1 Introduction

Successful utilization of membrane technology has been greatly limited by membrane fouling. This fouling phenomenon increases operation and maintenance costs by deteriorating membrane performances (flux decline vs time, zeta potential changing during time, etc.), and ultimately by shortening membrane life. Low-pressure membrane processes, namely ultrafiltration (UF) and microfiltration (MF), play a major role in the production of drinking water free of health hazards. They have been increasingly used in drinking water treatment as an alternative technology to conventional filtration and clarification in order to remove particles, turbidity, and microorganisms from surface and groundwater to meet stricter regulations established in drinking water quality. Moreover, during the last decade, these membrane processes have found increased application in the treatment of domestic and industrial effluents in the production of water suitable to reuse. Concerning the possibilities of pre-treatment, the membrane pre-treatments are the most appropriate ones to be used because of the ease of operation, lesser space requirements and lesser usage of chemicals. Thus, compared to conventional pre-treatments such as coagulation–flocculation–sand filtration, membrane processes like MF and UF are more convenient and efficient [1]. Together with improved maintenance procedures, such as filtrate backwashing and air scouring, significant flux and pressure recoveries are achievable with minimal use of chemicals. Using membrane methods of pre-treatment will also go in tandem with the recent trend of increasing packing density of spiral wound RO elements.

Natural organic matters (NOM) and specially humic acids [2–9] play a major role in membrane fouling and influence mainly the flux decline. Humic substances are typically characterized by a physical and chemical heterogeneous nature which derives from: (a) the absence of a discrete structural and supramolecular level; (b) the wide variety of sizes and shapes assumed in the solid and colloidal states; (c) the occurrence of complex aggregation and dispersion phenomena in aqueous media; (d) the various degrees of roughness and irregularity of exposed surfaces. These properties have an important role in determining the physical, chemical, and biological reactivity of humic substances toward mineral surfaces, metal ions, organic chemicals, plant roots, and microorganisms in soil [10]. Membrane fouling by humic substances (HS) is influenced by the properties of these substances, the characteristics of membrane, the hydrodynamic conditions, and the composition of the feed solution. A better comprehension of these factors is important to a better control of membrane fouling. Membrane pore size, charge and hydrophilic/hydrophobic character will also affect membrane fouling. Furthermore, pH and ionic strength will also have an important role to play. When fouling is complex and poorly understood, membrane autopsy is a powerful diagnostic tool that can help to enhance system performance. The best membrane autopsy approach today is to develop more in situ tools which engage non-destructive analysis of the membrane materials, like hydraulic permeability or streaming potential (SP) measurements [11,12].

Therefore, there is an economic reason to the use, research and development in this area of membrane pre-treatment. Current research also emphasized the importance of pilot testing as measured performance of the combined effect of the membrane, system configuration and the dynamic cake layer that formed on surface of the membrane during filtration.

The comparison of MF and UF membranes as raw water pre-treatment operations shows a more dramatic hydraulic permeability decrease for the MF than the UF, as usually observed. Then we decided to work on the intensification of UF operation in order to elaborate a sustainable seawater pre-treatment for the future.

The objective of our work is to contribute to better understand the mechanism of fouling of a humic acid solution during UF operation on a regenerated cellulose membrane (RC) having a molecular weight cut-off of 100 kDa. In the present article, we combined two approaches, one macroscopic and another microscopic. Using the macroscopic one we determined the modified fouling index (MFI-UF) which gave the fouling potential of the feed solution [13], the hydraulic permeability evolution vs time and the cake resistances under a pressure of 2 bar (membrane resistance, resistance after HA adsorption and cake formation) [14]. Using the microscopic approach we attained the fractal dimension (FD) [15] of the humic acid cake formed from filed emission scanning electron microscopic (FESEM) images. Furthermore, we have characterized the presence of low-molecular-weight fractions of the HA in the membrane pores using transmembrane SP measurements with a new semi-automatic apparatus presented here for the first time. To achieve this work, preliminary experiments with seawater using the RC-UF 100-kDa membrane such as variations in hydraulic permeability and SP before and after filtration were conducted.

2 Theory

2.1 Fractal dimension

Euclidian geometry describes regular objects such as points, curves, surfaces and cubes using integer dimensions 0, 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Associated with each dimension is a measure of the object such as the length of a line, area of a surface and volume of a cube. However, numerous objects found in nature, such as coastlines, rivers, lakes, porous media are disordered and irregular, which cannot be described by Euclidian geometry due to the scale-dependent measure of length, area, and volume. These objects are called fractals and their dimensions are non-integral and defined as fractal dimensions. A fractal object can be divided into parts, each of which is similar with the whole. However, self-similarity in a global sense is seldom observed in actual applications. Numerous objects found in nature do not exactly exhibit self-similarity, but statistical self-similarity, which implies that these objects exhibit the self-similarity in some average sense [15].

2.1.1 Determination of fractal dimension using the box counting method

The well-known box counting method is used to determine the fractal dimension (FD). FD is obtained from the slope of the double-logarithmic graph

| (1) |

2.2 Modified fouling index (MFI) theory

MFI parameter gives an idea of the fouling potential of the feed. It is based on the cake filtration mechanism, as recently reported by Schippers et al. [13]:

| (2) |

The filtration occurs usually in three stages: (i) the first part is the blocking of the pores, (ii) the second part is the gradual formation of the cake, and (iii) the third part is the compression of the cake. When there is a formation of an incompressible cake, the relation between t/V and V is showed to be linear and the slope of the linear relation will give the indicator MFI which corresponds specifically to the fouling potential of the feed solution. The results of the test are thus a series of measurements of time and cumulated volumes of the permeate.

2.3 Resistance in series model

From Darcy's law, the flux is directly proportional to the transmembrane pressure, as can be written by Eq. (3):

| (3) |

| (4) |

2.4 Streaming-potential (SP) theory

According to the Helmholtz–Smoluchovsky equation, the streaming potential (denoted Δϕ/ΔP), is given by

| (5) |

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Membranes and modules

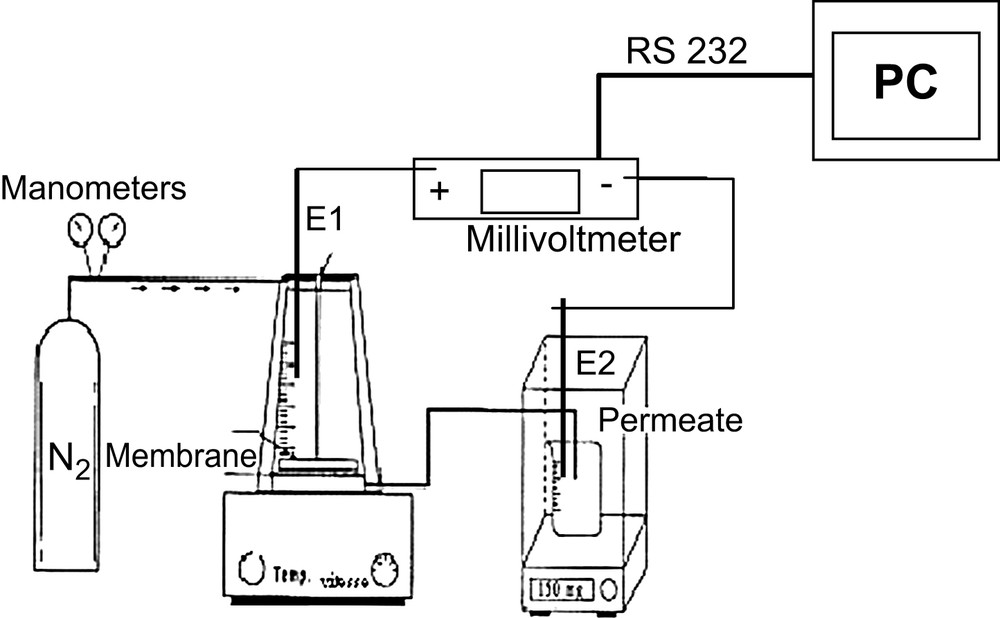

The membrane used in this study is a flat sheet UF membrane of regenerated cellulose (denoted RC-UF) purchased from Millipore, (France) with a nominal molecular weight cut-off (NMWCO) of 100 kDa. The filtration cell is a dead-end cell (Model 8200, Amicon®) (see Fig. 1), purchased from Millipore (France). Membranes tested are registered as N°K4SN9799 and purchased from Millipore (France). The permeate mass is determined using an electronic balance with an accuracy of 0.1 mg.

Schematic diagram of the dead-end UF design laboratory pilot.

3.2 HA solution

Humic acid solution of 5 mg/L concentration was prepared by dissolving humic acid (supplied by Aldrich, France) in ultrapure water (milliQ water system, Millipore, France). The pH of the obtained solution was determined as 6.5. Humic acid particles have a size distribution around 250 nm and a zeta potential of −30 mV (determined with Zetasizer 4 apparatus, Malvern Inc., US) (see Fig. 2). All experiments were conducted at room temperature (20 °C).

Evolution of the zeta potential and the average size of humic acids particles vs pH.

3.3 FESEM analysis

FESEM apparatus is employed with a filed emission gun (JSM-6301F from JEOL, France). Images obtained are from secondary electrons under 3-keV beam energy with magnifications situated between 2000 and 10,000. RC membranes are dissected and glued to a carbon support. Finally, carbon of 2-nm thickness was deposited by evaporation under vacuum (BAL-TEC MED 020 Balzers Lichentstein apparatus).

3.4 Fractal dimension determination

3D-fractal dimensions (3D-FD) was determined using Image J software from the FESEM images plotting log N vs log ɛ, a straight line of slope 2D-FD, enabling the FD of the cake surface or of the membrane surface, to be determined.

3.5 Streaming potential measurements

Fig. 3 shows a photography of the newly designed SP apparatus to follow the zeta potential variations of the membrane before and after fouling with HA solution. To this system two Ag/AgCl electrodes are connected, which in turn are connected to a millivoltmeter (PHM250 from Radiometer Analytical, France) presenting a high enter impedance connected via an RS232 to a PC. The software (denoted proFluid 1.2) was developed in collaboration with NEOSENS (Toulouse, France). For each transmembrane pressure value a corresponding potential difference was indicated on the millivoltmeter, which is automatically transposed to a PC instantaneously. The same experiment is conducted under different pressures (from 0.5 to 3 bar, with a 0.5-bar increment). SP and the correlation coefficient R2 are automatically generated. A mean average value of 1 mV/bar is attached to each SP measurement.

Photography of the new semi-automatic SP measurement apparatus and its software proFluid 1.2 (university of Angers, UMR-MA105, Feb. 2006).

The sign of the SP directly yields the sign of the net charge of the membrane, i.e., the global charge behind the shear plane. We connected the positive potential to the feed and the negative to the permeate, then from the slope we obtained directly the sign of the membrane pore walls and consequently the charge density of the membrane pore walls [12,16].

3.6 Seawater experiments

A preliminary experiment was conducted by the ultrafiltration of a seawater sample from Biarritz (France) using the RC 100-kDa membrane during 2 h at a pressure of 3 bar using the pilot design described in Fig. 1. Hydraulic permeability and SP before and after the filtration has been estimated. The SDI of seawater was estimated to be 3.5. Then seawater was pre-filtered on coal, as previously described [17].

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Resistance results

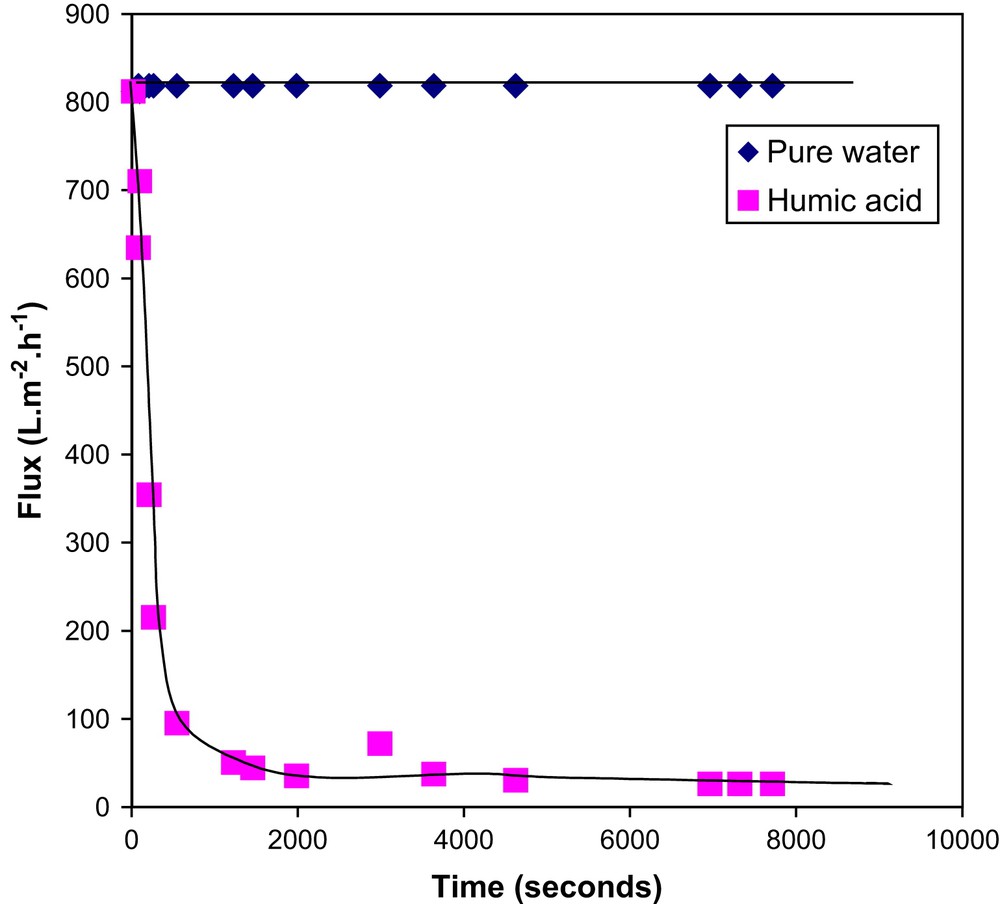

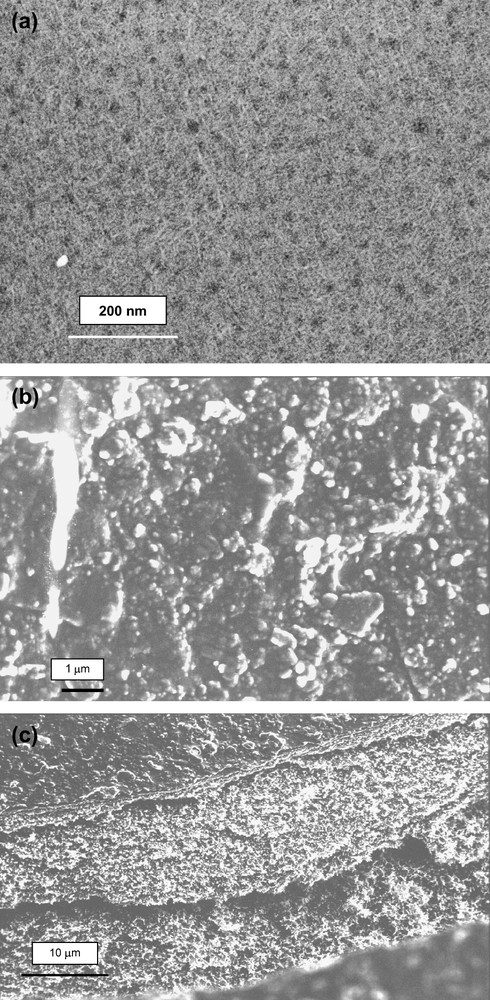

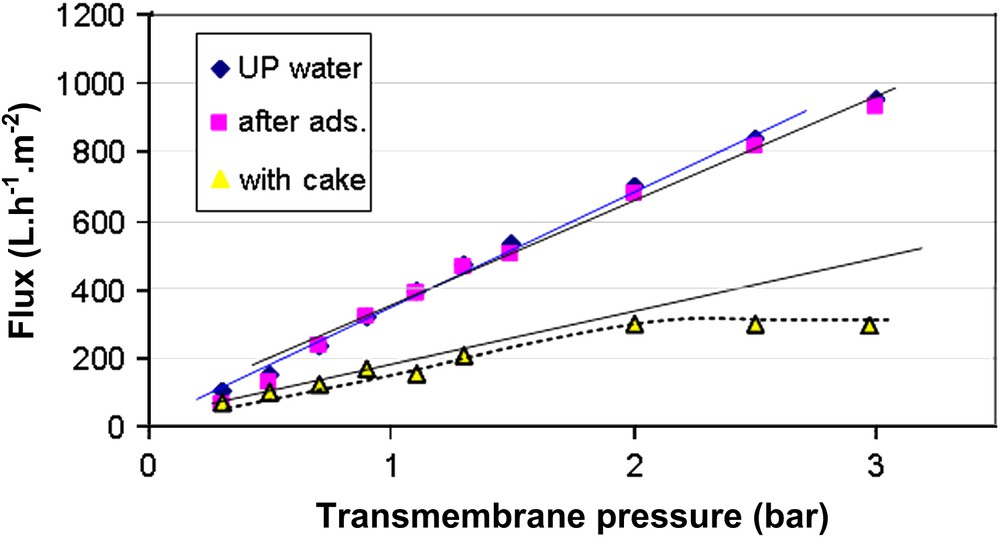

Ultrafiltration (UF) of humic acid solution (5 mg/L, pH 6.7) was carried out at a constant transmembrane pressure of 2 bar for 8000 s. Fig. 4 shows the variation of flux with time both for pure water and for humic acid. It is shown that the pure water flux remained constant (800 L m−2 h−1). For humic acid, the filtration was rapid during the first few minutes, then it became gradual and reached a quasi-steady state. At the end of the experiment, the decrease of the flux from the initial value was 90%. Humic acid particles were deposited and accumulated on the membrane surface, which gradually developed a cake layer, as illustrated in Fig. 5b and c. Resistance in series model helped to confirm the results about cake filtration formation. As indicated in Fig. 6 in the linear range of the curves, the membrane hydraulic permeability was 390 L m−2 h−1 bar−1; permeability after adsorption was 380 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 and the permeability with the cake was 122 L m2 h−1 bar−1. The determined values are reported in Table 1. From these results we can understand that the cake formation is the major cause of fouling. Membrane resistance contributes to 46% of the total resistance. Adsorption resistance is only 2%. The cake resistance is the major factor, which is 52% of the total resistance.

Evolution of flux with time during the ultrafiltration of HA solution in milliQ water ([HA] = 5 mg/L, pH = 6.7, ΔP = 2 bars).

(a) FESEM image showing the clean RC-UF membrane before filtration (magnification 50,000×); (b) FESEM image showing the deposition of humic acid ([HA] = 5 mg/L, pH = 6.7, ΔP = 2 bars) on the surface of the RC-UF membrane (magnification 10,000×); (c) (a) FESEM image showing a cross-section of the humic acid cake formed on the RC-UF membrane (magnification 2000×).

Evolution of flux with transmembrane pressure for the RC 100-kDa membrane with ultrapure water: initially, after adsorption with humic acid and after 2 h filtration of the humic acid solution.

Resistance values and % of the total resistance of the RC membrane before and after fouling by the HA solution

| Membrane resistance (Rm) | Adsorption resistance (Ra) | Cake resistance (Rc) | Total resistance (Rt) | |

| Resistance values (×10−12) m−1 | 0.92 | 0.02 | 2.01 | 2.95 |

| % Values of the Rt | 46 | 2 | 52 | 100 |

The flux decline (loss of 90% of the initial value after 8000 s) is attributed to the formation of a cake, as illustrated on the SEM images (Fig. 5b and c).

Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of the membrane before and after filtration (Fig. 5a and b) shows the clean membrane surface and the cake deposit on the membrane, respectively. The RC-UF membrane surface before and after filtration by humic acid had totally different morphologies.

Furthermore, during our SEM analysis we analysed a section of the cake (Fig. 5c) which in a magnified form (10,000×) revealed fractal structures (Fig. 7a). From the same image a threshold image is generated using image J software (see Fig. 7b) which permitted us to obtain the FD values. The thickness of the cake from Fig. 6b is estimated as 30 μm.

(a) SEM image showing the humic acid cake deposit in the form of fractal structures (magnification 10,000×); (b) threshold image of (a).

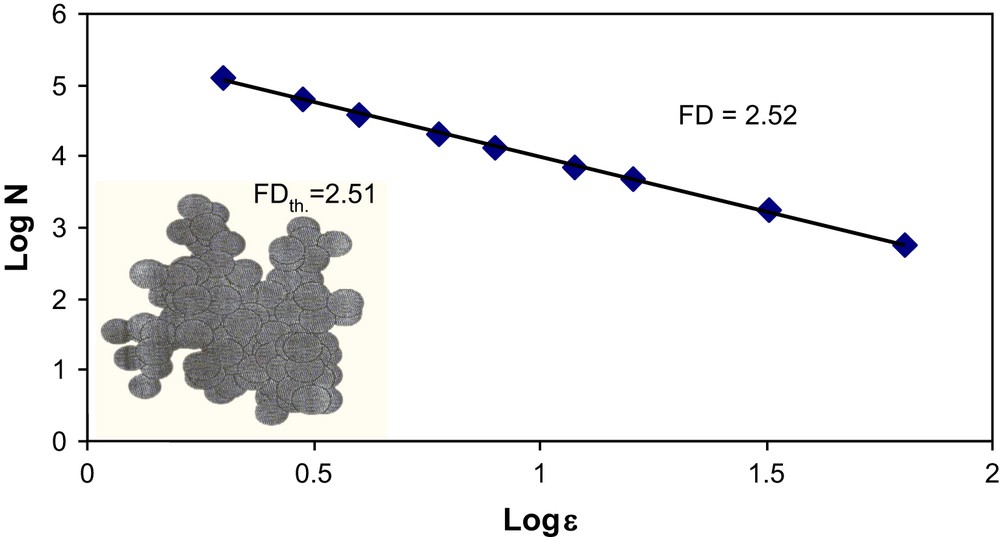

4.2 Fractal dimension results

Fractal dimension FD, is calculated using the well-known box counting method reported by Mandelbrot [15]. The FD values are reported both in Table 2 and in a double-logarithmic graph in Fig. 8. The slope of the double-logarithmic graph gave the fractal dimension of the image in three dimensions as 2.52. This value was found to be in good correlation with that of particle–cluster aggregation underlying diffusion-limited aggregation, as reported by Witten et al. [18]. The authors also described that particle–cluster aggregation has been shown to lead to flocs with a well-defined fractal dimensionality of 2.51 in three dimensions. Senesi et al. [19] reported that humic acid suspensions in aqueous medium are susceptible to exhibit fractal structures. The authors also found that the value of FD can also change according to different operating conditions, like humic acid solution concentration, pH and ionic strength.

3D-fractal dimensions (3D-FD) values for 100 kDa cleaned and fouled membranes, on the surface and inside the cake layer

| Clean surface | Fouled surface | Humic acid cake | Theoretical FD value | |

| Fractal dimension (3D-FD) | 2.89 | 2.50 | 2.52 | 2.51 |

Double-logarithmic plots for the determination of FD for humic acid cake + three-dimensional model showing that particle–cluster aggregation comes under diffusion-limited aggregation.

In our study, the aggregates formed are having a complicated multi-branched structure. In these cases, diffusion of the species toward the surface (or heat away from it) can be the rate limiting process [18]. Meakin [20] reported that diffusion-limited deposition on fibres and surfaces also results in open dendrite structures with a “fractal” nature.

Recent results from Aimar et al. [21] show that FD decreases as the hydraulic permeability decreases. On the contrary Meng and Zhang [22] linked FD decrease to porosity increase.

In our case, the presence of the cake changes totally the FD of the initial membrane, FD values are 2.89 and 2.52 for the initial membrane and with the cake, respectively (see Table 2). But we cannot correlate FD with hydraulic permeability decrease because the cake has replaced the RC material by a new material which has its proper FD. More experiments have to be conducted to search correlations between FD values and the macroscopic parameters. We will study the effect of transmembrane pressure, nominal molecular weight cut-off of the membrane, pH and also HA concentration.

Thus, as a microscopic approach, FD can be used as an interesting parameter to describe cake formation and complete the classical flux decline macroscopic approach.

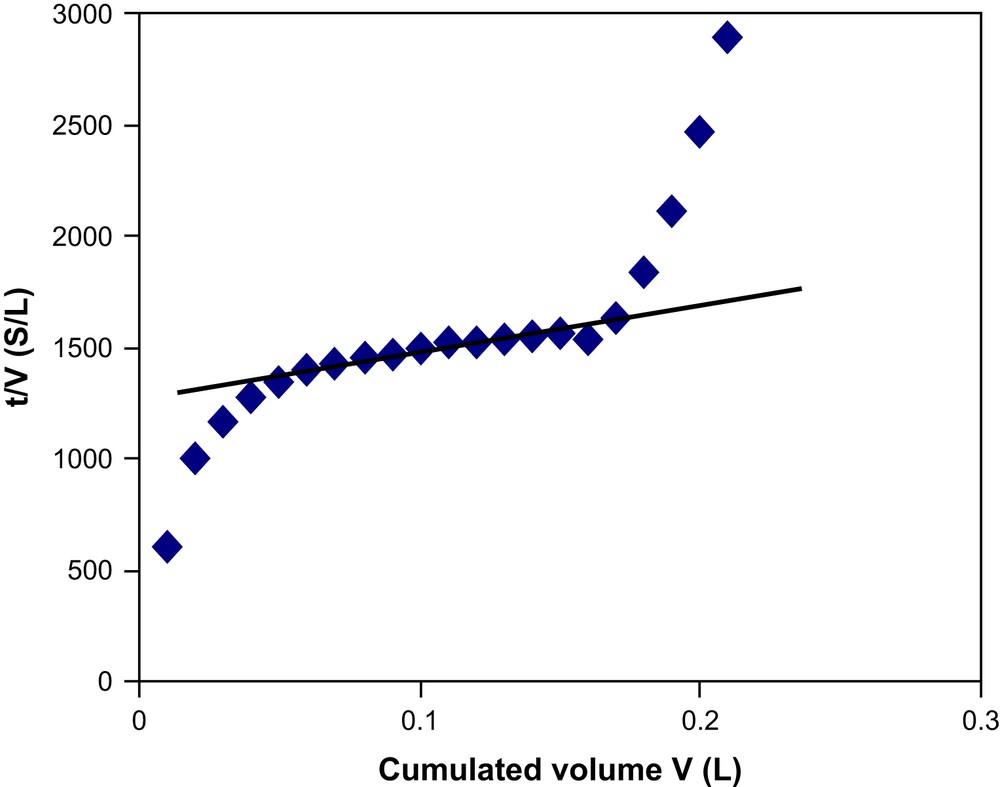

4.3 Fouling indice results

Firstly we have determined the classical SDI (silt density index) following the usual recommendations. The value obtained with the HA solution is 6.2 ± 0.3. SDI is not enough informative as it is dedicated to RO operations. Then a new index denoted as modified fouling index (MFI), which is a macroscopic parameter and a very good indicator of the fouling potential of the feed, is determined as reported by Schippers et al. [13]. The curve obtained (Fig. 9) has three distinct portions which indicate three different stages of filtration. The first part is the adsorption of the solute to the membrane surface, the second part is cake formation and the third part is cake compression. To get the MFI-UF value we determined the slope of the second portion of the curve and obtained 1650 s/L2.

Evolution of t/V with V for the determination of modified fouling index (MFI).

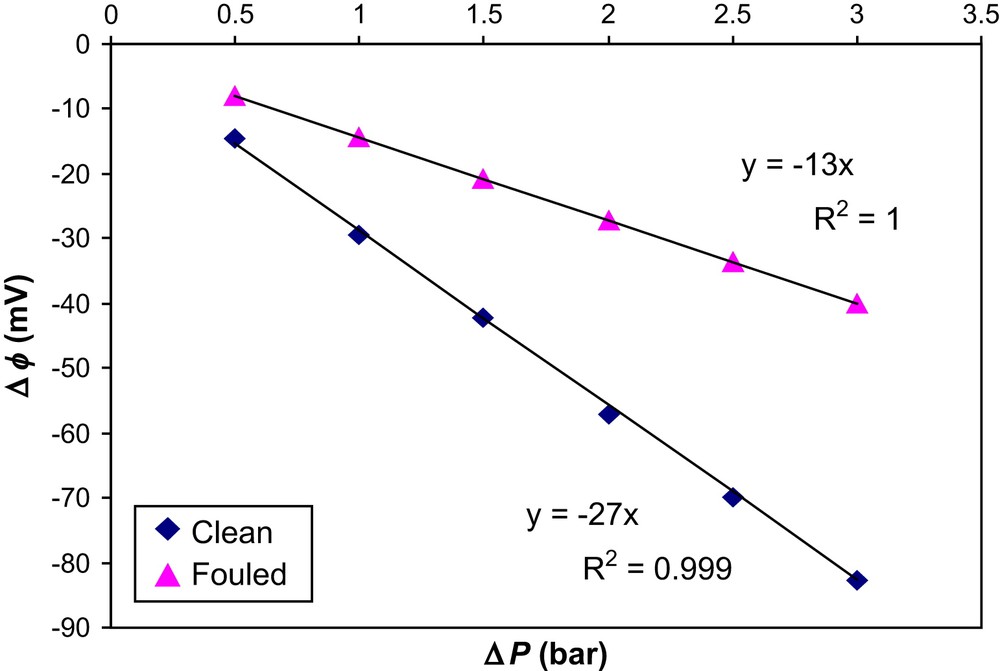

4.4 Streaming potential results

We determined the streaming potential (SP) of the membrane before and after filtration with humic acid under fixed pH conditions (pH = 6.5). Fig. 10 illustrates the variation of potential difference(mV) vs transmembrane pressure (bar) obtained using the SP measurements design described above. Both clean and fouled membranes were compared. The charge of the clean membrane was −27 mV/bar and that for the fouled membrane was shown to be −13 mV/bar. From these values, we can conclude that after the cake formation on the surface of the membrane, the charges carried by the membrane pore walls have drastically reduced. This modification of internal pore charge can be attributed to the penetration of lower-size humic acid fractions into the membrane pores which caused also fouling inside the membrane, as recently reported [2]. The same authors [2] characterized the molecular weight of humic acid fractions and found that humic acid fractions extracted from surface water were having molecular weights in the range of 1000–1500 Da, which is very low and can be explained by the SP results obtained in the present study. Further experiments have also demonstrated that NOM fractions are capable to penetrate inside NF membranes pores and can change their internal charges with a displacement of the iep of the membrane. As the size of the humic acid particles in our study is 250 nm and the average pore size of the membrane is 10 nm, it should be theoretically impossible to have fouling inside the pores. But from our SP results we checked that one portion of humic acid particles which are having particle sizes less than 10 nm (or low MW fractions) has entered into the membrane pores and changed the charge of the membrane pore walls.

Evolution of potential difference (Δϕ) as a function of transmembrane pressure (ΔP) for clean and fouled membrane; [KCl] = 10−3 M, pH = 6.7.

Fig. 11 presents the pH dependence of zeta potentials (ζ) for a 10−3 M KCl solution. It appears to be sensitive to pH shifting as expected with surfaces for which the charging process involves dissociation of ionizable (acidic or basic) surface groups. The isoelectric point (iep), i.e., the particular pH for which the net charge on the membrane surface (and so, the streaming potential) is zero, is found to be close to 2.3 for the clean membrane (value in agreement with Pontie [12]) and for the fouled membrane ∼1.5. It was found that the zeta potential of HA particles that we used to form the cake is −30 mV (see Fig. 2). In principle, the global charge of the membrane in presence of the HA cake should be higher. Even so, the obtained results show that the membrane charge decreases with the HA cake formation. These results can be explained by the fact that conductivities employed to calculate the potential is that of the solution and not conductivities in the pores, which are much higher. In addition, the size of the membrane pores was decreased by deposition of particles on the pore walls.

Zeta potentials vs pH of the solution; [KCl] = 10−3 M, clean membrane and fouled membrane.

Considering those results, we can hypothesise also that the membrane should be fouled inside the pores by positive or neutral fractions of the HA solution. Another hypothesis is that the role played by the cake should also be considered, which can also manage the membrane charges independently of the membrane itself. Further experiments have to be done to give a response to those interrogations.

Thus the new semi-automatic SP tool would help us in the future to assess the charge inside the pores caused by very low MW humic acid fractions. At the same time FESEM analysis should be engaged with pore analysis to complete such an approach.

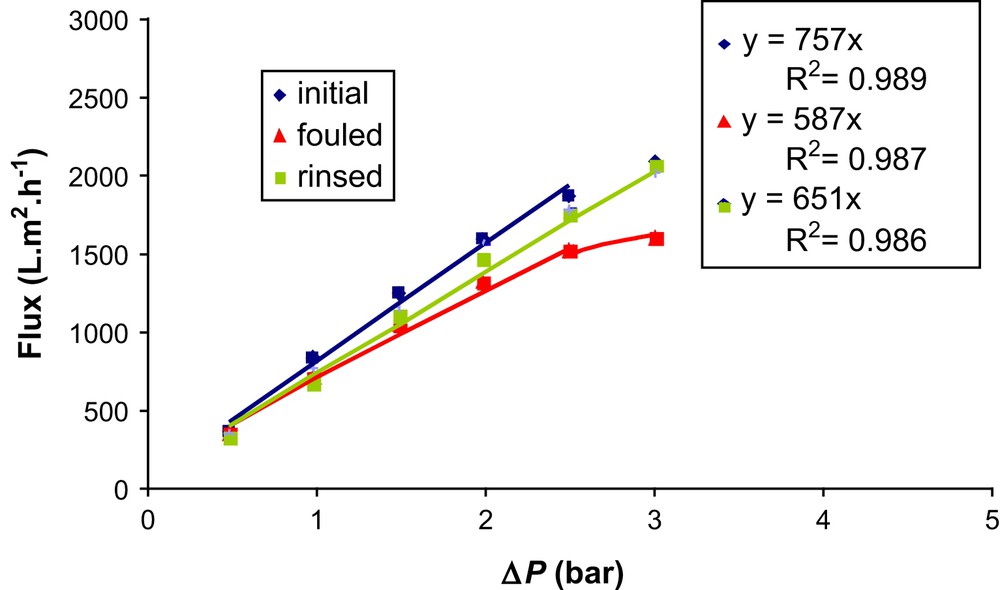

4.5 Preliminary seawater results

As indicated in Fig. 12, in the linear range of the curves, the membrane hydraulic permeability was 757 L m−2 h−1 bar−1; permeability after seawater filtration was 587 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 and the permeability after rinsing with ultrapure water during half an hour was 651 L m2 h−1 bar−1. At the same time, the SP measured, which was initially −24 mV/bar, decreased to −21 ± 1 mV/bar after fouling. The operation of rinsing had no effect. The attenuation of the charge (less negative) as deduced from the streaming potential measurements also indicates that foulants are also present in the membrane pores. This finding may indicate that fouling agents may correspond to neutral-type structures (i.e. polysaccharides) or possibly positively charged components (i.e. aminosugars) as recently reported [23].

Flux vs transmembrane pressure (ΔP) after and before seawater filtration across the RC 100 membrane.

5 Conclusion

Humic acid particles, aggregated on the RC 100 membranes and analysed by FESEM demonstrate that the fouling layer appears to have a fractal nature with a fractal dimension of FD = 2.52. Then, as a microscopic approach, fractal dimension can be used as a new parameter to describe cake layer formation that can be linked to hydraulic permeability decrease. As macroscopic tools, MFI-UF value and cake resistance value (Rc) can be used to explain cake formation mechanism. SP measurements helped to understand the charge-related modification inside the pores. These results suggest that fractal analysis should be linked to fouling layer resistance and/or modified fouling index. The novel SP apparatus would help us to distinguish pore blocking from pore clogging. Thus our main objective is to understand the way of organization of the humic acid cake and thereby to find a solution to de-organize it in order to limit membrane fouling and hence to increase the membrane's lifetime.

Our approach in future works will be to better understand the link existing between macroscopic and microscopic parameters under various operating conditions (transmembrane pressure, HA concentration and nature, ionic strength, membrane material and pore size, roughness of the membrane material), in order to limit membrane fouling for a sustainable development of low-pressure membrane processes as RO pre-treatment operations. Furthermore, we would like to better characterize the nature of the fouling material that is responsible for the hydraulic permeability decrease observed during low-pressure membrane filtration (MF or UF) of seawater.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. R. Filmon of the Microscopy Department (SCIAM) of the University of Angers, for helping us to perform the FESEM analyses and Pr. Jean Duchesne, Director of the Landscape team (INH–Angers University, France) for to fractal dimensions analysis. Lots of thanks to Malvern corp. for having helped us to determine the zeta potentials and the average sizes of the humic particles in solution.