1 Introduction

Cosmic radiation present at ground level produces cosmogenic nuclides (including 3He, 10Be, 14C, 21Ne, 26Al and 36Cl) within mineral lattices of exposed rock. Their production rates vary with location; cosmic rays are attenuated as they penetrate the atmosphere and deflected by the Earth's magnetic field so production rates are lower at low elevation and low latitudes. In addition, production rates have varied in the past in response to changes in the geomagnetic field strength. In surface rocks, the production rates of most cosmogenic nuclides decrease exponentially with depth, so production is limited essentially to the upper few meters of an exposed rock surface. These in situ produced cosmogenic nuclides are thus useful for dating periods of surface exposure (see reviews in [12,19,31]). Accumulation of cosmogenic nuclides can thus be used to date geological events that exhume material from depth (e.g., glaciation, mass wasting, volcanic activity, and meteor impact). However, once a steady-state balance is reached between production and losses (due to radioactive decay or to erosion of a rock's surface) concentrations and distributions of these nuclides no longer yield geochronological information. At this point they provide both qualitative and quantitative information on physical processes of soil development.

2 Systematics of in situ production of cosmogenic nuclides

Use of cosmogenic nuclides for examination of surficial processes requires a detailed understanding of the production systematics of these nuclides, in particular the variability of their production as a function of subsurface depth. The nuclides most commonly used for studies of surficial environments include 10Be, 26Al and 36Cl (half-lives of 1.5, 0.70 and 0.30 Myr, respectively). Our work has focused on 10Be produced in quartz. Quartz is abundant, easily purified, and easily dissolved for 10Be extraction. In addition, the production mechanisms of 10Be in quartz are simple and well described, making its distributions more readily interpretable.

Beryllium-10 is produced by nuclear reactions induced by three classes of cosmic radiation: neutrons, stopping muons, and fast muons [16,17]. These particles are attenuated as they penetrate into matter, so the production of cosmogenic nuclides may be represented by a combination of exponentials that decrease with depth into rock. As 10Be is essentially immobile after production, its concentration in surficial rock, N (at g−1), can be related to the rock's history of near-surface exposure through Eq. (1):

| (1) |

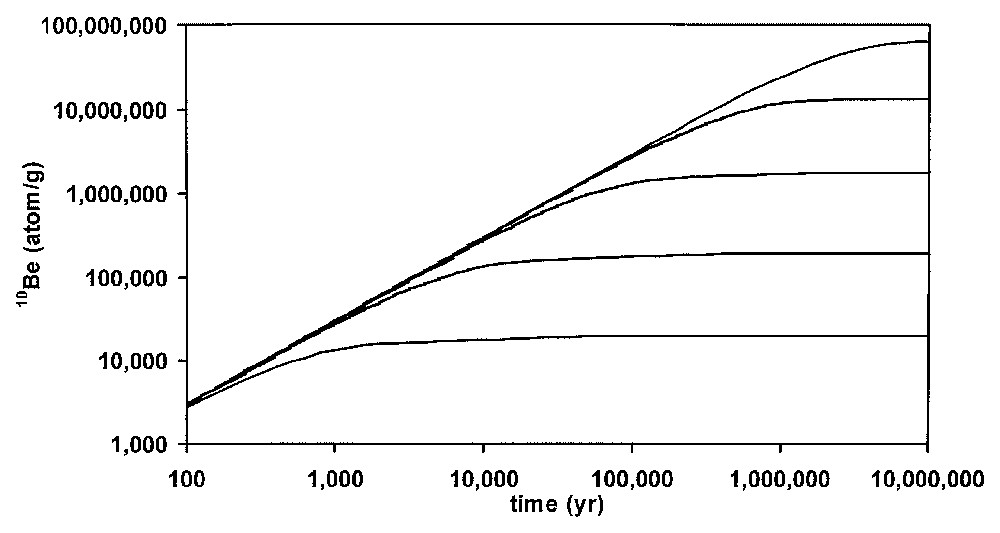

Accumulation of 10Be as a function of surface exposure time and erosion rate. From top to bottom, the curves represent constant erosion rates of 0, 1, 10, 100 and 1000 mm kyr−1. For the case of no erosion, the 10Be concentration increases over time approaching a steady-state balance between production and losses by radioactive decay. At higher rates of erosion, 10Be concentrations reach steady state more rapidly and at lower concentrations. Steady-state concentrations provide only lower limits to the duration of surface exposure.

Accumulation de 10Be en fonction du temps d'exposition de surface et du taux d'érosion. Du haut vers le bas, les courbes représentent des taux constants d'érosion de 0, 1, 10, 100, et 1000 mm ka−1. Dans le cas d'une absence d'érosion, la concentration en 10Be augmente avec le temps en approchant un bilan d'équilibre entre production et pertes par désintégration radioactive. Pour de forts taux d'érosion, les concentrations en 10Be atteignent un état d'équilibre plus rapidement et à de plus faibles concentrations. Les concentrations, à l'équilibre, ne fournissent que des limites inférieures à la durée d'exposition de surface.

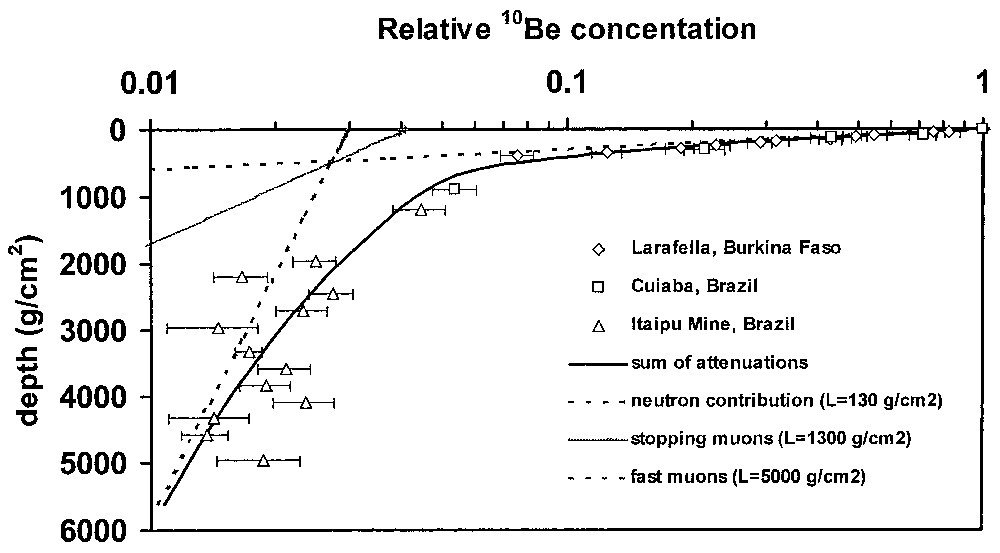

Laboratory- and field-based approaches have been employed to investigate the systematics of cosmogenic nuclide production. Recent laboratory studies involving bombardment of targets by high-energy neutrons, fast muons and stopping muons have provided information on the production of cosmogenic nuclides [16,17]. In combination with measured depth profiles of 10Be in exposed bedrock in tectonically stable environments [3,6,9], these are providing the quantitative description of 10Be production as a function of depth into rock needed as a basis for rigorous application of this approach. These results indicate that neutrons, stopping muons and fast muons account for approximately 98.2, 1.2 and 0.6% of production at the surface, respectively. Depth variability by the three mechanisms can be described as exponential attenuation with e-folding lengths corresponding to approximately 130, 1300 and 5000 g cm−2, respectively (Fig. 2). These results have identified the role of production induced by fast muons at depth, which must be taken into account when evaluating data from soil or rock profiles deeper than 1–2 m. This review applies these new values to a range of approaches used in evaluation of soil development and sediment transport.

Depth profile of 10Be produced by neutrons, stopping muons, and fast muons, with data from outcropping quartz veins in Burkina Faso and Brazil [3,6]. Curves were calculated as described in the text using these field results in combination with experimental data [16,17]. An erosion rate of 1.9 m Myr−1, which yields the observed steady-state surface concentration, was employed. At greater depths, the role of muons becomes increasingly apparent.

Profil en fonction de la profondeur du 10Be produit par des neutrons, des muons à l'arrêt et des muons rapides, avec les données obtenues sur des affleurements de veines de quartz au Burkina Faso et au Brésil [3,6]. Les courbes ont été calculées comme décrit dans le texte, en utilisant les résultats de terrain combinés aux données expérimentales [16,17]. Un taux d'érosion de 1,9 m Ma−1, qui produit la concentration de surface à l'état d'équilibre observé, a été utilisé. Aux plus grandes profondeurs, le rôle des muons devient plus nettement apparent.

3 Applications for evaluation of physical perturbation to rock and soil profiles

Depth profiles of cosmogenic nuclide in soils are uniquely suited for study of a range of processes that generate and destroy soils at geomorphic surfaces. The basic strategy evaluates such processes (e.g., erosion, collapse, burial, bioturbation, soil creep) by examining perturbation of measured depth profiles of cosmogenic nuclide concentrations relative to theoretical profiles expected for a simple undisturbed system. The following sections discuss the effects of each of these physical processes on cosmogenic nuclide accumulation.

3.1 Erosion

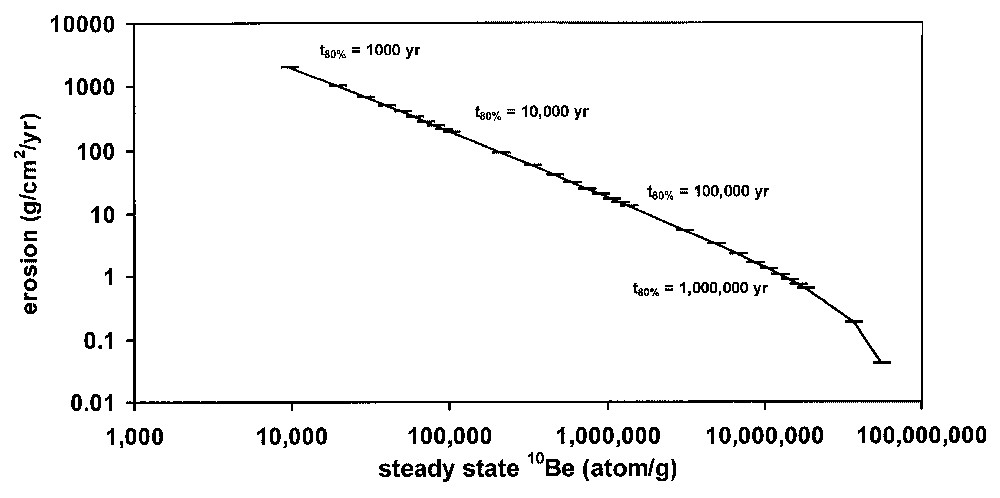

Consider an unrealistic case in which erosion is the only physical process affecting a soil profile; the systematics of cosmogenic nuclide accumulation in such a profile will be identical to that of a profile through exposed bedrock. When independent evidence indicates that a surface has been exposed for sufficient time for the concentration of a cosmogenic nuclide to attain a steady state (such that production is balanced by losses through radioactive decay and erosion) the surface concentration may be used to quantify an average erosion rate (Fig. 1; Eq. (1) for t→∞). The time required to attain steady state depends on the erosion rate; hence the period time represented by the average erosion rate also varies with erosion rate (Fig. 3).

Relationship between steady-state 10Be concentration and average erosion rate. The tick marks represent the time required to achieve 80% of the steady-state concentration, and thus provide an indication of the time period represented by an erosion rate calculated from steady-state 10Be.

Relation entre concentration en 10Be à l'équilibre et taux d'érosion moyen. Les marques représentent le temps requis pour obtenir 80% de la concentration à l'équilibre et ceci fournit une indication sur la période de temps représentée par un taux d'érosion calculé à partir de l'état d'équilibre du 10Be.

The form of a depth profile is also dependent upon erosion rates. At higher erosion rates, a particular bit of rock spends less time in the near-surface zone, leading to a smaller contribution of neutron-produced nuclides. As a consequence, the overall apparent production attenuation length will increase in surfaces undergoing erosion at greater rates. This contrasts with the apparent decrease in cosmic ray attenuation length induced by the processes discussed in the following sections. Variation in depth profiles induced by erosion is subtle compared to the variability of steady-state surface concentrations under differing erosion rates. Nevertheless, it needs to be considered when evaluating the effects of other processes on deep soil profiles.

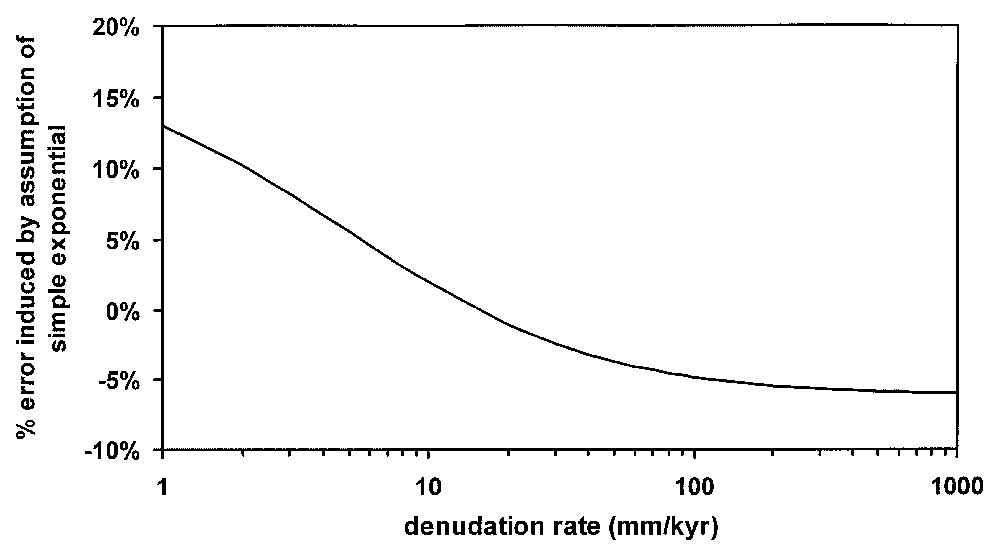

When estimating erosion rates from surface concentrations, a single exponential with an attenuation length of 155 g cm−2 is a reasonable approximation for combined production by the three mechanisms. This may be illustrated through a simple model calculation that compares erosion rates determined from rock surface concentrations under the assumption of a simple exponential decrease in production rate with rates determined with consideration of the three exponentials. This calculation indicates that this simplifying assumption induces relatively small (<13%) errors. In the range of erosion rates typical for most regions on earth (5 to 100 mm kyr−1), these errors are less than ∼5% (Fig. 4).

Error induced in calculated erosion rated due to the assumption of a simple exponential decrease in production rate. Steady-state concentrations were calculated for a range of erosion rates using Eq. (1). Erosion rates were then calculated from these concentrations under the assumption of simple exponential attenuation of 10Be production with an attenuation length of 155 g cm−2, and then compared to the rates employed in the original calculation.

Erreur induite dans le calcul du taux d'érosion, due au fait que l'on admet une simple diminution exponentielle dans le taux de production. Les concentrations à l'équilibre ont été calculées pour une fourchette de taux d'érosion utilisant l'Éq. (1). Les taux d'érosion ont alors été calculés à partir de ces concentrations, en admettant une simple atténuation exponentielle de la production de 10Be avec une longueur d'atténuation de 155 g cm−2, et ont ensuite été comparés à ceux utilisés dans le calcul initial.

This approach can be used to determine landscape scale erosion rates if field evidence suggests that erosion of a sampled outcropping bedrock surface is representative of a wider area. Several studies have thus applied this technique to determine denudation rates for stable cratons with flat topography in a broad range of climate, at sites including the plateau of Mount Roraima, Venezuela [7], southern Sahel of Burkina Faso [3,10], Brazilian tropical forest and savannah [4], Gabon [5], Namibian desert and highlands [1] and Kansas and Missouri, USA (E. Brown, unpublished results). The resultant rates all fall in the range of 3 to 8 m Myr−1. This implies that, on the 105-year timescales recorded by cosmogenic nuclides for this low range of erosion rates, climate does not exert strong control on denudation rates.

3.2 Collapse

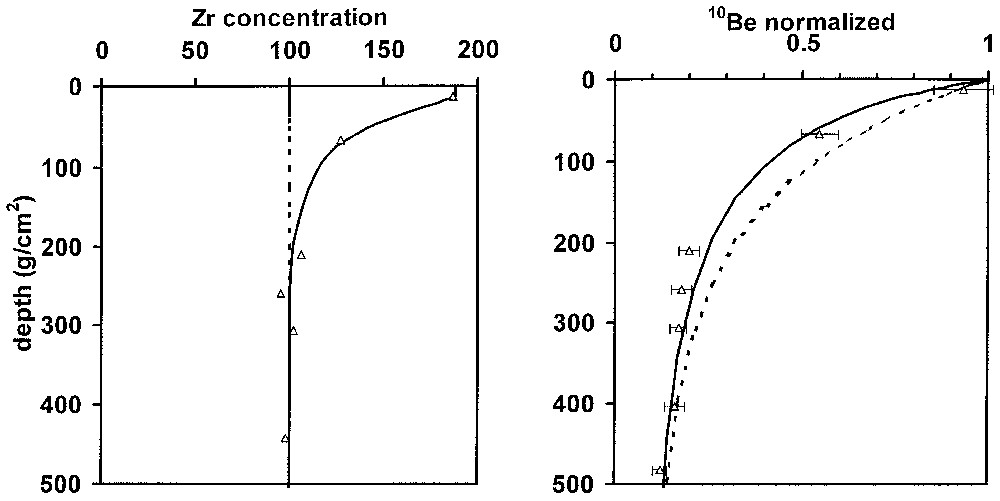

Soil columns are frequently perturbed by collapse – loss of mass from within a soil profile through chemical alteration and loss of volume due to decreased mechanical strength. Collapse has been evaluated under the assumption that elements such as Zr (or Ti) are immobile during chemical weathering and hence have concentrations that increase over time in a given soil [13]. The possibility of mobility of Zr during weathering makes such estimates lower limits on collapse. Comparison of a depth profile of 10Be from a site that has undergone significant collapse with a theoretical profile provides a means, independent of these assumptions of elemental immobility, for examining extent and timing of collapse (Fig. 5). If collapse occurs after most of the 10Be has accumulated, 10Be profiles are compacted by collapse, and the apparent attenuation length of 10Be production is reduced relative to that of an undisturbed system. This apparent decrease in attenuation length contrasts with the apparent increased attenuation lengths associated with erosion. In soil profiles affected by both processes, erosion rates can be evaluated using surface concentrations, and collapse can be constrained by examining deviation from the profile expected for that erosion rate.

Comparison of depth profiles of Zr and 10Be in pre-collapse (dotted line) and post-collapse (solid lines) conditions at the Malemba Hill (Republic of the Congo) [9]. Collapse was calculated under the assumption of Zr immobility during chemical weathering by comparing Zr levels in the deep saprolite with profile samples. The pre-collapse 10Be profile was calculated for an erosion rate of 12 m Myr−1, which yields a steady-state surface concentration comparable to that observed at this site and in nearby ridge crest soils. In the post-collapse 10Be profile sampling depths were adjusted using Zr-based mass loss. The coherence between the collapse indicated by Zr and 10Be shows that collapse occurred after accumulation of the bulk of the 10Be present in the soil.

Comparaison des profils en fonction de la profondeur de Zr et 10Be dans des conditions de pré-affaissement (ligne en pointillé) et post-affaissement (lignes continues) sur la colline de Malemba Hill (république du Congo) [9]. L'affaissement a été calculé en admettant l'immobilité de Zr pendant l'altération chimique par comparaison entre les teneurs en Zr de la saprolite profonde et les échantillons du profil. La courbe de pré-affaissement a été calculée pour un taux d'érosion de 12 m Ma−1, ce qui fournit une concentration de surface à l'équilibre comparable à celle qui a été observée sur ce site et dans des sols d'une arête, au voisinage. Pour la courbe de post-affaissement du 10Be, les profondeurs d'échantillonnage ont été ajustées en utilisant la perte massique basée sur Zr. La cohérence entre l'affaissement indiqué par Zr et par 10Be montre que l'affaissement s'est produit après l'accumulation du total du 10Be présent dans le sol.

This approach is illustrated by a study of soil development at a site near the village of Malemba in the Republic of the Congo—Brazzaville (4°20′S, 12°25′E, 300 m) [3,9] (Fig. 5). At this site, quartz blocks (relicts of a subvertical quartz vein) penetrate through saprolite derived from weathering of Proterozoic schist and soil to outcrop at the summit of a small rounded hill. Measured distributions of 10Be in the quartz blocks show a more rapid decrease in concentration with depth that would be expected for simple exposure and erosion. This reduction in apparent attenuation length is consistent with the collapse calculated under the assumption of Zr immobility, supporting the assumptions implicit in both calculations. Furthermore, as Zr-based estimates of collapse can integrate over longer periods than 10Be-based estimates, the coherence of the results suggest that mass loss occurred relatively recently during the soil's history.

3.3 Burial

Depth profiles of cosmogenic nuclides can provide criteria for understanding whether material has undergone episodic exposure and burial. In static and eroding surfaces, concentrations decrease exponentially with subsurface depth. However, in a surface where material is being deposited, cosmogenic nuclide concentrations will not follow this simple exponential trend [5,8,20]. Accumulation and decay of a cosmogenic radionuclide may be described by Eq. (2):

| (2) |

Quantitative information on burial of previously exposed rock may be obtained from ratios of cosmogenic radionuclides with differing half-lives (for example, 26Al:10Be, with t1/2 of 0.7 and 1.5×106 yr, respectively). In exposed rock, this ratio is dependent on relative production rates of these nuclides, time of exposure, and losses by erosion and by radioactive decay. The ratio 26Al:10Be has a narrow range of possible values (2.8–6.0), which is even more limited (4.8–6.0) in rock surfaces eroding at rates greater than 5 mm kyr−1. However, if material is buried after an episode of surface exposure, radioactive decay can decrease this ratio well below the range observed at the surface. In addition to providing criteria for qualitative determination of whether a sample has undergone extensive periods of burial below the zone of cosmic ray penetration, 26Al:10Be ratios may be used to determine the timing of events that resulted in such burial (e.g., [14]).

3.4 Bioturbation

Bioturbation can have significant impacts on depth distributions of cosmogenic nuclides, bringing material with a near-surface exposure history to greater depth. It does not affect surface concentrations in system at steady state with respect to loss by erosion, but it increases both the time required to reach steady state and the soil column inventory at steady state. Details of these relationships are derived elsewhere [10]. Profiles of 10Be in soils affected by bioturbation are generally constant in the bioturbated zone and have rather sharp decreases in concentration at the base of the reworked zone, returning to an undisturbed exponential profile.

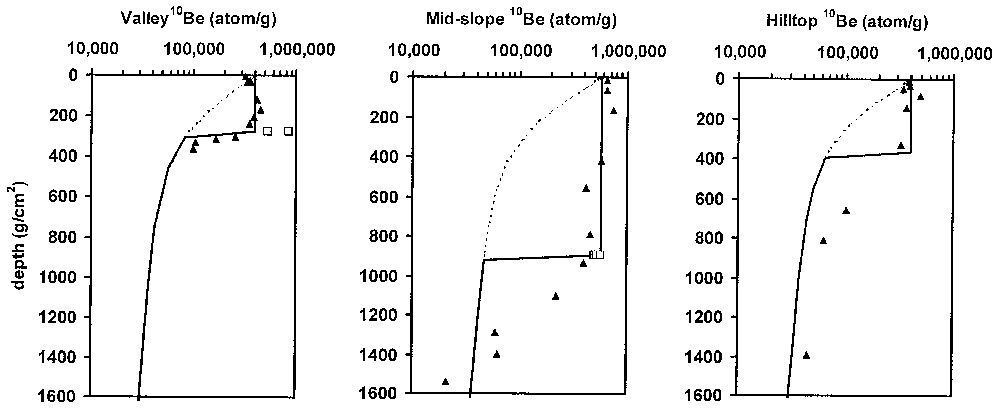

Field studies have demonstrated the response of soil profiles to burial and bioturbation. Profiles of 10Be in quartz sand extracted from soils were determined for the soil sequence at the Goyoum catena in east central Cameroon (5°14′N 13°18′E, 600–700 m) [5]. This site has undergone detailed studies of tropical weathering processes [2,24,25]. A series of sampling pits permit study of soil development at the summit, the slope and at the base of a plateau-like hill. The upper soil horizon at these sites consists of a layer of relatively soft clayey topsoil, which extends to the depth of a nodular layer of indurated Fe-rich nodules and quartz cobbles and pebbles. Below this depth the soils are comprised of weathered saprolite in which the mineral texture of the parent gneissic bedrock is preserved.

Profiles of 10Be are consistent with the role of bioturbation in these soils, but also indicate a possible role of burial of surficial material (Fig. 6). The essentially constant 10Be in the upper soil indicates that homogenization by bioturbation occurs on timescales more rapid than 10Be accumulation. The higher concentrations of 10Be in the upper layer of the mid-slope profile, relative to the hilltop profile, may be the result of exposure while material is transported downslope by soil creep (see Section 3.5). The depth of homogenous 10Be concentrations extends to the indurated nodular layer, below which 10Be distributions revert toward simple exponential decreases. This confirms that bioturbation can mix soils to depths of several meters in tropical environments. The transition toward the exponential decreases in 10Be expected for undisturbed material occurs over a relatively broad depth range, particularly in the mid-slope profile. This could be the result of occasional penetration of bioturbation into the deeper soils or recent accumulation of surface soils that buried materials with an imprint of the near-surface 10Be production by neutrons. The latter scenario is unlikely at hilltop sites, but is not inconsistent with episodes of erosion and burial due to alluvial processes at the base of the hill.

Profiles of 10Be in a series of soil pits (Goyoum, Cameroon) affected by bioturbation. The profiles were taken at the summit, slope and base of a hill. Theoretical profiles for non-bioturbated and bioturbated profiles at steady state are shown as dotted and solid lines. They were calculated using erosion rates that yield average 10Be concentrations in the bioturbated layer. The measured profiles of 10Be in quartz isolated from soils (filled symbols) are consistent with bioturbation to throughout the topsoil, to the depth of the underlying indurated nodular layer. Gravel-sized quartz present at this depth (open symbols) has higher 10Be contents than observed within the soils, suggesting exposure closer to the surface. See text for further discussion.

Courbes de 10Be dans une série de puits pédologiques (Goyoum, Cameroun) affectés par la bioturbation. Les profils ont été prélevés au sommet, sur la pente et à la base de la colline. Les courbes théoriques pour des profils non bioturbés et bioturbés à l'équilibre sont représentées respectivement par les lignes en pointillé et des lignes continues. Elles sont calculées en utilisant des taux d'érosion qui fournissent des concentrations moyennes de 10Be dans l'horizon bioturbé. Les courbes mesurées pour 10Be dans des grains de quartz isolés de sols (symboles pleins) sont cohérentes avec la bioturbation vers (et au sein de) l'horizon supérieur et vers la profondeur de l'horizon nodulaire induré sous-jacent. Le quartz, à la granulométrie de gravier, présent à cette profondeur (symboles ouverts) a des teneurs en 10Be plus élevées que celles observées au sein des sols, ce qui fait supposer une exposition plus proche de la surface. Voir le texte pour une discussion complémentaire.

The quartz cobbles and pebbles at the base of the bioturbated layer in these profiles also provide evidence for exposure closer to the surface. In the profile at the base of the hill the 10Be content of these pebbles is elevated relative to the overlying bioturbated layer, suggesting possible burial. Examination of the ratio of 26Al:10Be in these samples also indicates burial [5], consistent with field observations indicating that this profile is part of an abandoned alluvial system. However, the 26Al:10Be ratio in stoneline samples from the mid-slope profile also suggests burial. Burial of individual clasts does not necessarily require accumulation of material; larger clasts within a developing soil tend to be difficult for bioturbating organisms (e.g., worms, termites) to bring back to the surface.

3.5 Formation of ‘stonelines’ and horizontal displacement

Soil profiles in the humid tropics commonly include ‘stonelines’ – discrete horizons of quartz pebbles and cobbles (see [21] for a discussion). The processes leading to the formation of these features remain poorly understood. A major question to be addressed is whether stonelines result from in situ chemical weathering, are produced by large-scale erosive cycles and physical transport, and/or are formed by physical transport at the scale of the topographical unit.

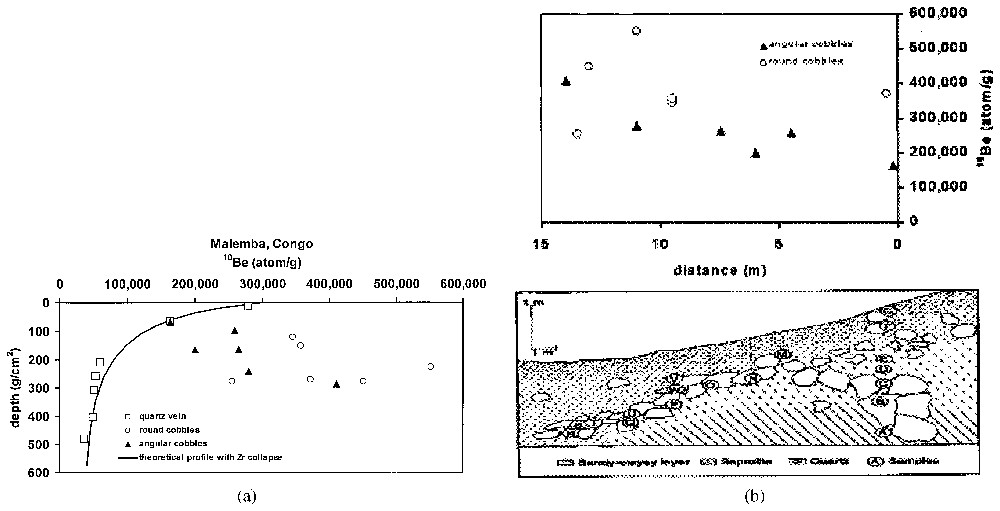

These proposed mechanisms of stoneline formation will lead to distinct depth distributions of in situ-produced cosmogenic nuclides. The utility of cosmogenic nuclides in identifying the origin of stonelines and in quantifying the processes leading to their formation can be illustrated by field examples. At the hill in Malemba, Congo (described in Section 3.2 and shown in Fig. 7) a stoneline extends downslope at the base of a sandy–clayey topsoil. This stoneline is composed of both rounded quartz cobbles and angular quartz clasts. In contrast to the relict quartz vein near the hill's summit, the stoneline material shows no systematic variability in concentration with subsurface depth, and has concentrations far in excess of those observed in the quartz vein (Fig. 7a). When examined as a function of horizontal distance downslope the rounded cobbles still show no systematic variation, but the angular cobbles have 10Be concentrations that increase nearly linearly with downslope distance (Fig. 7b). These observations lead to three qualitative conclusions regarding the formation of this stoneline: (1) clasts within the stoneline has a history of exposure closer to the surface than its present positions; (2) the rounded cobbles are likely to have been exposed elsewhere before deposition and to have an allochthonous origin; (3) the systematic variability in 10Be concentrations in the angular cobbles indicates that they are autochthonous, suggesting that they may result from dismantling and downslope transport (presumably through soil creep) of the outcropping quartz vein (Fig. 7b).

(a) Vertical distribution of 10Be in a stoneline and vein quartz in soils exposed by a road cut (Malemba, Congo [3]). In contrast to the vein quartz, the stoneline clasts show no systematic variability with depth. In addition, their concentrations at any given depth are substantially higher than those of the vein quartz, indicating longer near-surface exposure. (b) Horizontal distribution of 10Be in the Malemba stoneline. The rounded cobbles within the stoneline show no relationship with position within the stoneline, indicating an allochthonous origin. However, the angular clasts show a systematic increase in concentration with distance from the vein quartz outcropping at the hill's summit. This is consistent with an autochthonous origin consisting of dismantlement of the quartz vein followed by downslope movement. The increasing 10Be content of the angular clasts may be used to estimate that downslope creep occurs at a rate of 50–90 m Myr−1.

(a) Distribution verticale de 10Be dans une stoneline et un quartz de veine de sols mis à nu par une tranchée de route (Malemba, Congo [3]). Au contraire des grains de quartz de la veine, les fragments de stoneline ne montrent pas de variabilité systématique avec la profondeur. En outre, leurs concentrations, à n'importe quelle profondeur donnée, sont nettement plus fortes que celles de grains de quartz de la veine, indiquant une plus grande exposition près de la surface. (b) Distribution horizontale de 10Be dans la stoneline de Malemba. Les fragments arrondis au sein de la stoneline ne montrent aucune relation avec leur position dans la stoneline, ce qui indique une origine allochtone. Cependant, les fragments anguleux montrent une augmentation systématique en concentration, au fur et à mesure que l'on s'écarte de l'affleurement de la veine quartzeuse, au sommet de la colline. Ceci est cohérent avec une origine autochtone, consistant en un démantèlement de la veine de quartz, suivi d'un mouvement vers le bas de pente. L'augmentation de la teneur en 10Be des fragments anguleux peut être utilisée pour estimer qu'un fluage en bas de pente s'est produit à une vitesse de 50–90 m Ma−1.

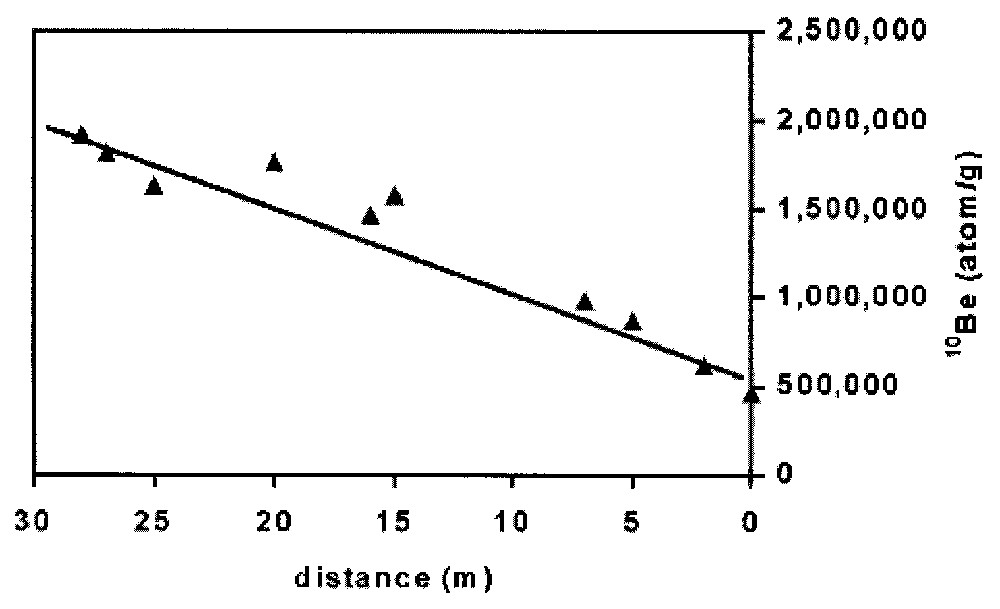

Distributions of cosmogenic nuclides in stoneline clasts also provide a means for quantifying rates of horizontal movement. As stoneline clasts move downslope from an outcropping quartz vein, they undergo further exposure to cosmic rays, and accumulate additional cosmogenic nuclides. Evaluation of the angular clasts in the stoneline at Malemba indicates model creep rates of 50 and 90 m Myr−1. These results are from calculations that assume, respectively, either that each clast remained at a constant depth as it moved downslope or that the subsurface form of the stoneline was constant over time such that each clast moved to progressively greater depths as it moved downslope [3]. If stoneline clasts were closer to the surface than the present stoneline depth, the model rate of downslope movement would be more rapid. This approach has been used in examining stoneline development at other sites, notably at Itaberaba, Brazil, where a very clear increase in concentration with distance from an outcropping quartz vein corresponds to a rate of horizontal movement of ∼65 m Myr−1 [4] (Fig. 8).

Horizontal distribution of 10Be in a stoneline from Itaberaba, Brazil [4]. The systematic increase in 10Be concentration with horizontal distance from a dismantled quartz vein indicates that this vein feeds quartz to the stoneline, which then is subject to downslope creep. Depending upon the assumptions made about depth histories of clasts within the stoneline, 10Be distributions indicate a creep rate of approximately 65 m Myr−1.

Distribution horizontale de 10Be dans une stoneline d'Itaberaba (Brésil) [4]. L'augmentation systématique de la concentration en 10Be au fur et à mesure que l'on s'écarte horizontalement de la veine de quartz démantelée indique que cette veine nourrit en quartz la stoneline, qui est ensuite sujette à un fluage de bas de pente. Si l'on se base sur les hypothèses des histoires en profondeur des fragments de stoneline au sein de celle-ci, les répartitions de 10Be indiquent un taux de fluage d'approximativement 65 m Ma−1.

4 Quantification of basin-scale denudation

Erosion rates determined for discrete bedrock outcrops may be applied to broader areas in cases where there is little spatial variability in erosional conditions (see Section 3.1). However, cosmogenic nuclide accumulation can also be employed for estimating of long-term denudation rates on scales of drainage basins. This is possible because in many cases the cosmogenic nuclide content of sediment discharged by a river represents the average concentration–weighted for area and denudation rate of the various erosional environments present – for the basin as a whole [10,15]. Under such conditions, the following expression (Eq. (3)) may be employed to relate the long-term mean denudation rate of the basin to the measured average concentration 10Be:

| (3) |

A number of studies have compared erosion rates induced from 10Be in sediments with results from other methods. Comparisons with recent river basin mass balances have demonstrated that recent estimates can overestimate long-term (104 to 105 yr) rates in basins where major storms occurred during the period of the mass balance study [10] or where deforestation and conversion to agriculture have affected the basin [11]. In contrast, other studies have shown that long-term denudation rates can exceed modern rates at sites affected by rare catastrophic mass wasting events [18], or enhanced glacial erosion [28,29]. On the other hand, consistency between erosion rates based on cosmogenic nuclides in river sediments and 107-year average sediment removal rates based on fission track analyses has been used to argue for long-term geomorphic stability [1,23].

The roles of tectonics and climate in determining rates of chemical weathering and physical erosion have also been examined in studies that use 10Be in riverine sediment [26,27]. The assumption of immobility of Zr during chemical weathering, in conjunction with 10Be based river basin total erosion rates permitted separation of the effects of chemical and physical weathering in a number of catchments spanning a wide range of erosion rates and climates in the western United States. If Zr is slightly mobile, rather than immobile, the resultant weathering rates will underestimate chemical weathering. Nevertheless, these studies found that chemical weathering rates correlate strongly with physical erosion rates, but that these rates correlate only weakly with climate, implying that climate only weakly regulates non-glacial erosion rates in mountainous granitic terrain.

5 Summary and conclusions

We have much to learn about material transfers at the Earth's surface; cosmogenic nuclides are providing new approaches to quantifying these processes. Recent studies have improved our understanding of production systematics of in situ produced cosmogenic nuclides. In particular, examination of the depth variability of their production has demonstrated the relative roles of neutrons, fast muons and stopping muons in 10Be production. This permits more detailed application of depth profiles of this nuclide to evaluate a range of processes including collapse, erosion, burial, bioturbation, and creep, as well as providing a qualitative basis for distinguishing allochthonous from autochthonous materials. In addition, these nuclides can provide quantitative information on rates of erosion on scales of landforms and drainage basins. These studies can be used to compare modern erosion rates with longer-term values, and have been used in examining the interplay among tectonics, climate and weathering.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. D. Nahon and the organizing committee for providing the opportunity to participate in this thought-provoking symposium. This manuscript benefited from thoughtful reviews by M. Pavich and M. Velbel.