1 Introduction

1.1 Potential of phenolics of mustard and rapeseed

Food manufacturers use food-grade commercial antioxidants to prevent deterioration of products and to maintain their nutritional value. Antioxidants have also drawn attention from biochemists and health professionals for their beneficial health aspects. The use of extracts with antioxidative compounds from plant extracts instead of commercial antioxidants like BHT and BHA has been discussed in the recent years. The current project focuses on the extraction of antioxidants from the by-product of rapeseed (canola) oil processing using an optimized method. These by-products of oil processing are normally referred to as meals. Meals (press cakes) contain after the extraction of oil large amounts of phenolic compounds. The phenolic compounds contribute to the dark colour, bitter taste and astringency of rapeseed or mustard meals. They may also interact with amino acids, enzymes and other food components, thus influencing the nutritional significance of the meal [1–3]. On the other hand, the phenolic compounds can be extracted using pure or aqueous solvents like methanol and ethanol etc. and utilized as natural antioxidants. The meals have a significant phenol content, which implies their antioxidative power. Sinapic acid (Fig. 1), the main phenolic compound of rapeseed constitutes over 73% of free phenolic acids and about 80–99% of the main phenolic acids mainly occurring as esters and glucosides. Sinapin (Fig. 2), the cholin ester of sinapic acid is the main phenolic ester in rapeseed. The most active antioxidative component of canola meal and the polar fraction of rapeseed oil were identified as 1-o-β-d-glucopyranosyl sinapate (C17H22O10), a sinapic acid derivative [4] and vinylsyringol (C10H12O3), a decarboxylation product of sinapic acid [5]. Sinapic acid has been demonstrated to be a potent radical scavenger and to be a potent antioxidant in several lipid-containing systems [6]. In addition, sinapic acid is known to have peroxynitrite (ONOO–)-scavenging activity and can be utilized for protection of cellular defence activity against ONOO– involved diseases [7]. Other prospects for use of the meal include extraction of proteins fit for human consumption, since the meal contains normally around 50% protein content [8]. Industrial use of rape meal includes use as fuel/ bio diesel, fertilizers and animal feeds. Sinapin is responsible for fishy odours in brown-shelled eggs when incorporated in poultry rations. At dietary levels higher than 5%, rapeseed meal may result in enlarged thyroids, kidneys and livers in starting and growing swine. Therefore, aspects of processing technology, flavour, colour, anti-nutritional factor and functionality of meal and meal products remain to be investigated in a broader sense.

Sinapic acid.

Sinapin.

1.2 Application of phenolic ingredients in rapeseed oil

Rapeseed oil is subjected to high temperatures during extraction and processing which removes many phenolics including sinapic acid derivatives. The amounts of phenolics were found to be greatest in the post-expelled crude rapeseed oil, decreasing with an increasing degree of refining [5]. However, cold-pressed rapeseed oil has been shown to be more susceptible to oxidation than refined rapeseed oil. The lower stability of cold-pressed rapeseed is attributed to the higher degree of oxidation prior to the incubation experiment. In order to maintain a high content of phenolic compounds in the oil after the refining process, phenols extracted from the rapeseed meal can be added after the refining process to the oil resulting in a value added rape oil. Food manufacturers use food-grade commercial antioxidants to prevent quality deterioration and to maintain the nutritional value of different food products including oils and products containing oil. The interest in the use of extracts with antioxidative compounds from plant extracts instead of commercial antioxidants like BHT and BHA has been increased in recent years.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Commercial rape meals were procured from four different industries (situated in different parts of Germany) and two different mustard meal samples for the study were taken from India. Refined rape oil for stripping was purchased from a German rape oil company. Folin–Ciocalteau phenol reagent was supplied by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). All antioxidants including sinapic acid were either from Sigma or Merck. All solvents used were of analytical grade.

2.2 Extraction of antioxidative compounds from rape meal

Meal (1 g, oil-free press cake) was extracted three times with 9 ml extraction solvent (e.g., 70% methanol, i.e., methanol/water 7:3) using ultrasounds followed by centrifugation under refrigerated conditions (10 min at 5000 g) and filtration. The extract was made up to a total volume of 25 ml. Meal extracts have been classified into free phenolics, released from esterified phenolics and insoluble bound phenolics according to the method of Krygier et al. [9].

2.3 Content of phenolic compounds

Aliquots (0.1 ml) of extracts were diluted (1:5) with water and Folin–Ciocalteau phenol reagent (0.5 ml) was added. After 3 min, 19% sodium carbonate (1 ml) was added. After 60 min, the absorption was measured at 750 nm (Beckman DU-530 UV/VIS spectrophotometer, Germany). Sinapic acid was used for the calibration, and the results of duplicate analyses are expressed as sinapic acid equivalents. Sinapine, the major esterified sinapic acid compound shows a maximum absorption at 330 nm. 50 μl of the extracts were added to 2.45 ml methanol to quantify total hydroxyl cinammic acids at 330 nm and were expressed as sinapine equivalents.

2.4 Oxidation tests

Rapeseed oil was incubated at 40 °C and monitored for the formation of oxidation products. Antioxidants and extracts were added in methanol to the oil. Naturally occurring antioxidants in the rapeseed oil were removed by column chromatography prior to the addition of individual antioxidants and extracts. Conjugated dienes (CD) were measured according to Stöckmann et al. [10]. Hexanal was measured as indicator for secondary oxidation products with static headspace gas chromatography according to Frankel [11]. Samples were incubated at 70 °C for 15 min.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Extraction of phenolic compounds from rapeseed meal

Extraction of phenolic compounds from rapeseed meal was carried out with different solvent systems. 70% alcohol (7:3 alcohol/water) extraction systems showed the best properties (Fig. 3). The total phenol content ranged from 6 mg g–1 from MeOH:EtOH (methanol:ethanol, 1:1) extract to 18 mg g–1 from 70% MeOH extract expressed as sinapic acid equivalent (oil-free basis). The content of sinapine and other cinnamic acid derivatives was determined by spectrophotometric measurement of the absorption at 330 nm. The results are expressed as sinapine equivalents. The concentration ranged from 17 mg g–1 from MeOH:EtOH (1:1) extract to 29 mg g–1 from 70% MeOH extract (oil-free basis). It should be noted that, the comparatively high amount of cinnamic acids (sinapine equivalents) in contrast to the amount of total phenols (sinapic acid equivalents) is due to the non-specific principle of the methods. Other compounds apart from cinnamic acids may show absorption at 330 nm and the sensitivity of phenols to Folin–Ciocalteau reagent can markedly differ between the phenols. For further experimental purposes, 70% methanol was used.

Content of phenolic compounds in rapeseed meal extracts using different solvent systems; the total phenol content is expressed as sinapic acid equivalents; the total cinnamic acid content is expressed as sinapin equivalents; methanol (MeOH), ethanol (EtOH).

3.2 Content of free and bound phenolic compounds in rapeseed meal extract

70% methanolic rapeseed meal extracts of the meal have been classified into free phenolics, esterified phenolics and released phenolics as total phenols (sinapic acid equivalents). Free phenolics constituted 1.80–1.98 mg g–1, in bounded form 17–19 mg g–1, which on hydrolysis released 14–16 mg g–1 sinapic acids. Insoluble bound phenols from the meal residue were found to be around 0.2–0.5 mg g–1.

3.3 Content of phenolic compounds in commercial meals

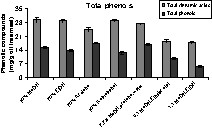

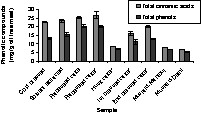

Commercial meals procured from Germany and India were analysed for their content of phenolic compounds using 70% methanol. Mustard and rapeseed husk cake showed low phenol content as compared to other commercial rapeseed cakes (Fig. 4).

Total phenols of different commercial meals; the total phenol content is expressed as sinapic acid equivalents; the total cinnamic acid content is expressed as sinapine equivalents.

* Rapeseed press cake from the same company.

3.4 Antioxidative activity of phenolic compounds in rapeseed triglycerides

3.4.1 Antioxidative activity of individual phenolic compounds

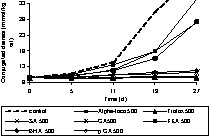

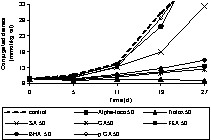

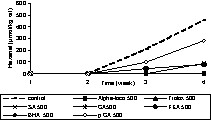

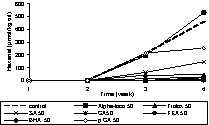

Prior to adding individual phenolic compounds to rapeseed oil, the oil was stripped to remove endogenous antioxidants of the oil, such as tocopherols. This purification step is necessary to assess the accurate antioxidative potential of the added individual phenolic compounds or extracts as endogenous antioxidants may interfere with the activity. The validity of the stripping procedure was verified by tocopherol analysis and the fatty acid pattern. The formation of conjugated dienes (primary oxidation products) and hexanal (secondary oxidation products) were monitored during the period of oxidation. The antioxidants were applied at concentrations of 50 and 500 μmol kgoil–1. The phenolic acids used were sinapic acid (SA), caffeic acid (CA), ferulic acid (FA), and p-coumaric acid (p CA). In addition, some reference antioxidants such as, butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA), Trolox and α-tocopherol (Alpha-toco) were included in the experiments (Figs. 5–9). The initial (0 d) concentration of conjugated dienes in stripped rape oil ranged from 8–9.7 mmol kgoil–1. This higher conjugated diene value of rape oil is attributable to the presence of other conjugated compounds, such as sinapic acid and its derivatives, absorbing at 234 nm. According to the oxidation tests (Figs. 5–9), sinapic acid at 500 μmol kgoil–1 was equally effective as other antioxidants like Trolox and BHA. In contrast, alpha-tocopherol was a better antioxidant at 50 μmol kgoil–1 than at 500 μmol kgoil–1 with respect to the inhibition of conjugated dienes. With respect to hexanal inhibition, both tocopherol concentrations (50 and 500 μmol kgoil–1) showed similar efficiency.

Effect of phenolic acids and commercial antioxidants on the oxidation (formation of conjugated dienes) of rapeseed oil at 40 °C in the dark. Sinapic acid (SA), caffeic acid (CA), ferulic acid (FA), p-coumaric acid (p CA), butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA), Trolox and α-tocopherol (Alpha-toco) were added to stripped rapeseed oil at a concentration of 500 μmol kgoil–1 (500).

Effect of phenolic acids and commercial antioxidants on the oxidation (formation of conjugated dienes) of rapeseed oil at 40 °C in the dark; sinapic acid (SA), caffeic acid (CA), ferulic acid (FA), p-coumaric acid (p CA), butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA), Trolox and α-tocopherol (Alpha-toco) were added to stripped rapeseed oil at a concentration of 50 μmol kgoil–1 (50).

Effect of phenolic acids and commercial antioxidants on the oxidation (formation of hexanal) of rapeseed oil at 40 °C in the dark; sinapic acid (SA), caffeic acid (CA), ferulic acid (FA), p-coumaric acid (p CA), butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA), Trolox and α-tocopherol (Alpha-toco) were added to stripped rapeseed oil at a concentration of 500 μmol kgoil–1 (500).

Effect of phenolic acids and commercial antioxidants on the oxidation (formation of hexanal) of rapeseed oil at 40 °C in the dark; sinapic acid (SA), caffeic acid (CA), ferulic acid (FA), p-coumaric acid (p CA), butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA), Trolox and α-tocopherol (Alpha-toco) were added to stripped rapeseed oil at a concentration of 50 μmol kgoil–1 (50).

Effect of 70% methanol (MeOH) rapeseed press cake extract as compared to other phenolic compounds on the oxidation (formation of conjugated dienes) of rapeseed oil at 40 °C in the dark; sinapic acid (SA), Trolox and 70% methanol extract added to stripped rapeseed oil at a concentration of 500 μmol kgoil–1 (500).

3.4.2 Antioxidant activity of rapeseed meal extract

The rapeseed meal extract (70% methanol) was added to stripped rapeseed oil in a concentration that was equivalent to 500 μmol per kg oil of total phenolic compounds. The extract showed similar antioxidative potential as sinapic acid at a concentration of 500 μmol kgoil–1 over a period of 13 days. The results indicate that rapeseed extracts could be effectively applied to increase oxidative stability of rapeseed oils.

4 Conclusion

Rapeseed meal extracts or by-products of oil processing contain significant amounts of phenolic compounds. Sinapic acid is the major phenolic compound present in the form of esters and glucosides. The current study indicates that phenolic compounds derived from rapeseed as well as extracts rich in phenolic compounds are able to effectively prevent lipid oxidation in rapeseed oil. Therefore, extracts from by-products of rapeseed oil processing can be used to stabilize refined oils with low amount of endogenous phenols. This concept can be applied to commercial refined rapeseed oils after the processing to stabilize the oils as with antioxidants naturally present in rapeseed. Antioxidants from rapeseed extracts can also be used in various food formulations instead of commercial ones. Rapeseed ranks currently the third source of vegetable oil (after soy and palm) and the third leading source of oil meal (after soy and cotton). Thus, any significant contribution related extraction of valuable compounds from rape meal would have overall a large contribution to the meal industry.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the DAAD for U. Thiyam is gratefully acknowledged. Sinapine thiocyanite were generously contributed by T.Z. Felde, Institut für Pflanzenbau und Pflanzenzüchtung, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany and Dr A. Baumert, IPB-Halle, Germany.