and then incubated in 20 μL of reverse transcriptase (RT) buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.3, 3 mM MgCl2, 75 mM KCl) containing 0.5 mM of each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate [dNTP], 10 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 20 units of RNase inhibitor (Superase-In, Ambion), 1 mM of oligo(dT)-adaptor primer (5′-CGGAGATCTCCAATGTGATGGGAAATTC(T)17-3′), and 200 units of Superscript II reverse transcriptase enzyme (Life Technology), for 42 °C for 60 min, and successively at 70 °C for 15 min to inactivate the enzyme. The resulting first-strand cDNA was amplified by PCR using forward (5′-AGCCCAAGGTGCAGGTGGAGTAC-3′) and reverse (5′-ACAGCTCTTTGCCATTGAAGAA-3′) specific primers for HSP70. The primers were designed on a fragment of the nucleotide sequence of chicken HSP70 available at the EMBL Nucleotide Database. PCR reaction mixture contained 2 μL of first-strand cDNA, 1× PCR buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.3, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2 mM MgCl2], 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.4 mM each of specific primers, and 2 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Euroclone). The reactions were carried out in a GeneAmp thermal cycler (Applied Biosystem), with an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 4 min; 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR product was cloned using the StrataClone TA PCR cloning kit (Agilent), and multiple independent clones were sequenced by PRIMM. The identity of the clones was evaluated by matching the sequences to the nucleotide/protein sequences available at the EMBL Database. The P. sicula HSP70 mRNA fragment obtained by PCR is available in the GenBank database under the accession number LT219470.

2.5 HSP70 mRNA detection by in situ hybridization

Sections (5–7 μm) were placed on superfrost glass slides (Menzel-Glaser, Germany), fixed in paraformaldehyde 4% in PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4) pH 7.4 for 20 min and incubated in PK buffer (Tris-HCl, 0.2 M, pH 7.4, EDTA 0.01 M, pH 8, proteinase K, 10 μg/mL, H2Odepc) at 37 °C for 15 min. After washing in PBS, they were incubated at 42 °C for 90 min in a pre-hybridization mix containing formamide, SSC 4× and 1× Denhart's solution. Hybridization was carried out at 42 °C overnight using the dig-labelled cDNA probe encoding the P. sicula HSP70 fragment. Sections were washed in SSC 2×, in buffer I (Tris-HCl 0.1 M, pH 7.5, NaCl 0.1 M, H2Odepc) and in buffer I containing a blocking reagent (0.5%). Digoxigenin was revealed by incubating sections overnight with an AP-conjugated anti-dig antibody diluted 1:400. Slides were washed in Buffer I, incubated with levamisole-Tween20 1× for 15 min and exposed with BM-Purple. Dig-labelled HSP70 cDNA probe was generated by PCR using the DIG High Prime DNA labelling and detection starter kit I (Roche). For negative control, the hybridization solution did not contain the cDNA probe.

3 Results

3.1 Temperature and hatching success

At natural thermal regime, the embryonic survivorship on day 20 was 100%. No vital embryos were observed in eggs incubated for 20 days at the constant temperatures of 15 or 30 °C. Similarly, no embryos survived if exposed for 5 days to 30 °C, no matter if the thermal shock was given after 5 or 15 days from oviposition; embryos died even when exposed to 15 °C after 5 days of incubation at natural temperatures. In some cases, embryo remnants were unrecognizable, in others they were clearly recognizable but head and/or trunk and/or appendages were badly underdeveloped or altered.

By contrast, shock at 15 °C for 5 days did not result in lethality when given to embryos incubated for 15 days at natural temperature: in this case, 90% of survival was registered. These embryos, though clearly formed, showed a significant percentage of malformations that occurred in brain, especially in telencephalon, diencephalon and optic roof of mesencephalon, in retina, and in trunk organs.

3.2 Morphological analysis of brain in cold-treated embryos

In 20-day control embryos, incubated with a natural thermal regime, the two telencephalic hemispheres (Fig. 1A) contained dorsoventrally elongated ventricles, thinning ventrally due to the prominent dorsal ventricular ridge, and septal and striatal areas. A thin dorso-medial pallium was recognizable. The grey matter was regularly arranged to form a continuous ventricular zone. The diencephalon (Fig. 1B) was a single dorsoventrally elongated vesicle, with a thin epithalamic roof delimiting a dilated epithalamic vesicle. The grey matter was particularly abundant in dorsal habenulae and, more ventrally, in the areas of the future nuclei rotundus and reticular. The mesencephalon appeared particularly prominent from the head profile (Fig. 1C); it showed a clearly recognizable dorsal optic tectum and ventral foot. Posteriorly it laid on the rhombencephalon. Caudally, the optic tectus was invaginating medially so to divide the large III ventricle (Fig. 1D). The tectal grey matter was regularly organized forming a continuous and rather thick ventricular zone ending, ventrally, in the prominent torus semicircularis (Fig. 1C). More externally, it was covered by a cortical marginal zone, made of white matter that was continuing ventrally in the brain stem (Fig. 1C–D). Here, scattered aggregates of grey matter (Fig. 1C) or nuclei anlages (Fig. 1D) were observed. The rhombencephalon (Fig. 1C) showed the typical organization with a large dorsal IV ventricle lined ventrally by the developing ventricular zone of grey matter. More ventrally, the white matter formed a thick body, containing medially an evident grey reticular zone. Laterally to the encephalon, inner ear anlages were clearly recognizable (Fig. 1C–D).

Cross-sections of the brain vesicles in 20-day post-oviposition lizard embryos. A. Telencephalon: pallium (p), striatum (st), septum (s) and ventricle (v). Grey matter forming a ventricular zone (vz). Retina (r). B. Diencephalon: epithalamus (ep), prominent habenulae (ha), hypothalamus (hp) and ventricular zone (vz). C. Mesencephalon: tectum (t), torus semicircularis (ts) and abundant white matter in the pars basalis (pb); rhombencephalon (ro) with IV ventricle (v), inner ear anlage (e). D. Detail of mesencephalon: tectum invaginating medially (arrow) and differentiating ventricular zone (vz). Cortical marginal zone (cz), torus semicircularis (ts) inner ear (e) and nuclei (n) anlages, IV ventricle (v). Haematoxylin-eosin staining. Bars: A–B, 150 μm.

The cold-shock did not cause a significant delay of the developmental processes: limb buds, used as main reference organ for staging, were essentially identical to those present in control animals. However, significant alterations were observed in the development of telencephalon for 7 of the 8 embryos examined. These included a reduction of septal and striatal white matter (3 embryos; Fig. 2A), a profound alteration of septal and pallial structures (3 embryos; Fig. 2B) and, in 1 case (Fig. 2C), a severe dorsoventral compression of the hemispheres.

Morphological alterations induced by a 5-day cold stress in the developing brains of 20 days post-oviposition lizard embryos. A. Telencephalon: ventricles and the grey matter of the ventricular zone (vz) are normal; the striatal (st) and septal (s) masses are poorly developed, the entire vesicle protrudes from the head profile and the vascularization is increased (*). Retina (r). B. Telencephalon with disorganized pallium (p). Notice the folded retina (r), striatal mass (st) (*), increased vascularization. C. The diencephalon (dc) is altered, showing two large lateral masses (*) of disorganized cells, compressed telencephalon (tlc); folded retina (r). D. Diencephalon without dorsally open ventricle (*). Notice also the small protrusion (arrow) present in one of the mesencephalic hemispheres. E. Asymmetrical mesencephalon (msc) and rhombencephalon (ro). Notice the unilateral torus semicircolaris (ts) and ear anlage (e). F. Mesencephalon compressed dorsoventrally. Also notice the asymmetrical torus semicircularis (ts) and the indentation present in the dorsal roof (arrow). Ventricular (vz) and cortical marginal zone (cz) appear normal. Haematoxylin-eosin staining. Bars: 150 μm.

The diencephalon showed marked alterations in 5 out of 8 embryos. These were associated with marked telencephalic alterations (Fig. 2C); in 4 cases they were represented by a thickening of the vesicle walls that invaded the ventricle (Fig. 2C). Areas of necrosis and tissue disorganization were also observed (Fig. 2C). In the remaining embryo, the ventral and lateral diencephalon was regularly organized but the ventricle appeared completely open dorsally, due to the lack of an epithalamus, skull roof and skin (Fig. 2D).

The mesencephalic vesicle was altered in all embryos showing evident unilateral loss of shape (Fig. 2E). In several embryos, asymmetrical indentations (Figs. 2F and 6G) and ridges (Fig. 6G) were observed in the tectum.

Localization of HSP70 transcripts in 5-day-cold-treated 20-day post-oviposition lizard embryos. A. Labelled proximal retina (r); vitreous humour (vh). B. Folded and labelled proximal retina (r). C. Detail showing the sudden border between labelled and unlabelled areas; notice the labelled ganglion cell layer (gcl). Inner nuclear layers (inl). D. Labelled folded retina (r). E. Telencephalon; labelled ventricular zone (vz); pallial (p) and striatal (st) areas are unlabelled. Ventricle (v). F. Dorsoventrally compressed telencephalon with asymmetrically labelled ventricular zone (vz). G. Diencephalon with asymmetrically labelled ventricular zone (vz). Mesencephalon also shows an asymmetrically labelled ventricular zone (vz). Notice the fold (arrow) and the dorsal indentation in the tectum (small arrow). H. Diencephalon with amorphous thalamic masses (*); unlabelled epithalamus (ep) and folded retina (r). I. Mesencephalon; scarcely labelled torus semicircularis (ts). J. Labelled grey matter (*) in spinal cord. K. Gut; labelled tunica muscolaris (tm) and unlabelled mucosa (gm). L. Unlabelled renal tubules (rt). M. Unlabelled liver parenchyma (l).

Finally, cold-treatment induced occasional alterations in the rhombencephalon of two embryos. These consisted in a unilateral under-development, resulting in a loss of symmetry (Fig. 2E).

3.3 Morphological analysis of eyes in cold-treated embryos

In 20-day control embryos, incubated under natural thermal regime, the eyes were large, protruding from the head profile (Fig. 3A); the proximal portion of the retina was already stratified, the plexiform, nuclear and ganglion cell layers (Fig. 3B) being clearly recognizable.

Morphological alterations induced by a 5-day cold stress in the developing eyes of 20 days post-oviposition lizard embryos. A–B. Control. C–G. Cold-treatment. A. Cross-section of the head; telencephalon (tlc), optic nerve (o), stratified proximal retina (pr), vitreous humour (vh). B. Detail of the proximal retina showing the outer (onl) and inner (inl) nuclear layers, the outer (opl) and inner (ipl) plexiform layers, the ganglion cell layer (gcl) and the optic layer (ol). C–D. Folded proximal retina (pr) invading the vitreous humour (vh). E–F. Detail of the folds shown on Fig. 3C: layering is essentially maintained: inner nuclear layers (inl); inner plexiform layers (ipl); vitreous humour (vh). Pigmented epithelium (arrows). G. Detail of an unfolded tract. Inner nuclear layers (inl); inner plexiform layers (ipl); vitreous humour (vh). Pigmented epithelium (arrow). Haematoxylin-eosin staining. Bars: A, C: 150 μm; D: 100 μm; B–G: 50 μm.

In cold-stressed embryos, the eyes showed alterations mainly to the retina, that in 7 out of the 8 embryos examined appeared either unilaterally or bilaterally folded (3 vs. 4 embryos; Fig. 3C). In three cases, folds invaded almost entirely the vitreous humour (Fig. 3D); in all cases, cell stratification was maintained (Fig. 3E–G).

3.4 Morphological analysis of trunk organs in cold-treated embryos

In 15-day control embryos (Fig. 4A–C), the main trunk organs were already distinguishable. By day 20, the gut was formed by a thick mucosa, made of columnar cells surrounded by an already differentiating tunica muscolaris (Fig. 4D). The liver sinusoids (Fig. 4B) developed in a continuous parenchyma (Fig. 4E) and the kidney tubules (Fig. 4C) were more numerous and differentiated (Fig. 4F).

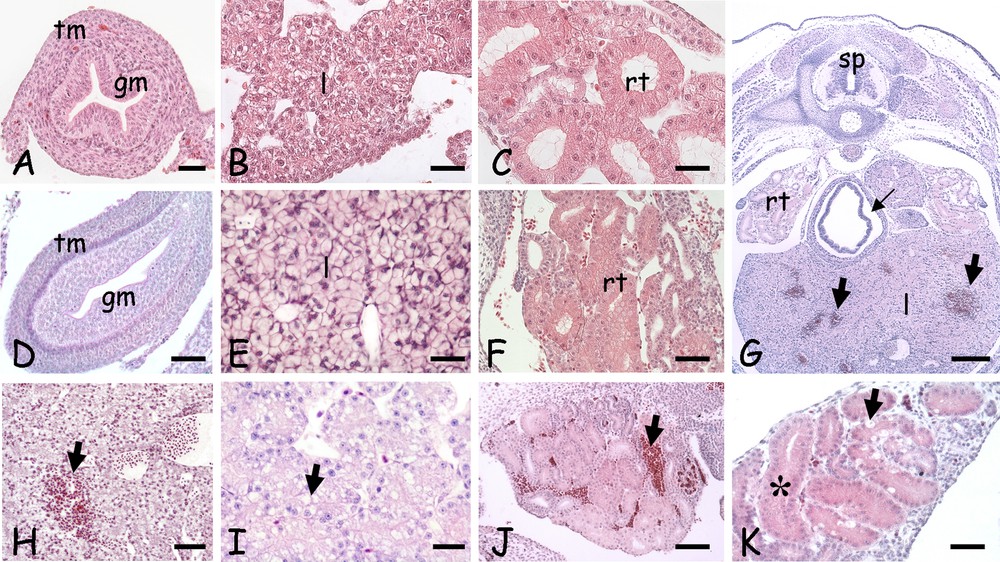

Morphological alterations induced by a 5-day cold stress in the trunk organs of 20 days post-oviposition lizard embryos. A–C. Control 15 days. D–F. Control 20 days. G–K. Cold-treatment. A. Gut; cross-section showing the tunica muscolaris (tm) and mucosa (gm). B. Developing liver cords (l). C. Undifferentiated renal tubules (rt). D. Gut; note the bilayered tunica muscolaris (tm); mucosa (gm). E. Liver parenchyma (l). F. Differentiating renal tubules (rt). G. Trunk, cross-section; haemorrhagic infiltrates in liver (large arrows) and seric infiltrates around the gut (small arrow). Spinal cord (sp); renal tubules (rt); liver parenchyma (l). H. Liver with haemorrhagic infiltrates (arrow). I. Vesiculated liver cells (arrow). J. Kidney; haemorrhagic infiltrates (arrow). K. Kidney; tubule cells with dense and vacuolated cytoplasm (arrow). Occluded lumens (*) can be observed. Haematoxylin-eosin staining. Bars: A, C: 10 μm; B, D–F, I, K: 25 μm; H, J: 50 μm; G: 100 μm.

In cold-stressed embryos, the liver (Fig. 4G–H) and the kidney (Fig. 4G and J) showed haemorrhagic infiltrates, and seric infiltrates were occasionally present in the gut (Fig. 4G). Damages were visible also at the cell levels: the hepatocytes were vacuolated (Fig. 4I), while in kidney the occlusion of the tubular lumen and/or cloudy degeneration were observed together with occasional hyaline droplet degeneration (Fig. 4K).

3.5 Expression and localization of HSP70 in cold-treated embryos

To evaluate gene the expression level and the localization of HSP70 transcripts in the developing organs of control and cold-stressed embryos, a cDNA fragment encoding the HSP70 gene was cloned and sequenced by RT-PCR. Specific forward and reverse primers were designed on homologous sequence of avian species (accession number FJ217667). Combining these primers, the PCR reaction gave rise to a 777 bp DNA fragment encoding a polypeptide of 258 amino acids, sharing 95% identity with the homologous regions of chelonian (accession number KJ683736) and crocodilian (accession number AB306279) HSP70s. The partial mRNA sequence of P. sicula HSP70 is available at the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases with the accession number LT219470.

The P. sicula HSP70 cDNA fragment was labelled with digoxigenin and used as a probe for in situ hybridization analysis, as described under Materials and methods.

In the early stages of development, under a natural thermal regime, HSP70 messengers appeared in somite cells on day 3 (Fig. 5A), in spinal cord neurons on day 5 (Fig. 5B) and in the retina, on day 15 (Fig. 5D). Here, the HSP70 mRNA uniformly distributed in the cells of the undifferentiated distal retina (Fig. 5E) while, in the layered proximal retina, messengers were concentrated in outer and inner nuclear layer cells (Fig. 5F). At this time, in both head (data not shown) and trunk organs (Fig. 5G), no messenger was observed.

Localization of HSP70 transcripts in 3 (A), 5 (B–C), 15 (D–G) and 20-day post-oviposition lizard embryos. A. Trunk, frontal section, 3 days post-oviposition (po); labelled somites (sm). Spinal cord (sp). B. Spinal cord, cross-section; labelled periventricular grey matter (*). Notochord (n). C. Unlabelled retina (r) and lens (l); vitreous humour (vh). D. Labelled retina (r) and lens outer epithelium (arrow). Vitreous humour (vh). E. Detail of distal retina with labelled undifferentiated cells (*). Pigmented epithelium (small arrow). F. Detail of proximal retina showing messenger localization in the inner nuclear layer (inl). G. Unlabelled renal tubules (rt), liver (lv) and lung (lg). H. Intensely labelled retina (r). Vitreous humour (vh). I. Detail showing the localization of labelling on the inner nuclear layer (inl). J. Telencephalon; labelled ventricular zone (vz), pallial (p) and striatal (st) masses. Notice labelling on differentiating skin scales (*). K. Diencephalon with labelled ventricular zone (vz). L. Mesencephalon; labelled ventricular (vz) and periventricular (pvz) zones. Few labelled cells are also present in the cortical marginal zone (cz, arrow). M. Detail of the medial portion; cortical (cz), ventricular (vz) and periventricular (pvz) zones. N–O. Differently labelled cortical marginal zones (arrows). P. Rhombencephalon; scattered labelling on the ventricular zone (vz). Ventricle (v). Q. Labelled spinal cord (sp) and cartilages of the developing vertebra (ve) and limb bud (lb). R. Unlabelled gut mucosa (gm) and renal tubules (rt); positive tunica muscolaris (tm). S. Unlabelled liver parenchyma (l).

After 20 days, in the retina, the inner nuclear layer became very intensely labelled with respect to the other retinal strata (Fig. 5H–I). In addition, transcripts appeared in the central nervous system vesicles. In the telencephalon, they were localized in the periventricular zone, in the dorsolateral pallium and, to a lesser extent, in the striatum (Fig. 5J). In the diencephalon (Fig. 5K), HSP messengers were evenly distributed on the periventricular zone; a similar situation was observed in the mesencephalon, in which a less intense staining was also present on the periventricular zone (Fig. 5L–M). In the marginal cortical zone, several sparse cells were labelled: their position changed in serial sections (Fig. 5L, N–O). Finally, in the rhombencephalon, a modest and scattered labelling was observed on the periventricular zone (Fig. 5P).

In the trunk, labelling was observed on the grey matter of the spinal cord (Fig. 5Q), on forming cartilages (Fig. 5Q) and on incipient gut tunica muscolaris (Fig. 5R). No staining was observed on renal tubules and gut mucosa (Fig. 5R) or on liver parenchyma (Fig. 5S).

In the 20-day embryos that had survived the 5 days at 15 °C, the localization of HSP70 mRNA showed several significant changes with respect to controls. In three animals, the retina, either normal (Fig. 6A) or folded (Fig. 6B–C), was labelled only proximally and, in one case, ganglion cells remained unlabelled (Fig. 6A). In the other five animals, the folded retina retained the typical labelling observed in controls (Fig. 6D).

In the brain, in the telencephalic hemispheres, labelling was observed on the periventricular zone, but not on the pallial and striatal cells (Fig. 6E). In the compressed telencephalon (Fig. 6F), labelling on the periventricular zone was asymmetrical. In the diencephalon, labelling on the periventricular zone was conserved in morphologically normal vesicles (Fig. 6G); in altered ones the epithalamus was often unlabelled (Fig. 6H). In the mesencephalon, the periventricular zone was usually labelled and the torus semicircularis usually scarcely labelled (Fig. 6I). In asymmetrical lobes (Fig. 6G), an asymmetrical labelling was usually observed.

The localization of HSP70 transcripts in the rhombencephalon, spinal cord (Fig. 6J), gut (Fig. 6K), kidney (Fig. 6L) and liver (Fig. 6M) did not differ from that observed in control embryos (Fig. 5).

4 Discussion

This study clearly showed that constant thermal stress (both cold and warm stresses) is lethal for P. sicula embryo, and that the early embryonic stages are more stenothermal than the later ones. This observation can be easily explained, considering that at oviposition embryos have just started neurogenesis and organogenesis [26]; hence any early interference results in profound pattern alteration.

Our results also demonstrated that hyperthermia has a more detrimental effect than hypothermia on the embryonic development: 15 days old embryos die if incubated at 30 °C, but survive at 15 °C. A negative effect, in term of hatching and/or occurrence of morphological alterations, has been reported in other oviparous vertebrates [28,29] and invertebrates [30], indicating that common mechanisms of heat-induced damage occur. In effect, it is known that an increase in temperature results in an uncontrolled protein unfolding and aggregation with multiple cell insult [31] and, also, in a decreased haemoglobin-O2 binding efficiency [32], with consequent alteration of the embryonic energy metabolism. Heat-induced teratogenic development has been observed also in mammals, for example in rat foetuses, where the severity of the abnormalities was evident relative to the increase of temperature, duration of heat shock and stage of development [33,34]. Morphological alterations in the nervous tissues and in the vascular endothelium have been demonstrated, indicating that changes have occurred at the cellular and molecular levels [35].

Though apparently viable, Podarcis embryos developed at a low temperature show severe morphological damage; in the nervous tissues primarily, where the encephalic vesicles and the retina are formed but visibly altered in size and/or shape. Interestingly, similar morphological abnormalities are observed in rat foetuses exposed to heat stress [34] and in lizard embryos grown in cadmium-contaminated soils [36,37]. This suggests that chemical and physical stresses interfere with brain development by altering similar pathways. In effect, in both cases, an explanation could be the change in vessel permeability and consequent alteration of protein passage through the blood-brain barrier [38–40]. Changes in vessel permeability and/or in circulation would also explain the seric and haemorrhagic infiltrates observed after hypothermia in the trunk organs [41], while cytoplasmic damages in kidney tubule cells can be attributed to an inhibition of the Na–K–ATPase pumps [42] and to the consequent loss in osmotic control at the local level.

Another possibility explaining the morphological alterations observed is that thermal stress has interfered at the transcriptomic level and, in particular, considering the lethality registered during the early developmental stages, on the expression of master control genes. A preliminary analysis performed on cold-stressed P. sicula embryos [43] has already demonstrated a downregulation of the expression of the gene Suppressor of Variegation 4-20 Homolog 1 (SUV4-20H1), a methyltransferase methylating histone H4 [44]. This result is in agreement with that found in Atlantic cod embryos, in which thermal stress alters the expression of genes involved in DNA methylation in a stage-specific manner [45]. Obviously, it cannot be excluded that other genes, such as transcription factors or functional proteins, might have also changed as occurring in cadmium-treated embryos [37,46].

Other genes whose expression may be altered, in particular upregulated, after thermal and chemical stressors are HSPs [47], molecular chaperones representing the major cellular protection to protein denaturing stressors [48]. In embryos, the data on their presence and induction in response to sub-lethal levels of stress are controversial [49]. Differential response among species would depend on the presence of a pool of maternal messengers. In the orphan embryos [50], the fertilized egg has sufficient HSP70 mRNA to handle potential stressors and the synthesis of new HSPs starts only later, serving specific developmental roles, such as lens differentiation in zebrafish [51]. In mouse, early embryos contain very few copies of HSP70 mRNA, but transcripts may be rapidly produced as early as the 4-cell stage [52].

In lizard, the spatiotemporal analysis of HSP70 gene expression during the development demonstrated the absence of a pool of maternal HSP70 mRNA. In the same embryos, on the contrary, a consistent pool of maternal mRNA encoding for the metallothionein, another pivotal member of the cytoprotective protein family, is present [26,53]. HSP70 mRNA was detected in P. sicula embryos as early as 3 days post-oviposition, in the developing somites and from day 5, in the spinal cord. However, other mesodermal derivatives, the kidney tubules, for example, remain negative as well as the encephalic vesicles, up to day 20. Similarly, the retina starts transcription around day 15, five days before the encephalic tissues from which is originated. Clarifying whether the protein is also present and where it localizes could help in understanding the differences observed in embryonic HSP70 gene expression.

In 20-day embryos, HSP70 transcripts become very abundant, being present in the grey matter of all encephalic vesicles and spinal cord, in the retina and in mesodermal tissues such as the muscolaris mucosa of the gut and the developing cartilages. Particularly interesting are the results obtained from the in situ hybridization on cold-stressed embryos. The evidence emerged is that thermal stress does not anticipate or induce de novo HSP70 transcription, a result confirmed in other animals [49,50,54]. Liver, gut mucosa, kidney tubules and the nervous white matter that were unlabelled in controls, remained unlabelled after stress. Interestingly, under cold-stress embryonic HSP70 gene expression seems to be silenced in the distal portion of the retina and silenced/delayed in the telencephalic and mesencephalic cortical areas. Noteworthy, in the latter the event is accompanied by more or less severe morphological anomalies. No differences in HSP70 gene expression were observed in the other organs.

At the moment, we cannot exclude that the differences in HSP70 expression in embryonic tissues are correlated with changes in the pattern of new and/or residual protein synthesis. Moreover, other member of the HSPs family can be constitutively expressed during lizard development, or being induced under cold stress, as observed in Xenopus laevis [49] and Caretta caretta [22] embryos after heat shock.

In conclusion, the data herein reported demonstrate that P. sicula embryos show a very narrow temperature range in which development can occur normally. Thermal stress during embryonic development therefore may be a critical factor for offspring loss, with consequent impact at the population level, especially in case of temperature increase. It has been demonstrated that female lizards exposed to chemical pollutants show a low fecundity [55,56], so it is easy to postulate that the combined effects of chemical and physical insults will threaten the survival of natural populations exposed to anthropic pressure.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.