1 Introduction

Invasive ants, which are among the most harmful bioinvaders known, penetrate ecosystems by eliminating native ants; then, they directly or indirectly affect all other organisms, disrupting native communities [1]. Among them, fire ants belong to the Solenopsis genus (Myrmicinae: Solenopsidini) that refers to a Neotropical species assemblage of the Solenopsis saevissima species-group including, among others, Solenopsis geminata (Fabricius), Solenopsis invicta Buren, Solenopsis richteri Forel and S. saevissima (Smith). S. geminata, has been spread pan-tropically through human activity, invading open areas [1]. S. invicta and S. richteri, which can hybridise, were accidentally imported into the southern United States from northern Argentina [2]. S. richteri is confined to Mississippi and northern Alabama, while S. invicta has now colonized 15 states in the continental USA, Puerto Rico, and parts of Australia and Asia [1,3].

A survey based on mitochondrial DNA sequences proved the monophyly of the S. saevissima species-group, consistent with a single Neotropical origin and radiation of this group of ants [4]. More recently, it was demonstrated that S. richteri, S. invicta and S. saevissima show a strong regional genetic differentiation within their native ranges, corresponding to long-term lineage independence. In fact, the occurrence of morphologically cryptic species has been shown in ‘nominal’ S. invicta and in S. saevissima [5,6]. It has been proposed that S. saevissima populations from the southern highlands, southeastern Atlantic, and central Atlantic regions of Brazil constitute new, undescribed species; S. saevissima sensu stricto extends over a very wide area of southwestern, northwestern and Amazonian parts of Brazil [6].

This study focuses on S. saevissima, a species that has been little studied although it is considered to be a major pest ant in human-disturbed areas in its native range, which is located between southern Brazil and Suriname and suspected to have the potential to become invasive [3,6–8]. Indeed, it shares some lineages with S. invicta, S. richteri and even S. geminata [6]. Also, S. saevissima and S. invicta workers are morphologically very similar, their colonies are difficult to distinguish and their sting is similarly potent [3,8]. Like invasive ants, S. saevissima is omnivorous, actively recruits nestmates to large food sources and displaces other ants [3,7,8]. Its colonies have been considered to be monodomous and monogynous (one nest and one queen per colony) [7]; yet, we noted that each mound is connected to the surrounding mounds through a network of galleries. The workers first dig a trench between two nests; as they dig deeper and deeper, the upper edges close over the top of the trench, forming a gallery. Subterranean foraging trails radiating out from the nest, permitting foragers to travel less than 0.5 m above ground to gather food, were noted for S. invicta and S. richteri and considered to reduce the hazard of attacks by parasitoids [9,10], but not to interconnect the mounds.

Using confrontation tests, we examine to what extent these interconnections have spread in human-disturbed areas of French Guiana.

2 Materials and methods

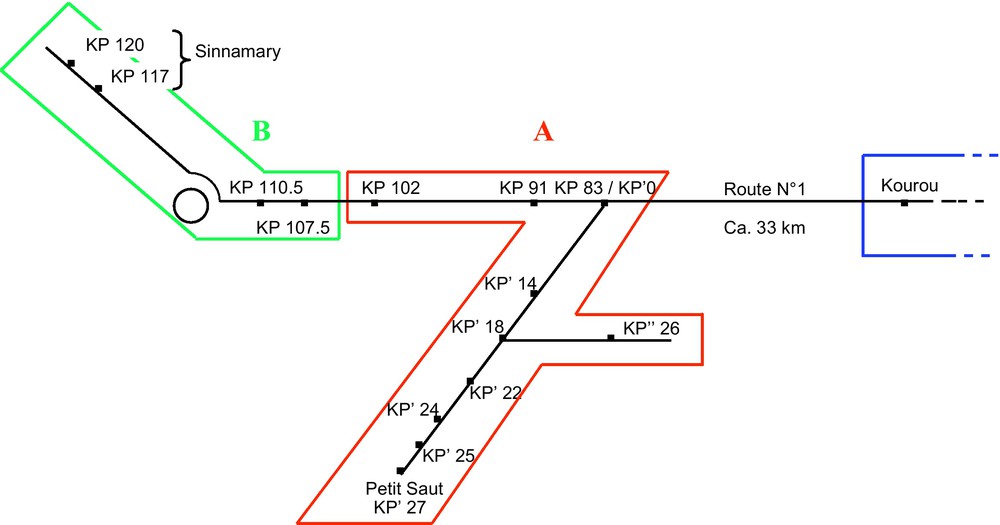

This study was conducted in French Guiana where S. saevissima is frequent in human-disturbed areas [11]. The study sites ranged from the Petit Saut dam to Sinnamary and Kourou, two cities connected by Route No. 1 (RN1) (Fig. 1). We collected S. saevissima workers from mounds situated at 15 different sites (Fig. 1). Workers from Kourou served as a reference. The 14 other sites were situated along the road between Petit Saut and Sinnamary (64 km in total; Fig. 1), each indexed according to its corresponding kilometric point (KP) on the road.

Map showing the distribution of S. saevissima nests from which we gathered workers for confrontation tests. Workers from Kourou served as a reference. The two other colonial groups are shown. All confrontations involving workers from Kourou resulted in a high level of aggressiveness (P < 0.01 when compared to confrontations between workers from the same nest). The same was true during confrontations involving workers from the two different colonial groups, while the confrontations between workers from each of the two colonial groups did not result in aggressiveness (P > 0.05 when compared to encounters between workers gathered from the same nest).

We used a shovel to recuperate the upper parts of the mounds composed of freshly turned-over earth and containing several hundred workers. Then, we put everything into plastic basins whose walls were coated with Fluon® to prevent the workers from climbing out. These basins were transported to the laboratory where we placed a Petri dish containing a piece of humid cotton and drops of honey into each basin, while the workers rearranged the earth, digging cavities and galleries. Interaction bioassays were conducted less than 24 h later.

We employed the standard behavioural tests commonly used in such studies [12,13] to test the level of antagonism between the S. saevissima individuals collected from the different sites. Indeed, many behavioural experiments have suggested that aggressiveness towards non-nestmates is induced by the chemosensory detection of differences in the cuticle-associated lipids of which hydrocarbons are the dominant constituents, although volatiles also play a role [14,15]. For the tests, two individual workers were placed into a neutral arena (Ø: 6 cm; height: 2 cm) whose walls were coated with fluon® to prevent the ants from climbing out. We scored the interactions between the workers over a 5-minute period on a scale from 1 to 4 (1: physical contact, but no aggressive response [may include antennation or trophallaxis]; 2: aggressiveness [biting for less than 3 s]; 3: attack [a physical attack by one or both of the workers, including biting for more than 3 s]; and 4: fighting [prolonged aggressiveness, including prolonged biting and the use of the sting by one or both ants]). We repeated the confrontations 15 times, retaining the highest value noted each time, and used each worker only once. The experiment, for which there were a total of 1575 confrontations involving workers from the 15 different sites, was conducted twice: at the end of the dry season in 2007 and mid-2008 during the rainy season. Because the results were identical, we present only one data set.

Levels of aggressiveness between colony pairs were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. A post hoc test (Dunn's test) was then conducted to isolate the groups that differed from the others. All of the statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 4.03, Inc. software.

3 Results and discussion

In no case did the confrontations between two S. saevissima workers gathered from the same nest result in aggressive behaviour as only a “level 1 behaviour” (i.e. antennations and trophallaxis) was noted. These interactions were then used as a reference for the other cases.

We noted a high level of aggressiveness during all of the confrontations involving workers from Kourou and ants from all of the 14 other sites (P < 0.01 when compared to encounters between nestmates).

On the contrary, the interactions did not result in aggressiveness during the confrontations between workers from each of two groups of nests (see below) as we noted mostly “level 1 behaviour” and very rarely “level 2 behaviour” (P > 0.05 when compared to encounters between workers gathered from the same nest). The first group is composed of nests from 10 sites situated along 54 km of road from Petit Saut to KP 102 on RN1 (Fig. 1A). The second group includes nests from four sites situated along 12.5 km of road from KP 107.5 to the city of Sinnamary (KP 120) (Fig. 1B). We again noted a high level of aggressiveness during confrontations between workers gathered from the nests belonging to the two different colonial groups described above. Biting and stinging were frequently observed during these confrontations, but generally, one worker then escaped or avoided the other after the first aggressive encounter. Gaster flagging, already described in S. invicta as the airborne dispersal of venom during a heterospecific encounter [16], was frequent; while reciprocal full attacks were rare.

The present study has shown that in human-disturbed areas in its native range S. saevissima can form large colonial groups with workers tolerating each other in the same way that they tolerate nestmates gathered from the same nest. Similar ecological patterns have also been noted in invasive, unicolonial ant species, so that it is thought that their ability to adapt to disturbances within their native habitats might be a key factor in their invasive success [17]. The interconnection of S. saevissima nests over a wide range implies that, even if each mound contains only one queen [7], the colonial groups are both polygynous (multiple queens) and polydomous (multiple nests), two traits that can favour the expansion of “colonies” [1]. Note that monogyny or polygyny can occur in S. invicta and S. richteri [18]. In both cases, colonies of the monogynous form defend foraging territories, so that their nests are relatively uniformly spaced, while workers from polygynous colonies may show little aggressiveness toward conspecific, alien workers and do not defend territories [19,20].

The large size of the colonial groups enhances the threat occasioned by S. saevissima for both agriculture and the environment [3,8] because it makes this species difficult to control. Indeed, roads serve as interconnections between human-disturbed areas over which the colonial groups can spread, so that eliminating only some of the nests is futile as this species can very rapidly re-occupy these sites.

The ‘nominal’ S. saevissima includes several morphologically cryptic species. Yet, the distribution of what is now considered to be S. saevissima sensu stricto is very wide, extending from southwestern to northwestern Brazil and to the Amazon basin [6]. It is therefore likely that the Guianese population belongs to this group. The fact that S. saevissima colonial entities can extend over wide areas (this study) is alarming because this species likely has the ability to become invasive if imported into wet tropical countries [8]. Indeed, it shares biological and ecological characteristics with the invasive species S. invicta and S. richteri with which it can hybridise [3,6–8].

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andrea Dejean for proofreading the manuscript, and to Pierre Uzac, David Oudjani and Mikaël Negrini for their help during field work and data processing. Financial support for this study was provided by the Programme Amazonie II of the French Centre national de la recherche scientifique (Project 2ID) and the Programme Convergence 2007–2013, Région Guyane, from the European community (Project DEGA).