Version française abrégée

Un des objectifs des sciences de la Terre est de comprendre les variations climatiques qui se sont produites depuis la formation de notre planète jusqu'à nos jours et, au-delà, de proposer des scénarios d'évolution future.

La recherche menée sur les périodes récentes a été renforcée depuis la mise en évidence de l'augmentation du CO2 atmosphérique, mais aussi de la température globale de la Terre. La compréhension des variations importantes de température qu'a subies notre planète a, elle aussi, beaucoup progressé depuis 20 ans. L'article qui a stimulé ces études est celui de Walker et al. [106]. Deux idées principales ont été présentées. La première est l'identification des paramètres clés qui contrôlent la température de la Terre : la quantité d'énergie reçue au sommet de l'atmosphère terrestre en provenance du soleil et la concentration en gaz à effet de serre tels que le CO2. Cette concentration est contrôlée, d'une part, par l'activité interne de la Terre (dégazage de CO2 par le volcanisme) et, d'autre part, par l'altération des roches, qui consomme du CO2 atmosphérique et permet in fine de stocker le CO2 au fond des océans sous forme de carbonates. La seconde idée majeure est l'hypothèse d'un mécanisme de régulation de la température engendré par la relation positive qui peut exister entre « intensité de l'altération » et « température de la Terre ». Ce mécanisme conduit à équilibrer les flux d'entrée et de sortie de CO2 dans l'atmosphère et limite les variations climatiques de notre planète.

Le second article qui a fortement contribué aux débats est celui de Raymo [97], qui a repris d'anciennes idées concernant l'influence des chaı̂nes de montagnes sur le climat de la Terre. L'idée simple est que les chaı̂nes de montagnes favorisent l'altération des roches et donc augmentent la consommation de CO2, entraı̂nant un refroidissement de la Terre.

Ces deux modèles ont souvent été opposés et la discussion a été très vive [60,61]. Une grande partie du débat venait en fait de l'absence de données permettant de discuter les lois d'érosion. De nombreux résultats récents ont permis d'avancer dans ce domaine. Ce travail a été fait à partir de l'étude des grands fleuves du monde, ainsi que sur de petits bassins monolithologiques, ce qui a permis d'obtenir des flux d'altération avec une meilleure prévision qu'auparavant. Avant d'aborder les lois d'érosion, il est nécessaire de quantifier l'origine des éléments dissous dans les rivières (carbonate, silicate, apports atmosphériques, évaporite).

Les résultats important sont les suivants.

(1) Découverte du rôle de l'altération des basaltes sur le cycle de CO2 [31,75,76]. Les basaltes continentaux consomment près de 30 % du CO2 par rapport à l'ensemble des roches silicatées. Ceci est dû à leur très forte altérabilité, qui est près de huit fois supérieure à celle des granites.

(2) Découverte d'une loi simple pour modéliser l'altération des basaltes. Le flux de CO2 consommé par l'altération des basaltes est proportionnel à la surfaces des basaltes, au ruissellement continental (lame d'eau écoulée en ) et à la température moyenne annuelle de la région considérée [32].

(3) Absence de loi simple pour l'altération des granites. Aucune loi simple n'a été trouvée pour l'altération des granites. Oliva et al. [88] ont montré que l'effet de la température n'était visible que pour les régions à haut ruissellement. L'absence de relation pour les bas ruissellements est principalement liée à la nature des sols, qui peuvent être très épais et faire écran par rapport aux roches « fraı̂ches » [50,101,105]. Néanmoins, ce résultat ainsi que celui obtenu sur les basaltes permet de confirmer le rôle de la température sur l'altération à l'échelle globale.

(4) Loi générale reliant érosions chimique et mécanique. Une loi générale a été proposée, qui relie l'érosion chimique et l'érosion mécanique. Cette loi a été observée sur les grands bassins versants [53] et confirmée sur les petits [83].

À partir de ces travaux récents, il a été possible de préciser de manière quantitative les effets des grands phénomènes géologiques sur le climat de notre planète.

(1) La mise en place des grandes provinces basaltiques modifie sans doute le climat de la Terre sur des périodes de l'ordre du million d'années, avec un stade de réchauffement suivi d'un stade de refroidissement. Dans le cas de la mise en place des trapps du Deccan il y 65 millions d'années, le réchauffement aurait été de 4 °C et le refroidissement de 0.5 °C [31]. La mise en place de trapps au Néoprotérozoı̈que, entre 825 et 725 Ma, pourrait avoir provoqué un refroidissement important, permettant à notre planète de rentrer dans une période de glaciation totale, snowball Earth [59].

(2) La relation entre érosion mécanique et érosion chimique appuie l'idée d'une influence de la formation des chaı̂nes de montagnes sur le climat. Nos derniers résultats montrent que la formation des chaı̂nes andine et himalayenne peut avoir joué un rôle très important en termes de consommation de CO2 depuis environ 20 Ma.

D'un point de vue plus général, la découverte de ces lois d'érosion et les progrès effectués sur les modèles climatiques permettent d'envisager des modèles couplés climat/cycles biogéochimiques, indispensables pour la reconstitution du climat passé de notre planète. Il reste à mieux définir le rôle de la végétation sur l'altération. Ce paramètre, mal contraint à l'heure actuelle, est en effet indispensable pour mieux comprendre l'évolution du climat lors de la mise en place de la végétation sur les continents (fin du Dévonien). Enfin, il est important de prendre en considération les gaz à effet de serre autres que le CO2 et le cycle organique du carbone.

1 Introduction

Continental chemical weathering is a key process of the Earth global geochemical cycles. Of particular interest is the CO2 cycle, since atmospheric CO2 is a greenhouse gas directly impacting on the Earth global climate. At the geological timescale, this cycle is essentially driven by two processes: the CO2 degassing through arc volcanism, degassing at mid-oceanic ridge (MORB emplacement) and metamorphism (which act as sources of CO2 [70]), and the consumption through weathering of continental silicate rocks and the storage of organic carbon in sediment. Chemical weathering of Ca-silicates can be described by the following generic expression [12]:

The quantification of this weathering sink relies on field studies performed at various time and spatial scales. The multidisciplinary studies on small watersheds [18,25,36,37,58,75,76,81,89,92,105,108,109] are complementary to those carried out at larger scale using the main rivers in the world [19,38,40,41,44,50,52–54,90,100,101,104]. These two approaches use the same type of data, which are the chemical composition (majors cations and anions, dissolved organic carbon – DOC –, particulate organic carbon – POC –) of the dissolved and particulate phases of rivers, the total masses of dissolved elements (TDS) and suspended sediments (TSS). Simple parametric laws, describing the dependency of chemical weathering on environmental factors are then established, based on these field studies. Such kind of laws are then introduced into numerical models describing the biogeochemical cycles, themselves used to calculated the evolution of the partial pressure of atmospheric CO2 through times.

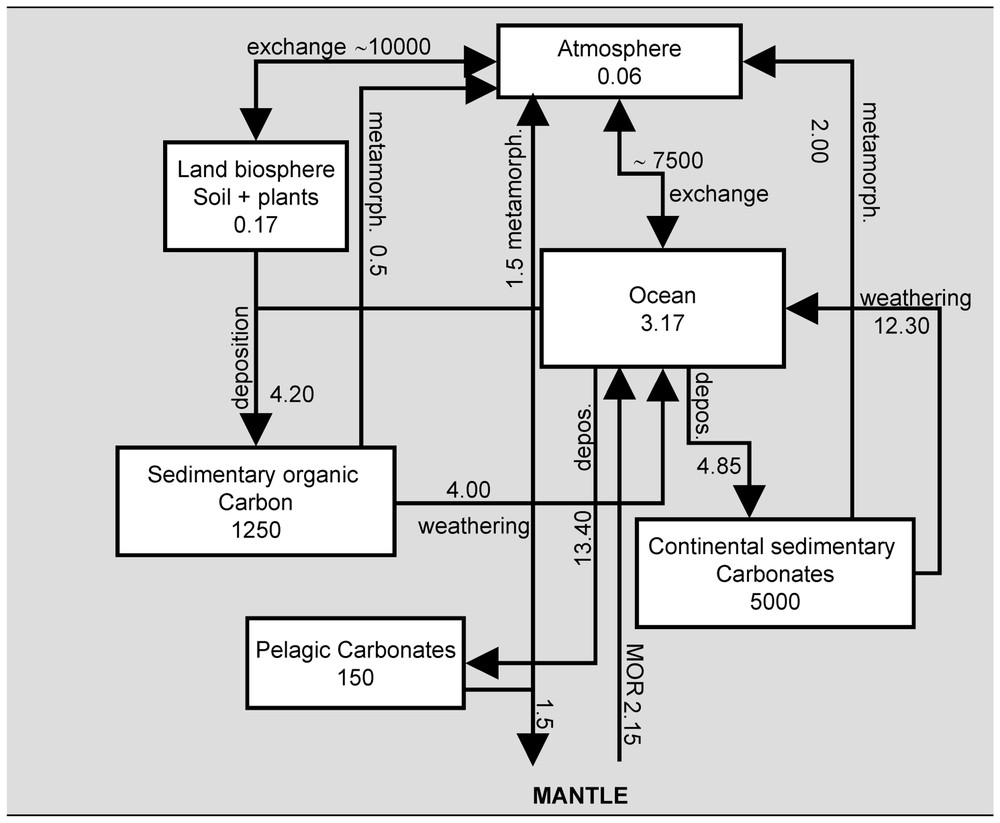

The global biogeochemical cycle of carbon has been described and quantified during the last 50 years, including the description of the surficial carbon stocks and of the exchange fluxes (Fig. 1). The atmosphere is by far the smallest reservoir, with a quite short residence time (about three years), implying that rapid fluctuations of the atmospheric carbon content are allowed at least at the decadal timescale, inducing global climate changes. Although longer, the residence times of carbon in the biosphere (including soil carbon) and in the ocean do not exceed several centuries. At the geological timescale, the evolution of the total content of the oceanic, atmospheric and biospheric reservoirs is controlled by the exchanges with geological reservoirs displaying residence times from about 107 to 108 years, through weathering, deposition and metamorphic processes. These reservoirs include sedimentary reduced and oxidized carbon stocks, and the mantle. Although quite small compared to the carbon exchanges between the ocean and atmosphere, or between the biosphere and the atmosphere, the weathering processes are thus the main controlling factors of the evolution of the atmospheric carbon stock and global climate through geological ages.

Present-day global carbon cycle. Reservoir contents are expressed in 1018 moles of C, while the fluxes are expressed in of C (adapted from Prentice et al. [91]; François et Goddéris [46]). The ocean–atmosphere reservoir is assumed to be at a steady state against geological processes. The values for the exchange fluxes give the order of magnitude of these fluxes, without accounting for disequilibrium within the exchanges.

État moderne du cycle du carbone. Le contenu des réservoirs est exprimé en 1018 moles de C, et les flux en 1012 moles de C an−1. (adapté de Prentice et al. [91] ; François et Goddéris [46].) Le réservoir océan–atmosphère est supposé à l'équilibre vis-à-vis des processus géologiques. Les valeurs des flux d'échange donnent l'ordre de grandeur, sans tenir compte des déséquilibres au sein même des échanges.

In the following, we will first describe our general understanding of the long-term evolution of the carbon cycle. We will focus on the driving processes, and on the numerical models that were implemented to calculate the partial pressure of atmospheric CO2 and climate through the geological past. Then we will discuss the degassing flux originating from the Earth interior into the ocean–atmosphere system, as the main long-term source of carbon. The next section will focus on the main long-term sink of carbon: continental silicate weathering. We will particularly discuss the procedures followed to estimate global weathering laws, as well as the limitations encountered. Finally, we will show how the introduction of new weathering laws, based on the recent works by the Toulouse and Paris teams, leads to the implementation of new models of past atmospheric CO2.

2 Chemical weathering of continental silicate rocks and numerical models of the geochemical cycles

2.1 Basic concepts

All existing numerical models describing the evolution of the global biogeochemical cycles at the geological timescale are based on the work by Walker et al. [106]. These authors argue for a direct dependency of continental silicate weathering on climate (silicate weathering increases with temperature and runoff, both enhanced under higher pCO2 values). Since silicate weathering is the main CO2 sink at the geological timescale, the mathematical expression proposed by Walker et al. [106] provides the expression of the negative feedback stabilizing the Earth climate at the geological timescale: for instance, any increase in the degassing rate will be directly compensated by an increase in the sink of carbon through silicate weathering, under enhanced greenhouse effect. Note that the general framework of this idea can be traced back in the 19th century [39], as noted by Berner and Maasch [13].

The most standard mathematical expression for the consumption flux of CO2 by the weathering of a given exposed surface of silicate rocks Fsil might be written as follow:

| (1) |

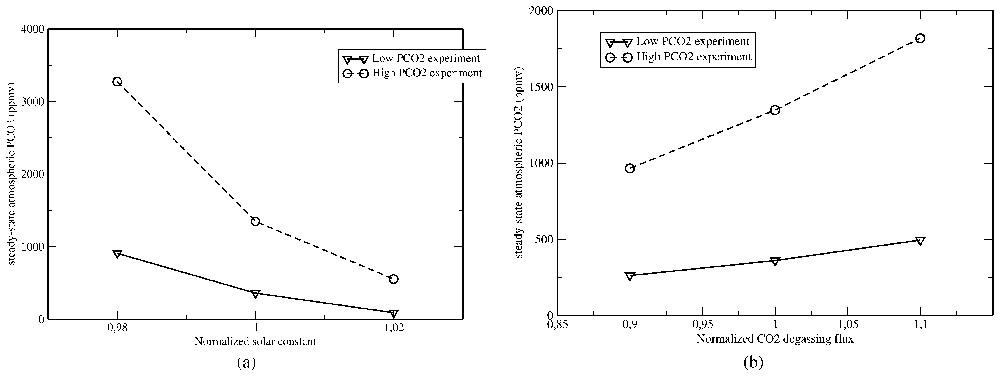

At the geological timescale (106 to 109 years), the main factors driving the climate, in close connection with silicate weathering, are the solar constant, CO2 degassing rate and continental configuration. In order to quantify the relative importance of these processes, we use a simple model described in the legend of Fig. 2. The solar constant appears to have an extremely important impact on the global carbon cycle, since a change in the solar constant by only 1% results in an almost 200% change in the atmospheric pCO2 (Fig. 2a). The same pCO2 fluctuations are obtained if degassing rate changes by 10% (Fig. 2b). Any change in the carbon source fluxes by a few percent might thus have a potentially major impact on the Earth global climate. Finally, Fig. 2c shows the impact of continental configuration on the global carbon cycle, illustrating the effect of a perturbation in the carbon sink flux (here silicate weathering) on the atmospheric pCO2. For instance, when continents are located around the pole, global continental temperature and runoff tend to decrease, leading to an inhibition of silicate weathering. If CO2 degassing remains constant, atmospheric pCO2 will rise until continental climatic conditions will allow silicate weathering to compensate for the CO2 source.

Sensitivity of the CO2 atmospheric partial pressure to external parameters. A simple energy balance model [47] is used to calculate the zonal air temperature and zonal continental runoff (the latter through a simple parametric law) in 18 latitude bands for a given continental configuration and solar constant, as a function of the atmospheric pCO2. It allows the calculation of the zonal and global consumption of atmospheric CO2 by continental silicate weathering (Eq. (1)), which reaches under 360 ppmv of CO2. Assuming that the carbon cycle is at steady state under present-day conditions, this CO2 consumption flux should exactly compensate for a CO2 degassing flux through volcanism and ridge activity of . (a) The solar constant has been increased and decreased by 2%, and in both case we calculate the atmospheric CO2 level (and hence climate) triggering a total consumption of CO2 by silicate weathering () that compensates exactly for the degassing flux (forcing the inorganic carbon cycle at steady state), through a simple convergence algorithm. The lower sensitivity of global climate to change in pCO2 at high atmospheric levels results in a higher sensitivity of pCO2 to solar constant changes. (b) We then test the impact of changing the degassing rate by 10% under fixed solar constant and continental configuration through the same procedure. Atmospheric pCO2 increases and climate is getting warmer and wetter if CO2 degassing increases, allowing the consumption of CO2 through continental silicate weathering to compensate for the increase in the CO2 source. (c) Finally, we explore the impact of the general continental configuration on the pCO2 level. The ‘polar’ test was performed assuming that all continents are located above 25° latitude (symmetrical distribution for both hemispheres, present-day total continental surface unchanged). This configuration results in an increase in atmospheric CO2 compensating for the decrease in temperature and runoff triggered by the high latitude location of continental surfaces. The ‘equatorial’ run was performed by assuming that all continental surfaces are located symmetrically along the equator within −25° and +25° latitude.

Sensibilité de la pression partielle en CO2 atmosphérique aux paramètres externes. Un modèle simple de balance énergétique [47] est utilisé pour calculer la température zonale de l'air et le ruissellement continental zonal (ce dernier au travers d'une loi paramétrique simple), dans 18 bandes de latitude, pour une configuration continentale, une constante solaire et une teneur en CO2 données. La température et le ruissellement continental permettent alors le calcul de la consommation zonale et globale de CO2 atmosphérique par altération des silicates continentaux, qui atteint sous une pCO2 de 360 ppmv. Supposant que le cycle du carbone est à l'équilibre sous les conditions actuelles, cette consommation de CO2 est supposée compenser exactement le dégazage de CO2 par l'activité volcanique et aux dorsales océaniques de . (a) La constante solaire a été accrue et diminuée de 2%, et dans les deux cas nous calculons la teneur en CO2 (et donc le climat) entraı̂nant une consommation de CO2 par altération des silicates continentaux (Éq. (1)) (11,7×1012 moles/an) qui compense exactement le dégazage (forçant ainsi le cycle inorganique du carbone à l'équilibre), à l'aide d'une simple procédure de convergence. La sensibilité plus faible du climat global vis-à-vis de changements de pCO2 à de hautes valeurs atmosphériques entraı̂ne une sensibilité plus grande de pCO2 aux changements de constante solaire. (b) Nous testons ensuite l'impact d'un changement du taux de dégazage de CO2 de 10%, constante solaire et configuration continentale fixées, en utilisant la même procédure. Le CO2 atmosphérique augmente et le climat devient plus chaud et humide si le dégazage augmente, ce qui résulte en une augmentation de la consommation de CO2 par altération des silicates, compensant l'augmentation de la source de CO2. (c) Finalement, nous explorons l'impact de la configuration continentale générale sur le niveau de CO2 atmosphérique. Dans le test « polar », l'ensemble des surfaces continentales a été déplacé au-dessus de 25° de latitude (la distribution continentale est symétrique de part et d'autre de l'équateur, la surface continentale totale est maintenue à sa valeur actuelle). Cette configuration provoque une augmentation de la teneur en CO2 atmosphérique, afin de compenser la diminution de température et de ruissellement, liée à la localisation à hautes latitudes des surfaces continentales. La simulation « équatoriale » a été réalisée en localisant l'ensemble des surfaces continentales entre −25° et +25° de latitude.

2.2 A short model review

The first numerical models (0D, thus neglecting the continental drift factor) calculating the pCO2 evolution through the geological history all include a forcing function for the degassing rate and the long-term evolution of the solar constant [7–9,14,15,74]. In addition to controls exerted by changes in the solar constant (slow secular change, that will produce slow secular response in pCO2), silicate weathering is tracking changes in the degassing rate (rapidly fluctuating forcing) through the negative climatic feedback. The calculated atmospheric pCO2 is thus heavily dependent on the adopted degassing forcing function (which is poorly constrained; [42,49,72]), and on the mathematical formulation adopted for silicate weathering (Eq. (1)). CO2 degassing acts as the main force of change at the geological timescale (Walker's world).

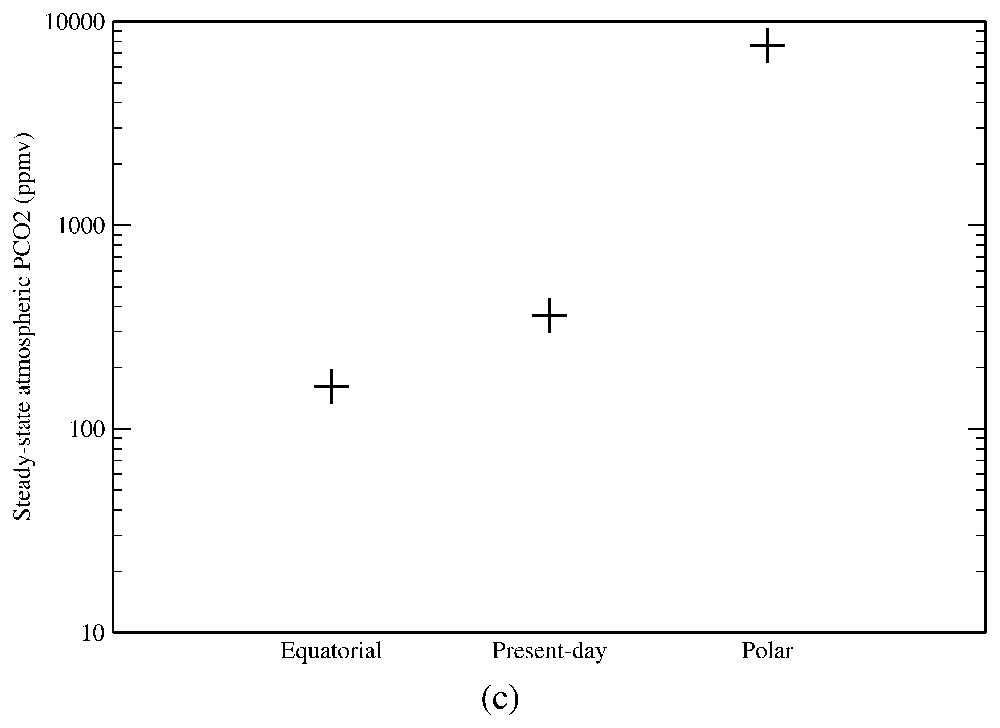

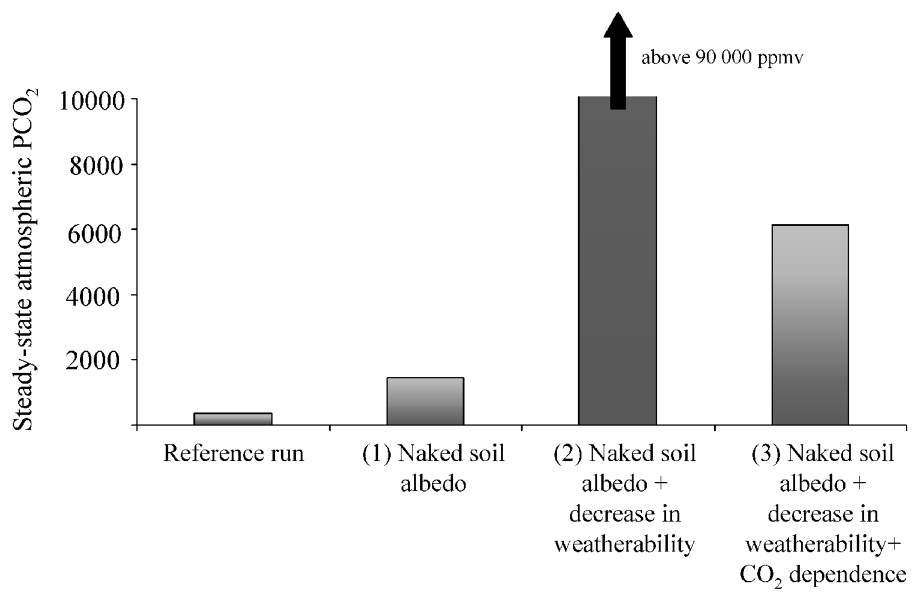

Second-generation models appear in the early and middle 1990s and are still in development [47,48,60,62]. Those models strongly improve the climatic module of global biogeochemical models, through the complete coupling with a 1D energy-balance model. Such simple climatic model allows the calculation of air temperature in 18 latitude bands as a function of zonal continental configuration, and atmospheric CO2. Runoff is estimated zonally through simple parameterisation, involving continental configuration and air temperature. François and Walker's work [47] was the first attempt to account for the role of palaeogeography within the global carbon cycle. At the same time, the impact of continental vegetation (particularly vascular plants) on weathering rates of silicate rocks were included in improved 0D geochemical models [9–11]. This impact of continental vegetation on calculated atmospheric CO2 is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Impact of global continental vegetation on atmospheric pCO2. We use the same procedure as in Fig. 1. The continental configuration, solar constant and degassing rate are kept constant at their present-day values. Several tests illustrating the impact of the removal of the continental vegetation are performed: (1) only continental albedo is assumed to be affected (rising on the continents to a constant value of 0.3, typical of naked soils), tending to cool the global climate, counteracted by an increase in pCO2 that stabilizes around 1500 ppmv; (2) in addition to albedo effect, we assume that continental weatherability is decreased by a mean factor of 6.6 in the absence of vegetation [11]; (3) we further assume a direct dependence on CO2 of continental weathering, even in the absence of land plants (pCO20.5).

Impact de la végétation continentale globale sur la teneur en CO2 atmosphérique. On a utilisé la même procédure que pour la Fig. 1. La configuration continentale, la constante solaire et le taux de dégazage sont maintenus constants à leur valeur actuelle. Nous avons réalisé plusieurs tests illustrant l'impact de l'absence de végétation continentale : (1) seul l'albédo continental est affecté (celui-ci est augmenté à 0,3, une valeur typique des sols nus), ce qui tend à refroidir le climat global. Cette tendance est compensée par une augmentation de pCO2, qui se stabilise aux alentours de 1500 ppmv ; (2) en plus de l'effet d'albédo, nous supposons que l'altérabilité continentale diminue d'un facteur 6,6 en l'absence de végétation [11] ; (3) nous ajoutons au test précédent une dépendance directe de l'altération continentale des silicates vis-à-vis de pCO2, même en l'absence de végétation continentale (pCO20.5).

The new 1D models together with improved 0D models [29,60,71] were used to test a new hypothesis about the role of mountain building on the global carbon cycle. The impact of orogenesis (particularly the Himalayan uplift) on the global carbon cycle and climate has been deeply investigated since the early 90s within the publications by Raymo and co-authors [29,60,61,71,94–97] based on the early work of Chamberlin [24]. They were postulating that atmospheric carbon is being consumed by enhanced chemical weathering of Ca- and Mg-silicate rocks exposed within the Himalayan range as a result of enhanced mechanical breakdown. Raymo suggested that the resulting global cooling would finally enhance silicate weathering all over the world through a positive feedback loop, cooling favouring mechanical weathering, itself increasing consumption of CO2 by chemical weathering of silicate rocks. In this scenario, the main force of change is the continental silicate weathering, driven by mechanical weathering, itself controlled by tectonic processes (Raymo's world). Although appealing, this hypothesis leads to the existence of long-term disequilibria between the CO2 outgassing and the consumption by continental silicate weathering, through the decoupling of both fluxes. As a result, unacceptable fluctuations of the exospheric carbon and oxygen contents are calculated [29,61].

Today, new models must be developed that include all recent studies of continental weathering performed on small watersheds and large rivers. For instance, the recent inclusion of lithologic effect within 0D and 1D models (particularly the basaltic surfaces) brings the description of the geochemical cycles to a new degree of complexity [31,59,103,107], as will be described below.

3 CO2 sources: the control of the CO2 cycle by the internal dynamic of the Earth

Earth is a living ‘planet’ that continues to release heat through volcanism but also some gases like carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4). Being greenhouse gases, they directly impact on the climate. The long-term evolution of the Earth surface was thus at least partly controlled by its internal activity. Since the discovery of plate tectonics, a general frame has been adopted that describes the formation of basaltic rocks. If we consider recent basalts (less than 1 billion year old), four main types of basalts are identified: Islands Arc volcanisms (IAV), Mid Oceanic Ridge Basalts (MORB), Oceanic Island Basalts (OIB) and Continental Flood Basalts (CFB). Only IAV and MORB are located at the plate boundaries. However, there are few exceptions, like Iceland that does not belong to the OIB group. MORB originate from the upper mantle, while OIBs are generally considered as derived from deeper source [1]. New OIB are very often associated with a particular type of basalts, the continental flood basalts (CFB). This volcanism produces huge amounts of mainly tholeiitic basalts in a very short time period [26,27]. The emplacement of CFB can occur within continental or oceanic environment. The geochemical signatures (trace elements and radiogenic isotopes) of CFB are very variable and differ from those of MORB and OIB [2,64].

The melting of IAV is due to the dehydration of the subducted lithospheric plate, and the use of radiogenic tracers like lead, strontium and neodymium demonstrates the presence of sediments within the source of basalts [3,111].

The degassing of CO2 is directly related to the mantle dynamic and recently proposed ideas allow the estimation of the degassing rate during the geological times. The first attempt in reconstructing Phanerozoic seafloor accretion rate was performed by Gaffin [49], based on the inversion of the sea-level curve. This rate has been used in several global biogeochemical models [8,15,47] to force the degassing rate. In 1992, Caldeira [22] suggests that the degassing rate was not only a function of the seafloor accretion rate, but also of the amount of carbonates accumulated on the seafloor and being partly degassed into the atmosphere at subduction zones. Such process has been included in revised versions of the François and Walker model [45,48,60]. This scenario has been recently rethink and somewhat improved by Schrag [99], suggesting that the efficiency of the carbonate recycling might be an underestimated process controlling the global carbon cycle. Finally, we have proposed that the timing of the CFB emplacement plays a very important role in the climate evolution of the Earth [31,59].

Some other parameters should be considered in the future. What is the effect of the presence of a ‘super’ continent at some periods of the Earth history on the emission of CO2 in the atmosphere? At this time, heat is accumulated below continental masses until the breakdown of continent is initiated by CFB (and related intense degassing). This hypothesis of heat storage is in agreement with the results obtained by Humler and Besse [67] on the high temperature of the old Atlantic tholeiitic basalts by comparison with recent mid-oceanic ridge basalts. What is the effect of changing the volcanic emission due to strong modifications in the mantle as proposed by Machetel and Humler [78]? What is the effect of other types of volcanism on the CO2 such as the onset of carbonatites? All these questions need more studies but we have to keep in mind that the reconstruction of the CO2 source coming from the mantle is still poorly constrained.

Another important information about the CO2 cycle can be assessed using carbon isotopes on MORB. Javoy et al. [69] have proved that one fraction of the superficial carbon has necessarily been reinjected in the mantle.

4 CO2 sinks: chemical weathering of silicates

River chemistry integrates the contribution of several sources: atmospheric input+chemical weathering ± biospheric effect ± ion-exchange effect.

However, at the watershed scale, looking at output fluxes of elements, there are only two ultimate sources that must be considered: the atmosphere (the external source) and the local chemical weathering (water–rock interactions). Elements involved in the vegetation cycling or in ionic exchange processes are ultimately originating from these two sources. Until now, the quantification of the atmospheric deposits on the watershed (aerosol, wet and dry deposits and throughfall contributions) is not well constrained. This is particularly due to the lack of data but also to the problem of identifying the exact origin of the elements coming from the atmosphere; indeed, atmospheric deposits may bring elements that originate from the watershed itself (local re-emission) and make the correction on the output fluxes hazardous. This correction is important because the concentration of major elements (with the exception of Si) in rivers flowing on silicate rocks can be in the range of those measured in rainwater.

Most rivers drain a variety of rock types. Easily weathered lithologies are therefore expected to dominate the river chemistry. Saline evaporite rocks and carbonates have been shown by Meybeck [82] to weather on average 10 to 100 times faster than silicate lithologies. Hydrothermal deposits or volcanic sublimates are likely to be dissolved very quickly as well. As far as silicate-weathering rates are concerned (and associated CO2 consumption), it is necessary to correct from the non-silicate inputs to river chemistry. Several techniques have been used to calculate the proportion of each major solute, from Garrels and Mackenzie [56] to Negrel et al. [86]. The last method uses chemical Na-normalized ratios (Ca/Na, Mg/Na) and Sr isotopic ratios as proxies of carbonate-versus-silicate dissolution and an inverse method to determine the proportions of each mixing end-member. Even in purely silicated catchments, a number of studies have shown that the presence of disseminated or vein calcite can have a major influence on river chemistry and that calcite-derived dissolved Ca (and associated C) has to be corrected, because it does not originate from the atmosphere [16,35,55,110]. This issue still remains a difficult task. Finally, in volcanic provinces, or even in central Himalayas, authors have shown the major role played by hydrothermal sources [4,33,43,75]. Again, the estimate of silicate chemical denudation rates requires that solutes from hydrothermal inputs must be disregarded, as hydrothermal carbon is mostly derived from volcanic or metamorphic degassing and not from the atmosphere.

With errors inherent to the correction methods, weathering rates of silicates (usually in ) can thus be calculated (sum of major cations and silica) for a variety of catchments and regions with different climatic and geomorphologic features, and then compared. Note that CO2 consumption rates are not necessarily correlated to silicate weathering rates when oxidative weathering of sulphides provides protons to the soil solution.

The search for chemical weathering laws is made by comparing the so-calculated weathering rates with parameters like runoff (net precipitations), mean annual temperature, mean slope, watershed size, mechanical erosion fluxes, anthropogenic impact. Among these parameters, basin drainage size is probably the best-known parameter. However, when annual runoff is used, information is lost on the yearly runoff variability. Mean air temperature is also a questionable parameter that has only a sense when the annual variation is weak and positive. Finally, the third difficulty is to get a reliable estimation of river fluxes. Very often, mean water discharges are compared to a solute concentration determined at the time of sampling, and discharge-averaged concentrations are rare. This is particularly true for small drainage basins in which the influence of century floods on the transport of solutes can be huge. In large rivers, recent progresses have been made on the estimation of fluxes using new techniques like ADCP [23,63].

A fundamental aspect of the future works in this field is to continue to improve the quality and the quantity of data.

It is important to keep in mind the questions related to the quality of the data, but also the simplifications introduced by using mean annual parameters. Some questions discussed thereafter may be linked to these previous remarks.

5 Chemical silicate weathering laws

The determination of chemical weathering laws is required to model the evolution of CO2 in the atmosphere during the history of the Earth. The aim is to establish simple laws that can be easily used in global and low-resolution models. In agreement with experimental data on the weathering of silicate minerals some of the main parameters used to define chemical laws are runoff, pCO2, soils properties, pH, temperature, pluviometry.

Attempts to establish parametric laws of silicate chemical weathering using rivers have been made using both large river systems and drainage basins draining a single type of rock. Large rivers have the advantage to integrate (and average) information over large areas, but generally result from a mixing of diverse lithologies. Smaller rivers (order 1) can be chosen for draining a single lithology but are more sensitive to small variations in hydrology, rock mineral composition (trace minerals) and may not be representative of larger scale. In fact the results obtained by these two approaches are very similar and complementary.

5.1 Large-scale approach

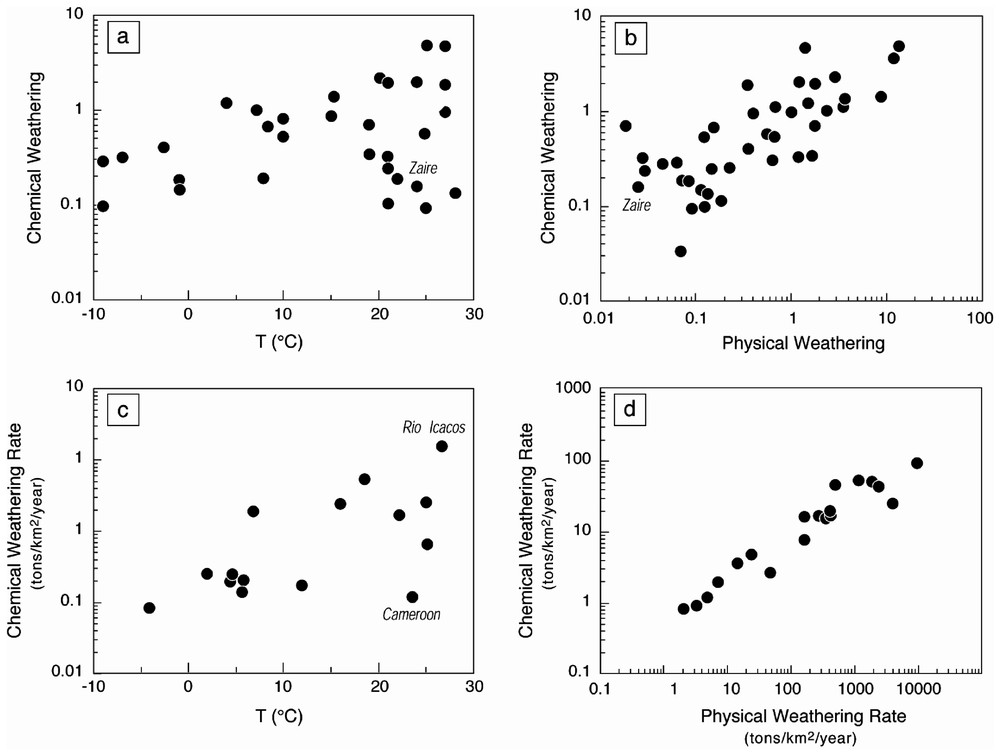

Continental silicate reservoir component corresponds to a complex mixing of various lithologies (granites, shales, mafic rocks, volcanic rocks...) integrated over large surface areas. Based on a global compilation, Gaillardet et al. [53] extract the silicate component from the 60 largest rivers of the world and showed that runoff is the most evident controlling parameter of chemical denudation rates for silicates and associated CO2 fluxes. The role of temperature has been shown to be less clear (Fig. 4a), with a majority of rivers showing increasing weathering rates of silicates with increasing temperature and a couple of rivers, especially tropical lowland rivers, deviating from the global trend. The good correlations observed at a global scale between physical denudation fluxes and chemical-weathering fluxes of silicates (Fig. 4b) suggested to the authors that chemical weathering and physical erosion are intimately coupled. Low physical denudation regimes preclude water–rock interactions and lead to low solute fluxes, even if mineral weathering reactions are complete and lead to the formation of gibbsite and kaolinite. The chemical inspection of the suspended sediments transported by large rivers [51] also confirmed that the rivers of high chemical denudation silicate fluxes transport poorly weathered material, compared to the mean continental crust composition. Conversely, large catchments (Congo, lowland tributaries of the Amazon) showing highly weathered sediments (highly depleted in the more mobile elements during weathering reactions) exhibit low chemical weathering fluxes of silicates.

Correlation between silicate chemical weathering and temperature (Fig. 4a), and physical erosion (Fig. 4b) for large watersheds. The values are normalised to the Amazon watershed; see Gaillardet et al. [53]. The Huanghe River has been removed, due to the strong effect of deforestation on the mechanical weathering. Fig. 4c and d give the same relationship for small monolithological watersheds.

Relation entre l'altération chimique des silicates en fonction de la température (Fig. 4a) et de l'érosion mécanique (Fig. 4b) pour les grands bassins fluviaux. Les valeurs sont des valeurs normalisées au bassin de l'Amazone afin de tenir compte de la présence de carbonate sur les grands bassins fluviaux (voir Gaillardet et al. [53]). Le fleuve Jaune a été éliminé de la base de données, du fait du très fort impact de la déforestation dans ce bassin versant. Les Figs. 4c et d présentent les mêmes relations pour les petits bassins silicatés monolithologiques.

5.2 Chemical weathering of granites

Using a database of more than 60 different small watersheds draining granitoid rocks, White and Blum [108] have recently emphasized the role of temperature on silica fluxes and weathering rates. This database has been completed by Oliva et al. [88] and a careful treatment of the data showed that the relationships between temperature and weathering rates are not so simple that previously proposed [108] (Fig. 4c). In particular, all data from lowland tropical environments are characterized by remarkably low denudation rates [89,104]. Oliva et al. [88] showed that the positive influence of temperature is only clear when runoff values are higher than . The relationship between temperature and chemical denudation leads to an activation energy of about , close to the values determined by experimental studies of silicate dissolution [98]. We suggest that a ‘soil-effect’ explains why the relationship between chemical weathering rates and temperature is only observed at high runoff. High runoffs are often associated with mountainous areas where soils are constantly dismantled. In the lowlands, the formation of thick soils protects the bedrock from chemical weathering, with no primary minerals remains in thick tropical soils [85]. This shielding effect of soil was outlined for the Amazon and Guyana shield by Stallard and Edmond [101]. It is important to note that this result, inferred from a global systematic of small drainage areas, is consistent with those inferred from large basins.

The relationships between chemical and physical erosion fluxes have been attempted by Millot et al. [83] (Fig. 4d). The number of granitic catchments for which physical erosion fluxes have been measured is very low. However, the same relationship holds for the largest rivers as well.

We have recently proposed that other parameters also play an important role in the chemical weathering rate. Oliva et al. [87] have reinforced the idea that trace minerals could play a significant role in the CO2 consumption in a young soil environment developed on rocks recently glaciated (Estibere watershed). This last study reveals that 80% of the CO2 consumption is due to the alteration of silicate trace minerals. This effect of increased weathering was already observed for other high altitude watersheds [5,17,110]. This new observation reinforces the proposition of Stallard [100] about the effect of the soil age. Other important parameters are certainly the strong mineralogical and chemical heterogeneities of the ‘granitoids’ [87].

Other observations have been reported on the relationship between the dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and the chemical weathering. Although the link might appear rather weak and has to be confirmed by future works, Oliva et al. [89] have proposed that the organic matter through complexation with acidic functional groups enhances the chemical weathering by about 20%. This result arises from a study performed in a small watershed in Cameroon. In study carried out in Canada, Millot et al. [84] have shown a clear relationship between DOC and silicate chemical weathering. It is rather difficult to use directly this information in models, but these observations highlight the role of the vegetation in weathering processes. This debate is still open, and even if some other recent studies have clearly shown a direct impact of the vegetation on the weathering [10,113], it is still extremely difficult to estimate the long-term effect of the continental vegetation on weathering. Indeed, vegetation cover is not only involved in chemical processes but plays also a physical role by protecting soils from strong mechanical weathering.

5.3 Chemical weathering of basalts

Unlike granitic watersheds, the chemical weathering and CO2 consumption fluxes due to basalt weathering have been poorly studied. However, several authors [58,75,76] have shown that basalts are among the more easily weathered rocks in comparison with other crystalline silicate rocks. Therefore, basalts play a major role in the carbon cycle and the contribution of basaltic rocks to the continental weathering flux must be estimated. It is thus necessary to determine the weathering laws of basalts and devise the best method of describing how these rocks weather under different climates. Using a database of river waters for 12 different basaltic provinces, it appears that runoff and temperature are the main two parameters that control the chemical weathering of basalts [32]. We obtain an apparent activation energy around , similar, within the error bars, to the granitic values. The consumption of atmospheric CO2 by basalt weathering can be written as [32]:

Thanks to this relationship, it is now possible to determine, for any basaltic province, the chemical weathering rates and associated CO2 consumption rates, provided that the temperature and the runoff are known over this basaltic province. Moreover, from our relationship and several digitised maps (basaltic outcrops, mean annual runoff and temperature), the calculated global CO2 flux consumed by chemical weathering of basalts reaches about , representing between 30 to 35% of the flux derived from continental silicate including islands studied by Gaillardet et al. [53]. This study reinforces the idea of the very important contribution of basalts to the global flux derived from silicate weathering. However, in the future, an important effort should be invested to obtain more complete data of rivers flowing through basalts, in order to better understand the processes governing chemical weathering of basalts and to emphasize the impact of some other parameters (age of rock, vegetation, soil thickness...).

6 Modelling

6.1 Importance of chemical weathering in global change

As discussed above, chemical weathering of continental silicates acts as the main sink of carbon at the geological timescale. This flux has been neglected in all recent studies dealing with the global climatic changes triggered by anthropic activities, because chemical weathering of all lithologies consumes only about [53,77], compared to the absorbed by the ocean, or the consumed by continental photosynthesis [91]. However, the consumption by weathering can be seen as a net output flux on short timescales (101 to 102 years), independently from the lithology being eroded. When considering net fluxes, the continental biosphere releases of carbon into the atmosphere, while the ocean consumes only of carbon [91]. These numbers are of the same order of magnitude as the consumption of carbon by continental weathering. Based on the new weathering laws, discussed above, we roughly estimate that the consumption of carbon by silicate weathering will increase by about 10% in the future per degree in global temperature, assuming a 4% increase in runoff per degree in temperature.

Finally, it has been recently demonstrated that the inclusion of the atmospheric CO2 consumption through continental weathering into global models of carbon transport might explain a large portion of the difference between the observed and simulated north–south gradient of atmospheric CO2 [6].

6.2 The impact of emplacement and weathering of basaltic provinces

Taylor and Lasaga [103] have considered the impact of the volcanic rocks on long-term evolution of the geochemical cycles through a study of the Columbia River flood basalts that formed 17–14 Myr ago. Their model is based on the kinetics and thermodynamics of water–rock interactions. The authors have suggested that the important Sr flux resulting from the chemical weathering of Columbia River basalts could explain the inflection in the marine Sr isotope record that occurred in the mid-Miocene [28,65]. This study has confirmed the important weatherability of basaltic rocks, as it was previously shown by several authors [58,75,76]. But it did not take into account the impact of CO2 emission linked to the eruptive onset of the Columbia River basalts on global geochemical cycles, and its subsequent impact on the global biogeochemical cycle through negative climatic feedback loop.

Wallmann [107] has developed a box model to reconstitute the evolution of Cretaceous and Cenozoic climate by including a new parametric law for silicate weathering considering the contribution of basaltic provinces. This model includes five different boxes (carbonate rocks, ocean–atmosphere, particulate organic carbon, oceanic carbonates and Earth's mantle) and calculates the exchange fluxes of carbon, calcium and strontium. The chemical weathering of silicate rocks is separated into two different terms: chemical weathering of young volcanic deposits and other silicate rocks. The first one is a function of the volcanic activity (compilation by [72,73]) and the second a function of physical erosion [14]. Both fluxes are thus heavily dependent on these two forcing functions, and so is the calculated pCO2. It means that the weathering rates of volcanic deposits are equal to zero with a low volcanic activity, similar to the present value. This model emphasises the major impact of basalt weathering on Cretaceous and Cenozoic pCO2 levels. Indeed, during Cretaceous times, pCO2 is enhanced by a factor of more than 2 in the absence of volcanic rock weathering. Finally, Wallmann shows that the volcanic activity acts not only as a major CO2 source, but also creates strong CO2 sinks.

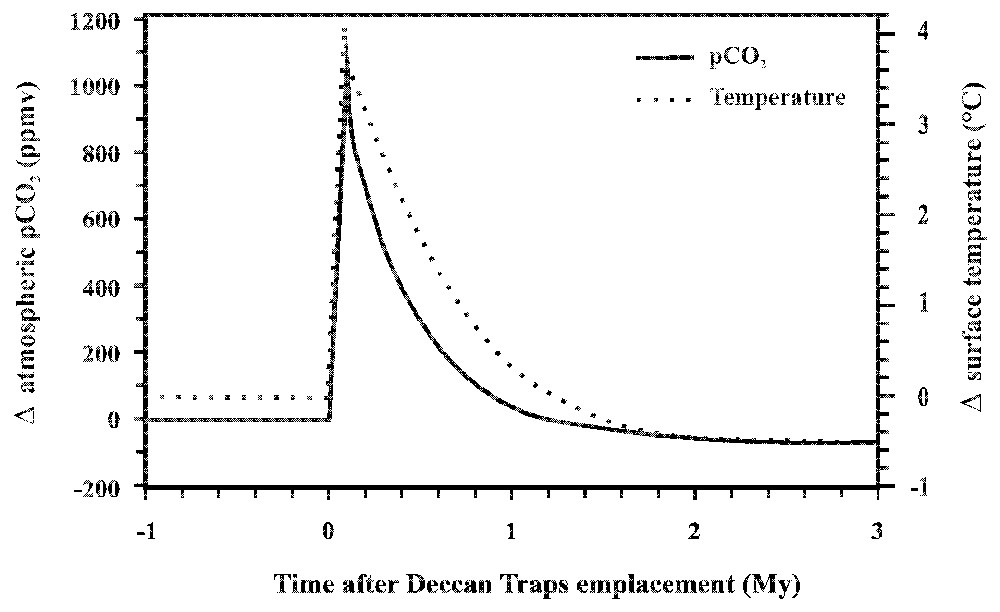

At the same time, we have modelled the impact of Deccan Trapps emplacement at the K-T boundary on the global environment [31]. In contrast with Wallmann [107], the aim of our study was not to reconstruct the long-term evolution of climate in the past, but to quantify precisely the evolution of atmospheric CO2, global surface temperature and Sr isotopic composition of seawater in the direct aftermath of basalt emplacement. Our model is a modified and adapted version of the one developed by François and Walker [47] and describes the geochemical cycles of inorganic carbon, alkalinity and strontium. We have separated the CO2 degassed by the Deccan pulses [68] from CO2 emission from the rest of the world. Similarly, we separated the weathering of the Deccan basalts from the weathering of silicates elsewhere in the world. Moreover, before the emplacement of Deccan basalts, we assumed that this area was constituted by silicates as in the rest of the world and that the global carbon, alkalinity and strontium cycles were at steady state. Using the relationship describing the chemical weathering of basalts as a function of runoff and temperature (see above) and the geochemical analyses of Deccan Trapps rivers, the model shows that emplacement and weathering of Deccan basalts played an important role on the global geochemical cycles. As a result (Fig. 5), Deccan Trapps emplacement is responsible for a strong increase in atmospheric pCO2 by 1050 ppmv, followed by a decrease through enhanced consumption by silicate weathering triggered by global climatic warming, and a new steady state lower than the pre-perturbation level by about 60 ppmv. This result implies that pre-industrial pCO2 would have been 20% higher in the absence of the Deccan Basalts. This pCO2 decrease results from the emplacement of rocks easily weathered, compared to other silicates. This pCO2 evolution is accompanied by a rapid warming of 4 °C coeval with the eruptive phase, followed after 1 Myr by a global cooling of 0.55 °C (Fig. 5). A peak in oceanic 87Sr/86Sr isotopic ratio following Deccan Trapps emplacement is also predicted by the model, with an amplitude and duration comparable to those observed at the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary [79]. This result contradicts Taylor and Lasaga [103], who were expecting a decrease in the 87Sr/86Sr ratio of seawater, triggered by the release of low radiogenic strontium from fresh basaltic surfaces. However, the increase in temperature induced by the eruption of large amount of CO2 into the atmosphere finally increases weathering rates all over the world, resulting in an increase of the delivery of radiogenic strontium into the ocean. We tested the contribution of various parameters such as the duration of the emplacement episode, the pre-Deccan atmospheric pCO2, the contribution of the erosion of carbonates and the dependence of silicate weathering on atmospheric pCO2 [30,31]. All these parameters influenced the system at short time scales (during the first million years) but after 2 Myr, the global evolution of climate is similar, independently from the values adopted for the various parameters. This means that only the surface of basalts and the change in lithology can influence the system on the long term. Recently, Goddéris et al. [59] have proposed that the onset and subsequent weathering of flood basalts in close correlation with the break-up of the Rodinia supercontinent might explain the onset of the Sturtian snowball glaciation. Importantly, most of these flood basalts spread in equatorial region, where temperature and runoff are expected to be highest, enhancing consumption of CO2 through weathering.

Evolution of atmospheric CO2 partial pressure (ppmv) and global surface temperature (°C) calculated by the model during the emplacement of Deccan trapps.

Évolution de la pression partielle de CO2 atmosphérique (ppmv) et de la température globale de surface (°C) calculées par le modèle durant la mise en place des trapps du Deccan.

Overall, the results of this study demonstrate the important control exerted by emplacement and weathering of large basaltic provinces on global environment and show that it cannot be neglected when attempting to improve our understanding of the geochemical and climatic evolution of the Earth.

6.3 Uplift, weathering and carbon cycle

The impact of orogenesis (particularly the Himalayan uplift) on the global carbon cycle and climate has been deeply investigated since the early 90's and the publications by Maureen Raymo and co-authors [95–97]. After more than 10 years of research, the general picture that we have now is rather more complex than the original idea of Raymo. First, the consumption of CO2 by Ca- and Mg-silicate weathering appears to be minor, at least within the Ganges and Brahmapoutra Rivers' catchments, due to the small area of Ca- and Mg-silicate rock outcrops [54]. However, this might be true only for these two rivers. On the other hand, the main sink of carbon due to the Himalayan orogenesis appears to be the burial of organic carbon within the Bengal fan, triggered by high sedimentation rates [44]. Finally, based on modelling studies, Goddéris and François [60] have demonstrated that the existence of a positive global feedback loop between climate cooling and chemical weathering is strongly counteracted by the existence of the negative feedback forcing chemical weathering of silicate to decrease when temperature is decreasing [20,21,106].

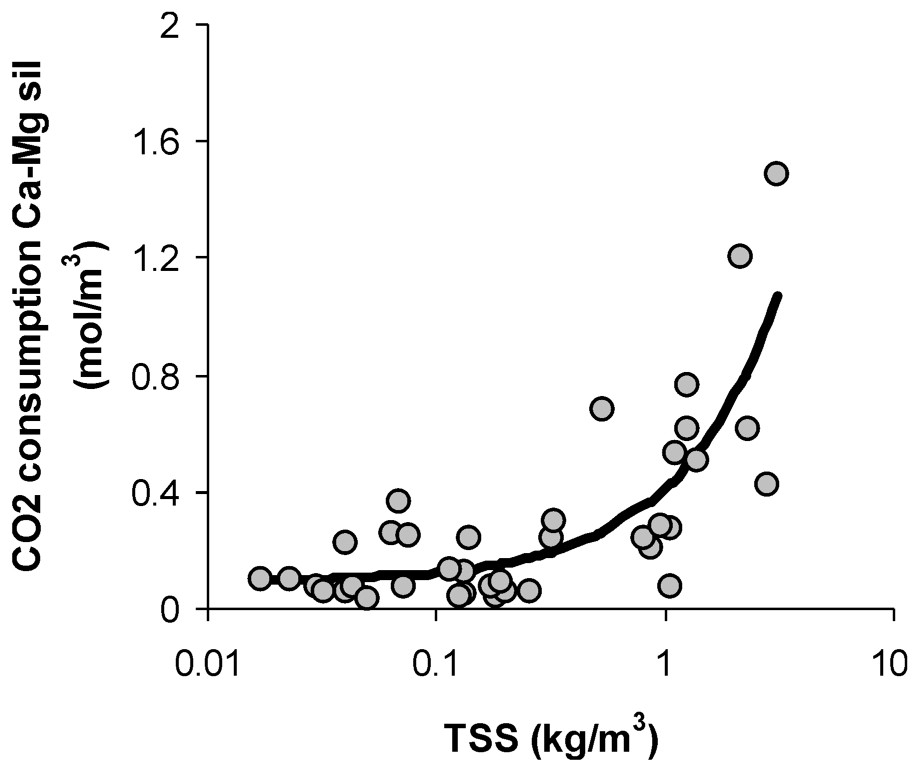

However, the debate is still open. First if we consider all the rivers draining the South-East of Asia, we found an important contribution of the weathering of silicates exposed within this area to the global CO2 consumption. Using the data base of Gaillardet et al. [53], we calculate for this region a CO2 consumption by silicate weathering representing about 35% of the total consumption flux, in spite of the rather small surface (12% of the total continental area). Secondly, as discuss above, the recent works by Gaillardet et al. [53] and Millot et al. [83] have shown a strong relationship (power law) between the flux of particles exported by small and large river catchments and the flux of CO2 consumption by silicate weathering. Such kind of interdependences has been already introduced in various geochemical global models [14,60,71] as follows:

| (2) |

Eq. (2) does not reproduce the field observation, and should be rewritten as follows [83]:

| (3) |

To avoid this climatic catastrophe, we are presently developing a new weathering law for continental granitic lithology. Based on Gaillardet et al. [53] and Millot et al. [83], we emphasize the dependency of chemical weathering on mechanical processes through the following weathering law:

| (4) |

| (5) |

Plot of the CO2 consumption by weathering of continental Ca- and Mg-silicate for the major world river [53], per cube metre, as a function of the concentration of total suspended solids. The bold curve is a linear fit of the data (R2=0.64).

Consommation de CO2 atmosphérique par altération des silicates de calcium et de magnésium pour les principales rivières du monde [53] par mètre cube d'eau, en fonction de la concentration en éléments solides totaux en suspension. La courbe en gras est un fit linéaire des données (R2=0,64).

Importantly, this new law reduces strongly the pure negative climatic feedback on granite weathering, compared to previous relationships (based on Brady [20]). For a fourfold increase in atmospheric CO2, we expect from Eq. (5) a 50% increase in Fsil, while Eq. (2) suggests a 100% increase (assuming a standard greenhouse relationship from Berner [8] and a 4% increase in global runoff per °C, and arbitrarily fixing Fmech to a constant value).

Such type of law still needs verification. However, it should be introduced within global geochemical models, using forcing functions for the mechanical term [80,112]. This result suggests a much more important impact of the weathering of Himalayan silicates than previously expected from modelling studies, since the climatic negative feedback is weaker in agreement with field observations [88]. This allows the pCO2 to fluctuate more in the past, increases the possible impact of mountain uplift on the global carbon cycle and suggests that a non-negligible part of the stabilizing negative feedback might be exerted by basaltic lithology, for which a strong dependence on climate has been established [31,32].

7 Conclusion and perspectives

The aim of this paper is to present a general view on the control of CO2 in the atmosphere and more precisely the role of silicate rock weathering with respect to other sources or sinks (e.g., mantle degassing).

We have summarized the main results obtained recently on small watersheds in high mountains (Pyrenees, France) and in tropical area (Nsimi, Cameroon), on different rivers draining basaltic formations (e.g., Deccan trapps, India), and finally on the main world rivers.

One of the most important results is the demonstration of the importance of chemical weathering of basalts in the global carbon cycle. A simple parametric law is proposed to estimate this flux as a function of continental runoff and temperature. Furthermore, it is shown [31] that the emplacement of fresh basaltic surfaces (such as large igneous provinces LIPs) has two opposite consequences on the global climate. First global temperature is rising as a direct consequence of the intense degassing linked to the eruptive phase. Once the eruptive phase ends, the global climate is getting colder in the aftermath of the magmatic event, as a result of intense weathering of the basaltic surface. A warming and cooling of 4 and 0.5 °C, respectively, have been calculated in the case of Deccan Trapps emplacement [31] and we furthermore propose that one of the Neoproterozoic global glaciations might be the consequence of the onset of several magmatic province in the context of the break-up of the Rodinia supercontinent [59]. The long-term cooling effect is due to the higher weatherability of basalts compared to granite. In the same climatic conditions, basaltic surfaces consumes between 5 to 10 times more atmospheric CO2 than granitic surfaces [32].

The second important result is the confirmation of the temperature effect on the global chemical weathering. This effect has been observed for rivers flowing on basalts but also for the granitic watershed having a high runoff. We thus confirm the regulation of the climate of the Earth by a coupling between climate and weathering, but the negative feedback between climate and granite weathering might be weaker than previously expected. Furthermore, the temperature is not the only mechanism that controls the chemical weathering. Other parameters, like nature and age of the soils, mineralogy and chemistry of granite, and runoff, play a fundamental role that should be further explored. Finally, at the global scale, the fragmentation of continent might be one of the most important process controlling the Earth climate, through the decrease in continentality, leading to increased runoff and consumption of CO2 by silicate weathering. A third generation of global geochemical models should include complex climatic modules (2.5 to 3D models) [34,57]. Such models would allow a better description of the impact of major continental break-up on the global carbon cycle, e.g., consumption of atmospheric CO2 through increased runoff triggered by decreased continentality. This long-term effect has been generally underestimated in the previous modelling work, but might be one of the main controlling factors of the global biogeochemical cycles at the geological timescale. At a shorter timescale, one of the main challenges for the near future will be the development of mechanistic numerical models of weathering processes [102] that can be applied at regional to global scales [66,93], so that the impact of large-scale forcing functions (such as climate change) on weathering can be accurately modelled.

The role of soils is also demonstrated by the relationship that we have found between chemical and physical weathering for large and small rivers [53,83]. As a consequence, we suggest that the formation of mountain ranges plays an important role in the climatic evolution. These new results (without taking into account new developments regarding the degassing rate of the mantle) indicate that explaining the Earth climate evolution with only one parameter (temperature or mountain building) is not realistic. These two parameters cannot be withdrawn, but other parameters such as the emplacement of large basaltic provinces, fragmentation of continents, appearance of vegetation on the Earth have also a very important impact on the climate.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French CNRS, IRD, and INSU programs. We thank also the French Ministry of Education, Research and Technology for funding. We are grateful to all the scientists who helped us on the field, and the technicians in Toulouse and Paris for their support in the different analyses: J. Escalier, R. Freydier, M. Delapart, C. Gorge and M. Valladon. We thank also T. Drever, G. Mégie, R.A. Berner, J. Schott, J.-L. Dandurand, C. France-Lanord, J.-J. Braun, G. Ramstein, Y. Donnadieu, E. Oelkers, S. Brantley, and S. Gislason for helpful discussion during these last years. B. Dupré and J. Gaillardet are particularly grateful towards Claude Allègre, who initiated the program on large rivers in France and helped us to work on this subject.