1 Introduction

Numerous measures to reduce anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, especially CO2, already exist, such as its capture and storage. Another solution is to develop a method for converting CO2 into valuable chemical compounds, such as methanol, methane or dimethylether [1–4]. The aim of this work is to transform CO2 into methanol by reduction with hydrogen produced by water electrolysis, using the electricity provided by decarbonated energies, such as nuclear and renewable energies. Beyond the valorisation of CO2, this process also allows one to provide the electrical grid with a management function. In fact, the production of hydrogen is correlated with the quantity of excess electricity from the network.

Methanol is produced in quantities over 50 million tons per year [5] and is present in many industrial sectors. It is used as a raw material for the synthesis of formaldehyde, one of the most important organic molecules (around 5 × 107 tons of formaldehyde produced per year) [6], for the synthesis of olefins [7,8], such as propylene and ethylene (biopolymer precursors). Methanol is also known as a fuel [7,9–11] either for fuel cells [12,13] or mixed with gasoline, or indirectly as a raw material for the synthesis of diesel, gasoline, dimethylether, hydrocarbons… Thus, the synthesis of methanol allows getting stable and easily stored carbon energy, as an alternative to fossil fuels.

At first, methanol was mostly produced by the catalytic hydrogenation of CO [14] with a feed gas of CO/H2 or CO/CO2/H2. In the 1990s, some studies comparing the reactivity of CO/H2 and CO2/H2 have shown that the hydrogenation of CO2 is faster than that of CO [15–17]. The same studies show that even starting from CO/CO2/H2 mixtures, methanol is mainly produced from the hydrogenation of CO2. Thereafter, in the early 2000s, the number of publications about CO2 hydrogenation increased.

The classical methanol synthesis catalysts were designed for CO/CO2/H2 and must be optimized and modified for the hydrogenation of CO2 without CO addition. The literature review clearly shows that copper is the favoured metal and highlights the importance of the presence of ZnO along with a good interface between Cu and ZnO [18] for this reaction, which increases respectively copper dispersion and CO2 adsorption. Other papers have also shown that there is a synergetic effect between Cu and ZnO by the combination of three different phenomena. First, the morphology of the Cu particles may change through a wetting/non-wetting effect of the Cu/ZnO system [19]. Secondly, the migration of ZnOx species in the surface of Cu particles is related to the creation of an active site, like a Cu–Zn surface alloy enhancing the activity of the Cu surface [20–23]. Finally, the synergetic effect is also induced by hydrogen dissociation on ZnO, which is a source of hydrogen storage [24,25].

Other metals, such as Au or Pd, and other supports have been also studied. Au–TiO2 leads to high CO2 conversion rates but low methanol selectivity. By adding ZnO, this catalyst becomes as efficient as Cu-based ones but it is clearly more expensive [26]. For Pd–CeO2 catalysts, it has been shown that a partial reduction of CeO2 [27] leads to an increase of the reactivity. The beneficial effect of the support was also discussed for Cu/ZnO-based catalysts. The addition of Al2O3 leads to better conversions and selectivities than that of Cu/ZnO. The addition of ZrO2 leads to an increase of the copper dispersion and is more interesting than Al2O3 because it is involved in the adsorption of CO2 [28]. The addition of ZrO2 leads to an increase in copper dispersion and is more interesting than Al2O3 as a support because it is involved in the adsorption of CO2 [28]. This higher metal dispersion is due to a large interfacial area of CuO and ZrO2 favoured by the formation of surface oxygen vacancies on the ZrO2 support [29]. This high interfacial area was as well discussed to play a role in the improvement of the methanol formation due to microcrystalline copper particles that are stabilised by interaction with an amorphous zirconia support [30]. A better adsorption of H2 was found with CeO2 [31], which is also known for its beneficial effect on the formation of methanol with CO/H2 [32], and by combining ceria and zirconia better methanol productivities were obtained, induced by a high hydrogen adsorption capacity and a higher Brønsted acidity attributed to the formation of Ce3+–O(H)–Zr4+ species [33]. Other supports, such as Ga2O3 and Cr2O3, do not improve copper dispersion, but can improve catalytic activity [34]. MgO reduces the sintering of copper and promotes activity, but at the expense of CH3OH selectivity [35].

The main objectives of our work are the synthesis and the characterization of efficient catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation into methanol and the development of reaction conditions leading to improved methanol productivity. The commonly used CuO–ZnO–Al2O3 catalyst was synthesized by two methods, sol–gel and co-precipitation synthesis, and then Al2O3 was substituted by other supports, such as ZrO2, CeO2 and CeO2–ZrO2, in order to have a better understanding of the support effect. These catalysts were tested at three temperatures 240, 260 and 280 °C at 50 bar total pressure and different Gas Hourly Space Velocity (GHSV values). Here are presented the effects of catalyst synthesis conditions, catalyst composition, reaction temperature and GHSV on the catalytic behaviour in CO2 hydrogenation into methanol.

2 Experimental

2.1 Catalyst preparation

A series of CuO–ZnO–Al2O3 catalysts containing 30% by weight of copper, 41 wt% of ZnO and 21 wt% of Al2O3 (ZnO/Al2O3 molar ratio of 2) were synthesized by pseudo sol–gel (30CuZn–ASG) and co-precipitation (30CuZn–A) methods in order to assess the impact of the preparation method on catalytic behaviour.

For pseudo sol–gel synthesis [36–39], the metallic precursors Cu, Zn and Al acetates were individually dissolved in propionic acid at 140 °C (0.12 M for Cu and 0.07 M for Zn and Al). These three solutions were mixed together and heated under reflux for 24 h. Propionic acid was then evaporated by vacuum distillation to obtain a resin.

For co-precipitation [40,41], two methods were tested by varying the zinc precursors, namely zinc oxide (30CuZn–AOX) or zinc nitrate (30CuZn–ANIT). Into a solution (1 M) of Cu nitrate, Zn oxide or nitrate and Al nitrate heated at 60–65 °C, a solution of Na2CO3 (1.6 M), used as a precipitating agent, was added until a pH of 6–6.5. The precipitate was aged for 3.5 h in the mother liquor, and then filtered, washed with water and dried for 5 days at 100 °C.

The resulting resins and powders were then calcined in air at different temperatures (300 °C, 400 °C, 500 °C) for 4 h with a heating ramp of 2 °C·min−1 to give fresh catalysts.

The catalysts with a modified composition CuZnM (M = Zr, Ce, CeZr) were synthesized by co-precipitation and calcined at 400 °C in the same way than 30CuZn–ANIT and also contain 30wt% of copper and 41 wt% of ZnO. The notation is exemplified as follows: 30CuZn–CZ (60:40) refers to a catalyst containing 30wt% of Cu, 41 wt% of ZnO completed by ceria and zirconia with a mass ratio of 60:40.

2.2 Catalyst characterization

Specific surface areas measurements were performed by nitrogen adsorption–desorption at –196 °C using the Brunauer–Emmet–Teller (BET) method on a Micromeritics ASAP 2420 apparatus. Samples were previously outgassed at 250 °C for 3 h to remove the adsorbed moisture.

Reducibility studies were performed by temperature-programmed reduction (TPR) on a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920 with 150 mg of fresh catalyst and a total gas flow rate of 50 mL·min−1 of 10 % H2 in Ar with a heating ramp of 10 °C·min−1 until 400 °C.

The metal surface area was determined by N2O reactive frontal chromatography [42] on a Micromeritics AutoChem II 2920 in 50 mL·min−1 of 2 % N2O in Ar. Approximately 400 mg of fresh catalyst were first reduced at 300 °C for 12 h under a flow of 50 mL·min−1 of 10 % H2 in Ar and then cooled to 50 °C after an Ar purge. The copper surface area was calculated by quantifying the amount of consumed N2O and assuming 1.46 × 1019 copper atoms per square meter [43].

The crystalline structure of the catalysts was determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) with a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer equipped with a LYNXEYE detector and a Ni filter for Cu Kα radiations over a 2θ range between 10 and 95° and a step of 0.016° every 0.5 s. The crystallite size was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation [44].

2.3 Catalytic activity

The carbon dioxide hydrogenation into methanol was performed in a fixed-bed reactor. The powdered catalyst was initially sieved to particle size fraction between 100–125 μm and was introduced in the tubular reactor without any addition of inert gas. The temperature of the reaction was controlled by a thermocouple located in the furnace and contacting the external walls of the reactor at the level of the catalytic bed. The gas flows were regulated by mass flow controllers in order to deliver a constant total flow rate of 40 mL·min−1 of H2/CO2/N2. The Gas Hourly Space Velocity (GHSV) was varied using 2500 h−1, 5000 h−1 and 10,000 h−1 by adjusting the mass of catalyst.

The catalyst was first reduced under H2 (6.18 mL·min−1) at 300 °C and 50 bar for 12 h with a ramp of 1 °C·min−1. After cooling the catalyst to 100 °C, CO2 hydrogenation was carried out under a flow of 35 mL·min−1 of H2:CO2 (3.89:1) and 5 mL·min−1 of N2 (as an internal standard) at different temperatures between 240 and 280 °C under 50 bar and a GHSV of 5000 h−1 or 10,000 h−1.

The analysis of the reaction products was performed in two steps. First the gas phases was analysed online every 30 min using a gas microchromatograph (Inficon 3000 Micro GC) equipped with a TCD detector and two columns: a PoraPlot Q column to separate N2, CO, CH4, CO2, CH3OH and a molecular sieve 5-Å column to separate N2, H2, CH4, CO. Secondly, the liquid phase collected in the trap during the reaction was recovered at the end of the reaction and then analysed offline using a gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies 6890 N Network GC Systems) with ZB-WAX Plus (Zebron) column to quantify methanol.

The conversions ( and ) and selectivities ( and SCO) were then determined by the total carbon balance of the gas phase and the liquid phase. The methanol productivity was calculated in the same way by two methods: one giving productivity per catalyst mass (gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1) and the other giving productivity per copper surface area (mgMeOH·m−2Cu·h−1).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization

3.1.1 CuO–ZnO–Al2O3 catalysts

The main characteristics of the fresh CuO–ZnO–Al2O3 catalysts are given in Table 1. Depending on the preparation method, the specific surface areas either lie between 30 and 42 m2·g−1 (sol–gel synthesis) or between 99 and 124 m2·g−1 (synthesis by co-precipitation). In all cases, the higher the calcination temperature, the lower the specific surface area. The higher specific surface areas of the catalysts prepared by co-precipitation are explained by high pore volumes (around 0.5 cm3·g−1). The mean pore volume diameter of these catalysts is around 20 nm, corresponding to interparticle porosity since the crystallite sizes calculated from XRD are around 10 nm and 12 nm for ZnO–Al2O3 and CuO, respectively. For the catalysts 30CuZn–ASG, the pore volume is much lower (0.1 cm3·g−1) and the mean particle size of the ZnO–Al2O3 support is around 26 nm, while the CuO crystallite size is 18 nm. As a consequence, the apparent density of catalysts prepared by sol–gel method is much higher than that of materials synthesized by co-precipitation, around 1.5 compared to 0.6 g·cm−3, respectively. Among the catalysts prepared by co-precipitation, the use of Zn nitrate instead of Zn oxide as Zn precursor does not lead to deep modifications of the catalyst.

Characterizations of the fresh 30CuZn–A and 30CuZn–ASG catalysts.

| Synthesis | Calcination temperature (°C) | Apparent density (g·cm−3) | BET | XRD – Crystallite size (nm) | |||

| SBETa (m2·g−1) | Dporeb (nm) | Vporec (cm3·g−1) | CuO | Support | |||

| 30CuZn–ASG | 300 | 1.36 | 42 | 8 | 0.09 | 18.9 | 26.1 |

| 400 | 1.66 | 37 | 16 | 0.10 | 18.5 | 26.4 | |

| 500 | 1.55 | 30 | 16 | 0.10 | 17.9 | 25.7 | |

| 30CuZn–AOX | 300 | 0.69 | 121 | 21 | 0.50 | 11.5 | 9.3 |

| 400 | 0.69 | 124 | 21 | 0.51 | 12.4 | 9.4 | |

| 500 | 0.69 | 99 | 23 | 0.45 | 15.6 | 9.8 | |

| 30CuZn–ANIT | 400 | 0.56 | 108 | 19 | 0.43 | 12.5 | 9.6 |

a Specific surface area.

b Pore diameter.

c Pore volume.

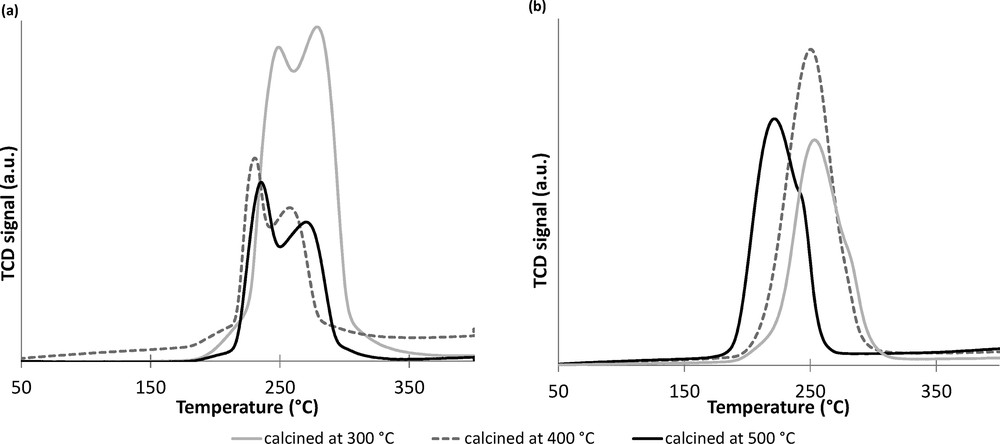

TPR profiles (Fig. 1a) show that for co-precipitated catalysts (using zinc oxide as zinc precursor), the reduction of copper oxide takes place in two steps: first with a peak of H2 consumption before 250 °C and secondly with a peak after 250 °C, probably because of different insertions or interactions between copper and the support [45]. This phenomenon is less perceptible for pseudo sol–gel catalysts (Fig. 1b). The increase of the calcination temperatures from 300 °C to 400 °C diminishes the copper oxide reduction temperature, suggesting that a higher calcination temperature facilitates the reduction of copper oxide [46] by diminishing the CuO–support interaction.

TPR profiles of fresh Cu–Zn–Al catalysts synthesized by (a) co-precipitation and (b) sol–gel method.

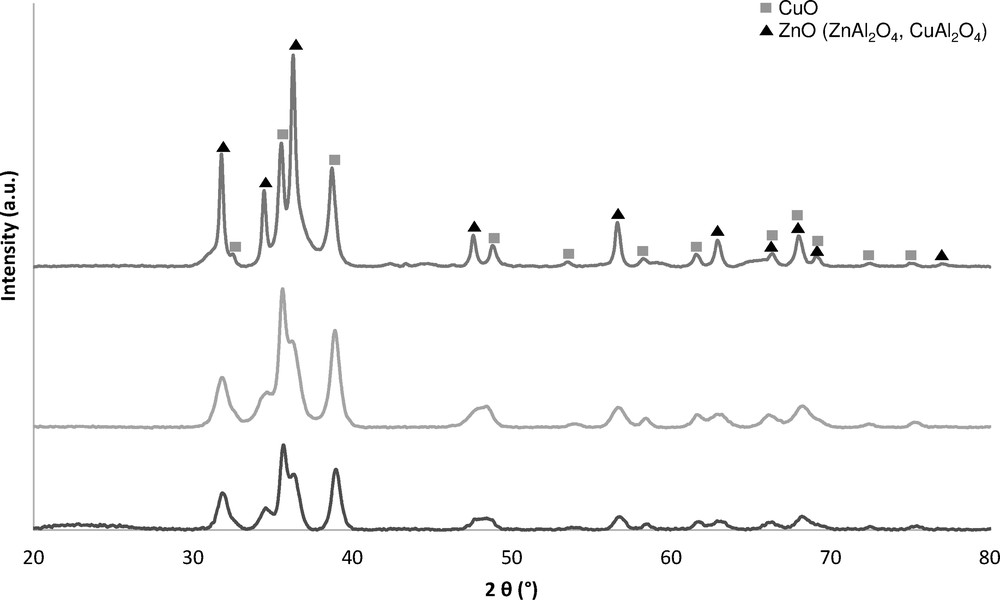

The crystalline structures of the catalysts after calcination are presented in Fig. 2. First of all, for the catalysts synthesized by co-precipitation with different zinc precursors, the same diffractograms and crystallite sizes (Table 1) are obtained. Secondly, diffraction peaks corresponding to copper oxide and zinc oxide are observed for pseudo sol–gel and co-precipitation synthesis. The aluminium oxide diffraction peaks are not observed, suggesting that this phase is in an amorphous [47,48] or mixed oxide state (ZnAl2O4, CuAl2O4) [49,50], assuming that these diffraction peaks overlap with those of ZnO. By comparing both methods, after calcination at 400 °C, a lower ZnO peak intensity (Fig. 2) is noticed for co-precipitation, which accounts for a better dispersion [32,47] in the catalyst structure compared to the pseudo sol–gel technique. The CuO crystallite sizes presented in Table 1 are 12.4 nm for 30CuZn–AOX and 18.5 nm for 30CuZn–ASG. The crystallite sizes of ZnO are 9.4 nm and 26.4 nm, respectively. These smaller crystallite sizes for co-precipitation can confirm a better dispersion of the active phase on the support [51]. However, another explanation for this significant difference of ZnO crystallite size could be the existence of different phases, as mentioned previously. It is possible that the pseudo sol–gel synthesis leads preferentially to mixed oxides (ZnAl2O4, CuAl2O4) compared to co-precipitation. Concerning the effect of calcination temperature, the CuO crystallite sizes clearly increase from 300 °C to 400 °C as well as from 400 °C to 500 °C, which can be explained by a higher sintering of copper [34], but only for the co-precipitated catalysts, supposing a better stability of the pseudo sol–gel catalysts.

XRD of the 30CuZn–A catalyst prepared by pseudo sol–gel and co-precipitation synthesis.

3.1.2 Support effects

The main characteristics of the catalysts synthesized with different support compositions are presented in Table 2 and compared to the classical catalyst 30CuZn–ANIT.

Characterizations of the fresh catalysts with different support composition.

| Catalyst | Cu (%) | Apparent density (g·cm−3) | Cu surface area (m2·gcata−1) N2O | BET | XRD – Crystallite size (nm) | |||

| SBETa (m2·g−1) | Dporeb (nm) | Vporec (cm3g−1) | CuO | Support | ||||

| 30CuZn–ANIT | 30 | 0.56 | 7.1 | 108 | 19 | 0.43 | 12.5 | 9.6 |

| 30CuZn–C | 30 | 0.53 | 4.2 | 24 | 42 | 0.13 | 15.8 | 4.5 (CeO2) 22.7 (ZnO) |

| 30CuZn–CZ (60:40) | 30 | 0.57 | 3.6 | 32 | 34 | 0.15 | 13.5 | 5.9 (CeO2) 23.7 (ZnO) |

| 30CuZn–CZ (20:80) | 30 | 0.48 | 7.5 | 58 | 37 | 0.35 | 10.6 | 12.4 (ZnO) |

| 30CuZn–Z | 30 | 0.54 | 12.7 | 61 | 22 | 0.22 | 10.2 | 9.7 |

a Specific surface area.

b Pore diameter.

c Pore volume.

The specific surface areas (Table 2) are 108 m2·g−1, 24 m2·g−1, 32 m2·g−1, 58 m2·g−1 and 61 m2·g−1 for 30CuZn–ANIT, 30CuZn–C, 30CuZn–CZ (60:40), 30CuZn–CZ (20:80) and 30CuZn–Z, respectively. The highest BET surface is observed for 30CuZn–ANIT, as Al2O3 permits a better dispersion of CuO–ZnO [40]. The other BET surface areas decreased as follows: 30CuZn–ANIT > 30CuZn–Z > 30CuZn–CZ (20:80) > 30CuZn–CZ (60:40) > 30CuZn–C. The BET surface is thus correlated with the amount of ZrO2 in the catalysts. The same behaviour is observed for the pore volumes, which decrease from 0.22 cm3·g−1 to 0.13 cm3·g−1 with decreasing the zirconia content. The mean pore diameters vary in the opposite way.

A similar apparent density, around 0.5 g·cm−3, was observed. This allows having the same catalyst mass during the catalytic tests, for all the catalysts of this series, which leads to an easier comparison of the catalytic behaviours.

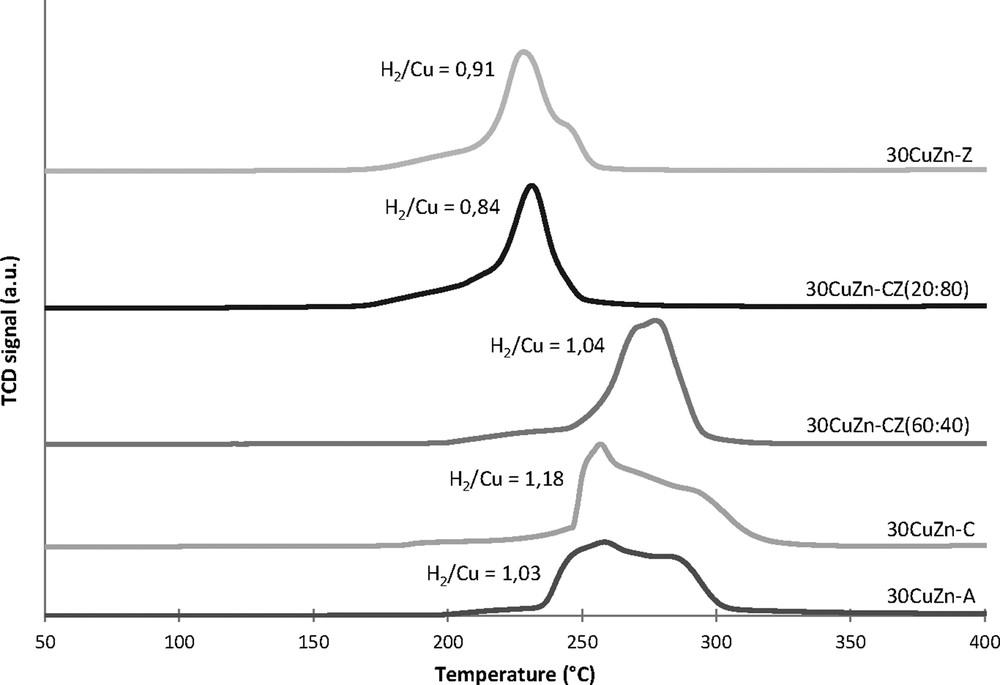

The reducibility of copper species was determined by TPR experiments and the results are presented in Fig. 3. For 30CuZn–ANIT catalyst, the TPR profile shows two reduction peaks, as previously discussed for 30CuZn–AOX (Fig. 1). The substitution of Al2O3 by ZrO2 modifies the reduction profile of the catalyst, leading to only one reduction peak and also shifting the peak of copper oxide reduction to a lower temperature, from 260 °C to 230°C, revealing that the presence of zirconia improves the reducibility of copper oxide [52], most probably due to a better dispersion of the copper oxide [53]. The same behaviour is observed for the ceria–zirconia catalyst with a high amount of zirconia: 30CuZn–CZ (20:80). When the amount of zirconia decreases from 80 wt% to 40 wt%, as for 30CuZn–CZ (60:40), the reduction temperature is increased to about 275 °C, leading to the same temperature range as for 30CuZn–C. However, the TPR profile of 30CuZn–CZ (60:40) shows only one peak compared to that of 30CuZn–C, with a shouldered peak suggesting two reduction steps as for 30CuZn–A. This profile can be explained by distinct copper oxide reduction steps, the first one at 260 °C related to the reduction of small crystalline CuO clusters, and the second one at 285 °C attributed to a strong interaction between copper ions and the support [45]. The catalysts containing high amounts of zirconia [30CuZn–Z and 30CuZn–CZ (20/80)] present the lowest H2/Cu molar ratio (respectively 0.91 and 0.84), while the catalysts with high amounts of ceria [30CuZn–C and 30CuZn–CZ (60/40)] show the highest H2/Cu molar ratio (respectively 1.18 and 1.04). These differences can be explained by the support effect, in which the partial reduction of ceria for 30CuZn–C and 30CuZn–CZ (60/40) leads to H2/Cu ratios higher than 1.

TPR profiles of fresh catalysts with different support compositions.

The copper surface areas calculated by N2O reactive frontal chromatography are given in Table 2. They are respectively of 7.1 m2·gcata−1, and 12.7 m2·gcata−1 for 30CuZn–ANIT and 30CuZn–Z. The highest copper surface area is observed for 30CuZn–Z and not for 30CuZn–ANIT, suggesting that a high copper surface area is not directly correlated with a high BET surface. The other Cu0 surface areas (Table 2) decrease according to: 30CuZn–Z > 30CuZn–CZ (20:80) > 30CuZn–C ≥ 30CuZn–CZ (60:40). This distribution is correlated with the amount of ZrO2 in the catalysts following the same tendency as the BET surface shown previously. These results clearly show that zirconia leads to higher copper surface areas and copper dispersion, corroborating the literature reviews in which the substitution of Al2O3 by ZrO2 improves copper dispersion [54–56]. They also clearly show the negative effect of ceria [57] on the main characteristics of the catalyst.

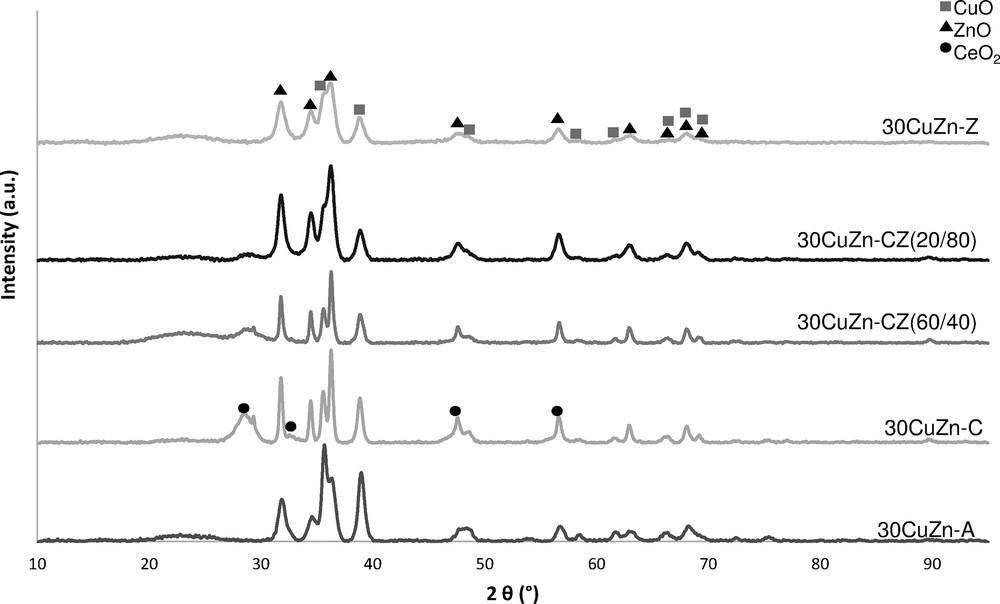

The crystalline structures of the catalysts after calcination are presented in Fig. 4. Diffraction peaks corresponding to copper oxide and zinc oxide are observed for all catalysts. The cerium oxide diffraction peak corresponding to (1 1 1) plane is observed for a 2θ value between of 28.5° and 28.7° for ceria-containing catalysts. The zirconium oxide diffraction peaks are not observed, suggesting that this phase is in an amorphous or a micro-crystallite state [56]. The intensities of the diffraction peaks corresponding to copper oxide and zinc oxide decrease for 30CuZn–Z compared to 30CuZn–ANIT, suggesting that the substitution of Al2O3 by ZrO2 improves the dispersion of copper and zinc oxides [55]. By comparing the crystallite sizes presented in Table 2, the presence of a high amount of ZrO2 also decreases the copper and zinc oxide crystallite sizes. The catalysts containing ceria clearly show higher CuO and ZnO crystallite sizes, in accordance with the lower copper surface and BET surface area. The CeO2 lattice parameter calculated from the diffraction peak around a 2θ value of 28.6° is 5.38–5.40 Å for every ceria-containing catalyst, corresponding to the cubic lattice parameter of CeO2. For 30CuZn–CZ (60:40) and 30CuZn–CZ (20:80), the solid solution of CZ is thus not formed. This result can also explain the previous characterizations of 30CuZn–CZ catalysts corresponding to lower copper surface areas and BET surfaces than 30CuZn–Z.

XRD of fresh catalysts with different support compositions.

3.1.3 Precipitation pH study

To understand the differences of characterization, especially concerning copper surface and BET surface area, an investigation of the catalyst preparation was performed, particularly on the precipitation pH of each salt. These results, presented in Table 3, show the following order for precipitation pH: ZrOCO3 < Al2(CO3)3 < CuCO3 < ZnCO3 < Ce(CO3)1.5.

Precipitation pH of each salt.

| Compound | Precipitation pH |

| ZrO(CO3) | 0.14–1.6 |

| Al2(CO3)3 | 2.15–2.6 |

| Cu(CO3) | 2.30–3.15 |

| Zn(CO3) | 3.3–4.5 |

| Ce(CO3)1.5 | 4.0–4.1 |

For the synthesis of 30CuZn–C, CuCO3 precipitated first without any support. On the contrary, for 30CuZn–Z ZrOCO3 precipitated first and then, CuCO3 precipitated on ZrOCO3. All the results account for a better Cu dispersion and higher copper and BET surface area of 30CuZn–Z compared to 30CuZn–C. For 30CuZn–CZ catalysts, ZrOCO3 and Ce(CO3)1.5 do not precipitate simultaneously, which can explain the absence of a CexZr(4−x)O8 solid solution. Therefore, some modifications of the co-precipitation method will be done, especially in order to have a constant pH [58–60] for the duration of the synthesis, higher than 4.5 in order to precipitate all the salts at the same time. With this good control of the synthesis, a better interface between Cu/ZnO and Cu/support is also expected.

3.2 Carbon dioxide hydrogenation

3.2.1 Thermodynamic simulation

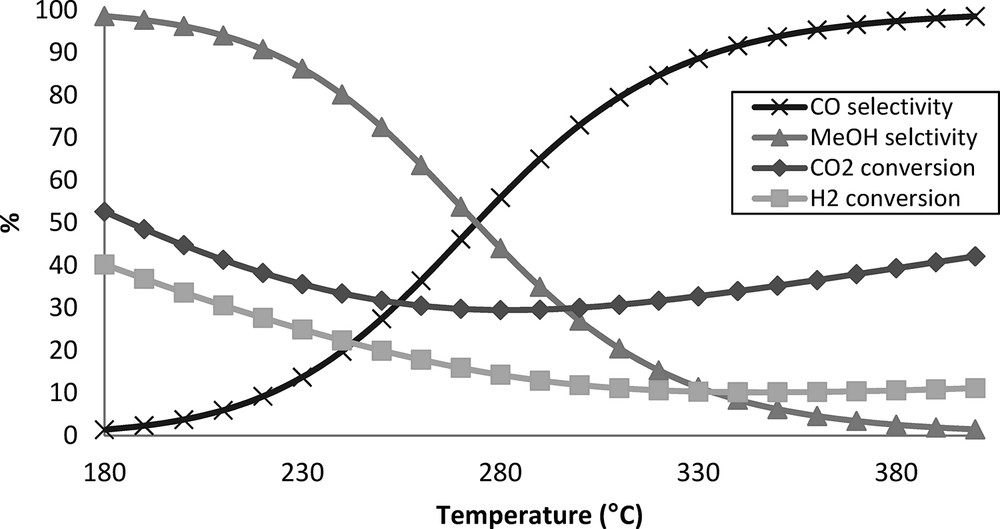

Thermodynamic calculations were performed using ProSimPlus process simulation software, with a Gibbs reactor. The various reactions that occur are the reaction of carbon dioxide hydrogenation into methanol (1), the reaction of reverse water–gas shift (2) and the reaction of carbon monoxide hydrogenation into methanol (3). The products that can be formed from this reaction mixture [according to the reactions (1–3)] have been identified as methanol, carbon monoxide, and water. The reagents and products composed the thermodynamic system. Thus, the H2 and CO2 conversion as well as the methanol and CO selectivities were calculated and displayed in Fig. 5.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Thermodynamic equilibrium versus temperature, at 50 bar, with H2/CO2 = 3.89.

The same operating conditions than for our catalytic tests were used, namely a pressure of 50 bar with a total gas flow rate of 40 mL·min−1 and a molar composition of H2:CO2:N2 3.89:1:0.3. The temperature was varied between 180 and 400 °C. With a temperature increase of 70 °C (180 to 250 °C), the equilibrium conversions decrease by about 20%. After 290 °C and 370 °C for CO2 and H2, respectively, the conversions start to increase again slowly. This increase of CO2 conversion is correlated with a high production of CO with a selectivity of almost 100 %. CH3OH selectivity decreases from 99 % to 50 % during a temperature increase by 95 °C (180 to 275 °C), until equality is reached with CO formation at 275 °C. At higher temperature, methanol selectivity decreases to almost 0 % at the benefit of CO selectivity when approaching 400 °C. These results clearly indicate that the best H2 and CO2 conversions and the optimal CH3OH selectivity are obtained at low temperatures.

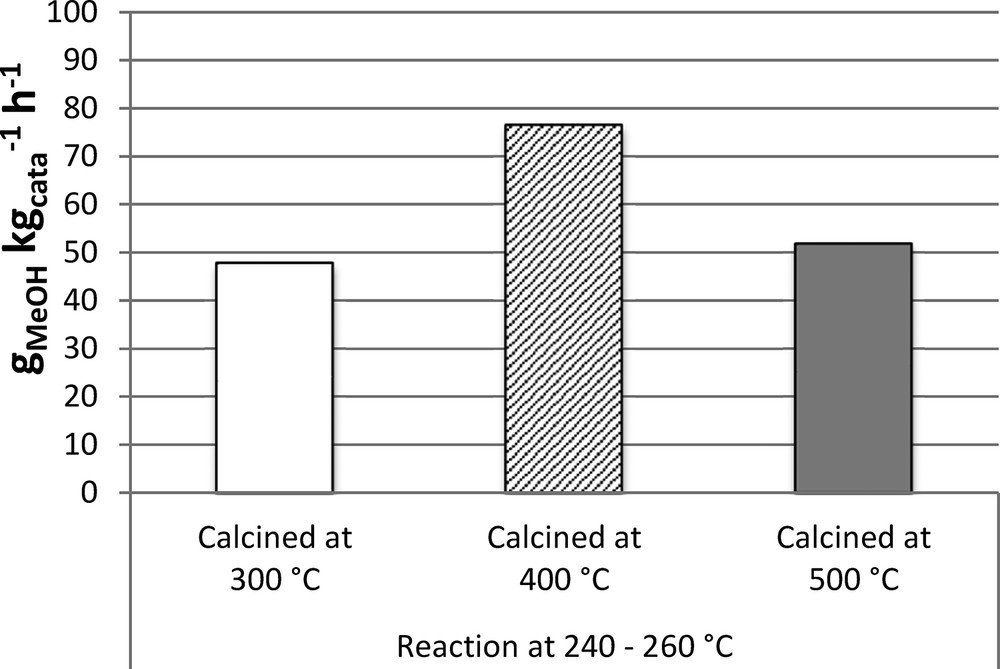

3.2.2 Catalytic activity: effect of calcination temperatures

The results obtained for 30CuZn–ASG pseudo sol–gel catalysts in CO2 hydrogenation reaction at 240, 260 and 280 °C at 50 bar and with a GHSV of 5000 h−1 are presented in Table 4. Firstly, the influence of reaction temperature on catalytic activity was studied by focusing on the catalyst calcined at 400 °C. The catalytic results indicate that increasing the temperature of the reaction from 240 to 260 °C leads to better conversions and similar MeOH selectivity. However, increasing the temperature of the reaction to 280 °C does not improve either conversion or methanol selectivity and even leads to a decrease of methanol selectivity in favour of CO formation. Moreover, at 280 °C, the results approach thermodynamic equilibrium, therefore increasing further the temperature; they will be limited by thermodynamics, without improvement of H2 and CO2 conversions and MeOH selectivity. Consequently, the reaction at 260 °C gives the best compromise between good H2 and CO2 conversions and low CO production combined with good methanol selectivity. Secondly, the influence of calcination temperature on catalytic activity was investigated by comparing the average results at 240 and 260 °C for CO2 hydrogenation (Fig. 6). Catalysts calcined at 300 and 500 °C with different conversions and selectivities show finally similar productivities, around 50 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1. The best methanol productivity is then obtained with the catalyst calcined at 400 °C with a maximum of 92 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 produced at 260 °C.

Catalytic results of 30CuZn–ASG in CO2 hydrogenation reaction at 50 bar and a GHSV of 5000 h−1.

| Calcination | Catalyst mass (mg) | Reaction temperature (°C) | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (%) | MeOH productivity | ||

| H2 | CO2 | MeOH | CO | (gMeOH kgcata−1 h−1) | |||

| Calcined at 300 °C | 720 | 240 | 2.4 | 5.3 | 57 | 43 | 23 |

| 260 | 8.4 | 15.8 | 55 | 45 | 68 | ||

| Calcined at 400 °C | 720 | 240 | 8.1 | 18.1 | 44 | 56 | 61 |

| 260 | 12.1 | 24.6 | 48 | 51 | 92 | ||

| 280 | 11.1 | 25.1 | 37 | 62 | 71 | ||

| Calcined at 500 °C | 720 | 240–260 | 6.7 | 13.9 | 48 | 52 | 52 |

| 280 | 9.3 | 19.7 | 45 | 55 | 68 |

CH3OH productivity at 240 and 260 °C at 50 bar and a GHSV of 5000 h−1 for 30CuZn–ASG.

3.2.3 Effect of GHSV

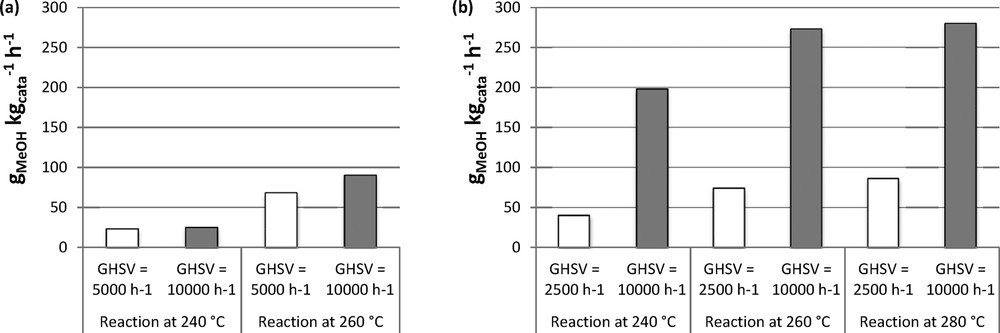

The influence of GHSV on methanol productivity was studied by varying the catalyst mass under the same flow of reactants. The results obtained for 30CuZn–ASG calcined at 300 °C at a GHSV of 5000 h−1 and 10,000 h−1 are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. At a reaction temperature of 260 °C, when GHSV is increased from 5000 h−1 to 10,000 h−1 for 30CuZn–ASG calcined at 300 °C, the conversions decrease from 8 % to 5 % for and from 16 % to 8 % for , respectively. On the contrary, methanol selectivity increases from 55 % to 71 %, leading to a rise of methanol productivity from 68 gMeOH kgcata−1·h−1 at 5000 h−1 to 90 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 at 10,000 h−1. The same observations are made for other reaction temperatures and other catalysts. As shown in Fig. 7, a higher GHSV leads to higher methanol productivity for 30CuZn–AOX co-precipitated catalyst too: at 260 °C, an increase from 74 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 at 2500 h−1 to 273 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 at 10,000 h−1 is observed. Apart from increasing methanol productivity, another advantage of increasing GHSV lies in reaction conditions that are further away from thermodynamic equilibrium concerning the conversions. Thus, the thermodynamic limitation previously discussed in Section 3.2.2 is reduced, allowing us to assess more clearly the effects of the various changes in the catalysts.

Catalytic results of 30CuZn–ASG and 30CuZn–A at 50 bar and a GHSV of 10,000 h−1.

| Catalyst | Catalyst mass (mg) | Reaction temperature (°C) | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (%) | MeOH productivity | ||

| H2 | CO2 | MeOH | CO | (gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1) | |||

| 30CuZn–ASG calcined at 300 °C | 360 | 240 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 67 | 32 | 25 |

| 260 | 5.3 | 8.2 | 71 | 27 | 90 | ||

| 280 | 7.1 | 14.0 | 53 | 46 | 115 | ||

| 30CuZn–AOX | 166 | 240 | 6.3 | 12.9 | 46 | 54 | 198 |

| 260 | 9.5 | 20.8 | 39 | 61 | 273 | ||

| 280 | 10.5 | 24.0 | 35 | 65 | 280 | ||

| 30CuZn–ANIT | 130 | 240 | 3.4 | 6.5 | 59 | 41 | 166 |

| 260 | 7.1 | 15.5 | 42 | 58 | 277 | ||

| 280 | 8.5 | 19.5 | 37 | 63 | 311 |

Influence of GHSV on CH3OH productivity at different temperatures at 50 bar for (a) 30CuZn–ASG and (b) 30CuZn–AOX.

3.2.4 Effect of the synthesis method

In order to find the best synthesis method for our catalysts, the catalytic results obtained at a GHSV of 10,000 h−1 are detailed in Table 5 and compared. The conversions are higher for 30CuZn–AOX than for 30CuZn–ASG at each reaction temperature. Although the methanol selectivity is lower for 30CuZn–AOX (at 260 °C, ) than for 30CuZn–ASG (at 260 °C, ), methanol productivity is clearly better, with a maximum of 280 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 at 280 °C for 30CuZn–AOX compared to 115 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 for 30CuZn–ASG. Concerning the zinc salt used for co-precipitation, methanol productivity is slightly higher for the catalyst prepared from zinc nitrate. At 280 °C, methanol productivity is 311 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 against 280 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 for the catalyst prepared from zinc oxide. This difference can be explained by a lower apparent density of 30CuZn–ANIT.

In view of these results, co-precipitated catalysts appear clearly more active than pseudo sol–gel catalysts, regardless of the zinc salt used for the co-precipitation. This is why for our following work, the catalysts were synthesized by co-precipitation.

3.2.5 Effect of the composition of the support

The activity of the commonly used catalyst 30CuZn–ANIT (prepared by co-precipitation with zinc nitrate) was compared to 30CuZn–Z, in order to have a better understanding of the support effects. The details of the catalytic results obtained at a GHSV of 10,000 h−1 are given in Table 6.

Catalytic results of catalysts with different support compositions.

| Catalyst | Catalyst mass (mg) | Reaction temperature (°C) | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (%) | MeOH productivity | ||

| H2 | CO2 | MeOH | CO | (gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1) | |||

| 30CuZn–ANIT | 134 | 240 | 3.4 | 6.5 | 59 | 41 | 166 |

| 260 | 7.1 | 15.5 | 42 | 58 | 277 | ||

| 280 | 8.5 | 19.5 | 37 | 63 | 311 | ||

| 30CuZn–C | 128 | 240 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 260 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 46 | 54 | 143 | ||

| 280 | 5.3 | 12.8 | 37 | 63 | 210 | ||

| 30CuZn–CZ (60:40) | 137 | 240 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| 260 | 4.5 | 9.7 | 41 | 59 | 166 | ||

| 280 | 4.4 | 15.0 | 22 | 78 | 137 | ||

| 30CuZn–CZ (20:80) | 115 | 240 | 3.5 | 7.3 | 51 | 49 | 183 |

| 260 | 5.3 | 12.7 | 36 | 64 | 224 | ||

| 280 | 7.8 | 20.4 | 27 | 72 | 277 | ||

| 30CuZn–Z | 130 | 240 | 6.8 | 14.3 | 45 | 55 | 283 |

| 260 | 6.8 | 17.5 | 35 | 65 | 260 | ||

| 280 | 9.8 | 23.2 | 33 | 67 | 331 |

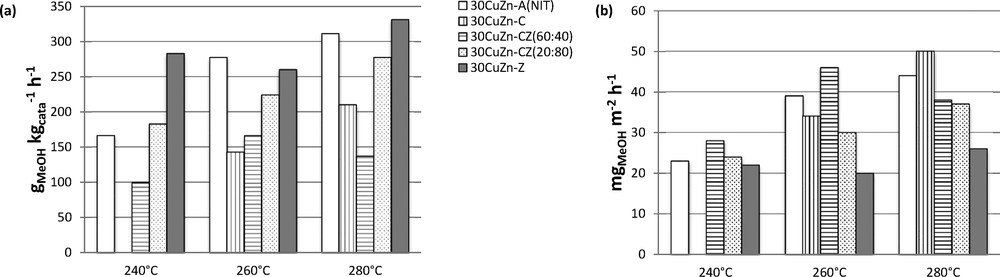

The H2 and CO2 conversion rates increase for 30CuZn–Z compared to 30CuZn–ANIT, especially at 240 °C, from 3.4 % and 6.5 % to 6.8 % and 14.3 %, respectively. This difference is less perceptible at higher temperature. Methanol selectivity decreases with increasing temperature. Methanol productivity (Fig. 8a) is also increased, principally at low temperatures. As expected, by modifying the support, productivity is increased. The higher activity is correlated with a higher copper surface of the 30CuZn–Z catalyst (Table 2). This beneficial effect of ZrO2 compared to Al2O3 can be explained by the involvement of ZrO2 in CO2 adsorption [28].

CH3OH productivity at different temperatures under 50 bar and a GHSV of 10,000 h−1 (a) per mass unit of catalyst and (b) per unit of copper surface area.

The ceria-containing catalyst 30CuZn–C does not show any conversion at 240 °C. This catalyst has conversion rates about 3% and 7%, respectively, for and at 260 °C. Consequently, by comparing with the results for 30CuZn–ANIT, this catalyst leads to lower conversion rates, showing a negative effect of the substitution of Al2O3 with CeO2. No clear difference in methanol selectivity was observed. As for the conversions, a negative effect is also noticed for methanol productivity per catalyst mass, as presented in Fig. 8a. 30CuZn–C compared to 30CuZn–Z leads to the same conclusions as the comparison with 30CuZn–ANIT, namely a better methanol selectivity but lower conversion rates; therefore, the 30CuZn–C catalyst has lower methanol productivity per catalyst mass (Fig. 8). However, by calculating methanol productivity per metallic copper surface area (Fig. 8b), the opposite effect is noticed, namely a beneficial effect of ceria with the highest productivity (50 mgMeOH·m−2Cu·h−1) and a negative effect of zirconia with lower productivity (26 mgMeOH·m−2Cu·h−1), especially at higher temperature (280 °C). This beneficial effect of ceria is in accordance with observations from the literature for methanol synthesis from CO/H2 [32].

Another type of catalyst containing CeO2 and ZrO2 (30CuZn–CZ) with different amounts of CeO2:ZrO2 (60:40 and 20:80 wt%) was also synthesized and tested. By comparing the catalytic results at 280 °C, these catalysts show lower conversions and methanol selectivities (Table 6) than 30CuZn–Z and 30CuZn–C, and therefore, lower methanol productivity by increasing the CeO2 amount (Fig. 8a). However, like previously, the same beneficial effect of CeO2 is observed for the methanol productivity per surface area of metallic copper (Fig. 8b). This methanol productivity increases with the amount of CeO2. Consequently, it would be interesting to increase the surface area of metallic copper for catalysts containing CeO2, in order to see if this can improve methanol productivity per mass of catalyst. To reach that goal, 30CuZn–CZ should be synthesized with a CexZr(4−x)O8 solid solution to see if it can combine the beneficial effects of ZrO2 and CeO2 presented above. Bell et al. [33] studied the effect of a CexZr(1−x)O2 solid solution on methanol synthesis and found that the incorporation of CeO2 into ZrO2 increases methanol productivity from 0.136 gMeOH·gcata−1·h−1 to 0.416 gMeOH·gcata−1·h−1, respectively, for 30Cu–ZrO2 and 30Cu–CeO2–ZrO2 at 250 °C, 30bar and H2/CO = 2.

In summary, the best methanol productivity per catalyst mass was obtained with 30CuZn–Z with 331 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1. In the literature, similar catalysts were also studied. With a 25Cu–ZnO–ZrO2 catalyst, Arena et al. [61] have obtained a methanol productivity of 65 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 at 200 °C, 10 bar, GHSV of 8800 NL·h−1·kgcata−1 and H2/CO2 = 3. In another publication [62] about a Cu–ZnO–ZrO2 catalyst with 45 wt% of Cu, methanol productivity was improved to 305 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 at 240 °C, 30 bar, GHSV of 10,000 NL·h−1·kgcata−1 and H2/CO2 = 3. By modifying some parameters like increasing GHSV at 80,000 NL·h−1·kgcata−1, a clearly higher methanol productivity of 1200 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 was achieved. Saito et al. [34] have also published results from a 50Cu–ZnO–ZrO2 catalyst leading to 665 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 of methanol productivity at 250 °C, 50 bar, GHSV of 10,000 L h−1 and H2/CO2 = 3. Compared to these results, our catalyst seems to be promising, even if it still needs to be optimized.

4 Conclusions

Two synthesis methods and the influence of the calcination temperature have been investigated in order to understand the most efficient conditions leading to the best methanol productivity: namely a catalyst synthesized by co-precipitation and calcined at 400 °C. Some operating conditions have been investigated, such as the influence of reaction temperature and GHSV. It has been concluded that the optimal conditions for the hydrogenation of carbon dioxide into methanol using 30CuZn–A were a reaction temperature of 260 °C and a GHSV of 10,000 h−1.

The effect of the support's composition on the methanol synthesis reaction from CO2/H2 has been also studied. The best methanol yields were obtained with catalysts without ceria. The copper dispersions were much lower for ceria-containing materials. Nevertheless, for these catalysts, the productivity of methanol per metallic copper surface area increased with the ceria content.

In summary, the best results were obtained with a 30CuO–ZnO–ZrO2 catalyst synthesized by co-precipitation and calcined at 400 °C. This catalyst presents a good CO2 conversion rate (23%) with 33% of methanol selectivity, leading to a methanol productivity of 331 gMeOH·kgcata−1·h−1 at 280 °C under 50 bar and a GHSV of 10,000 h−1.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the ANR for financial support (project Vitesse2 No. ANR-10-EESI-06).