1 Introduction

Generally, in catalysis the catalyst is considered as a finely designed material exhibiting intrinsic properties being directly influenced by the chemical composition and the synergy between its components. A new catalyst formulation should therefore go through complete understanding of its single components, their interactions and properties.

Over the last decades, ionic liquids (ILs) have become a prominent class of compounds in liquid-phase chemistry. Their excellent physicochemical properties, like good thermal stability and electric conductivity, reasonable viscosity, large liquid-phase state existence and low vapor pressure render these materials promising in the frame of sustainable chemistry [1]. ILs are ionic liquid salts similar to molten salts, with the only difference lying in their melting points, usually inferior to 100 °C. Their physical and chemical properties can be easily tuned by varying the cation, usually organic, and the anion, usually inorganic [2,3]. Although the properties of ILs as solvents are well demonstrated, their use in catalysis remains barely explored. Moreover, their immobilization on a support presents an interesting opportunity for fundamental catalytic studies. In addition, the use of supported catalysts presents the advantages of separation ease in liquid-phase processes or a direct use in gas–solid reactions. The higher viscosity of ILs compared with classical solvents facilitates the formation of a thin IL layer surface where the diffusion becomes considerably faster.

IL materials can be, for instance, grafted on functionalized carbon nanofibers (CNF) or encapsulated in a zeolite matrix [4–6]. Bearing in mind that IL-functionalized zeolites or supported ILs could be designed to possess an acid function given either by the zeolite matrix or by the IL itself; the development of this kind of material raises scientific interest, especially in the field of acid catalysis. An additional beneficial feature for these materials relies on the direct combination of both acid and solvent functions, which could further improve the selectivity toward the desired products and warrant their separation.

Chloroaromatic compounds are useful intermediates in the pharmaceutical industry and for the synthesis of pesticides. However, the classical methods for their production usually lead to a mixture of products difficult to separate. Considerable efforts have therefore been undertaken to achieve higher selectivity either by changing the solvent or the catalyst, acidity and solvent properties being key parameters. Recently, important advances were made by applying an environmentally friendly method for aromatics halogenation using trichloroisocyanuric acid (TCCA, C3N3O3Cl3) as chlorination agent [7–11].

The aim of the present study was to investigate the possible use of IL-modified materials, more precisely IL-grafted carbon nanofibers and IL encapsulated in zeolites, as valuable catalysts for toluene chlorination. The catalysts were rationally designed to evaluate only the ionic liquid function in catalysis. It is also worth mentioning that detailed characterization of both materials, IL/CNF and IL/zeolites, is not the subject of this contribution.

2 Experimental

2.1 IL-functionalized CNF preparation

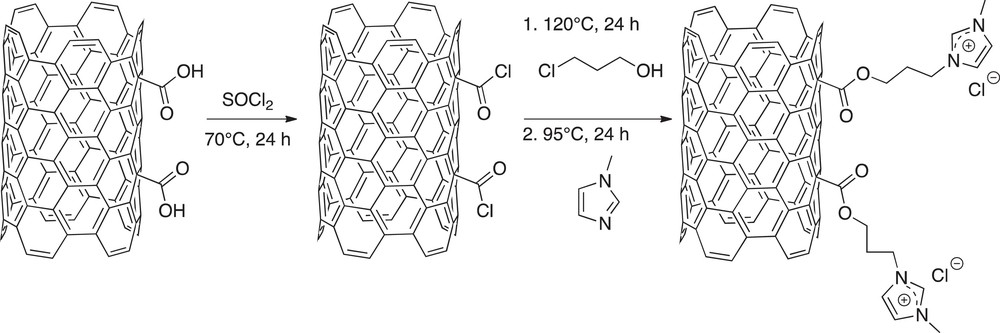

Several strategies have been described in the literature for anchoring ILs on a solid surface [12–14] via functionalization of a support and subsequent ILs grafting. The same strategy was conducted in our work, starting with an oxidative treatment of CNF [15]. The aim of this pretreatment was to enhance the number of O-containing functional groups on the CNF surface; the presence of numerous carboxylic groups is especially targeted. Commercially available CNF (GANF13, Grupo Antolin Ingeniería) were mixed with nitric acid (69%) at 60 °C under a 24-h ultrasonic treatment. After washing and filtration, oxidized CNFs were submitted to a reaction with SOCl2 in the absence of air at 70 °C during 24 h. The excess of thionyl-chloride was removed by washing with anhydrous THF, the latter being itself removed by evaporation. The next step of the immobilization process consisted of reacting treated CNF with 3-chloro-1-propanol at 120 °C for 24 h under reflux in the absence of air. Unreacted 3-chloro-1-propanol was removed by washing with CH2Cl2. Finally, the reaction was conducted with 1-methyl imidazole under reflux at 95 °C during 24 h to allow the formation of immobilized IL 1-butyl 3-metyl imidazolium chloride–[bmimCl]. All reaction steps during the grafting procedure are summarized in Scheme 1.

Ionic liquid immobilization steps on CNF.

Once immobilized IL is obtained, AlCl3 was added by incipient wetness impregnation to the composite (in adequate amount) to finally form [bmimAlCl4] and [bmimAl2Cl7] catalysts supported on CNF.

2.2 IL encapsulation in zeolites

Two IL/zeolite samples and their corresponding pristine zeolites were prepared as described elsewhere [4,5]. The synthesis of ZSM-5/IL composite was performed as follows: 4.1 g of 1-butyl-3-methyl imidazolium methanesulfonate [bmimCH3SO3], 1.22 g of NaOH and 0.29 g of NaAlO2 were dissolved in 66 mL of distilled water and heated at 35 °C. Once the temperature was reached, 28.9 g of TEOS were added and the solution was further aged for 4 h. Then, a hydrothermal synthesis was performed in a stainless steel autoclave at 180 °C during five days. The solid obtained was filtered, thoroughly washed with ethanol and dried at room temperature. The same synthesis was followed for BEA/IL composite, the only difference being the nature of silica source used: colloidal silica (Aerosil) in place of TEOS.

All the zeolites were tested in the reaction as prepared (no cationic exchange was carried out) in order to investigate the sole role of ILs as a potential catalyst.

2.3 Catalytic reaction

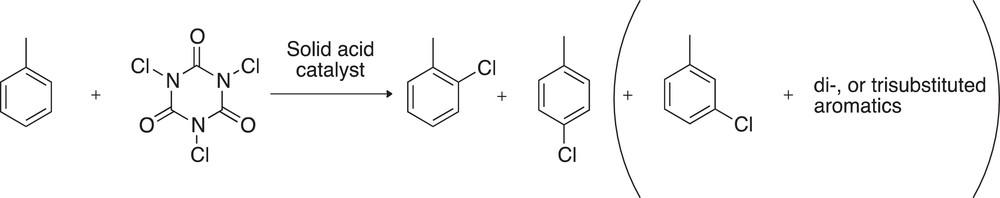

The reaction was carried out in 5 mL of dichloroethane; toluene (1 mmol, 0.106 mL, 1 eq.), TCCA (0.34 mmol, 0.079 g, 0.34 equiv) and the respective heterogeneous catalysts (100 mg) were added. The solution was stirred at room temperature or 83 °C at 500 rpm velocity. The samples withdrawn for GC analysis were treated to neutralize residual TCCA. Namely, 0.5 mL of the reaction mixture were cooled down and vigorously stirred with 3 mL of a 10 %wt. Na2S2O3 solution. From the resulting biphasic solution, the organic layer was separated and dried over Na2SO4 and finally injected in the gas chromatograph (GC II 5890 Hewlett Packard) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID). In principle, the chlorination of alkyl benzenes leads to mono-, di- or tri-substituted aromatics. Para- and ortho-substituted aromatics are favored in the case of toluene (Scheme 2). The degree of toluene conversion and the respective selectivities toward chlorinated compounds were calculated after calibration with standards.

Expected reaction products obtained during toluene chlorination reaction.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 IL functionalized CNF

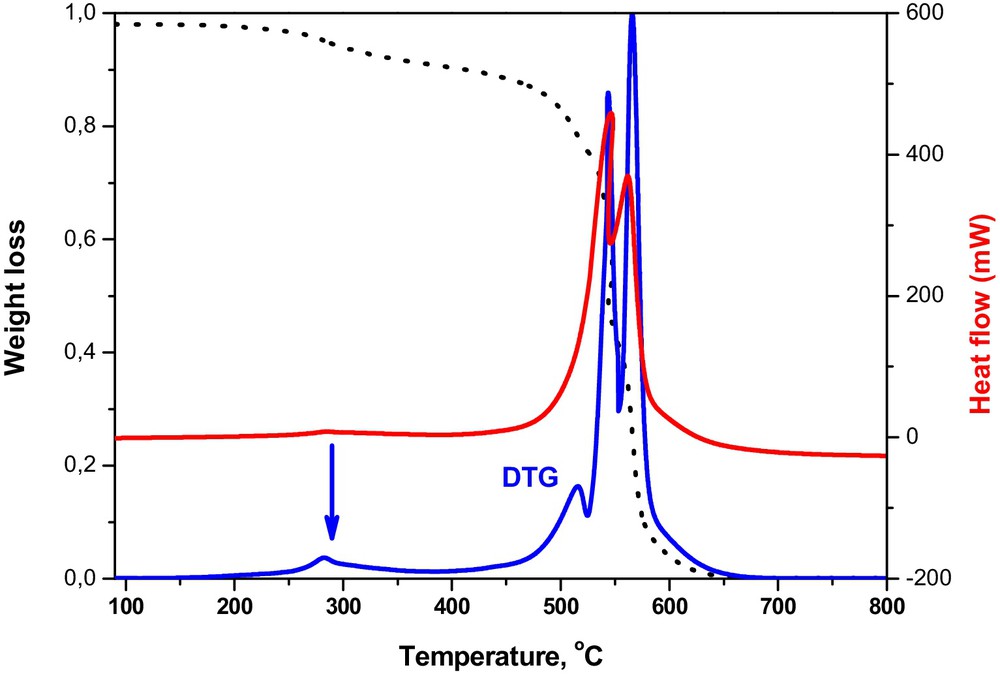

Although the full characterization of the samples was not the aim of the study, the amount of immobilized [bmimCl] was determined by thermo-gravimetric analysis (Fig. 1).

(Color online). Thermo-gravimetric analysis of IL functionalized CNF.

A three-step weight loss was observed. The loss of water occurred below 200 °C, followed by the oxidation of the ionic liquid between 300 and 420 °C and finally by the oxidation of CNF above 500 °C. The strong exothermicity of the latter two processes confirms that both are combustion reactions. An amount of 11 wt% of IL was calculated by this analysis as attached to the CNF support. Thus, 11 and 22% of AlCl3 were therefore added to IL-CNF composite to produce the [bmimAlCl4]-CNF and [bmimAl2Cl7]-CNF catalysts. The catalytic data are presented in Table 1.

Toluene conversion and selectivity toward chlorinated products for IL/CNF catalysts.

| Entry | Catalyst | Conversion (%) 24 h | Conversion (%) 96 h | Selectivity mono- (%) | Selectivity ortho- (%) | Selectivity para- (%) | Ortho/para ratio | Selectivity meta- (%) |

| 1 | [bmimAlCl4]-CNF | 3.2 | 88 | 35 | 53 | 0.66 | 12 | |

| 2 | [bmimAlCl4]-CNF | 5.4 | 100 | 36 | 46 | 0.78 | 18 | |

| 3 | [bmimAlCl4]-CNFa | 9.8 | – | 100 | 33 | 40 | 0.83 | 27 |

| 4 | [bmimAl2Cl7]-CNF | 3.8 | 100 | 31 | 43 | 0.72 | 26 | |

| 5 | [bmimAl2Cl7]-CNF | 7.2 | 100 | 34 | 38 | 0.89 | 28 | |

| 6 | [bmimAl2Cl7]−CNFa | 9.9 | – | 100 | 27 | 37 | 0.73 | 36 |

| 7 | AlCl3 | 12.3 | 100 | 45 | 50 | 0.90 | 5 | |

| 8 | CNF | 1.4 | 100 | 36 | 64 | 0.56 | 0.1 |

It is noteworthy that IL/CNF composites exhibit low degrees of toluene conversion at room temperature after 24-h reaction (entries 1,3,4 and 6). An increase to roughly 10% of toluene converted was achieved while raising the temperature from room temperature to 83 °C for [bmimAlCl4]/CNF and [bmimAl2Cl7]/CNF, respectively (entries 2 and 5). The catalytic activity was increased for [bmimAlCl4]/CNF and [bmimAl2Cl7]/CNF with time, suggesting possible hindered accessibility to the active sites. The [bmimAl2Cl7]/CNF composite appears more active than its AlCl4−anion counterpart. It seems, therefore, that the nature and availability of the anion has an important influence on the catalyst's performance. Among all IL/CNF catalysts, a nearly complete selectivity in mono-substituted chloroaromatics was observed.

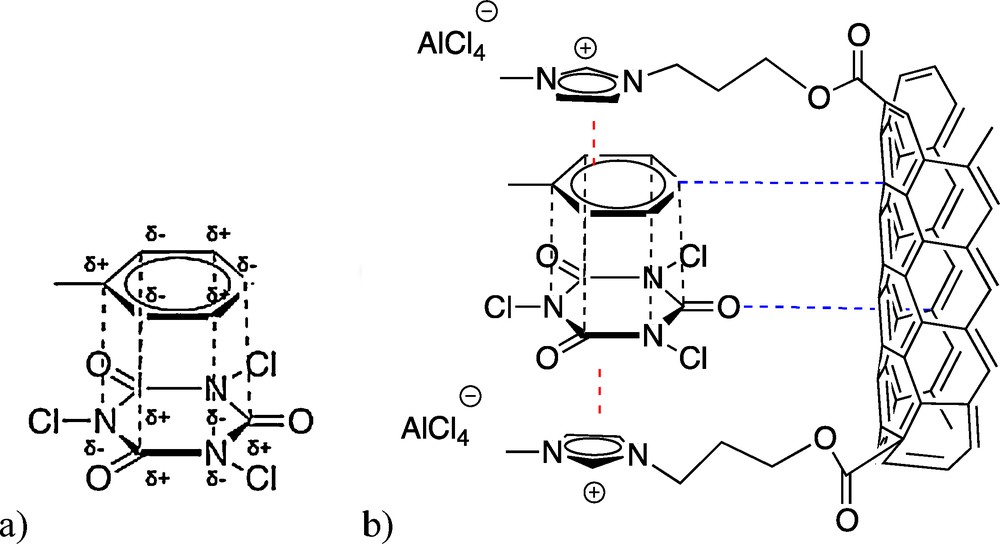

However, the main difference between ILs/CNF and AlCl3 lies on the selectivity toward the meta-chlorotoluene isomer. Surprisingly, non-favored electrophilic substitution occurred in meta position at high selectivities for IL/CNF materials. At nearly 10% of toluene conversion, 27 and 36% of meta isomer were detected after 24 h of reaction over [bmimAlCl4]/CNF and [bmimAl2Cl7]/CNF catalysts, respectively (entries 3 and 6). In addition, it seems that raising both reaction time and temperature led to an enhanced selectivity in meta-isomer with respect to the expected ortho/para isomers. Furthermore, this a priori unusual selectivity in the meta position seems to increase while raising IL composite loading (from 11 to 22 wt.%). In order to verify whether this effect is caused by the sole IL or the composite, equal amounts of AlCl3 and CNF were tested and the results are also shown in Table 1, entries 7 and 8. Apparently, neither AlCl3 nor CNF alone are responsible for such high meta-chlorotoluene selectivity. A polarized π-stacking effect could, at least partially, explain this unconventional catalytic behavior. Indeed, a polarized π-stacking accounts for a strong polarization of the aromatic-like rings through van der Waals (Keesom) forces induced by the presence of the substituents [16–19]. Regarding our system, TCCA is a pre-conjugated 6-membered ring and imidazole has the possibility to participate in a normal π-stacking. One may expect possible interactions between the catalyst and the reactants as schematized in Fig. 2. Even though toluene and TCCA may act as polarized conjugated aromatic rings, nothing similar could be observed with conventional catalysts [8–10,20]. The presence of this complex in the vicinity of the catalyst may induce a steric hindrance avoiding para-chlorotoluene formation. Hence, its interaction with imidazole lowers this possibility in favor of an ortho orientation. Nevertheless, the IL/CNF composite could stabilize this transition state by acting like a π-stacking plier and thus enhance the formation of a relatively high amount of meta-chlorination product, the meta-position being in direct vicinity of the electrophilic chlorine atom.

Catalyst/Reactants interactions. (a) Possible polarized π-stacking. (b) Stabilization of this transition state by both orthogonal and parallel π-stacking.

3.2 IL encapsulation in zeolites

As described elsewhere [4,5], ionic liquids could be directly used in the zeolite synthesis as a template, thus resulting in the encapsulation of the IL in the zeolite framework without any change in its composition. The use of TEOS as a silicon source and [bmimCH3SO3] as a templating agent results in IL/Na-ZSM-5 composite with the IL remaining trapped within the zeolite structure. The latter IL adopts a configuration where the longer alkyl chain of substituted imidazolium enters the secondary cages of the structure. It was checked that under the same conditions but in absence of IL, a pure Na-ZSM-5 structure was obtained. The replacement of the silicon source by aerosil led to the formation of IL/BEA composite with IL playing the role of the charge compensation cation. In the absence of IL in the gel, the sole mordenite structure was obtained. Table 2 summarizes the catalytic data obtained with those zeolites and IL/zeolite composites (as-prepared composites were tested in their Na+-form).

Toluene conversion and selectivity toward chlorination products achieved over IL/zeolite composites.

| Entry | Catalyst | Conversion (%) 24 h | Selectivity mono- (%) | Selectivity para- (%) | Selectivity ortho- (%) | Ortho/para ratio | Selectivity meta- (%) |

| 1 | Na-ZSM5 | 3.4 | 98.5 | 60 | 37 | 0.62 | 1 |

| 2 | Na-ZSM5a | 29.8 | 100 | 60 | 35 | 0.58 | 5 |

| 3 | IL-Na-ZSM5 | 2.2 | 100 | 64 | 34 | 0.53 | 1 |

| 4 | IL-Na-ZSM5a | 17.4 | 100 | 58 | 35 | 0.60 | 6 |

| 5 | IL-NaBEA | 5.9 | 100 | 51 | 47 | 0.92 | 1 |

| 6 | IL-BEAa | 29.6 | 99.9 | 48 | 47 | 0.98 | 4 |

| 7 | Na-MOR | 2.7 | 98.4 | 60 | 34 | 0.57 | 5 |

| 8 | Na-MORa | 15.0 | 100 | 63 | 34 | 0.54 | 2 |

Likewise ILs/CNF catalysts, ILs/zeolites exhibited low toluene conversion at room temperature accompanied by the nearly selective formation of monochlorination products (entries 3–6). It is worthy to mention that the presence of IL further inhibits the reaction with respect to Na-zeolite, probably by hindering the accessibility to the active sites in the zeolite framework. This is further supported by a slight decrease in the ortho/para ratio for IL/ZSM-5 composite (entries 3 and 4) compared with pristine ZSM-5 (entries 1 and 2). In addition, a higher conversion was achieved over BEA and MOR composites containing larger pores (entries 5 and 6). In the latter two cases, the presence of IL induces an enhanced chlorination reaction performance (a two-fold rise in conversion was achieved over IL/BEA). Moreover, a higher quantity of ortho isomer was observed over IL/BEA composite, thus indicating the absence of steric hindrance in this zeolite. When the catalytic test was carried out at 83 °C (entry 4), a higher conversion was reached, as expected, along with nearly para/ortho ratio = 2, which is in line with former results obtained for acidic ZSM-5 zeolites by Mendonça et al. [8]. In contrast to IL/CNF system, almost no meta-isomer could be detected over IL/zeolite systems (selectivity being < 6%).

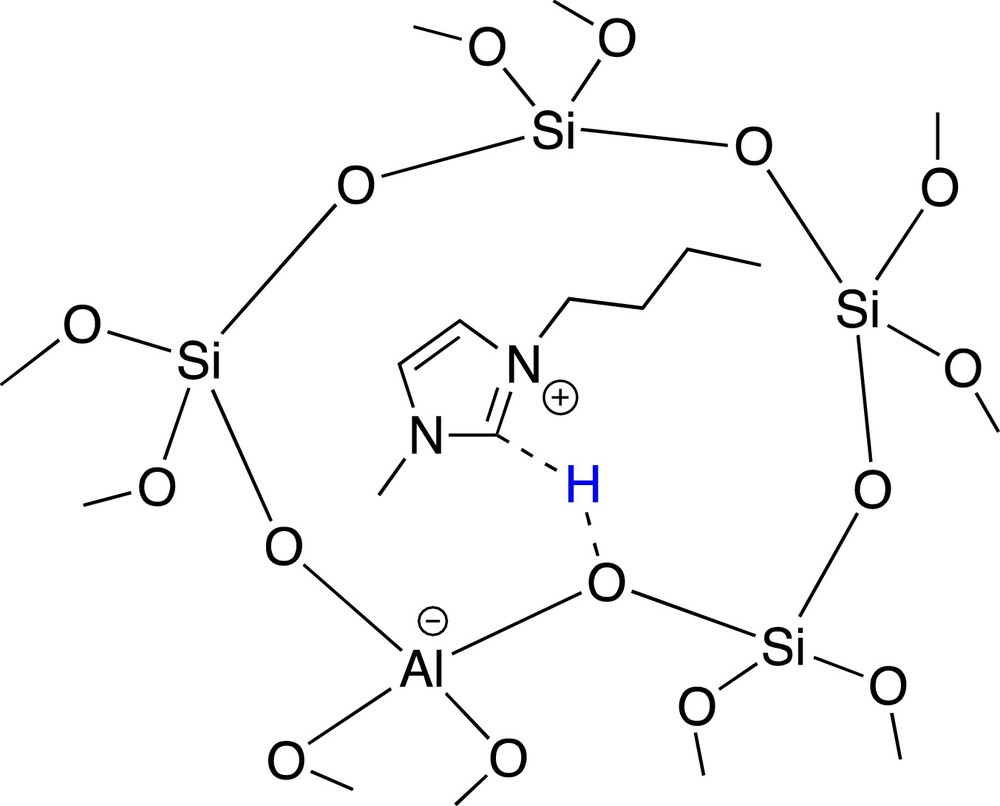

Whereas IL probably blocks the ZSM-5 pores, its presence in MOR and BEA frameworks gives rise to a reverse tendency. In the BEA framework, IL presence led to enhanced activity and to roughly ortho/para ratio = 1 (entries 5 and 6). IL/BEA composite activity might be related to the apparent acidity of bmim+ cation, as depicted in Fig. 3. This interaction through the protocarbenic hydrogen (relatively acid) has already been evidenced by theoretical calculations [5].

Relative acidity of the bmim+ in IL/BEA composite.

In contrast to IL/ZSM-5 composite, the negative zeolite framework charge is compensated by the ionic liquid in IL /BEA; and considering the wider pores of the BEA topology, no steric hindrance is envisaged.

DFT calculations were previously carried out at IEFPCM(H2O)/M06-2X/6-31++G**+ECP(Si, Al, Cl) level on the reaction between TCCA and benzene catalyzed by a zeolite cluster T5 model [8]. The possible organization of the aromatic substrate and TCCA chlorination agent in the vicinity of the zeolite surface can be easily performed within BEA or MOR zeolite pores.

4 Conclusions

The green chlorination reaction of toluene by TCCA was successfully catalyzed by immobilized IL both on CNF and in different zeolite structures. Despite low conversion is achieved with these barely acidic composites, a peculiar behavior was observed for ILs immobilized on CNF. Indeed a high selectivity (up to 36%) toward meta-chlorotoluene was achieved. While properly tailoring the nature of IL composites, the selectivity in chlorotoluene isomers was extremely different. One may therefore tune the reactivity of ILs by changing the support.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) for supporting the ANR-10-JCJC-0703 project (SelfAsZeo). The present project is also supported by the National Research Fund, Luxembourg (PL PhD grant No. 5898454). S. Ivanova acknowledges MEC for her Ramon y Cajal contract.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier