1. Introduction

The rapid eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems driven by the collective impacts of population growth, urbanization, and contemporary agricultural methods has become a major concern worldwide [1]. The frequent release of large amounts of colored wastewater into natural streams exacerbates the situation, causing negative impacts on both the environment and human health [2]. This type of wastewater is typically generated by industries that use dyes to achieve the desired coloration of their products. They include several sectors such as food, paper, rubber, textiles, plastics, and so on [3, 4]. Currently, the utilization of dyes is witnessing a significant surge, with approximately 10,000 different dyes in existence and an annual production exceeding 0.7 million metric tons [5]. The release of synthetic dyes into natural streams elevates water toxicity, raises chemical oxygen demand levels, and diminishes light penetration, thereby obstructing photosynthetic processes [6]. As a result, the presence of dyes in natural streams can have severe ecological consequences [7, 8]. At the same time, access to high-quality water is limited, and it is considered a valuable resource that has to be absolutely protected [9]. Therefore, it has become increasingly essential to treat wastewater and remove pollutants, ensuring their safe disposal, and prevent the contamination of natural water bodies [10].

Furthermore, the swift advancement of society has led to the production of large amounts of low-value materials considered worthless. These materials are often regarded as waste, and their disposal has become a significant challenge [11]. Additionally, some materials found in nature have little to no practical use. In this context, various industrial and agricultural wastes have been tested as biosorbents for dye removal from effluents, such as coffee grounds [8], date palm petiole (DPP) [12], palm fronds [13], date stones [14, 15], sugar-extracted spent biomass [16], apricot stones [17], rice husk [18], olive stones [19], banana peel [20], hazelnut shell [21]…, and so on.

Dyes persist in water for extended periods and are challenging to be treated because of their low biodegradability [22]. Conventional wastewater treatment technologies, including chemical precipitation [23], electrochemical oxidation [24], coagulation [25], membrane filtration [26], ion exchange [27], photocatalysis process [28] reverse osmosis [29], and liquid extraction [30], are often impractical for large-scale industrial applications [31]. Moreover, these technologies have numerous drawbacks, including the generation of toxic byproducts, low effectiveness, high energy consumption, and the use of expensive reagents [32, 33].

The adsorption process is considered one of the most cost-effective and eco-friendly physicochemical techniques for dye removal from wastewater [34, 35]. It entails transferring dyes from the water phase to the surface of a solid adsorbent. Compared to other methods, adsorption offers several advantages. For instance, it is a straightforward process that does not necessitate specialized equipment or substantial energy input [36]. Moreover, it can achieve high removal efficiency without generating toxic byproducts. Additionally, it can utilize a range of low-cost and easily accessible adsorbents, including activated carbon, clay minerals, agricultural waste, and biosorbents, making it a sustainable and environmentally friendly option [2].

Several researchers have investigated the use of various agricultural products and byproducts for removing dyes from solutions [37, 38, 39]. Residues, often consisting of lignocellulosic materials, possess a natural ability to adsorb waste chemicals such as dyes and cations from water. This capability arises from Coulombic interactions between the substrates, facilitating physical absorption [40]. These materials are renewable agricultural wastes that are abundantly available at little to no cost [40]. However, most of the recent studies have tried to physicochemically modify these materials in order to improve their structural, textural, and surface chemistry properties and therefore their ability in removing dyes from aqueous [41, 42, 43] solutions.

In the open literature, there are few studies on the use of DPP material for the preparation of activated carbons [44, 45, 46]. These reports have focused on using such materials as adsorbents with minimal processing (washing, drying, grinding), thereby reducing production costs not only by utilizing inexpensive raw materials but also by eliminating energy costs associated with thermal treatments. As far as the authors are aware, there is no work that has employed DPP without further thermal treatment as an adsorbent.

The authors believe that the current work will provide new insights into the utilization of raw waste materials for treating wastewater. The clear advantage of this method, compared to others, is its low cost and eco-friendly aspect.

This study represents another contribution to our ongoing research on the removal of water contaminants using untreated agricultural byproducts without any chemical treatment of the adsorbent. Thus, it aims to assess the efficiency of DPP in removing Bezaktiv Marine S-BL (SBL) dye from textile effluent. The interaction between the adsorbent and the adsorbate was assessed through an optimization process, considering factors affecting adsorption such as adsorbent dose, pH, contact time, and initial concentration. Furthermore, adsorption kinetics and isotherms were comprehensively investigated through the use of common models.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Biosorbent preparation

Date palm petioles were collected from local farms in Adrar (Algeria). The biomaterial was subjected to several wash cycles with hot distilled water to remove dust and subsequently air-dried for two weeks. Then, the dried sample underwent grinding and sieving to produce particles within the diameter range of 250–500 μm. This fraction of DPP was utilized in subsequent experiments and processing.

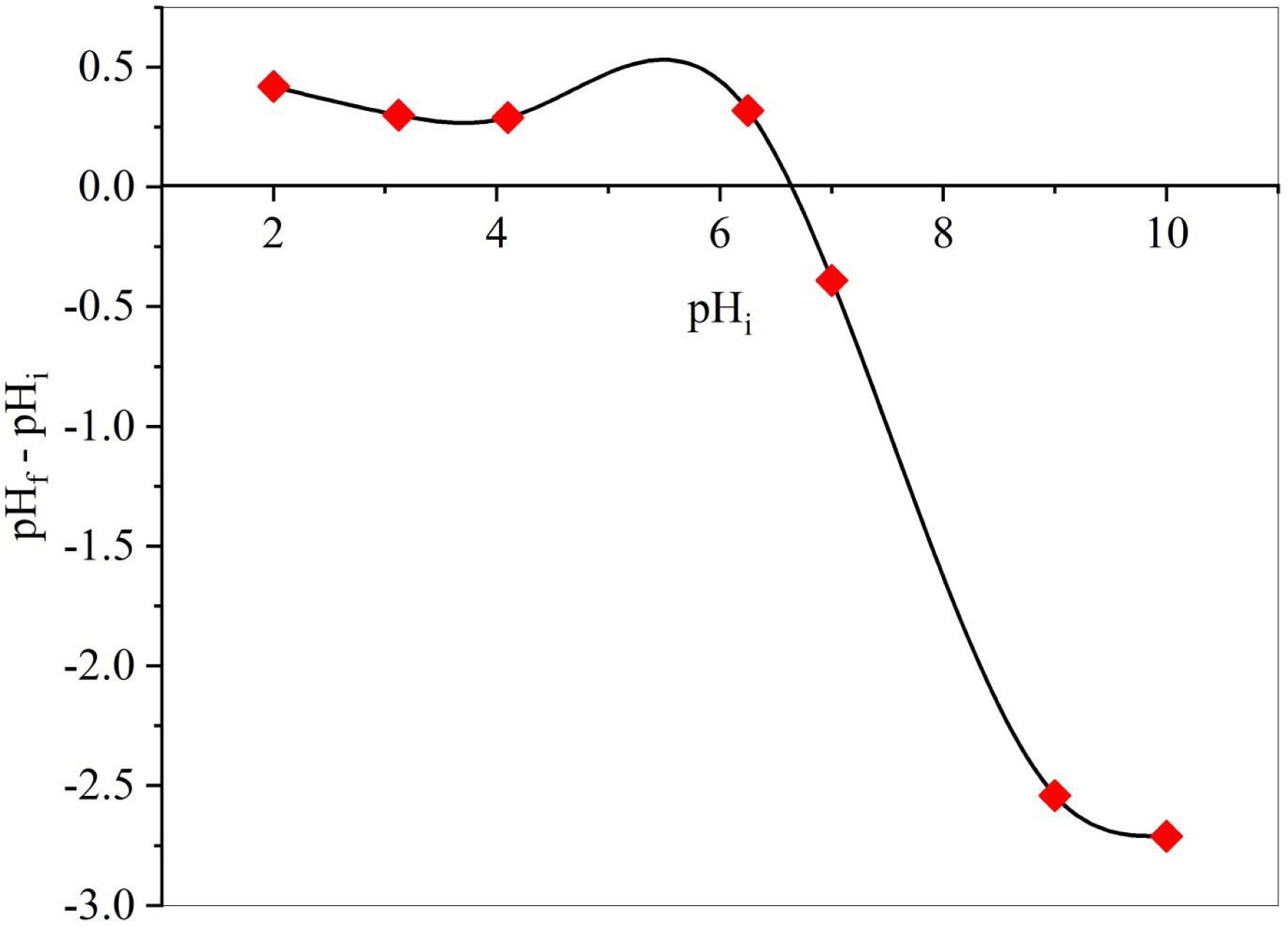

The point of zero charge (pHPZC) of the DPP was determined using the pH drift method [35]. A series of flasks containing 25 mL of a 0.1 mol⋅L−1 KNO3 aqueous solution at pH values of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 were prepared. The initial pH (pHi) was adjusted using 0.1 mol⋅L−1 KOH or HNO3 aqueous solutions. Next, 10 mg of DPP was added to each sample. The dispersions were stirred for 24 h at room temperature, and the final pH (pHf) of the solution was measured and plotted against pHi. The pHPZC was determined from the plot of pHf = f(pHi), where the pH at which the curve intersects the bisector of the axes is taken as the pHPZC of the carbon.

2.2. Adsorption studies

A stock solution of SBL at a concentration of 500 mg/L was prepared by dissolving 500 mg of SBL in 1 L of distilled water and diluted as required to obtain the desired concentrations.

Batch adsorption experiments were carried out in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, which were agitated on a shaker at 350 rpm for a specified contact time. The suspensions were subsequently filtered, and the remaining concentrations of SBL in the supernatant solutions were determined using a Cary 60 Series spectrophotometer. Absorbance calibration curves were recorded against the concentration of the SBL solution at a maximum wavelength of 599 nm. The selected parameter ranges, including initial SBL concentration, adsorbent concentration, and pH, were based on literature reports on SBL adsorption using other agricultural residues, facilitating a comparison of adsorption performance.

2.2.1. Effect of time, pH, and adsorbent dose on adsorption of SBL onto DPP

Adsorption kinetic experiments were performed to assess the effect of contact time on SBL removal. For this purpose, 50 mg of DPP was agitated in 25 mL of SBL solution (50 mg⋅L−1) at 25 °C for contact times ranging from 10 to 180 min. Aqueous solutions were separated from the adsorbent by centrifugation. The adsorbed amount at a given time t, Qt (mg/g), was calculated using the following equation [36]:

| (1) |

The effect of DPP dose was assessed for biosorbent doses varying between 0.4 and 2 g⋅L−1. Moreover, the effect of pH on SBL removal was examined within the range of 2 to 12. These effects were evaluated for an initial dye concentration of 50 mg/L and at equilibrium. All tests were conducted in triplicate.

2.2.2. Equilibrium adsorption isotherms

The adsorption performance of DPP was assessed through isotherm experiments, where 10 mg of DPP was suspended in 25 mL of aqueous solutions containing various pollutant concentrations (CSBL = 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160, 180, 200 mg/L). The suspensions were stirred for 24 h at 150 rpm to ensure equilibrium. Once equilibrium was achieved, 5 mL aliquots were withdrawn from the suspension and centrifuged at 8000 rpm to remove any suspended particles. The concentrations of residual dye in the supernatant solutions were measured using a spectrophotometer after appropriate dilution.

2.2.3. Thermodynamic studies

The influence of temperature on the sorption of SBL onto DPP was examined to determine the nature of the adsorption process. The adsorption tests were conducted at four temperatures: 15 °C, 25 °C, 35 °C, and 45 °C. The experimental results were utilized to determine thermodynamic functions, specifically standard enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), and free energy (ΔG), calculated using Equations (2) and (3) [37, 38]:

| (2) |

| (3) |

2.2.4. Adsorption models

In order to select an appropriate model for fitting the experimental data of SBL adsorption onto DPP, the investigation focused on analyzing the kinetic mechanism by applying the pseudo-first-order [47], pseudo-second-order [48], and intraparticle diffusion models [49] to the experimental data. Moreover, the experimental isothermal data were analyzed to ascertain the distribution of the adsorbate between the solid and liquid phases at various equilibrium concentrations, aiming to better understand the uptake process. Thus, the models of Freundlich [50] and Langmuir [51] were employed to assess the dye adsorption parameters onto DPP. With further analysis of the Langmuir equation, the Langmuir isotherm is characterized by a dimensionless separation factor RL given by [52]:

| (4) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Adsorption kinetics

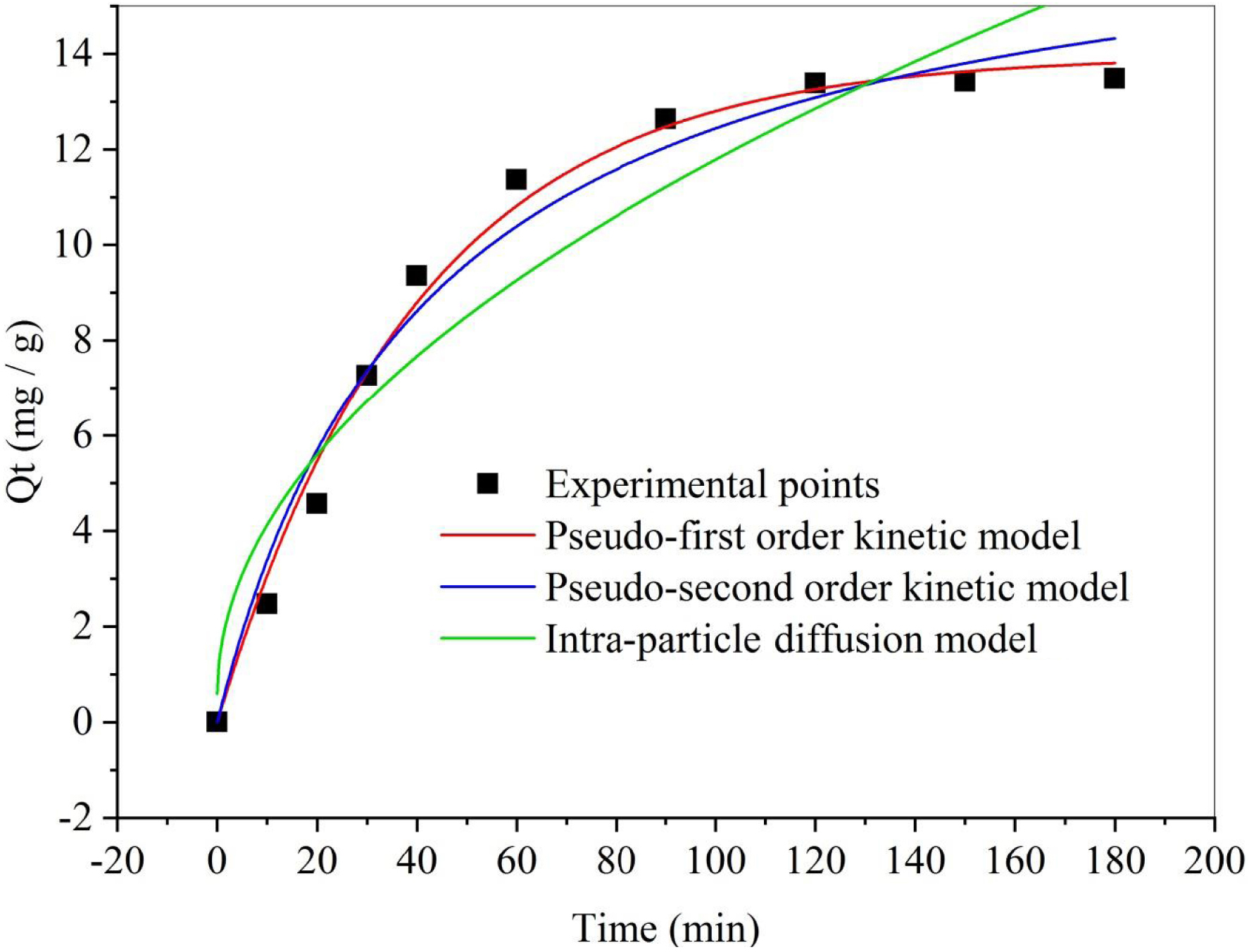

To determine the equilibrium time, the impact of contact time on dye biosorption was investigated. Figure 1 illustrates the adsorption of SBL on DPP over time. The results show that the SBL biosorption increases with time and reaches equilibrium after 120 min. The efficiency of the biosorbent’s removal increases quickly in the initial stage (0–100 min) due to the abundance of active binding sites on the biomass [53]. During the second stage (100–120 min), biosorption becomes less efficient and reaches saturation. This could be attributed to the interaction of SBL involving the functional groups located on the biosorbent surface and intercellular accumulation [54]. Based on the findings, a shaking duration of 120 min was opted for subsequent biosorption experiments.

Effect of contact time on removal capacity (T = 25 °C, C = 50 mg/L, V = 25 mL, m = 50 mg).

To elucidate the kinetics of the adsorption reactions, focusing on order and rate constants, a kinetic study was undertaken. The mechanism controlling SBL biosorption by DPP was explored by analyzing the experimental data fitting to the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and intraparticle diffusion kinetic models. The results of the kinetic parameters are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1. Based on the assessment of both the correlation coefficients (R2) and the estimated adsorbed amounts at equilibrium (Qe) values, it is evident that SBL adsorption onto DPP is more adequately described by the pseudo-first-order model. This suggests that surface adsorption interactions may be the rate-determining step, and the adsorption capacity likely correlates with the number of active sites available on the biosorbent [55].

Adsorption kinetic model parameters

| Parameters | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order | k1 (min−1) | 0.0248 |

| Qe (mg⋅g−1) | 13.96 | |

| R2 | 0.987 | |

| Pseudo-second-order | k2 (g⋅mg−1⋅min−1) | 0.0013 |

| Qe (mg⋅g−1) | 17.66 | |

| R2 | 0.978 | |

| Intraparticle diffusion | Kdiff (min−1) | 1.1198 |

| C | 0.5873 | |

| R2 | 0.913 | |

3.2. Effect of biosorbent dose

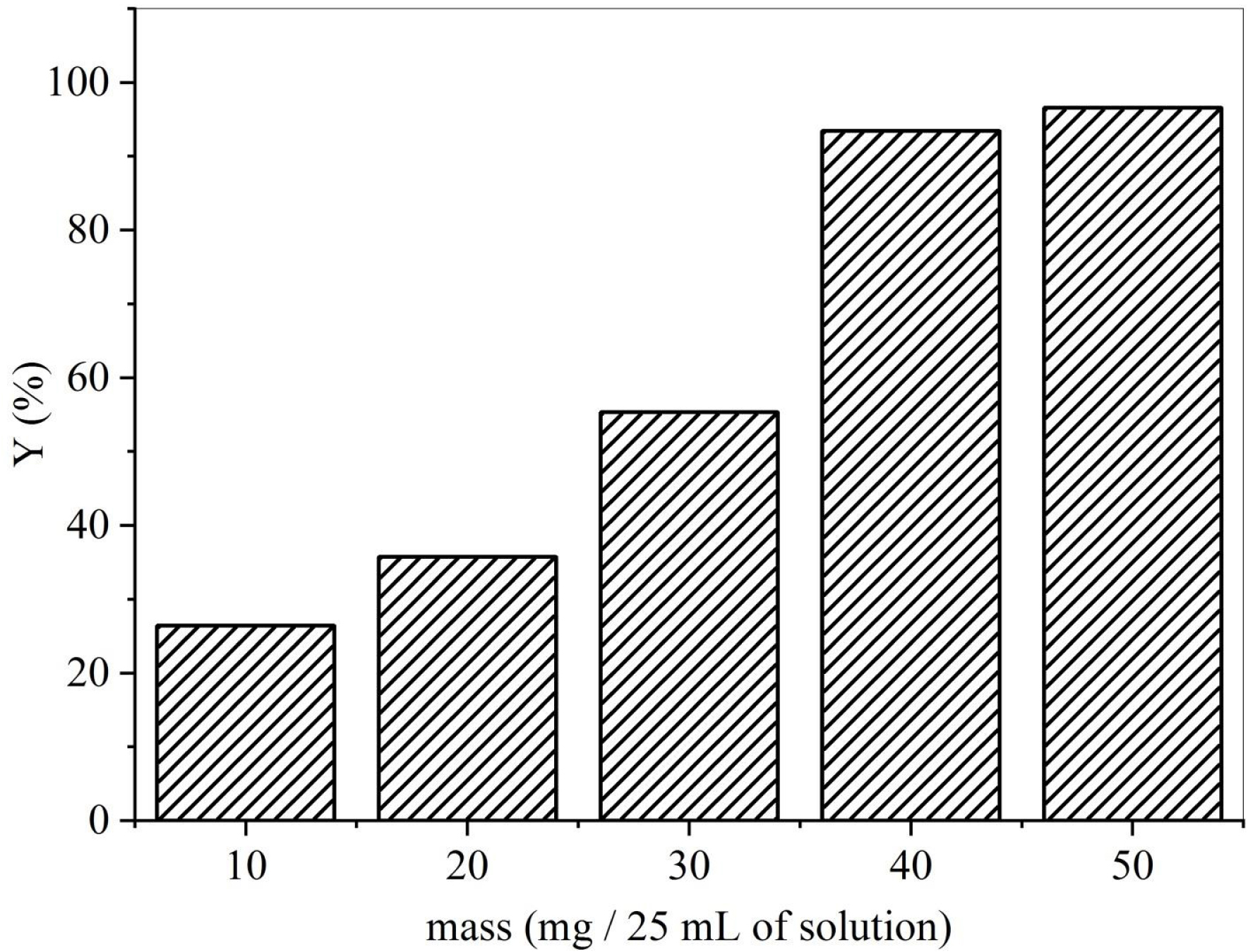

The adsorbent dose is a vital parameter that dictates the capacity of an adsorbent for a given initial concentration of the adsorbate under particular operating conditions. To identify the optimal adsorbent mass for maximum removal efficiency, the effect of varying the mass of DPP on the adsorption of SBL at a constant adsorbate concentration was investigated. The results indicated that SBL uptake increased as the dose increased (Figure 2). Specifically, values of the removal rate Y (%) (Y = (c1 − cf)/ct) increased from 26% to 96% as the adsorbent dose increased from 10 to 50 mg/25 mL. This behavior is due to the presence of more active adsorption sites for increased doses that can react with SBL molecules. A similar pattern was noted in a study on the removal of methylene blue from an aqueous solution using fruit kernels [56] and with calcium-rich biochars for removing amoxicillin [57].

Adsorbent dose effect on biosorption capacity (Qe; T = 25 °C, C = 50 mg/L, V = 25 mL, t = 120 min).

3.3. Solution pH

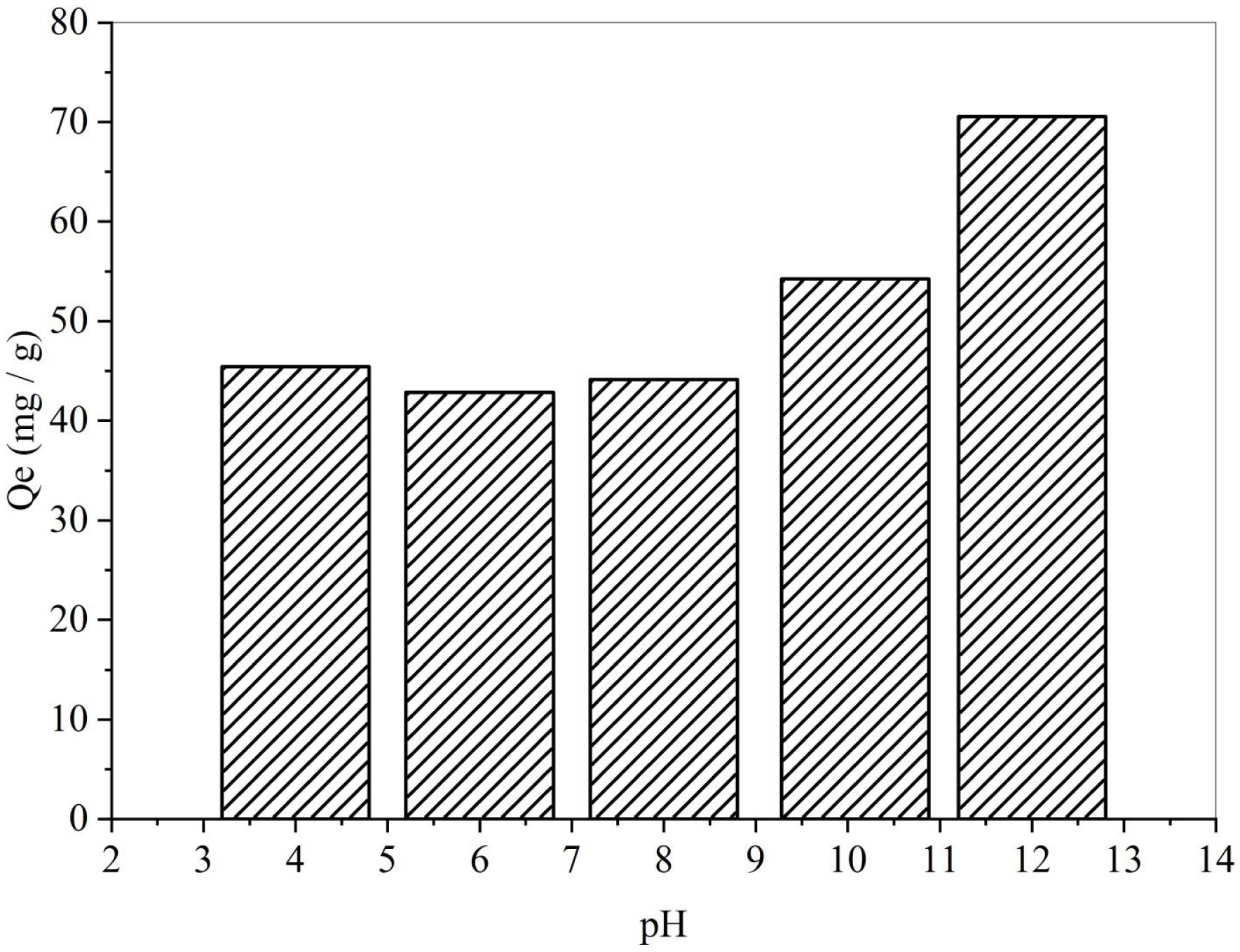

Solution pH plays a crucial role in adsorption processes as it directly influences the surface charge and the characteristics of ionic species in the adsorbates [35]. The pH effect was investigated across a range of 4 to 12, with the evolution of Qe values shown in Figure 3. The SBL adsorption capacity decreased as the pH increased from 4 to 6. This decrease in adsorption capacity can be attributed to the surface charge of the adsorbent, which leads to electrostatic repulsion between the adsorbent surface and negatively charged adsorbate molecules. At higher pH levels, the surface of the adsorbent becomes negatively charged through the deprotonation of functional groups, thereby enhancing the attraction between the adsorbent and SBL molecules and increasing the adsorption capacity. The observed trend in SBL removal with changing pH can be elucidated by considering the point of zero charge (pHPZC) of the adsorbent. There is a correlation between pHPZC (Figure 4) and biosorption capacity, which varies with pH and aids in understanding the behavior of suspended biomaterials in solution [58, 59]. As depicted in Figure 3, SBL removal is favorable at pH values greater than pHPZC (5.5), where the surface charge of the biosorbent becomes negative (pH > pHPZC). In this pH range, the positively charged SBL molecules will be removed through electrostatic interactions. Relatively similar behavior was observed for Bezaktiv Orange S-RL 150 removal by a biochar derived from palm flower stalk waste [39].

Effect of solution pH on removal capacity (Qe; T = 25 °C, C = 50 mg/L, V = 25 mL, t = 120 min, m = 50 mg).

Experimental determination of point of zero charge.

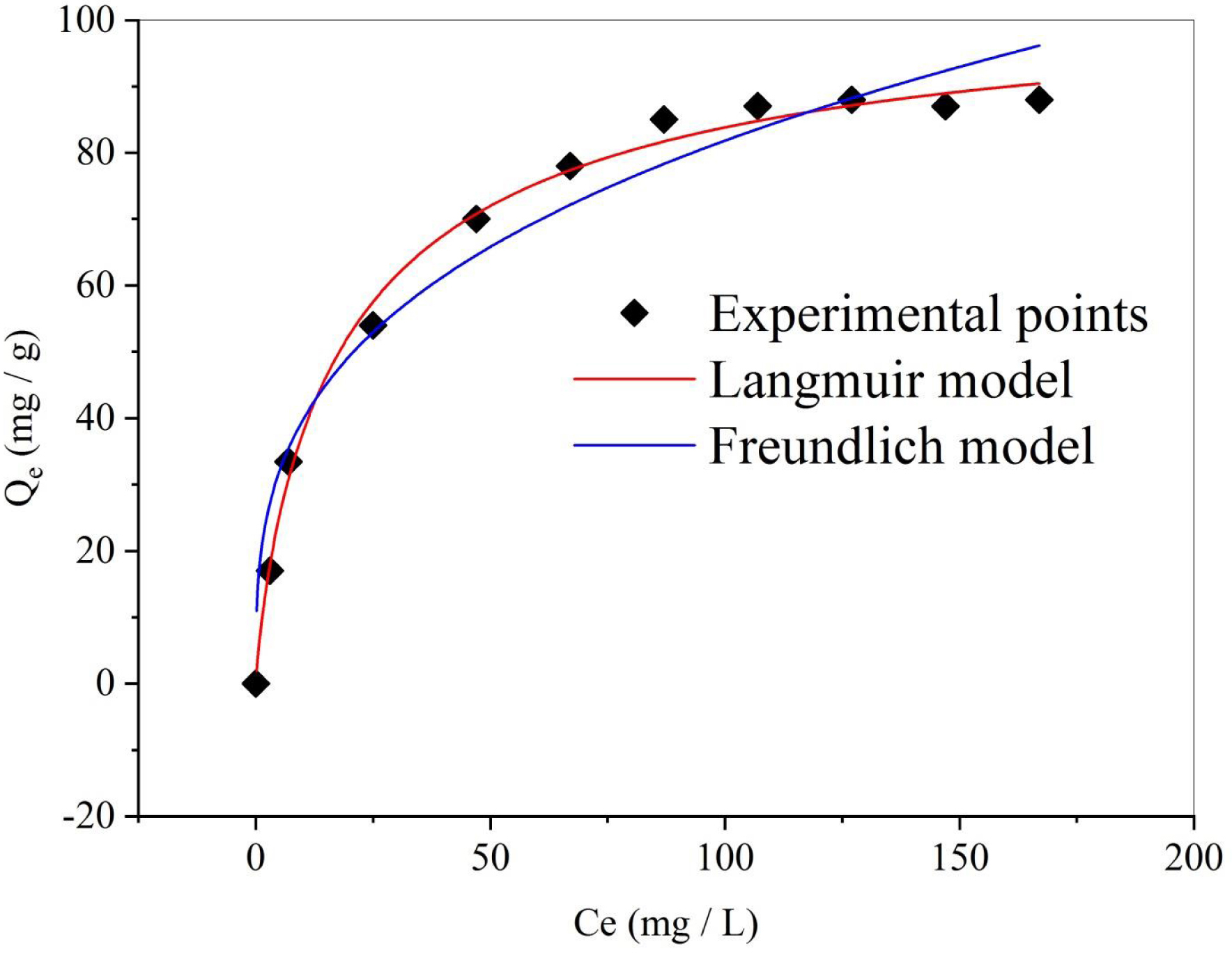

3.4. Isotherm adsorption studies

The adsorption isotherms describe the relationship between the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of the adsorbent and the concentration of the adsorbate in an aqueous solution at equilibrium [60, 61]. The SBL adsorption isotherm onto DPP is presented in Figure 5. The isotherm reveals that as the initial concentration of SBL increases, the biosorbed quantity rises until reaching a saturation point, indicating that all active sites on the adsorbent surface are occupied. This suggests homogeneous adsorption of SBL through ionic interactions facilitated by the negatively charged surface of the adsorbent [44]. The isotherm belongs to type L according to the Giles classification, indicating strong interaction between the adsorbed molecules and the surfaces of the adsorbent [62].

Adsorption isotherms of SBL onto DPP (T = 25 °C, m = 50 mg, V = 25 mL, t = 120 min, pH = 10).

The adsorption data were fit to two different isotherm models, namely Freundlich and Langmuir, to characterize the adsorption of dye solutions onto DPP biochar. These models offer a deeper understanding of the adsorption process, which is crucial to evaluating or designing an adsorption system [63]. The modeling outcomes are shown in Figure 5 and Table 2. By comparing the R2 values (Table 2), the Langmuir model more accurately describes the adsorption of SBL. The dimensionless equilibrium constant (RL) values for the Langmuir isotherm were lower than 1 (0.064–0.552), indicating that the adsorption process is spontaneous. Furthermore, the parameter 1/n in the Freundlich isotherm, which indicates the adsorption intensity of SBL dye on the applied adsorbent, had values below unity (0.314), suggesting that the adsorption process is favorable and implies that significant adsorption can occur even at high dye concentrations. The Langmuir isotherm model was opted for assessing the maximum adsorption capacity, indicating the adsorbent’s complete monolayer coverage. The adsorption capacity, denoted as Qmax and measuring the maximum sorption capacity at full monolayer coverage, had a value of 106.17 mg/g.

Adsorption isotherm model parameters

| Parameters | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | kL | 0.081 |

| Qmax (mg⋅g−1) | 106.17 | |

| R2 | 0.992 | |

| Freundlich | KF | 19.25 |

| 1/n | 0.314 | |

| R2 | 0.945 | |

As expected, DPP biochar exhibited a higher Qmax value than numerous other materials reported in the scientific literature. Palm frond biochar was used for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions, presenting an adsorption capacity of 70.87 mg/g [13], which is lower than the value obtained in this work. The DPP-derived activated carbon presented a sorption capacity of 53.76 mg/g for indigo carmine [46]. Date palm fiber had shown a maximum removal capacity of 18.45 mg/g for Ni ion and 16.15 mg/g for Cd ion elimination [64]. Therefore, the DPP biochar can serve as a promising adsorbent for wastewater treatment.

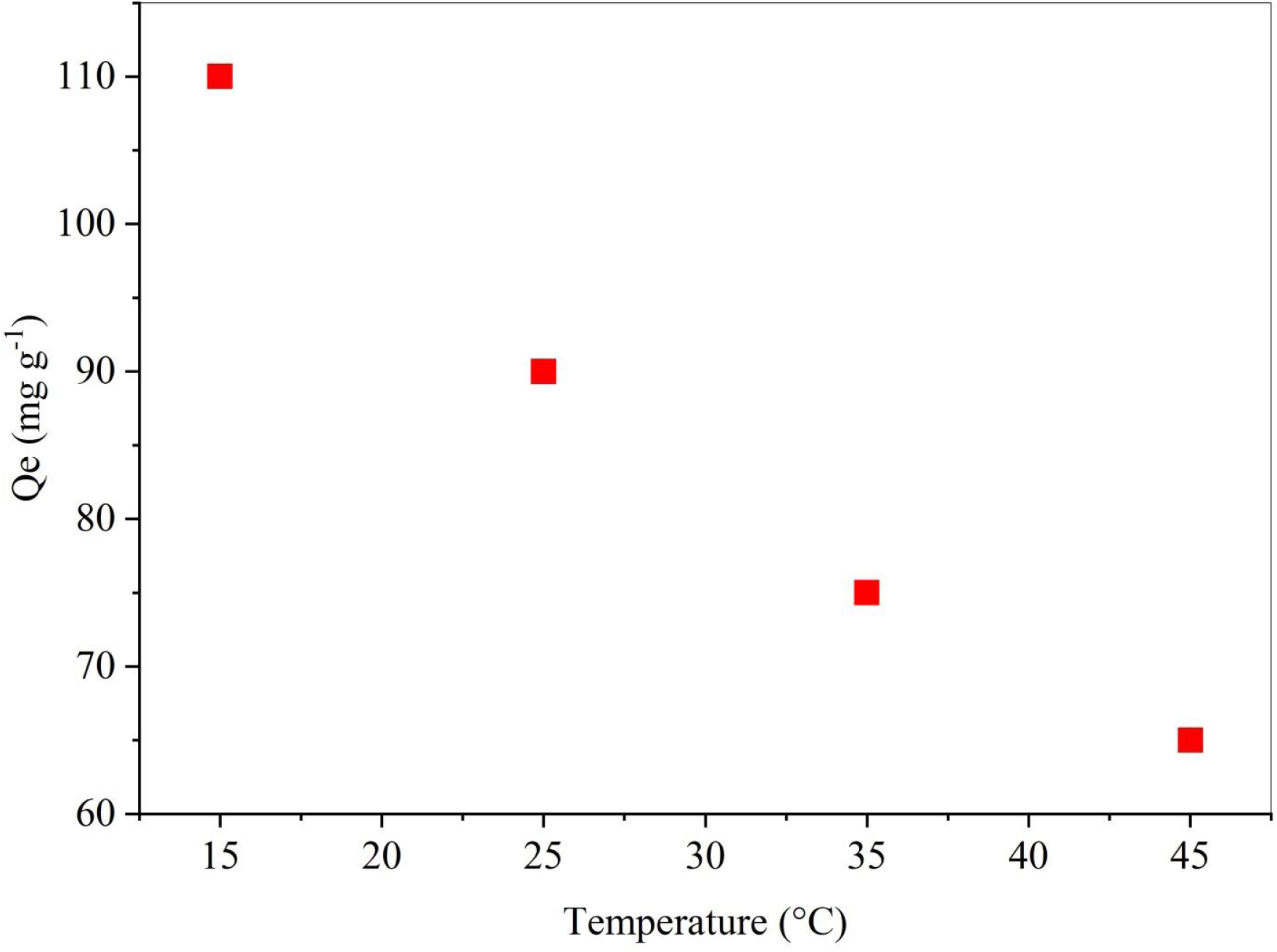

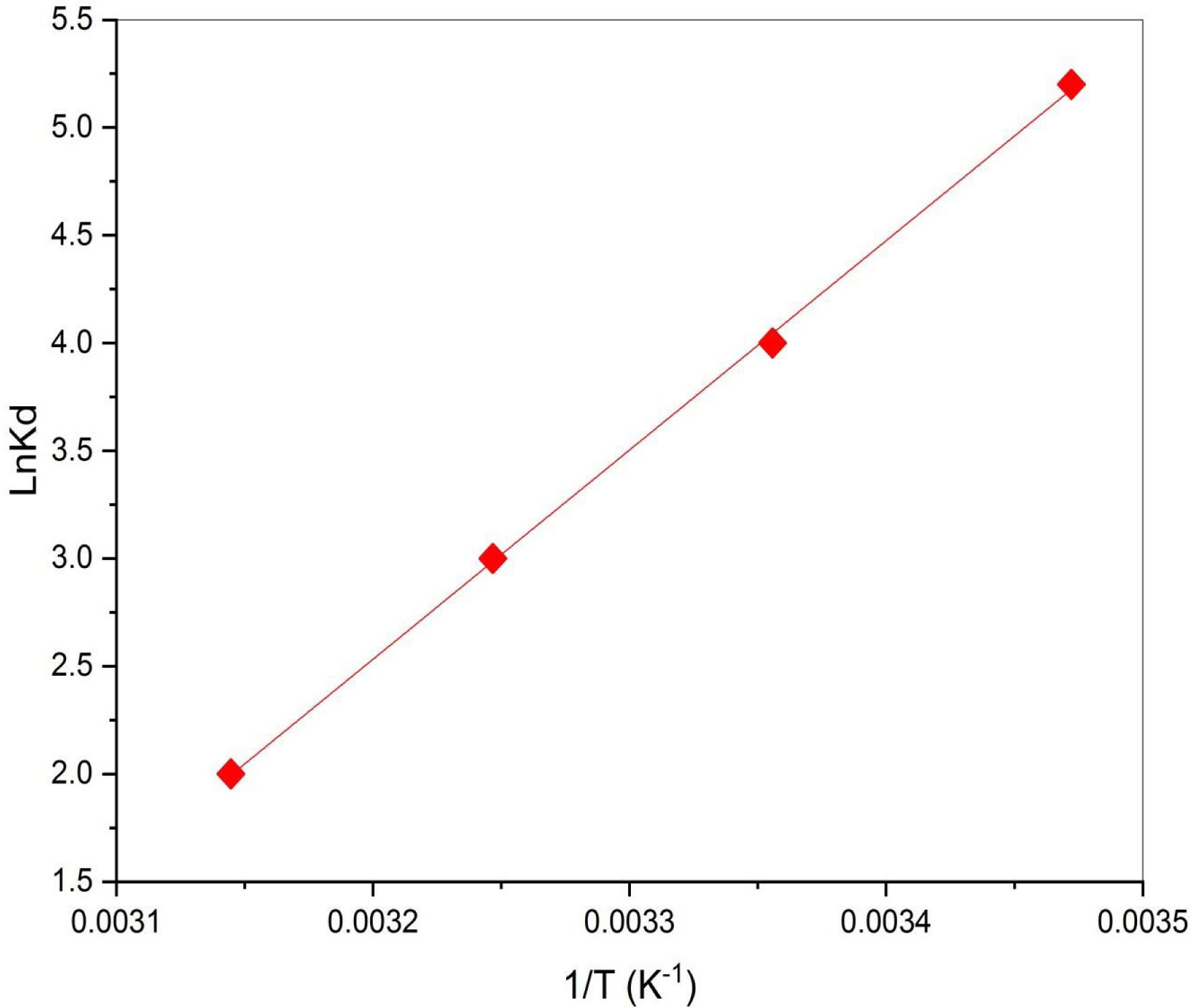

3.5. Thermodynamic studies

Temperature exerts a notable influence on the sorption process, which can be explained through thermodynamic parameters [16]. The thermodynamic functions evaluated from the variation of distribution coefficient (Kd) in Figure 7 are listed in Table 3. The overall ΔG values are negative, varying between −12.451 and −5.287 kJ/mol for temperature levels of 15–45 °C, demonstrating that the biosorption process occurred spontaneously. The negative value of ΔH (−80.76 kJ/mol) indicates the exothermic nature of the biosorption process. This fact was confirmed by the higher amount of dye removal observed at lower temperatures (Figure 6). Furthermore, the negative value of ΔS (−237.38 J⋅mol−1⋅K−1) indicates decreased randomness at the solid/solution interface, with no significant changes occurring in the internal structure of the adsorbent during the adsorption process [65]. The ΔH and ΔS values of DPP–SBL are comparable to those reported by Aichour et al. [44] when investigating methyl orange removal by DPP-derived biochar.

Adsorption thermodynamic parameters

| Temperature (K) | ΔG (kJ⋅mol−1) | ΔH (kJ⋅mol−1) | ΔS (J⋅mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 288 | −12.451 | −80.760 | −237.38 |

| 298 | −9.910 | ||

| 308 | −7.682 | ||

| 318 | −5.287 |

Temperature effect on SBL removal by DPP (C = 200 mg/L, m = 50 mg, V = 25 mL, t = 120 min, pH = 10).

Plot of lnKd versus 1/T.

4. Conclusion

This study primarily aims to determine the feasibility of using DPP biomass as a cost-effective adsorbent for dye-contaminated wastewater. The sorption of SBL dye by DPP waste reveals significant influences of sorbent dose, initial concentration, pH, and contact time on SBL removal. The dye concentration emerged as the most crucial factor affecting both adsorption capacity and color removal efficiency. The evaluation of adsorption isotherms revealed that the Langmuir isotherm, with a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.993, best fit the experimental data. Additionally, the monolayer adsorption capacity of the dye on DPP was determined to be 106.17 mg/g. The pseudo-first-order kinetic model, with an R2 value of 0.987, was also identified as the most suitable model for describing the adsorption process. The results of kinetic, equilibrium, and thermodynamic studies supported the feasibility of utilizing DPP biomass as an efficient adsorbent for dye removal. Utilizing this locally sourced biomass could help alleviate the financial burden associated with valorizing agricultural byproducts for water treatment applications.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Data availability statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0