1. Introduction

Charged polymer chains, also referred to as “polyelectrolytes” (PEs), are omnipresent among natural compounds (e.g., polysaccharides, nucleic acids) or indeed among the many synthetic substances used in food, cosmetic, and packaging industries as well as in water treatment and several other fields [1]. The behaviour of charged polymer chains in solution, and we shall restrict ourselves here to aqueous solutions, is a world of its own. Two possible reference situations can be thought of as systems of departure: (a) electrolyte solutions and (b) uncharged polymer chains in solution. In the first case, we depart from a solution of atomic or molecular ions, both positive and negative, and we add connectivity between one type of these ions, be it positive or negative. This creates significant charge density inhomogeneities in the solution. This is by now not the common way of thinking about PE solutions, but it was indeed the point of departure for Fuoss et al. back in the 1950s [2]. In the second case, we start with the already quite complex case of a macromolecular chain in solution, where the quality of the solvent (good/theta/bad) decides the chain conformation. Next we add charge to a fraction of the monomers on the chain, but importantly we also need to introduce a population of counterions into the surrounding solution (and partially condensed onto the chain if the necessary conditions are met). Either way, the transition (adding connectivity or adding charge) is far from trivial and the consequences in terms of the structure, interactions, and dynamics of the (macro)molecular species present in such a solution are considerable. This is naturally reflected in the very different properties of the solution at the macroscopic scale, its phase diagram, rheology, osmotic pressure, heat of dilution, and other thermodynamic properties [1].

Historically, it is indeed through the macroscopic properties that the peculiar behaviour of PE solutions was uncovered, and the rheological studies of Fuoss et al. (the Fuoss law) remain a reference in this respect (e.g., [3]). Tremendous progress has been made since the Fuoss studies and we recommend two reviews, dating from very different times, to trace this progress [4, 5]. A breakthrough came in the 1970s with the advent of scattering techniques, in particular neutron scattering, the seminal experimental work of Cotton, Jannink et al. [6, 7], and the accompanying theoretical developments by de Gennes, Pfeuty et al. (the scaling approach) [8, 9, 10]. From this point onwards, the molecular level description of solutions of neutral polymers and later on PE solutions indeed began to emerge.

Overall, the scaling-based theory of PE solutions is highly successful, especially when dealing with the interpretation of neutron and X-ray scattering experiments. There, it predicts correctly the scaling of the PE chain correlations probed via the universally observed maximum in the scattering data, the so-called polyelectrolyte peak. This feature of the scattering curves is completely absent for solutions of neutral polymers and reflects the electrostatic repulsion present in solutions of charged chains. De Gennes’ theory of PE solutions was later broadened by Dobrynin and Rubinstein to include all cases of solvent quality and concentration regimes [11]. The initial picture of dilute and semidilute concentration regimes was enriched (entangled and nonentangled subregimes) and extended, especially in the high concentration range [12, 13, 14]. The competition between electrostatic repulsion along a PE chain and hydrophobic (solvophobic) collapse has led to the prediction of the so-called pearl-necklace conformation of PE chains for the case of bad solvent [15], and these have indeed been observed experimentally [16, 17] and by simulations [18].

Both the conformation of individual chains (the chain form factor) and the chain–chain correlations (the structure factor) modify the scattering curves. These individual contributions often cannot be distinguished easily, contrary to solutions of inorganic colloids for example. Polymer/PE solutions pose two problems in this respect: (1) the conformation of polymer/PE chains changes as a function of concentration and (2) polymer chains are penetrable objects, that is, individual chains can get entangled. A very elegant method, the zero average contrast (ZAC) method, is accessible in neutron scattering to highlight each of the contributions for cases where deuteration of the polymer/PE chains is possible [19]. In the absence of such measurements, the main feature to account for in the scattering spectra remains the position of the scattering peak. As follows from the above paragraphs, the position of the PE peak depends not only on the PE concentration but also on the chain conformation (consequence of the effective chain charge and the solvent quality).

In our past publications, we have shown that for identical PE concentration, solvent quality, and valence of the counterions, the chemical nature of the counterion by itself can also influence the shape of the scattering curve, the position, and shape of PE peak and the extent to which this peak is indeed visible or not [20, 21]. The origin lies in the hydration of the given ion, which leads to a different degree of screening of the chain charge. When the chemical nature of an ion is to “blame” for a given observation, biochemists and physical chemists refer to such instances as ion-specific effects [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. It has been observed that ion-specific effects manifest themselves more strongly for anions than cations [28, 29]. Solutions and gels based on cationic chains with compensating anions, such as ionenes [20, 21, 30], show indeed stronger ion-specific effects than anionic PEs, such as the widely studied polystyrene sulfonate [31, 32, 16, 33, 34]. Needless to say, any purely electrostatic theory, such as the scaling approach of de Gennes, the Manning theory of counterion condensation [35, 36], or indeed the Poisson–Boltzmann approach [32] cannot account for these effects as hydration properties of solvated ions do not come into consideration. Attempts in what seems the correct direction are theories accounting for local dielectric heterogeneities around the ions and the PE chains [37]. The orientation of the dipole moment of water molecules is indeed closely linked to the hydration and the polarisability of the hydrated species.

Ionenes, the focus of this study, are a group of water soluble cationic PEs with pH independent charge, based on quaternary ammonium charged centers linked by simple hydrocarbon chains. Ionenes have already several applications including ion exchange resins [38], water treatment in the oil industry [39], humidity sensors [40], organic templates in the synthesis of mesoporous silica [41], and anti-microbial agents [42]. Within the realm of PEs, ionenes present the advantage of a regular and tunable separation of charges on the backbone, as opposed to statistically distributed charges for other PEs. In our initial scattering studies on ionene aqueous solutions, we explored the transition from hydrophilic to hydrophobic polyelectolyte behaviour as the ionene charge density decreases. This transition was indeed found, however later than expected: the hydrophobicity of the hydrocarbon backbone of ionenes becomes “visible” when only 15% of the monomers are charged, not before [21]. Dramatic ion-specific effects in ionene aqueous solutions have been initially observed in thermodynamic properties [43, 44, 45] and later on the microscale by scattering for the particular case of two halide ions, F− and Br− [20, 21]. In this contribution, we show how this generalises for an entire series of halide counterions and what consequences it has for the dynamics of the PE chains. We bring information on the chain dynamics at the microscopic (nm) scale, by the neutron spin echo (NSE) technique, and also on the mesoscopic (μm) scale, by pulsed field gradient NMR (PFG-NMR).

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Ionenes: synthesis and structural overview

Ionenes and their precursors were synthesised using a procedure adapted from those described previously [20, 45, 21]. The details of the synthesis are provided in the SI file (part 1). The synthetic route leads invariably to ionenes with bromide counterions. The molecular weights of ionenes were determined by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) as described in [46]. The range of molecular weights is 20,000–60,000 g/mol, which corresponds to 100–300 nm in terms of chain length. SEC measurements on cationic PEs are very difficult [47] and, for us, were successful only for 6,9-ionenes. In the following, we consider that the above range of molecular weights applies also to ionenes of other charge densities, which were synthesised under identical conditions. We have indeed confirmation that the molecular weights of ionenes with different charge densities are of the same order of magnitude from the NMR signal of amine end groups, which allows estimation of the degree of ionene polymerisation [48].

Counterion exchange was performed by dialysis starting from Br-ionenes. Dialysis tubes (Sigma-Aldrich, MWCO = 12,000 g⋅mol−1) were filled with 0.02 M solutions of Br-ionenes and first dialysed against 0.05 M solution of the desired NaX (3 weeks) to exchange anions and then dialysed against water (2 weeks) to remove sodium ions. All ionene solutions for neutron scattering and NMR measurements were prepared gravimetrically. Deuterated water (Eurisotop, 99.9%D) was used for neutron scattering samples as well as NMR samples. The pH of the solutions was close to neutral, and thus we estimate the effects of any dissolved carbonic acid as very small.

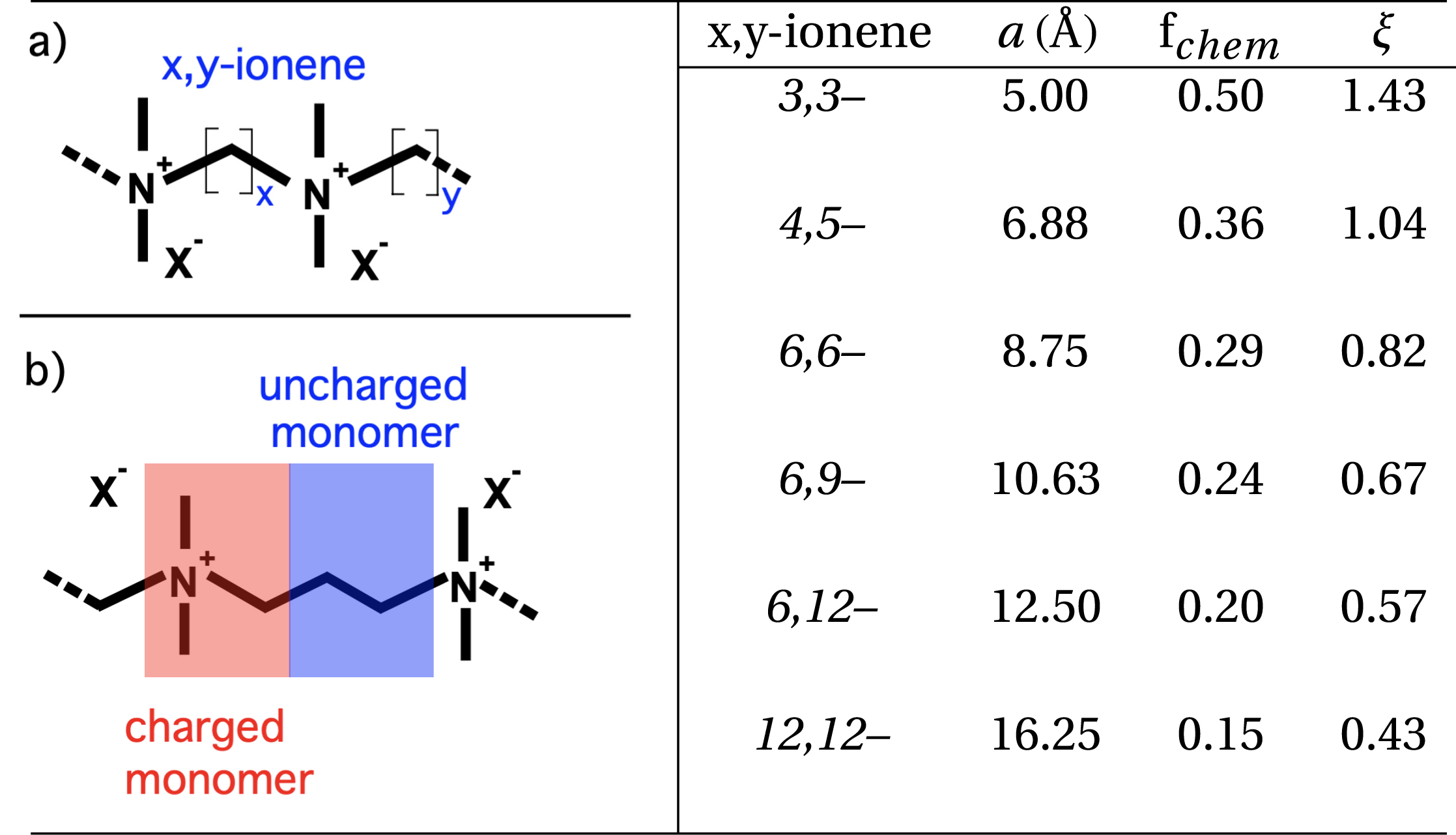

The general chemical formula of ionenes is [–(CH3)2N+–(CH2)x–(CH3)2N+–(CH2)y–]n for an x,y-ionene chain with Br− or other counterions (Figure 1). Ionenes with X− counterions are referred to as X-ionenes in the rest of the manuscript. Values x and y represent the number of –CH2– (methylene) units between adjacent charged centers (quaternary ammonium centers) and can be varied accurately by synthesis [49, 50, 51]. By increasing x and y, the ionene chain is less charged. In this manuscript, we discuss ionene chains for which x, y = 3,3 and 6,9 (referred to as 3,3-ionenes and 6,9-ionenes). The simple structure (absence of bulky side groups) and finely tunable and regular charge density are very interesting structural features of ionenes. Other PEs, including styrene, often present charge on (bulky) side groups and charged monomers are distributed statistically along the chains. In order to draw a parallel between ionenes on one side and polystyrene-based and other PEs on the other side, we may consider the structure of ionenes as a sequence of charged and uncharged “monomers” as depicted in Figure 1.

Left: (a) Schematic view of an x,y-ionene chain. (b) Schematic view of a 3,3-ionene (x = 3, y = 3) chain, showing the definition of a charged and an uncharged monomer. Right: Ionene structural parameters: a is the charge separation on the chain, fchem the fraction of charged monomers, and 𝜉 the Manning charge density parameter, defined as 𝜉 = LB/a, where LB is the Bjerrum length (7.14 Å in water at room temperature). While 4,5-ionenes are at the 𝜉 = 1 limit (onset of Manning-type condensation), only 3,3-ionenes have sufficient charge density to induce significant condensation (𝜉 > 1) and decrease the chemical charge (fchem) to an effective charge (feff).

2.2. Neutron scattering

Small angle neutron scattering (SANS) measurements were carried out on the PACE spectrometer at LLB-Orphée, Saclay, France. Using up to three different combinations of incident neutron wavelength (𝜆) and sample to detector distance, a wavevector (q) range of 0.01–0.45 Å−1 was covered (q = 4πsin(𝜃/2)/𝜆). The detector efficiency was taken into account by normalisation of data with a flat (incoherent) signal from bulk light water. Ionene solutions (hydrogenated chains in D2O solvent) were loaded into quartz cells with a path length of 1 or 2 mm. Due to the isotropic nature of our samples, data were grouped in concentric rings, each corresponding to a given q value. The measured scattered intensities were corrected for transmission, sample thickness, and incoherent and solvent background to yield the coherent scattered intensity Icoh. We checked the reproducibility of neutron scattering spectra by measuring samples from different synthesis batches.

Neutron Spin Echo (NSE) [52, 53] experiments were carried out on the IN15 spectrometer in ILL, Grenoble, France. Samples (hydrogenated chains in D2O solvent) were measured in 1 mm or 2 mm flat quartz cells. Using a combination of two neutron wavelengths, 6 Å and 9 Å, and detector angles of 3°, 5°, 7°, 10°, 13°, 19° at 6 Å and 3°, 6° at 9 Å, we achieved an accessible q range of 0.04 Å−1 to 0.5 Å−1 and time range of 0.07–11 ns at 6 Å and 0.25–36 ns at 9 Å. Both static (Icoh) and dynamic data (I(q,t)) in NSE were corrected for contributions from the quartz cell and the solvent (D2O) background.

2.3. Pulsed field gradient NMR

The single pulse 1H NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker Avance III 300 MHz NB spectrometer operating at 7.05 T. The lock was obtained with a sealed 2 mm capillary filled with D2O inserted inside the NMR tube. The chemical shift was referenced to CHCl3. The PFG_NMR experiments were performed using a BBFO probe equipped with a 55 G⋅cm−1 gradient coil. We used an NMR pulse sequence combining bipolar gradient pulses and stimulated echo. This sequence was repeated with 16 gradients of increasing strength from 2 to 50 G⋅cm−1 for a duration of 1.5 ms. The diffusion time was approximately 200 ms, which corresponds to a diffusion over a length scale of 1.5 μm. The self-diffusion coefficients are obtained by nonlinear least-square fitting of the echo attenuation, using the Bruker TopSpin software. All PFG-NMR data were measured at room temperature on ionene solutions in D2O.

3. Results and discussion

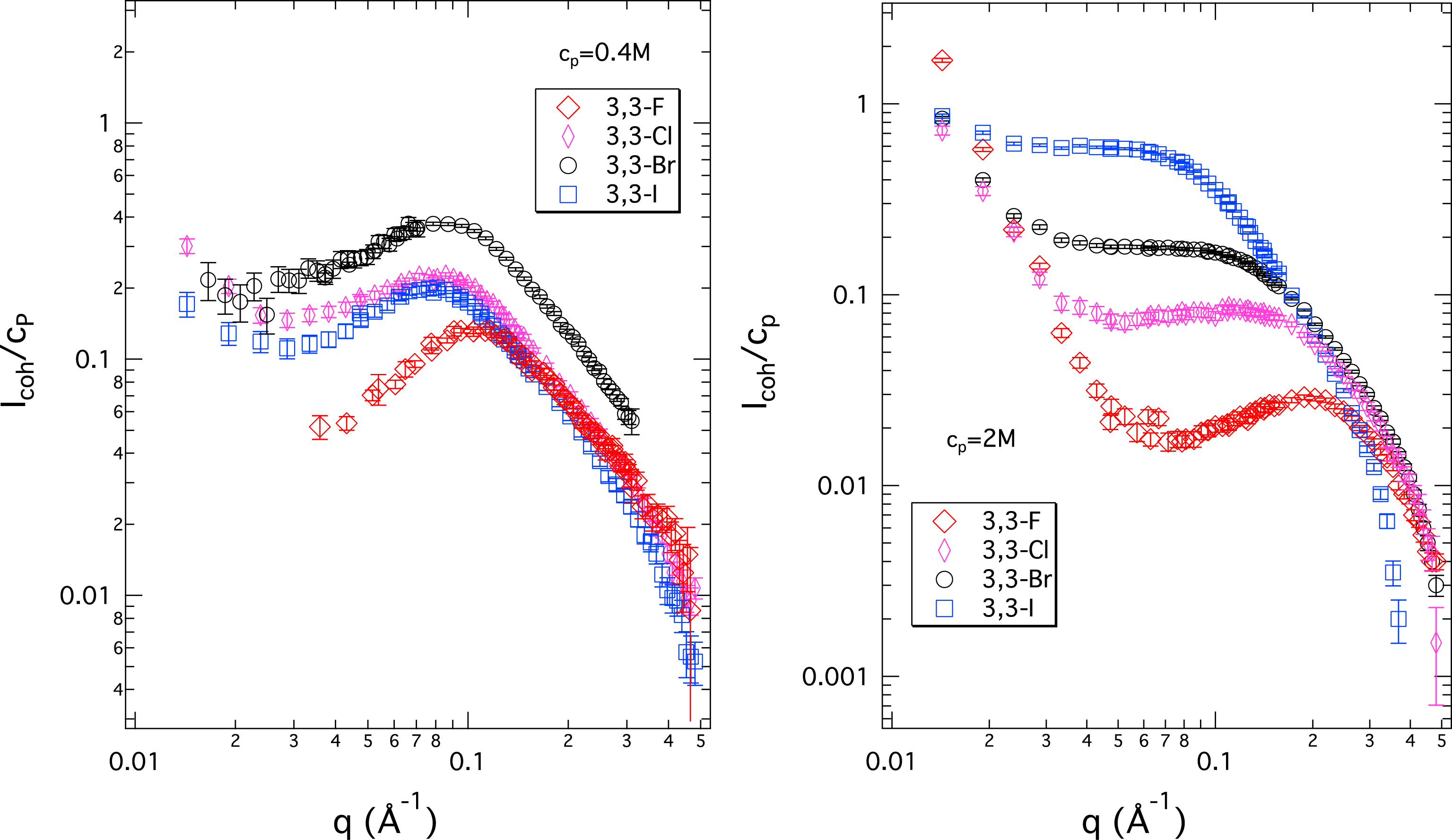

SANS data of 3,3 X-ionenes with four different halide counterions (X− = F−, Cl−, Br−, I−), at a moderate and a high monomer concentration, are shown in Figure 2. From our previous scattering studies on ionenes, we know that both of these concentrations are in the semidilute regime. The overlap concentration for ionenes synthesised using our protocols was estimated to be below cp = 0.07 M [20]. In addition, viscosity data (see SI part 2) confirms that both F-ionenes and Br-ionenes are in the same concentration regime, that is, semidiluted. In the semidiluted regime, the position of the peak reflects the mesh size formed by the interpenetrating chains. At 0.4 M monomer concentration, the spectra of all systems show a well-defined PE peak (a clear maximum) at an almost identical position in the wavevector q (a slight shift towards higher q values is noticed for the F-ionene; see later). At high monomer concentration (2 M), the four systems feature very different scattering curves. Note that the increase in intensity in the small q region (q < 0.03 Å−1) is due to large-scale heterogeneities in the system—a repeatedly observed feature for PE solutions/gels, which remains poorly understood. The changes that interest us most are thus confined to the q region roughly between 0.03 Å−1 and 0.4 Å−1. In this central region, a clear PE peak remains visible only for the F-ionene. Its position is shifted to higher q values in comparison to data at 0.4 M, as expected, due to a denser mesh size at this higher concentration. In the sequence F− → Cl− → Br− → I−, the central part of the spectrum gains in intensity and the intensity dip to the left of the PE peak seen for F-ionene gradually disappears. As a consequence, the peak becomes highly asymmetric (in the case of Cl-ionene, still a slight maximum is observed). The peak disappears completely for the Br-ionenes and I-ionenes and instead a plateau is seen in the spectra, resembling a signal we would expect from a neutral polymer.

Coherent neutron scattering intensity normalised by ionene monomer concentration (Icoh/cp) in arbitrary units versus scattering wavevector (q) for room temperature aqueous solutions (in D2O) of 3,3 X-ionenes at two monomer concentrations, 0.4 M (left) and 2 M (right). These monomer concentrations correspond to volume fractions around 2% and 10%, respectively.

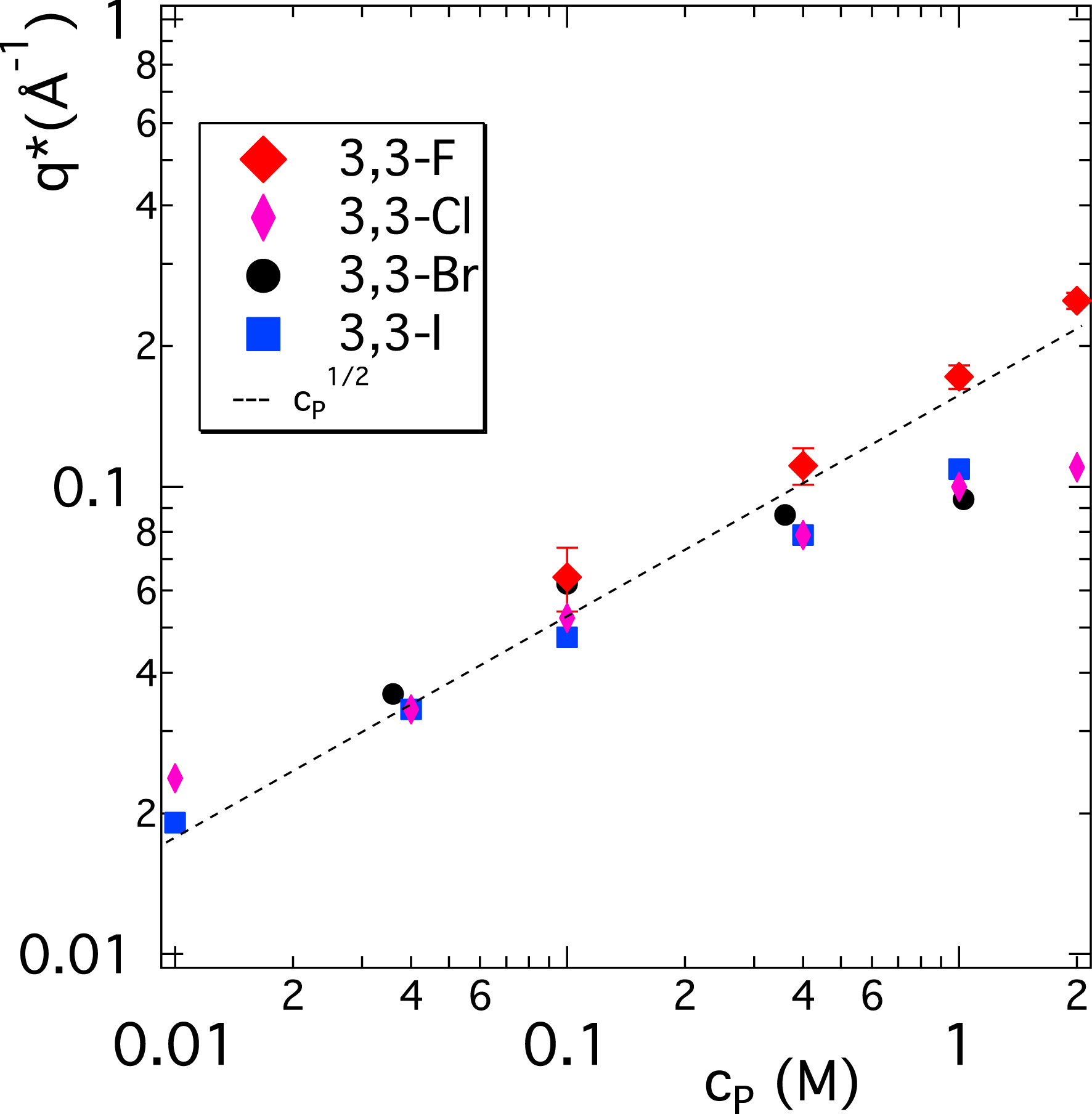

Figure 3 summarises the position of the PE peak for the four 3,3 X-ionenes seen in their SANS spectra. Up to 0.1 M concentration, the position of the peak is very close for all systems; for cp > 0.1 M, the situation changes. Only the F-ionene follows the predicted law and the three other systems depart significantly from this description. Combining information from Figures 2 and 3, we observe that at 0.4 M, the PE peak position for 3,3 F-ionene is already somewhat higher than for all other systems; all curves present a well-defined PE peak. For higher concentrations, the strong departure from the law in Figure 3 for Cl-, Br-, and I-ionenes is mainly a consequence of the PE peak disappearing from the scattering signal. For a poorly defined asymmetric peak, the determination of its position is increasingly difficult (see the right side of Figure 2). Overall, clearly the ion-specific effect is a high concentration phenomenon and we can place the critical concentration at around 0.1 M. This corresponds to a charge concentration in the system of 0.05 M according to c(X−) = c(N+) = cpfchem.

Position of the polyelectrolyte peak in SANS spectra (q∗) versus ionene monomer concentration (cp) for 3,3-ionenes with different counterions. Typical error bars are represented on the 3,3-F data set. Dashed line is a guide to the eye representing a scaling law, expected in the semidilute concentration regime.

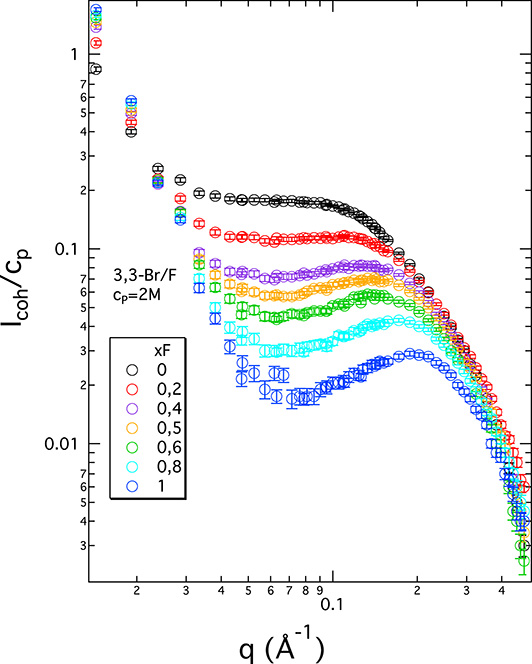

In order to further investigate the ion-specific effect and its consequence on the scattering spectra, we carried out measurements for a series of ionenes with mixed counterion clouds at a constant monomer concentration. This was done for ionenes of different charge densities (3,3, 6,9, and 12,12). (Note that based on our previous scattering results, we know that only the 12,12-ionenes begin to show the signature of backbone hydrophobicity [21]. All ionene chains with higher charge densities behave as hydrophilic.) The most striking changes in the spectra are observed for the most highly charged chains (3,3-ionenes), and this system is shown in Figure 4. Additional data for 6,9-Br/F and 12,12-Br/F systems are included in the SI file (part 3). The two extreme systems (xF = 1 and xF = 0) are naturally identical to the F- and Br-ionene data in Figure 2. All intermediate systems place themselves logically between the two extremes, with gradual changes with increasing/decreasing xF. The complete disappearance of the PE peak (absence of a maximum) is only present for the pure Br system. As expected, the intermediate curves cannot be obtained by a linear combination of the curves corresponding to the xF = 1 and xF = 0 extremes [54]. For a given xF, each chain is surrounded by a mixed counterion cloud at the given ratio; there are no chains in a “pure F” or “pure Br” environment. Interestingly, as we decrease the charge density of the ionene chains (6,9- and 12,12-ionenes), the difference in scattered intensity between the pure F and pure Br extremes is diminished (see SI). This is probably due to a decreasing overall counterion concentration in the system as we move from 3,3- to 12,12-ionenes.

Coherent neutron scattering intensity normalised by ionene monomer concentration (Icoh/cp) in arbitrary units versus scattering wavevector (q) for room temperature aqueous solutions (in D2O) of 3,3-ionenes with mixed Br–F counterion clouds. The fraction of F− counterions (xF) is shown in the legend. All systems are at 2 M monomer concentration.

Having scattering data for ionene solutions across a whole series of halide counterions gives a very strong argument for the previously suggested origin in terms of a decreased effective charge of the ionene chains as we move towards larger, more polarisable ions with a lower hydration energy, that is, as we descend the halogen series in the periodic table. For completeness, radii of halide ions in solution, polarisability, and hydration energies are summarised for the four halide ions used in Table 1. For the larger ions, the counterion atmosphere around the ionene backbone is more constricted as has also been clearly shown by previous molecular dynamics simulations on ionene solutions [55]. As soon as counterion clouds of adjacent chains do not overlap, the repulsion between the chains is no longer present and the PE peak in the scattering spectra disappears. This is a concentration-dependent phenomenon, accentuated at high PE (and thus counterion) concentration, which we can refer to as “ion-specific screening”. It seems important to distinguish this from counterion condensation in the Manning sense of the word. As we have seen by osmotic pressure measurements in ionene solutions in the past [20] and as was equally observed for other systems [56], the counterions indeed still contribute to the osmotic pressure. This is contrary to what has been seen for counterions in solutions of hydrophobic polystyrene-based PEs, where counterions are condensed as part of the “pearls” in the pearl-necklace conformation [57].

Ionic radii in solution (Rs), polarisabilities (𝛼), and hydration free energies (ΔGhyd) for halide ions

| Ion | Rs [58] (Å) | 𝛼 [59] (Å3) | ΔGhyd [59] (kcal/mol) | ΔGhyd (kBT/ion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F− | 1.24 | 1.20 | −112.1 | −189.3 |

| Cl− | 1.80 | 3.65 | −82.4 | −139.1 |

| Br− | 1.98 | 4.96 | −76.1 | −128.5 |

| I− | 2.25 | 7.30 | −67.0 | −113.1 |

For completeness, we note that the interpretation of the SANS on ionene solutions, here and in our previous publications [20, 21], is based on the assumption that the scattered signal is dominated by the ionene monomer–monomer correlations and that contributions of the counterions can be neglected. The underlying estimation of the relative intensities is provided in the SI (part 4). It shows that contributions of halide ions to the scattered intensity increase as we move from F− to I−. Importantly, for the purposes of the qualitative trends that we discuss here, and which are common to ionenes of all charge densities, the above assumption is indeed reasonable.

In the following, we are interested in exploring the rigidity of the ionene chains as a function of the above ion-specific screening. We have explored this for the case of F− and Br− counterions using the NSE technique [52, 53]. Neutron spin echo gives access to the microscopic dynamics of the chain on the length scale of nm and a timescale of ps-ns. These are sufficiently short length scales to avoid the influence of large heterogeneities, which lead to the observation of a slow mode, a very common feature in dynamic light scattering studies on PE solutions [60, 61]. The measured data in NSE is the intermediate scattering function I(q,t), which is formally the spatial Fourier transform of the van Hove correlation function g(r,t). We measure the dynamic data on the coherently scattered signal arising from the contrast between hydrogenated ionene chains in a deuterated solvent (D2O), the same systems as those used previously for the small angle scattering experiments. The NSE data were collected for ionene chains with intermediate chain charge densities, 6,9-ionenes, at 0.4 M and 2 M monomer concentrations.

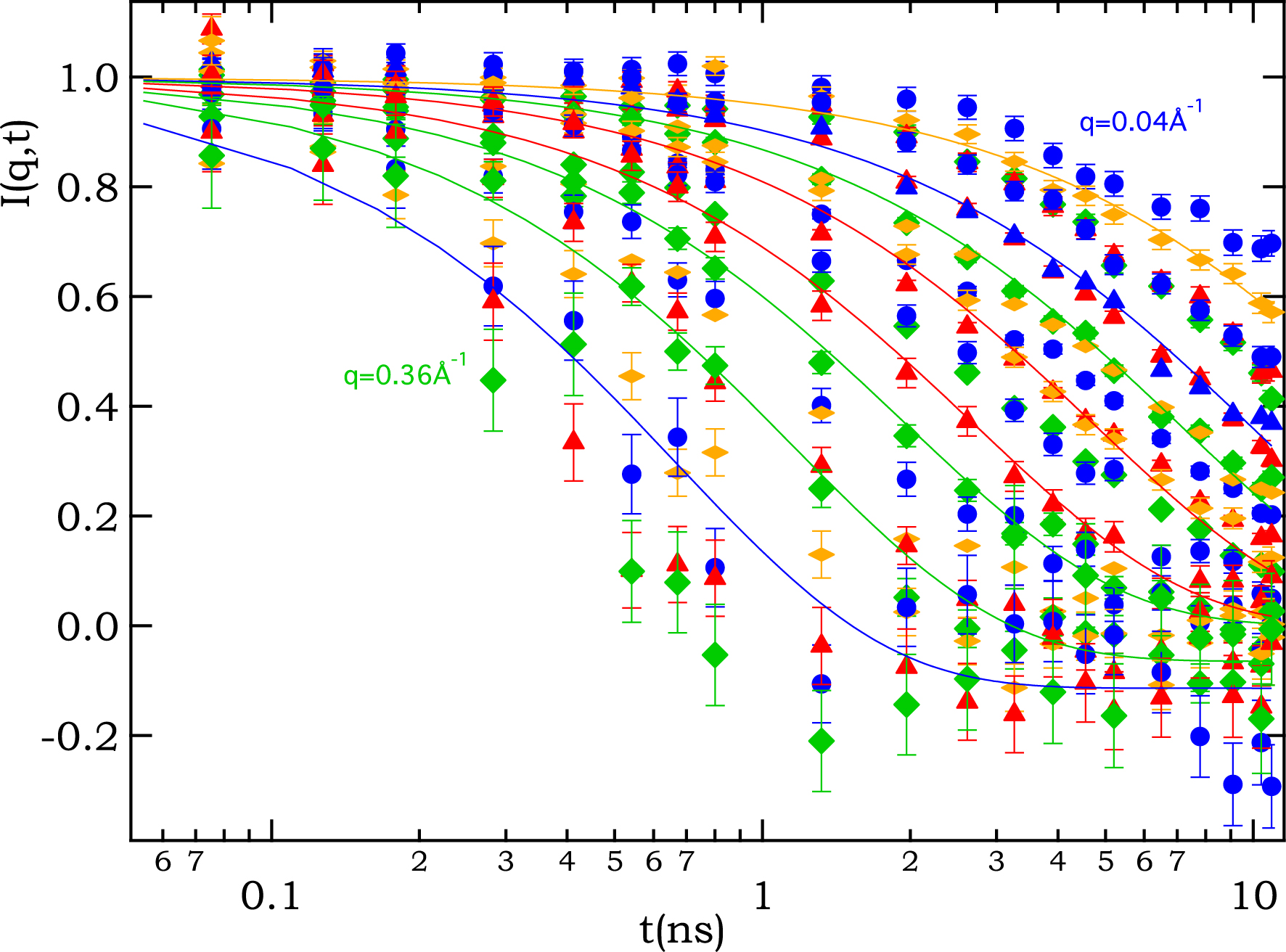

An example of NSE data is shown in Figure 5, where a series of I(q,t) curves for 6,9-Br ionene at 0.4 M is presented, each curve corresponding to a given q value. Following a standard analysis, the data was modeled using mono-exponential decay to obtain a value of a characteristic relaxation time 𝜏 at a given q value. Under a simple diffusion model, this characteristic time is converted into an effective diffusion coefficient Deff following the relation 1/𝜏 = Deff q2. Note that for large q values, the background corrections (quartz cell and solvent) lead to an unphysical long-time asymptote of slightly less than 0. For these cases, the fitting parameters were relaxed to allow for a nonzero (slightly negative) constant background.

Intermediate scattering function I(q,t) for 6,9-Br ionene at cp = 0.4 M as measured by NSE. Each curve corresponds to a given q value in the range from 0.04 to 0.36 Å−1. Lines are mono-exponential fits for a selection of the curves.

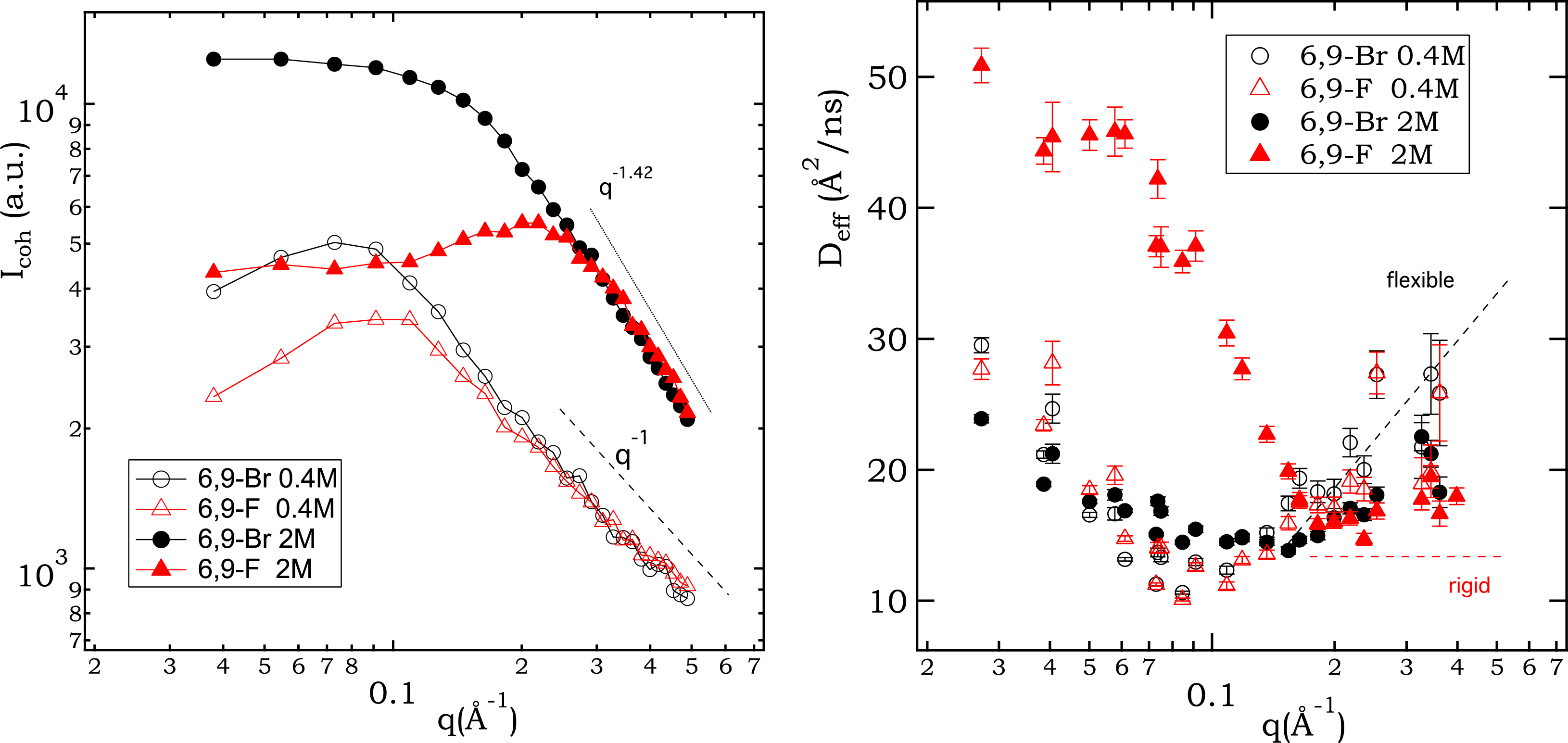

Figure 6 summarises the coherently scattered intensity (as measured by polarisation analysis on NSE) and the effective diffusion coefficients Deff resulting from the mono-exponential fitting of the I(q,t) curves. Data for all four systems studied by NSE are shown: 6,9-Br and 6,9-F ionenes, each at 0.4 M and 2 M monomer concentration. The position of the PE peak in the coherently scattered intensity observed by NSE (Figure 6, left) reflects what has been observed already by SANS (Figures 2 and 4). The data for Br- and F-ionenes at low monomer concentration show a peak at the same q position while at high concentration, the scattered intensity is radically different. For completeness, the relative contributions of coherent and incoherent scattering, as determined by polarisation analysis in NSE, are presented in SI (part 5).

Coherently scattered intensity (polarisation analysis in NSE, left) and effective diffusion coefficient Deff (right) as a function of the wavevector q for all systems studied by NSE. Note that 10 Å2/ns = 10−10 m2/s.

In Figure 6 (left), we also indicate the high q intensity dependence. Assuming that the chain–chain correlations do not contribute in a significant way to the scattered intensity in the high q region (this is an approximation, as we are not working under the “zero average contrast” conditions here), the power law reflects the conformation of the individual chains. While a q−1 behaviour is characteristic of a rod-like conformation (and this is the case of the low concentration data for both Br- and F-ionenes), a q−2 behaviour corresponds to the signal of a Gaussian chain, in other words a neutral polymer in a Θ solvent (q−1.7 indicates Gaussian chains with an excluded volume contribution). It is clear that compared to 0.4 M data, both 2 M data sets have a higher decay exponent (q−1.42) at high q values, which indicates a less rod-like conformation. At the same time, we need to note that the high q dependence in the SANS spectra (Figures 2 and 4) does not agree with the NSE-determined decay exponents. The SANS data features much higher exponents (close to q−2 already for the 0.4 M data sets and even higher for the 2 M data sets). It is important to realise that the decay exponent at high q is very sensitive to the incoherent background subtraction. This is done in very different ways in SANS and in NSE. In SANS data reduction, the density of H atoms is first estimated from the concentrations of the hydrogenated chains in the deuterated solvent and compared to H atom density of pure water. The background constant to subtract is determined from the ratio of these two H atom densities. In NSE, the decomposition of the total scattered signal into coherent and incoherent contributions is measured directly using polarisation analysis, which relies on the spin flip of incoherently scattered intensity from H nuclei [62]. As a result, we consider the high q exponents determined from NSE as more reliable and we do not conclude on the chain conformation from the high q SANS signal.

There are several points to note regarding the effective diffusion coefficients in Figure 6 (right), all of the order of 10−10 m2/s. We may consider the figure in two parts, below and above the q∗ position or the high q end of the observed plateau, depending on the given system. Both theory [63] and previous experiments [64, 65, 66] on PE solutions show a rapid decrease in Deff for q < q∗ and then a constant value for q > q∗. The constant value at high q reflects the rod-like conformation of a charged chain. On the contrary, the signal in a semidilute solution of a neutral polymer chain should show Deff increasing linearly with q in the high q region [67]. The behaviour of Deff in the case of charged rigid chains stems from the theoretical considerations of de Gennes and collaborators [63]. First, Deff is expressed as Deff = kBT𝜇(q)/S(q), where 𝜇(q) is the mobility and S(q) is the static scattering signal [68]. This is indeed a mathematical expression of the so-called “de Gennes narrowing”, which in a simplified way states that a slowing down of dynamics takes place in q regions where peaks in structural correlations are present. Clever modelling by de Gennes indicates that for locally rigid chains, 𝜇 = 𝜇(0)/(qlp), where lp is the persistence length, that is, 𝜇 ∝ q−1 for qlp⩾1. Taking into account that for locally rigid chains S(q) ∝ q−1 in that same high q range, the q dependence of Deff cancels out and a constant Deff in the high q region is recovered.

From the high q behaviour, the most rigid chain is indeed that of F-ionenes at 2 M concentration, as this data set features the most constant values beyond q∗. The remaining three systems (Br 2 M, Br 0.4 M, and F 0.4 M) all feature a more significant increase in Deff beyond q∗. Although both 0.4 M data sets exhibited clear rod-like behaviour in the coherently scattered intensity (Figure 6, left), these chains do not show the highest rigidity as seen from Deff. One difficulty in the interpretation is probably the intra- and inter-chain correlations mixing in both the static and dynamic signals. Measurements under ZAC would probably help disentangle the inter- and intra-chain correlations contributing to the scattered signal, at least for the static signal. NSE measurements under ZAC seem challenging.

Overall, we view the trends in Figure 6 (right) as consistent with the theoretical predictions outlined previously, which indicate above all a very different rigidity for the ionene chains with Br− and F− ions at 2 M concentration. The striking difference between Br and F is related to the very different scattered intensities: as q decreases below 0.2 Å−1 (a) the 2 M F system passes through a structural maximum and its dynamics increases very fast for all smaller q values; (b) the scattered intensity for the 2 M Br system continues to grow below 0.2 Å−1 to reach a plateau, and the dynamics in 2 M Br is significantly suppressed in comparison to 2 M F in the entire region below 0.2 Å−1, but begins to rise slowly once the plateau is reached.

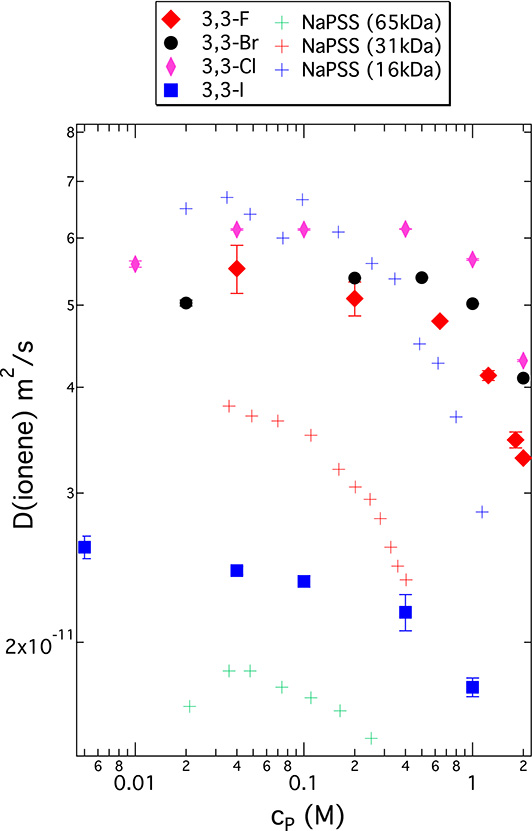

The mesoscopic dynamics of ionene chains in D2O solutions was measured by PFG-NMR. Figure 7 summarises the DNMR data for 3,3-ionenes with the four different halide counterions as a function of monomer concentration cp. For comparison, this figure also features data from sodium polystyrene sulfonate (PSS), measured by PFG-NMR in H2O, from reference [69]. The ionene and PSS data fall into the same range of DNMR of the order of 10−11 m2/s. At room temperature, the ratio of D2O and H2O viscosities is 1.25, and this conversion factor would have to be used for a detailed quantitative comparison of the two data sets. The ionene chains correspond to molecular weights of 20–60 kDa, which fall well within the range of molecular weights for the PSS data [69]. However, the size polydispersity (PID) of ionene chains (due to the poly-addition reaction as opposed to radical polymerisation for PSS) is significantly higher: PID(ionene) = 1.8–2.0 and PID(PSS) = 1.25–1.5. Given these differences, we do not dwell on a detailed quantitative PSS–ionene comparison. The general trend as a function of cp is similar for the two types of PE chains, with a decrease in DNMR for cp above approximately 0.1–0.2 M.

Self-diffusion coefficients of ionene chains for 3,3-ionenes with four different halide counterions as indicated versus monomer concentration cp (solvent = D2O) as measured by PFG-NMR. Crosses correspond to measurements for polystyrene sulfonate with Na+ counterions (NaPSS) at three different molecular masses as indicated. NaPSS data from reference [69] (solvent = H2O).

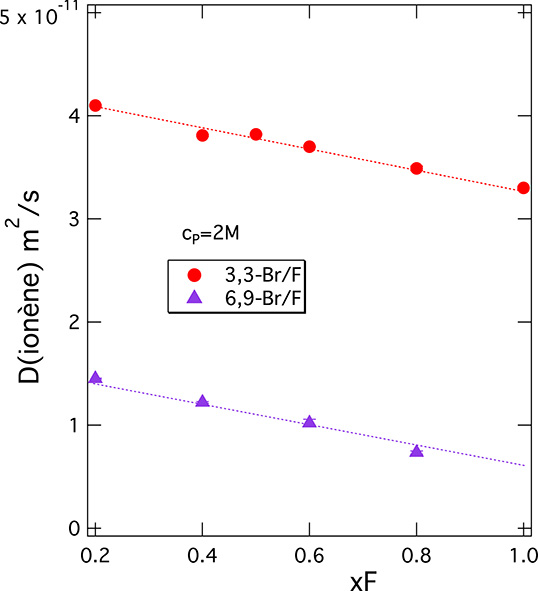

Let us concentrate on the DNMR data in Figure 7 for different counterions, especially in the higher cp region (above 0.1 M). The ordering of DNMR data for 3,3-ionenes does not follow in a simple way the halide anion series, contrary to what was seen in the SANS data. The order here is D(F) < D(Cl) > D(Br) ≫ D(I). We see two phenomena behind this non-monotonous behaviour: (a) change in chain conformation (less rod-like as we move down the halide series towards larger anions) and (b) inter-chain aggregation (the system becomes less soluble as we move down the halide series). A change from rod-like to globular chain conformation leads to an increase in self-diffusion coefficient of the chain [70]; the inter-chain aggregation leads to its decrease (diffusion of larger objects). For the 3,3 I-ionenes, the inter-chain aggregation is indeed pronounced; 3,3 I-ionene shows a significantly lower DNMR than all the other systems (roughly lower by a factor of 2) throughout the entire concentration range. This scenario is consistent with the evolution of viscosity (𝜂) of aqueous solutions of a neighbouring cationic PE, poly(diallyldimethylammonium), along the halide series [71]. Indeed, 𝜂 decreases between Cl− and Br− solutions of this PE (chains change from a rod-like to a more globular conformation), and the system becomes insoluble with I− (no F− data are available in ref [71]). We attach importance to the fact that 3,3 F-ionenes show somewhat lower DNMR than Br- and Cl-ionenes in the moderate to high cp range. To ensure that this difference is real, we have explored changes in DNMR for ionenes with mixed Br/F counterion clouds. The data is summarised in Figure 8 for two different ionene charge densities. Indeed, as we move from pure Br to pure F ionene chains, the chain dynamics clearly decreases.

Self-diffusion coefficients of ionene chains for systems with mixed Br/F counterion atmospheres at a monomer concentration of 2 M as a function of F− counterion fraction xF as measured by PFG-NMR. Two different ionene chain charge densities are presented.

4. Conclusion

The combination of SANS, NSE, and PFG-NMR provides us with several pieces of information on the state of the counterion atmosphere around positively charged PE chains in aqueous solution as a function of the counterion chemical nature, that is, ion-specific effects. A series of monovalent halide counterions is explored. A strong ion-specific effect is observed clearly at high PE monomer concentrations and is consistent with the picture of an increasingly more compact counterion atmosphere around the PE chain, a phenomenon we refer to as “ion-specific screening”. A stronger counterion screening of the charge on the PE chains takes place as we move along the halide series towards larger, more polarisable and more weakly hydrated counterions. This can indeed be seen as another example of the Collins’ concept of “matching water affinities” in which ions are characterised by their “softness” with consequences for favourable ion pairing between “soft” (weakly hydrated) anions and cations on one hand and “hard” (strongly hydrated) anions and cations on the other [26]. Within the Collins’ classification, the quaternary ammonium groups on ionene PE chains are “soft” cations, and thus more favourable ion-paring is in place with “soft” halide ions, that is, larger and more polarisable anions. More effective screening of the PE chain charge is demonstrated by a reduced chain–chain repulsion in the system as shown by the disappearance of the PE structural peak in the scattering data. Importantly, the ion-specific effect has consequences for the chain rigidity and local and mesoscopic chain dynamics as shown further by NSE and PFG-NMR.

In principle, it is important to distinguish between the self-diffusion coefficient measured by PFG-NMR (due to the position encoding method using magnetic field gradients, PFG-NMR indeed measures self-diffusion) at the μm scale and the effective diffusion coefficient Deff of the PE chains as measured by NSE (arising from the coherently scattered signal) at the nm scale. Depending on the length scale (q value), Deff obtained by NSE indeed represents different quantities: (a) for length scales below the mesh size (q values above q∗), it represents the local individual chain dynamics [63]; (b) for length scales above the mesh size (q values below q∗), Deff merges with Dcollective in the hydrodynamic limit q→0, (e.g., [72]). Let us now look at the different scales in turn, starting from the most local scale:

- Local scale below PE mesh size, probed by NSE: Here, the notion of collective motion seen via the coherent signal in NSE no longer applies; the scale probed is too small. NSE probes the dynamics of individual chains and informs us on their rigidity. We observe that PE chains retaining a strong chain–chain repulsion (i.e., with F− counterions) show increased rigidity of the PE chains at high monomer concentration.

- nm scale larger than the PE mesh size, probed by NSE: Here, NSE dynamic data probe collective dynamics in the PE network, as the coherent signal is dominated by the inter-chain correlations at these length scales. For locally rigid chains (i.e., with F− counterions), the collective dynamics at this scale is very fast. For more flexible chains (i.e., with Br− or Cl− counterions), the dynamics here is suppressed. We see this as a case of “de Gennes narrowing”, as the Br− and Cl− systems show an intense scattering signal at this spatial scale. The effective collective diffusion coefficients at the nm scale are all of the order of 10−10 m2/s.

- μm scale, probed by PFG-NMR: On this largest scale, PFG-NMR probes the self-diffusion of the individual PE chains. Locally rigid charged chains, with fast collective dynamics seen at the nm scale (i.e., with F− counterions), diffuse consistently slightly slower than locally more flexible chains with slow nm scale dynamics. The self-diffusion coefficients at the μm scale are all of the order of 10−11 m2/s.

Dynamics in PE solutions has been probed extensively by DLS [60]. In the semidilute PE concentration regime, this techniques gives access to the collective dynamics (Dcoll) at the mesoscopic scale; the closest length scale would be the PFG-NMR scale. Concentrating on the fast mode in the DLS signal, charged rigid PE chains show consistently faster collective dynamics compared to flexible neutral chains. This is again a demonstration of de Gennes narrowing, which leads to large values of Dcoll for repulsive systems at length scales much larger than the PE mesh size (expressed in the scattering language, as q < q∗, which is where DLS operates). For charged chains at high monomer concentration in the absence of salt, the order of magnitude for DLS-determined collective diffusion coefficients is 10−10 m2/s [60]. This is the same order of magnitude as the collective diffusion coefficients measured here by NSE. Furthermore, the order of magnitude difference between self-diffusion and collective diffusion coefficients in PE solutions has been noted before (Dself≪Dcoll) [60, 69]. Our new data sets (NSE, PFG-NMR) on ionene PE solutions are consistent with these observations. However, the effects of the counterion specificity on Dself measured here by PFG-NMR suggest that Dself of charged chains is lower than that of neutral chains. In other words, the loss of charge on the chain, due to counterion-specific screening of the chain charge, has the opposite effect on Dself and Dcoll. This seems to be indeed in line with very recent DLS and PFG-NMR data on PSS [73]. Overall, the more strongly charged chains adopt a more extended conformation, resulting in a lower self-diffusion coefficient while the collective diffusion in these more repulsive systems is enhanced (de Gennes narrowing).

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organisation that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organisations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sašo Čebašek at the University of Ljubljana for help with sample preparation, Matija Tomšič at the University of Ljubljana for help throughout NSE measurements at the ILL (Grenoble), and François Ribot at the College de France (Paris) for discussions and access to NMR spectrometers. The NSE data from ILL is available under doi:10.5291/ILL-DATA.9-11-1624.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0