1 Introduction

Geomagnetic field strength is of considerable interest in our understanding of the physical processes in the Earth liquid core that generate the field. The spatial and temporal variations in the Earth's magnetic field can provide powerful constraints on the mechanism of the geodynamo. Glatzmaier et al. [12] and Coe et al. [10] recently suggested that the absolute intensity should be a fundamental constraint in numerical models that promise to provide unprecedented insight into the operation of the geodynamo. However, the most recent analyses of available absolute paleointensity results [35] show that, there are about 10 acceptable quality determinations per million years between 5 and 10 Ma and less than 2 determinations per Myr between 10 and 160 Ma. There is now general agreement among the whole paleomagnetic community that reliable paleointensity data are still scarce and cannot yet be used to document the general characteristics of the Earth's magnetic field.

Juarez and Tauxe [21], based on the study of submarine basaltic glass (SBG), argued that the geomagnetic field strength was substantially lower than the value of approximately 8×1022 A m2 often quoted for last 5 Myr [13]. However, the excellent technical quality of paleointensity data obtained from basaltic glasses, first underlined by Pick and Tauxe [32], is not by itself a proof of the geomagnetic validity of the paleostrength found [14]. Moreover, as recently showed by Heller et al. [20], SBG contains a grain-growth chemical remanent magnetization in magnetite. Consequently, more reliable data from continental volcanic rocks carrying thermoremanent magnetization are required for last 5 Myr.

In this paper we present Thellier paleointensity results obtained in some of the Baja California Peninsula lava flows erupted during Early Pliocene time. The previous detailed paleomagnetic study [29] of these volcanics was particularly encouraging. Thus, we already had some crucial information about the samples suitability for Thellier paleointensity experiments.

2 Sampling details

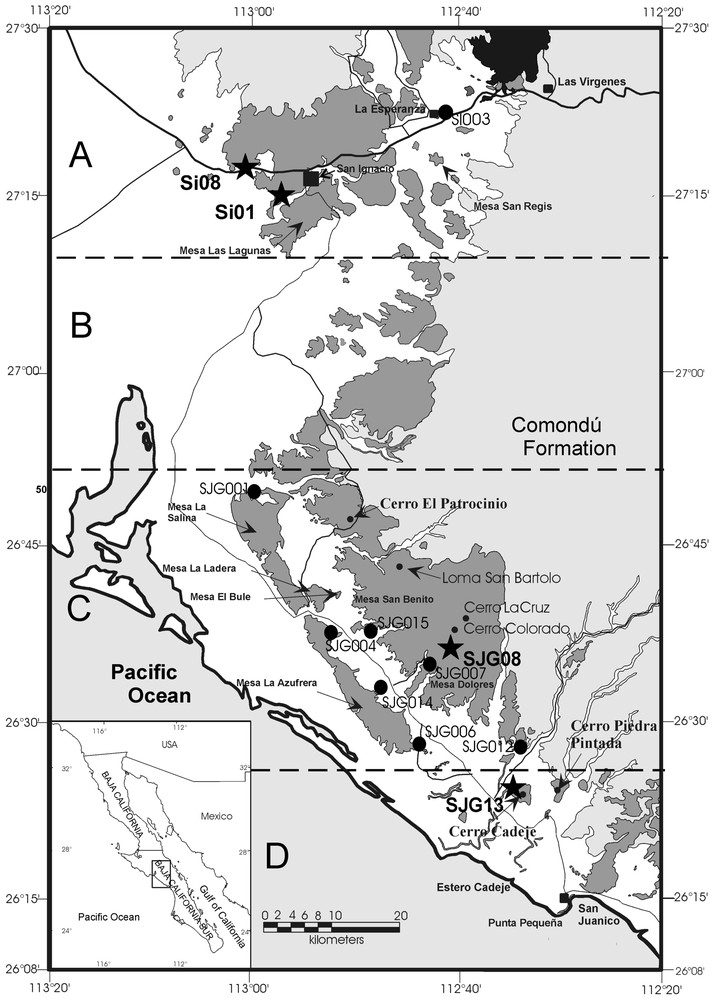

Vast areas of the northern and central parts of Baja California Sur are covered by Cenozoic volcanic rocks (Fig. 1), which were studied by several authors (e.g. [5,11,18,19]). It was believed for a long time that volcanism at this area was due to the opening of the Gulf of California, but Cañón-Tapia et al. [5,6] showed that intra-continental volcanism also seems to be involved; this type of volcanism occurred between the transition from the end of oceanic plate subduction at the West and the opening of the Gulf at the East.

Map of the area of study showing location of the Pliocene sites used to determine absolute paleointensities. The shaded area shows the extent of the present-day lava cover on the region that includes tholeiitic and alkaline lavas.

Carte de la zone étudiée montrant la localisation des sites pliocènes utilisés pour déterminer les paléointensités absolues. La partie ombrée montre l'étendue de la couverture de laves actuelles comportant des laves tholéiitiques et alcalines.

Negrete-Aranda and Cañon-Tapia [29] recently carried out a systematic paleomagnetic sampling at sites located in Mio-Pliocene lava flows in the area located between 27°30′N and 26°08′N latitude and between 112°20′W and 113°20′W longitude (Fig. 1). From their large collection (more than 300 standard paleomagnetic cores), we selected sites (Early Pliocene) with the best magnetic behavior for paleointensity determination. Isotopic ages obtained by Gastil et al. [11], Sawlan and Smith [38] and Aguillón-Robles et al. [1] on the alkaline volcanism in the vicinity of San Ignacio Town indicate that this type of product [37], including the lava flows studied here, were commonly erupted around 3 Ma, whereas the tholeiitic lavas are commonly much older, ca. 9–11 Ma. Although some exceptions to this rule can be found [36], in the absence of a more extensive data set, the age of the lava flows can be approximated by these intervals, by paying attention to the lava composition and to the relative stratigraphic position whenever possible.

3 Sample selection

The selection of samples for paleointensity measurements was made according to the following magnetic experiments and observations:

- – Viscosity index measurements [33]: selected samples yield short term viscosity indexes all lower than 5%. These values are small enough to make precise remanence measurements with regular spinner magnetometer;

- – Thermal demagnetization of samples: selected samples carry mainly single (stable) magnetization components [29]. Minor secondary components were occasionally observed but can be easily removed in the very first steps of demagnetization;

- – Low-field susceptibility measurements with temperature show the presence of a single ferrimagnetic phase with Curie point compatible with Ti-poor titanomagnetite (Fig. 2A). The microscopic observations (under reflected light) on polished sections show that the main magnetic mineral is low-Ti titanomagnetite associated with exsoluted ilmenite (Fig. 2B, C) probably formed as a result of oxidation of titanomagnetite during the initial flow cooling. These intergrowths typically develop at temperatures higher than 600 °C [17] and consequently, the natural remanent magnetization carried by these samples should be a thermoremanent magnetization.

(A) Susceptibility versus temperature curves of representative samples selected for Thellier paleointensity experiments. (B) Representative reflected light microphotograph of studied basalts, oil immersion, crossed nicols. (C) Examples of ilmenite intergrowth of the ‘trellis’ type in titanomagnetite transformed into Ti-poor titanomagnetite.

(A) Courbes de susceptibilité en fonction de la température d'échantillons représentatifs, sélectionnés pour les expériences de paléointensité de Thellier. (B) Microphotographie représentative, en lumière réfléchie, des basaltes étudiés en immersion dans l'huile, avec nicols croisés. (C) Exemples de croissance de type « treillis» d'ilménite dans une titanomagnétite transformée en titanomagnétite pauvre en titane.

In total only 46 samples providing the above described magnetic characteristics were selected for the Thellier paleointensity experiments [43].

4 Paleointensity measurements

The remanent magnetization was measured with JR-5a and JR-6 (AGICO LtD) spinner magnetometers (sensitivity ∼10−9 A m2) at either the paleomagnetic laboratory of CICESE or the National University of Mexico (UNAM). Paleointensity experiments were performed using the Thellier method [43] in its modified form [9]. The heatings and coolings were made in vacuum (using a MDT80 paleointensity oven) and the laboratory field set to 30, or sometimes 20 microteslas. Ten temperature steps were distributed between room temperature and 560 °C. The control heatings (so-called pTRM checks) were performed 5 times throughout whole experiments (Fig. 3).

The representative NRM–TRM plots (so-called Arai-Nagata plots) and associated orthogonal vector diagrams from Pliocene Baja California samples. In the orthogonal diagrams the numbers refer to temperatures in °C. o – projections into the horizontal plane, x – projections into the vertical plane.

Points représentatifs NRM–TRM (appelés points Arai-Nagata) et diagrammes vectoriels orthogonaux associés, pour les échantillons pliocènes de la Baie de Californie. Dans les diagrammes orthogonaux, les nombres représentent les températures en °C. o – projections dans le plan horizontal, x – projections dans le plan vertical.

Paleointensity data are reported on the classical Arai-Nagata [28] plot on Fig. 3 and results are given in Table 1.

Paleodirectional and Paleointensity results from Baja California Pliocene volcanic rocks

Résultats sur les paléodirections et la paléointensité, obtenus sur les roches volcaniques pliocènes de la Baie de Californie

| Site | Dec | Inc | α 95 | k | Sample | N | Tmin–Tmax | f | g | q | FE±σ(FE) | VDM | VDME |

| SI_1 | 174.6 | −26.8 | 3.5 | 171 | SI1_1B | 9 | 300–560 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 13.3 | 21.5±1.1 | 5.12 | 5.1±0.5 |

| SI1_3A | 7 | 350–540 | 0.52 | 0.79 | 6.5 | 21.3±1.4 | 5.07 | ||||||

| SI1_5B | 7 | 350–540 | 0.56 | 0.76 | 8.2 | 18.3±0.9 | 4.36 | ||||||

| SI1_7A | 8 | 300–540 | 0.55 | 0.82 | 8.9 | 22.9±1.4 | 5.45 | ||||||

| SI1_9B | 7 | 350–540 | 0.53 | 0.80 | 5.0 | 24.0±2.1 | 5.71 | ||||||

| SI_8 | 349.4 | 28.1 | 3.8 | 160 | SI8_83 | 8 | 300–540 | 0.63 | 0.84 | 11.9 | 13.1±0.6 | 3.09 | 3.6±0.5 |

| SI8_82 | 7 | 300–520 | 0.55 | 0.81 | 6.2 | 15.1±1.1 | 3.57 | ||||||

| SI8_85 | 7 | 250–500 | 0.52 | 0.80 | 7.7 | 17.4±1.0 | 4.11 | ||||||

| SI8_87 | 9 | 300–560 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 16.7 | 17.5±0.5 | 4.13 | ||||||

| SI8_89 | 6 | 300–500 | 0.38 | 0.77 | 5.3 | 13.9±1.0 | 3.28 | ||||||

| SJG_8 | 357.6 | 48.9 | 2.0 | 451 | SJG8_87T | 6 | 350–520 | 0.45 | 0.76 | 4.8 | 34.1±2.3 | 6.68 | |

| SJG_13 | 20.6 | 49.9 | 2.2 | 321 | SJG13_126A | 6 | 350–520 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 8.5 | 26.9±1.2 | 5.21 | 6.2±1.1 |

| SJG13_128C | 6 | 350–520 | 0.49 | 0.75 | 4.9 | 36.7±3.0 | 7.11 | ||||||

| SJG13_129C | 8 | 300–540 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 7.8 | 31.8±2.5 | 6.16 | ||||||

| SJG13_130B | 7 | 350–540 | 0.63 | 0.78 | 6.5 | 30.4±2.8 | 5.89 | ||||||

| SJG13_131A | 7 | 350–540 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 4.6 | 33.6±3.6 | 6.51 | ||||||

| SJG13_133A | 7 | 350–540 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 13.3 | 41.4±1.7 | 8.02 | ||||||

| SJG13_136B | 7 | 350–540 | 0.62 | 0.78 | 6.6 | 23.9±1.8 | 4.63 | ||||||

| SJG13_137C | 7 | 350–540 | 0.44 | 0.77 | 8.6 | 29.7±1.2 | 5.78 |

We accepted only determinations that satisfied all of the following requirements:

- – Obtained from at least 6 NRM–TRM points corresponding to a NRM fraction larger than about 1/3 [9];

- – Yielding quality factor q [9] of about 5 or more;

- – Positive pTRM checks (at least two): we define pTRM checks as positive if the repeat pTRM value agrees with the first measurement within 10%. Because the small (low-temperature) pTRMs are hard to measure precisely on the background of the full NRM/TRM, we must allow some larger deviation of pTRM checks (within 15%);

- – The directions of NRM end points at each step obtained from paleointensity experiments are stable and linear pointing to the origin. No significant deviation of NRM remaining directions towards the direction of applied laboratory field was observed. Additionally, we calculated the ratio of potential CRM(T) to the magnitude of NRM(T) for each double heating step in the direction of the laboratory field during heating at T [13]. The values of angle γ (the angle between the direction on characteristic remanent magnetization (ChRM) obtained during the demagnetization in zero field and that of composite magnetization (equal to NRM(T) if CRM(T) is zero) obtained from the orthogonal plots derived from the Thellier paleointensity experiments) are all <10° which attest that no significant CRM was acquitted during the laboratory heatings.

5 Discussion and main results

We consider the characteristic paleomagnetic directions determined to be of primary origin. This is supported by the occurrence of antipodal normal and reversed polarities [29]. In addition, thermomagnetic investigations show that the remanence is carried in most cases by Ti-poor titanomagnetite, resulting from oxi-exsolution of the original titanomagnetite during the initial flow cooling, which most probably indicates the thermoremanent origin of a primary magnetization. Moreover, unblocking temperature spectra and relatively high coercivity point to ‘small’ pseudo-single domain magnetic structure grains as responsible for the remanent magnetization. Single-component, linear demagnetization plots were observed in most cases. All studied sites are horizontal or sub-horizontal and, thus, no tectonic corrections were applied to the mean directions.

19 reliable absolute intensity results have been obtained from southern Baja California volcanics. The major weakness of the present study may reside in the amount of data to document the field intensity during Pliocene and Early/Middle Pleistocene times. However, if one turns to the most detailed analyses of worldwide paleointensity data it appears that there are about 5 acceptable quality determinations per million years between 0.3 and 10 Ma and less than 1 determination per Myr between 10 and 400 Ma [30,42], IAGA paleoinetnsity database (so-called Montpellier paleointensity database, ftp://ftp.dstu.univ-montp2.fr/pub/paleointb) maintained by Mireille Perrin and Elisabeth Schnepp [31]. There is now a general agreement among whole paleomagnetic community that reliable paleointensity data are still scarce and cannot be yet used to document the general characteristics of the Earth's magnetic field. In this context, 19 high quality individual determinations (from four independent cooling units) should be welcomed.

Although our results are not numerous, some credits should be given because of good technical quality determination, attested by the reasonably high quality factors. The NRM fractions used for paleointensity determination range from 38 to 79% and the quality factors varies between 4.8 and 16.7, being normally greater than 5. The Thellier method [43] of paleointensity determination, which is considered the most reliable one [13,27], imposes many restrictions on the choice of samples that can be used for a successful determination [23–25,32,34]. The almost 95% failure rate that we find in our study is not exceptional for a Thellier paleointensity study, if correct pre-selection of suitable samples and strict analysis of the obtained data are made.

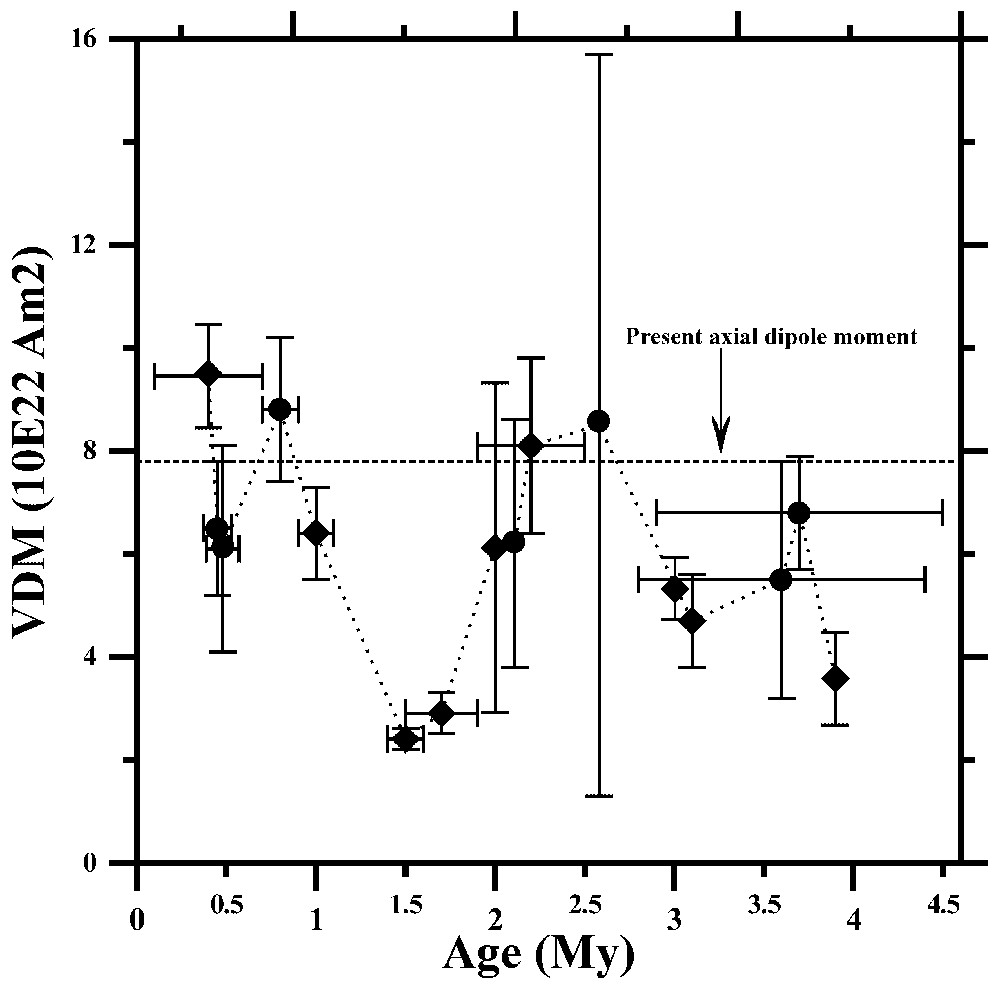

The site mean paleointensities range from 15.4±2.0 to 31.8±5.6 μT. The corresponding VDMs are ranging from 3.6 to 6.2×1022 A m2. There are not enough data to discuss VDM variation through Plio-Plestocene time and it is necessary to combine the Baja California results with previously published estimates from the same period of time (Table 2 and Fig. 4).

Average virtual dipole moment (1022 A m2) for various regions during Pliocene and Early/Middle Pleistocene. N refers to the number of cooling units used to calculate the average VDM. Asterisks refer to the mean values calculated discarding SBG results

Moment dipolaire virtuel moyen (1022 A m2) pour différentes régions au cours du Pliocène et du Pléistocène inférieur et moyen. N représente le nombre d'unités de refroidissement utilisées pour calculer le VDM moyen. Les astérisques représentent les valeurs moyennes calculées en ne tenant pas compte des résultats SBG

| Region | Age | N | VDM | S.D. | Reference |

| (Myr) | (1022 A m2) | ||||

| Oceanic Basalts | 3.9–2 | 3 | 5.2 | 1.8 | Juarez and Tauxe [21] |

| Oceanic Basalts | 3.9–0.4 | 3 | 4.9 | 2.8 | Selkin and Tauxe [39] |

| East Eifel | 0.49–0.35 | 7 | 6.5 | 1.3 | Schnepp [40] |

| Georgia | 3.8–3.6 | 3 | 6.8 | 1.1 | Goguitchaichvili et al. [16] |

| Central Mexico | 2.2–0.8 | 4 | 8.0 | 1.1 | Alva-Valdivia et al. [2] |

| SW Iceland | ∼2.58 | 3 | 8.5 | 7.2 | Tanaka et al. [42] |

| SW Iceland | ∼2.11 | 14 | 6.2 | 2.4 | Goguitchaichvili et al. [15] |

| West Eifel | 0.55–0.4 | 24 | 6.1 | 2.0 | Schnepp and Hradetzky [41] |

| Georgia | ∼3.6 | 6 | 5.5 | 2.3 | Goguitchaichvili et al. [16] |

| Baja California | ∼3 | 3 | 4.9 | 1.3 | This study |

| Total | 6.3 | 1.2 | |||

| Total∗ | 6.6 | 1.2 |

Virtual dipole moments against ages of volcanic units in Myr according to selected Plioocene and Early/Middle Pleistocene absolute intensity data (see also text and Table 2). Squares denote to the results from single cooling units while dots represent the mean value of several consecutive lava flows. In some cases, the error bars for the ages are missing because absence of adequate information (see also [2]).

Moments dipolaires virtuels en fonction des âges en Ma des unités volcaniques, d'après les données d'intensité absolue sélectionnées au Pliocène et au Pléistocène inférieur et moyen (voir aussi le texte et le Tableau 2). Les carrés représentent les résultats provenant d'unités individuelles refroidies, tandis que les points représentent la valeur moyenne de plusieurs coulées de lave consécutives. Dans certains cas, les barres d'erreur pour les âges ne sont pas indiquées en raison de l'absence d'informations adéquates (voir aussi [2]). Masquer

Moments dipolaires virtuels en fonction des âges en Ma des unités volcaniques, d'après les données d'intensité absolue sélectionnées au Pliocène et au Pléistocène inférieur et moyen (voir aussi le texte et le Tableau 2). Les carrés représentent les résultats provenant ... Lire la suite

In our analyses of the worldwide paleointensity data we considered only results: (i) obtained with the Thellier method; (ii) for which positive pTRM checks attest the absence of alteration during heatings; (iii) at least 3 determinations per unit; (iv) an error of the mean paleointensity about 20% or less; and (v) no data were considered from transitional polarity units. Moreover, we applied the same acceptance criteria on individual determinations as in present study (see above). Although 154 data are available from IAGA paleointensity database only 67 of them meet to our selection criteria. 23 selected determinations come from the studies published during last two years (Table 2, Fig. 4), and 7 of them belong to basaltic glasses [21,39]. We also note that the first three criteria are satisfied in the data of [4,7,8,44], but the cooling units studied belong to the transitional geomagnetic regime and were rejected from our analyses.

It cannot be ascertained that the remanence carried by SBG is of thermoremanent origin. Heller et al. [20] recently demonstrated that submarine basaltic glass probably contains a grain growth CRM (chemical remanent magnetization). The excellent technical quality of paleointensity data obtained from basaltic glasses, underlined by Juarez and Tauxe [21] is not by itself a proof of the geomagnetic validity of the paleostrength found. Goguitchaichvili et al. [13,14] showed that the magnetite found in this kind of material may be not of magmatic origin but crystallizes at rather low temperatures as a result of either glass demixtion or alteration. In such a case, the Thellier paleointensity results would underestimate the actual paleofield strength. Moreover, we still do not have any strict magnetic criteria to distinguish between TRM (thermoremanent magnetization) and CRM (crystalline remanent magnetization). Although, McClelland [26] theoretically predicted that CRM should yield a concave up Arai-Nagata diagrams, Körner et al. [22] and Goguitchaichvili et al. [13,14] do not observe this concavity. Microscopic observations may give sometimes decisive constraints to attest the TRM, but magnetic grains contained in baked sediments are too small to be observed directly by the reflected light microscopy. Keeping this in mind, we calculated the mean VDM by two different ways: (i) considering SBG results; and (ii) discarding them. In both cases, however quite similar results are obtained (Table 2).

The combination of Baja California data with the absolute intensity results currently available for Pliocene and Early/Middle Pleistocene, shows the VDM variation ranging from 2.41 to 9.45×1022 A m2 (Fig. 4) yielding a mean VDM of 6.3×1022 A m2, which is about 80% of the present geomagnetic axial dipole (7.8×1022 A m2 after Barton et al. [3]). Reliable absolute paleointensity results for the last 5 Ma are still scarce and of dissimilar quality. Additional high quality determinations are needed to better document the geomagnetic field strength during the Plio-Plesitocene.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by CONACYT projects J32727-T, 25052T and UC-MEXUS grant.

AG is grateful to the financial support given by UNAM IN100403.