1. Introduction

Microelectronic technology continues to advance in the 21st century, with an increase in the number of microelectronic devices and a higher consumer demand for power sources. Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have clear and obvious advantages and continue to dominate the market [1, 2, 3, 4]. Transition metal oxides were considered for LIB anode materials in early 2000 due to their high capacities stemming from conversion reaction mechanisms [5, 6, 7]. Fe3O4 was among these early studied anode materials with a high capacity (theoretical value 926 mAh⋅g−1) [8, 9, 10]. However, during cycling, Fe3O4 expands and breaks, causing rapid loss of capacity. Additionally, the conductivity of Fe3O4 is poor [11]. Carbon coating was found to help alleviate these problems, both addressing Fe3O4 volume expansion during cycling and preventing particle agglomeration [12, 13, 14]. More importantly, the carbon layer not only improved the conductivity of the electrode but also stabilized the solid electrolyte interface (SEI), which greatly improved the cycle life and rate capability of LIBs [15, 16, 17]. Further research in materials design pushed for Fe3O4 with a porous or hollow structure, which improves electrode reversibility and active material/electrolyte contact [18, 19, 20]. Recently, Wang et al. reported a novel Fe3O4@Carbon yolk–shell nanorod anode material by a one-pot method. The voids in the Fe3O4@Carbon core–shell nanorods were beneficial for volume expansion and allowed the Fe3O4@Carbon-based electrode to maintain its structural integrity during repeated Li+ insertion/extraction. Additionally, carbon coating on Fe3O4 provided a stable SEI film. The Fe3O4@Carbon composites exhibited high mechanical stability and excellent cycling performance (954 mAh⋅g−1 200 cycles at 0.5 A⋅g−1) [21]. Liu et al. prepared micron-sized porous Fe3O4 spheres through the solvothermal and calcination methods. Carbon-covered Fe3O4 porous microspheres demonstrated an outstanding reversible capacity (747 mAh⋅g−1 after 50 cycles at 0.1 A⋅g−1) and good rate capacity (255 mAh⋅g−1 at 1.6 A⋅g−1) [22]. Zhou et al. synthesized uniform porous Fe3O4@Carbon microspheres by a hydrothermal method. These microspheres showed good electrochemical performance (609 mAh⋅g−1 after 200 cycles at 0.2 A⋅g−1) [23].

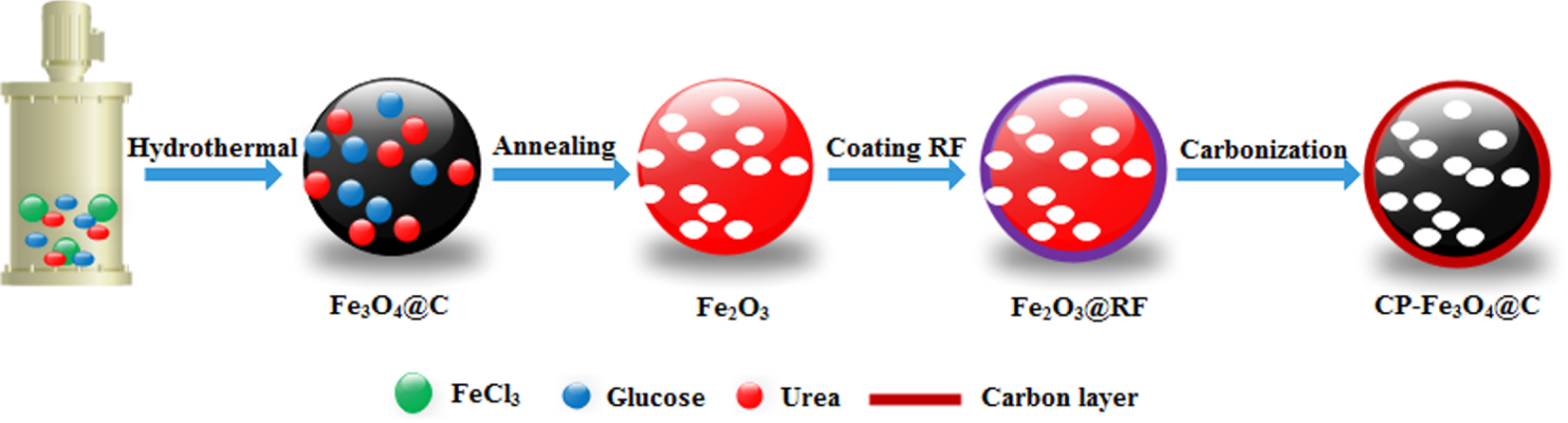

In this work, novel core–shell porous Fe3O4@C microspheres (CP-Fe3O4@C) were successfully designed and constructed by simple hydrothermal and carbonization methods. First, the Fe3O4@GU microspheres were synthesized using ferric chloride as an iron source and common chemicals glucose and urea as filler particles; the Fe3O4@GU composite was heat-treated in oxygen atmosphere to obtain the porous Fe2O3 microspheres. Second, resorcinol-formaldehyde (RF) resin was applied to porous Fe2O3 microspheres to obtain core–shell Fe2O3@RF microspheres, which were then used for the fabrication of CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres by one-step carbonization without a surfactant. The material synthesized through our straightforward method shows excellent performance as an anode material for LIBs.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Preparation of Fe3O4@GU

The Fe3O4@GU microspheres were prepared by a simple hydrothermal technique. Briefly, 2.13 g of ferric chloride (FeCl3), 2.0 g of glucose (C6H12O6) and 2.1 g of urea (CH4N2O) were added to 90 mL of deionized (DI) water and stirred. The resulting orange solution was placed into a 200 mL stainless steel Teflon-lined autoclave, heated at 200 °C for 6 h and then cooled to ambient temperature. The black Fe3O4@GU microspheres were washed with DI water thrice and dried at 60 °C for 12 h.

2.2. Preparation of porous Fe2O3

The Fe3O4@GU microspheres were heated at 500 °C in oxygen for 4 h, after which the furnace was cooled to the ambient temperature naturally. The bright orange porous Fe2O3 microspheres were washed with DI water thrice and dried at 60 °C for 12 h.

2.3. Preparation of CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres

A mixture containing 15 mL of DI water and 15 mL of ethanol was used to disperse porous Fe2O3 microspheres. Then, 2 mL of formaldehyde and 0.8 g of resorcinol were added, and the whole mixture was stirred for 30 min. The mixture was then transferred into a 100 mL stainless steel Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 100 °C for 36 h. The resulting material (which was Fe2O3@RF composite) was calcined at 500 °C for 4 h under N2 at a heating rate of 2 °C⋅min−1 to produce CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres. A schematic of the the preparation process for CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres is shown in Figure 1.

Synthesis flow chart of the CP-Fe3O4@C composite.

2.4. Material characterization

Crystalline phases were confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using Cu Kα radiation (𝜆 = 0.15406 nm) by a D8 type advanced diffractometer (40 kV and 30 mA). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed at 280 eV using ESCALAB 250Xi operated using Al Kα radiation as an excitation source. Morphology and microstructure were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, Merlin Compact) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, G2F20). Raman spectra were recorded using the Bruker-Senterra spectrometer with 514 nm laser excitation. Sample weight losses were measured by thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA, HCT-3). The analysis was performed in air in a range of 30 to 800 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C⋅min−1. The surface area of the CP-Fe3O4@C composite was measured by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method (Autosorb-IQ). Pore sizes were obtained from the corresponding nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda formula.

2.5. Electrochemical measurements

Anodes were prepared by mixing the active materials with conductive acetylene black and poly-vinylidene fluoride (PVDF) binder at a ratio of 8:1:1. The N-methyl pyrrolidone solvent (1.0 mL) was added to prepare slurry, which was applied to a copper foil and dried at 80 °C for 12 h. Coin cells (with standard size 2032) were assembled in a glove box under Ar atmosphere. Metallic Li was used as the counter electrode. The LiPF6 (1.0 M) dissolved in a 1:1 ethylene carbonate:dimethyl carbonate mixture was used as the electrolyte. Galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements at various current densities were recorded using NEWARE CT-4008 (Shenzhen). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was measured using an electrochemical workstation (Solartron 1287) from a potential of 0.01 to 3.00 V at a 0.1 mV⋅s−1 sweep rate. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy was conducted on the electrochemical workstation (Solartron 1287) from 0.01 Hz to 100 kHz at a perturbation of 5 mV AC.

3. Results and discussion

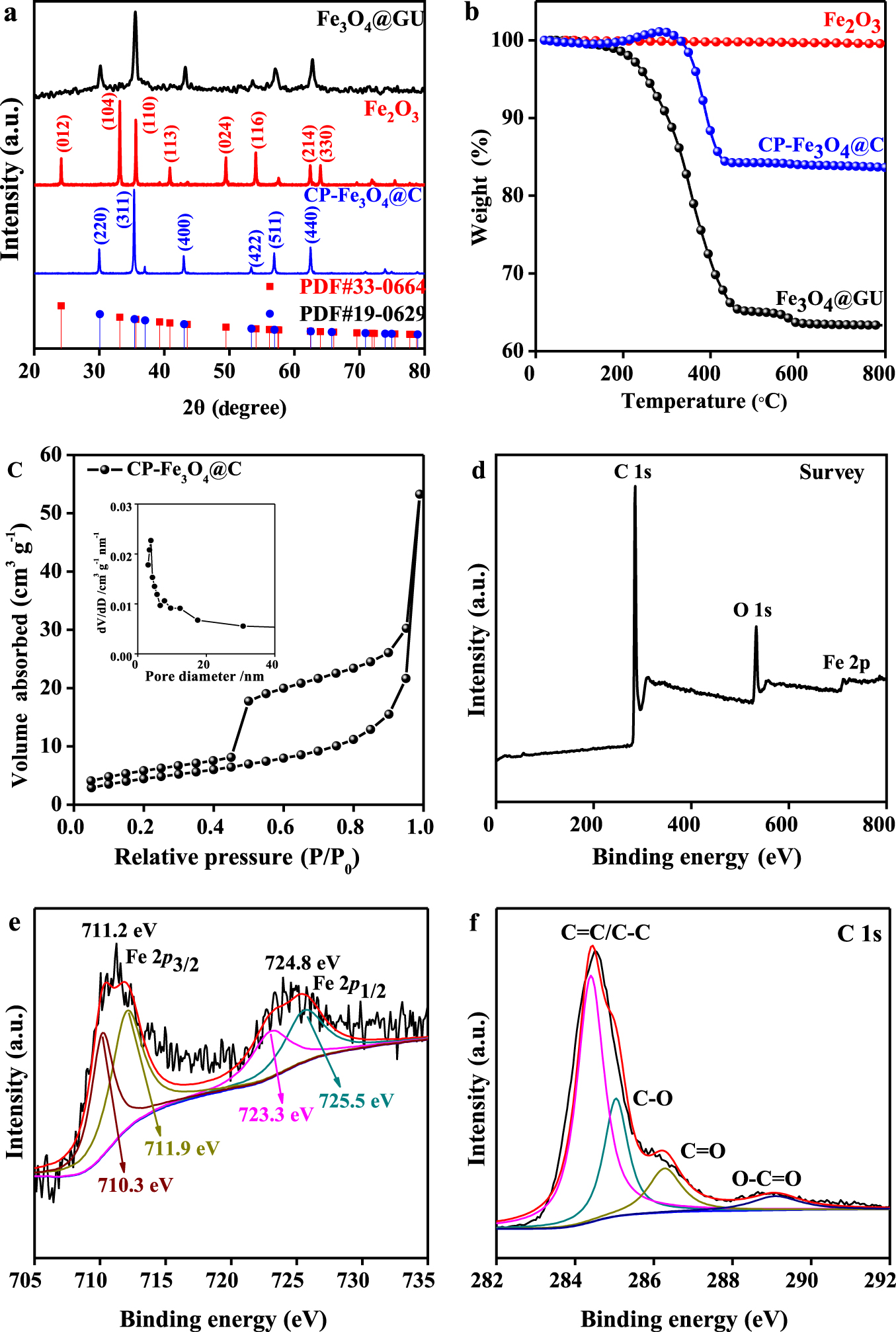

As-prepared Fe3O4@GU, Fe2O3 and CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres were characterized by XRD (Figure 2a). The strong reflections of Fe2O3 microspheres observed at 2𝛩 = 24.2, 33.2, 35.7, 40.9, 49.5, 54.0, 62.4 and 64.0° correspond to the (012), (104), (110), (113), (024), (116), (214) and (330) planes of hematite (JCPDS 33-0664) [24]. The XRD of Fe3O4@GU and CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres showed several peaks that are consistent with the face-centered Fe3O4 phase (JCPDS 19-0624) [12, 25]. In addition, no peaks of Fe2O3 were found in the diffraction peak of CP-Fe3O4@C, indicating that Fe2O3 was converted to Fe3O4. The carbon content analyses for Fe3O4@GU, Fe2O3 and CP-Fe3O4@C materials are shown in Figure 2b. Fe2O3 demonstrated almost no carbon weight loss and was corroborated by the XRD showing that only a Fe2O3 phase was present in this sample. There was rapid weight loss for Fe3O4@GU and CP-Fe3O4@C occurring from 200 to 400 °C, which was attributed to the decomposition of the carbon layer. With this weight loss, it was determined that the carbon content values for the Fe3O4@GU and CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres were 37.61% and 17.35%, respectively.

Sample characterization. (a) XRD pattern, (b) TGA pattern, (c) nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms and pore size distribution curve (inset), XPS spectra of the CP-Fe3O4@C (d) survey, (e) Fe 2p, (f) C 1s.

Raman spectra showed the presence of carbon in the CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres (see Supplementary Figure S1), indicated by the presence of two broad peaks at 1349 and 1587 cm−1, which correspond to D and G bands. These bands are assigned to sp3 disordered and sp2 ordered graphitic carbon bonds [26]. The ratio between D and G bands (ID∕IG) is often used to evaluate the degree of carbon graphitization. For the CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres, the ratio was 0.96, and this suggests a high degree of graphitization in the carbon coating of the Fe3O4 microspheres. This graphitization is beneficial for electrical conductivity of the composite [27].

The nitrogen absorption/desorption isotherms of CP-Fe3O4@C show a hysteresis from 0.5 to 1.0 relative pressure (see Figure 2c). The BET surface area of the CP-Fe3O4@C was equal to 16.8 m2⋅g−1. The pore size distribution curve shows a peak near 3.8 nm (see insert in Figure 2c), evincing a nanopore presence. High surface area and porosity provide good contact between the electrode material and the electrolyte. This in turn promotes Li+ diffusion and allows active material to adapt to the volume expansion [28].

The XPS of CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres shows peaks corresponding to Fe, C and O (see Figure 2d). High-resolution scans and curve fitting show Fe peaks at 711.2 and 724.8 eV, which belong to Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2, respectively (see Figure 2e), which are typical of Fe3O4-based materials [29, 30]. Two pairs of peaks at 710.3 and 723.3 eV and at 711.9 and 725.5 eV correspond to Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 of Fe2+ and Fe3+, respectively [31]. High-resolution scans of C 1s (see Figure 2f) show peaks at 284.4 (typical of sp2-hybridized graphitic C), 285.0 eV (attributed to the sp3-hybridized C) and at 286.3 and 289.0 eV (both of which are attributed to the carbon layer surface functional groups such as C =O and O =C =O) [32].

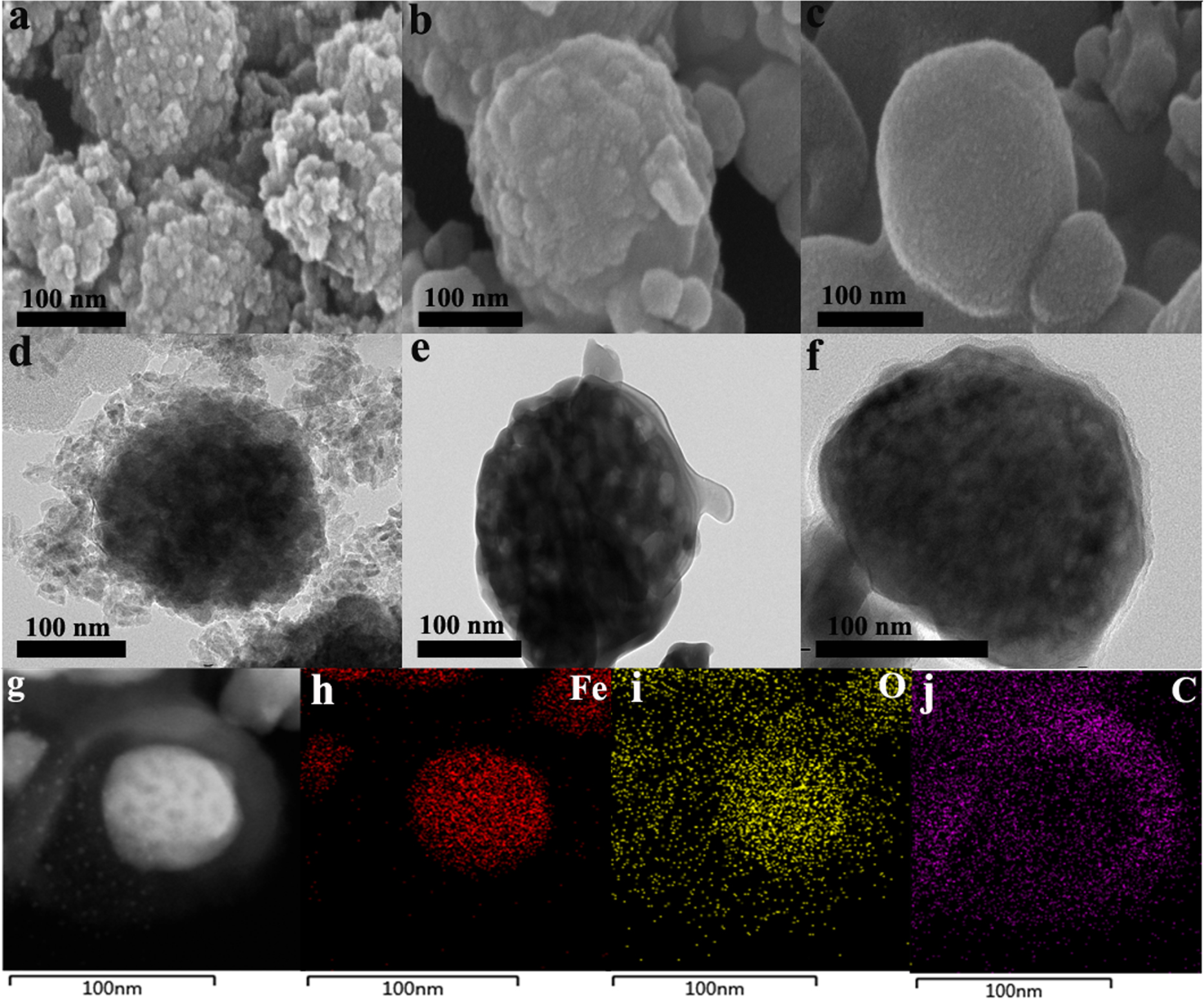

The SEM of Fe3O4@GU microspheres demonstrated particles with uniform spherical shapes with an average diameter of 250 nm (see Figure 3a). After annealing, Fe3O4@GU microspheres were completely converted to Fe2O3 microspheres (Figure 3b) as supported by XRD. The surface of the Fe2O3 microspheres shows strong porosity unlike Fe3O4@GU microspheres. Micrographs of the CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres obtained after carbon coating of Fe2O3 microspheres are shown in Figure 3c. It can be seen that the surfaces of the CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres are smooth compared to those of the Fe2O3 microspheres because the carbon layer was successfully coated. Figures 3d, e and f are TEM images of Fe3O4@GU, Fe2O3 and CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres, respectively. From these three figures, it can be seen that both Fe2O3 and CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres show clear porosity, while Fe3O4@GU microspheres exhibit almost none. The TEM image of the CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres shows a thin carbon outer layer approximately 20 nm thick (see Supplementary Figure S2). High-resolution TEM images of the CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres (Supplementary Figure S3) show distinct lattice fringes with a spacing of 0.252 nm, which corresponds to the (311) planes of cubic Fe3O4. The scanning TEM image of the CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres (Figure 3g) and the corresponding element mapping (Figure 3h–j) further establish that CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres were successfully carbon-coated.

SEM images of (a) Fe3O4@GU, (b) Fe2O3 and (c) CP-Fe3O4@C composites. TEM images of (d) Fe3O4@GU, (e) Fe2O3 and (f) CP-Fe3O4@C composites. EDX elemental mapping of (g–j) CP-Fe3O4@C composite.

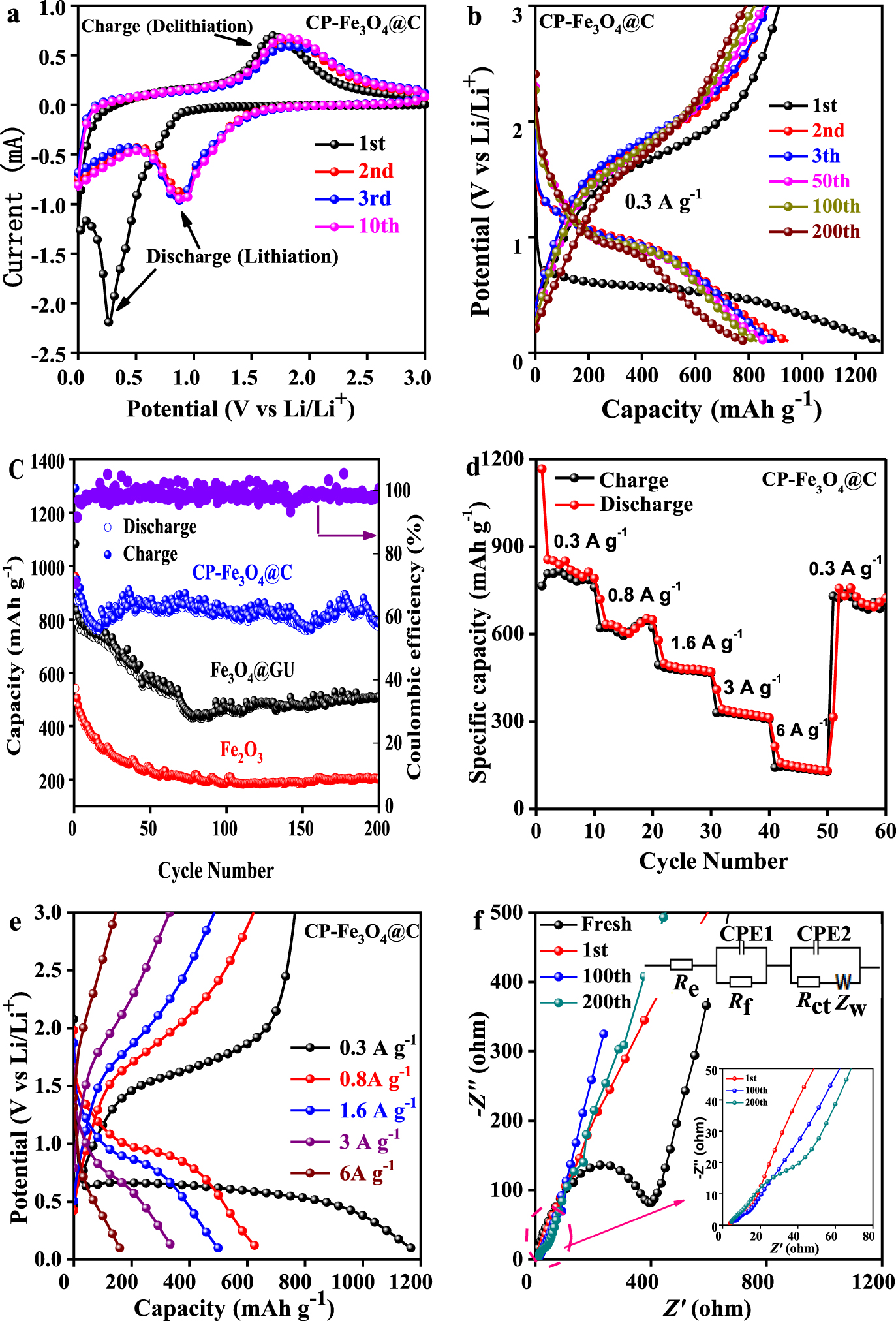

Cyclic voltammetry of the CP-Fe3O4@C electrode displays a definite reduction peak at 0.2–0.8 V during the first discharge (Figure 4a), which corresponds to the structural transformation caused by lithium incorporation according to the chemical reaction:

(a) CV curves at 0.1 mV⋅s−1 and (b) GCD curves at 0.3 A⋅g−1 of the CP-Fe3O4@C electrode. (c) Cyclic performance at 0.3 A⋅g−1 of the Fe2O3, Fe3O4@GU and CP-Fe3O4@C electrodes. (d) Rate performance at different current densities. (e) Representative discharge–charge voltage profiles at various rates. (f) Nyquist plots of the CP-Fe3O4@C electrode (top right insets show the equivalent circuit model).

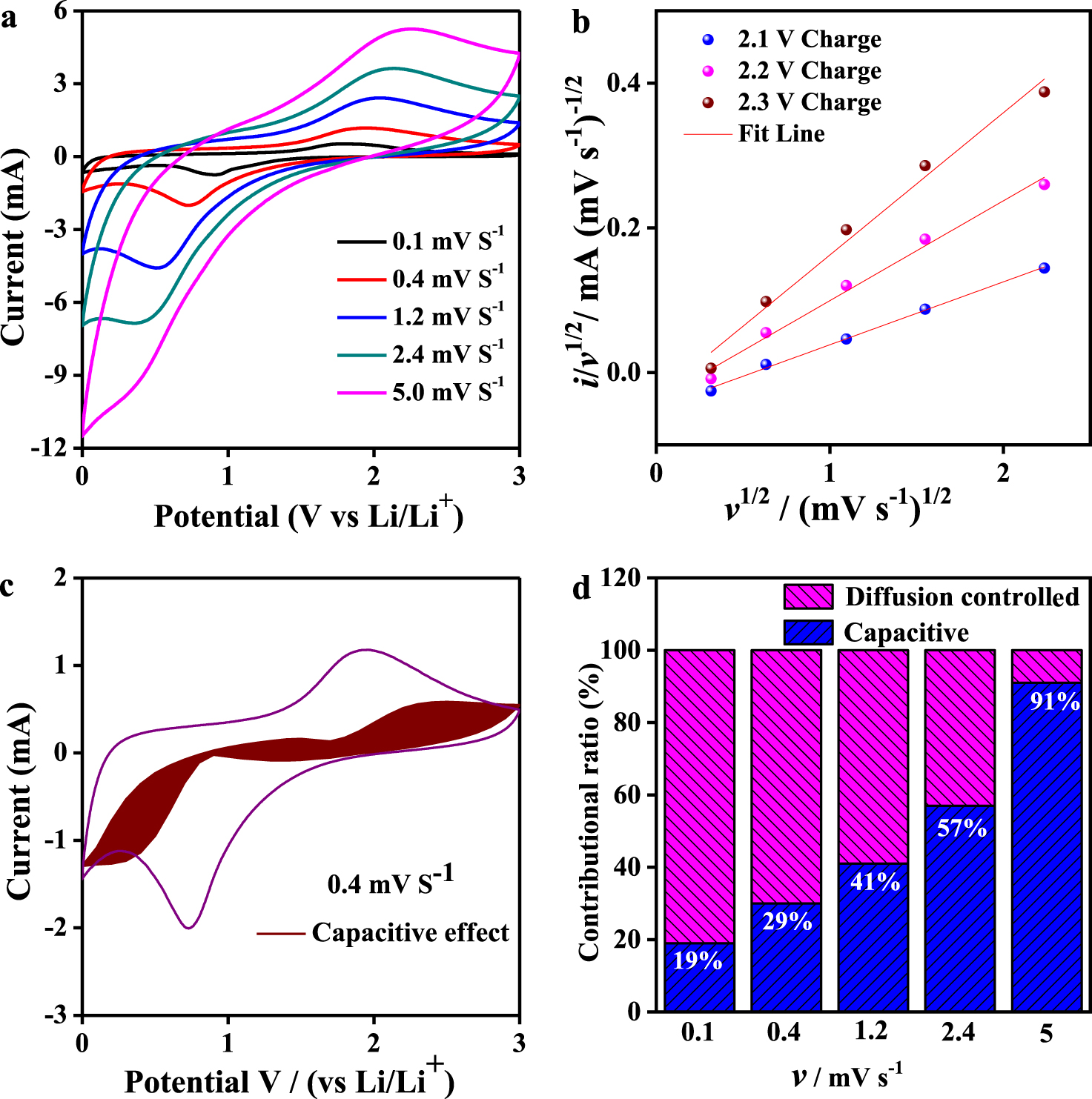

(a) CV curves at different scan rates from 0.1 to 5 mV⋅s−1. (b) The fitted lines of i(V )∕v1∕2 versus i∕v1∕2 at different voltages. (c) CV curves with capacitive contribution at 0.4 mV⋅s−1. (d) Separation of contributions from capacitive effects and diffusion-controlled capacities at different scan rates.

The electrochemical impedance behavior of the CP-Fe3O4@C electrode under different current cycles at the same current density was studied using Nyquist plots (see Figure 4f). All plots exhibit semicircles in the high- and intermediate-frequency regions and oblique curves at low frequencies. Additionally, equivalent circuit modeling (top right insets, Figure 4f) was carried out using Z-VIEW software to obtain kinetic parameters of three composites. According to the equivalent circuit diagram, the intercept of the high-frequency semicircle with the x-axis corresponds to the electrolyte resistance (Re), while Rf and Rct correspond to SEI film and charge transfer resistances, respectively [27, 34]. The slope at low frequencies corresponds to the Warburg impedance (Zw) of the Li+ diffusion; CPE1 and CPE2 are the SEI film and double layer capacitances, respectively [35, 36]. CP-Fe3O4@C-based anodes exhibited lower Rct values (which were equal to 16.5 Ω) after the first cycle, especially when compared to Rct values of the fresh cycle (which was equal to 395.7 Ω). This difference is mainly due to the wetting of the electrode and proper SEI formation during the first cycle. The Rct value after the 200th cycle differs only slightly from the Rct value after the 100th cycle, again pointing to an excellent electrode structural stability. Resistance values of electrodes based on Fe3O4@GU and Fe2O3 active materials were higher than the total resistance of the CP-Fe3O4@C-based electrodes for all cycles tested in this work (see Supplementary Figures S4a and S4b).

The rate performance of CP-Fe3O4@C-based LIB anodes as well as their reaction kinetics was analyzed by CV. The contribution of capacitance is calculated and identified using gradually increasing sweep rates during CV as shown in Figure 5a. Using the method of Dunn [37, 38], the total current response (i) at constant potential (V ) can be represented as a combination of surface capacitive effects and diffusion-controlled insertion processes (see (1) and (2)):

| (1) |

| (2) |

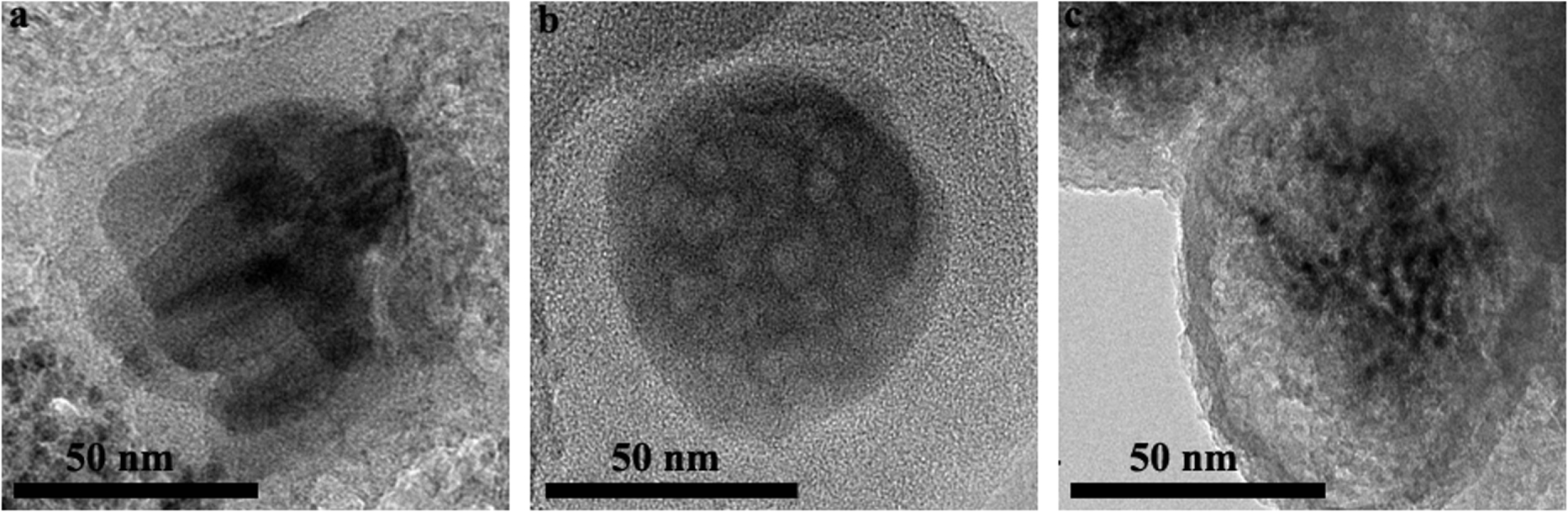

CP-Fe3O4@C electrode: (a) before cycle, (b) after 10 cycles and (c) after 60 cycles.

The morphology of the CP-Fe3O4@C-based electrode was tested before cycling and also after 10 and 60 cycles (Figure 6). Fe3O4 microspheres in prepared CP-Fe3O4@C electrode material are uniformly wrapped by a carbon layer (see Figure 6a). The carbon coating on the CP-Fe3O4@C electrode after the 10th cycle is still intact, and the carbon layer is mostly unchanged (see Figure 6b). After the 60th cycle, Fe3O4 structurally deteriorates into smaller microspheres, but Fe3O4 remains well coated with carbon layers (see Figure 6c).

4. Conclusions

In summary, the core–shell CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres were synthesized by simple methods using common inexpensive and easily removable chemicals as filler particles. The unique structural characteristics of the CP-Fe3O4@C microspheres yielded electrodes with capacities equal to 785 mAh⋅g−1 (at 0.3 A⋅g−1 after 200 cycles). In addition, it was further shown that the CP-Fe3O4@C electrode has excellent rate performance through reaction kinetics. These experimental results show that the CP-Fe3O4@C composite prepared by this simple method has strong prospects as an active anode material for high-performance LIBs.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Future Scientists Program of “Double First Class” of China University of Mining and Technology (No. 2019WLKXJ025).

Supplementary data

Supporting information for this article is available on the journal’s website under https://doi.org/10.5802/crchim.18 or from the author.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier