1 Introduction

Life would not exist without oxidation! Oxidation is extremely important, both from a scientific and a practical point of view [1–15]. In the chemical industry, the oxidation reaction is probably the most important process, playing a key role in numerous industrial, environmental and energy applications [16–32].

Most monomers and ∼25% of all catalytic reactions are obtained by heterogeneous oxidation of hydrocarbons mainly over metal oxide catalysts, and even ∼50% of bulk chemicals if one includes synthesis of NO (NH3 oxidation over a Pt-based catalyst) and SO3 (oxidation of SO2 over a V-based catalyst). For instance, C2–C8 hydrocarbons lead to monomers such as vinyl chloride, ethene oxide, acrolein, acrylic acid, acrylonitrile, methacrylic acid and methacrylates, maleic and phthalic anhydrides, etc. The majority of studies have focussed on olefin-selective oxidation, in particular propene to acrolein over bismuth molybdate-based catalysts and acrolein to acrylic acid/acrylonitrile over Bi and V molybdate-based catalysts by the SOHIO group as early as the 1960s [33], but also on light alkanes, such as C2-, C3- or C4-activation by oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH) to olefins (C2= to C4=), or carboxylic acids on different oxides, such as Bi molybdates or vanadates, metal ions exchanging heteropolyacids of the Keggin-type, etc. Direct alkane selective oxidation has drawn major interest in industry and academia [16,34–41]. For instance, direct oxidation of propane to acrylic acid/acrylonitrile on MoNbSb(Te)V–O, of butane to maleic anhydride on VPO catalysts, of isobutyric acid oxidative dehydrogenation to methacrylic acid on Fe hydroxyl-oxy-phosphates, etc., has led to industrial processes.

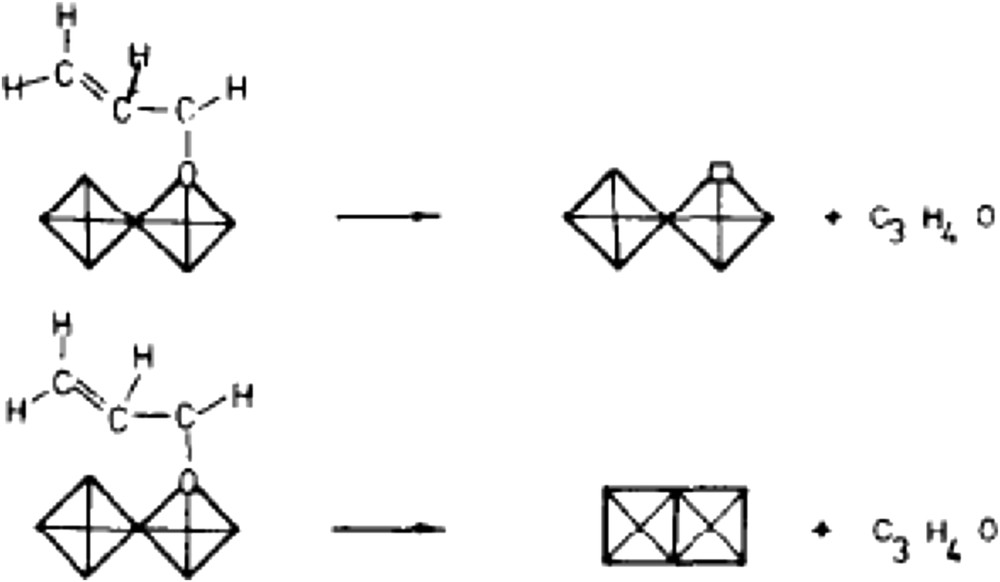

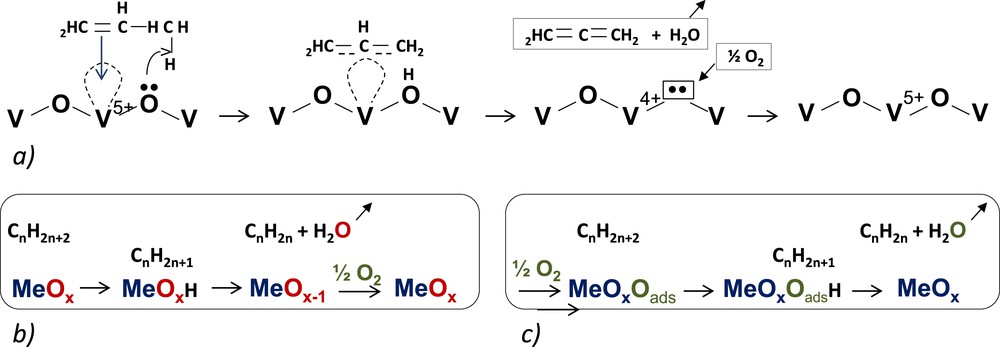

The activities in the area of oxidative dehydrogenation of alkanes started in the 1960s [42]. In 1961, the oxidative dehydrogenation of pentane and 2-methylbutane was reported and mentioned the importance of the nature of surfaces on conversion and selectivity [43]. Another example was reported on the use of cobalt molybdate to enhance the formation of butadiene from a mixture of butane and oxygen rather than from simple dehydrogenation [44]. A Sb-Mo oxide catalyst was reported to oxidise 2-methylpropane to methacrolein with 49% selectivity at 22% conversion, and propane to acrolein with 29% selectivity at 15% conversion using a mixture of alkane, air, ammonia, and water at 508 °C [45]. The new technology of catalytic oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH) may completely change the way some of the nation's most important organic chemicals are manufactured. The conversion of alkanes like ethane (a by-product of petroleum processing and present in natural gas) to olefins (ethene, propene, butenes, and butadiene) is in great demand in the domestic and worldwide chemical industry. The lower price of light alkanes in comparison to the corresponding olefins makes the dehydrogenation of lower alkanes an attractive industrial process. Alkenes are important feedstock for the petrochemical industry. The demand for olefins, especially ethene, is expected to increase significantly in the near future. Selectivity and atom efficiency are the key parameters for all of the chemical reactions [46–56]. A high selectivity is necessary for achieving a high efficiency in the use of raw materials, environement and energy [57–64]. The selective transformation by oxidative catalytic processes such as oxyhydrogenation of low molecular weight alkanes into more valuable products such as olefins or unsaturated oxygenates with adequate catalysts is still a challenging task due to the low intrinsic chemical reactivity of the alkanes which demands a high energy input to activate them. Dehydrogenation of alkanes to light olefins shows some major disadvantages, i.e., a high tendency to coking and consequently a short catalyst lifetime [65]. Transformations of hydrocarbons promoted by solid metals and their oxides play very important roles in the chemical industry with oil fractions, oxidation, dehydrogenation, isomerisation and many other processes of saturated as well as alkylaromatic hydrocarbons [66–84]. Metal oxides represent the most important families of solid catalysts for selective heterogeneous oxidation catalysis as active phases or as supports. The three main features of these oxides, which are essential for their application in catalysis, are: i) the coordination environment of the surface atoms; ii) the redox and, subsequently, acid–base properties; and iii) the oxidation states of the surface cations. A general feature of the selective oxidation reactions in heterogeneous catalysis which has appeared with the years is that the oxide surface could be considered as living, as in a breathing motion, to allow the Mars and van Krevelen mechanism to occur. This consideration of the oxide surface was inspired by the suggestion of Haber [85–87] shown in Fig. 1. Such a property was clearly shown for iron phosphate catalysts used for isobutyric acid dehydrogenation to methacrylic acid (vide infra), implying that the oxide structure should be strong enough to allow the redox mechanism to occur without structural collapse such as , as schematised in Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the mechanism of O insertion into a hydrocarbon molecule and its consequences in the creation of a reversible O vacancy in a metal oxide (right part) [86,87].

The surface of the oxide may well be badly crystallised, i.e., amorphous in the sense of XRD, to facilitate the occurrence of the redox mechanism, although the surface should also reflect the underlying crystallised structure as shown, for example, for V2O5/TiO2 catalysts by HR-TEM analysis [88], and for VPO catalysts in n-butane oxidation to maleic anhydride [89]. An oxide surface could be badly organised although the underlying bulk structure is well defined. Seven key factors, designated as pillars by Grasselli [90], have been proposed to be satisfied for selective oxidation reactions to occur, namely: i) nature of lattice oxygen anions: nucleophilic (selective) rather than electrophilic (total oxidation); ii) redox properties of the metal oxide (removal of lattice oxygen and its rapid reinsertion); iii) host structure (permits the redox mechanism to occur without collapsing); iv) phase cooperation in a multicomponent catalyst or supported catalyst (epitaxial growth and synergetic effects); v) multifunctionality (e.g., α-H abstraction and O-/NH- insertion); vi) active site isolation (to avoid too high lattice O surface mobility and thus overoxidation); vii) M–O bond strength (not to be too weak (total oxidation) nor too strong (inactivity) (Sabatier principle)). Point i) of the active oxygen species was discussed a long time ago in two review articles by Tench and Che [91] who have described different types of oxygen species. For the redox mechanism, one may write: ; . These oxygen species are more or less electrophilic, or nucleophilic in the nomenclature proposed by Haber [92].

2 Structural aspects of MxOy oxides

Structural properties of MxOy oxides confer specific selectivity in oxidation reactions that depend on redox couples Mn+/M(n−p)+, length/strength/ energy of M−O bonds, anionic defects (vacancies or anion excess, in particular O2−) and/or cationic (vacancies or cation excess) [93]. The surface and bulk mobility of oxygen species is also an important characteristic of the catalyst. Selective oxidation catalysts generally contain a transition metal cation such as Ti, V, Cr, Mo, and W, highly charged, small and polarising. In vanadyl (VO2+) and molybdenyl (MoO22+) oxo-cations, multiple bonds are formed between the cation and oxygen. V5+ cations (ionic radius of ri = 0.054 nm) float in an octahedral environment of six O2– (ri = 0.140 nm) and forms a VO bond to be more stable. The V⋯O bond in trans VO is longer, and its binding energy is weaker. Thus, this oxygen may easily be withdrawn, and the V coordination becomes five. Another striking feature is that octahedral environments of VO6 in V2O5 and in V2O4 are very similar. Compared to V5+, OV4+ and V4+⋯O bonds are longer (from 1.58 to 1.64 nm) and shorter (from 2.78 to 2.70 nm), and the height of the octahedron changes very little. Therefore, at the first approximation, one may expect an easy e– transfer: V5+ ↔ V4+ or Mo6+ ↔ Mo5+ couples (ri = 0.059 nm et 0.061 nm for Mo6+ and Mo5+) and thus improved catalytic properties. As a matter of fact, a catalyst will be more active as its structural changes are small.

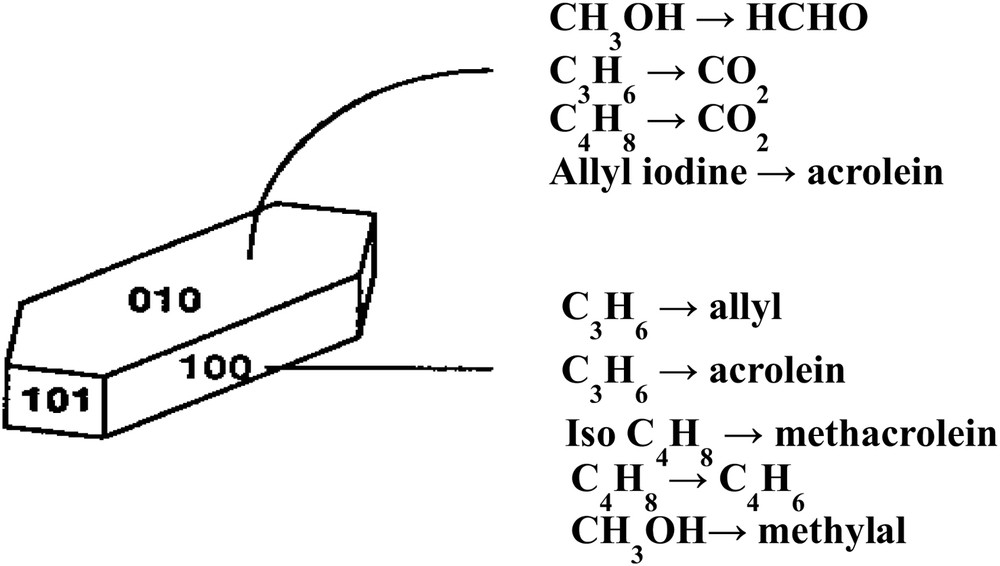

Structural sensitivity of metal oxides for oxidation reactions was demonstrated for the first time by Volta [94] for propene partial oxidation when using a novel method to prepare MoO3 crystals with specific orientations. The method consisted in oxy-hydrolysing MoCl5 intercalated between layers of graphite. It was shown that propene gives almost exclusively acrolein on the (100) lateral face and CO2 on the apical (10-1), (101) and basal (010) faces (Fig. 2). For the oxidation of but-1-ene to 1-3 butadiene or the oxidation of isobutene, the selectivities observed, as a function of the surface faces exposed, were completely different (010) for 1-3 butadiene from but-1-ene, (100) for methacrolein CH2C(CH3)–CHO and COx from isobutene CH2C(CH3)2, etc., demonstrating how the geometry of the reacting molecule and atomic arrangements at the oxide surface is important in partial oxidation reactions [95]. This is schematized in Fig. 2. A more general view on butene selective oxidation on large crystals of MoO3 was published later on by Tatibouët et al. [96]. The role of the (100) face was also observed by Gaigneaux et al. [97] for the oxidation of isobutene to methacrolein at 420 °C on MoO3 and MoO3 doped with Sb2O4. In the later case, Sb2O4 was shown to favour the formation of the (100) face on the surface of MoO3 and then to enhance the methacrolein formation.

Structural sensitivity of selective oxidation reactions of olefins or methanol on single crystals of MoO3 as plates (mainly (010) faces). Assignment of reactions to surfaces as indications obtained from comparison of many sample shapes [98].

The same type of structural sensitivity was observed subsequently by Germain and Tatibouët [99,100] for MoO3 in the alcohol oxidation of methanol to formaldehyde and ethanol to acetaldehyde. However, in this case, the basal (010) face was observed to be selective for the aldehyde formation. A review article has summarised these findings [96]. Subsequently, many selective oxidation reactions, such as n-butane to maleic anhydride on the (100) face of (VO)2P2O7, or propane to acrylic acid on the M1 phase (MoVTeNb–O), etc. (vide infra), have been shown to be structure-sensitive.

3 General reaction mechanisms

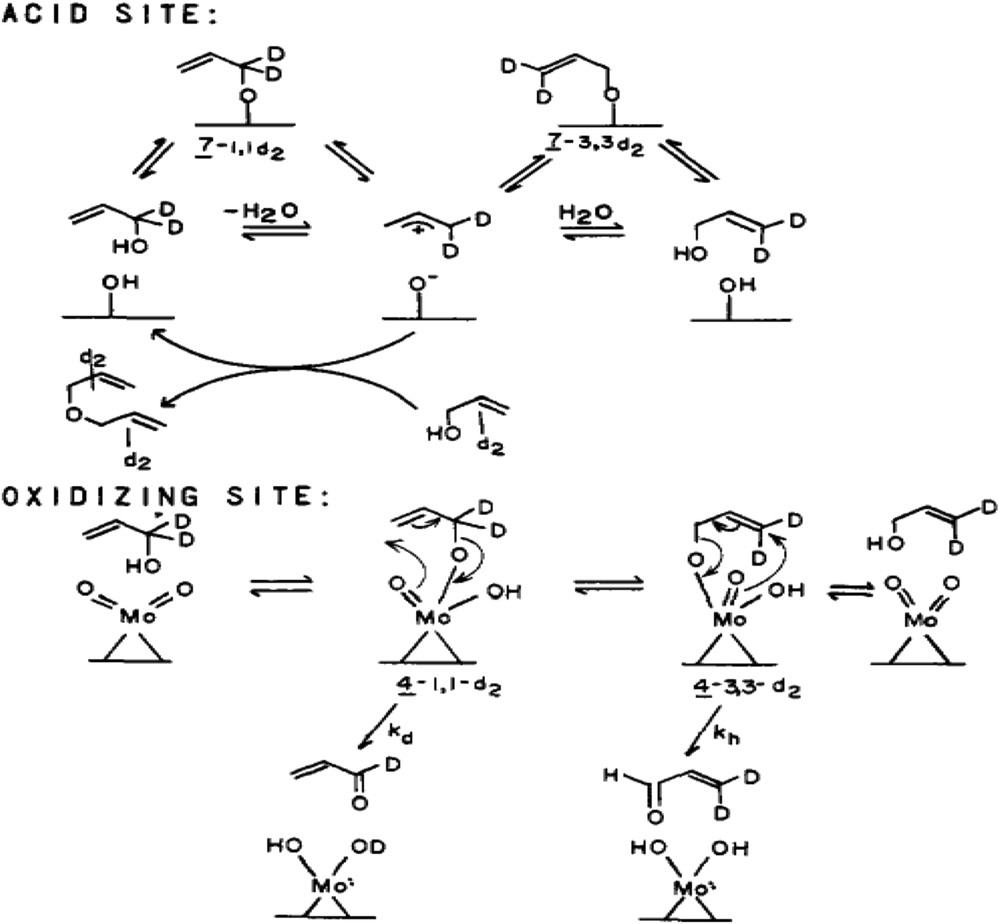

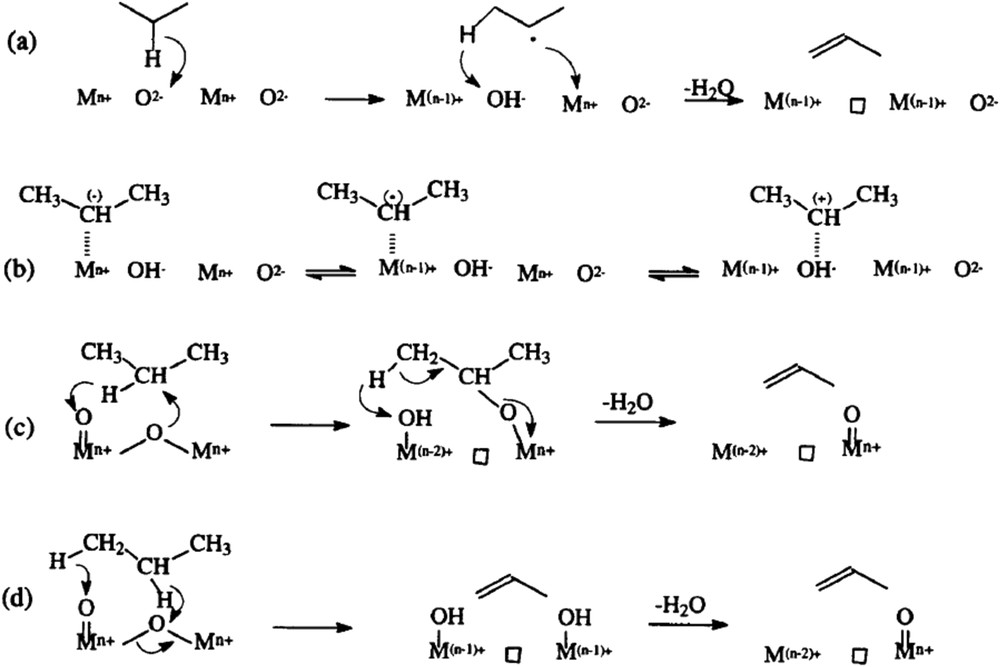

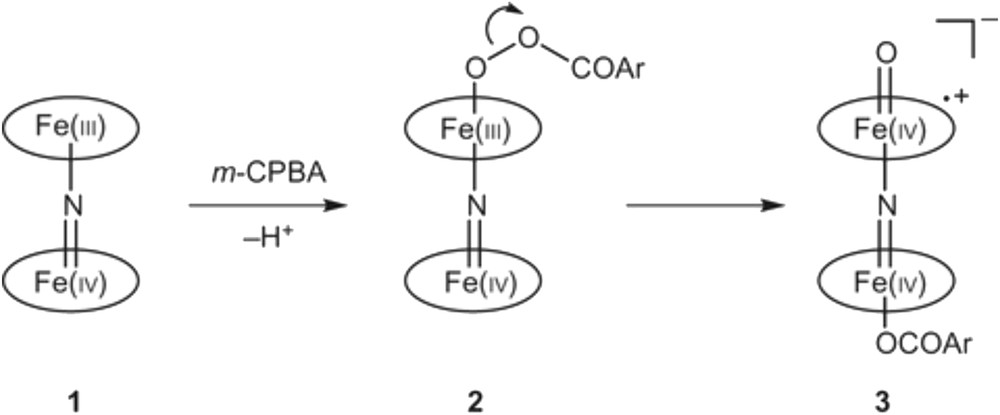

Many oxidation reaction mechanisms have been proposed in the literature [33,34], since the pioneering work from Sohio scientists for propene ammoxidation to acrolein/acrylonitrile on bismuth molybdate-based multicomponent catalysts (Bi2MO3O12/Co, FeMoO4) in the 1960s [33]. Propene chemisorption was suggested to occur on Mo centres, and the rate determining step was suggested to be the α-H atom abstraction by Bi–O, leading to a radical-like α-allyl Mo complex. O or N insertion centres consist of coordinately unsaturated OMoVlO or HNMoVINH sites, respectively. The reversible formation of the α-O or N-allyl molybdenum complex occurs prior to subsequent (i.e., 2nd and 3rd) allylic H abstractions as schematised in Fig. 3 for propene oxidation. The presence of Bi facilitates the second H-abstraction, which has a lower Ea for oxidation than for ammoxidation. Alternative routes of propane conversion to propene depending on the acid–base properties of an oxide surface are also presented in Fig. 4 [101,102].

Reactions of allyl-1,1-d2-alcohol at acid and oxidising sites [33b].

Alternative routes of propane conversion to propene depending on the acid–base properties of an oxide surface [101,102].

Differentiation of acid and redox sites in the reaction mechanism is schematised in Fig. 3:

- allyl-1,1-d2 alcohol at acid and oxidising sites.

For a selective oxidation reaction, the main reaction mechanism is the Mars and van Krevelen mechanism [103], schematised below, which involves cations in various oxidation states, such as Cr, Cu, Fe, Mo, V, etc.

| 2[CatO] + R-CH → 2[Cat] + R-C-O + H2O |

| 2[Cat] + O2 (gas) → 2[CatO] |

Simplified schemes of: a) propene adsorption O−V−O and formation of a π-allyl complex intermediate; b) case of an alkane; c) effect of adsorbed oxygen.

The MvK model is the most suitable for describing the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane [34,103] over different supported vanadium oxide catalysts, although the MvK model has also been considered inconsistent and incorrect for general reduction−oxidation reactions on solid catalysts.

4 Nature of active sites in selective oxidation reactions with heterogeneous catalysis

Vanadium supported on silica has been studied with the idea that V dispersion could be enhanced and more easily controlled. For instance, V deposited on mesoporous silica has been studied [104] and led to the most productive catalysts known for methane oxidation to formaldehyde. The higher activity was assigned to a larger quantity of the most active species, namely, the monomeric vanadium species. The higher selectivity was attributed to the high dispersion of the vanadium (because isolated monomeric species appear to be more selective than the others) as well as to a higher concentration of the isolated species. These species contain one VO bond and three bridging V–O–Si bonds or one hydroxyl group and two bridging V–O–Si bonds. The active and selective catalysts are also characterised by a higher concentration of silanol groups at their surface. This latter species may take part directly in the redox reaction mechanism, facilitating regeneration of the active and selective sites, or in the activation of methane. Although the intrinsic properties of the catalysts appear to be crucial for obtaining selective catalysis, the degradation of formaldehyde under the catalytic test conditions is an important parameter as well. Using low contact times and adding water to the gas feed allowed significant reduction of this degradation and optimised the catalyst productivity.

In 1925, in a landmark contribution to catalytic theory, Taylor [105] suggested that a catalysed chemical reaction is not catalysed over the entire solid surface of the catalyst but only at certain ‘active sites’ or centres. He also suggested that chemisorption may be an activated process and may occur slowly. Moreover, he conceived the idea that chemically active sites might be composed of an atom or an ensemble of atoms and could be sparse on the surface of a catalyst and, hence, could be inhibited/poisoned with relatively few molecules. Since that time, many descriptions of active sites have been proposed, in particular for metal oxides [106].

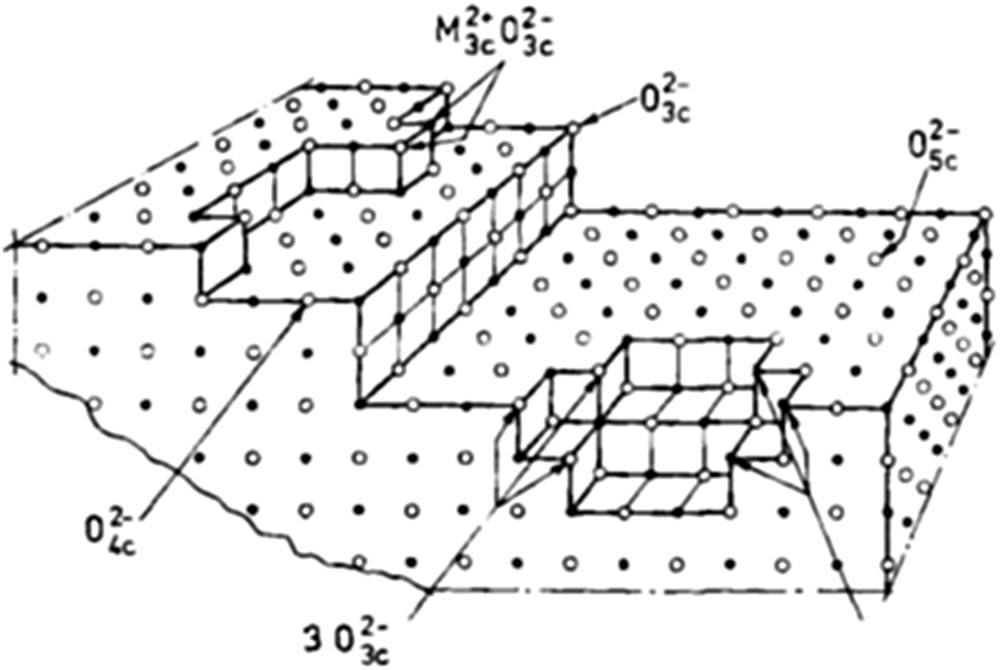

For single oxides, e.g., MgO, surface sites could be Mg2+ or O2− ions with different coordinations depending on the defective surface structure as schematised in Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the MgO surface [107,108].

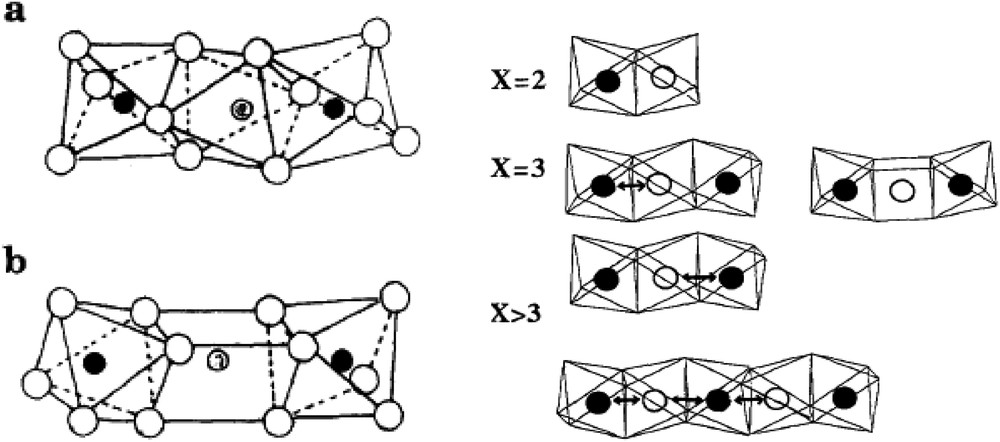

For the more complex metal oxides used industrially, the active sites are usually ensembles of atoms that should be isolated from each other to avoid overoxidation due to mobility of lattice oxygen ions. For instance, in the case of iron hydroxyphosphates, such as , used for oxidative dehydrogenation of isobutyric acid to methacrylic acid, the best active and selective sites have been described [109–111] as ensembles of FeO6 octahedral trimers in αFe3P2O7, where electron transfer during the redox process occurs between Fe2+ and Fe3+ in αFe3P2O7 but not in βFe3P2O7, as shown in Fig. 7.

Arrangements of FeO6 octhedra in trimeric clusters isolated from the others by P2O7 groups: a) αP2O7; b) βFe3P2O7; grey circles: Fe2+, filled: Fe3+. Electron exchange between iron cations in FeO6 octahedral clusters calculated by extended Hückel molecular orbital theory [112,113].

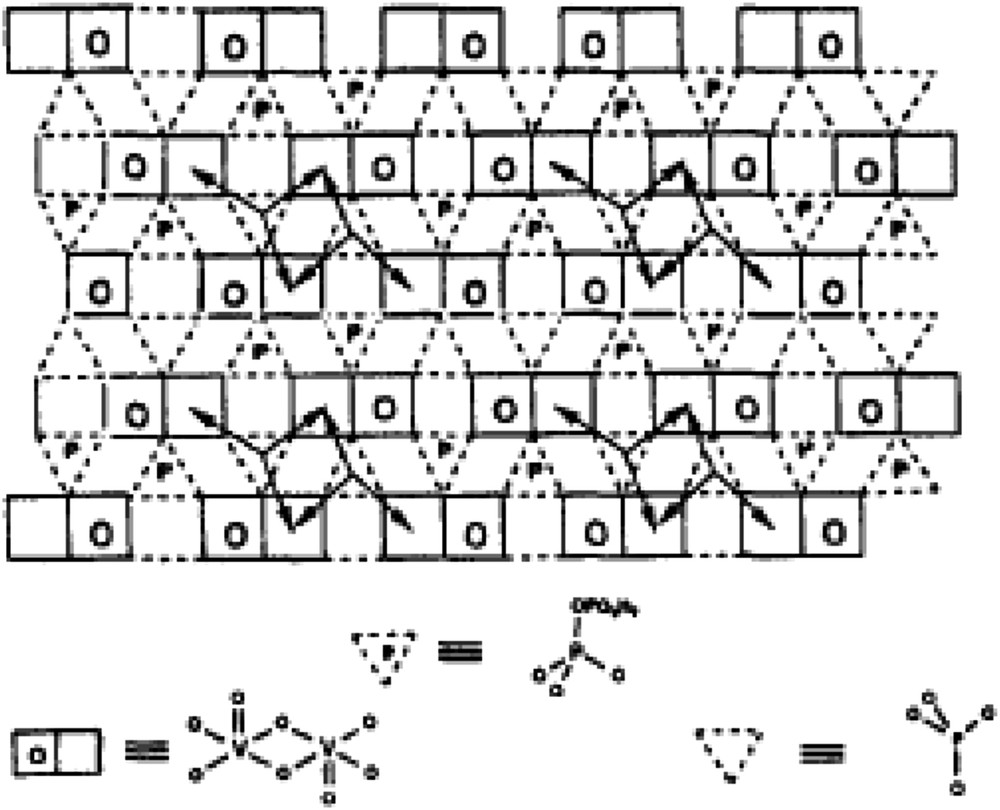

Another example corresponds to (VO)2P2O7, designated as the VPO catalyst, used industrially for butane oxidation to maleic anhydride. The active sites have been described as ensembles of four dimers of octahedral VO6 entities isolated by P2O7 groups as schematised in Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of the surface structure of a type of polytype of (VO)2P2O7. The arrows represent the facile pathways for surface oxygen mobility. This surface structure illustrates the site isolation principle by surface P2O7 groups that constitute a barrier to oxygen diffusion [114].

Several active sites are observed in the direct oxidation of benzene to phenol by N2O [6,9,115]. Panov et al., in their study of direct oxidation of benzene to phenol by N2O on Fe-MFI catalysts, have shown that active sites are FeO dimers [115] inside the pores of the zeolite. Janas et al. [116,117] have studied Co(II) ions in SiBEA zeolite. At a low Co content (0.8 wt.%), the cobalt is present as a lattice tetrahedral Co(II) species. For much higher Co content (11 wt.%), mainly extra-lattice octahedral Co(II) species and/or cobalt oxides are present as shown by DR UV–vis spectroscopy. The authors then concluded that zeolites with isolated tetrahedral Co(II) species are active in selective catalytic reduction of NO by ethanol with selectivity towards N2 exceeding 85% for NO conversion from 30 to 70%. At variance, when extra-lattice octahedral Co(II) species and/or cobalt oxides are present, the full oxidation of ethanol and NO by O2 to CO2 and NO2, respectively, was observed to be the main reaction pathway. Isolated Co(II) cations in the lattice positions were thus suggested to be the active site for the reaction.

In the past 15 years, a tremendous amount of work has been performed and published on a complex mixed oxide based on the ability of MoVTe(Sb)Nb–O to ammoxidise propane directly to acrylic acid/acrylonitrile in the presence of water vapour (Fig. 9). The highest acylonitrile yield was found for V0.3Te0.23Nb0.12MoOx supported on silica after calcination under nitrogen at 620 °C [118]. This catalyst family was discovered by researchers at Union Carbide who published their work in 1978 [119]. The best catalysts were observed to be the designated M1 phase often associated with another phase designated as M2. The researchers suggested [120] that the reaction needs either four monomeric or two dimeric units of redox storage to address one molecule of oxygen, according to:

| 4V+4–OH + 4OH− → 4V+5O + 4e− + 4H2O |

| O2 + 2H2O + 4e− → 4OH− |

| 4V+4–OH + O2 → 4V+5O + 2H2O |

| OV–O–VO + C3H6 → OV–O–V–OC3H5 + H++e− |

| OV–O–VOC3H5 + H+ +e− → HO–V–O–V–OC3H5 |

| HO–V–O–V–OC3H5 + 3OH− → HO–V–O–V–OC3H4O + 2H2O + 3e−. |

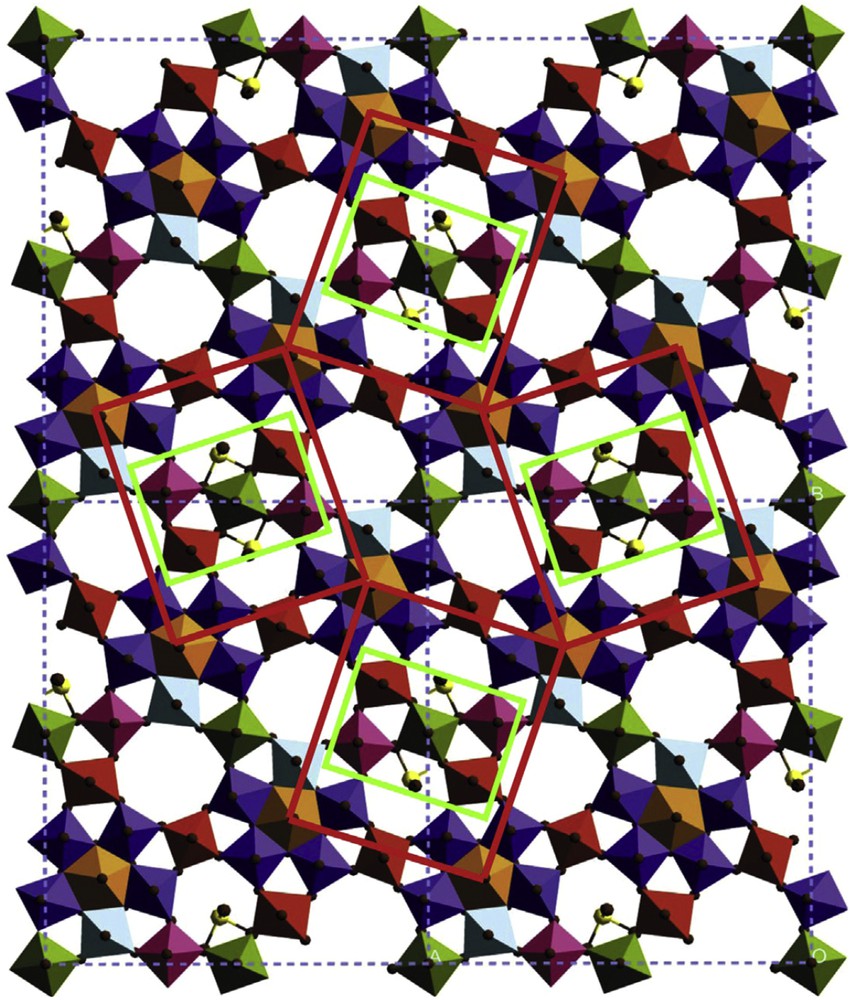

Scheme of the propane oxidation reaction (left) and structure of the M1 phase (right). Site isolation in Mo7.8V1.2NbTe0.94O28.9(M1): 2 × 2 unit cell structure model of M1 in [001] projection showing four isolated catalytically active centres. The individual active centres are site isolated from each other by four Nb-bipyramids that are surrounded by five Mo-octahedra [121].

This oxidation step leads to electronically stabilised acrolein that is still held to the active site, as the electrons released from the organic substrate do not reduce the vanadium centre. Active sites were also suggested to be ensembles of atoms as schematised in Fig. 10.

Model for active sites terminating the M1 phase surface [119].

Such an ensemble of atoms as active sites has also been proposed for enzymatic oxidation/hydroxylation reactions, using the cytochrome P-450 enzyme [122] and porphyrin-like complexes such as the N-bridged di-iron oxophthalocyanine associating cytochrome P-450 and a monooxygenase enzyme (Fig. 11) and using H2O2 [123], and is able to oxidise methane [124] into formic acid and secondarily to formaldehyde and methanol under specific conditions (40 °C, 3.2 MPa, CH3CN as the solvent), while the monomeric Fe complexes were found inactive.

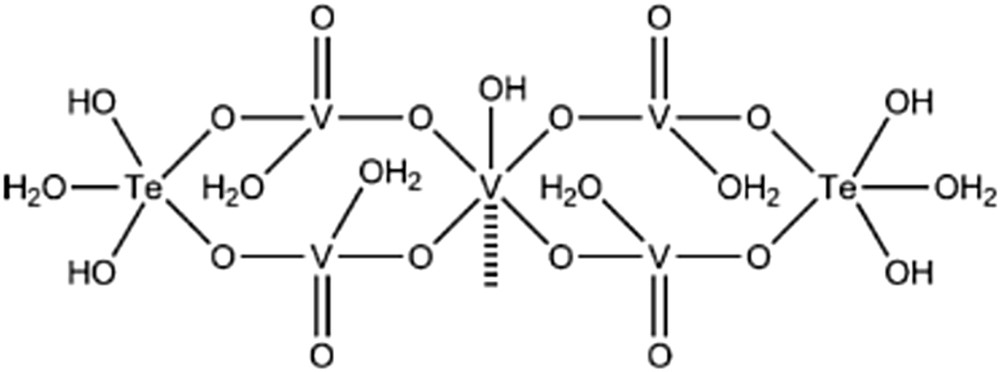

Proposed mechanism for the formation of N-bridged high-valence diiron–oxo porphyrin cation radical complex 3, which involves two key steps: (1) coordination of the peroxyacid to one iron site to form the peroxy complex 2 and (2) the heterolytic cleavage of the O–O bond to provide the high-valence diiron–oxo species 3. The presence of ArCOO2 as an axial ligand in 3 was deduced from Mössbauer data. The oval represents the tetraphenylporphyrin ligand. Ar = meta-chlorobenzene residue [124].

5 General aspects of the role of acid–base properties

Metal oxides are composed of redox metal cations and lattice oxygen anions that are Lewis acid and basic sites, respectively. The acid–base characteristics of the oxide have three major effects, namely, on reactant molecule activation, on the rates of competitive pathways of transformation and on the rate of adsorption and desorption of reactants and products. During a reaction, an acid surface is known [102,125] to favour desorption of an acid intermediate while a basic surface would favour desorption of a basic intermediate, which then would avoid further over-oxidation of the adsorbed intermediate to CO2. Thus, acidic products such as carboxylic acids should favourably be formed on acid surfaces while basic products such as olefins in ODH should favourably be formed on basic surfaces. The presence and strength of Lewis acid sites (cations) and of basic sites (O2− or OH−) are therefore important and should be determined carefully. For such characterisation [126], one usually uses FTIR or microcalorimetry of adsorbed probe molecules (base NH3 and pyridine or acid CO2 and SO2) or test reactions such as isopropanol conversion that gives propene by dehydration on acid sites or acetone by dehydrogenation on basic sites in the absence of air in the feed or on redox sites in the presence of air.

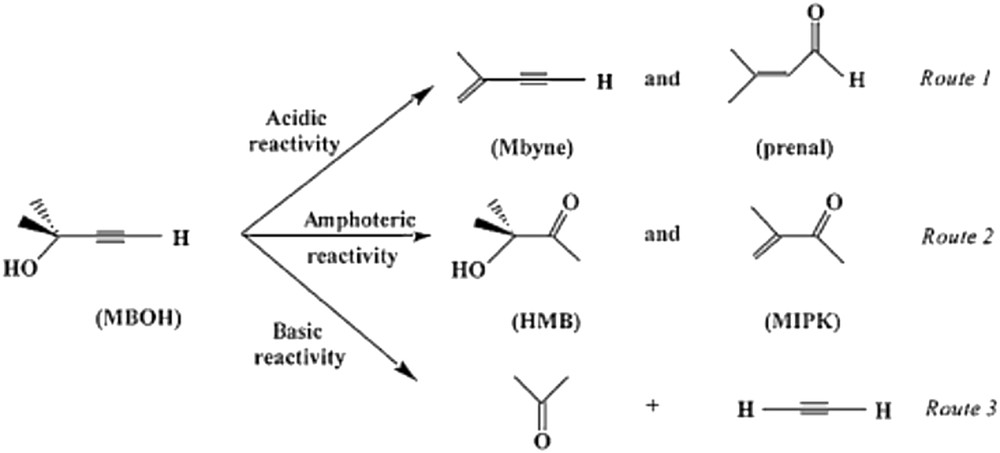

Another reaction has been proposed, namely 2-methyl but-3-en-1-yn-2-ol (MBOH) conversion [127], which follows three different pathways depending on the acid–base properties of the catalyst, as schematized in Fig. 12.

Scheme of 2-methyl but-3-en-1-yn-2-ol (MBOH) reaction pathways over an acid–base catalyst [127].

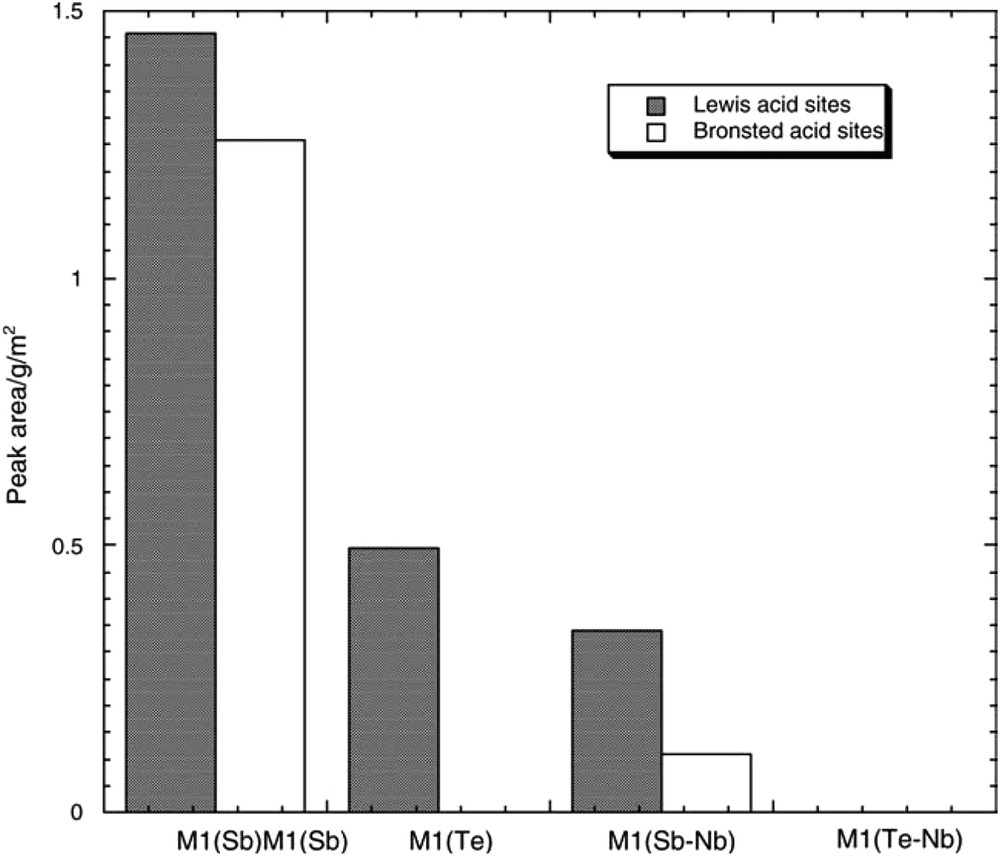

Elemental oxygen has a highly electronegative character, and its bond with metals is ionic but more basic and covalent with non-metals, therefore less basic. The electronegativity of a cation depends on its oxidation state and increases as the oxidation state increases. Oxides of metals in a high oxidation state such as V5+ or Mo6+, are characterised by a covalent metal to oxygen bond and behave as acid oxides, whereas the same elements in a lower oxidation state have a more ionic character and behave more as basic oxides. Note that metal cations, active for oxidation reactions, have several oxidation states and are able to change their oxidation state easily and thus their acid base character under certain catalytic reaction conditions. Acid strength and nature are important parameters as they are expected to participate in the alkane molecule activation by the first H abstraction. This reaction has rarely been studied. The most commonly used technique consists of studying ammonia or pyridine adsorption in FTIR spectroscopy and sometimes by ammonia temperature-programmed desorption or microcalorimetry adsorption [116,117,128]. For instance, acidity was determined for MoV(Nb)Te(Sb)–O-based M1 and M2 phases [129] with pyridine as a probe molecule, as shown in Fig. 13.

Comparison of the Brønsted and Lewis relative acidity of the M1 phases of MoVTe(Sb)NbO, expressed as the area under the pyridine peaks at 1540 and 1450 cm−1 normalised by the surface unit in the spectra recorded after desorption at 100 °C [129].

Both Brønsted and Lewis acid sites were detected. Acidity that is too strong favours total oxidation, as expected, and thus a moderate acidity is favourable towards better selectivity to acrylic acid/acrylonitrile. For instance, in a study of K-free and K–MoVSbO bronzes of (SbO)2Mo20O56, thus the M1-type structure [3], the selectivity towards acrylic acid was observed to be higher than for the starting sample, while when P was added to the M1 phase [130] acrylic acid selectivity was also improved. A medium acid strength for Sb samples and an even lower strength for Te samples [129] and Nb insertion decreases both acidities [129] and the Nb insertion decreases both acidities [129], while WOx added to MoVTeNb–O increases propane to acrylic acid by improving propene formation [131a]. Acidic properties were also studied [131b] using NH3 TPD and acid–base titration with a standardized NH4OH solution (−log[NH3] = 6.7) for Mo1V0.3Sb0.35Nb0.08On mixed oxide, calcined under N2, composed mainly of Sb4Mo10O11 (isomorphous of the M2 phase) and (VxNbyMo1−x−y)5O14 (M1-type) phases. Low Lewis acidity and no Brønsted acidity were observed for such a sample.

6 Electronic properties

In the first step of a redox mechanism, surface oxygen anions (O2−) are extracted to be inserted into products while cations are reduced according to: Mn+ + (n−p) e– → M(n−p)+. For example: V5+2O5 + 2e– → V4+2O4 + □ (where □ represents an oxygen vacancy), or V2O5 → V2O4 + ½O2, as usually written for an oxide reduction. In the absence of oxygen in the feed, these vacancies are filled by O2− diffusing from the bulk, as this reaction occurs in ionic conductors, and the solid is reduced more and more. In general, O2 is added to the reactants to promote reoxidation as the diffusion of O2− ions is too slow. The catalytic surface permits reduction of O2 according to: O2 + 4e– + 2□surf → 2O2–surf

In this step, the electronic properties of the solid are important parameters, as 4e− are necessary per O2. Some typical reactions have already been listed above in Table 1. The majority of selective catalysts are semiconductors due to defects present naturally at their surface. These selective catalysts could be n-type (n: negative or e− donors in the valence band) or p-type (p: positive or e− hole acceptor in the conduction band). Insertion of dopants allows us to modulate semiconductivity. The n-type is favourable to O2 activation to 2O2−, while the p-type and/or if the cation is more electropositive, other oxygen species can be formed at the surface according to: ; ; ;

Main selective oxidation reactions in heterogeneous catalysis from Ref. [95]. Process: NI = not yet industrialised; I: industrialised; P: pilot; R: research.

| Reaction type | Reactants | Products | Nb of e− | Catalysts | Yield mol % | State |

| Oxidative coupling | CH4 | Ethane+ Ethene | 2 4 | Li2O/MgO | 25 | NI |

| Oxidative dehydrogenation | Ethane | Ethene | 2 | Pt, mixed MoVTeNb oxides | 60 | NI |

| Propane | Propene | 2 | VMgO | 40 | NI | |

| n-Butane | Butene, butadiene | 2 4 | metal molybdates | 38 | NI | |

| Ethylbenzene | Styrene | 2 | FeO-AlPO4 | 70 | P | |

| Methanol | Formaldehyde | 4 | FeMO4 | 81 | I | |

| Isobutyric acid | Methacrylic acid | 2 | FePO4 | 75 | NI | |

| Oxychloration | Ethane,Cl2 | Vinyl chloride | 4 | AgMnCoO | 15 | NI |

| Ethene, Cl2 | 2 | CuPdCl | 90 | I | ||

| Hydroxylation | Benzene | Phenol | 2 | Ti or Fe zeolite | – | I |

| Selective oxidation | Methane | CO + H2 | 2 | Pt or Ni | 90 | R |

| Formaldehyde | 4 | MoSnPO | 16 | R | ||

| Ethene | Ethyloxide | 2 | Ag/Al2O3 | 8 | I | |

| Acetaldehyde acetic acid | 2 4 | V2O5 + PdCl2 MoVNbO + Pd/Al2O3 | 50 | I | ||

| Ethane | Acetic acid | 6 | MoVNb–O | 10 | P | |

| Propene | Acrolein | 4 | BiFeCoMoO | 86 | I | |

| Propane | Acrylic acid | 6 | MoVNb(Te,Sb)O | 8 | NI | |

| n-Butane | maleic anhydride | 14 | (VO)2P2O7 | 70 | I | |

| i-Butane | Methacrylic acid | 8 | HPA, oxides | 11 | R | |

| i-Butene | Methacrolein | 6 | SnSbO | 65 | NI | |

| o-Xylene | Phthalic anhydride | 12 | V2O5/TiO2 | 82 | I | |

| Acrolein | Acrylic acid | 2 | VMoWO | 85 | I | |

| Methacrolein | Methacrylic acid | 2 | 95 | I | ||

| t-Butylic alcohol | Methacrolein | 4 | BiMoFeCoO | 88 | I | |

| Ammoxidation | Propene+ NH3 | Acrylonitrile | 6 | MoBiFeCoNiO | 80 | I |

| Propane+ NH3 | 8 | VSbO,MoVO | 30 | I |

Such electrophilic species are more stable for more electropositive cations such as Mg2+, Ca2+, La3+, Ce4+, etc., and give carbon oxides for an unsaturated hydrocarbon. O2– is selective in ethene epoxidation on Ag0. O− species are very reactive at low temperatures for aldehydes to acids or benzene to phenol on titanosilicate or alkane activation using N2O instead of O2. Electron transfer properties are an important aspect of the Mars and van Krevelen mechanism, which implies high mobility of lattice oxygen anions and electrons to ensure a fast reaction. It also appears that electrical conductivity under different atmospheres is an important aspect for semiconductors, according to:

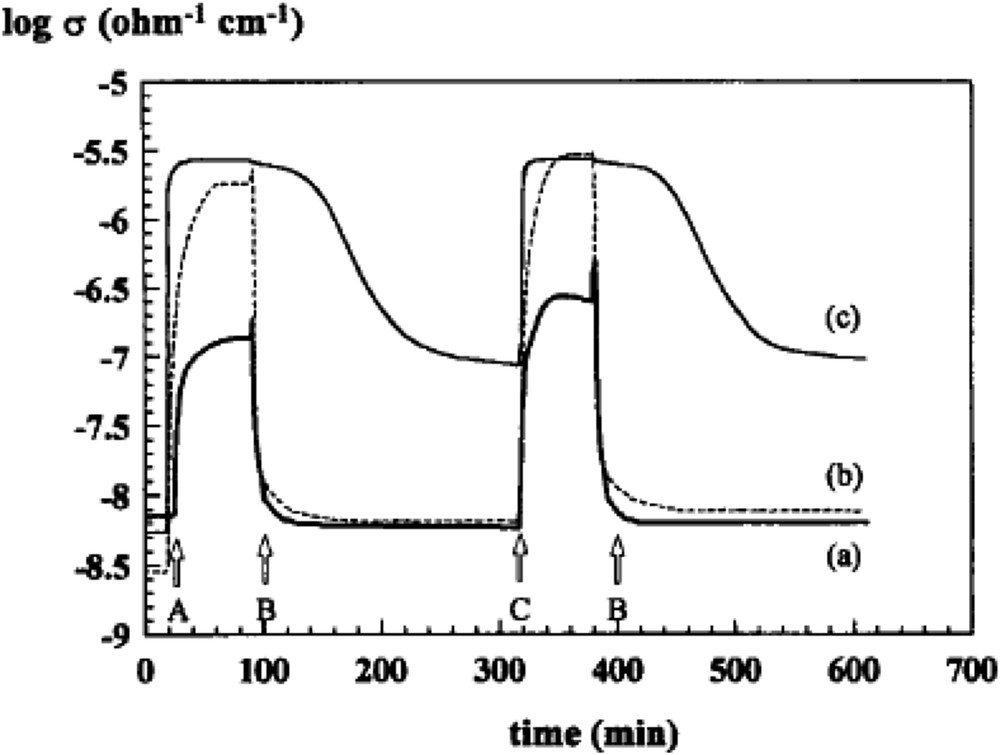

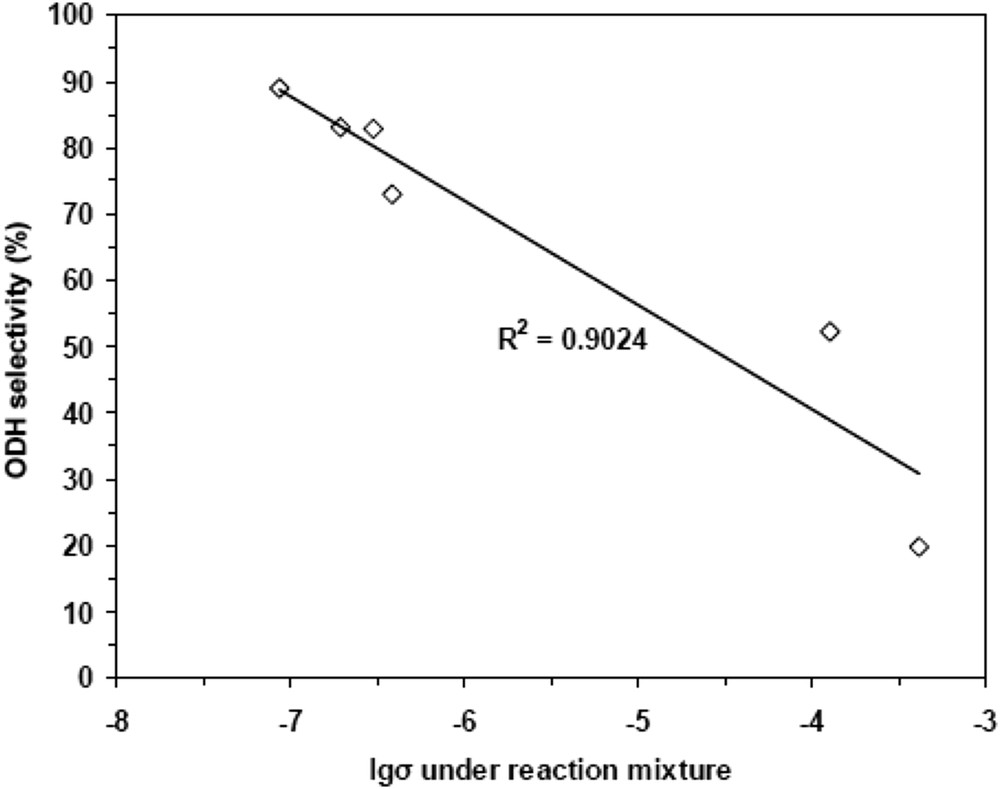

Under an oxygen atmosphere, the electrons trapped by adsorbed O2 are provided by the valence band of the oxide, and the electrical conductivity increases with consumption of oxygen. Conversely, exposure to a reducing gas creates oxygen vacancies, releases electrons in the valence band and creates new positive holes with a decrease of electrical conductivity. N-type semiconductivity (electrons available in the valence band) is favourable to activate O2 into nucleophilic O2−, whereas for the p-type (or if the cation is more electropositive), electrophilic species , O−, and may be formed and may lead more to COx. The use of electrical conductivity measurements for characterising redox properties has been used in many cases [132,133], for instance for VMgO ODH catalysts [132] or Nb-doped NiO catalysts [133a,b] used in ethane ODH, as illustrated in Figs. 14 and 15. The presence of alkali (Cs, K, and Li) affects the structure of MoOx domains and influences their electronic and catalytic properties.

Variations of electrical conductivity during redox cycles [115]: a) at 500 °C for 14 V/VMgO, b) at 800 °C for 14 V/MgO and c) for 45 V/MgO. A: C3H8/O2 = 1.2/1; B: vacuum; and then O2; C: C3

Variation of ethene selectivity at ethane isoconversion at 350 °C vs. electrical conductivity of NiO and Nb-doped NiO catalysts [133a].

An important aspect to consider is the number of electrons necessary for a given reaction such as CH3–CH2–CH3 + O2− → CH3–CHCH2 + H2O + 2e−. In Table 1, some important selective oxidation reactions and their state with respect to actual developments and number of electrons concerned in the reaction are shown.

7 Synergy or cooperation effect in mixtures of phases [134]

Mixed-metal oxides play a very important role in many areas of chemistry, physics, and materials science [135–146]. The combination of two metals in an oxide matrix can produce materials with novel structural or electronic properties that can lead to a superior performance in technological applications [135–156]. In general, there is a need to obtain a fundamental understanding of the phenomena associated with the behaviour of these complex systems. For many years, there has been a strong interest in studying the behaviour of mixed-metal oxide catalysts [135–156].

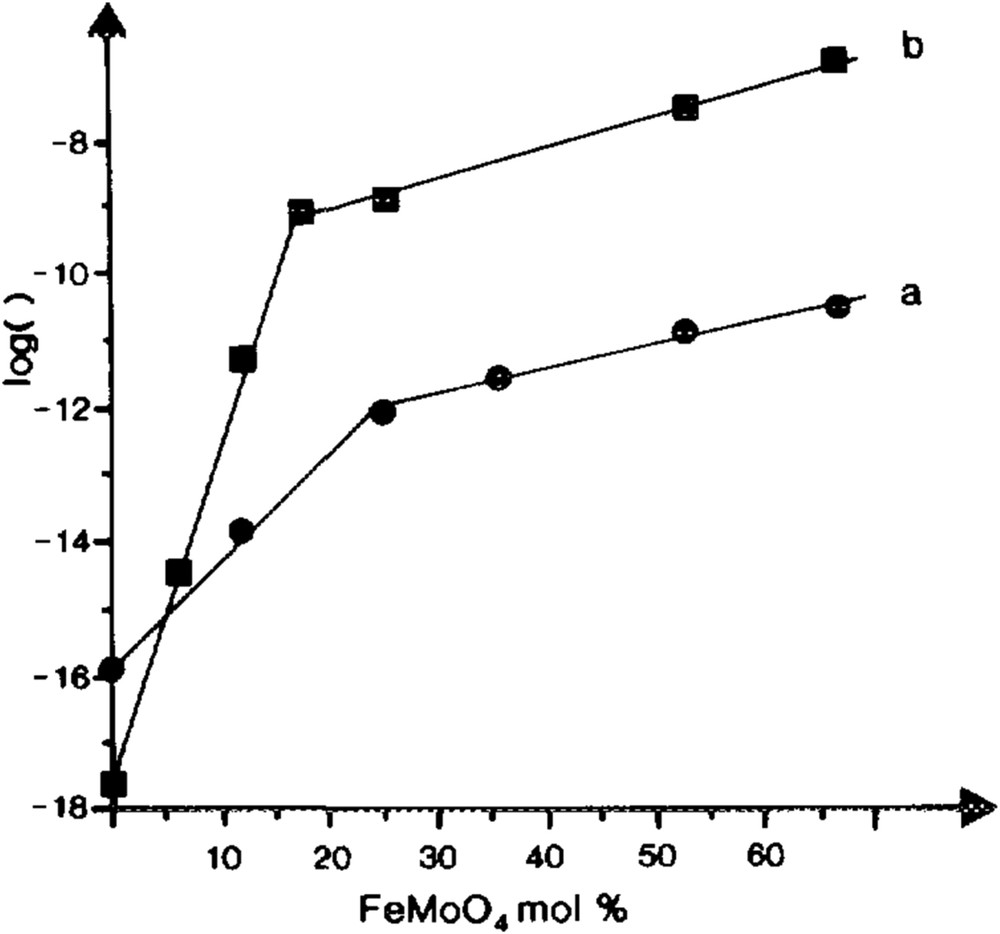

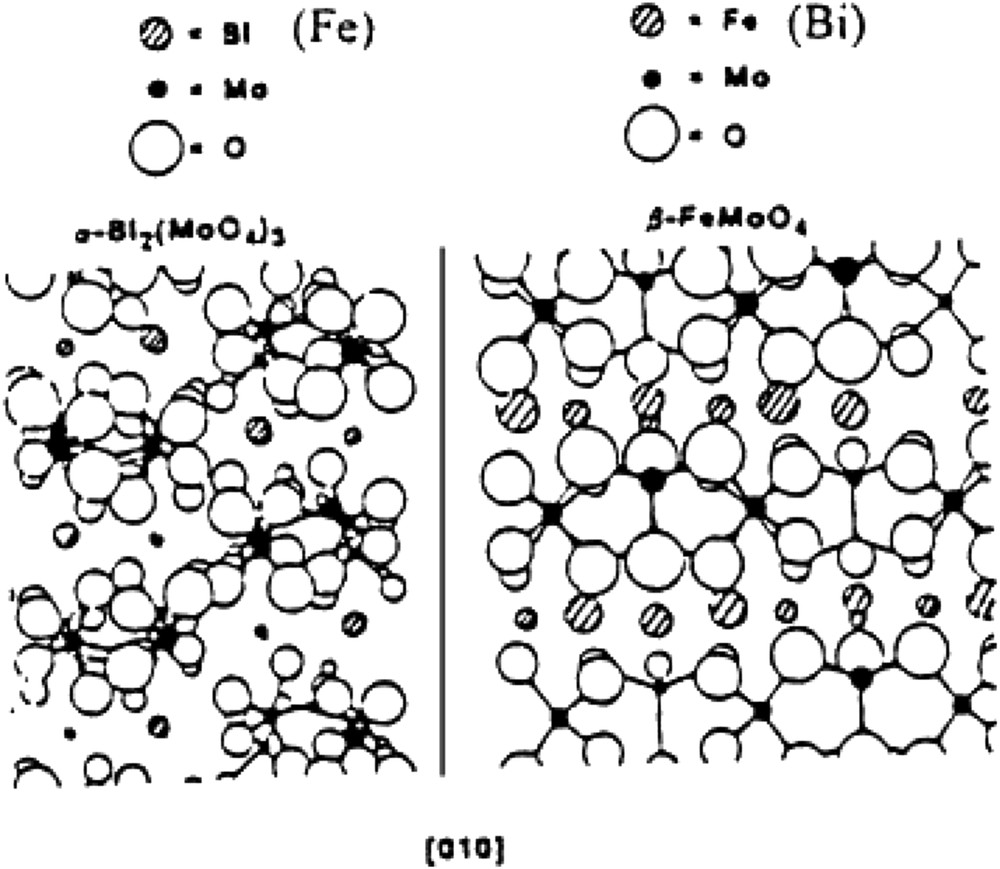

One of the most striking examples came from the bismuth molybdate-type catalysts developed at SOHIO in the 1960s for propene oxidation/ammoxidation in acrolein/acrylonitrile. The different phases (α, β and γ phases) are active for propene oxidation to acrolein, the α-phase being the best [157]. However, industrial catalysts, designated as multicomponent catalysts, also contain other molybdates, in particular Co(Fe)MoO4. Using electrical conductivity measurements and Mössbauer spectroscopy, intimate contact between the active Bi molybdate phase and its support Co(Fe)MoO4, as illustrated in Fig. 12, was shown to allow an improved redox mechanism by an easy electron transfer (Fe2+ ↔ e− + Fe3+). Synergy effects have very often been encountered in heterogeneous catalysis.

The synergy effects occur when the following conditions are met: (i) bi- or multi-phasic systems, and (ii) catalytic properties are drastically enhanced compared to each single component. This holds true for the VPO catalyst as described by Bordes, and also for the so-called multicomponent catalysts such as bismuth molybdates supported on Co(Fe) molybdates. In such a case, XPS and electrical conductivity measurements have shown that the synergy effect was in fact due to the enhanced electrical conductivity of the Co(Fe) molybdate support due to the presence of both FeII and FeIII in a CoII molybdate that facilitates the redox Mars and van Krevelen mechanism [158] (Fig. 16). Such an enhanced electrical effect was suggested to be related to a close contact between bismuth molybdate and iron molybdate phases, as schematised in Fig. 17.

a) log rate of acrolein formation in propene oxidation on Bi2Mo3O12:FexCo1−xMoO4 (0.043:1) at 380 °C; b) log σ of FexCo1−xMoO4 solid solution vs. its iron molybdates content [158].

Epitaxial match of the (010) face of Bi2Mo3O12 and β-FeMoO4 [159a].

Such synergy effect holds true for V2O5/TiO2-anatase or TiO2-B for o-xylene to phthalic anhydride [159b,c] or ammoxidation of toluene [159d]. It was observed for many mixed metal oxides (Ti, V, Mo, Nb, Te, Fe, Co, Bi, Sb, and P), whose structures allow local elastic constrains by distortion and connection of MOn coordinated polyhedra, for instance for M1 and M2 phases in MoVTeNb–O [31,159e]. The effect was interpreted as related to phase cooperation between different phases due to a close crystallographic adaptation of lattices at their mutual interface as schematized in Fig. 14 and designated as coherent interfaces [159f].

Recently, mixed Bi, Ce molybdates were found to be quite active for propene ammoxidation [159g], even more than the classical α-Bi2Mo3O12 phase. The catalyst, BixCe2−xMo3O12, e.g., BiCe1.5Mo3O12, of solid solution nature, has a scheelite structure, i.e. ABO4, where A2+ is a large cation 8-coordinated to oxygen and B6+ is a small cation tetrahedrally coordinated to oxygen. Substitution of a divalent cation by a trivalent one such as Bi results in a defect scheelite. The active site has been described as the Bi cation surrounded by two Ce cations, which readily undergo the Ce3+ ↔ Ce4+ redox phenomenon, and next to the vacant cation site, thus able to accommodate a lone pair of electrons.

Delmon et al. [160] have proposed to explain such a synergy effect, which they designated as the “remote control effect”, and which corresponds to “a multiplying phenomenon, i.e., a spillover species creates and/or regenerates catalytic sites which work many times”. In such a mechanism, one phase, the donor, dissociates oxygen to form a surface mobile species that spills over to the other phase, or the acceptor. The acceptor is the potentially active phase. The multicomponent catalyst system presents the “donor” and “acceptor” as it was shown for metal oxides [161] or sulphides [162] able to provide oxygen/sulphide ion spillover from one oxide/sulphide to the other (Fig. 18).

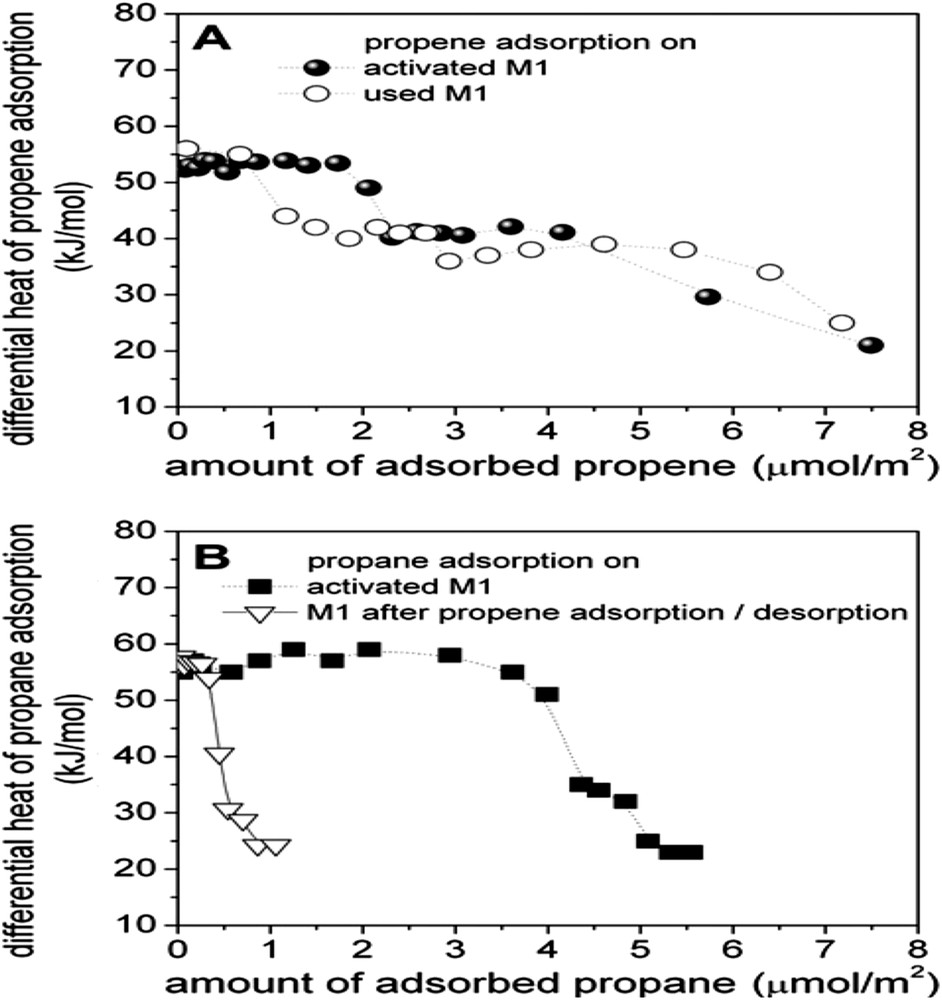

(A) Adsorption of propene on M1 MoVTeNb oxide before (filled circles) and after propane oxidation (open circles; reaction conditions for propane oxidation: 673 K, C3/O2/H2O/N2 = 3/6/40/51). (B) Adsorption of propane on activated (fresh) M1 MoVTeNb oxide (filled squares) and after adsorption and subsequent desorption of propene at 313 K (open triangles). The differential heat of adsorption is plotted as a function of coverage normalised to the specific surface area [161].

8 Changes in the catalyst surface structure during a catalytic reaction

This aspect is generally well known for such oxidation reactions in heterogeneous catalysis. For instance, it is well known that VPO catalysts necessitate many hours on stream before the best performances are reached. This phenomenon corresponds to a steady state of the catalyst surface under redox conditions, often with some elemental migration toward or away from the surface, as shown by XPS or LEIS analyses. In a study using microcalorimetry, Schlögl et al. [163] have shown that on an activated catalyst (calcined), the adsorption energy of propene and propane are approximately constant vs. coverage (57 kJ mol−1) but after the reaction, the energy decreases and is heterogeneous.

The first part is thus characteristic of a “single site heterogeneous catalyst” (SSHC) as defined by Thomas [164] but under reaction conditions, the surface is modified, and the sites are heterogeneous in strength (not satisfying the SSHC principle). Moreover, in-situ XPS analysis has shown that depletion of Mo and V enrichment did occur. This depletion may characterise element segregation or the formation of a sublayer of a composition different from the bulk, as shown by Millet et al. [165]. The surface composition of the M1 phase was shown [163] to differ significantly from the bulk, implying that the catalytically active sites are not part of the M1 crystal structure and occur on all terminating planes.

Acrylic acid formation correlates with surface depletion in Mo6+ and enrichment in V5+ sites. In the presence of steam in the feed, the active ensemble for acrylic acid formation appears to consist of V5+ oxo-species in close proximity to Te4+ sites in a Te/V ratio of 1.4. The active sites are formed under propane oxidation conditions and are embedded in a thin layer enriched in V, Te, and Nb on the surface of the structurally stable self-supporting M1 phase.

9 Dehydrogenation, oxidative dehydrogenation and selective oxidation of paraffins

Dehydrogenation of light alkanes, such as ethane, propane and isobutane, an endothermic and thermodynamically limited reaction, to their corresponding olefins is commercially well established. There are various processes such as Catofin (Lummus), Olefex (UOP), Linde-BASF, Snamprogetti-Yarsintez, and Star (Philipps petroleum) with chromia-alumina and fixed bed, supported Pt in a moving bed, chromia-alumina and fixed bed, chromia-alumina and fluid bed and supported Pt and moving bed, respectively. However, endothermicity and high coke formation, which necessitate frequent regeneration, thermal cracking and thermodynamic olefin yield limitation make the process not completely attractive and open the way to oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH) processes. A large number of catalysts, mostly V-based, have been investigated for propane ODH but have achieved propene yield only in the 8 to 20% range. The upper yield is attained with VMgO, Mg2V2O7 or MgVxSbyOz, while V2O5 supported on Al2O3, Bi2O3, La2O3, Nb2O5, SiO2, Sm2O3 or TiO2 gives inferior performance. Co and Ni molybdates have also been investigated with different dopants such as Fe, Mg, Ni or P and yielded near 15% with high productivity and no production of undesirable products.

At present, however, no catalysts have been found to be active and selective enough for the conversion of light alkanes to olefins to permit an industrial process to be acceptable. The MoVNb–O catalyst family from Union Carbide appears to have the most promising possibility at present for converting ethane to ethene and acetic acid, the problem being that both products are formed and limiting the acetic acid formation, if desired, is difficult. However, when adding Pd the selectivity to acid acetic may reach 80% [166a], whereas adding water in the feed increases acetic acid formation [166b]. The main processes for the synthesis of acetic acid include methanol carbonylation on Rh or Ir-based catalysts (originally by Monsanto, now also by Celanes, BP-Cativa, etc), liquid phase oxidation of acetaldehyde, n-butane and naphta and more recently on ethene oxidation in the gas phase (Showa Denko) and butenes liquid phase oxidation (Wacker) and the gas phase ethane oxidation. The later reaction C2H6 + (3/2)O2 → CH3COOH + H2O is only viable if a position for ethane is easily available and cheap. Different classes of catalysts have been proposed but the most performant ones are mixed (VNbMo)5O14 based oxides with a d-spacing close to 0.40 nm. The best composition was claimed to be Mo0.73V0.18Nb0.09Ox with 10% ethane conversion at 286 °C and almost total selectivity to ethene (vide infra §10).

10 Catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

The types of catalysts used in the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane are different from the catalysts used in oxidative dehydrogenation of higher alkanes. A very important number of catalysts with high catalytic activity for oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane have been observed to be inactive for propane, butane, etc. In contrast to the higher alkanes, ethane contains only the primary C–H bonds (420 kJ mol−1), whereas ethene, the ODH product, contains only the vinylic C–H bonds (445 kJ mol−1). The latter are strong and therefore the activation of ethane requires higher temperatures. Because the energy of the vinylic C–H bond is higher than the energy of the primary C–H bond, selectivity for ethane is expected to increase with temperature. Indeed, as shown in the literature [166–168], selectivity for ethene is higher at higher temperatures, and it is peculiar that catalysts that do not contain easily reducible metal ions are more selective in ODHE. However, a low yield and selectivity to olefins still prevent the industrial applications of ODH. Most catalytic systems reported in the literature give an ethene yield below 20%, and the industry requires the ethene productivity above 1 g (C2) gcat−1 h−1 at a temperature as low as possible [2]. Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane has been described in several papers and reviews [169–180]. Conversion of ethane and the selectivity towards ethene are governed by the catalysts and experimental parameters such as temperature, pressure, oxidant, amount of the active phase, and localisation of the active site.

NiO presents high catalytic activity for ethane conversion and ethene selectivity and the method of preparation of the catalysts has been observed to govern the catalytic activity [181,182]. NiO prepared by the sol-gel method [181] starts converting ethane at ∼275 °C, and the conversion increases up to 350 °C [181]. The ethene yield on NiO at 350 °C is 23% with ethene selectivity at 47%; at temperatures above 350 °C, the selectivity for ethene is completely lost. In this case the NiO catalysts deactivate at lower temperatures. The highest ethene yield for the NiO prepared by a sol–gel method was ∼15%, while with the NiO prepared by the precipitation method, the yield decreases to ∼8% and to 3% with the NiO prepared by a microemulsion method. The NiO sample prepared by using the sol-gel, with the high ethene yield, presents a smaller area compared with the other samples. The NiO prepared using sol-gel [183] gives a substantially higher ethane conversion and ethene yield than the NiO prepared by the oxalate [184] or microemulsion [182,184] method. The NiO prepared by Lemonidou has 80% CO2 selectivity [185]. This result shows that both conversion and selectivity in the catalytic oxidation of ethane on the NiO catalyst depend on the way in which the catalyst was prepared. The difference is both qualitative and quantitative: in one preparation, NiO is a fair catalyst for ethene production, while in another preparation, NiO causes the combustion of ethane. Interesting results have been reported for the NiO dispersed on several types of support and with NiO doped with other elements [186–191]. On the alumina support, Ni interacts strongly with the support by forming surface nickel aluminate-like species in the submonolayer, while NiO crystallites are formed on the top of the nickel/alumina interface for multilayer coverage [187]. The interaction with the support improves the catalytic performance, considering that unsupported NiO does not show high selectivity to ethene. However, adding one second oxide, which can be located between alumina and nickel, will diminish the interaction between the nickel and alumina support. When Nb was deposited on the NiO, the catalytic activity for ethane conversion was improved, and the ethene selectivity was higher. The high activity and selectivity added by Nb has been attributed to the electron transfer promotion played by Nb, leading to the facility for the activation of the C-H bond of ethane. It is possible that the Ni favours the higher dispersion of Nb.

Improvement in the catalytic activity has been observed when a very small amount of Nb was added [184] to the unsupported NiO prepared by the precipitation method – Nb0.03Ni0.97O. When the Nb was added to the NiO prepared by the citric acid method, no difference was observed. The conversion of ethane and the ethene selectivity increase when the amount of Nb increases for the NiO prepared by the precipitation technique [184,186] and diminish for the NbNiO catalyst prepared by the citric acid method, suggesting that the preparation method is very important. The Nb0.15Ni0.85O catalyst prepared by microemulsion [186] is stable on stream for 20 h at 350 °C, while the conversion of NbNiO prepared by the citric acid method drops slowly and steadily for 70 h, while selectivity increases. For the NbNiO prepared by precipitation [184], at a temperature of 380 °C, the conversion of ethane on Nb0.15Ni0.85O drops from 58% to ∼35% after 325 h on stream, while the selectivity increases from 67% to ∼78%. The degradation of the catalyst is not due to coking because heating the degraded catalyst to 450 °C in air for 30 min and then using it again as a catalyst at 380 °C did not restore its performance, but the deactivation can be due to the formation of NiNb2O6 [185]. ZrNiO has been prepared by the sol-gel method [181] and tested in the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane at temperatures between 250 and 450 °C. The conversion increases with temperature (up to 400 °C). At any given conversion, the ethene selectivities of 5ZrNiO, 10ZrNiO, and 20ZrNiO are close to each other and substantially higher than the ethene selectivity of NiO. For example, at 50% ethane conversion, the ethene selectivity of NiO is ∼47%, while the ethene selectivity of 10ZrNiO is ∼66%. Clearly, doping improves the selectivity and therefore the overall performance for ethane ODH. The best performance was obtained for 10ZrNiO at 430 °C with an ethene yield of 40% and an ethene selectivity of 66%. Doping with Zr improves the selectivity to ethene substantially, making the oxide less reducible, and binds the surface oxygen more strongly to the oxide. Because the only stable oxide of zirconium is ZrO2, Zr is a high-valence dopant (in NiO) and will act as a strong Lewis base, affecting the system in several ways. The NbNi, MgNi, LiNi, GaNi, NiO, AlNi, TiNi, and TaNi (Me0.15Ni0.85O, where Me is the dopant) catalysts [192] have been investigated in the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane in the temperature range from 300 to 425 °C. Ethane conversion, per gram of catalyst, decreased in the order: NbNi ≫ MgNi > LiNi > GaNi = NiO ≥ AlNi ≥ TiNi ≫ TaNi. NiO doped with Nb is the most efficient catalyst for breaking the C−H bond in ethane. Ethane conversion has been evaluated per unit area [192]. The BET measurements of the specific area give (in units of m2/g) 16.7 for NiO, 85.1 for NbNi, 7.6 for LiNi, 19.2 for MgNi, 67.8 for AlNi, 45.3 for GaNi, 18.6 for TiNi, and 78.9 for TaNi. Except the specific area of Li-doped NiO, all doped oxides have a larger specific area than NiO. If we normalise the conversion to surface area per gram, the order of the efficiency of the catalysts for ethane activation (conversion per area) changes to LiNi (0.139) ≫ MgNi (0.055) ≈ NiO (0.049) > NbNi (0.028) > GaNi (0.018) = TiNi (0.017) ≫ AlNi (0.011) ≫ TaNi (0.0004) [193]. In this case, Li-doped NiO is the catalyst most able to break the C−H bond. These results have been explained by calculating the energy of the oxygen vacancy formation in the surface layer [192]. 3.28 eV was obtained for NiO (011). The energy to make an oxygen vacancy in the surface layer of a doped oxide, near the dopant, is 2.65 eV for Li, 2.74 eV for Mg, 4.6 eV for Al, 4.25 eV for Ti, and 4.13 for Nb [193]. In general, a low-valence dopant will decrease the energy of vacancy formation, and this is what we see for Li-doped NiO. Mg has the same valence as Ni, and its ionic radius is comparable to the ionic radius of Ni, and we expect it to have a small effect on ΔEv, which is the case. Al, Ti, and Nb are high-valence dopants, and they increase the energy of vacancy formation. The values of these energies of oxygen vacancy formation suggest that doping with Li and Mg will activate the oxide, and it will convert more ethane than NiO [192,193]. The calculations suggest [192,193] that the high-valence dopants Al, Ti, and Nb will make the doped surface less active than NiO, for the Mars−van Krevelen mechanism. However, it is probable that O2 adsorbs on the dopant and ethane reacts with it.

The catalysts that contain oxides of the alkali or alkaline earth metals (of the IA and IIA groups) present activity in the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane at high temperatures (870 K) [194]. With these catalytic systems, the catalytic activity/ethene selectivity can be improved by adding the chlorine-containing compounds to the feed mixture to generate ethyl radical entities or when a catalyst is doped with halides [194–197]. Some improvement in the selectivity to ethene is also observed for the system doped with Na, B, lanthanide oxides and SnO2 [198–200]. Several other catalytic systems, such as LiCl/NiO [201,202] LiTiO, and LiMnTiO [203], have been proposed. For some, an improvement of the selectivity to ethene has been observed, but they do not show improvement in the ethene yield in comparison with the base system Li2CO3/MgO(Cl). An interesting system based on LaF3 associated with a rare earth oxide (CeO2 and SmO2) and doped with BaF2 has been reported as a catalyst that allows attaining approximately a 35% yield of ethene from ethane [204,205].

A large number of catalysts have been investigated for the ODH of ethane for example, using Mo–V-based catalysts [206–209]. In the case of molybdenum catalysts, the molybdena phase is involved in the ODH of ethane and the secondary over oxidation of ethene to COx [210]. In general, we have observed [210] that on the alumina-supported catalysts, alumina contributes to the primary deep oxidation and dehydrogenation routes of ethane to COx and carbon deposit, which proceed effectively over the acidic centres. When the molybdenum amount is higher, the monolayer coverage leads to a decrease in the catalytic activity due to the growth of the Al2Mo2O4 crystallites. Selectivity to ethene increases when loading increases up to 15 wt.% and then remains constant. The best catalytic performance can be achieved with highly dispersed two-dimensional molybdenum species, which fully encapsulate the alumina surface [211].

The Mo/V/Nb catalysts can be efficient catalysts for ethane ODH [119,212–217]. The Mo/V/Nb/O catalyst is selective to ethene but is only moderately active at temperatures lower than 300 °C [212,218,219]. When Sb is added to MoV, the selectivity to the olefin is 64% at an ethane conversion of 16.8% at 380 °C with a Mo6V2Sb1Ox catalyst [220,221]. The selectivity to ethene higher than 80% at an ethane conversion of 65% was reported for samples prepared by heat treatment in N2 at 600 °C [222]. The catalytic performance of this catalyst has been attributed to the presence of the (SbO)2M20O56 (M = Mo, V) crystalline phase.

Mo/V/Te/Nb/O catalysts, prepared by hydrothermal synthesis [223], were found to be extremely active and highly selective in the ODH of ethane, especially those with a Mo-V-Te-Nb atomic ratio of 1–0.15–0.16–0.17 and heat-treated at 600–650 °C. On the best catalyst, selectivities higher than 80% at ethane conversion levels higher than 80% (75% ethene yield) were obtained at relatively low reaction temperatures (340–400 °C). The catalytic performance was related mainly to the presence of the orthorhombic Te2M20O57 (M = Mo, V, Nb) and (V, Nb)-substituted u-Mo5O14. Interesting results have been reported on RE oxides and oxychlorides, often in combination with alkali or alkaline earth metal oxides: Sr/La/Nd/O, Sr/La/Fe/Cl/O, Sr/La/Cu/Cl/O, Y/Ba/Cu/O [224–226], Li/Dy/Mg/O [227], Li/Dy/Mg/O, and Sm/Na/P/O [228]. With these catalysts, which operate at reaction temperatures higher than 700 °C, the mechanism is not the conventional redox mechanism. These systems yield ethene productivities higher than 1 kg kgcat−1 h−1, which is the limit value below which the productivity is too low to be interesting for commercial applications. Conversely, with the other catalytic systems, the ethene productivity achieved is lower than 1, with the sole exception of NiO/MgO [188]. Excellent performance has also been observed with Fe/P/O [229] and mesoporous V/Mg/O [230] catalysts. The catalytic activity for catalysts based on reducible oxides (Mo, V, W, Nb) is usually significantly higher, but selectivity to alkenes is lower in comparison with the selectivities of the systems described above.

Oxides of vanadium, molybdenum, and niobium have been shown to be active in oxidation at temperatures as low as 200 °C [231]. The conversion of ethane to ethene on various supported metal oxides such as vanadium, molybdenum, or boron oxides has been reviewed [232]. Important values of the selectivity to ethene have been observed on Keggin-type heteropolymolybdates containing Sb and W.

The inconvenience of these catalysts consists in their deactivation. Between the α- and β-phases of NiMoO4, we found [233] that the α-phase is more selective and active than the β-phase. For the mixed oxide systems of the MVSb type, (M, ¼ Ni, Co, Bi, and Sn), [234,235] the best results were found for the NiVSb catalyst. We have also found by an evolutionary approach that the CrCoSnW and CrMo mixed oxides supported on an α-Al2O3 are promising new catalysts for the ODHE.

A V-based catalyst has been reported [206,208,222,230,236–245] to be one of the most active and selective single metal catalysts of the ODH- based catalysts, and MoV mixed oxides are the most widely studied transition-metal catalysts for the ODH of ethane [119,217,246–252]. The catalytic activity of the MoV-based catalysts supported on TiO2 and Al2O3 was investigated in the ODH of ethane [119]. The catalytic properties of the acidic and basic forms of Ni-, Cu-, and Fe-loaded Y zeolites were investigated in the ODH of ethane to ethene [253]. An overview of the literature studies shows that the vanadium-based catalytic system as the mixed oxide catalysts containing vanadium and vanadium supported on mesoporous inorganic solids or micro- and mesoporous materials is one of the most active and selective single-metal catalysts in ODH [2,236,237].

As has been observed for several reactions, the structural, textural and acid/base properties play important roles in the activity of the mesoporous material in ODH. V-MCM-41 [254], V-alumina [238] and V-mesoporous alumina [246] have been reported to be active catalysts in the ODH of ethane. Low-V-loading catalysts are the most selective in the alkane oxydehydrogenation, but low productivities are generally obtained as a consequence of the low number of active sites. Therefore, one must use high surface area silica supports to obtain high conversions, keeping the selectivity at the desired level. V-MCM-41 and V-MCM-48 can be prepared by following a one-pot synthesis procedure [255–262]. These materials show redox properties, and they have recently been reported as selective catalysts in the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane. A key factor in the design of efficient catalysts for alkane oxidative dehydrogenation is the isolation of active sites [263]. Therefore, the isomorphous substitution of active metal species, e.g., vanadium, into microporous and mesoporous materials is an attractive strategy for designing new catalysts for this reaction [254,260,264–273]. The main drawback of these systems is that they do not always maintain the structure if high V contents are incorporated. Furthermore, the incorporated V species may sometimes be easily withdrawn from the structure during the reaction. In many cases, site isolation has been achieved by simply depositing the active phase by impregnation over these high surface area supports. Examples include V-containing high-surface siliceous materials such as MCM-41or SBA-15 [254,262,274–283]. In these systems, the catalytic activity of vanadium in the ordered mesoporous materials is strongly influenced by its local environment and the co-existence of acid sites in the host material.

Acidic materials are preferred for the ODH of ethane [269–271]. In the case of VCoAPO-18, the presence of both acid sites (related to the presence of Co2+ cations) and redox sites (related to the presence of V5+/4+ and Co3+/2+) seems to be an important factor in achieving high selectivities to ethene during the ODH of ethane [284]. An outstanding value of ethene productivity, close to10 kg olefin per kg of catalyst per hour, has been reported for a VOx-MCM-48 catalyst containing 2.8 wt.% vanadium oxide [285]. The selectivity to ethene is favoured on acid supports [286,287]. However, a better metal dispersion can be achieved by using a high surface area alumina, as has recently been reported by our group [288]. A mesoporous alumina was used as a support for vanadium oxide in the ODH of ethane, obtaining a high productivity to ethane as a consequence of a remarkable dispersion of vanadium on the surface of the support. Al2O3-supported vanadia catalysts have been shown as one of the most active catalytic systems in the ODH of lower alkanes, especially ethane [207,289–291], while molybdenum supported on alumina materials has been reported to be relatively active for the ODH reactions [292–294]. It has been reported that the use of mesoporous alumina instead of conventional alumina for the Mo, V and Mo-V catalysts led to an increase of both the catalytic activity and the selectivity to ethene explained by the better metal dispersion using a high surface area alumina [246,288]. The selectivity in the ethene formation has been reported for the Mo-V-mixtures in comparison with pure V- or Mo-mesoporous alumina catalysts [246]. The improved selectivity to ethene obtained for the MoV catalysts would be mainly due to two factors: (i) presence of highly selective vanadium species, isolated as VO4 units, and (ii) the coverage of non-selective sites of the support by molybdenum oxide species.

The catalytic results show that V-containing catalysts are ca. four times more active than pure Mo catalysts, whereas Mo-V-containing catalysts were found to be the most selective catalysts in the ODH of ethane to ethene, indicating that a synergetic effect between Mo and V takes place [246]. In the conversion of ethane to ethene, a large number of catalysts such as catalysts based on alkali and alkaline earth ions and oxides, as well as catalysts based on reducible transition metal oxides and other catalysts such as B/P oxides, Ga/zeolite, LaF3/SmO, and Sn/P have been tested.

It is interesting to note that the catalysts that show good selectivities at higher temperatures generally do not contain easily reducible metal ions such as V, Mo, or Sb. Many of the catalysts for the lower-temperature operation, on the other hand, contain these reducible cations. In a study using a Li–Mg oxide, it was established that gas-phase ethyl radicals could be generated by the reaction of ethane with the surface at approximately 600 °C [194]. These radicals could be trapped by matrix isolation and identified by electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Among the factors that influence the catalytic properties, it appears that the method of preparation of the catalysts is an additional factor in the optimisation of the catalyst. In this review, we attempt to contribute to the understanding of the activity of vanadium containing HMS, MCM-41 and SBA-15 materials in the ODH of ethane. The main attention is given to the activity of vanadium-based catalysts in the ODH of ethane, the effect of reaction conditions (temperature, oxygen and ethane concentration, and contact time) on the activity/selectivity of V-HMS (a chosen catalytic system) in ODH of ethane and the relationship between the structure of the vanadium species and the activity/selectivity in the ODH of ethane.

These materials show redox properties, and they have recently been reported to be selective catalysts in the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane. The selectivity to oxydehydrogenation products on V-containing mesoporous materials is higher than the selectivity corresponding to silica-supported vanadia catalysts. However, these high selectivities when using mesoporous MCM as the support were usually obtained at a low V content, while a significant decrease of selectivity to propene from propane occurs on catalysts with a V content higher than 1 wt.% [260]. An alternative method to incorporate vanadium onto silica surfaces is the use of post-synthesis procedures.

11 Thermodynamics – Kinetics

The dehydrogenation of an alkane and particularly of the ethane (Eq. 1) is an endothermic reaction, and significant amounts of heat must be added to sustain the reaction, which requires high temperatures.

| CH3–CH3 → CH2CH2 + H2 | (1) |

| CH3–CH3 + ½O2 → CH2CH2 + H2O | (2) |

Instead of molecular oxygen as the oxidant, carbon dioxide can also be used as a nontraditional oxygen source or oxidant [295–301] according to Eq. 3:

| CH3–CH3 + CO2 → CH2CH2 + CO + H2O | (3) |

The knowledge of the mechanism of oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane is very important and is a great challenge which depends on several parameters, but the nature of the catalyst is dominant.

Several aspects should be known, such as: (1) the nature of the interaction of ethane with the catalysts, (2) the formation of the alkyl species by the dissociation of the C–H bond, (3) the transformation into alkene by the interaction between the adjacent oxygen surface and the alkyl species followed by the (4) reduction/oxidation of the catalyst. The degree of the C-H dissociation depends on the temperature and pressure and the dissociative adsorbed entities can react to give ethane, but the reaction is rather slow [309–312], compared with hydrogenation of the weakly adsorbed ethene. The stability of activated complexes in C–H bond dissociation steps depends on the ability of the active oxide domains to transfer electrons from lattice oxygen atoms to metal centres [313].

At very high temperatures [3], the ethane molecule reacts on a catalyst to produce an alkyl radical, which desorbs from the surface to undergo homogeneous gas-phase reactions. At lower temperatures, the alkyl species remains adsorbed on the surface. Elimination of the alkyl species produces an alkene. The alkene molecule may readsorb to react further in the sequential reaction. Because alkenes (and other unsaturated hydrocarbons with the same number of carbon atoms) are the intermediate products in the sequence, their further reaction to form any oxygen-containing product such as organic acids, anhydrides, aldehydes, and carbon oxides would lower the selectivity for the dehydrogenation. Thus the selectivity for the alkene is higher at lower alkane conversions but decreases with increasing conversion. Another competing pathway for the adsorbed alkyl species is the formation of a surface alkoxide, which could be further oxidised to aldehyde and carboxylates, and perhaps eventually to carbon oxides.

Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane is described by several kinetic models as a power law model, a “rake” model, an Eley–Rideal model, a Langmuir–Hinshelwood model, and a Mars Van Krevelen model-the redox model [314–319].

11.1 Power Law model

The power law model is usually used as the first approximation in kinetic studies of catalytic reactions. This model [320,321] correlates the rate of the reaction with the partial pressures of the reactants. The kinetic equation of the power law is presented in Table 2.

Kinetic equation.

| Mechanism | Kinetic equation |

| Power Law model | |

| Eley–Rideal model (ER) | |

| Langmuir–Hinshelwood model (LH) | |

| Mars van Krevelen model (MvK) |

11.2 Eley–Rideal model

This model features a reaction between adsorbed O2 and a gaseous or weakly adsorbed reactant. According to the Eley–Riedal (ER) model [314,315], equilibrated adsorption of species A on the catalyst surface is assumed followed by, its subsequent reaction with molecule B provided by the gas phase. Langmuir assumptions for the adsorption of A were applied, a partial order of B as one was taken, and a rapid desorption or low coverage by products was assumed. The reaction rate is then expressed by equation presented in Table 2.

11.3 Langmuir–Hinshelwood model LH (uniform surface with one type of site)

The Langmuir–Hinshelwood mathematical treatment [316,322] is more difficult and starts from the assumption that all stages but one, the rate-determining step (e.g., the surface reaction), are very close to thermodynamic equilibrium. The concentrations of the components occurring in these equilibrium stages are interrelated by the conditions for the chemical equilibrium. Different rate-determining steps are possible.

11.4 Mars van Krevelen model (MvK) – the redox model – lattice oxygen

The redox model was developed by Mars and van Krevelen (MvK) for naphthalene oxidation [103,323]. According to this model, oxygen for the reaction comes from the lattice of the catalyst and the reduced catalyst is then re-oxidised by gaseous oxygen. In the stationary state, the oxidation rate of the catalyst is equal to its reduction rate. The stationary state is determined by the ratio of the rate constants of both reactions. A steady-state adsorption model (SSAM), which can be regarded as a surface variant of the MvK model, was developed by Downie et al. [324,325] and applied also to describe the kinetics of the vapor-phase oxidation of o-xylene over the vanadium oxide catalyst [326,327]. In this model, a steady state is assumed between the rate of adsorption of oxygen on the surface and the rate of removal of oxygen by the reaction with hydrocarbon from the gas phase. Some additional assumptions can be made in this model, such as: 1) oxygen dissociates, or 2) oxygen desorption is not negligible.

The ER, LH, and rake models describe the catalytic reaction, while the redox model concerns variations in the state of the catalyst. The ER and LH models are concurrent models. While they are not concurrent with respect to the redox models (e.g., ER and SSAM), it is possible that the reaction proceeds according to the ER-SSAM model.

Interesting observations concerning the MvK mechanism have been reported on the Zr–NiO catalysts [181]. It has been observed that with the insertion of Zr into NiO, ethene selectivities of 5ZrNiO, 10ZrNiO (66%), and 20ZrNiO are superior compared with NiO (47%). Doping with Zr improves the selectivity to ethene substantially, making the oxide less reducible, and binds the surface oxygen more strongly to the oxide. Because the only stable oxide of zirconium is ZrO2, Zr is a high-valence dopant (in NiO) and will act as a strong Lewis base, affecting the system in several ways. NiO is a better oxidant, as explained by the presence of their vacancies, while the Zr is a strong Lewis base. In this case, it is most probable that the electron transfer from Zr to the electron–holes of NiO with Ni vacancies is performed; O2− is formed by this transfer of an electron from Zr to O− sites of the Ni vacancy. Zr will increase the binding energy of the oxygen atoms found nearby the oxide surface, equivalent to making these oxygen atoms less reactive. Therefore, if the rate-limiting step in ethane ODH is the dissociative adsorption of ethane to make a hydroxyl and an ethoxide with the oxygen atoms on the surface (MvK mechanism), the presence of Zr should make this reaction more difficult. As we have already explained, a high-valence dopant adsorbs O2 from the gas phase. If the binding energy of the O2 to the Zr is not very large, the adsorbed O2 is reactive and can break the C−H bond in an alkane. Zr acts as a typical high-valence dopant (without O2 adsorbed on it).

An interesting kinetic model was developed [328] to understand the ODH of ethane on MoVMnW mixed oxide catalysts, when the following assumptions were made [250,253,329] : (1) the ODH is isothermal, (2) a catalyst deactivation is a function of time-on-stream (TOS), and (3) a single deactivation function is defined for all reactions, and a thermal conversion is neglected. Ethane reacts with oxygen to form ethene or carbon oxides. Ethene, then, undergoes a subsequent oxidation to COx and CH3COOH. Apparent activation energies of 60.5 ± 8.0, 139.6 ± 15.7, 92.4 ± 13.9, and 24.1 ± 2.2 kJ mol−1were obtained for the ethane ODH, ethane combustion, alkene combustion, and the formation of CH3COOH from C2H4, respectively. On the K–Y zeolite [253], apparent activation energy for the formation of ethene was ∼51.5 kJ mol−1 and on the VOx/SiO2 catalysts [330], the apparent activation energy for the formation of ethene was ∼63.2 kJ mol−1, which correlates with the MoVMnW catalyst. Studies of ODHE on a VOx/g-Al2O3 catalyst [331] showed that the main products were ethene, CO, and CO2. Taking into account the results of the ethane conversion to ethene and the relationship among CO and CO2, the parallel reaction takes place. CO was formed by the consecutive oxidation of ethene. Total oxidation of these hydrocarbons was observed to occur only in the presence of gaseous oxygen by the LH mechanism while the ethene formation occurred with the consumption of lattice oxygen, followed by the MK mechanism. The reactivity data for catalysts made of supported vanadium oxide are consistent both with kinetically relevant steps involving the dissociation of C–H bonds and with a MvK redox mechanism involving lattice oxygen in C–H bond activation. The resulting alkyl species desorbs as an olefin, and the remaining O–H group recombines with the neighbouring O–H groups to form water and reduced V centres. The latter are re-oxidised by irreversible dissociative chemisorption of O2. Surface oxygen, O–H groups and, especially, oxygen vacancies are the most abundant reactive intermediates during ODH on active VOx domains [332–334,337]. The contribution to COx formation, conversely, derives mainly from adsorbed O species, at least in ethane ODH [331]. The CO oxidation occurs primarily by a redox mechanism or in addition, by the participation of a gas phase or weakly adsorbed oxygen. Data analysis has been performed with the application of the differential method, and pre-exponential factors and activation energies for the reaction network have been calculated. The model was obtained on the 7.7 wt.% VOx/SiO2 [335] to obtain information on the contributions of particular reaction products and did not consider the competitive adsorption by different species. COx has been found to be formed mainly from ethene and acetaldehyde and to a lesser extent from ethane, but ethane is practically the only source of acetaldehyde [335].

The ER model [330] was combined with the SSAM for ODHE on a VOx/SiO2 pure catalyst and a catalyst doped with potassium. The influence of the potassium additive and the adsorption of water on the particular rate constants have been discussed. For this catalyst and for ODHE, there has been shown to be little influence of the adsorption of water and the potassium additive on the rate constants of the particular reaction steps. Both pure and doped catalysts worked in an almost fully oxidised state. On the 19.5 wt.% VOx/SiO2, [336] the MK model for the description of kinetic data was applied. The model described the experimental data quite well for low partial pressures of ethane and oxygen (10%), but for higher partial pressures, the typical deviations observed between experimental and calculated values were larger (25%). Introduction into the model sites that are supposed to be inactive for the ethene formation improved the description of the kinetic data at higher partial pressures. In both models, the reduction of oxidised sites was a limiting step in ODHE, so the VOx/SiO2 catalyst can be considered to work predominantly in an oxidised state. Considering the results of the catalytic properties of various materials used in ODHE [42,233,331,335], one can state that kinetics of ODHE for the above-mentioned systems generally can be explained by the parallel-consecutive reaction network, in which both the selective reaction (formation of alkene) and consequent oxidation to carbon oxides and the parallel direct formation of carbon oxides have taken place. The formation of an ethoxy complex is proposed as the first step of the ODH reaction of ethane for most of the mechanistic models, but successive stages of ODHE proposed by different authors are different and depend on the applied catalyst. In the literature, a parallel-consecutive reaction network has most often been used for the description of the experimental data for ODHE. Kinetic investigation evidenced that COx is formed mainly by consecutive oxidation of the alkene and to a lesser extent, on a parallel route by direct oxidation of the alkane. The author also remarked that the MvK mechanism is most frequently proposed for describing the kinetics of the ODH of the light alkanes. Other mechanisms are used rather seldom and mainly for the kinetic description of paths in the ODH of alkanes in which COx is formed.

12 General conclusions and perspectives

In this review, we have limited ourselves to heterogeneous selective oxidation reactions on metallic oxides, and we have given the main features and requirements for better activity and overall selectivity. The majority of the processes described are rather old, namely, more than half a century old, although many of them have been improved during the years either by changing the preparation and activation procedures or by chemical engineering in reactors and process improvements. For environmental reasons, some processes have to be suppressed due to the use of reactants that are not environmentally friendly or solvents such as sulphuric acid, cyanic acid, etc. If many challenges have been solved more or less perfectly, improvements are still possible. One of the most important challenges remaining is alkane upgrading to olefins or carboxylic acids/aldehydes, in particular methane. The most researched possibility is to discover single phase structures, containing the desired catalytic functionalities, without the need to use two structurally well matched separate phases operating in a phase cooperative mode. There is ample latitude left in optimizing the structure of known catalysts. Reactions such as simultaneous dehydration and selective oxidation or ammoxidation of biomass derived intermediates such as glycerin, lactic acid or 3-hydroxypropionic acid to acrylic acid or acrylonitrile, respectively, are important perspectives to follow up.

Clearly, partial oxidation solid catalysts are very complex as they necessitate multifunctionality and behave most often as “living” or “breathing” materials at their surface. Oxidation reactions are structure-sensitive, i.e., necessitate an ensemble of atoms as active sites isolated from the other to avoid overoxidation to CO2. The size of these ensembles depend on the organic reactant, its nature and size) and on the number of electrons necessary for the redox reaction to occur. Acid–base and overall redox properties are quite important to activate reactant molecules, although acidity, that is too strong could be deleterious and is often neutralised with low amounts of a base such as alkaline ions. The redox phenomenon that is crucial to permit the Mars and van Krevelen mechanism to function is an important property that could be enhanced by higher electrical conductivity of the surface or of a support or another phase for multicomponent catalysts. During activation of the catalysts, which often necessitates hours on stream to maximise catalytic performance, the solid surface composition and atom arrangements are often modified, as observed using surface techniques such as XPS and LEIS, leading to a surface structure at variance with the bulk structure although strongly depending on the bulk structure (epitaxial contact). This also holds true for modifications in the surface composition during the catalytic reaction.

In the present stage the most important trends concern oxidation of ethane to ethene or acetic acid and propane (amm)oxidation on MoVTe(Sb)Nb–O catalysts (Mo5O14 based catalysts with Te, Sb or Nb incorporated into the structure, leading to M1 and M2 phases). A desirable aim/challenge is to substitute Te, which is easily reducible and thus volatile and poisonous, by any other similarly selective element such as Bi or Sb. Note that Bi has already been tried but without success.

Another approach is based on the reactors used for the reaction chosen. Usually fixed beds are preferred as thermal control is easier but considering the size of the tubes, secondary reactions may occur if the first intermediate product (e.g., the olefin) is easily converted. Moreover, safety reasons may impose a low reactant over the oxygen ratio (within explosion limits). This is why fluidized or moving bed reactors have been developed, as it was the case by DuPont Co in Asturias, Spain, for butane to maleic anhydride on VPO catalysts [338,339]. Further developments of chemical engineering and reactors remain an attractive possibility for the future, to circumvent problems in selective oxidation reactions [340]. A possibility resides in using membrane reactors to maximize the feed rate of oxygen and organic compounds, mainly with the aim of increasing butane concentration (limited within explosion limits in fixed bed reactors), thus providing higher production rates [341,342]. For instance, a VPO catalyst was deposited as a thin layer on a mesoporous MFI membrane [343] or packed in a tube of porous alumina. Metal oxide nanoparticles entrapped in porous materials may well be interesting for selective oxidation reactions, such as alkane up grading ones, but until now and to the best of our knowledge no success was mentioned. A conventional fixed bed reactor could also be used with a porous metallic membrane immersed in a gas-solid fluid bed reactor [344].