1 Introduction

In 1972 Fujishima and Honda [1] were the first to observe the photoelectrochemical water splitting at illuminated TiO2 photoanodes. Since then, semiconductor photocatalysis has found growing interest due to its widespread applications in many fields, especially in solar energy conversion and environmental remediation. Basic principles of semiconductor photocatalysis have been well documented in the literature [2–5]. When a semiconductor is irradiated by light with energy matching or greater than its bandgap, conduction band electrons (e–) and valence band holes (h+) are generated. These excited charge carriers are mobile and capable of initiating many chemical redox reactions at the semiconductor surface. The excited electrons and holes, however, tend to recombine quickly, dissipating the energy as heat. Therefore, the photocatalytic activity of semiconductors is largely dependent on the competition between the surface charge-carrier transfer and the electron-hole recombination. Thus, in order to carry out effective semiconductor photocatalysis, two essential criteria need to be satisfied: (1) optimum light absorption by the semiconductor; and (2) sufficiently long-lived photoexcited charge carriers (e–/h+) to enable the occurrence of the desired reactions.

Among various semiconducting metal oxides, TiO2 has proven to be the most promising photocatalyst for a wide range of applications because of its high photoreactivity, relatively low cost, nontoxicity, chemical and biological inertness, and longterm stability against photocorrosion. Like other semiconductors, TiO2 bears the inherent drawback of a rapid electron–hole (e––h+) recombination, and its photocatalytic activity is thus limited. To improve the photoefficiency of TiO2 photocatalysis, the e––h+ recombination rate must be reduced. In addition, TiO2 is a solid-state material, thus its photocatalytic activity is unavoidably influenced by many factors such as particle size and distribution, surface area, crystal and surface structure. Hence, the strategy to design and prepare TiO2-based photocatalysts with high photoefficiency has become a major topic leading to intensive research in the field. In this context, our work has been focused on the improvement of TiO2 photocatalyst nanoparticles by Fe(III)-doping and platinization, respectively, which are two typical approaches employed to inhibit the fast recombination of photoexcited electrons and holes.

This review addresses novel synthetic pathways for the preparation of Fe(III)-doped TiO2 and platinized TiO2, respectively, recently developed in the authors' laboratories. An attempt is made to establish the correlation between the activity of TiO2 photocatalysts (Fe(III)-doped or platinized) and their physical properties, especially their structural characteristics. Based on the experimental observations, novel mechanistic principles for photocatalysis, i.e. the antenna mechanism and the so-called deaggregation concept, have been developed [6–11].

2 Fe(III)-doped TiO2 colloids

In the past decade, several research groups have carried out interesting work with Fe(III)-doped TiO2. For example, Litter and Navio [12] investigated the mechanism of the Fe(III)-doping of the titania matrix. Zhang et al. [13] found an Fe(III) effect dependent on particle size. Bockelmann et al. [14] observed marked spectral response upon Fe(III) addition to TiO2. Our contribution to this area has been to develop a new method to prepare Fe(III)-doped TiO2 exhibiting enhanced photocatalytic activity.

2.1 Novel synthetic approach

In general, Fe(III)-doped TiO2 has been synthesized via ‘wet’ chemistry, i.e. hydrolysis of a Ti-precursor in the presence of a Fe(III)-containing aqueous solution as shown in Fig. 1a [12–14]. Since the reaction system is fed with the Ti and Fe precursors present as different solution phases, the Fe/Ti ratio is unavoidably changed during addition of the Ti-precursor to the solution of the Fe precursor, particularly so in the initial stage of particle growth. There is little doubt that such an effect influences the local distribution of iron in the particles formed and hence the photocatalytic efficiency. Therefore, it is desirable to mix both Fe (III) and Ti (IV) precursors prior to hydrolysis. This is the principle of our new synthesis (see Fig. 1b). The advantage of the novel preparation for the enhancement in photocatalytic activity was verified by the quantum yield measurements for the formation of formaldehyde during the photocatalyzed oxidation of methanol in aqueous solution.

Preparations of Fe(III)-doped TiO2: (a) conventional method; and (b) novel method.

2.2 Photocatalytic methanol oxidation

TiO2-based photocatalysis is initiated by UV(A) light irradiation. For the photocatalyzed oxidation of methanol, a simple model is proposed as follows [15].

Charge-carrier generation

| (1) |

Charge-carrier recombination

| (2) |

Production of hydroxyl radicals

| (3) |

Interfacial charge transfer

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

As seen from Eqs. (5)–(7), the production rate of HCHO should be proportional to that of the hydroxyl radical, •OH, which plays a vital role in photocatalysis. Therefore, the quantum yield of the photocatalytic HCHO formation can be used as an indicator for the •OH production, and hence can be used to compare different photocatalysts [15].

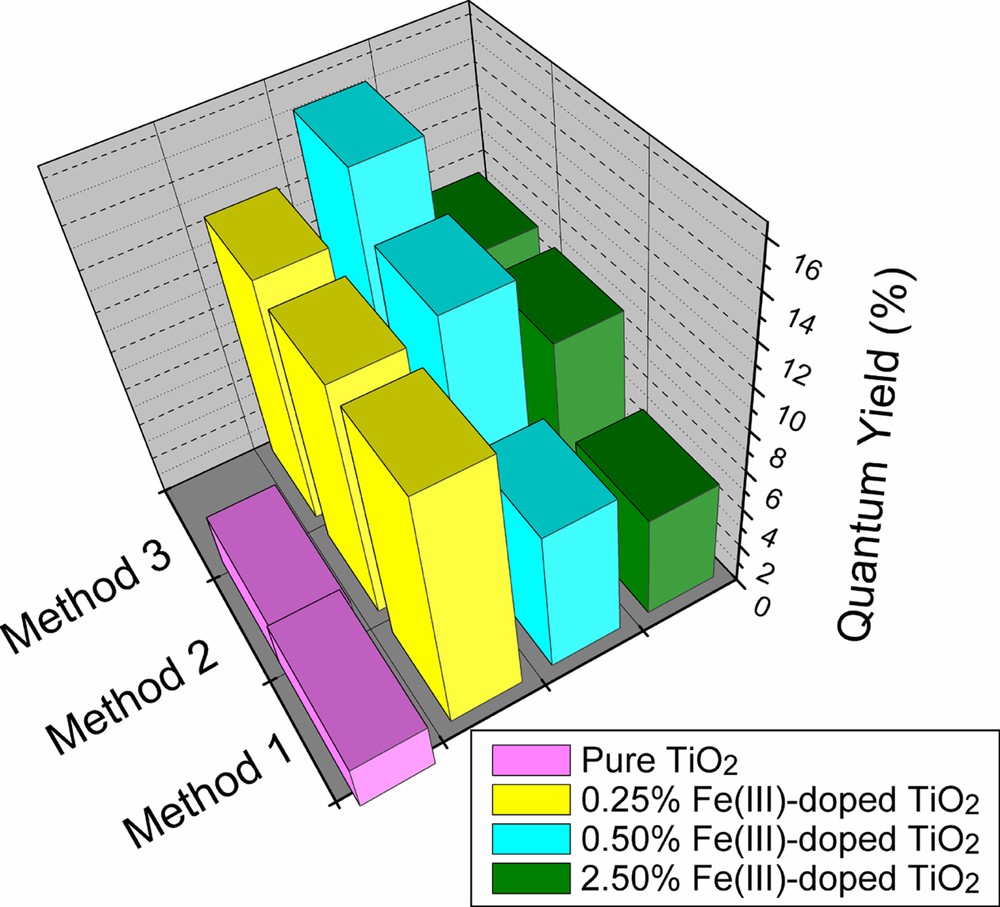

Fig. 2 shows the values of the quantum yield of formaldehyde formation, ϕHCHO, determined for nanocrystalline pure TiO2 and iron-doped TiO2 colloidal photocatalysts prepared by different methods [6–8]. As seen from Fig. 2, iron-dopant concentrations of up to 0.5 atom% increase ϕHCHO dramatically. It is generally accepted that Fe(III) centers form shallow charge trapping sites within the TiO2 matrix as well as on the particle surface through the replacement of Ti(IV) by Fe(III) [12]. Based on their favorable energy levels, Fe(III) centers may act either as electron or as hole traps leading to a temporarily more efficient separation of the photogenerated charge carriers. Thermal activation or tunneling can make these trapped charge carriers reavailable for interfacial charge transfer.

Quantum yields of HCHO formation in the presence of neat TiO2 and Fe(III)-doped TiO2 prepared by different methods. Method 1: referring Fig. 1a, where inorganic precursors FeCl3 and TiCl4 were used. Method 2: like method 1 (Fig. 1a), but organic precursors FeIII-acetylacetonate and Ti(O-i-C3H7)4 were employed. Method 3: using organic precursors FeIII-acetylacetonate and Ti(O-i-C3H7)4, but they were introduced into the reaction system at the same time (Fig. 1b) (adapted from Ref. [9]).

From Fig. 2, it is also seen that ϕHCHO is strongly affected by the method of photocatalyst preparation with the novel preparation, Fig. 1b, being superior to that of Fig. 1a for the optimum dopant concentration of 0.5 atom% iron, where ϕHCHO exhibits a ca. sixfold increase over the quantum yield measured in the presence of undoped TiO2 particles. The optimum iron-dopant concentration depends on the method of catalyst preparation (0.5 atom% for the preparations from organic precursors, 0.25 atom% for the preparation from TiCl4).

All Fe(III)-doped photocatalyst samples are comparable in particle size and have the same crystal structure. The difference in photocatalytic activity is thus only controlled by the Fe(III) content and the method of preparation. Sample preparation by hydrolysis of a homogeneous mixture of organic titanium and iron precursors in isopropyl alcohol (Fig. 1b) presumably proceeds under optimal conditions resulting in a uniform distribution of the dopant ions among the growing particles. Uniformity of doping at a given level is expected to result in enhanced photocatalytic activity. This was indeed verified by the determination of the quantum yield of formaldehyde produced by the photocatalytic oxidation of methanol in oxygen-saturated aqueous solution in the presence of TiO2 nanoparticles doped with Fe(III) by different methods (Fig. 1).

2.3 The antenna mechanism

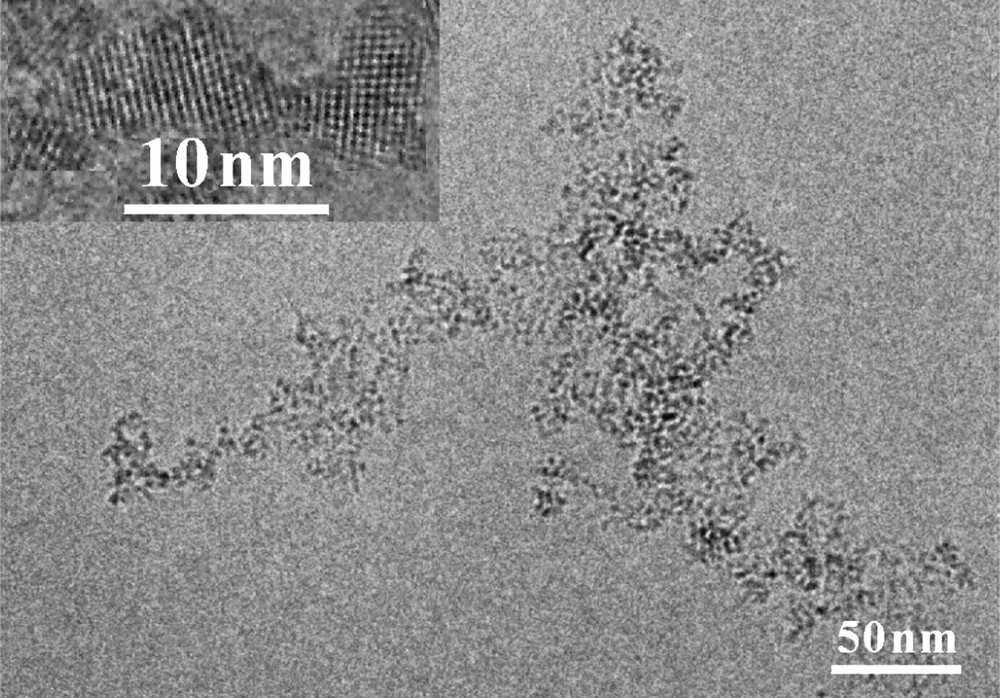

Fe(III)-doping via the novel method shows its superiority in photocatalytic oxidation of methanol. For a better understanding of this effect, the photocatalysts have been characterized by cryo-TEM and high resolution TEM (HRTEM) (Fig. 3) [9,10]. From Fig. 3, three features are observed for the Fe(III)-doped TiO2: (1) the particle sizes fall in the range of 2–4 nm; (2) the particles possess the crystal modification of anatase; and (3) the particles tend to form three-dimensional networks along a given crystallographic orientation.

Cryo-TEM and HRTEM (inset) of 0.5 at% Fe(III)-doped TiO2 prepared by novel method (adopted from Ref. [9]).

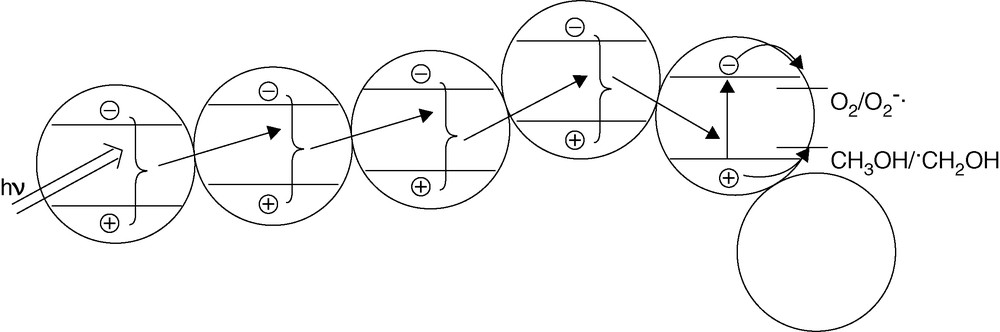

Cryo-TEM is a combination of cryo techniques with TEM, which allows to observe the nanoparticles in their native environment [9,10]. The observation by cryo-TEM indicates that three-dimensional TiO2 networks indeed exist in aqueous suspensions (Fig. 3). Based on this observation, we propose a novel mechanism that is shown in Fig. 4, i.e. the so-called antenna mechanism. Even if the target molecule is adsorbed on a photocatalyst particle at a certain distance from the light-absorbing particle, the latter can transfer the energy from particle to particle provided these particles are aggregated and possess the same crystallographic orientation. Once the energy has reached the particle with the adsorbed target molecule like methanol, the latter will act as a hole trap thus inducing the separation of the original exciton. Thus, a long chain of TiO2 particles aligned as shown in Fig. 4 will act as an antenna system transferring the photon energy from the location of light absorption to the location of reaction.

Antenna effect by network structure leading to enhanced photocatalytic activity.

It is envisioned that this antenna effect plays a significant role in all types of photocatalytic systems. Most currently used and commercially available photocatalyst powders, for example, consist of nanocristalline primary particles that are aggregated to form secondary structures with dimensions in the micrometer range. A material with a strong electronic coupling between the primary nanoparticles should hence exhibit a more pronounced antenna effect and thus a higher photocatalytic activity. Similarly, such an effect will also be operative in nanocrystalline transparent photocatalytic coatings where the target pollutant molecule or microorganism will not necessarily need to be located at the very location of the photon absorption.

Consequently, it should be possible to apply smart molecular engineering approaches to design photocatalytic systems exhibiting considerably higher activity than existing systems through an improvement of the electronic coupling between the semiconducting nanoparticles. This could lead to an important breakthrough in photocatalytic research since the photonic efficiency still represents the greatest bottleneck on the way from interesting laboratory results to a successful commercialization of most photocatalytic systems.

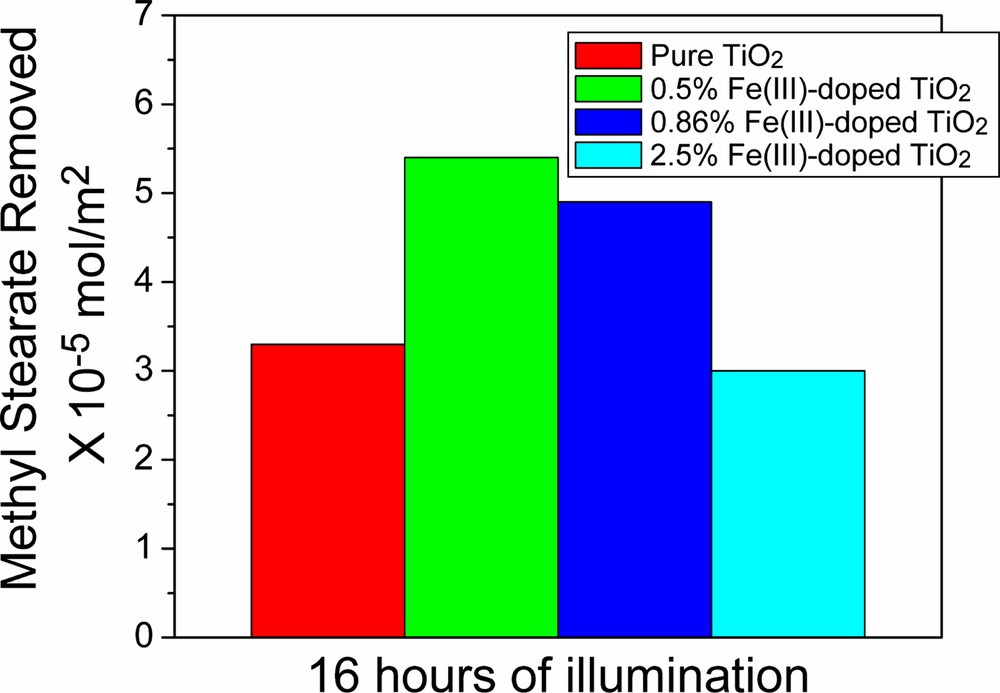

2.4 Applications

As characterized by TEM and HRTEM, the newly prepared Fe(III)-doped TiO2 nanoparticles are uniform in size, and tend to form three-dimensional networks. Such structured materials are advantageous in the formation of homogeneous and stable catalyst films and coatings that are urgently needed for many important applications of photocatalysis. For example, the materials can be used for the preparation of self-cleaning surfaces. The applicability in self-cleaning is demonstrated by the photocatalytic removal of methyl stearate (stearic acid methyl ester), as is shown in Fig. 5.

Testing the photocatalytic activity: rates of methyl stearate removal.

3 Platinized TiO2 colloids

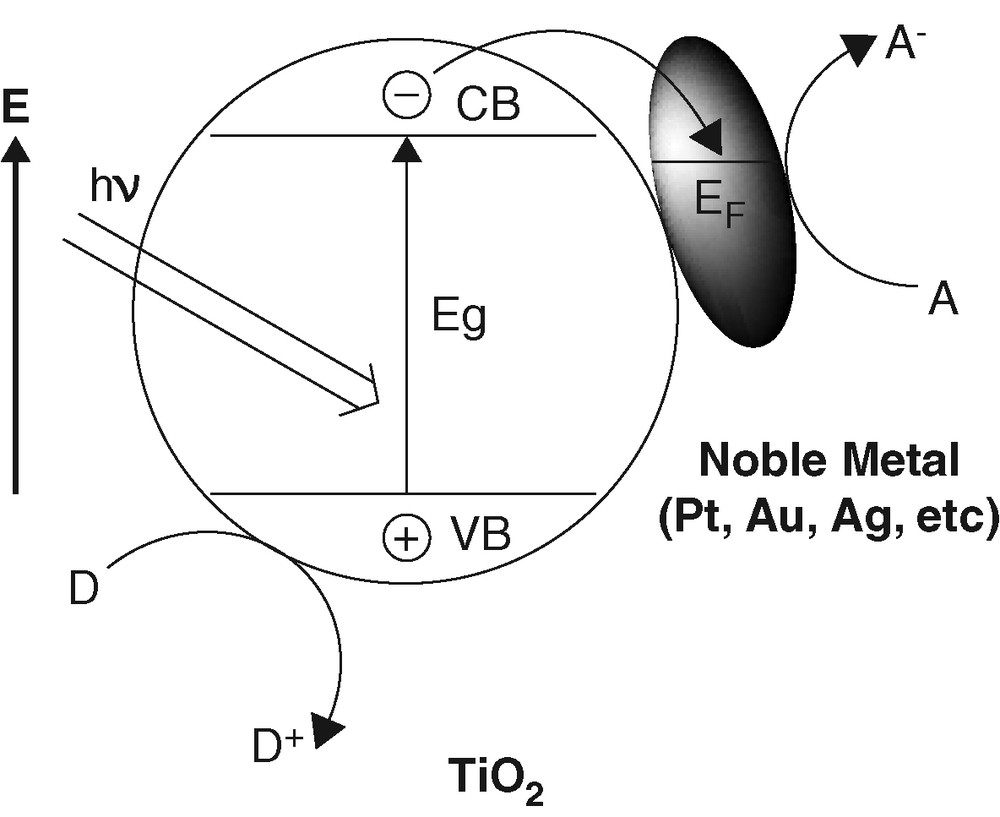

The presence of platinum as an electron sink (Fig. 6) has long been known to enhance the separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [20] and, hence, to improve the photocatalytic efficiency in general [21–23]. However, most of the previous studies were focused on the influence of the extent of platinization on the photocatalytic efficiency.

Promotion effect by noble metals on TiO2 photocatalysis.

Our focus in this area has been to highlight the influence on the photoefficiency of TiO2 by the intentional generation of network structures. Therefore, platinized TiO2 samples were prepared by two methods: (1) photochemical platinization of colloidal TiO2 (PtTi-S1); and (2) mixing of colloidal Pt and TiO2 (PtTi-S2).

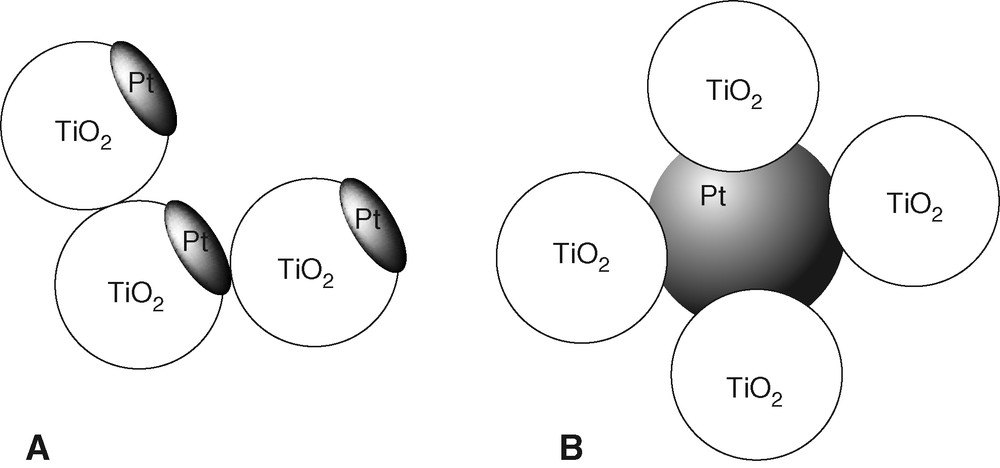

The shape of the Pt component in PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2 are expected to be different according to the preparation method, and so is the extent of interaction between Pt and TiO2. This apparently results in different promotion effects. Photodeposition of metals on TiO2 has been studied extensively. Wang et al. investigated the deposition of Au from AuCl4– on illuminated TiO2 by means of TEM, HRTEM and XPS [24,25]. Well-defined Au clusters formed on the particle surface by the growth of Au nuclei were identified. Similarly, the analogous preparation of PtTi-S1 by photodeposition of Pt from PtCl62– should yield Pt clusters on the TiO2 surface. In PtTi-S2 prepared by mixing of colloidal Pt with excess colloidal TiO2, the Pt particles should rather be surrounded by TiO2 particles. A corresponding proposal for the structure of the Pt promotion centers in the two photocatalysts is given in Fig. 7.

Models of PtTi-S1 formed by photodeposition of Pt (a) and of PtTi-S2 formed by mixing of colloidal Pt and TiO2 (b).

The in situ growth of Pt clusters during photodeposition leaves little doubt that the electronic interaction between Pt and TiO2 in PtTi-S1 is stronger than in PtTi-S2. Thus, PtTi-S1 is expected to exhibit a stronger promotion effect than PtTi-S2 under some specific conditions. This has been verified by the CW photolysis in the presence of O2 and repetitive laser-pulse photolysis in the absence of O2.

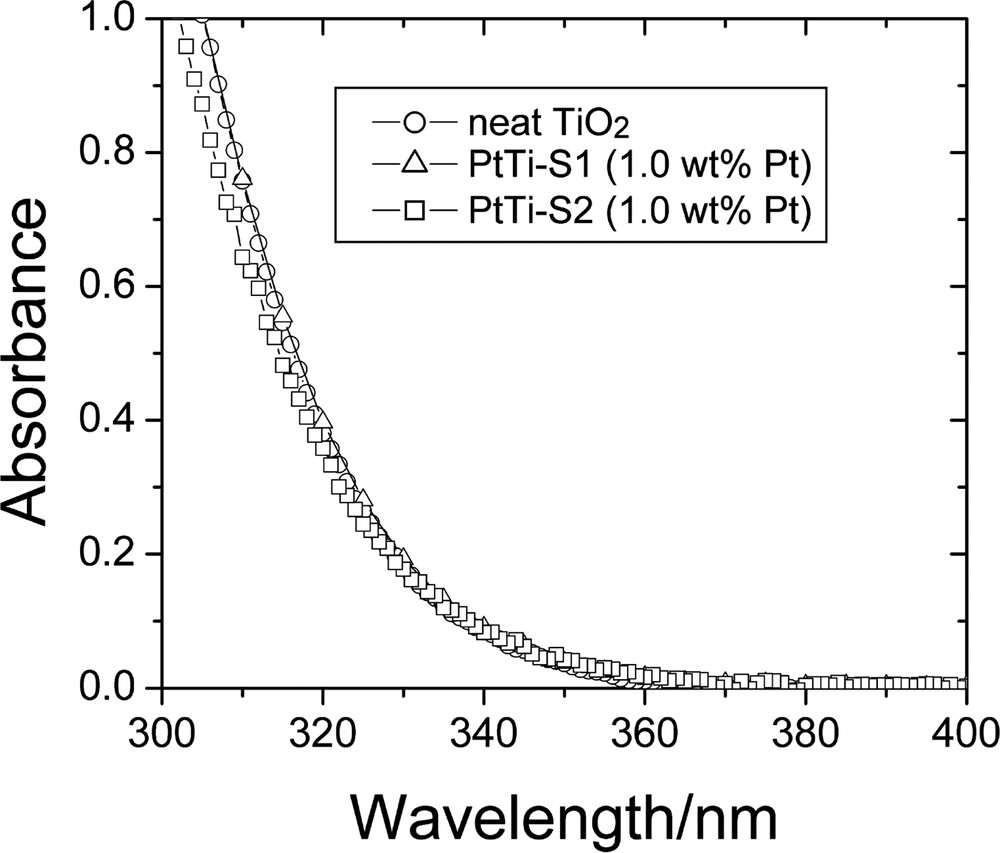

3.1 Optical absorption and network structure

Fig. 8 shows the absorption spectra of neat colloidal TiO2 and of the platinized TiO2 samples, PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2, respectively, in aqueous suspensions [11]. The optical absorption of TiO2 appears only in the UV region, where the absorbance increases steeply below 360 nm as it is characteristic of TiO2. There is virtually no light scattering at longer wavelengths. Comparison of the spectra shown in Fig. 8 evinces that the optical absorption of colloidal TiO2 hardly changes when the particles are modified either by deposition of traces of platinum (PtTi-S1) or by mixing with colloidal platinum (PtTi-S2). By use of the procedure proposed by Kormann et al. [26], the bandgap energy, Eg, of the colloidal TiO2 sample can be derived from the data shown in Fig. 8 as 3.35 eV, corresponding to an absorption onset at 370 nm. In comparison with bulk anatase TiO2 (Eg = 3.23 eV [27]), the bandgap of the neat colloidal TiO2 particles (3.35 eV) is increased by 0.12 eV.

Absorption spectra of as-prepared photocatalysts in aqueous suspensions (pH 3.5) at room temperature (0.1 g l−1 loading, 1 cm optical length) (adopted from Ref. [11]).

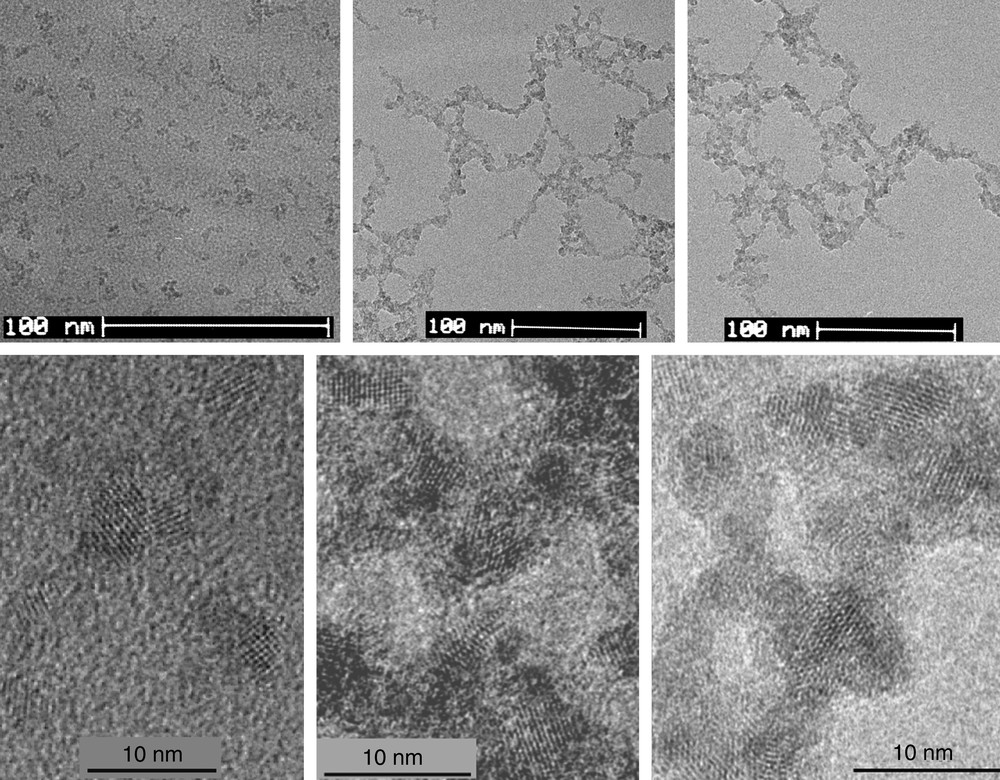

Fig. 9 shows TEM and HRTEM images of the thee photocatalysts. As shown in Fig. 9, neat colloidal TiO2 (average particle diameter ca. 2.4 nm, see also Ref. [26]) tends to form comparatively small aggregates with no distinct orientation. The Pt@TiO2 samples (PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2) clearly exhibit large networks of interconnected chains or branches of aggregated particles.

TEM (up) and HRTEM (down) images of the photocatalysts: neat TiO2, PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2 with 1 wt.% Pt (from left to right) (adopted from Ref. [11]).

In the HRTEM images (Fig. 9) crystal planes of the particles compatible with the anatase modification of TiO2 can be recognized [11]. This was further confirmed by electron diffractograms and evaluations of the Fourier transforms of the HRTEM images (see also Refs. [9,10]). No crystal structure corresponding to platinum was observed. This is understandable when considering the very small content of only 1 wt.% Pt. However, the promotion centers should be embedded in the chain-like structures of the particle aggregates seen in the TEM images of PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2 (Fig. 9). As estimated from Fig. 9, the size of the PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2 particles falls in the range 1.5–4 nm, comparable to that of neat TiO2 particles that have an average diameter of ca. 2.4 nm.

The photocatalytic performance of the three photocatalysts including neat TiO2, PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2, was investigated by measuring the quantum yield, ϕHCHO, of HCHO formed from aqueous methanol at pH 3.5 under different conditions. The improvement of ϕHCHO by platinization was found both in continuous (CW) UV-photolysis and after repetitive 351-nm laser-pulse photolysis.

3.2 CW vs. laser photolysis

Upon exposure of O2-saturated aqueous suspensions, containing one of the photocatalysts and methanol, to 300–400 nm CW light, HCHO was produced and identified quantitatively by HPLC analysis. Other products were not detected by HPLC. HCHO was not formed in the dark or during photolysis in the absence of the TiO2-based samples, evincing that the process is truly photocatalytic [11].

Fig. 10a demonstrates that the concentration of HCHO in the presence of the photocatalysts increases linearly with illumination time [11]. Hence, the photochemical reaction rate is given by the slope of the straight lines shown in Fig. 10a. Thus, the quantum yields, ϕHCHO, in the presence of the various photocatalysts are readily obtainable. The result is shown in Fig. 10b for neat colloidal TiO2 and the Pt@TiO2 catalysts at an increasing loading by platinum. Obviously, platinization has a strong promoting effect on the formation of HCHO in TiO2-based photocatalysis. ϕHCHO increases by up to 50–70% when compared with that value on neat TiO2 particles. From Fig. 10, it is also obvious that photochemical platinization of the TiO2 particles yields a more efficient photocatalyst (PtTi-S1) than mixing of the colloidal components of Pt and TiO2 (PtTi-S2). This is attributed to the structural difference between PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2 including the dispersity of Pt on TiO2, and the electronic interaction between Pt and TiO2 (cf. Fig. 7).

Production of HCHO in the presence of colloidal photocatalysts TiO2, PtTi-S1 and PtTi-S2 as a function of illumination time during CW photolysis (a) and relevant quantum yields (b). Catalyst loading, 100 mg l–1; 30 mM aqueous CH3OH (O2-Sat’d, pH 3.5); reaction volume, 50 ml; I0 = 3.37 × 10–6 Einstein l–1 s–1 (ca. 300–400 nm) (adopted from Ref. [11]).

Photocatalytic oxidation of aqueous methanol was also studied by applying repetitive 351-nm laser-pulse photolysis both in the presence and absence of oxygen as an electron acceptor [11]. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 11.

Setup for repetitive 351-nm laser-pulse photolysis.

In the oxygenated sample solutions, the quantum yields of HCHO formation were measured after 0.5-Hz illumination by 200 laser-pulses (10–20 ns pulse width). As seen from Table 1, in the presence of neat colloidal TiO2, ϕHCHO was 0.032 ± 0.002, ca. 50% larger than for CW photolysis. Likewise, ϕHCHO was increased by a factor of ca. 1.5 when the laser-pulse photolysis was applied on suspensions containing the platinized photocatalysts (1 wt.% Pt), regardless of their preparations. Most importantly, it was found that repetitive laser-pulse photolysis improved ϕHCHO (Table 1) substantially and by the same factor (ca. 1.5) over CW photocatalysis (Fig. 10) for all the photocatalysts studied although in both modes of photolysis the time-averaged molar photon absorption rate was approximately the same (ca. 8 × 10–7 Einstein l–1 s–1) [11]. A rationalization of these findings will be presented in Section 3.4.

Quantum yields, ϕHCHOa, of formaldehyde formation from aqueous methanol at various nanocrystalline TiO2-based photocatalysts under different conditions (adopted from Ref. [11])

| Photocatalyst |

|

|

|

| 2.4 nm TiO2 | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 0.032 ± 0.002 | 0.027 ± 0.002 |

| 0.034 ± 0.003 | 0.047 ± 0.002 | 0.049 ± 0.002 |

| 0.031 ± 0.002 | 0.048 ± 0.002 | 0.033 ± 0.002 |

a Catalyst loading 0.1 g l–1, pH 3.5 and room temperature throughout.

b Ia = 8 × 10–7 Einstein l–1 s–1, 30 mM methanol, Fig. 6.

c Train of 200 pulses (10–20 ns), repetition frequency 0.5 Hz, ca. 6 × 10–9 Einstein/pulse (ca. 0.35 e–/h+-pairs per particle per pulse), <Ia> ≅ 7–10 × 10–7 Einstein l–1 s–1 (time average), 30 mM methanol.

d Train of 600–690 pulses (10–20 ns, 0.5 Hz), ca. 5 × 10–9 Einstein/pulse (ca. 0.3 e–/h+-pairs per particle per pulse), <Ia> ≅ 6–8 × 10–7 Einstein l–1 s–1 (time average), 250 mM methanol.

3.3 O2-saturated vs. N2-saturated

Apart from photocatalysis under oxygenated condition, the quantum yields of HCHO formation in the de-oxygenated sample solutions by laser-pulsed photolysis were also measured. As seen from Table 1, HCHO was produced with similar quantum yields compared with those measured in the presence of oxygen. This indicates that a (photo)electron acceptor other than O2 is operative. However, a closer inspection of ϕHCHO in Table 1 shows that neat TiO2 and PtTi-S2 are less efficient photocatalysts for methanol oxidation in O2-free than in O2-saturated suspension while the activity of PtTi-S1 remains virtually unchanged.

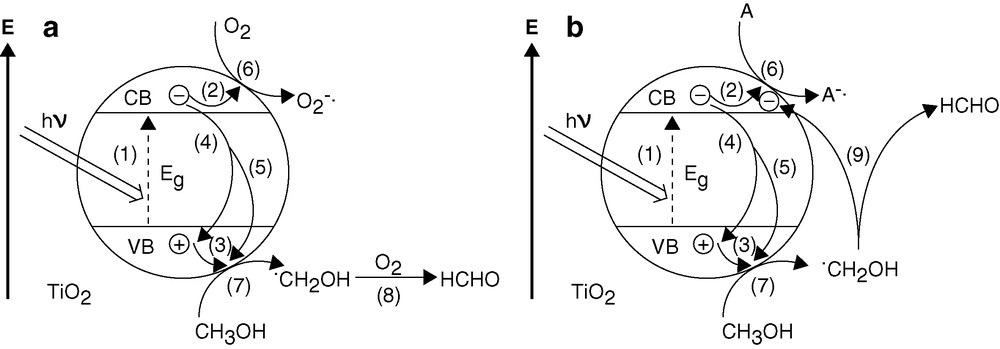

In general, the presence of O2 is considered as a prerequisite for efficient TiO2-photocatalyzed oxidation of organic pollutants in wet systems [28]. Similarly, the gas-phase photocatalytic oxidation of 2-propanol to produce acetone and water on single-crystalline TiO2 proceeds only in the presence of co-adsorbed O2 [29]. Contrary to expectation, removal of O2 by purging the suspensions with N2 resulted in only a small decrease of ϕHCHO (ca. 15%) for neat TiO2 and no change for PtTi-S1. A somewhat larger decrease of ϕHCHO (ca. 30%) was observed for PtTi-S2, see Table 1 (laser-pulse photolysis). Although O2 may not have been removed completely by purging with N2, the result suggests that in (nearly) oxygen-free suspensions a species A other than O2 acts as photoelectron acceptor, and the •CH2OH intermediate is converted to HCHO via a different route. This is illustrated in Fig. 12.

Mechanism of TiO2-photocatalyzed HCHO in the presence of O2 saturation (a) and via current-doubling (b) in the presence of e–-acceptor A (H+ and/or residual O2) in N2 purged suspension. (1) Photogeneration of the charge carriers e– and h+; (2) and (3) surface trapping of the charge carriers; (4) and (5) recombination channels; (6) e–-transfer to the acceptor: formation of O2–•/HO2• (a) or A– (b); (7) first oxidation step of CH3OH; (8) formation of HCHO by e–-transfer from •CH2OH to O2; (9) formation of HCHO by e–-injection from •CH2OH into the conduction band of TiO2 (current-doubling).

A potential e–-acceptor in the absence of molecular oxygen is the hydrogen ion ( and/or in Fig. 12b) present in the suspensions at pH 3.5. Reduction of H+ to give H2,

| (8) |

Dispersed Pt formed as a cluster on the TiO2 particles in PtTi-S1 (Fig. 7a) should strongly catalyze the H2 formation, while the compact Pt particles in PtTi-S2 (Fig. 7b) should be the poorer electrocatalysts for H2 evolution. From these considerations and the assumption that the reduction of H+ is rate-controlling for the formation of HCHO in O2-free suspension, it can be understood why ϕHCHO on PtTi-S1 is found to be larger than on PtTi-S2, see the last row in Table 1.

3.4 The deaggregation concept

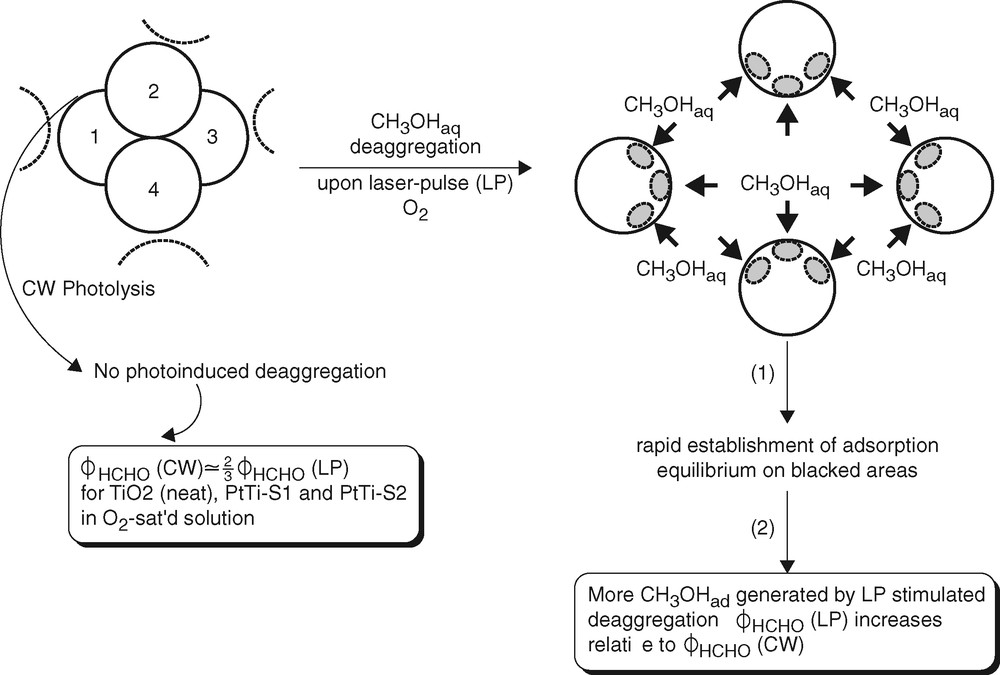

Regardless of the photocatalyst employed, repetitive laser-pulse illumination increased ϕHCHO in the oxygenated suspensions by a factor of ca. 1.5 in comparison with CW illumination, although in both modes of photolysis the time-averaged photon absorption rate was approximately the same (Table 1). Previous studies on intermittent illumination in TiO2 photocatalysis [33–38] offer no explanation for this observation.

Cornu et al. investigated the quantum yield, ϕF, of photocatalytic formate oxidation in oxygenated acidic TiO2 suspension under continuous and periodic pulse illumination [38]. For very short illumination times in periodic pulse photolysis, Cornu et al. demonstrated that ϕF was identical to the value obtained under continuous illumination at the same time-averaged photon absorption rate. This is in sharp contrast to our results for photocatalytic methanol oxidation (Table 1).

As a tentative explanation of the increase of ϕHCHO obtained by repetitive laser-pulse illumination, we propose laser-pulse-stimulated deaggregation of the TiO2 particle agglomerates shown in the TEM images (Fig. 9) [11]. Such a process would increase the surface area available for reactant adsorption at a given photocatalyst loading and would thus lead to an increase of the photocatalytic reaction rate, and of ϕHCHO, upon applying a large number of laser pulses at a given average photon absorption rate. For a rough estimate of the gain in photocatalyst surface by deaggregation we assume that 1/12 of the single-particle surface is shielded from adsorption by the presence of one adjacent particle. (A spherical particle inside a close-packed structure of identical spheres is surrounded by 12 nearest neighbors and would not contribute to adsorption.) From the comparison of four single particles, 4A, in Fig. 13 with the unshielded surface of the tetramer, 4A-(12/12)A, the catalyst surface available for adsorption increases by a factor of 1.33 upon deaggregation. The factor increases with the number of particles in a close-packed aggregate.

Model of laser-pulse-induced deaggregation.

The energetic requirement for deaggregation is met. The average number of photons absorbed per TiO2 particle per laser pulse is 0.3 (Table 1). The average photon energy deposited in the particle (Fig. 13) is therefore at least 341 kJ mol–1 per laser pulse at 351 nm. The inter-particle bond energy is only ca. 30 kJ mol–1 [39]. The photocatalytic formation of HCHO from CH3OH + O2 is exothermal. The energy supplied by the first few of the 200 pulses applied for photolysis (Table 1) would therefore be sufficient for the supposedly stepwise deaggregation of even larger agglomerates than the tetramer. Reaggregation of the particles is a slow process. This is concluded from the temporal evolution of small UV-spectral changes observed after suspending the neat TiO2 colloid and from a kinetic study [40] of reversible agglomeration of TiO2 nanocolloids. Diffusion of reactants is not rate-controlling under the conditions of this and related studies of photocatalytic processes [38].

In CW photolysis the absorption of a photon is a rare event compared with the high-intensity illumination by the laser pulse. The aggregation remains intact under CW illumination because there is enough time for redistribution of the photon energy among the many vibrational modes before the same aggregate absorbs a second photon.

4 Summary

Two types of modified TiO2 photocatalysts, i.e. Fe(III)-doped and platinized TiO2, are addressed in this review. The effect on the TiO2 photoactivity by Fe(III)-doping and platinization has been evaluated by comparing the quantum yield of HCHO formation under different conditions including CW and laser photolysis, oxygenated and/or deoxygenated. Based on the detailed analysis of our experimental observations, the following conclusions have been drawn:

- • the distribution of Fe(III) and Pt within the TiO2 matrix and/or on the surface plays a vital role in promoting TiO2 photoactivity. On the one hand, a novel synthetic route (Fig. 1b) provides optimal conditions for uniform doping and growth of particles yielding a highly active photocatalyst for the oxidation of methanol in oxygenated aqueous solution. On the other hand, PtTi-S1, platinized TiO2 by photodeposition, exhibits higher activity than PtTi-S2, prepared by physically mixing colloidal TiO2 with Pt nanoparticles. The in situ growth of Pt clusters during photodeposition generates Pt in a better dispersion than in PtTi-S2;

- • cryo-TEM of vitrified samples confirms earlier assumptions that TiO2 nanoparticles tend to form three-dimensional networks in solution. A novel energy transfer mechanism is suggested employing these three-dimensional networks as antenna systems leading to improved photocatalytic activities of the colloidal preparations. The antenna mechanism is well supported by the platinization effect. An extended network structure is also observed in platinized TiO2 photocatalysts. On the one hand, a very small extent of platinization in PtTi-S2 (particle ratio of Pt/TiO2 is ~1:1000) promotes the photocatalytic oxidation of methanol substantially, where ϕHCHO is increased by a factor of ~1.5. Platinum as an electron sink on the TiO2 particles improves their photoactivity in general. On the other hand, Pt apparently favors particle aggregation to form the chain-structures which are prerequisites for the fast transport of excitation energy or of photogenerated charge carriers as postulated above. We believe that platinization, at least in the present case, has this dual function leading to the observed enhancement of ϕHCHO;

- • under repetitive laser-pulse illumination ϕHCHO is increased by ca. 50% for all the photocatalysts in comparison with CW illumination at the same average photon absorption rate. To explain this unexpected observation, the so-called deaggregation concept has been developed. By laser-pulse-stimulated deaggregation of colloidal TiO2 and by fragmentation of the networks in case of the platinized samples the photocatalyst surface is increased, and thus its photoactivity is improved.

All our experimental observations suggest that structural properties of the photocatalysts such as distribution of Fe(III) ions in the TiO2 matrix and/or on the surface, aggregation/deaggregation and Pt-assisted network formation as well as the dispersity of Pt are important factors for the photocatalytic activity of these materials. Further studies concerning the response of the structural features to the illumination parameters are definitely indicated.

Acknowledgments

Chuan-yi Wang thanks the Alexander von Humboldt (AvH) foundation for a research fellowship grant. The authors thank Dr. Christoph Böttcher, Freie Universität Berlin, Forschungszentrum für Elektronenmikroskopie, for taking the electron micrographs. The authors also thank Mr. Thomas Kolrep, Freie Universität Berlin, Institut für Chemie, for his assistance in HPLC measurements. Financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants BA 1137/3-1, BA 1137/4-1 and DO 150/7-1) is gratefully acknowledged.