1 Introduction

Industrial chimneys, gasoline and diesel engines emit considerable amounts of particulate matter (PM) as well as volatile organic compounds (VOC) [1]. One of the principal solutions to reduce their emissions is the catalytic oxidation technique [2,3]. Several mixed oxides systems presenting high oxygen storage capacity were investigated for their use in catalytic oxidation reactions [4–6]. However, these latter are relatively costly and they may present some environmental adverse effects. Cobalt, magnesium and aluminium mixed oxides synthesized by hydrotalcite route (HT) and used as supports for different metals are potential candidates to deal with cost and toxicity problems. They were tested in several catalytic reactions as the oxidation of carbon black (CB) [7] and VOC [8]. Moreover, supported precious metals such as Pt and Pd are well established as efficient catalysts for VOCs combustion [9] but unfortunately are very expensive and are susceptible to poisonning. On the other hand, ruthenium oxide based catalysts are cheaper and have showed good reactivity in acetic acid, propene and CO oxidation reactions and in various catalytic reactions such as: water-gas shift, ammonia synthesis and reduction of NO [2,10]. Indeed, the association of ruthenium oxide and ceria establishes a successful catalytic system in oxidation reactions [11,12]. In fact, under oxidative conditions, Ru is transformed to RuO2, showing highly desirable reactivity and stability and having a lower cost than other noble metals. However, few if any studies have been devoted to the total oxidation of volatile organic compounds and carbon black in the presence of ruthenium supported on cobalt, magnesium and aluminium mixed oxides.

In this study, Ru/CoxMgyAl2Oz solids were developed and their reactivity was evaluated in CB and propylene oxidation reactions in order to consider their use as a potential solution for some types of air pollution emissions.

2 Experimental

Four different CoxMgyAl2Oz mixed oxides supports (x and y are the numbers of cobalt and magnesium atoms respectively in one formula unit) with an atomic ratio (Co2+ + Mg2+)/Al3+ = 3 were prepared and stabilized as detailed in [7]. An adequate quantity of Ru(NO)(NO3)3 solution (1.7 wt.% Ru) was added to 1 g of the calcined supports already dispersed in 50 mL of water to obtain a nominal metallic Ru content of 1 wt.% in the final catalyst. The obtained mixture is then stirred during 2 h for maturation, and left overnight to dry in the oven at 60 °C. Catalysts were thermally stabilized by calcination at 600 °C (1 °C min−1) under air flow (2L h−1) during 4 h.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments were performed at ambient temperature on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (1.5405 Å). The diffraction patterns were indexed by comparison with the JCPDS files. Temperature programmed reduction (TPR) was carried out on a ZETON ALTAMIRA apparatus. Hydrogen (5 vol.% in Ar) was passed through a U-shaped reaction tube containing the catalyst under atmospheric pressure at 30 mL min−1. The tube was heated with an electric furnace at 5 °C min−1, and the amount of H2 consumed is monitored with a thermal conductivity detector.

The oxidation of carbon black CB (N330 Degussa: Ssp = 76 m2 g−1, elementary analysis: 97.23 wt.% C; 0.73 wt.% H; 1.16 wt.% O; 0.19 wt.% N; 0.45 wt.% S), was studied by simultaneous thermogravimetric (TG) — differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis using a Labsys Evo apparatus. Before test, 10 wt.% of CB and 90 wt.% of catalyst were manually shaken for 5 min inside a plastic tube to obtain “loose contact” conditions (L) or grinded for 10 min using a mortar and a pestle to obtain “tight contact” conditions (T). An amount of 10 mg of the mixture were then loaded in an alumina crucible and heated from room temperature up to 900 °C (5 °C min−1) under air flow of 50 mL min−1. Propylene (C3H6 6000 ppm) oxidation was carried out in a U-shaped catalytic fixed bed micro-reactor (diameter: 1 cm/catalytic bed height: 2 mm), coupled to a Varian 3600 gas chromatograph using a double flame ionization and thermal conductivity detection. An amount of 100 mg of a catalyst were used with a total gas flow (air + propylene) of 100 mL min−1 and a heating rate of 1 °C min−1.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 XRD characterization

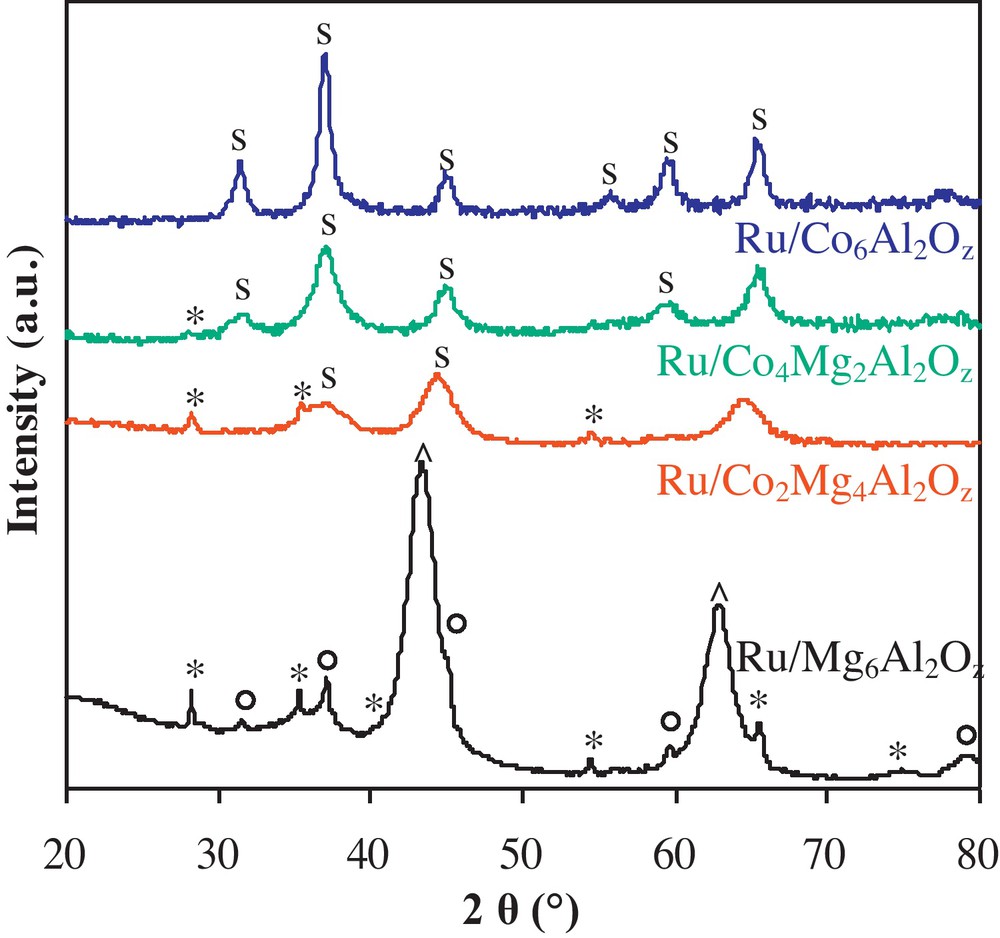

XRD patterns of freshly calcined Ru/CoxMgyAl2Oz catalysts are shown in Fig. 1. The Ru/Mg6Al2Oz catalyst pattern presents diffraction lines corresponding to the MgO periclase phase (JCPDS N°45-0946) and the MgAl2O4 mixed oxides phase (JCPDS N°73-1959). Moreover, diffraction lines characteristic of RuO2 in a tetragonal phase (JCPDS N°40-1290) are observed on the same pattern. For cobalt-containing catalysts, the patterns present diffraction lines corresponding to Co3O4 (JCPDS N°42-1467), CoAl2O4 (JCPDS N°44-0160) and Co2AlO4 (JCPDS N°38-0814) crystallized in a spinel phase. It is not possible to distinguish between these different mixed oxides using the XRD technique since they give similar patterns. It is important to note that despite the presence of the same ruthenium amount, the diffraction lines corresponding to RuO2 became less intense for the Ru/Co2Mg4Al2Oz catalyst and totally disappeared for higher cobalt contents. This result shows that ruthenium oxide species tend to form well-crystallized agglomerates when magnesium content is high. On the other hand, the presence of cobalt enhances the dispersion or ruthenium oxide species or even facilitates the incorporation of some ruthenium atoms into the spinel phase described above.

XRD patterns for Ru/CoxMgyAl2Oz catalysts. “s”: Co3O4 (JCPDS N°42-1467), CoAl2O4 (JCPDS N°44-0160) and Co2AlO4 (JCPDS N°38-0814) mixed oxides; “*”: RuO2 phase (JCPDS 40-1290); “^”: MgO periclase phase (JCPDS N°45-0946); MgAl2O4 mixed oxides (JCPDS N°73-1959).

3.2 Catalytic results

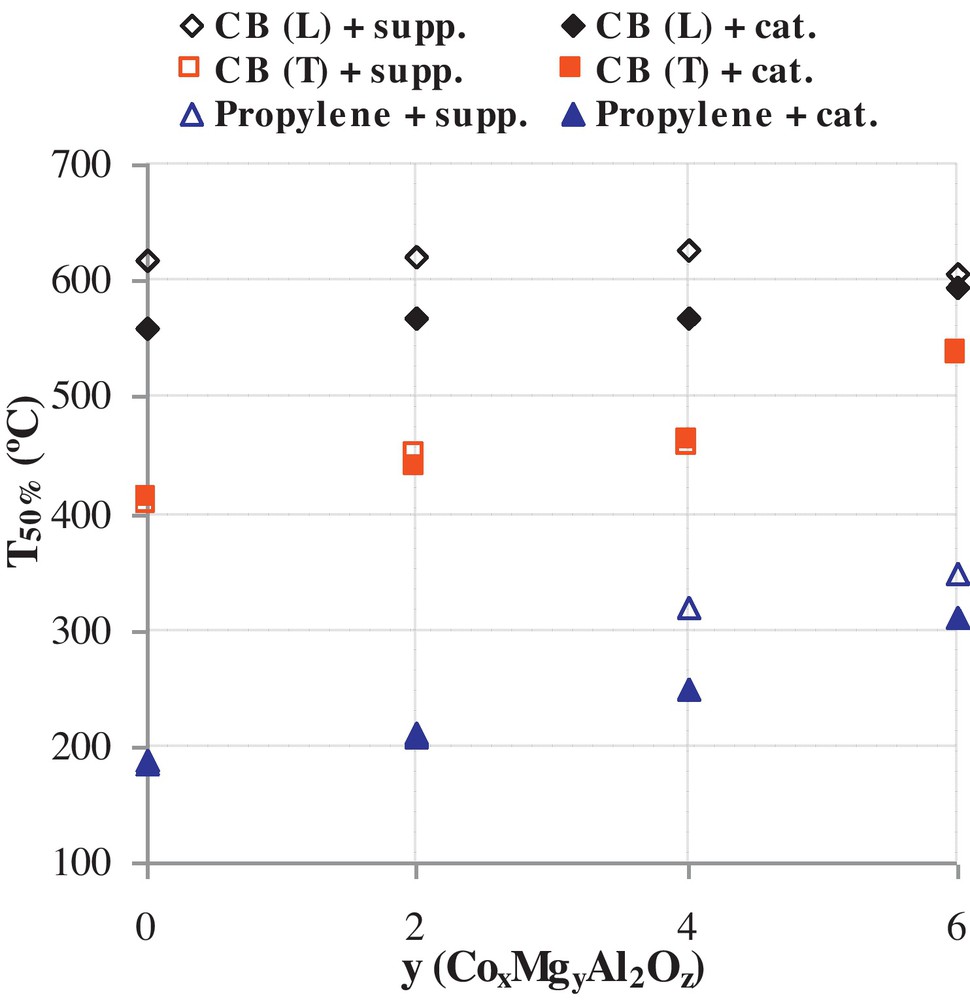

Fig. 2 shows the parameter T50% that represents the temperature at which 50% of carbon black or propylene is converted in the presence of CoxMgyAl2Oz supports or Ru/CoxMgyAl2Oz catalysts. It is observed that CoxMgyAl2Oz supports do not show significant catalytic reactivity in the CB oxidation test under “loose contact” conditions. However, the Ru/CoxMgyAl2Oz catalysts decreased T50% under the same contact conditions. For example, a substantial 70 °C decrease from 629 °C (without any catalyst) down to 559 °C for Ru/Co6Al2Oz was observed. This can be explained by a “spill over” mechanism of O2 over Ru oxide species. In fact the dissociative adsorption of oxygen over metallic ruthenium is low (≈10−6), but when a very small quantity of RuO2 is formed on the surface, the reaction of oxide formation is self catalyzed because the dissociative adsorption coefficient of oxygen over ruthenium oxide is high (0.7) [13]. Moreover, in loose contact, the mobility of ruthenium oxide species plays a major role knowing that the Tamman temperature of RuO2 is close to the observed temperature range in the carbon black oxidation under “loose contact”. In addition, a decrease of T50% is observed when the amount of cobalt is increased. Under “tight contact” conditions, it is clearly observed that all prepared solids are significantly reactive in the total oxidation of CB and that T50% are much lower than those obtained for “loose contact” conditions. This is due to the grinding that decreased the aggregates sizes, increasing the number of contact points between catalytic sites and CB. Moreover, it appears that ruthenium addition did not contribute significantly to the catalytic reactivity under “tight contact” conditions. In fact, the grinding leads to several direct contact points between cobalt oxide species and carbon particulates, which makes the oxidation of these latter possible at lower temperatures and making the promoting effect of ruthenium less important. Thus, the presence of ruthenium can be considered as a precursor for the initiation of CB oxidation at low temperature and for “loose contact” conditions. Once the reaction is initiated, cobalt oxides take over to complete the redox cycle. In order to evaluate the contribution of the best catalyst (Ru/Co6Al2Oz), the activation energy (Ea) and the Arrhenius parameter (A) were calculated based on the method described in [14]. In this method, the required data are directly retrieved from TG curves and used in the below equation:

Effect of the support composition on T50% for the carbon black and propylene oxidation reactions over CoxMgyAl2Oz and Ru/CoxMgyAl2Oz solids.

Activation energies and Arrhenius pre-exponential factor for the non-catalyzed and catalyzed CB oxidation.

| Reaction | Ea (kJ mol−1) | lnA |

| Al2O3 + CB | 151 | 18.5 |

| Ru/Co6Al2 + CB (L) | 138 | 17.3 |

| Ru/Co6Al2 + CB (T) | 111 | 17 |

Concerning propylene oxidation, it is to be noted that total conversion is not achieved before 690 °C [12]. The support that showed the best reactivity in total propylene oxidation is Co6Al2Oz with a T50% = 182 °C (Fig. 2) compared to ∼550 °C for the non-catalyzed reaction [12]. Compared to the other supports, Mg6Al2Oz presents the lowest reactivity. For supports with high cobalt contents, (x = 4 and x = 6), the addition of ruthenium did not significantly enhance the catalytic reactivity. However, for lower cobalt contents (x = 2 and x = 0), ruthenium addition contributed to lower T50% (Fig. 2). This can be explained by the fact that the weight percentage of ruthenium is small compared to that of cobalt for high x values and therefore its contribution is negligible compared to that of cobalt. While, for low x values, the catalytic reactivity of ruthenium oxides becomes important compared to less reactive cobalt oxide species (on an atom to atom basis) and therefore T50% values were decreased. It is worth mentioning that the selectivities towards CO and CO2 were monitored in both CB and propylene oxidation reactions and were found to be equal to 0% and 100%, respectively, whatever the catalyst used.

The catalytic behavior of the different solids may be partially explained by the XRD results presented at the beginning of this section. In fact, catalysts with high cobalt content showed the best reactivity owing to the good dispersion of ruthenium oxide species, which initiate the different reactions. However, the contribution of the support composition to the catalytic reactivity is difficult to elaborate using the XRD results.

3.3 TPR Results

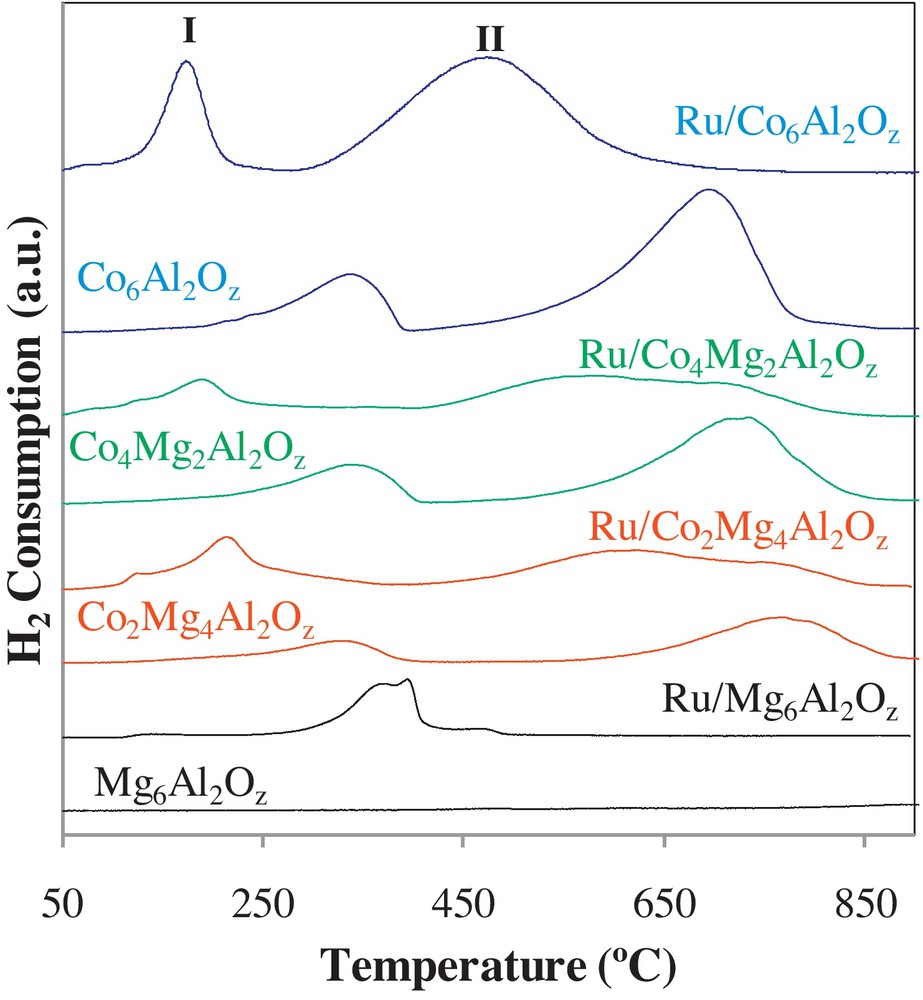

In order to gain more insight in the catalytic process-taking place during the reactions, a TPR study was done on the different calcined solids. Fig. 3 shows TPR profiles of calcined CoxMgyAl2Oz supports and Ru/CoxMgyAl2Oz catalysts. Mg6Al2 does not show any reduction peak due to the non-reducibility of magnesium oxides species in the studied temperature range. Cobalt containing supports present two reduction peaks. The first peak (I) is situated in the 270 °C to 370 °C range while the second peak (II) appears in the 600 °C to 850 °C range. These two peaks are attributed to the reduction of Co3O4 and Co-Al mixed oxides species, respectively. The area of those peaks increases with the increase of Co content. The maximum temperature of peak II is shifted towards lower temperatures when the amount of cobalt increases due to kinetic considerations that suggest that the reduction temperature decreases when the amount of reactive sites increases. The Ru/Mg6Al2Oz solid showed one composite reduction peak attributed to the reduction of RuOx species with different cluster sizes. Cobalt-containing catalysts showed two reduction peaks. The first peak (I) in the 150 °C to 230 °C temperature range is attributed to simultaneous reduction of ruthenium and cobalt oxide species. The second peak (II) in the 280 °C to 420 °C temperature range corresponds to the reduction of Co–Al mixed oxides species that behave similarly to CoAl2 O4 spinel [17] that will be reduced into Co(0). The modification of the supports with ruthenium shifted the Co oxides species reduction peaks to lower temperatures. This shift affected both reduction peaks, (I) and (II), observed for calcined supports. This decrease is greater for higher cobalt contents showing the formation of a greater amount of easily reducible species in the presence of ruthenium. The TPR results make it clear that the oxidation reduction behavior of the solids is responsible for the catalytic reactivity in the oxidation reactions. In fact, for higher cobalt contents, more easily reducible species are present and participate in the catalytic process. The addition of ruthenium made the reduction of those species possible at even lower temperatures, which allowed the earlier initiation of the oxidation reactions.

H2-TPR profiles for the different CoxMgyAl2Oz supports and Ru/CoxMgyAl2Oz catalysts.

4 Conclusion

CoxMgyAl2Oz mixed oxides are cheap and reactive in carbon black (tight contact) and propylene oxidation reactions. However, under real conditions, the contact between soot and the catalyst is more represented by the “loose contact” mixing. To promote the reactivity of these supports under “loose contact” conditions, the addition of a small amount of ruthenium (1 wt.%) can be considered. The presence of ruthenium oxide species initiates the oxidation reaction at lower temperatures especially when cobalt content is low.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research for financial support, contract 02-11-09.

The authors would like to thank the BRG 4/2010 for financial support.