1 Introduction

Oxaziridines are a class of three-membered heterocycles, which have received attention as potential anti-tumour agents [1,2], and analogues of penicillin [3,4]. Furthermore, they are widely used as reagents and intermediates in the preparation of biologically active molecules [5–7].

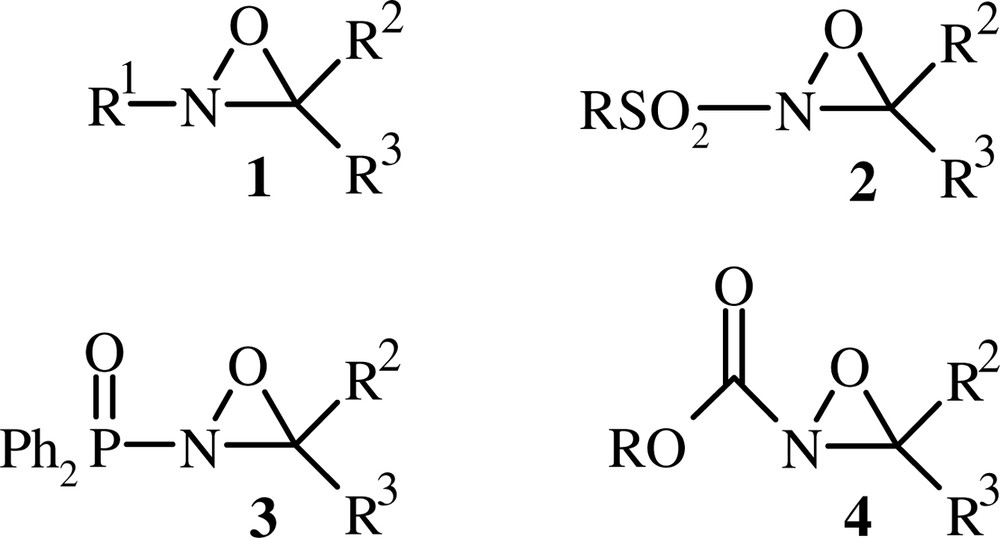

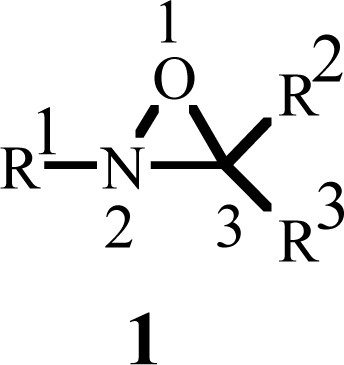

The reactivity of oxaziridines depends generally on the nature of the substituent linked to the N-atom of the cycle (Fig. 1). Indeed, N-alkyloxaziridines 1 undergo a number of addition and cycloaddition reactions with heterocumulenes [8,9]. N-Sulfonyloxaziridines [5] 2 and N-phosphinoyloxaziridines [10] 3 react as oxygenating reagents with nucleophiles, and N-alkoxycarbonyloxaziridines 4 are used as electrophilic aminating agents [11]. In addition to these properties, oxaziridines show a remarkable configurational stability about nitrogen. Indeed, (E) and (Z) oxaziridine isomers were separated and characterised in many instances [12–14].

Oxaziridines 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Oxaziridines are available by several synthetic methods. The photoisomerization of nitrones [15], the electrophilic amination of carbonyl compounds [16] and the oxidation of imines with several oxidizing agents such as buffered oxone® [8], UHP/maleic anhydride system [17], molecular oxygen in the presence of transition-metal complexes [18] and a nitrile/hydrogen peroxide system [19] have been used for this purpose. Until now, the sole general method, able to lead to oxaziridines 1, 2 and 3, is the oxidation of an imine with a peracid such as m-chloroperbenzoic acid 5 (MCPBA) [8,14,20] (Fig. 2).

Compounds 5 and 6.

We have previously reported [21] on the oxidation of prochiral and chiral N-arylidenealkylamines with the benzonitrile-hydrogen peroxide system in methanol at pH = 8, which afforded the corresponding 2-alkyl-3-aryloxaziridines with relatively good yields (60–90%). This inexpensive oxidant system provides the stereospecificity and the ease of preparation. However, it does not appear to be the best concurrent of MCPBA for the following reasons: (i) the oxidation of N-alkylimines with PhCN/H2O2 occurs within 48 h then, a long exposure of imines to aqueous media increases the rate of their decomposition; (ii) we have found that PhCN/H2O2 oxidation of imines is suitable for the synthesis of oxaziridines 1 rather than oxaziridines 2 and 3; (iii) the reaction occurs in alcoholic media rather than in other solvents. Therefore, our main focus was to find a highly reactive nitrile–hydrogen peroxide system to overcome the above limitations and to develop an oxidant system of imines that could compete with MCPBA at the level of cost and reactivity. For this purpose, we have selected the trichloroacetonitrile, which affords in situ the trichloromethylperoxyimidic acid 6 (Fig. 2) upon addition of aqueous H2O2 (30%) [22]. This oxidant reagent was found to be efficient for epoxidation of olefins.

In this report, we describe the synthesis of oxaziridines 1, 2 and 3 by oxidation of the corresponding imines with CCl3CN/H2O2 (30%), in basic media (Scheme 1). In addition, we examine the solvent’s effect on the stereoselectivity of the reaction. Two possible mechanisms for this reaction are discussed according to experimental evidences.

Synthesis of oxaziridines.

2 Results and discussion

The starting imines were prepared according to literature methods [14,20,23,24]. All aldimines were obtained as one geometrical isomer, presumably the thermodynamically favoured anti-imine [14,21,25,26]. We have found that the CCl3CN/H2O2 oxidation of N-alkylimines in CH2Cl2, in the presence of NaHCO3, furnished the corresponding oxaziridines in good to high yields (Table 1). Oxidation of N-tertiobutylimines led exclusively to the corresponding (E)-oxaziridines 1a–d (entries 1–4). The less stable (Z)-isomer could not be obtained because of the bulkiness of the substituents [14,21,25]. Unlike, the oxidation of N-arylideneisopropylamines 1e–h and N-arylidenecyclohexylamine 1j proceeded stereoselectively (entries 5–8, 10), producing the (E) oxaziridine isomer as a primary product (> 80% in all cases). Proportions of (Z) oxaziridines formed after oxidation of (anti)-imines with MCPBA are fairly larger than those formed by use of the peroxyimidic acid 6 (< 20% of (Z)-oxaziridines in all cases). For example, 15% of (Z)-3-(p-nitrophenyl)-2-isopropyloxaziridine was formed after oxidation of the corresponding (anti)-N-p-nitrobenzylideneisopropylamine with 6 in CH2Cl2 (entry 7), and 39% was obtained by the MCPBA process [25]. The 1H NMR spectra of crude products showed more than 98% conversion of N-arylidenealkylamines to the corresponding 2-alkyl-3-aryloxaziridines. In none of these cases were any by-products, such as N-oxide, formed. Only traces of aldehydes (< 2%), arisen from decomposition of imines, were detected in these spectra. Therefore, pure (E) and (Z) oxaziridines were obtained in good to excellent yields by flash column chromatography. Yet, the imine–peroxyacid synthesis of 2-alkyl-3-aryloxaziridines regenerates a significant amount of aldehyde (10–46%)[14,25]. Accordingly, the separation of (E) and (Z) oxaziridines often requires repeated column chromatography. Furthermore, N-oxides were also formed with oxaziridines when N-arylidenealkylamines with electron-donating aromatic substituents were oxidised by peracids in aprotic solvents [27].

Oxidation of imines with CCl3CN/H2O2 in CH2Cl2, in the presence of NaHCO3

| ||||||||

| Entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | Product | Time (h) | Conv. (%)a | Ratio E/Z (%)b | Isolated yields E/Z (%)c |

| 1 | tBu | H | Ph | 1a | 1 | > 98 | 100/0 | 93 |

| 2 | tBu | H | 4-MeO–C6H4 | 1b | 1 | > 98 | 100/0 | 89 |

| 3 | tBu | H | 4-NO2–C6H4 | 1c | 1 | > 98 | 100/0 | 92 |

| 4 | tBu | H | iPr | 1d | 2 | 79d | 100/0 | 67 |

| 5 | iPr | H | Ph | 1e | 1 | > 98 | 86/14 | 73/9 |

| 6 | iPr | H | 4-NO2–C6H4 | 1f | 1 | > 98 | 85/15 | 75/9 |

| 7 | iPr | H | 4-Br–C6H4 | 1g | 1 | > 98 | 85/15 | 76/6 |

| 8 | iPr | H | 3-Cl–C6H4 | 1h | 1 | > 98 | 81/19 | 70/10 |

| 9 | iPr | Ph | Ph | 1i | 2.5 | 87d | — | 77 |

| 10 | c-C6H11 | H | Ph | 1j | 1 | > 98 | 82/18 | 73/12 |

| 11 | c-C6H11 | H | Me | 1k | 2 | 75d,e | 100/0 | 63 |

a Estimated from 1H NMR spectra of crude oxaziridines.

b Determined by 1H NMR integration of H-3 signals (near 5.2 ppm for (Z) isomer and near 4.5 ppm for the (E)-isomer) [14,21,25].

c Isolated yields of (E) and (Z) oxaziridines, separated by flash chromatography.

d Determined by iodometric titration [21].

We have found that an excess of CCl3CN (2 equiv) and H2O2 (3 equiv) was necessary to ensure the complete consumption of the starting imine in a reasonably short time. On the other hand, NaHCO3 is used as a buffering agent rather than a basic catalyst. Indeed, rapid reaction occurred without use of NaHCO3. In this case, E/Z ratios of 2-alkyl-3-aryloxaziridines were quite similar, but yields were lowered by significant decomposition of imines, presumably, due to the acidity of the H2O2 aqueous solution (up to 12% of aromatic aldehydes were formed).

In this work, we have found that the reactivity of the trichloromethylperoxyimic acid 6 toward N-alkylimines is consistently higher than peroxyimidic acids derived from chloroacetonitrile, acetonitrile and benzonitrile (Table 2). Apparently, the enhanced reactivity of N-alkylimines with 6 is due to the electron-withdrawing trichloromethyl groups, which have the capacity to lower the energy of the σ* level of the O–O bond of 6 [22], and to facilitate the electrophilic oxygen transfer to N-alkylimines.

Oxidation of (anti)-PhCH=NtBu with R4CN/H2O2 at room temperature, in the presence of NaHCO3

| R4 | Solvent | Time (h) | Conv. (%) |

| Ph | MeOH | 48 | 90 |

| Me | MeOH | 30 | 91 |

| CH2Cl | MeOH | 20 | 98 |

| CH2Cl | CH2Cl2 | 20 | 96 |

| CCl3 | CH2Cl2 | 1 | > 98 |

The effect of solvent upon oxidation of N-arylidenealkylamines with the peroxyimidic acid 6 is summarised in Table 3. A better stereoselectivity, in favour to the (E)-oxaziridine isomer, was observed with alcoholic and ethereal solvents. On the other hand, non-polar solvents such as benzene and carbon tetrachloride proved to be inconvenient for this reaction.

Solvent effect on oxidation of (anti)-N-arylidenealkylamines (0.2 M) with CCl3CN (2 equiv)/H2O2 (3 equiv)

| Product | Solvent | Time (h) | Conv. (%)a | Ratio E/Z (%)b |

| 1f | CHCl3 | 1 | > 98 | 83/17 |

| 1f | CCl4 | 10 | 15 | — |

| 1f | C6H6 | 10 | trace | — |

| 1f | Et2O | 1 | > 98 | 93/7 |

| 1f | THF | 1 | > 98 | 93/7 |

| 1f | iPrOH | 1.5 | > 98 | 94/6 |

| 1f | MeOH | 1.5 | >98 | 94/6 |

| 1e | MeOH | 1.5 | >98 | 94/6 |

| 1g | MeOH | 1.5 | > 98 | 95/5 |

| 1h | MeOH | 1.5 | >98 | 97/3 |

| 1j | MeOH | 1.5 | > 98 | 94/6 |

a Estimated from 1H NMR spectra of crude oxaziridines.

b Determined by 1H NMR integration of the methine proton signals.

We extended the process to more functionalized imines, namely N-sulfonylimines and N-phosphinoylimines, which were subjected to reaction with CCl3CN/H2O2 in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C. We have found that the addition of a catalytic amount of tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB) as a phase transfer catalyst is required to afford N-sulfonyloxaziridines and N-phosphinoyloxaziridines in good to high yields (Table 4). Otherwise, no amounts of oxaziridines were detected after 3 h. We notice that only one oxaziridine isomer is produced by this reaction, namely, the thermodynamically favoured (E)-oxaziridine [20,28].

Oxidation of N-sulfonylimines and N-phosphinoylimines with CCl3CN/H2O2 in CH2Cl2, in the presence of TBAB and NaHCO3

| ||||

| R1 | X | Product | Time (h) | Isolated yield (%) |

| PhSO2 | H | 2a | 0.5 | 89 |

| Ts | H | 2b | 0.5 | 85 |

| MeSO2 | H | 2c | 0.5 | 76 |

| Ph2P(O) | H | 3a | 1 | 62 |

| Ph2P(O) | Cl | 3b | 1 | 54 |

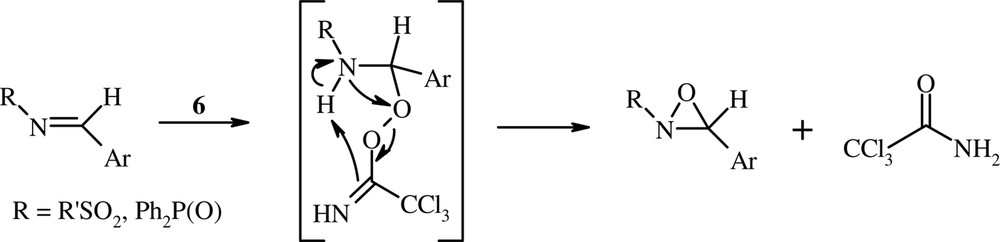

The mechanism of the peroxyacid-imine route to oxaziridines is generally considered a nucleophilic Baeyer–Villiger type of process (a two-step mechanism) rather than a concerted electrophilic oxygen transfer (type epoxidation of olefins) [25,28–30]. The oxidation of N-sulfonylimines and N-phosphinoylimines with the peroxyimidic acid 6 appears to be consistent with a nucleophilic Baeyer–Villiger mechanism type (Scheme 2). Indeed, the necessity for carrying out the oxidation of these imines under biphasic conditions, in the presence of a phase transfer catalyst (TBAB), suggests that the peroxyimidic acid anion (CCl3C(NH)OO–) is added to the electron-deficient C–N double bond.

The two-step mechanism.

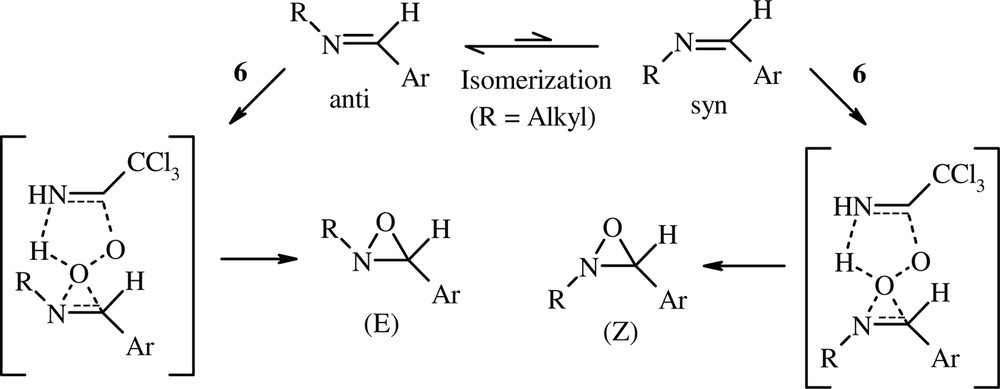

Nevertheless, this mechanism does not appear to be obvious for the oxidation of N-alkylimines with the peroxyimidic acid 6. Although oxidation of (anti)-N-arylidenealkylamines (except R1 = tBu) is not stereospecific, the concerted mechanism (type epoxidation) cannot be excluded, for the following reasons. (i) Isomerization of N-arylidenealkylamines is possible in the presence of trace amount of an acid [25,31]. Thus, the peroxyimidic acid 6 can incite the imine stereomutation. Consequently, (E) and (Z) oxaziridines may be formed from (anti)-imines according to a concerted mechanism (Scheme 3). (ii) The low reactivity of N-alkylimines toward nucleophiles is well-known [32]. It is improved by the presence of electron-withdrawing nitrogen substituents (RSO2 and Ph2P(O)). In this work, we have established that the use of TBAB (PTC) under biphasic conditions is required to convert the electrophilic electron-deficient N-sulfonylimines and N-phosphinoylimines into the corresponding oxaziridines. However, N-alkylimines showed high reactivity with 6 without use of TBAB. Apparently, these imines react with the peroxyimidic acid 6 rather than with the more nucleophilic peroxyimidate anion (CCl3C(NH)OO–). Thus, we think that the nucleophilic attack of N-alkylimines on the electrophilic oxygen of 6, analogous to epoxidation of alkenes, is possible. (iii) We have found that competition experiment reaction of CCl3CN (1 equiv)/H2O2 (2 equiv) with p-MeO–PhCH=NtBu and p-O2N–PhCH=NtBu (10-fold excess of each imine) in CH2Cl2 showed that the electron-rich methoxyphenylimine reacted at a rate 14 times higher than that of the nitrophenylimine. By analogy with the work of Paredes et al. [33], this result may support the concerted mechanism.

The concerted mechanism.

In our opinion, statements (i)–(iii) could suggest that the epoxidation type of mechanism (Scheme 3) presents more convincing evidence than the nucleophilic Baeyer–Villiger process type, when N-alkylimines were oxidised with 6.

3 Conclusion

We have successfully developed a facile and efficient synthesis of oxaziridines by oxidation of imines with the CCl3CN/H2O2 system under mild conditions. Both electron-rich and electron-deficient imines were rapidly converted into the corresponding oxaziridines in good to excellent yields. The only other general method described in the literature is the oxidation of imines with MCPBA. The CCl3CN/H2O2 system appears to be better than MCPBA on cost, stereoselectivity and yields of oxaziridines. We believe that this procedure provides a valuable addition to current methodologies. According to experimental evidences, the concerted mechanism appears to be more probable for oxidation of N-alkylimines with the peroxyimidic acid 6. Nevertheless, the Baeyer–Villiger process type may be suggested for the oxidation of the electron-deficient N-sulfonylimines and N-phosphinoylimines.

4 Experimental section

Solvents were purified by standard methods. Melting points were determined on a Büchi SMP-20 capillary apparatus and are uncorrected. TLC was carried out on Merck 60F-254 precoated silica gel plates (0.25 mm) and column chromatography was performed with Merck silica gel (70–230 mesh). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AC-300 spectrometer (1H at 300 MHz and 13C at 75 MHz) with CDCl3 as solvent and TMS as internal standard reference. Mass spectrometry analyses were performed using a Hewlett Packard 5897 and ions detected after chemical ionisation (CI) at 70 eV. CCl3CN and H2O2 solution (30%) were purchased from Acros. All starting imines were prepared according to the literature procedures [14,20,23,24]. In all cases, the crude imine was purified before use, except for N-phosphinoylimines, which were immediately subjected to the oxidation step without further purification [20]. All oxaziridines mentioned have previously been reported, with the exception of 1g and 1h. 1a-e [34], 1f [12], 1i [35], 1j [36], 1k [37], 2a [24], 2b,c [28], 3a,b [20].

4.1 N-Alkyloxaziridines 1a–k, N-sulfonyloxaziridines 2a–c and N-phosphinoyloxaziridines 3a,b: general procedure

To a stirred solution of imines (10 mmol), CCl3CN (20 mmol) and NaHCO3 (1 g) in CH2Cl2 (50 ml) at 0 °C, was added a solution of H2O2 (30%) (30 mmol) over a period of 5 min. The mixture was stirred at room temperature until the imine was consumed (TLC). Then, the mixture was washed with water (250 ml) and extracted with three 50 ml portions of CH2Cl2. The combined organic phases were dried (MgSO4) and concentrated under reduced pressure (T < 30 °C). The concentrate was chromatographed on silica gel to afford pure (E) and (Z) oxaziridines. The synthesis of N-sulfonyloxaziridines and N-phosphinoyloxaziridines was carried out at 0 °C, in the presence of 1 mmol (0.1 equiv) of tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB). N-Alkyloxaziridines 1a–d, i, k (eluent: cyclohexane–EtOAc, 90:10). N-Alkyloxaziridines 1e–h,j (eluent: cyclohexane–EtOAc, 97:3). Oxaziridines 2a–c (eluent: cyclohexane–EtOAc, 95:5). Oxaziridines 3a,b (eluent: cyclohexane–chloroform, 50:50). The NMR 13C data of oxaziridines 1d,i,k and 2a–c were not reported in the literature.

4.2 3-Isopropyl-2-tertiobutyloxaziridine: 1d

Oil, bp 62 °C (0.5 mbar). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 0.94 (d, 3H, J = 6.9 Hz, iPr), 0.97 (d, 3H, J = 6.9 Hz, iPr), 1.04 (s, 9H, tBu), 1.49 (oct, 1H, J = 6.9 Hz, iPr), 3.56 (d, 1H, J = 6.9 Hz, CH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 17.15, 17.24, 25.21, 31.12, 57.31, 79.96.

4.3 3-(4-Bromophenyl)-2-isopropyloxaziridine: 1g

(E)-Isomer: Oil, bp 73 °C (0.004 mbar). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.16 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz, iPr), 1.31 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz, iPr), 2.34 (h, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz, iPr), 4.46 (s, 1H, CH), 7.29 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz, Ar), 7.50 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.93, 21.27, 62.63, 79.38, 124.21, 129.19, 131.74, 134.27. MS DCI/NH3: 260 (M + NH4+), 243 (M + H+).

(Z)-Isomer: oil. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 0.74 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz, iPr), 1.24 (d, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz, iPr), 2.28, h, 1H, J = 6.6 Hz, iPr), 5.23 (s, 1H, CH), 7.33 (d, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz, Ar), 7.56 (d, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.05, 21.65, 52.08, 79.39, 129.60, 129.63, 131.47, 131.51. MS DCI/NH3: 260 (M + NH4+), 243 (M + H+).

4.4 3-(3-Chlorophenyl)-2-isopropyloxaziridine: 1h

(E)-Isomer: oil, bp 52 °C (0.003 mbar). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.10 (d, 3H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 1.24 (d, 3H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 2.27 (h, 1H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 4.35 (s, 1H, CH), 7.18–7.33 (m, 4H, Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 19.26, 21.30, 63.00, 79.54, 126.10, 127.92, 130.17, 130.50, 135.01, 137.61. MS DCI/NH3: 215 (M + NH4+), 198 (M + H+).

(Z)-Isomer: Mp 58–59 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 0.77 (d, 3H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 1.25 (d, 3H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 2.29 (h, 1H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 5.23 (s, 1H, CH), 7.34–7.43 (m, 4H, Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.40, 22.02, 52.58, 79.59, 126.55, 128.39, 129.93, 130.07, 134.42, 134.76. MS DCI/NH3: 215 (M + NH4+), 198 (M + H+).

4.5 3,3-Diphenyl-2-isopropyloxaziridine: 1i

Mp 44–45 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 0.97 (d, 3H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 1.28 (d, 3H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 2.27 (h, 1H, J = 6.3 Hz, iPr), 7.32–7.52 (m, 10H, Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.44, 21.67, 53.44, 86.62, 127.92, 128.19, 128.93, 128.97, 129.04, 134.58, 139.59.

4.6 2-Cyclohexyl-3-methyloxaziridine: 1k

Oil, bp 45 °C (1.5 mbar). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.23 (d, 3H, J = 4.5 Hz, Me), 1.30–1.78 (m, 10H, cyclohexyl), 1.90 (m, 1H, cyclohexyl), 3.74 (quad, 1H, J = 4.5 Hz, CH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 18.71, 23.95, 24.44, 25.72, 29.10, 31.51, 69.35, 77.62.

4.7 2-Phenylsulfonyl-3-phenyloxaziridine: 2a

Mp 92–94 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 5.48 (s, 1H, CH), 7.45 (m, 5H, Ar), 7.58–7.78 (m, 3H, Ar), 8.04 (br d, 2H, J = 7.0 Hz, Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 76.38, 128.31, 128.82, 129.42, 129.48, 131.54, 135.14.

4.8 2-(4-Methylphenylsulfonyl)-3-phenyloxaziridine: 2b

Mp 86–88 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.47 (s, 3H, Me), 5.44 (s, 1H, CH), 7.38–7.44 (m, 7H, Ar), 7.92 (d, 2H, J = 8.3 Hz, Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 21.89, 76.42, 128.30, 128.80, 129.48, 130.12, 130.61, 131.46, 131.53, 146.51.

4.9 2-Methylsulfonyl-3-phenyloxaziridine: 2c

Mp 60–61 °C. 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 3.22 (s, 1H, Me), 5.45 (s, 1H, CH), 7.43–7.50 (m, 5H, Ar). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 38.25, 75.32, 128.27, 128.82, 130.19, 131.56.

4.10 Competition experiment reaction of the peroxyimidic acid with imines

To a stirred solution of p-methoxybenzylidenetertiobutylamine (1 mmol), p-nitrobenzylidenetertiobutylamine (1 mmol) and trichloroacetonitrile (0.1 mmol) in 10 ml of CH2Cl2 was added a solution of H2O2 (30%) (0.2 mmol). The solution was allowed to stir for 1 h at 0 °C, then it was washed with 50 ml of water and extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was separated, dried (MgSO4) and concentrated under reduced pressure. The concentrate was analysed by 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3). Integration gave 0.07 for the nitrophenyloxaziridine 1c (4.75 ppm, 1H, CH) and 1.00 for the methoxyphenyloxaziridine 1b (4.61 ppm, 1H, CH and 3.79 ppm, 3H, OMe). This translates to 92.5% for 1b and 6.5% for 1c.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank the ‘Direction générale de la Recherche scientifique et de la Rénovation technologique’ and the ‘Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur’ (Tunisia) for their generous support of our program.