1 Introduction

Advances in chemical bonding theory, catalytic activity and reactivity of organometallic compounds have been impacted substantially by the burgeoning data on dynamic molecular processes. Two types in particular – sigmatropic and haptotropic rearrangements of either σ-bonded elements or π-bonded metal moieties, respectively – are promoted by the rich variety of polycyclic platforms available today. Although the capacity of these transformations is dictated by the topological properties of the interacting orbitals, the same organic substrate does not necessarily support both sigmatropic and haptotropic migrations with equal facility. In this vein, we here discuss some fascinating experimental data on metal complexes of dibenzpentalenes that have thus far remained unexplained.

Since their disclosure in 1971 [1], the major regularities of inter-ring haptotropic shifts have been defined by Albright et al. [2] and most recently surveyed by Oprunenko [3]. Disregarding competing intermolecular dissociative pathways, it has been shown that as MLn fragments traverse the faces of π systems, direct migration across the common bond between fused rings is typically a symmetry disallowed process (cf. sigmatropic shifts) and a circuitous minimum energy route is followed [2]. However, persistent ambiguities in the nature of transition states and intermediates make it difficult to distill kinetic and thermodynamic effects. Two bicyclic examples (vide infra) demonstrate these claims and provide the necessary design for other polycyclic models.

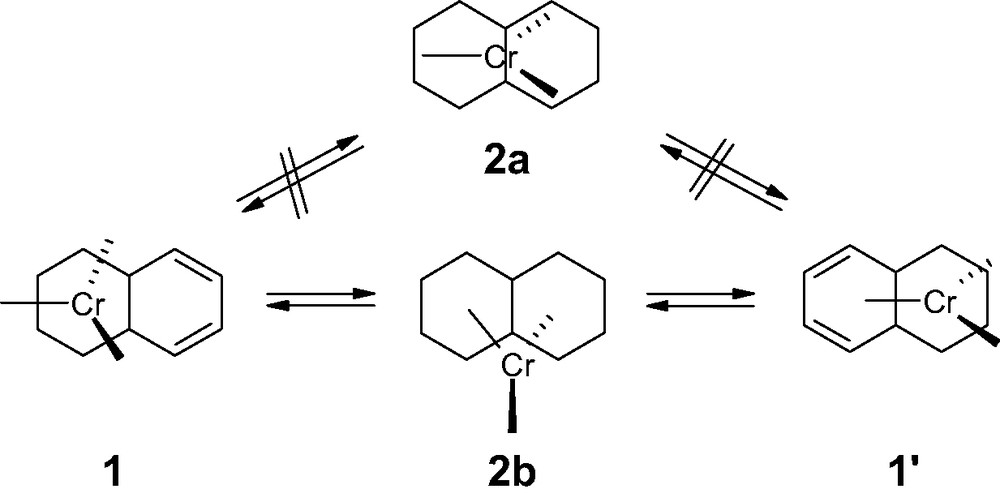

The migrations of a metal fragment over the two six-membered rings in appropriately substituted naphthalenes (as well as acenaphthenes or biphenylenes) have been the subject of a number of elegant experimental studies [4]. For the unlabeled (η6-C10H8)Cr(CO)3 1, the potential energy landscape (at the EHMO level of approximation) features both a transition state and an η3-allylic-type local minimum (2b) lying 27 and 21 kcal mol–1, respectively, above the ground state (Scheme 1) [2]. This contrasts with the DFT-predicted lowest energy η6-to-η6 degenerate rearrangement, which proceeds via a Cs-symmetric trimethylenemethane-type first order saddle point (ΔE = 30.4 kcal mol–1) only [5].

η6-to-η6 migratory pathway of a Cr(CO)3 unit in naphthalene.

An appreciable body of experimental information also exists for η6-to-η5 interconversions in indenyl-MLn complexes [6] and fluorenyl analogs [7]. In the asymmetric ligand, the pH-dependent rearrangement between the pentahapto (favored) and hexahapto isomers involves a non-least motion path and coordinatively unsaturated η3-allylic-type minimum, as demonstrated for the (indenyl)Fe(C5H5) system 3–5 (Scheme 2a) [2]. Benzannulation of the indenyl scaffold destroys the five to six ring internal plane of symmetry and the non-degenerate η6-to-η5 exchange proceeds through one of two peripherally bound η3 minima (pathways A or B, see Scheme 2b) [2]. Reversibility and isomer distribution aside, deprotonation of an [(η6-fluorene)MLn] species, 6, where MLn = Mn(CO)3+ or Fe(C5H5)+, has yielded isolable zwitterionic intermediates, 7a, which are perhaps better described as having an η5-bonded metal, and an exocyclic double bond, 7b, before undergoing migration to 9.

η6-to-η5 haptotropic shift in (a) indenyl and (b) fluorenyl systems, (3–5) and (6–9), respectively.

A π-manifold for η5-to-η5 haptotropic rearrangements is provided by the third bicyclic example, pentalene. Theoretical (EHMO level) considerations of the (pentalene)Fe(C5H5) system in both its cationic and anionic forms (10 and 11, respectively) identified two distinct bonding topologies [2]. In the former case, one of the primary frontier metal–ligand orbital overlaps is maintained during a least-motion transit; the calculated trajectory takes the FeCp moiety only 0.6 Å away from the midpoint of the central carbon-carbon bond (Scheme 3a). The addition of two electrons, as in 11, results in the loss of both iron-pentalene bonding interactions and renders the least-motion pathway highly unfavorable. Instead, the migration route is extended to the carbocyclic periphery via an η3-intermediate 12, as depicted in Scheme 3b. To generalize, Albright, Hoffmann et al. advanced an electron-counting rule such that when the total number of electrons supplied by the polycyclic ligand and the metal equals 4q + 2, where q = 2, 3, …, then haptotropic shifts passing directly under the common bond are forbidden. On the other hand, when this sum equals 4q, the process is partially allowed.

η5-to-η5 haptotropic rearrangement of FeCp in (a) cationic and (b) anionic forms of pentalene.

2 An aromaticity argument advanced

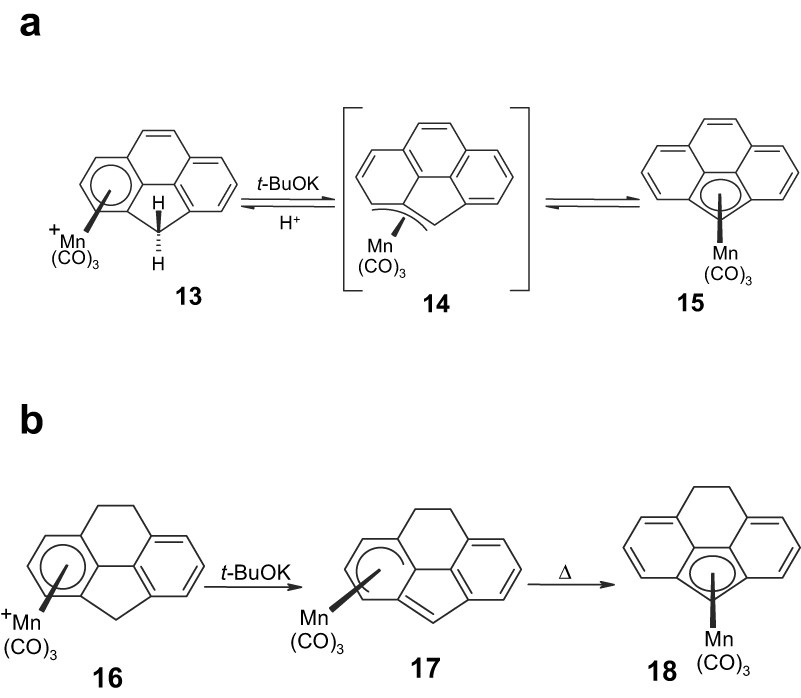

Although early attempts to intercept an η3-structure analogous to 4 were unsuccessful [8], indirect support for such an intermediate/transition state in fused polycyclic systems was claimed. Deprotonation of (η6-cyclopenta[def]phenanthrene)Mn(CO)3+, 13, yields the corresponding (η5-cyclopenta[def]phenanthrenyl)Mn(CO)3, 15, even at –40 °C (Scheme 4a) [9]. In contrast, deprotonation of the analogous (η6-8,9-dihydrocyclopenta[def]phenanthrene)Mn(CO)3+, 16, furnishes 17, in which the manganese maintains its attachment to the external six-membered ring (comparable to the fluorenyl complexes, 7). Complex 17 does not undergo a haptotropic shift to generate the centrally-bonded (η5-cyclopenta[def]phenanthrenyl)Mn(CO)3, 18, even when left at room temperature for 72 h; the rearrangement occurs only when the molecule is heated in hexane at 60 °C for an hour (Scheme 4b). This result was interpreted in terms of maintaining the 10π-naphthalene-type aromatic character in 14 (as shown in Scheme 4a) that is not available to the dihydro analog [9].

The facility of haptotropic shifts in (a) (cyclopenta[def]phenanthrenyl)MLn complexes 13–15 is diminished in (b) its dihydro analog, 16–18.

Gratifyingly, a recent X-ray crystallographic study [10] has unequivocally established the structure of exo-(η3-cyclopenta[def]phenanthrenyl)Mo(CO)2(η5-indenyl), which provides strong support for the intermediacy of exo-(η3-cyclopenta[def]phenanthrenyl)Mn(CO)3, 141. However, these data have been reinterpreted in terms of the enhanced strength of the η3-bonding mode in indenyl systems relative to that found in cyclopentadienyl complexes, and the normally invoked model of increased aromaticity in the transition state is not considered to be the major factor [11].

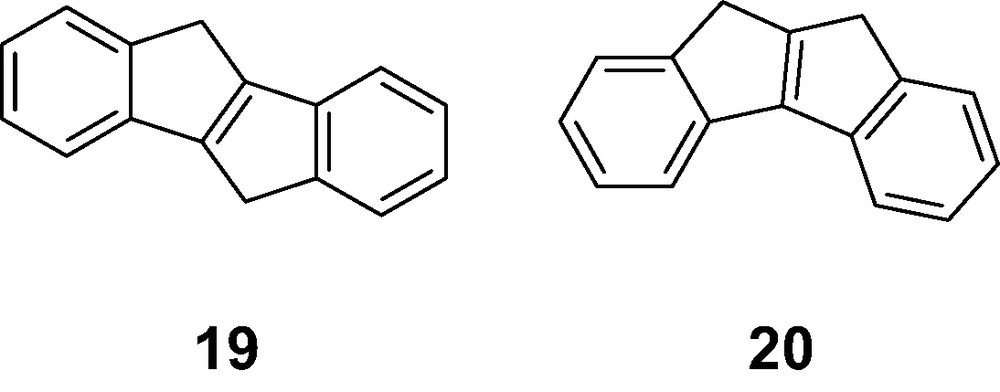

It would be instructive, therefore, to examine other multicyclic systems containing the pentalene, indene and/or naphthalene substructures that present potentially competitive pathways for η5-to-η5, η6-to-η5/η5-to-η6 and η6-to-η6 inter-ring haptotropic rearrangements. Theoretical studies of these processes, even at the extended Hückel level, may help to clarify general regularities associated with the nature of the transition states and the magnitude of the activation energies that need to be surmounted. Organometallic derivatives of the two fused polycyclic ligands 19 and 20 exhibit very different dynamic behavior and thus have been selected as challenging candidates for a preliminary qualitative mechanistic survey using potential energy surfaces (PES) calculated by the EHMO approach [12]2. Subsequently, the migration barriers indicated from the initial survey have been more extensively studied at the DFT level [13]3.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Anti- and syn-dibenzpentalene complexes

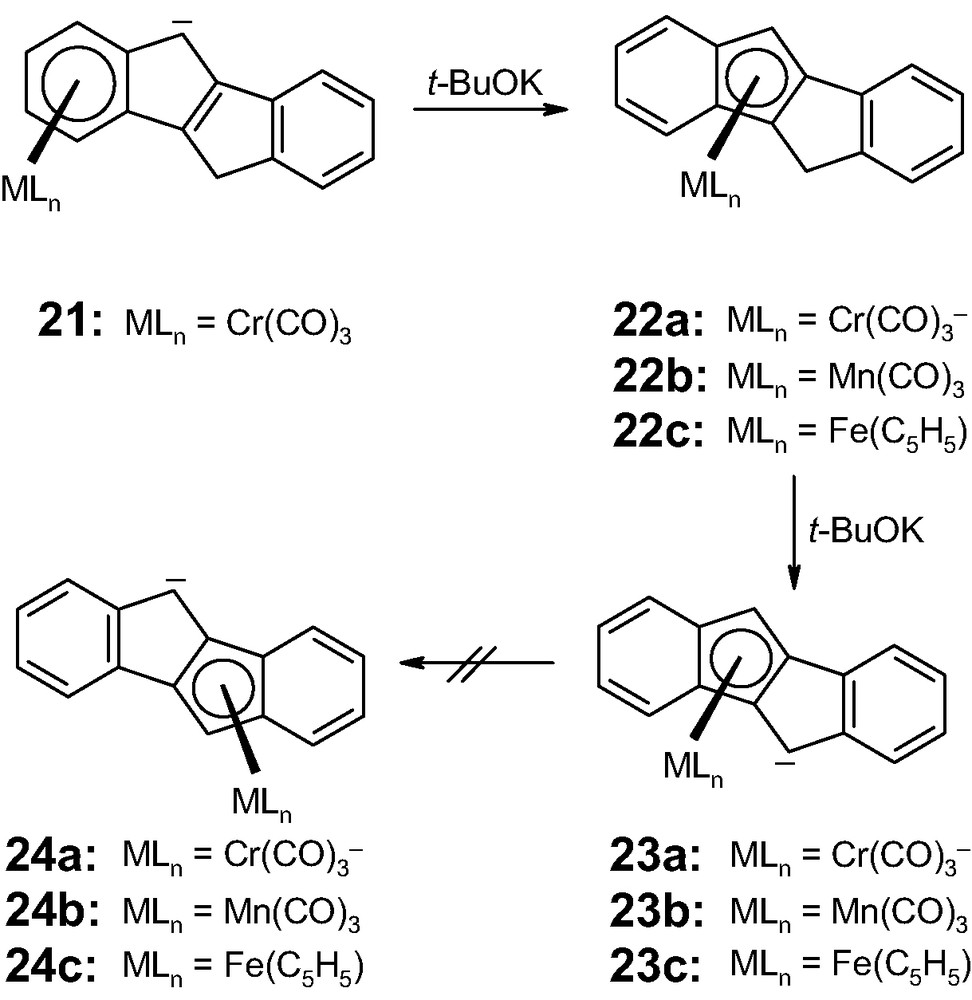

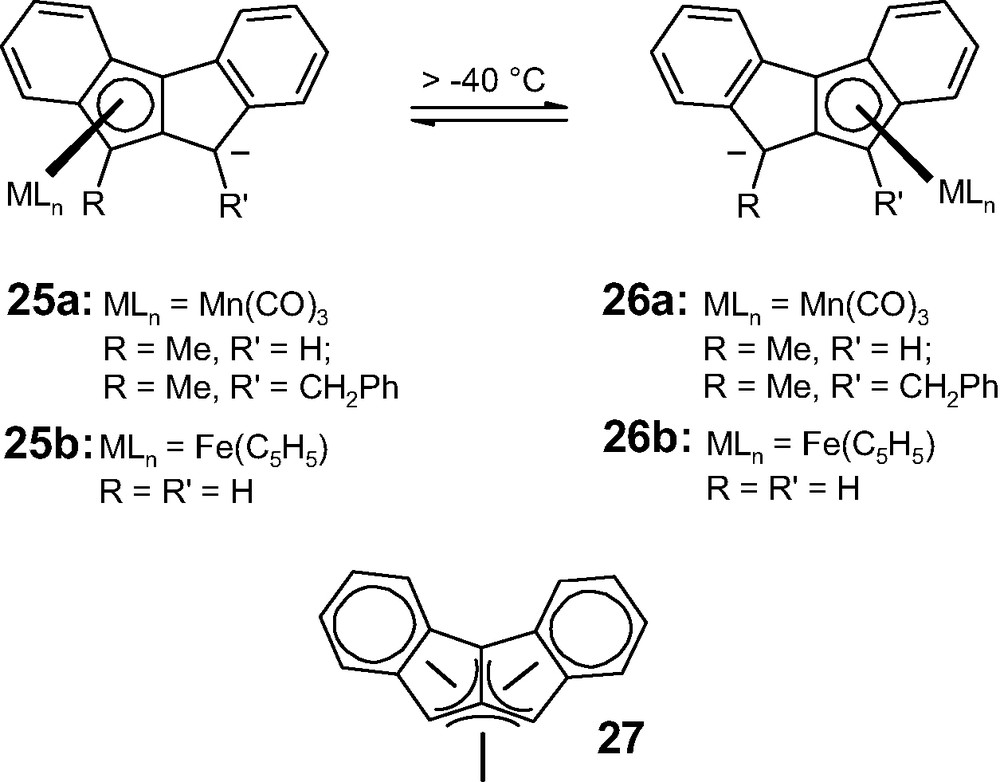

Despite synthetic excursions into benzannulated versions of pentalene [14], the first and only experimental evidence for an η5-to-η5 haptotropic rearrangement was provided by Ustynuk's laboratory in 1990 [15]. The chromium and manganese tricarbonyl complexes of the isomeric ligands, 5,10-dihydroindeno[2,1-a]indene and 9,10-dihydroindeno[1,2-a]indene, 19 and 20, which are more trivially named as derivatives of anti- and syn-dibenzpentalene, respectively, were prepared and their dynamic properties analyzed. The anionic complex [(η6-anti-dibenzpentalenyl)Cr(CO)3]1–, 21, rearranges readily and irreversibly into its η5 isomer, 22a, whereas the di-anionic complex [(η5-anti-dibenzpentalenyl)Cr(CO)3]2–, 23a, does not interconvert with its pentahapto derivative 24a (Scheme 5). Likewise, the corresponding mono-anionic manganese tricarbonyl complex, [(η5-anti-dibenzpentalene)Mn(CO)3]1–, 23b, fails to undergo η5-to-η5 interconversion. This is in complete contrast to the fluxional behavior of the isomeric species, [(η5-syn-dibenzpentalenyl)Mn(CO)3]1–, 25a, which exhibits rapid η5-to-η5 interconversion with 26a, even at –40 °C (Scheme 6); NMR lineshape analyses yielded an activation energy barrier of approximately 15 kcal mol–1.

η6-to-η5 rearrangements in organometallic complexes (21–24c) of 5,10-dihydroindeno[2,1-a]indene, 19.

η5-to-η5 rearrangements in organometallic complexes (25–26) of 9,10-dihydroindeno[1,2-a]indene, 20.

The very different dynamic behavior of the complexes derived from anti- and syn-dibenzpentalenes, 19 and 20, has been tentatively rationalized in terms of the symmetries of the pentalene frontier orbitals [15], but no simple picture has emerged. In 19, the ligand has a twofold axis, whereas in 20 there is a mirror plane bisecting the bond shared by the two five-membered rings. Clearly, it is not a question of the number of electrons supplied by the ligand and the metal totaling 4q + 2 in one instance, and 4q in the other, since these molecules are isomeric.

These fascinating results prompted us to calculate PES for the migration of an MLn unit across the anionic forms of 19 and 20. Initially, the organometallic fragment selected was (C5H5)Fe+, which is isolobal to Mn(CO)3+ but does not require that one take account of the different orientation of the tripod at each point since rotation about the metal-Cp axis has a very low barrier [16]. Following the method used previously for (pentalene)FeCp+, the iron was held at a constant distance of 1.59 Å from the plane of each dibenzpentalenyl ligand, and allowed to move across the polycyclic framework in steps of 0.1 Å to generate the PES shown as Figs. 1 and 2.

Potential energy hypersurface (EHMO-calculated) for the migration of an [Fe(C5H5)]+ fragment over the di-anion of the anti-dibenzpentalene framework, 19. Solid contour lines are incremented in units of 5 kcal mol–1, and the reaction path is superimposed as a dotted line.

Potential energy hypersurface (EHMO-calculated) for the migration of an [Fe(C5H5)]+ fragment over the di-anion of the syn-dibenzpentalene framework, 20. Solid contour lines are incremented in units of 5 kcal mol–1, and the reaction path is superimposed as a dotted line.

In viewing the PES for the anti isomer 19 (Fig. 1), the most obvious result is the greatly disfavored (~72 kcal mol–1) least-motion pathway directly across the common bond between the five-membered rings (see 23c → 24c in Scheme 5). Moreover, the alternative route that bypasses the center of this bond still requires that the migrating group surmount a barrier of ~45 kcal mol–1 and, as mentioned previously [15], this η5-to-η5 shift is not observed experimentally for the manganese and chromium complexes shown in Scheme 5. Interestingly, the η6-to-η5 haptotropic shift, 21 → 22a, does proceed irreversibly, and the PES indicates why this should be so. When the CpFe moiety is initially bonded to the six-membered ring it must—and experimentally does in the case of 21—traverse a barrier of ~33 kcal mol–1 before attaining the metallocenyl-type structure (cf. 22a). However, the reverse process starts from the η5-isomer that is approximately 18 kcal mol–1 more stable than the η6-bonded structure, (cf. 21), and so raises the barrier to more than 50 kcal mol–1, and renders the η5-to-η6 haptotropic shift both thermodynamically and kinetically non-viable. These values should be compared with the corresponding results for the (indenyl)FeCp system for which the η5 geometry was calculated to be favored over the η6 structure by about 19 kcal mol–1, and the η6-to-η5 barrier was estimated as 35 kcal mol–1 [2].

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the situation is radically different for the corresponding syn isomer 20, for which the η5-to-η5 haptotropic shift process shown in Scheme 6 occurs readily with an experimental barrier for the manganese complex, 25a, of approximately 15 kcal mol–1 [15]. The PES for [(syn-η5-dibenzpentalenyl)FeCp]1– reveals a relatively low energy pathway by which the organometallic fragment can migrate between the five-membered rings. The favored trajectory takes the iron atom almost directly underneath a ring junction carbon to yield an intermediate structure only 10 kcal mol–1 less stable than the η5 minimum; the highest point on this route is approximately 25 kcal mol–1 above the ground state, which is about half of that required in the anti-analog 23c.

One can relate these calculations and the experimental observations on the dibenzpentalenyl complexes back to our previous discussion concerning (cyclopenta[def]phenanthrenyl)Mn(CO)3, 15, and its dihydro analogs, 17 and 18. In the former system, one could invoke the aromatic character of the intermediate (and/or transition state), 14, which lowers the activation energy for the migration process, somewhat analogs to Basolo's famous ‘indenyl effect’ for ligand displacements in (indenyl)Rh(CO)2 versus (cyclopentadienyl)Rh(CO)2 complexes [17]. In [(syn-dibenzpentalenyl)FeCp]1–, 25b/26b, the intermediate possesses two 6π aromatic rings while the metal is essentially in an (η4-trimethylenemethane)MLn local environment, as in 27.

For comparative purposes, Fig. 3 depicts the EHMO-calculated trajectory for the η5-to-η5 haptotropic shift in [(syn-dibenzpentalene)Mn(CO)3]1–, 25a (R = R′ = H), and yields an activation energy barrier of 14 kcal mol–1. It is noticeable how the favored orientation of the tripod changes during the migration such that at the ‘trimethylenemethane structure’ the manganese is essentially in an octahedral environment as would be anticipated for a d6 [Mn(CO)3]+ fragment4. As in the iron derivative, the η6-to-η5 and η5-to-η6 routes are more energetically demanding, with estimated barriers of 26 and 41 kcal mol–1, respectively.

Having established the general behavioral patterns for the anti- and syn-dibenzpentalene complexes 23 and 25, it was deemed appropriate to evaluate the migration barriers at a higher level of computation, namely DFT. For the (syn-dibenzpentalene)tricarbonylchromium dianion, 23a, the geometry- and energy-minimized ground state was the expected η5-structure, as found at the EHMO level; the barrier for migration of the chromium towards the trimethylenemethane-type structure was evaluated as 9.7 kcal mol–1. In the analogous manganese mono-anionic species, 25a (R = R′ = H), the calculated energies for the η5-isomer and for the trimethylenemethane-type η4-structure lie within 1.3 kcal mol–1 of each other, suggesting that both sites may be partially populated. A search was made for the transition state connecting these two minima and a point was located (and characterized with a single negative frequency of 157 cm–1) lying 11.6 kcal mol–1 above the ground state. The manganese was calculated to be 1.86 Å below the ring center at the η5-site, and 1.99 Å below the ring junction carbon at the η4-position; however, at the transition state, the metal is now 1.95 Å from the plane of the polycyclic ligand. The NMR-derived barrier for the interconversion of 25a and 26a was reported as 14.9 kcal mol–1, but is somewhat complicated by the existence of the temperature-dependent equilibrium [15].

In contrast, although the DFT calculations revealed an η5-bonded energy minimum for the anti complex 25b, we were unable to locate a transition state for migration of a metal between the two five-membered rings. Thus, the general features of the potential energy landscape indicated at the EHMO level of approximation are supported by higher level calculations.

4 Concluding remarks

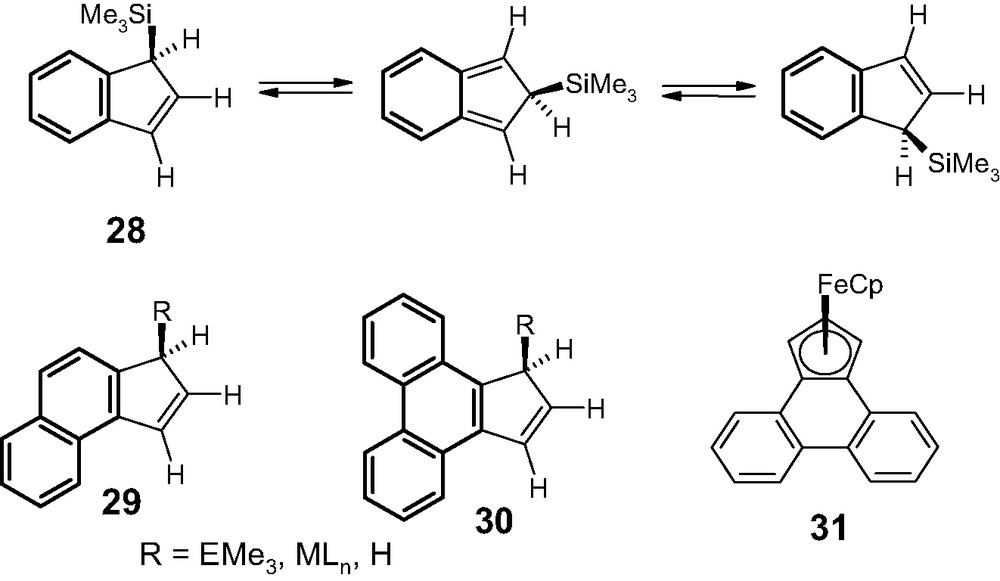

These patterns of haptotropic shifts, which are controlled by the interactions of the MLn fragment with the π-manifold of the ligand, may be profitably compared with the sigmatropic migrations of R3M groups (M = Si, Ge or Sn) or of (C5H5)(CO)2Fe across similar polycyclic frameworks [19,20]. Beyond orbital considerations, the energy requirements of both types of rearrangements can be correlated with the aromatic character of the transition state and/or intermediates.

For example, the barriers to [1,5]-suprafacial silatropic shifts in the indenyl system 28 (Scheme 7) are dramatically reduced from 25 kcal mol–1 to 22 and 18 kcal mol–1, respectively, upon mono- and dibenzannulation (cf. 29 and 30), which allows the isoindene intermediates (and their accompanying transition states) to retain an increasing degree of aromaticity [21]. In fact, the isoindene derived from cyclopenta[l]phenanthrene (30, R = H) is sufficiently long-lived as to undergo a Diels–Alder dimerization with its progenitor [22].

Sigmatropic shifts in a series of benzindenes (28–30).

Metal π-complexes of fused polycycles may present a variety of competing reaction pathways for (η5-to-η5, η6-to-η5/η5-to-η6 and η6-to-η6) haptotropic shifts, as demonstrated by the cases examined herein. For these processes, the transition state (or intermediate) is generally of the η3 or η4 type such that cyclic π-electron delocalization can be maintained as the MLn traverses a circuitous route on the molecular periphery. To this end, indene (3) and fluorene (6) skeletons are suitable substrates for η6-to-η5 migrations; however, depending on their sites of attachment, further fusion of benzene rings, such as in 31 [23], can actually diminish the aromatic stabilization of certain isomeric forms and thus limit the migratory possibilities. These kinetic and thermodynamic trends are not easily discerned from or related to the constitution of the organic ligand, providing merit to the use of an initial EHMO approximation of the energy landscape. Subsequent application of more rigorous quantum-mechanical methods to the study of haptotropic transformations enhances both the accuracy of mechanistic details, particularly the nature of saddle points, and the predictive aspects of this electronic structure and bonding argument.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). S.B. gratefully acknowledges both the Government of Ontario and NSERC for graduate scholarships; C.M.S. thanks NSERC for a post-doctoral fellowship. We thank Dr. M. Tacke for his interest, and a reviewer for helpful comments.

1 However, analogous η3-fluorenyl complexes are known. See, for example, [10].

2 Extended Hückel calculations were carried out by using the program CACAO, Version 5.0, 1998.

3 All calculations were corrected for zero point energy and were verified by appropriate frequency calculations. Calculations were carried out by using G03 Rev B 04 with the B3LYP functional and Pople's 6-31G* basis set for all atoms.

4 Although (trimethylenemethane)Mn(CO)3+ has not, to our knowledge, been reported, the analogous (TMM)Fe(CO)3 system does indeed adopt the staggered orientation [18].