Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

C'est dans les années 1960–1970, que la localité fossilifère de Fort Ternan au Kenya (Fig. 1) est devenue célèbre, grâce à sa faune riche et diversifiée et surtout à la présence d'un hominoïde que certains chercheurs considéraient, à l'époque, comme le plus ancien hominidé bipède, capable d'utiliser des outils [11–13]. Fort Ternan est la localité-type de Kenyapithecus wickeri, dont la synonymie avec le genre indien Ramapithecus a été fortement débattue [12,13,26–28,33,34,36]. Il s'avéra que les deux genres étaient bien distincts [18,19] et que Kenyapithecus n'était pas un hominidé, mais bien un grand singe à dimorphisme sexuel fort. Les caractères morphologiques supposés « hominidés » (face courte, petite canine, présence d'une fosse canine, forme parabolique de l'arcade dentaire) étaient mal décrits, ou étaient des caractères de femelle du spécimen-type. Enfin, les outils « supposés » se sont avérés être des pierres anguleuses provenant d'un lahar qui surmonte les paléosols fossilifères [22].

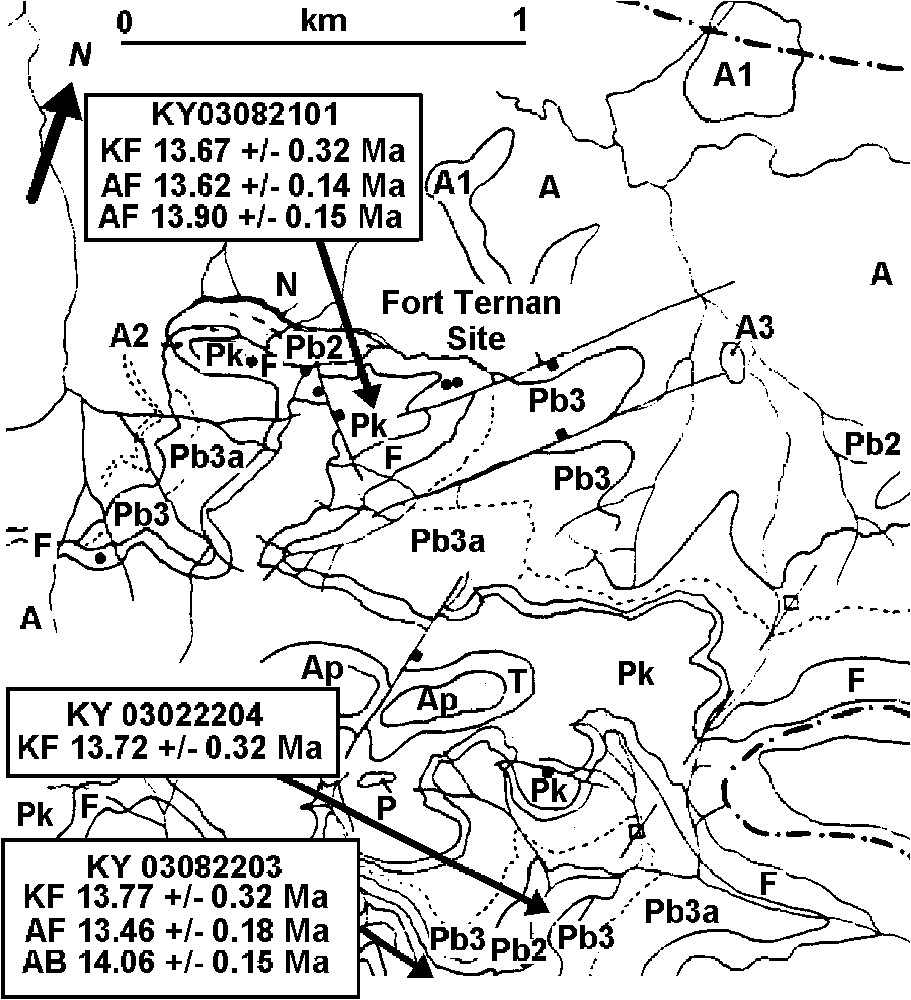

Geological map of the Fort Ternan area [20], showing sampling localities: Ap, polymict agglomerate; T, tunnel tuff; Pk, Kericho phonolite; F, Fort Ternan beds; Pb3a, Baraget phonolite (weathered); Pb3, Baraget phonolite (fresh); Pb2, biotite, glassy and autobrecciated phonolite; Pb1, pink sanidine tuff; N, regolith beneath Kericho phonolites; A3, zeolitised basanite; A2, olivine nephelinite; A1, aegerine basanite; A, Kapurtay and Cliff agglomerate (AB = 40Ar/39Ar determination on biotite; AF = 40Ar/39Ar determination on feldspar; KF = K/Ar determination on feldspar). (The dates are given to two decimal places: in the text these are rendered to one decimal place.) Masquer

Geological map of the Fort Ternan area [20], showing sampling localities: Ap, polymict agglomerate; T, tunnel tuff; Pk, Kericho phonolite; F, Fort Ternan beds; Pb3a, Baraget phonolite (weathered); Pb3, Baraget phonolite (fresh); Pb2, biotite, glassy and autobrecciated phonolite; Pb1, ... Lire la suite

Carte géologique de la région de Fort Ternan [20] avec les localités échantillonnées : Ap, agglomérat hétérogène ; T, Tunnel Tuff ; Pk, phonolite de Kericho ; F, couches de Fort Ternan ; Pb3a, phonolite de Baraget (altérée) ; Pb3, phonolite de Baraget (fraîche) ; Pb2, Biotite, phonolite vitreuse et autobréchifiée ; Pb1, cinérite à sanidine rose ; N, régolithe sous les phonolites de Kericho ; A3, basanite zéolitisée ; A2, néphélinite à olivine ; A1, basanite à ægyrine ; A, agglomérats de Kapurtay et de Cliff (AB = détermination 40Ar/39Ar sur biotite ; AF = 40Ar/39Ar sur feldspaths ; KF = détermination K/Ar sur feldspaths). (NB : Les âges sont calculés avec deux chiffres après la virgule, alors que, dans le texte, ils sont arrondis au premier chiffre après la virgule.) Masquer

Carte géologique de la région de Fort Ternan [20] avec les localités échantillonnées : Ap, agglomérat hétérogène ; T, Tunnel Tuff ; Pk, phonolite de Kericho ; F, couches de Fort Ternan ; Pb3a, phonolite de Baraget (altérée) ; ... Lire la suite

Malgré son exclusion de la famille des Hominidae (sensu stricto), Kenyapithecus demeure un hominoïde intéressant [32,36], qui pourrait avoir donné naissance aux hominidés bipèdes ultérieurs [30]. C'est pourquoi, la précision de l'âge des dépôts dont il provient est importante.

L'âge des niveaux fossilifères de Fort Ternan a été estimé à 14 Ma par Bishop et al. [2] à partir des analyses isotopiques des cristaux de biotite provenant des sédiments fossilifères (sur l'échantillon MB 15, les âges obtenus étaient de

Les analyses des faunes de la formation de Ngorora (fin du Miocène moyen) au Kenya [17,19], dont l'âge varie de 13 Ma environ à la base (membre A) jusqu'à 10,5 Ma au sommet (membre E) [5], montrent que de nombreux mammifères des membres A–D de cette formation étaient proches ou identiques à ceux de Fort Ternan, malgré la différence de 2 Ma estimée entre les deux (Tableau 1). Une stase évolutive aussi longue paraît improbable et l'un d'entre nous (MP) [23,24] estimait que l'âge isotopique de 14 Ma calculé pour ce dernier gisement était trop vieux. Il était donc intéressant de ré-échantillonner la coupe pour préciser l'âge des sédiments fossilifères.

Large mammal faunas from Fort Ternan and Ngorora (Members A–D) omitting indeterminate genera. Note the large number of species that occur at both sites

Faunes de grands mammifères de Fort Ternan et de Ngorora (Membres A–D). Noter le grand nombre d'espèces communes entre les deux sites. (Les genres indéterminés n'ont pas été mentionnés)

| Fort Ternan Beds only | Both Fort Ternan and Ngorora | Ngorora Members A–D only |

| Kenyapithecus wickeri | Simiolus sp. | Victoriapithecus sp.⁎ |

| Proconsul sp.? | Hyainailourus sulzeri | Otavipithecus or Kenyapithecus? |

| Rangwapithecus sp. | Percrocuta tobieni | Dryopithecus sp? |

| Oiocerus tanycerus | Agnotherium antiquum | Dissopsalis pyroclasticus ⁎ |

| Butleria rusingense | Orycteropus chemeldoi | Eomellivora sp. |

| Afrochoerodon sp. | Sivaonyx sp. | |

| Deinotherium giganteum | Gomphotherium sp. | |

| Chilotheridium pattersoni | Choerolophodon pygmaeus ⁎ | |

| Paradiceros mukirii | Tetralophodon sp. | |

| Listriodon bartulensis | Parapliohyrax tugenensis | |

| Albanohyus sp. | Aceratherium acutirostratum ⁎ | |

| Kenyapotamus ternani | Brachypotherium sp.⁎ | |

| Dorcatherium chappuisi | Lopholistriodon kidogosana | |

| Dorcatherium piggoti | Homoiodorcas tugenium | |

| Climacoceras gentryi | ||

| Palaeotragus primaevus | ||

| Samotherium africanum | ||

| Kipsigicerus labidotus | ||

| Gentrytragus gentryi | ||

| Gazella sp. |

⁎ Taxa from Ngorora that are known to occur in deposits older than Fort Ternan. Their absence from the latter site is probably due to differences in palaeoecology between Ngorora and Fort Ternan.

2 Datations K/Ar et 40Ar/39Ar : échantillons et préparation des échantillons

Dans la gorge de Kipchorion, immédiatement au sud de Fort Ternan (Figs. 1 et 2), ont été prélevés des échantillons orientés qui proviennent de cinq coulées de laves formant les Lower Kericho Phonolites, sous-jacentes aux couches de Fort Ternan [16,17,20,21]. Un autre échantillon orienté a été récolté au sommet de la colline dans l'Upper Kericho Phonolite, directement au-dessus des niveaux fossilifères. Des datations K/Ar et 40Ar/39Ar ont été réalisées (Tableau 2). Après examen en lame mince, trois échantillons très frais ont été conservés pour les datations K/Ar : deux provenant des niveaux inférieurs et un du niveau supérieur :

- • (1) KY03082203 : phonolite sous le niveau fossilifère ;

- • (2) KY03082204 : phonolite sous le niveau fossilifère ;

- • (3) KY03082101 : phonolite au-dessus du niveau fossilifère.

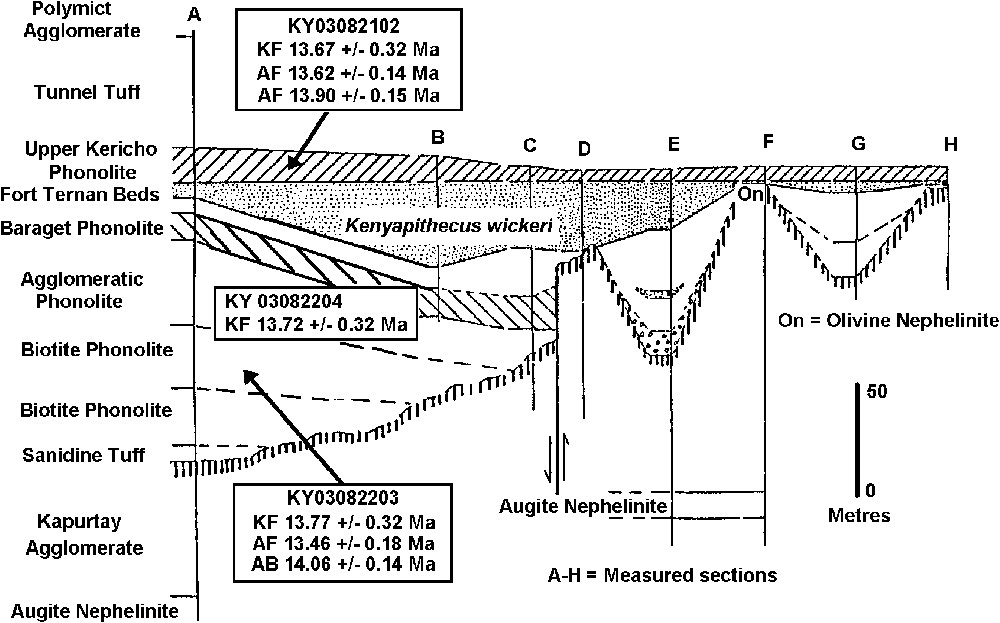

Stratigraphy of the Fort Ternan area [20] showing positions of samples. A–H, measured sections in different sectors of the Fort Ternan area (the main fossil beds are in section C). The vertical hatching denotes the unconformity between the Kapurtay Agglomerates below and the Kericho Phonolites above. (AB = 40Ar/39Ar determination on biotite; AF = 40Ar/39Ar determination on feldspar; KF = K/Ar determination on feldspar.) (The dates are given to two decimal places: in the text these are rendered to one decimal place.) Masquer

Stratigraphy of the Fort Ternan area [20] showing positions of samples. A–H, measured sections in different sectors of the Fort Ternan area (the main fossil beds are in section C). The vertical hatching denotes the unconformity between the Kapurtay ... Lire la suite

Stratigraphie de la région de Fort Ternan [20] avec la localisation des échantillons. A–H, sections mesurées dans différents secteurs de la région de Fort Ternan (les principaux niveaux fossilifères sont situés dans la section C). Les hachures verticales soulignent la discordance entre l'agglomérat de Kapurtay à la base et les phonolites de Kericho au-dessus. (AB = détermination 40Ar/39Ar sur biotite ; AF = détermination 40Ar/39Ar sur feldspaths ; KF = détermination K/Ar sur feldspaths.) (NB : Les âges sont calculés avec deux chiffres après la virgule, alors que dans le texte, ils sont arrondis au premier chiffre après la virgule.) Masquer

Stratigraphie de la région de Fort Ternan [20] avec la localisation des échantillons. A–H, sections mesurées dans différents secteurs de la région de Fort Ternan (les principaux niveaux fossilifères sont situés dans la section C). Les hachures verticales soulignent ... Lire la suite

Isotopic age determinations of samples of lava flows in the vicinity of Fort Ternan, Western Kenya. The Fort Ternan fossiliferous beds lie between the Lower and Upper Kericho phonolites

Déterminations des âges isotopiques des échantillons de laves à proximité de Fort Ternan, Kenya occidental. Les niveaux fossilifères de Fort Ternan sont situés entre les phonolites inférieure et supérieure de Kericho

| Sample No. | Locality | Stratigraphic position | Rock type | Material analysed | K (wt%) | Radiogenic 40 Ar 10 −8 ccSTP/g | Non-radiogenic Ar% | K/Ar age Ma |

| KY 03082101 | Fort Ternan | Upper Kericho Phonolite above Fort Ternan Beds | phonolite lava | anorthoclase | 6.47±0.13 | 344.4±4.2 | 6.4 | 13.7±0.3 |

| KY 0308205 | Fort Ternan | Lower Kericho Phonolite below Fort Ternan Beds | phonolite lava | |||||

| KY 03082204 | Fort Ternan | Lower Kericho Phonolite below Fort Ternan Beds | phonolite lava | anorthoclase | 5.49±0.11 | 293.6±3.7 | 8.3 | 13.7±0.3 |

| KY 03082203 | Fort Ternan | Lower Kericho Phonolite below Fort Ternan Beds | phonolite lava | anorthoclase | 5.52±0.11 | 296.1±3.7 | 6.8 | 13.8±0.3 |

| KY 03082202 | Fort Ternan | Lower Kericho Phonolite below Fort Ternan Beds | phonolite lava | |||||

| KY 03082201 | Fort Ternan | Lower Kericho Phonolite below Fort Ternan Beds | phonolite lava |

KY03082203 et KY03082101 sont hautement porphyriques et KY03082204, peu porphyrique, est composé de phénocristaux d'anorthose (pouvant atteindre 11 mm de long), de néphéline, de biotite, d'augite, d'apatite et de magnétite baignant dans une matrice formée de feldspaths, de pyroxènes monocliniques, d'aegyrine, d'apatite, de magnétite et de verre dévitrifié. Après préparation (voir version anglaise pour davantage de détails), l'anorthose a été conservée pour les datations K/Ar, ainsi que des échantillons frais d'anorthose en gros grains et de biotite (de 1 à 2 mm de diamètre) pour la datation 40Ar/39Ar.

3 Protocole d'analyse et estimations des âges K/Ar et 40Ar/39Ar

Pour le protocole d'analyse et le calcul des âges et des erreurs, la méthode décrite par Nagao et al. [14] et Itaya et al. [9] a été employée.

Les âges K/Ar (Tableau 2) calculés sur l'anorthose des coulées de phonolite KY03082203, KY03082204 et KY03082101 sont tous de

40Ar/39Ar age determinations of feldspar and biotite from lavas in the Fort Ternan area, and comparison with K/Ar age determinations from the same rock samples (Fig. 3)

Détermination des âges 40Ar/39Ar des feldspaths et des biotites des laves de la région de Fort Ternan, et comparaison avec les âges K/Ar estimés à partir des mêmes échantillons de roches (Fig. 3)

| Sample No. | Locality | Rock type | Material | K/Ar | 40Ar/39Ar | Remarks |

| KY03082101 Feld | Fort Ternan | phonolite | anorthoclase | 13.7±0.3 | 13.6±0.1 | |

| KY03082101 Feld | Fort Ternan | phonolite | anorthoclase | 13.7±0.3 | 13.9±0.2 | Second step age |

| KY03082101 B1 | Fort Ternan | phonolite | biotite | – | 13.2±0.2 | Plateau |

| KY03082101 B2 | Fort Ternan | phonolite | biotite | – | 14.5±0.2 | |

| KY03082203 B1 | Fort Ternan | phonolite | biotite | – | 14.1±0.1 | Plateau |

| KY03082203 F1 | Fort Ternan | phonolite | anorthoclase | 13.8±0.3 | 13.5±0.2 | Second step age |

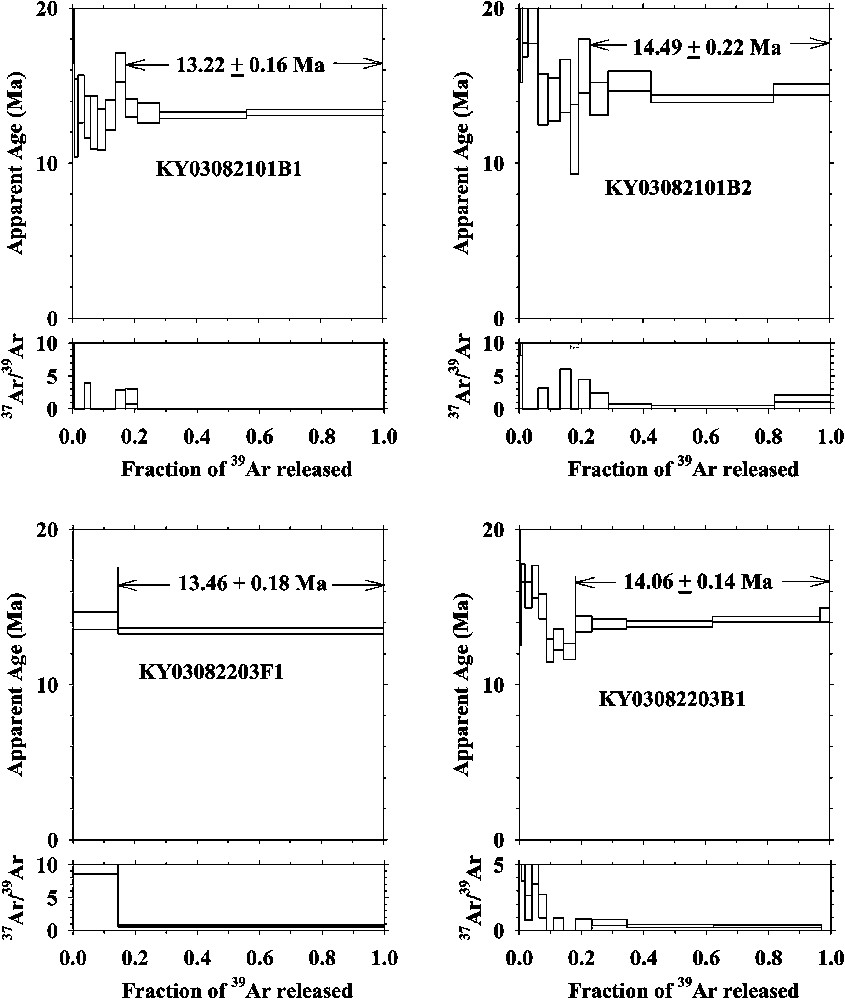

Age spectra and 37ArCa/39ArK ratios of samples from the Fort Ternan area, western Kenya and correlation plots of biotite samples. (The dates are given to two decimal places: in the text these are rendered to one decimal place.)

Spectre des âges et rapports 37ArCa/39ArK des échantillons de la région de Fort Ternan, Kenya occidental et tracés des corrélations des échantillons de biotite. (NB : Les âges sont calculés avec deux chiffres après la virgule, alors que, dans le texte, ils sont arrondis au premier chiffre après la virgule.)

Deux âges calculés sur deux cristaux de biotite du même échantillon (KY03082101) sont très différents, avec une forte discordance au-delà des marges d'erreur. De plus, les deux montrent un enrichissement en 40Ar dans les basses températures, suggérant la présence d'un excès d'argon dans l'environnement pendant la cristallisation. Une tendance similaire est observée dans les spectres d'âges obtenus pour l'anorthose aux basses températures. Un des âges obtenu pour la biotite est même plus jeune que ceux de l'anorthose, ce qui est contraire à l'ordre de refroidissement. Ces âges ont probablement été perturbés par un ou plusieurs événements ultérieurs.

4 Discussion des âges K/Ar

Certains coulées de laves de la Lower Kericho Phonolite [17,20] sont trop altérées pour donner des âges K/Ar fiables. La quatrième coulée de la base de la séquence (Fig. 2), qui est une phonolite massive à biotite–anorthose, a livré un âge de

5 Discussion des âges 40Ar/39Ar

Si on tient compte des marges d'erreurs, les résultats des analyses 40Ar/39Ar des feldspaths s'accordent assez bien avec ceux obtenus sur les échantillons testés pour K/Ar. En revanche, l'âge calculé à partir de la biotite de l'échantillon KY03082101 (situé au-dessus des couches de Fort Ternan),

6 Corrélations intercontinentales

L'échelle biochronologique est-africaine, calibrée en de nombreux points par des âges isotopiques, a été utilisée pour proposer des corrélations avec les zonations mammaliennes européennes (zones MN) (par exemple, [10,24], parmi d'autres). Bien qu'il y ait un débat dans la littérature, il est souvent admis que la faune de Sansan (France), niveau repère pour MN 6, est corrélée avec celle de Fort Ternan. Sen [31] a corrélé cette faune avec la zone de polarité normale C5Bn.2n, qui, selon l'échelle de référence (GPTS) de Baksi [1], donnerait un âge de 16,2 à 16,3 Ma pour Sansan, ce qui paraît trop vieux [23]. Daams et al. [4], ont corrélé la même section à la zone normale C5ABn qui, sur le même GPTS, lui accorderait un âge de 14,0 à 14,3 Ma. Pickford [23] estime que la section pourrait également être corrélée à la zone C5Ar.2n, ce qui donnerait alors un âge de 13,3 à 13,4 Ma, en utilisant l'échelle GPTS de Baksi [1]. En revanche, si les calculs sont basés sur d'autres échelles GPTS [3], les niveaux de Sansan pourraient être datés de 15,0 à 15,1 Ma [31], 13,3 à 13,5 Ma [4] ou même de 12,8 Ma [37]. (NB : Dans les articles cités, les âges sont donnés avec deux chiffres après la virgule, alors qu'ici ils sont arrondis au premier chiffre après le virgule.)

Les corrélations fauniques proposées par Pickford et Morales [24], combinées aux âges isotopiques et à la stratigraphie paléomagnétique, suggèrent que l'échelle internationale la plus fiable, au moins pour cette partie du Miocène, serait celle de Baksi [1].

7 Discussion

Les dépôts fossilifères de Fort Ternan ont livré une faune importante du Miocène moyen, sur laquelle le Faunal Set IV de la zonation faunique est-africaine a été défini [16]. Bien que les dépôts aient été initialement considérés comme pliocènes (au vieux sens du terme) [11], il est apparu rapidement qu'ils étaient probablement plus anciens [2]. Les estimations initiales basées sur des cristaux de biotite contenus dans les niveaux fossilifères suggéraient un âge de 14 Ma, corroboré ultérieurement [33], en dépit du fait que la coulée de lave surmontée par les mêmes sédiments ait donné un âge plus jeune que 14 Ma. Il avait été proposé que l'horloge isotopique de la lave ait été affectée par la chaleur produite par un lahar qui surmonte les couches de Fort Ternan. Le problème réside dans le fait que les biotites intrasédimentaires n'avaient pas été affectées, alors que les anorthoses de la coulée sous-jacente, bien plus éloignée du lahar, l'étaient. Par ailleurs, l'anorthose étant plus réfractaire que la biotite, elle est donc plus difficile à altérer.

Les faunes du Miocène moyen de la formation de Ngorora (membres B–D) au Kenya, âgées de 13 à 12 Ma [5] et celle de Fort Ternan partagent un certain nombre de taxons [15,20] (Tableau 1). Les similitudes entre ces faunes suggèrent qu'elles sont plus proches chronologiquement que ne l'indiquaient les âges isotopiques. Si ces derniers étaient corrects, il fallait admettre que les faunes n'avaient que peu, voire pas évolué pendant 1 à 2 Ma. Bien qu'une stase évolutive sur une telle période de temps soit théoriquement possible, elle reste à démontrer.

Le ré-échantillonnage et l'analyse de la succession complète des coulées de lave sous-jacentes aux couches de Fort Ternan montrent que ces dernières sont probablement plus jeunes que 14 Ma. Deux des six coulées sous-jacentes aux sédiments ont livré un âge de

1 Introduction

The fossiliferous locality of Fort Ternan, Kenya (Fig. 1), rose to prominence during the 1960's and 1970's on account of its rich and diverse fauna which included what was at the time considered by some researchers to be the earliest known remains of bipedal, tool-using hominids which were thought to have lived in communities with social organisations close to those of extant humans [11–13]. It is the type locality of the genus and species Kenyapithecus wickeri around which a controversy developed [12,13,26–28,33,34,36]. The thrust of the debate concerned its synonymy or otherwise with the Indian genus Ramapithecus. What was generally agreed by the proponents of this debate was that Kenyapithecus/Ramapithecus was a hominid in the strict sense of the term (various features of the face and dentition, tool use, community living, postulated bipedal locomotion). This debate was finally settled by Pickford [18,19] in favour of the distinctiveness of Kenyapithecus as a genus separate from Ramapithecus, but it was removed from Hominidae and returned to the great apes, on account of its strongly dimorphic nature. The supposed hominid-like morphological features (short face, small canine, presence of canine fossa, dental arcade shape) [36] were either inaccurately reported, or are due to the female status of the type specimen and referred material. Throughout the debate, male hominoid specimens from the same site were excluded from Kenyapithecus and classified as Proconsul, despite significant differences from the latter genus. The supposed stone tools from the site were shown to be angular chunks of volcanic rock derived from a lahar that overlies the fossiliferous palaeosols [22]. The case for community living and bipedal locomotion was weak, and it is still that way.

Despite the exclusion of Kenyapithecus from the family Hominidae (sensu stricto), it remains an interesting hominoid which could have given rise, in the fullness of time, to bipedal hominids [32]. For this, and other reasons, refinement of the age of the deposits from which it was excavated, is important.

The fossil beds at Fort Ternan were first estimated to be 14 Ma by Bishop et al. [2] on the basis of isotopic analyses of biotite crystals obtained from the sediments which yield the fossils (age determinations (sample MB 15) were

Meanwhile analyses of faunas from the late Middle Miocene of Kenya, in particular those from the Ngorora Formation [17,19], which ranges in age from ca 13 Ma at the base (Member A) to 10.5 Ma at the top (Member E) [5], revealed that many of the mammals from Members A–D of the Ngorora Formation were close to or identical to those from Fort Ternan, in spite of the supposed differences in age of up to 2 Myr (Table 1). Faunal evolutionary stasis over such a lengthy time period is unlikely, and Pickford [23,24] has tended to consider that the isotopic age of 14 Ma for Fort Ternan is too great. Clearly, however, in order to avoid circular reasoning, it was necessary to resample the entire succession of strata in the region of Fort Ternan so as to refine the age determination of the fossiliferous sediments.

2 K/Ar and 40Ar /39Ar dating

2.1 Sample description and preparation

Oriented samples from five lava flows mapped as Lower Kericho Phonolites, which underlie the Fort Ternan Beds [16,17,20,21], were collected from Kipchorion Gorge, immediately south of Fort Ternan (Figs. 1 and 2). In addition, an oriented sample of the Upper Kericho Phonolite was collected from the hilltop directly above the fossiliferous beds. These were analysed for K/Ar and 40Ar/39Ar (Table 2). The following three samples were suitable for K/Ar age determination:

- • (1) KY03082203: phonolite lava below a fossil layer;

- • (2) KY03082204 phonolite lava below a fossil layer;

- • (3) KY03082101 phonolite lava above a fossil layer.

These lava samples are very fresh. KY03082203 and KY03082101 are highly porphyritic, and KY03082204 is sparsely porphyritic, and consists of phenocrysts of anorthoclase (up to 11 mm in length), nepheline, biotite, augite, apatite and magnetite with a ground mass of feldspar, clinopyroxene, aegirine, apatite, magnetite and devitrified glass. Samples of anorthoclase for K/Ar age determination were prepared by crushing and sieving. Anorthoclase phenocrysts of 423–254 μm were sieved. The sieved fraction was cleaned in water, then dried in an oven at 110 °C. The magnetic minerals were removed manually by magnet. The anorthoclase grains were removed from the sieved samples by a Frantz isodynamic separator, heavy liquid (bromoform) and additional handpicking. The separated minerals were ultrasonically washed several times in ethanol and ion exchange water for 10 min. The separated anorthoclase samples were leached two or three times in HCl solutions (HCl:H2O = 1:4) for 15 min in order to remove any argillaceous alteration products. A portion of the fraction was ground by hand in an agate mortar, and used for potassium analysis.

Fresh coarse-grained anorthoclase and biotite samples (1–2 mm in diameter) for 40Ar/39Ar age determination were separated by handpicking under a microscope.

2.2 Analytical procedure and results of K/Ar and 40Ar/39Ar age determinations

Analytical procedures for potassium and argon and calculations of ages and errors were based on the method described by Nagao et al. [14] and Itaya et al. [9]. Potassium was analyzed by flame photometry using a 2000 ppm Cs buffer and has an analytical error of less than 2% at

The results of K/Ar age determinations are shown in Table 2. The anorthoclase K/Ar ages from phonolite lava flows KY03082203, KY03082204 and KY03082101 are

Individual mineral grains (0.3–1 mm in size) were placed in 2-mm holes on an aluminium tray. Neutron flux and interference factors were monitored by age standard grains (3 g hornblende; [29]), and calcium (CaSi2) and potassium (synthetic KAlSi3O8 glass) salts for Ca and K corrections. Subsequently the tray was vacuum-sealed in a quartz tube. Neutron irradiation of the sample was carried out in the core of the 5-MW Research Reactor at Kyoto University (KUR) for 5 h. The fast neutron flux density is confirmed to be uniform in the dimension of the sample holder as little variation in J-values of the evenly spaced age standards was observed [6].

A mineral grain was analyzed by step-heating technique using a 5-W continuous argon ion laser. Temperatures of samples were monitored by an infrared thermometer with a precision of 3 °C in an area of 0.3-mm diameter [7]. Each crystal was heated under a defocused laser beam at a given temperature for 30 s. The extracted gas was purified with a SAES ZrAl getter (St 101) kept at 400 °C for 5 min. Argon isotopes were measured using the custom-made mass spectrometer with a high resolution

Two ages of single crystal biotite grains from the same sample (KY03082101) differ greatly from each other, not even agreeing within their analytical uncertainties. Furthermore, both show a gain of 40Ar in the low-temperature fractions, suggesting some post-eruptive excess argon. A similar age trend in low temperatures is also seen in the anorthoclase age spectra. One of the biotite ages is even younger than the anorthoclase ages, disagreeing in the order of temperature closure (Table 3). These biotite ages may have been disturbed by a later event, resulting in the age variation. We adopt cooling ages of the minerals as 14.0 Ma for biotite and 13.7 Ma for anorthoclase.

2.3 Discussion of age determinations

2.3.1 K/Ar age determinations

The basal flows of Lower Kericho Phonolite [17,20] are too altered to yield reliable K/Ar ages. The fourth flow from the base of the sequence (Fig. 2), which is a massive biotite–anorthoclase phonolite, yields an age of

2.3.2 40Ar/39Ar age determinations

Considering the error margins, the 40Ar/39Ar analyses of feldspar are in good agreement with the samples analysed for K/Ar from which they were extracted. In contrast, the biotite in sample KY03082101 (from above the Fort Ternan Beds) yields two 40Ar–39Ar age determinations, one of

3 Intercontinental correlations

The East African biochronological scale, which has been calibrated at a number of points by isotopic age determinations, has been used to propose broad correlations to the European mammal zonation (MN Zones) (e.g., [10,24], among others). The fauna from Sansan (France), the niveau repère for MN 6, is often thought to correlate with the fauna from Fort Ternan, although there is a diversity of opinions in the literature about this. Sen [31] correlated the Sansan fauna to polarity zone C5Bn.2n which, in terms of the Baksi [1] GPTS, would make it 16.2–16.3 Ma, which is too old [23]. Daams et al. [4] correlated the Sansan section to C5ABn, which on the same GPTS would make it 14.0–14.3 Ma. Pickford [23] considered that the strata could as well correlate to polarity zone C5Ar.2n, which would make it 13.3–13.4 Ma, using the Baksi [1] version of the GPTS. If, in contrast, calculations are based on other GPTS [3], the correlations proposed would date the Sansan strata to 15.0–15.2 Ma [31], 13.3–13.5 Ma [4] or 12.8 Ma [37]. (Note that in the papers cited, ages are given to two decimal places—in this paper these are rounded out to one place after the decimal.)

The faunal correlations proposed by Pickford and Morales [24] and the combination of isotopic age determinations and palaeomagnetic stratigraphy suggest that the more reliable GPTS, at least for this span of the Miocene period, is that of Baksi [1], although there is sufficient residual uncertainty in the data for other scales to be possible.

4 Discussion

The Fort Ternan fossiliferous deposits have yielded an important Middle Miocene fauna which is the core fauna for Faunal Set IV [16] of the East African Faunal Zonation. Initially considered to be of Pliocene age (in the old sense of the term) [11], it was soon realised that Fort Ternan was significantly older [2]. Initial age determinations based on biotite particles from the site suggested an age of 14 Ma, making it Middle Miocene. This age determination was supported by a subsequent publication [32] despite the fact that a lava flow beneath the sediments yielded an age younger than 14 Ma. It was argued that the isotopic ‘clock’ of this lava flow had been reset by heat emanating from a lahar that overlies the Fort Ternan Beds. A major difficulty with this hypothesis is that the supposed heat from the lahar would have had to bypass the biotite in the Fort Ternan Beds without affecting it in any way and yet alter anorthoclase in the underlying lava, which is appreciably deeper beneath the lahar. Apart from that, anorthoclase is more refractory than biotite and is more difficult to alter in the way postulated.

Subsequently, study of late Middle Miocene faunas from the Ngorora Formation (Members B–D), Kenya suggests ages between 13 and 12 Ma [5] and those from Fort Ternan reveal that they share a number of taxa [15,20] (Table 1). The similarities between the faunas suggest that they were closer in time than indicated by the isotopic age determinations, which, if correct, would mean that there was little evolutionary activity over a period of 1 to 2 Ma. While faunal evolutionary stasis over such extended time periods is theoretically possible, it remains to be demonstrated. Partly because of this, Pickford [23,25] proposed that Fort Ternan is younger than 14 Ma.

Resampling and analysis of the complete succession of lava flows that underlie the Fort Ternan Beds, indicate that indeed the fossiliferous strata are likely to be younger than 14 Ma. Two of the six flows beneath the sediments yield age determinations of

The refinement of the age of the Fort Ternan Beds presented here will impact on allied geological and palaeontological domains including palaeomagnetic stratigraphy and intercontinental faunal correlations.

Acknowledgements

We thank the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (‘Commission des fouilles archéologiques à l’étranger'), the CNRS (PICS 1048, UMR 5143), the ‘Département Histoire de la Terre’ of the ‘Muséum national d'histoire naturelle’, the ‘Collège de France’ (‘Chaire de Paléoanthropologie et de Préhistoire’), and the Community Museums of Kenya. Authorisation to carry out research in Kenya was accorded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. We thank the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research No. 14253006) for financial support and Dr M. Nakatsukasa for funding in the field. The age determinations were carried out in part under the Visiting Researchers Program of the Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier