1. Introduction

Tsuji–Trost allylation constitutes one of the most versatile palladium-promoted transformations used in general organic synthesis [1, 2, 3, 4]. The ability to build C–C, C–N, C–O and C–S bonds, in high yields, is the main feature of this allylation reaction. Although several metals catalyze this process, palladium is the most commonly employed in the racemic or non-racemic synthesis of natural products [5, 6, 7, 8, 9] and molecules of pharmaceutical interest [10, 11, 12]. The most important features of this reaction are: (a) having the widest scope allowing the reaction with assorted nucleophiles; (b) offering a high regioselectivity in the attack of the nucleophile to the allylic moiety. In addition, the search of mild and environmentally benign conditions with the recovery and recycling of the palladium catalytic systems are crucial aspects nowadays. Classical green and catalyst-recoverable Tsuji–Trost allylation methodologies have involved aqueous [13] micellar catalysis [14, 15], pure water/aqueous media [16], metal free organocatalyst [17] or insoluble palladium aggregates [18], which will be compared with the results obtained in this work (see below).

Focusing our attention on the efficiency and recovery of palladium catalysts using ionic liquids (IL), they have been widely tested in general palladium-catalyzed processes [19]. However, for the Tsuji–Trost allylation a short number of publications have been published. In all of them the IL was combined with the palladium salt in non-asymmetric processes [20, 21, 22, 23] or in asymmetric versions [24, 25, 26, 27]. Catalytic ionogels, based on the entrapment of an IL [28], chitosan supported ionic liquid phase (SILP) [29], and liquid–solid hybrid catalyst [30], were different combinations of IL and palladium(II) salts. In many cases TPPTS [(triphenyl phosphine-3,3′,3′′-trisulfonic acid trisodium salt)] was used as hydrosoluble ligand. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no examples of the so-called task-specific ionic liquid (TSIL), which are designed and prepared for special reactions have been considered for the study of the Tsuji–Trost allylation.

In this work, the synthesis and use of a (TSIL) BMIM-ionic liquid-phosphane⋅Pd complex, as recoverable catalyst, in the substitution of allylic acetates by assorted nucleophiles will be surveyed. A special effort will be invested in the analysis of the n-selectivity [31], and the reproducibility of the recovery method for the catalytic system.

2. Results and discussion

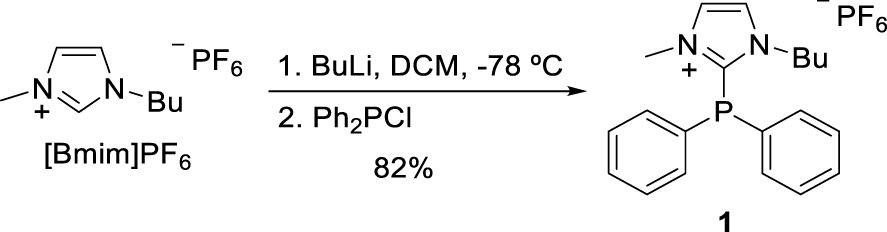

The TSIL ligand 1, prepared according to Scheme 1, was successfully employed as ligand in silver(I)-promoted 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions [32] and also in the palladium(II)-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura coupling in water [33].

Synthesis of the TSIL-P.

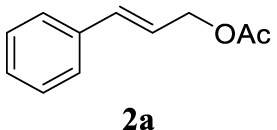

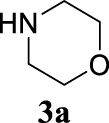

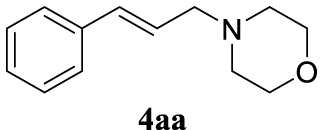

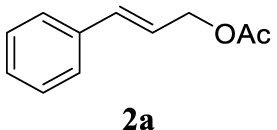

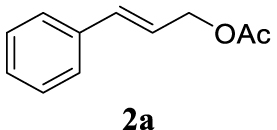

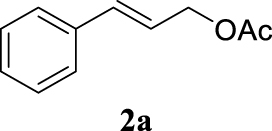

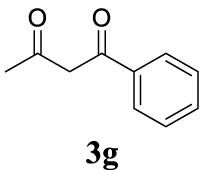

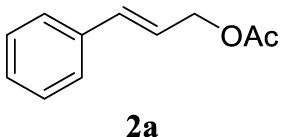

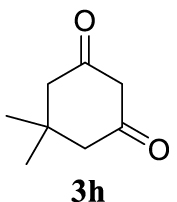

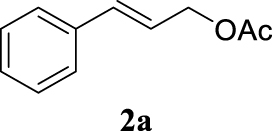

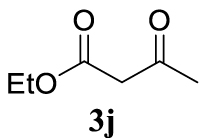

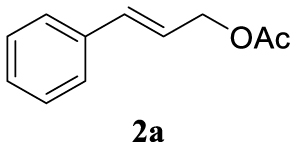

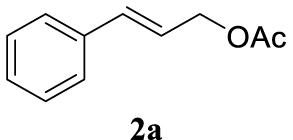

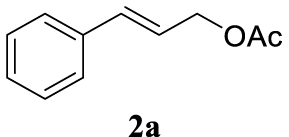

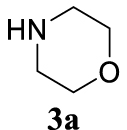

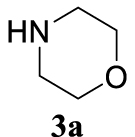

The two selected reactions used for the optimization of the allylation reaction involved cinnamyl acetate 2a. The effect of a basic and strong nucleophile such as morpholine (3a) (Scheme 2a) was compared with the reactivity of a softer one such as 5,5-dimethylcyclohexane-1,3-dione (3h) (Scheme 2b). Based on our previous experience [34], and according to the application-program Central Composite Design+Star [35]1 (see Experimental section for details), the reaction temperature, the reaction time, and the concentration of 1 were chosen as the variables to study (16 overall experiments). The absence of 1 revealed lower conversions of the reaction ( <50%). At the end of the survey, the optimized variables obtained were: 80 °C, 17 h and 5% loading of 1. Thus, palladium(II) chloride (2 mol%), ligand 1 (5 mol%) were added in an ionic liquid as solvent, and after stirring for 1 h, potassium carbonate as base (1.5 equiv), 2a (1 equiv) and 3a (1 equiv) were added and the resulting mixture was left to stand at 80 °C for 17 h (Scheme 2 and Table 1).

Two selected reactions used for optimization.

Optimization of the reaction conditions to synthesize derivatives 4aa and 4aha

| Entry | [Pd] | IL/solvent | T (°C) | Yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization of 4aa | ||||

| 1 | PdCl2 | BMIM BF4 | 80 | 79 |

| 2 | PdCl2 | BMIM BF4 | 25 | — |

| 3 | PdCl2 | BMIM BF4 | 50 | 23 |

| 4 | PdCl2 | BMIM BF4 | 80c | 54 |

| 5 | PdCl2 | —/water | 80 | —d |

| 6 | PdCl2 | BMIM BF4/watere | 80 | —d |

| 7 | PdCl2 | BMIM BF4/MeCNe | 80 | —d |

| 8 | PdCl2 | BMIM NTf2 | 80 | 71 |

| 9 | PdCl2 | BMIM PF6 | 80 | 53 |

| 10 | PdCl2 | BMPyrr NTf2 | 80 | 34 |

| 11 | Pd(OAc)2 | BMIM BF4 | 80 | 55 |

| 12 | Pd(dba)2 | BMIM BF4 | 80 | 94 (A) |

| 13 | Pd(dba)2 | BMIM BF4f | 80 | 67 |

| 14 | Pd(dba)2 | BMIM BF4g | 80 | 70 |

| 15 | Pd(dba)2 | BMIM BF4h | 80 | 70 |

| Optimization of 4ah | ||||

| 16 | Pd(dba)2 | BMIM BF4 | 80 | 96 |

| 17 | Pd(dba)2 | BMIM BF4/watere | 80 | 96 |

| 18 | Pd(dba)2 | BMIM BF4/watere,g | 80 | 96 (B) |

| 19 | Pd(dba)2 | BMIM BF4g | 50 | 66 |

| 20 | Pd(OAc)2 | BMIM BF4 | 80 | 75 |

aReagents and conditions: cinnamyl acetate (1 mmol), morpholine 3a (1 mmol), catalyst [Pd] source (2 mol%) plus ligand 1 (5 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 equiv) and solvent (2 mL/mmol) were stirred at the temperatures and during the reaction times described. bIsolated yields after flash chromatography. cReaction time 8 h. dCinnamyl alcohol was mainly obtained. e1:1 mixture of IL:co-solvent. fTriethylamine was used as base. gReaction performed without base. hReaction run with 1 mL/mmol of 2a.

Study of the scope of the reaction under optimized conditions

aIsolated yields after flash chromatography. In parentheses, the purity (%) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. bIn the presence of 2 equivalents of the allylic acetate. cIsolated as 1:1 mixture of diastereoisomers.

The palladium complex was generated by mixing ligand 1 (5 mol%) and PdCl2 (2 mol%) in BMIM BF4 (1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, 2 mL/1 mmol of 2a), stirring the resulting mixture 1 h at room temperature. The highest conversion and yield corresponded to 80 °C during 17 h despite lower temperatures and reaction times being assayed (Table 1, entries 1–4). The ability of this catalytic system to operate in aqueous media failed in this reaction because a total hydrolysis of the cinnamyl acetate 2a occurred (Table 1, entry 5). At this point, the presence of N-acetylmorpholine was observed in the aqueous solution. The same result was obtained when BMIM BF4 was employed in water and acetonitrile as co-solvent (1:1 mixtures) (Table 1, entries 6 and 7). Next, the nature of the ionic liquid was analyzed, leading to the discovery that the anion has an important role, thus bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide afforded product 4aa in slightly lower chemical yield, whilst tetrafluoroborate derived IL afforded lower yield even (Table 1, compare entries 8 and 9 with entry 1). The employment of 1-butyl-1-methylpyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (BMPyrr NTf2) led to very low conversions in this Tsuji–Trost model reaction (Table 1, entry 10). Pd(dba)2 was the most suitable palladium source in comparison with PdCl2 and Pd(OAc)2 (Table 1, entry 12). This entry will represent the conditions named Method A. Triethylamine instead of potassium carbonate or the absence of base were tested obtaining final coupling product 4aa, but this did not improve the yield obtained in entry 12 (Table 1, entries 13 and 14). The ratio IL/2a was lowered to 1 mL/mmol but the result was not satisfactory (Table 1, entry 15).

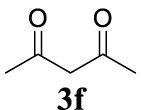

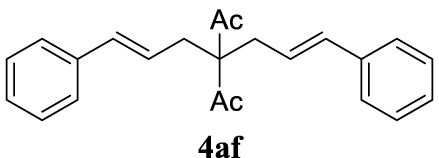

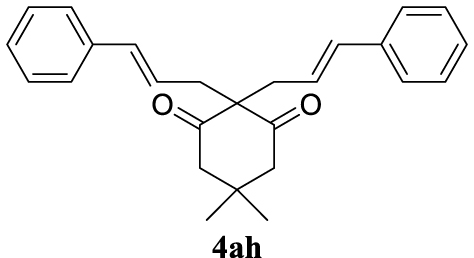

For the optimization of 1,3-diketone 4ah, the conditions described as Method A were assayed obtaining 96% yield of the product (Table 1, entry 16). In addition, a cleaner crude mixture, and with the same quantitative conversion, was observed in the presence of water as co-solvent (Table 1, entry 17). The effect of the presence of K2CO3 was negligible according to the result of entry 18 in Table 1. This entry will represent the conditions named Method B. Lower reaction temperature (50 °C) in the absence of base or using palladium acetate (at 80 °C) as palladium source did not afford very interesting improvements (Table 1, entries 19 and 20, respectively).

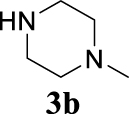

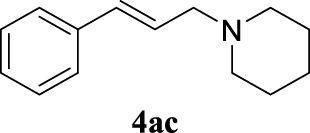

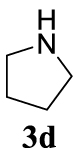

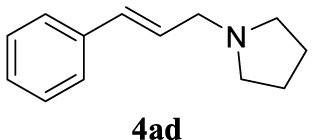

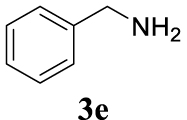

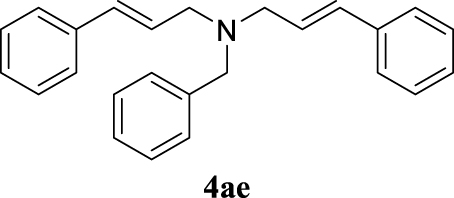

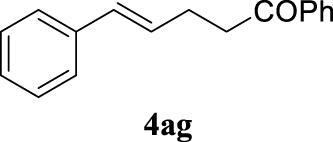

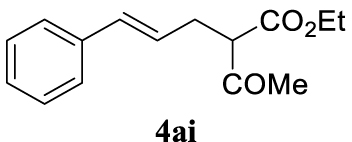

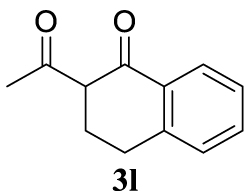

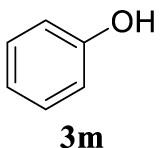

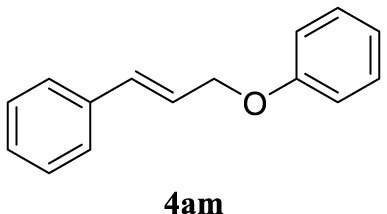

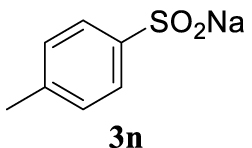

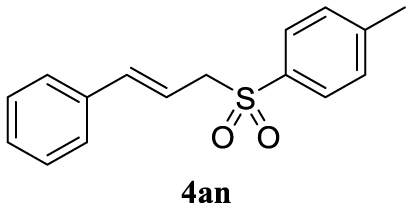

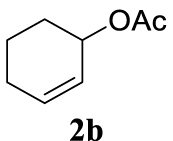

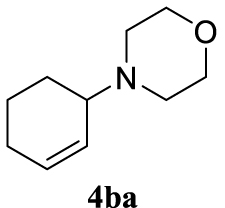

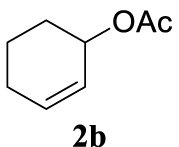

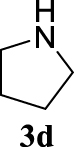

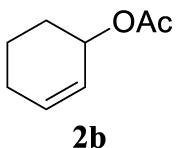

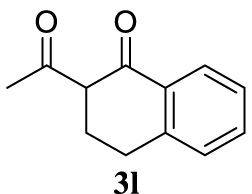

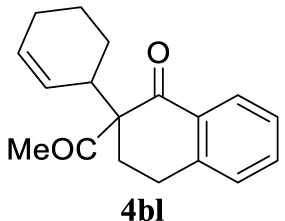

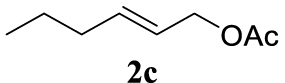

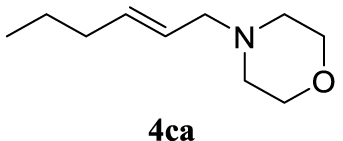

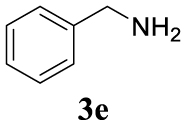

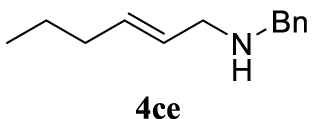

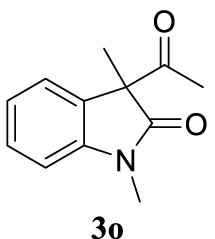

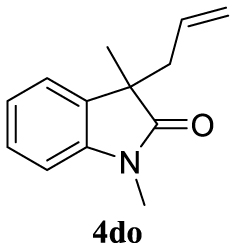

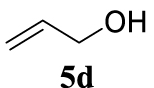

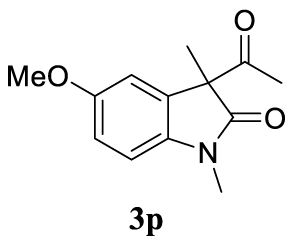

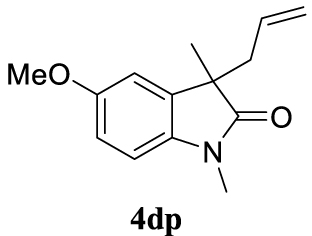

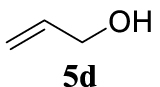

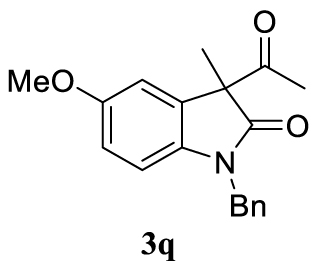

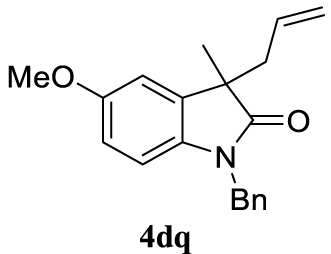

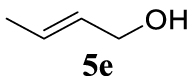

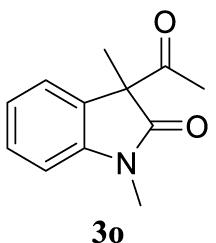

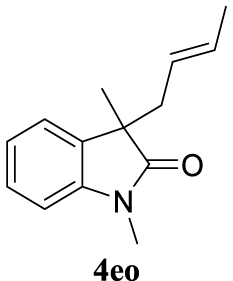

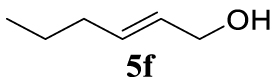

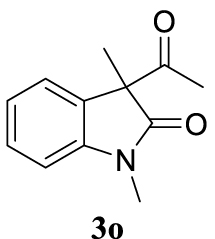

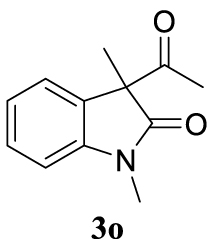

With the best reaction conditions described for basic nucleophiles (Method A) and for carbon nucleophiles (Method B) the general scope for this catalytic system was next evaluated (Table 2). In general, secondary amines (3a–d) afforded the corresponding allylic amines 4aa–4ad in very high yields using Method A (Table 2, entries 1–4). An expected double allylation was detected (compound 4ae) when benzylamine was allowed to react under these conditions (Table 2, entry 5). Next, the battery of 1,3-dicarbonylic compounds (3f–3l) was tested following the Method B obtaining the diallylated compounds 4af–4ah, 4aj and 4ak (Table 2, entries 6–8 and 10–11). In these examples and in the case of amine 4ae, the reaction with 1 equiv of cinnamyl acetate (2a) was surveyed and large amounts of double allylation products were identified by 1H NMR of the crude samples. However, the monoallylation of ethyl 3-oxobutanoate (3i) could be controlled by adding 1.1 equiv of 2a giving very good yield of 4ai (Table 2, entry 9). The monoallylation of 3l (Table 2, entry 12) was also successfully achieved. Phenol (3m) and sodium p-toluenesulfinate (3n) furnished the best chemical yields of 4am and 4an, respectively, under the conditions described for Method A (Table 2, entries 13 and 14). Cyclohex-2-enyl acetate (2b) was appropriate to run either Method A or B affording products 4ba, 4bd, and 4bl in very good to moderated yields (Table 2, entries 15–17). The reaction between the more volatile acetate 2c and morpholine gave product 4ca in good yield (Table 2, entry 18). More inexpensive and easily available allylic alcohols 5d–5g, were next considered as reagent for this Tsuji–Trost transformation. Initially, allyl alcohol 5d was tested using 2-acetyltetralone (3l) employing both Methods A and B but the conversions observed in the crude 1H NMR spectra were very low (not given in Table 2). However, employing the methodology developed by our group [36, 37, 38, 39] dealing with the deacylative allylation (DAA) [40] employing 3-acetyl-3-methyloxindoles 3o–q, the reaction was successful. Under aqueous conditions (Method B), the partial hydrolysis of oxindole 3o occurred although a notable conversion existed (not given in Table 2). In the reaction performed with 3o and alcohol 5d, final product 4do was isolated in 67% yield (Table 2, entry 19). After modification of the allylic alcohol nature and the introduction of several substituents in the 3-acetyl-3-methyloxindole skeleton the scope of this DAA was satisfactorily completed in good to excellent yields (Table 2, entries 20–25). In all these examples, a total n-selectivity versus the analogous branched (b-) one was observed in the 1H NMR spectra of the crude material of each sample.

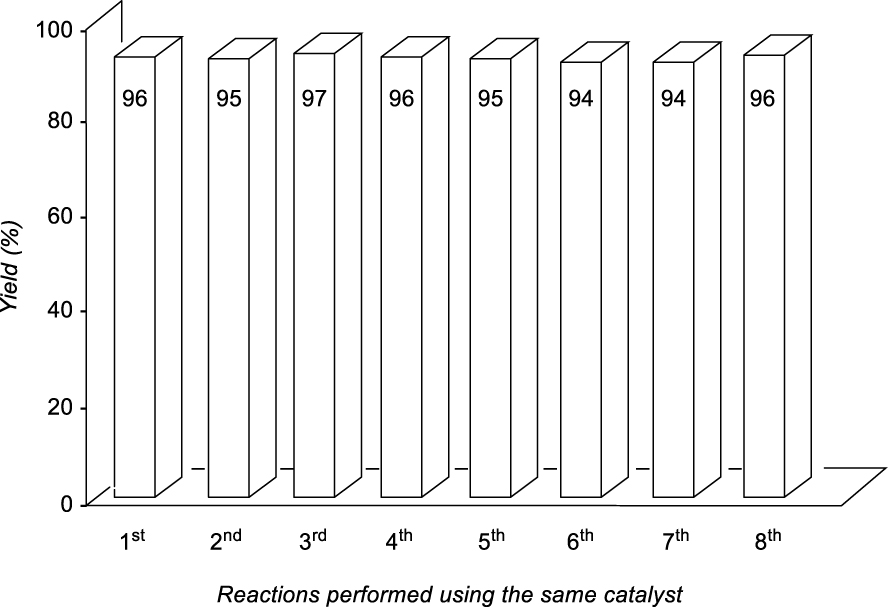

Recycling experiments for the synthesis of product 4ah.

In general, the recovery of the catalyst using ILs is one of the main advantages of these systems, but, in many cases, it was not possible to emulate what is recorded in the literature. For the recycling process of the TSIL-palladium catalytic species we selected the most environmentally benign conditions (Method B) for the formation of the new carbon–carbon bond between 2a (5 mmol scale) and 3h (2 equiv) (Table 2, entry 8, 96%). After completion of each transformation ethyl acetate was added extracting 4ah (this process was repeated once more) and the aqueous-IL phase was used for the next catalytic batch. As depicted in Figure 1, the recovery and reuse of the same catalytic system was extended up to the 8th recycling reaction (at this point we finish this study) exhibiting the same efficiency with the possibility of continuing with more reactions (Figure 1).

The freshly prepared catalytic system was characterized using 1H-, 13C- and 31P-NMR, FTIR, ESI, XPS and TEM. The presence of nanostructured domains along the catalyst surface was noticeable. The catalyst was also studied after the second reaction cycle, after evaporation of the ionic liquid remaining under very low pressure, affording very similar results to those detailed for the pristine catalyst (see Supporting Information).

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have reported the first TSIL-P 1 ligand efficiently applied in the Tsuji–Trost reaction. This catalytic system, formed by the TSIL-P 1 and palladium(0), was robust allowing the recovery and reuse of it up to eight times (possibly more) with total efficiency. The palladium loading is not very high. The combination of IL-TSIL-Pd-water was an appropriate media, in the absence of base, to run the reactions involving the generation of carbon–carbon bonds (Method B). However, Method A was appropriate to perform reactions using N-, O- and S-nucleophiles. In both procedures, a total n-selectivity was achieved covering a wide series of nucleophiles. The reaction temperature and the average reaction times are in the range of the previously published references in this area (Table 3).

Comparison of the recyclability, n-/b-selectivity, conditions and scope described in this work with other similar Tsuji–Trost processes

| Entry | Reference | Extractive agent/solvent | TSIL | [Pd] (mol%) | n-:b-a | Time | T (°C) | Nucleophiles | Catalytic cycles (yield range %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [20] | IL/water | — | 5 | >98:2b | 1–10 min | 400 Wc | C, N, S | Up to 8 (99–98) |

| 2 | [21] | IL/MeCy | — | 1 | >98:2 | 2–9 h | 50–80 | C, O, P | Nrd (—) |

| 3 | [24] | IL/– | — | 2 | >98:2 | 5 h | 40 | C | Up to 5 (38–21) |

| 4 | [28] | Ionogel/– | — | 1 | >98:2 | 7 h | rt | N | Up to 4 (91–12) |

| 5 | [29] | Chitosan SILP/– | — | 4 | >98:2 | 1 h | rt | N | Up to 10 (91–91)e |

| 6 | [30] | IL/– | — | 3 | >98:2 | Flow process | 50 | N | — (—) |

| 7 | [25] | IL/– | — | 10f | — | 30 min | rt | N | Up to 4 (85–85) |

| 8 | [22] | IL/– | — | 2 | — | 5–12 h | rt-50 | C | — (—) |

| 9 | [23] | IL/– | — | 2 | — | 20 min | 80 | C | — (—) |

| 10 | [26] | IL/– | — | 2 | — | 20 min | 80 | C | — (—) |

| 11 | [27] | IL/– | — | 2 | — | 20 min | 80 | C | — (—) |

| 12 | [14] | Surfactant/water | — | 0.1 | >98:2 | 2–37 h | 45 | C, N, O | Up to 4 (86–82) |

| 13 | [15] | Surfactant/water | — | 1 | >98:2 | 18 h | 70 | S | Up to 5 (65–12) |

| 14 | [16] | Extraction/water | — | 3 | >98:2 | 2–12 h | 50–70 | C, N, O, S | Up to 2 (94–93) |

| 15 | [17] | Extraction/MePh | — | — | >98:2 | 20 h | −50 | C | Up to 2 (72–72) |

| 16 | [18] | Extraction/THF(anh) | — | 5 | >98:2 | 14–21 h | rt-68 | N, O | Up to 2 (89–85) |

| 17 | This work | IL/water | 1 | 5 | >98:2 | 17 h | 80 | C, N, O, S | Up to 8 (96–96) |

an-selectivity (normal):b-selectivity (branched) ratio. bFor sulfur nucleophiles the n-:b-selectivity ratio was 1:10. cUnder microwave irradiation. dNo reported (Nr). eThe amount of the starting palladium source was very high (9 mol%). Loss of the palladium catalyst was observed between consecutive cycles arriving to a 0.1 mol% in the 10th batch. fA chiral ligand was added.

4. Experimental section

4.1. General

All commercially available reagents and solvents were used without further purification, only aldehydes were also distilled prior to use. Analytical TLC was performed on Schleicher & Schuell F1400/LS 254 silica gel plates, and the spots were visualized under UV light (𝜆 = 254 nm). Flash chromatography was carried out on handpacked columns of Merck silica gel 60 (0.040–0.063 mm). Melting points were determined with a Reichert Thermovar hot plate apparatus and are uncorrected. The structurally most important peaks of the IR spectra (recorded using a Nicolet 510 P-FT) are listed and wave numbers are given in cm−1. NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker AC-300 or AC-400 and were recorded at 300 MHz for 1H NMR, 75 or 100 MHz for 13C NMR. 1H NMR were recorded using CDCl3 as solvent and TMS as internal standard (0.00 ppm). The following abbreviations are used to describe peak patterns where appropriate: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet or unresolved and br s = broad signal. All coupling constants (J) are given in Hz and chemical shifts in ppm. 13C NMR spectra were referenced in CDCl3 at 77.16 ppm. DEPT-135 experiments were performed to assign CH, CH2 and CH3. Low-resolution electron impact (EI) mass spectra were obtained at 70 eV using a Shimadzu QP-5000 by injection or DIP; fragment ions in m∕z are given with relative intensities (%) in parentheses. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were measured on an instrument using a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (QTOF) and also through the electron impact mode (EI) at 70 eV using a Finnigan VG Platform or a Finnigan MAT 95S. VCD analysis was recorded in a Jasco FVS-6000.

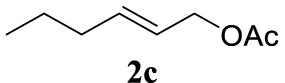

4.2. General synthesis procedure for allyl acetates 2b and 2c

The allylic alcohol (10 mmol) was placed in a round flask under inert atmosphere. Dry dichloromethane (10 mL) was added and the flask placed in an ice bath. Then triethylamine (2.79 mL, 20 mmol) and acetic anhydride (2.26 mL, 10 mmol) were added drop-by-drop. Then, N,N-dimethylaminopyridine (61 mg, 0.5 mmol) dissolved in dry dichloromethane (1 mL) was added to the flask. The reaction was allowed to warm up to room temperature overnight. The reaction was monitored via thin layer chromatography until complete conversion. The organic solvent was washed three times with a saturated solution of NaHCO3 and then with brine. Then, the organic layer was dried with MgSO4 and filtered. The solvent was evaporated to obtain the allylic acetate. These products were used without further purification.

4.2.1. Cyclohex-2-en-1-yl acetate (2b) [41]

Light orange liquid, 2.62 g, 84% yield; 1H NMR (300 MHz) 𝛿: 6.00–5.91 (m, 1H), 5.69 (ddd, J = 10.0, 5.7, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 5.30–5.20 (m, 1H), 2.07–1.97 (m, 5H), 1.80–1.53 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (75 MHz) 𝛿: 132.83, 125.82, 68.23, 28.42, 24.99, 21.56, 18.99.

4.2.2. (E)-Hex-2-en-1-yl acetate (2c) [42]

Light orange liquid, 2.57 g, 87% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 5.70–5.59 (m, 1H), 5.44 (dt, J = 16.7, 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.38 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.97–1.87 (m, 5H), 1.35–1.23 (m, 2H), 0.79 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz): 𝛿 170.8, 136.2, 123.5, 65.3, 34.2, 22.0, 21.1, 13.5.

4.3. General Tsuji–Trost allylation procedure

Method A: bis(dibenzylideneacetone)palladium(0) (5 mg, 8.7 × 10−3 mmol), 1 (10.2 mg, 0.022 mmol) and 1 mL of BMIM BF4 were added to a pressure tube. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature to form the catalytic complex. Then, the allylic acetate (1 mmol), the nucleophile (1 mmol) and K2CO3 (207 mg, 1.5 mmol) were added and the tube was set under inert atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C overnight. Next, the product was extracted from the IL-phase with tert-butyl methyl ether three times. Then, the organic portions were collected and washed with water three times. Finally, the crude was dried with MgSO4, filtered, evaporated and purified by column chromatography (flash-silica-gel) using mixtures of n-hexane:AcOEt eluent.

Method B: bis(dibenzylideneacetone)palladium(0) (5 mg, 8.7 × 10−3 mmol), 1 (10.2 mg, 0.022 mmol), triphenylphosphine (5.8 mg, 0.022 mmol), 1 mL of BMIM BF4 and 1 mL of water were added to a pressure tube. The mixture was stirred for 1 hour at room temperature to form the catalytic complex. Then, the allylic acetate (1 mmol) and the nucleophile (1 mmol) were added and the tube was set under inert atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C overnight. Next, the product was extracted from the IL-phase with tert-butyl methyl ether three times. Then, the organic portions were collected and washed with water three times. Finally, the crude was dried with MgSO4, filtered, evaporated and purified by column chromatography (flash-silica-gel) using mixtures of n-exane:AcOEt eluent.

Recycling procedure to synthesize 4ah: bis(diben- zylidene acetone)palladium(0) (5 mg, 8.7 × 10−3 mmol), 1 (10.2 mg, 0.022 mmol), triphenylphosphine (5.8 mg, 0.022 mmol), 1 mL of BMIM BF4 and 1 mL of water were added to a pressure tube. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature to form the catalytic complex. Then, the allylic acetate 2a (352 mg, 1 mmol) and the nucleophile 3h (140 mg, 1 mmol) were added and the tube was set under inert atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C overnight. Next, ethyl acetate (2 × 2 mL) was used for extracting the final product 4ah and the residual IL mixture was used for the next catalytic batch. This process was repeated up to eight times (see Figure 1).

4.3.1. 4-Cinnamylmorpholine (4aa) [15]

Light yellow oil, 195 mg, 96% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.43–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.33 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.28–7.22 (m, 1H), 6.55 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.28 (dt, J = 15.8, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.82–3.68 (m, 4H), 3.17 (dd, J = 6.8, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 2.60–2.44 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 136.9, 133.5, 128.6, 127.6, 126.4, 126.0, 67.0, 61.5, 53.7.

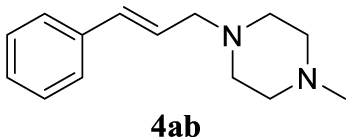

4.3.2. 1-Cinnamyl-4-methylpiperazine (4ab) [43]

Pale yellow oil, 205 mg, 95% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.37 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.26–7.18 (m, 1H), 6.53 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (dt, J = 15.7, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.17 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 2.50 (s, 8H), 2.30 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 137.0, 133.2, 128.7, 127.6, 126.6, 126.4, 61.1, 55.2, 53.2, 46.1.

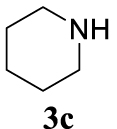

4.3.3. 1-Cinnamylpiperidine (4ac) [44]

Pale orange oil, 150 mg, 75% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.41–7.35 (m, 2H), 7.30 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (dt, J = 15.8, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.13 (dd, J = 6.8, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 2.45 (s, 4H), 1.68–1.57 (m, 4H), 1.46 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 137.1, 132.9, 128.6, 127.5, 127.1, 126.4, 61.9, 54.6, 26.0, 24.4.

4.3.4. 1-Cinnamylpyrrolidine (4ad) [45]

Pale yellow oil, 127 mg, 68% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.41–7.18 (m, 5H), 6.56 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (dt, J = 15.8, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 3.34 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H),2.67 (s, 4H), 1.89–1.80 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 137.0, 128.7, 127.7, 126.5, 58.3, 53.9, 23.6.

4.3.5. (E)-N-Benzyl-N-cinnamyl-3-phenylprop-2-en-1-amine (4ae) [43]

Colorless oil, 318 mg, 94% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.47–7.24 (m, 15H), 6.60 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 2H), 6.37 (dt, J = 15.9, 6.5 Hz, 2H), 3.74 (s, 2H), 3.35 (dd, J = 6.5, 0.9 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 139.4, 137.3, 132.8, 129.1, 128.6, 128.3, 127.6, 127.4, 127.0, 126.4, 58.1, 56.1.

4.3.6. (1E,6E)-1,7-Diphenylhepta-1,6-diene-4,4-diyl diacetate (4af) [15]

Colorless oil, 245 mg, 74% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.30 (ddd, J = 15.3, 9.2, 3.9 Hz, 10H), 6.50 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 6.09–5.85 (m, 2H), 2.89 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 2.20 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 205.8, 136.9, 134.4, 128.6, 127.7, 126.3, 123.4, 70.9, 34.7, 27.4.

4.3.7. (E)-1,5-Diphenylpent-4-en-1-one (4ag) [45]

Colorless oil, 236 mg, quantitative yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 8.07–7.96 (m, 2H), 7.65–7.55 (m, 1H), 7.55–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.18 (m, 5H), 6.51 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (dt, J = 15.8, 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.79–2.64 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 199.4, 137.5, 137.0, 133.1, 130.9, 129.2, 128.6 (d, J = 11.7 Hz), 128.1, 127.1, 126.1, 38.3, 27.6.

4.3.8. 2,2-Dicinnamyl-5,5-dimethylcyclohexane-1,3-dione (4ah) [46]

Colorless prisms, mp 145–147 °C (Hx:EtOAc), 370 mg, quantitative yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.81–7.11 (m, 10H), 6.47 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 2H), 6.18–5.93 (m, 2H), 2.74 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 4H), 2.60 (s, 4H), 0.98 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 209.0, 137.0, 134.5, 128.8, 128.3, 127.5, 126.3, 123.9, 68.5, 52.3, 38.4, 30.7, 28.7.

4.3.9. (E)-Ethyl 2-acetyl-5-phenylpent-4-enoate (4ai) [47]

Colorless oil, 233 mg, 95% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.49–7.11 (m, 5H), 6.46 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.25–5.91 (m, 1H), 4.22 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1.5H), 3.59 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 0.5H), 2.93–2.63 (m, 2H), 2.24 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 171.6, 169.3, 137.1, 134.2, 132.8, 128.8 (d, J = 13.6 Hz), 127.5 (d, J = 7.0 Hz), 126.3 (d, J = 4.2 Hz), 125.8, 123.8, 63.9, 61.6, 59.7, 35.8, 31.6, 29.3, 27.2, 14.3.

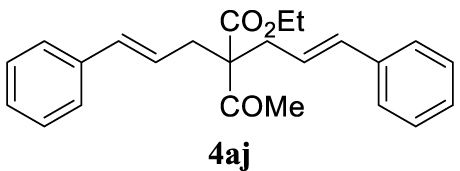

4.3.10. (E)-Ethyl 2-acetyl-2-cinnamyl-5-phenylpent-4-enoate (4aj)

Pale yellow oil, 318 mg, 88% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.38–7.16 (m, 10H), 6.47 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 2H), 6.10–5.91 (m, 2H), 4.24 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.84 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.3 Hz, 4H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 204.3, 171.6, 137.1, 134.3, 128.7, 127.6, 126.3, 123.8, 63.9, 61.6, 35.9, 27.3, 14.3; IR (neat) 𝜈 (cm−1): 1732, 1700, 1294, 1281, 986, 969, 857, 739; MS (EI) m∕z (%): 362 (M+, 1), 344 (26), 289 (10), 288 (40), 245 (23), 205 (17), 204 (18), 200 (20), 199 (100), 197 (16), 171 (16), 169 (11), 157 (57), 141 (22), 129 (16), 128 (22), 117 (71), 115 (53), 91 (50), 43 (22); HRMS (ESI): calculated for C24H26O3: 362.1882; found 362.1885.

4.3.11. Dimethyl 2,2-dicinnamylmalonate (4ak)

Pale yellow oil, 283 mg, 78% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.47–7.15 (m, 1H), 6.49 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 6.28–5.92 (m, 1H), 3.77 (s, 1H), 2.87 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 171.3, 137.2, 134.3, 128.7, 127.6, 126.3, 124.0, 58.5, 52.6, 36.8; IR (neat) 𝜈 (cm−1): 1732, 1447, 1198, 740, 692; MS (EI) m∕z (%): 364 (M+,6), 304 (17), 215 (55), 213 (26), 206 (18), 205 (100), 183 (23), 155 (13), 153 (11), 147 (13), 141 (14), 128 (21), 117 (79), 116 (15), 115 (87), 91 (31); HRMS (ESI): calculated for C23H24O4: 364.1675; found 364.1676.

4.3.12. 2-Acetyl-2-cinnamyl-3,4-dihydronaphtalen-1(2H)-one (4al) [48]

Colorless oil, 298 mg, 98% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 8.11 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.17 (m, 7H), 6.45 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.22–6.07 (m, 1H), 3.18–3.03 (m, 1H), 2.99–2.75 (m, 4H), 2.18 (s, 3H), 2.11 (ddd, J = 13.8, 10.6, 5.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 205.6, 197.3, 143.9, 137.1, 134.1, 132.1, 129.0, 128.6, 128.0, 127.5, 126.9, 126.3, 124.6, 64.1, 38.4, 29.5, 27.2, 25.8.

4.3.13. (Cinnamyloxy)benzene (4am) [15]

Colorless oil, 172 mg, 82% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.50–7.24 (m, 1H), 7.06–6.96 (m, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (dd, J = 16.0, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 4.74 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 158.9, 136.6, 133.1, 129.6, 128.7, 128.2, 126.7, 124.7, 121.0, 114.9, 68.7.

4.3.14. 1-(Cinnamylsulfonyl)-4-methylbenzene (4an) [15]

Colorless oil, 271 mg, quantitative yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.77 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.38–7.23 (m, 7H), 6.41 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.17–6.04 (m, 1H), 3.95 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 2.44 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz): 144.8, 139.0, 135.9, 135.6, 132.5–131.75 (m), 129.7, 129.0–128.1 (m), 126.6, 115.3, 60.5, 21.7.

4.3.15. 4-(Cyclohex-2-en-1-yl)morpholine (4ba) [15]

Colorless oil, 160 mg, 96% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 5.87–5.79 (m, 1H), 5.70–5.61 (m, 1H), 3.71 (ddd, J = 5.4, 3.9, 1.7 Hz, 4H), 3.15 (dtd, J = 7.5, 5.0, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 2.64–2.51 (m, 4H), 1.98 (dt, J = 10.5, 4.1 Hz, 2H), 1.84–1.74 (m, 2H), 1.54 (ddd, J = 11.4, 6.9, 3.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 130.7, 128.7, 67.6, 60.8, 49.2, 25.4, 23.3, 21.6.

4.3.16. 1-(cyclohex-2-en-1-yl)pyrrolidine (4bd) [49]

Colorless oil, 41 mg, 27% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 5.88–5.69 (m, 2H), 2.89 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 2.63 (td, J = 9.1, 2.4 Hz, 4H), 1.98 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 1.77 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 4H), 1.60–1.47 (m, 2H), 1.20 (d, J = 22.1 Hz, 1H), 0.98 (d, J = 24.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz): 129.8, 128.2, 59.5, 50.9, 28.1, 25.4, 23.5, 21.1.

4.3.17. 2-acetyl-2-(cyclohex-2-en-1-yl)-3,4-dihydronaphtalen-1(2H)-one (4bl)

Light yellow oil and as a 1:1 mixture of diastereoisomers, 121 mg, 45% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz): 8.05 (td, J = 7.7, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (td, J = 7.4, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 5.86–5.68 (m, 1H), 5.26 (dd, J = 10.3, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 4.30 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 0.34H), 3.68–3.54 (m, 0.50H), 3.40–3.27 (m, 0.60H), 3.25–3.08 (m, 1H), 2.88–2.75 (m, 1H), 2.59–2.40 (m, 1H), 2.17 (s, 1.72H), 2.11 (s, 1.33H), 2.06–1.89 (m, 3H), 1.80 (dd, J = 12.9, 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.60 (dt, J = 12.9, 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.35 (dd, J = 27.3, 10.2 Hz, 3H), 0.92–0.80 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz): 204.9 (d, J = 102.7 Hz), 197.1 (d, J = 20.5 Hz), 144.5 (d, J = 12.8 Hz), 134.0 (d, J = 9.6 Hz), 132.8 (d, J = 10.2 Hz), 130.9 (d, J = 30.1 Hz), 129.9 (d, J = 8.1 Hz), 129.0 (d, J = 6.4 Hz), 127.9 (d, J = 5.2 Hz), 127.5 (s), 126.6 (d, J = 7.3 Hz), 126.2 (s), 68.2 (d, J = 11.0 Hz), 40.7 (d, J = 1.9 Hz), 26.6 (d, J = 36.8 Hz), 26.4 (d, J = 17.0 Hz), 25.2 (d, J = 8.9 Hz), 24.7 (d, J = 40.0 Hz), 23.9 (d, J = 39.2 Hz), 22.5 (d, J = 27.7 Hz). IR (neat) 𝜈 (cm−1): 2930, 1705, 1670, 1599, 1453, 1433, 1357, 1300, 1288, 1227, 1212, 1175, 1156, 1143, 1120, 1071, 919, 892, 779, 758, 740, 720; LRMS (EI) m∕z (%): 268 (M+, 1%), 226 (21), 225 (100), 149 (13), 115 (10), 81 (12), 43 (13); HRMS (ESI): calcd. for C18H20O2 268.1463; found 268.1471.

4.3.18. (E)-4-(hex-2-en-1-yl)morpholine (4ca) [50]

Colorless oil, 105 mg, 62% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 5.59 (dt, J = 14.3, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.53–5.40 (m, 1H), 3.80–3.60 (m, 4H), 2.93 (dd, J = 6.7, 0.9 Hz, 2H), 2.42 (s, 4H), 2.00 (dd, J = 14.2, 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.45–1.33 (m, 2H), 0.88 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 135.2, 125.8, 67.0, 61.4, 53.6, 34.5, 22.6, 13.7.

4.3.19. (E)-N-Benzylhex-2-en-1-amine (4c3)

Colorless oil, 105 mg, 62% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.54–7.15 (m, 5H), 5.76–5.45 (m, 2H), 3.92–3.79 (m, 0.57H), 3.74–3.54 (m, 1.05H), 3.24 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 0.43H), 3.06 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1.97H), 2.05 (dd, J = 13.6, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 1.43 (dd, J = 14.6, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 134.1, 129.1, 128.5, 128.3, 128.2, 127.3, 126.8, 57.4, 55.6, 34.7, 22.6, 13.8; IR (neat) 𝜈 (cm−1): 2958, 2928, 2360, 2341, 1770, 1759, 1456, 971, 908. 730, 697, 648; MS (EI) m∕z (%): 189 (M+, 21), 147 (16), 108 (14), 91 (100), 73 (23), 55 (19), 41 (13); HRMS (ESI): calculated for C13H19N: 189.1517; found: 189.1516.

4.3.20. 3-Allyl-1,3-dimethylindolin-2-one (4do) [51]

Colorless oil, 135 mg, 67% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.26 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.44 (ddt, J = 17.2, 10.1, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 5.10–4.86 (m, 2H), 3.19 (s, 3H), 2.51 (dd, J = 7.3, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 1.36 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 180.3, 143.3, 133.7, 132.8, 127.8, 122.9, 122.4, 118.7, 108.0, 48.5, 42.5, 26.2, 22.8.

4.3.21. 3-Allyl-5-methoxy-1,3-dimethylindolin-2-one (4dp) [51]

Colorless oil, 176 mg, 76% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 6.90–6.63 (m, 3H), 5.44 (ddt, J = 17.6, 10.1, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.99 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (s, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.16 (s, 3H), 2.67–2.39 (m, 2H), 1.35 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 179.9, 156.1, 136.8, 135.2, 132.6, 118.8, 111.7, 110.8, 108.2, 55.9, 48.8, 42.6, 26.3, 22.9.

4.3.22. 3-Allyl-1-benzyl-5-methoxy-3-methylindolin-2-one (4dq) [36]

Colorless oil, 298 mg, 97% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.40–7.15 (m, 6H), 6.81 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.74–6.44 (m, 2H), 5.65–5.27 (m, 1H), 5.13–4.84 (m, 3H), 4.77 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 2.57 (qd, J = 13.5, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.42 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 179.7, 155.7, 135.9, 135.6, 134.8, 132.5, 128.5, 127.3, 127.1, 118.7, 111.5, 110.5, 109.1, 55.6, 48.6, 43.5, 42.3, 23.1.

4.3.23. (E)-3-(But-2-en-1-yl)-1,3-dimethylindolin-2-one (4eo) [40]

Colorless oil, 202 mg, 94% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.30–7.20 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.13 (m, 0.48H), 7.04 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1.38H), 6.81 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1.40H), 5.86 (ddd, J = 17.0, 10.4, 8.6 Hz, 0.15H), 5.58 (ddd, J = 17.1, 10.2, 9.0 Hz, 0.13H), 5.46–5.34 (m, 0.48H), 5.17–5.01 (m, 0.85H), 4.89 (d, J = 10.5 Hz, 0.10H), 3.23–3.15 (m, 4.18H), 2.59 (ddd, J = 28.2, 21.7, 10.6 Hz, 0.48H), 2.41 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 0.87H), 1.51 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1.57H), 1.46 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.39 (s, 0.25H), 1.34 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1.39H), 0.97 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 0.49H), 0.67 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 0.42H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 180.6, 178.8, 144.1, 143.2, 139.2, 138.6, 134.0, 130.7, 129.4, 127.9, 127.8, 127.7, 124.9, 124.2, 123.9, 123.6, 123.2, 123.0, 122.9, 122.5, 122.3, 122.3, 116.9, 115.7, 108.0, 107.9, 107.8, 107.8, 51.3, 51.2, 45.9, 44.8, 41.4, 40.6, 36.7, 35.5, 29.8, 26.3, 26.2, 26.1, 26.0, 24.8, 22.6, 22.2, 21.6, 17.9, 15.4, 15.0.

4.3.24. (E)-3-(Hex-2-en-1-yl)-1,3-dimethylindolin-2-one (4fo) [40]

Colorless sticky oil, 204 mg, 84% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.29–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 5.36 (dt, J = 13.9, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (dt, J = 15.0, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 3.18 (s, 3H), 2.44 (dd, J = 7.3, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 1.81 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.35 (s, 3H), 1.23–1.17 (m, 3H), 0.73 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 180.6, 143.7, 134.9, 134.0, 127.7, 124.0, 123.0, 122.3, 107.9, 48.8, 41.6, 34.7, 26.2, 22.5, 13.5.

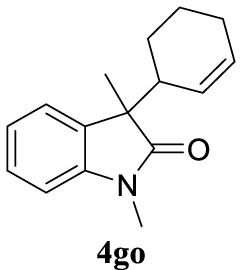

4.3.25. 3-(Cyclohex-2-en-1-yl)-1,3-dimethylindolin-2-one (4go) [40]

Pale yellow oil, 231 mg, 96% yield; 1H NMR (400 MHz) 𝛿: 7.28–7.16 (m, 4.27H), 7.02 (qd, J = 7.5, 0.9 Hz, 1.96H), 6.82 (dd, J = 7.7, 4.2 Hz, 1.82H), 5.81 (dt, J = 22.8, 6.3 Hz, 2.11H), 5.59 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 0.76H), 5.32 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 0.66H), 3.21 (s, 3H), 3.20 (s, 3.15H), 2.71–2.62 (m, 1.70H), 1.84 (ddd, J = 34.0, 15.4, 7.6 Hz, 6.25H), 1.64–1.32 (m, 13.53H), 0.91 (ddd, J = 21.8, 19.3, 10.7 Hz, 4.24H); 13C NMR (101 MHz) 𝛿: 180.5, 143.7, 133.6, 133.6, 130.7, 129.2, 127.7, 126.8, 125.9, 123.8, 123.5, 122.3, 107.9, 107.6, 51.1, 51.0, 43.5, 42.9, 26.2, 26.1, 25.1, 25.0, 24.5, 24.4, 22.5, 21.8, 21.4, 20.9.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (projects CTQ2016-81893REDT, and RED2018-102387-T) the Spanish Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad, Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER, EU) (projects CTQ2016-76782-P, CTQ2016-80375-P, CTQ2017-82935-P and PID2019-107268GB-I00), the Generalitat Valenciana (IDIFEDER/2021/013) and the University of Alicante (VIGROB-050, VIGROB-068, UADIF17-42 and UAUSTI16-02). Dr. D. Lledó thanks the Spanish Ministerio de Educación for the fellowship FPU15/00097.

1This is a useful response surface methodology to build a second-order model for the response variable commonly employed in the design of the experiment. It uses fractional factorial design in the response surface model. In this design, the center points are augmented with a group of axial points called star points. With this design, first-order and second-order terms can be estimated quickly.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0