1 Introduction

Formins are a large group of 120- to 220-kDa proteins that regulate the nucleation and assembly of actin fibres in response to several signals [1,2]. To date, 15 genes coding for formins have been identified in Mammals [3–5]. They were divided into seven subclasses based on the sequence similarities:

- • diaphanous (DIAs);

- • formins (FMNs);

- • FMN-like formins or formin-related proteins in leukocytes (FMNLs/FRLs);

- • Dishevelled-associated activators of morphogenesis (DAAMs);

- • formin homology domain proteins (FHODs);

- • delphilin and inverted formins (INFs) [6].

DAAM1 shows a typical formin structure, including the Formin Homology 1 (FH1) domain, which can interact with profilin, and the FH2 domain, which binds actin, allowing the nucleation of new filaments [1,2]. This protein is stabilized in an autoinhibited state due to the interaction between the diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID) at C-terminal and the GTPase-binding domain (GBD) at N-terminal [7]. DAAM1 switches to an active conformation upon binding at the C-terminal with the PDZ domain of Dishevelled 2, a phosphoprotein involved in the planar cell polarity (PCP) non-canonical Wnt pathway [8]. This frees the GBD domain and allows for its interaction with Rho GTPase [8,9], while actin is recruited at the FH2; RhoA, in turn, can activate Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) [10]. These events result in actin state modification and cytoskeletal rearrangement. Several studies have shown that DAAM1 participates in many essential biological processes, such as cytoskeletal organization in cell polarity, movement and adhesion during morphogenesis and organogenesis [11–16]. Although DAAM1 has been implicated in a variety of developmental processes, most frequently associated with central nervous system and heart morphogenesis [17–22], there is just little information about its role in adult tissues. We previously reported the possible involvement of this formin during the post-natal development of rat testis and in rat and human spermatozoa [23]. We showed that DAAM1 and actin shared their localization in the cytoplasm of germ cells, suggesting its role in the formation of complex structures, marked by a significant cytoskeletal remodelling, which enables germ cell separation protection and maintenance. Moreover, we found that DAAM1 localized in the flagellum of rat spermatozoa, while in human sperm it was retained inside the residual cytoplasmic droplets. In a further paper, we investigated the involvement of the testicular DAAM1 expression in the possible protective role of zinc against cadmium-induced male reproductive toxicity at adult age after maternal Cd and/or Zn exposure during gestation and lactation [24]. As of now, no reports have directly associated DAAM1 with the epithelial cells of seminal vesicles. These are exocrine glands that are part of the male sex accessory organs. These glands are present in most families of placental mammals [25] and produce, after testosterone stimulation [26] a fructose, citric acid, proteins and prostaglandin rich secretion that can reach more than 60–70% of the seminal plasma in humans [27]. During the exocytosis of these components, a great remodelling of cytoskeletal elements occurs, especially regarding actin and it is known that factors that participate in the same molecular pathways are expressed in other exocrine tissues: these include other formins, such as mDia [28,29], as well as several GTPases and Rho-related proteins [30,31]. Thus, to improve the understanding of the potential role of the formin DAAM1 in the cellular system, and in particular during the exocytosis events, in this work, we assessed the possible involvement of this protein in the secretory epithelium of mouse seminal vesicles, comparing its expression and localization with a fundamental component of cellular cytoskeleton, the actin filaments.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animal care and tissue extraction

Male C 57 black mice (Mus musculus) were housed under definite conditions (12D:12L) and were fed standard food and provided with water ad libitum. Animals were perfused with phosphate buffer saline, PBS (13.6 mM NaCl; 2.68 mM KCl; 8.08 mM Na2HPO4; 18.4 mM KH2PO4; 0.9 mM CaCl2; 0.5 mM MgCl2; pH 7.4) and then sacrificed by decapitation under ketamine anaesthesia (100 mg/kg i.p.) in accordance with national and local guidelines covering experimental animals. For each animal, seminal vesicles were dissected; one half was fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin for histological analysis, the other half was quickly frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C until RNA and protein extraction. Additionally, male Sprague–Dawley rats (Rattus norvegicus) were housed in the same conditions and testes were dissected, frozen and stored at –80 °C to be used as a positive control.

2.2 Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the samples using Trizol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 5 μg of total pooled RNA, 250 ng/μL oligo(dT)18,0.8 mM primer (Promega, Heidelberg, Germany) and 100 U Super-script II RT enzyme (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) in a total volume of 25 μL, according to the manufacturer's instructions. As a negative control, the reaction was carried out on the same RNA without using the reverse transcriptase enzyme (RT−). Two to three μL of the obtained cDNA template were then used for the PCR reaction as described by Chemek et al. [24]. Based on the published sequence of Mus musculus Daam1 mRNA (GenBank accession No. NM_026102.3), specific oligonucleotide primers were designed as follows:

Daam1 for: 5′-GCCATGTTTGCACTTCCAGC-3′ Daam1 rev: 5′-TCAGAATGAGCCAGGACATG-3′.

An appropriate region of Mus musculus Actin mRNA (Act; NCBI GenBank accession No. NM_007393.5) was amplified with specific oligonucleotide primers (Act for = 5′-CTTTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCTT-3′, Act rev = 5′-CTGCTTGCTGATCCACATC-3′) and used as control. The amplifications were carried out for 35 cycles, with denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 45 s and extension at 72 °C for 45 s. The expected PCR product sizes were 392 bp for Daam1 and 300 bp for Act, 391. The amplification products were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gel.

2.3 Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Mouse seminal vesicles and rat testes were lysed in a specific buffer (1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, 100 mM sodium ortovanadate, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate in PBS) in the presence of protease inhibitors (4 mg/mL of leupeptin, aprotinin, pepstatin A, chymostatin, PMSF and 5 mg/mL of TPCK). The homogenates were sonicated twice by three strokes (20 Hz for 20 s each); after centrifugation for 30 min at 10,000 g, the supernatants were stored at 80 °C. Proteins (40 μg) were separated by 9% SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond-P polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK) at 280 mA for 2.5 h at 4 °C. The filters were treated for 3 h with blocking solution [5% skim milk in TBS (10 mM Tris–Hcl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl)] containing 0.25% Tween-20 (Sigma–Aldrich Corp., Milan, Italy) before the addition of anti-DAAM1 (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy), or anti-ACTIN (Elabscience Biotechnology, Wuhan, China) antibodies diluted respectively 1:3000 and 1:5000, incubated overnight at 4 °C. After three washes in TBST (TBS including 0.25% Tween20), the filters were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) for the rabbit anti-DAAM1 antibody diluted 1:10,000 in the blocking solution, or anti-mouse IgG (ImmunoReagents, Inc., Raleigh, NC, USA) for the mouse anti-actin diluted 1:10,000 in the same blocking solution. Then, the filters were washed again three times in TBST and the immunocomplexes were revealed using the ECL-Western blotting detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK).

2.4 Histological analysis

In order to assess the quality and to characterize the histology of the tissue samples, 7-μm-thick mouse seminal vesicles sections were obtained, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined under a light microscope (Leica DM 2500) for histological evaluation. Photographs were taken using the Leica DFC320 R2 digital camera.

2.5 Immunofluorescence analysis

For the co-localization experiments for DAAM1 + ACTIN, 7 μm-seminal vesicles sections were dewaxed, rehydrated and processed as described by Pariante et al. [23]. Briefly, antigen retrieval was performed by pressure-cooking slides for 3 min in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with an appropriate normal serum diluted 1:5 in PBS containing 5% (w/v) BSA before the addition of anti-DAAM1, or anti-ACTIN antibodies diluted 1:100, for overnight incubation at 4 °C. After washing in PBS, the slides were incubated for 1 h with the appropriate secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, Invitrogen; FITC-Jackson, ImmunoResearch, Pero MI, Italy; Anti-Mouse IgG 568, Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) diluted 1:500 in the blocking mixture. The slides were mounted with Vectashield + DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Peterborought, UK) for nuclear staining, and then observed under the optical microscope (Leica DM 5000 B + CTR 5000) and images were viewed and saved with IM 1000.

3 Results

3.1 DAAM1 transcript and proteins in adult mouse seminal vesicles

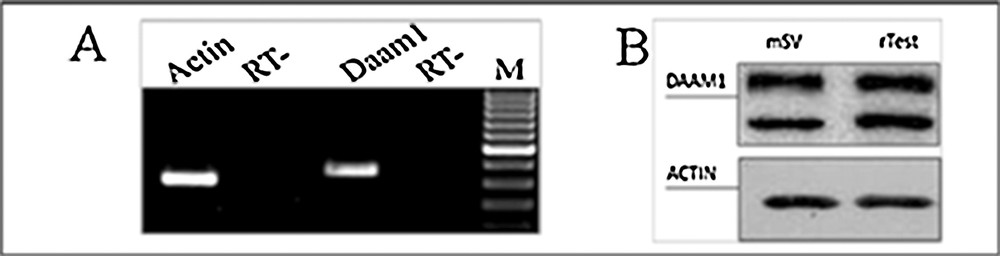

The presence of Daam1 mRNA was first investigated in adult mouse seminal vesicles by semiquantitative relative RT-PCR analysis. Agarose gel electrophoresis of amplification products showed a single band of the expected size (392 bp for Daam1) in cDNA from seminal vesicles (Fig. 1A). The amplified cDNA band corresponded to the Damm1 transcript, as demonstrated by the successive cloning and sequencing (not shown). The quality control of cDNA was performed using specific primers for Actin mRNA (Fig. 1A). The PCR analysis on negative control (RT−) samples did not show any signal. The expression of DAAM1 was also evidenced by Western blot analysis using polyclonal anti-DAAM1 antibody: a 123-kDa band (corresponding to DAAM1) was present in total extracts from adult mouse seminal vesicles and rat testis, used as a control. Another, lower band was detected, probably due to post-translational modifications (Fig. 1B). The same samples were employed for the analysis of ACTIN. As expected, its band was detected in both samples, as a confirmation of the expression of the protein in mouse seminal vesicles and rat testis (Fig. 1B).

Expression of DAAM1 mRNA and protein in adult mouse seminal vesicles. A. Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products performed on total RNA from adult mouse seminal vesicles. The amplification products were obtained using specific primers for mouse Daam1 and Actin and mRNA. M: molecular weight marker XIV (Roche Diagnostics); RT−: negative control. B. Western blot analysis for DAAM1(123 kDa, top section) and ACTIN (42 kDa, bottom section) performed on total protein extracts from adult mouse seminal vesicles (mSV) and rat testis (rTest), used as a positive control (Pariante et al., 2016).

3.2 Co-localization of DAAM1 + ACTIN in mouse seminal vesicles

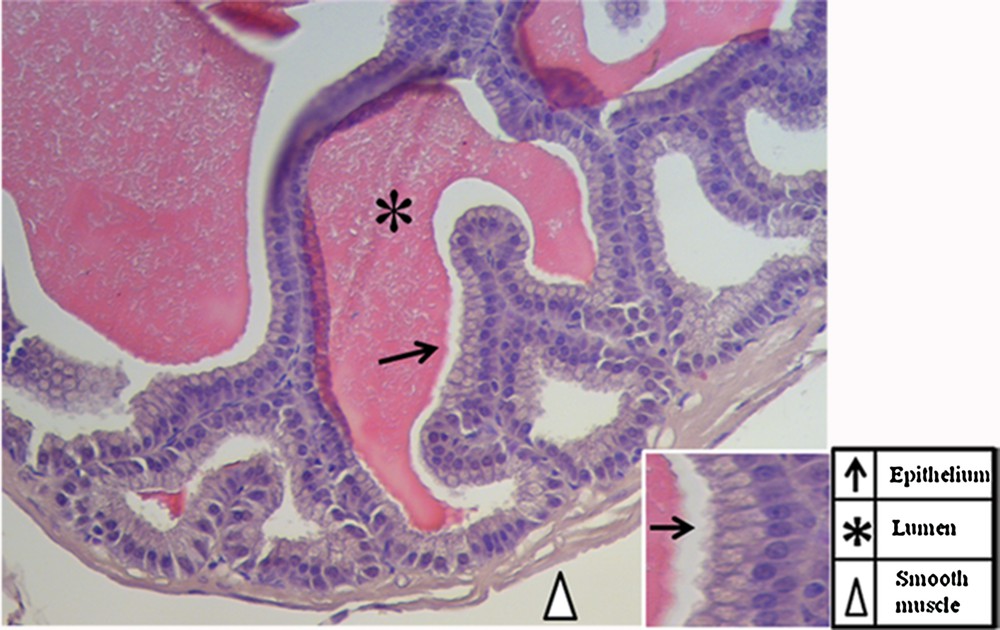

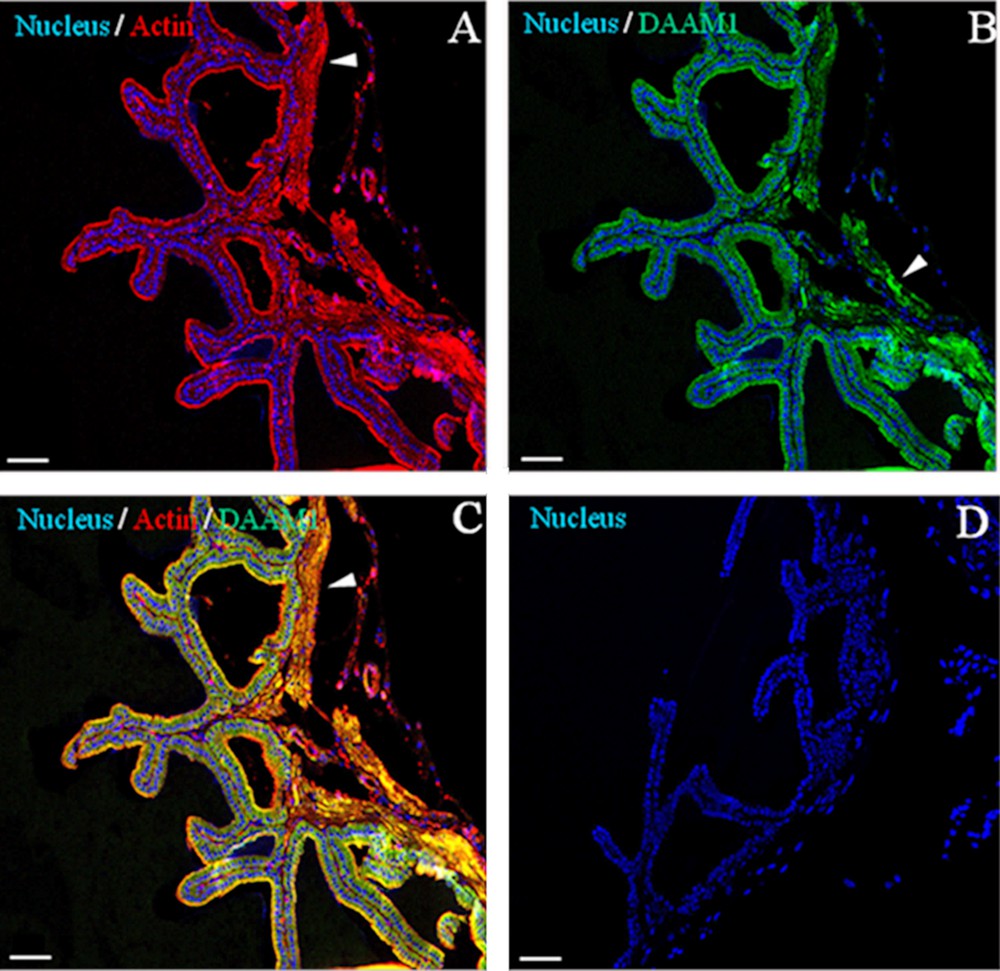

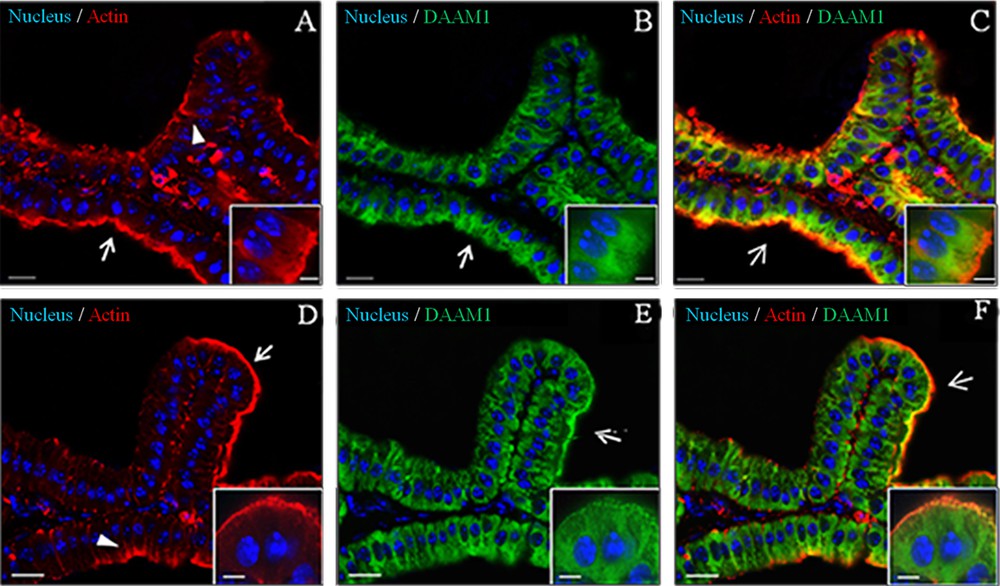

First, in order to check tissue quality and to distinguish the morphology of the tissue, a haematoxylin-eosin staining was performed on seminal vesicles sections (Fig. 2). The seminal vesicle is lined by a pseudostratified epithelium with columnar secretory cells (arrows) and smaller basal cells. The epithelium is highly folded and deep narrow crypts lined with epithelium extend from the main sac-like lumen (asterisk). A lamina propria of connective tissue and thick coat of smooth muscle surround the epithelial lining (arrowhead). The nucleus of each columnar cell is located in the basal portion and is elongated in the direction of the long axis of the cell [32]. Then, to obtain detailed data on DAAM1distribution inside the seminal vesicles, a co-localization experiment of DAAM1 + ACTIN was studied by immunofluorescence analysis (Figs. 3–4). We showed that a positive signal for the two proteins was found in the cells of smooth muscles that surround the epithelium (arrowheads, Fig. 3). Moreover, both proteins showed a cytoplasmic localization inside the epithelial cells, but with slight differences in their expression pattern: ACTIN is evident at cell-cell junctions (arrowheads, Fig. 4A, D; better highlighted in the inset) and at cell cortex (arrows, Fig. 4A, D; better highlighted in the inset); DAAM1 had a more diffused localization, but is also prominent at the apical membrane (Fig. 4B, E better highlighted in the inset). Fig. 4C and F show that DAAM1 signal noticeably overlaps with the fluorescence produced by ACTIN (see arrows and arrowheads), confirming their association at the apical plasmatic membrane, where the two co-localization signals produce the intermediate yellow–orange tint.

Haematoxylin-eosin staining of a tissue section in which the normal histology of the adult mouse seminal vesicles is highlighted (A). The scale bars represent 20 μm in (A) and 5 μm in the inset. The pointer legend is provided in the bottom-right table.

Immunolocalization of DAAM1 in adult mouse seminal vesicles. General appearance of DAAM1 (green, B and C) co-localization by double IF with ACTIN (red, A and C) on mouse seminal vesicles sections. The data show that DAAM1 co-localizes with ACTIN in the muscular cells (arrowheads). The nucleus is marked in blue (A–D). D. Negative control, obtained by omitting the primary antibodies. The scale bars represent 40 mm.

Co-localization of DAAM1 and ACTIN in adult mouse seminal vesicles. Two different fields were captured [field 1: (A/C); field 2: (D/F)]. A, D. DAPI-fluorescent nuclear staining (blue) and ACTIN staining (red). ACTIN localizes both at cell–cell junctions (arrowheads) and at the apical plasmatic membrane (arrows). B, E. DAPI-fluorescent nuclear staining (blue) and DAAM1 staining (green). DAAM1 is prominent at the apical membrane (arrows). C, F. Merged fluorescent channels (blue/red/green), which enhances the co-localization of DAAM1 and ACTIN at the apical plasmatic membrane (arrows). The scale bars represent 20 μm, except for the insets, where they represent 10 μm.

4 Discussion

The seminal vesicles (SV), together with the prostate and Cowper's gland, constitute the male sex accessory glands. These glands are present in most families of placental mammals [25] where their secretions can reach more than 60–70% of the seminal plasma [27]. SV secretions are mixed with spermatozoa and secretions from other accessory reproductive glands before being ejaculated into the vagina. The contribution of seminal vesicles to the seminal plasma includes ions (e.g., Na+, K+, Zn+), sugars (e.g., fructose, glucose), peptides (e.g., glutathione) and, above all, highly concentrated proteins. The relevance of SV for fertility is related to the influence of their secretions on sperm motility, metabolism and surface components [33–36] and to their role in the immunology of reproductive functions [36–39]. Once synthesized, these components are released in the lumen of the gland, where they contribute to form the ejaculate. The secretion is regulated by testosterone [26], and during exocytosis, the secretory vesicles are delivered to the cell periphery, where they reside until the hormonal stimulus starts their fusion with the plasma membrane. The molecular pathway controlling regulated exocytosis has been extensively investigated. In fact, several factors have been identified as key regulators in the process, such as intracellular Ca2+ levels, ion channels, G proteins-coupled receptors, small GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton [40–45]. In particular, actin cytoskeleton remodelling plays a crucial role during regulated exocytosis, including membrane budding, fusion and fission [46–48]. Moreover, it has been proposed a dual action of actin filaments during these processes. Actin can negatively regulate exocytosis, creating a sort of barrier beneath the plasma membrane, preventing its fusion with secretory vesicles; on the other hand, together with actin-based motors, this protein can facilitate the transport of the vesicles toward the fusion site. This double behavior suggests that regulated exocytosis requires a fine control of assembly and disassembly of actin filaments [49,50]. Today, it is known that part of actin regulation is performed by Wnt proteins [51]. Upon interaction with the membrane frizzled/co-receptor complex [52], Wnt recruits Dishevelled (Dvl), which can activate different pathways. In planar-cell polarity (PCP) non-canonical pathway, Dvl can activate the formin DAAM1, interacting with its DAD (DAAM autoinhibitory domain) region. The Dvl/DAAM1 complex is, then, able to recruit and activate, through the formin homology (FH) 1 domain, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor WGEF, which, in turn, activates a Rho GTPase [8,9,53]. The subsequent activation of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) [10] results in actin polymerization at the dimerized FH2 domain [54] and, consequently, in cytoskeletal reorganization. Given the involvement of both actin and small GTPases during exocytosis, and being DAAM1 itself a general regulator of actin nucleation, the major aim of the present study was to investigate the possible association of DAAM1 and actin in the SV epithelium. The firsts evidences come from the PCR and Western blot expression data: DAAM1 is, indeed, expressed in the adult SV. The successive localization analysis highlighted that the protein localizes to the cytoplasm of epithelial cells. It is also possible to note congruence between DAAM1 profile and actin distribution, and in particular at the cell cortex. This is very interesting: it has been reported that another protein belonging to the formin family, mDia, co-localizes with actin at the apical surface of the exocrine pancreas cells, regulating the formation of actin bundles [29,30]. This information, coupled with our result, may suggest a possible involvement of DAAM1 during exocytosis, as the protein has an analogue activity as mDia. In fact, upon stimulation, sequential events take place, including an initial actin depolymerization, which frees the secretory vesicles and let them reach the plasma membrane, followed by a rapid polymerization [55,56]. This regulation requires the coordinate activity of the two GTPases: RhoA and cdc42 [57,58]. In particular, the first one is activated to restore the actin bundles beneath the plasma membrane. In this scenario, DAAM1, regulating RhoA activity, could participate in the polymerization events that occur after the release of the secretory vesicles. Finally, it is interesting to note that smooth muscular cells are immunopositive for DAAM1 and that they are associated with actin. Smooth muscle cells are major constituents of the walls of blood vessels and visceral organs (apart from the heart) and are responsible for dynamic changes in the diameter and volume of these organs. Also in this case, formins and small GTPases of the Rho family play a crucial role in actin cytoskeleton remodelling and actomyosin-based contractility [59,60]. Being formin DAAM1 itself a positive regulator of RhoA, it is possible to assert that DAAM1 can be involved in the dynamic rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton in the contractile machinery of smooth muscle. In conclusion, our work shows, for the first time, the expression and the localization of DAAM1 in adult mouse SV. Though further investigation is required to better understand the possible implications of such varied pattern, our current data provide a profile of DAAM1 co-localization with actin, suggesting its possible involvement as an actor in morpho functional remodelling and organization of the epithelium and smooth muscle of these exocrine glands.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”.