Version française abrégée

Introduction

Les nombreux travaux menés sur les sols de l'Ouest du bassin de Paris ont montré que ces derniers sont particulièrement sensibles au ruissellement et à l'érosion. Cependant, il apparaît que les études ont été essentiellement menées à l'échelle de la parcelle ou du bassin versant élémentaire et qu'il n'existe pratiquement pas de bilans très précis de l'érosion à l'échelle du bassin versant utilisant des mesures en continu. L'objectif de cette étude est donc : (1) de montrer l'importance de la mesure en continu dans les eaux de surface lorsqu'on veut établir des bilans d'érosion et de transfert précis ; (2) de proposer un bilan d'érosion précis des bassins versants sur sols limoneux de l'Ouest du Bassin de Paris et ainsi d'étudier leur représentativité à l'échelle de la planète.

Contexte et méthodologie

Contexte

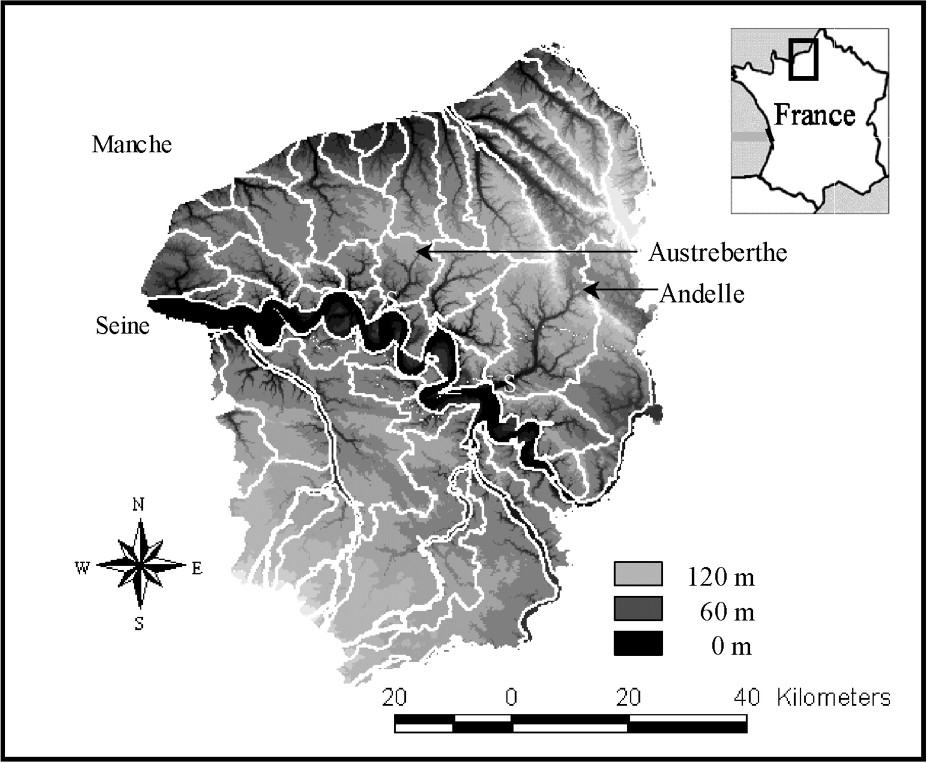

L'Ouest du Bassin de Paris est constitué de vastes plateaux d'altitudes modérées , fortement disséqués par le réseau hydrographique (Fig. 1). Le sous-sol est principalement composé d'un substrat crayeux, recouvert par un manteau de formations superficielles : argiles à silex, dépôts détritiques sablo-argileux tertiaires et lœss, sur lesquels reposent des sols limoneux peu structurés sensibles à l'érosion. Cette sensibilité est renforcée par une occupation du sol dominée par la culture. Le climat est de type tempéré océanique, avec une température moyenne annuelle proche de 13 °C et une pluviométrie annuelle comprise entre 550 et 1100 mm.

Situation of the studied watersheds (Austreberthe, Andelle) in the western Paris Basin: S, measurements station (multiparameter datasounds coupled to automatic water samplers installed at the outlet of the two studied watersheds – Duclair station for Austreberthe and Radepont station for Andelle).

Situation des bassins versants étudiés (Austreberthe, Andelle) dans l'Ouest du bassin de Paris : S, station de mesures (exutoires équipés de sondes multi-paramètres couplées à des préleveurs automatiques d'eau – stations de Duclair pour l'Austreberthe et de Radepont pour l'Andelle).

Notre étude est réalisée sur deux bassins versants situés sur la rive droite de la Seine : Austreberthe (208 km2) et Andelle (710 km2) (Fig. 1).

Méthodologie

Dans un premier temps, nous avons effectué une estimation du flux annuel moyen particulaire à partir d'une synthèse des données ponctuelles existantes (débit et turbidité ou concentration MES) provenant de la direction régionale de l'Environnement et de l'agence de l'eau Seine–Normandie, sur une période de dix ans (1991 à 2000) pour les deux bassins étudiés.

Dans un second temps, les exutoires des deux bassins versants étudiés ont été équipés de sondes multi-paramètres (mesurant en continu la turbidité, la conductivité électrique, la température et la hauteur de l'eau), couplées à des préleveurs automatiques d'eau (Fig. 1).

Les chroniques de mesures en continu permettent d'établir un flux particulaire et un bilan d'érosion précis, qui peuvent alors être comparés aux bilans calculés : (1) à partir des mesures ponctuelles sur les mêmes bassins versants et ainsi quantifier l'erreur de ce dernier, (2) sur d'autres bassins versants à l'échelle de la planète, afin d'étudier la représentativité de l'érosion de l'Ouest du bassin de Paris.

Comparaison des bilans de transfert particulaire calculés à partir des données ponctuelles et de la mesure en continu dans les eaux de surface

À partir des mesures ponctuelles mensuelles réalisées à l'exutoire de l'Austreberthe de 1971 à 1991 (qui ne prennent pas en compte les plus forts débits ; Fig. 3), on obtient un flux moyen annuel de 1467 t an−1 de matières en suspension. À partir des mesures effectuées en continu dans le cadre de ce travail, le flux annuel de MES est de 3328 t an−1, soit une différence de 44% entre les deux bilans.

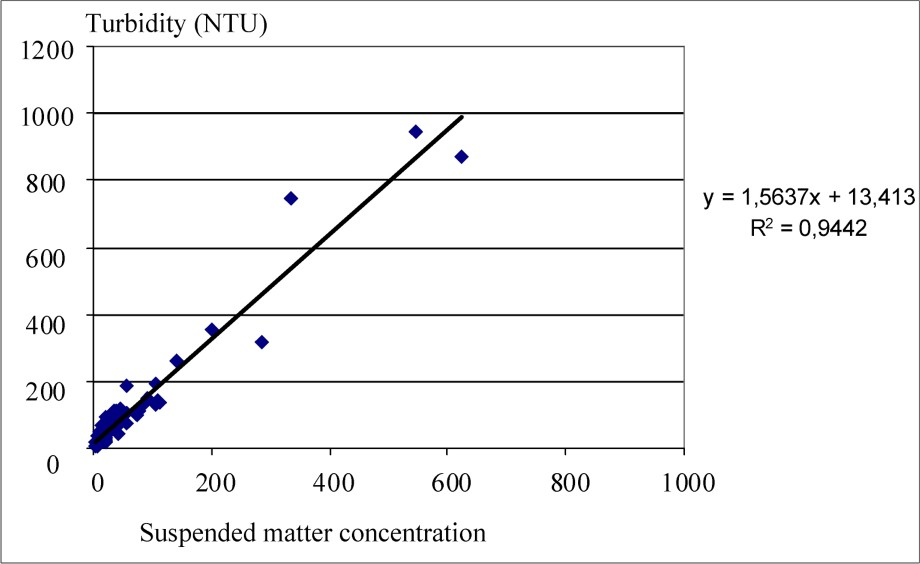

Mathematical relationship between turbidity and suspended matter concentration (example of the Austreberthe watershed).

Relation mathématique entre turbidité et concentration en MES (exemple du bassin versant de l'Austreberthe).

Bilan d'érosion des bassins versants sur sols limoneux de l'Ouest du bassin de Paris et représentativité à l'échelle de la planète

Les taux d'érosion obtenus sont de 16 t km−2 an−1 pour l'Austreberthe et de 21 t km−2 an pour l'Andelle.

Une synthèse bibliographique des taux d'érosion à différentes échelles d'espace, depuis les grands fleuves mondiaux jusqu'aux petits bassins versants (avec une surface inférieure ou égale à 1000 km2 comme celle de l'Austreberthe et de l'Andelle), a été effectuée. Les taux d'érosion varient de :

- – 4 à 2514 t km−2 an−1 pour les 60 plus grands fleuves du monde [23–25] ;

- – 3,5 à 1825 t km−2 an−1 pour des bassins versants de diverses tailles (64 à 3,2 millions de km2) dans différents contextes climatiques et reliefs de la planète [28] ;

- – 21 à 18 000 t km−2 an−1 pour des bassins à différentes échelles emboîtées dans la cordillère des Andes de Bolivie [8,9] ;

- – 7,5 à 1880 t km−2 an−1 pour de petits bassins versants (de taille inférieure à 1000 km2).

Compte tenu de ces résultats, nous en déduisons que les bassins versants sur sols limoneux de l'Ouest du bassin de Paris présentent des taux d'érosion annuels parmi les plus faibles à l'échelle de la planète. Ceci est vraisemblablement lié au climat tempéré et au relief peu contrasté de cette région.

À première vue, ces résultats amènent à penser qu'il n'existe pas de problème grave d'érosion dans cette région. Cependant, il n'en est rien. En effet, ces bilans annuels ne reflètent pas les modes de fonctionnement différents de ces bassins (Tableau 2), avec notamment un fonctionnement qui tend vers un type « torrentiel » dans le cas de l'Austreberthe.

Hydrological behaviours of the two studied watersheds (Austreberthe and Andelle)

Comportements hydrologiques des deux bassins versants étudiés (Austreberthe et Andelle)

| Austreberthe | Andelle | |

| Watershed area | 208 km2 | 710 km2 |

| Rainfall quantity | 68 millions m3 (1009 mm) | 249 millions m3 (949 mm) |

| Restitution rate | 328 mm – 32.5% | 335 mm – 35.3% |

| Response rainfall/flow | 3 h 30 to 5 h | 10 h to 25 h |

| Turbidity number of flood > 100 NTU | 14 | 7 |

| Turbidity max | 1540 NTU | 256 NTU |

| During to obtain the half of annual | 33 days | 52 days |

| flow of suspended matter |

Conclusion

Il apparaît donc indispensable d'opérer un suivi en continu du débit et de la charge en suspension dans les eaux de surface, incluant ainsi la totalité des épisodes de crues dont l'importance est essentielle dans le transport solide, afin d'améliorer les bilans d'érosion et de définir le fonctionnement des bassins versants.

Il a ainsi été démontré que l'erreur effectuée sur le bilan obtenu à partir de données ponctuelles mensuelles sur 10 ans peut atteindre 44%. Les chroniques de mesures en continu ont permis de calculer un taux d'érosion précis de 16 à 21 t km−2 an−1 pour les bassins versants sur sols limoneux de l'Ouest du bassin. Ces taux d'érosion sont parmi les plus faibles à l'échelle de la planète. Cependant, le bilan annuel ne reflète pas le fonctionnement différent de ces bassins, qui peut tendre vers un type torrentiel (exemple de l'Austreberthe).

L'étude d'hydrosystème ne peut donc se restreindre à des moyennes et des bilans effectués à partir de mesures ponctuelles, mais nécessite un suivi en continu de différents paramètres, qui permet d'enregistrer la succession d'épiphénomènes à l'échelle temporelle ayant une importance capitale dans les flux d'eau et de sédiment depuis les continents jusqu'aux océans, et donc sur le cycle hydrologique global.

1 Introduction

Soils of the plateau in the western Paris Basin mainly consist of leached brown soils on loess formations [6,7], also called ‘neoluvisols or luvic brunisols’.

These soils were the subject of many studies during the last years, the main objective of which being the understanding and quantification of erosion processes [1,2,17–21,26,29], etc. These works showed that these little structured loamy soils are particularly sensitive to runoff and erosion in the western Paris Basin and more generally in northwestern Europe, and that the consequences of these phenomena may be much important (gullying, soils destruction, torrential flow, turbidity of drinking water, floods, collapses, modifications of aquatic biotopes, etc.).

In spite of this abundant bibliography, it appears that the studies were mainly led at the scale of the parcel (a few square metres to a few hectares) or elementary watershed (a few km2), and that practically there is no very accurate erosion balance at the scale of the watershed using high-frequency measurements.

The interest and aim of this study are:

- – (1) to show the importance of continuous measurements in surface water to establish precise erosion rates and sediment yields;

- – (2) to propose accurate erosion rates and sediment yields for watersheds on loamy soils in the western Paris Basin and thus to study their representativeness at the global scale.

2 Context and methodology

2.1 Context

The western Paris Basin consists of vast plateaus strongly dissected by the hydrographic network. The relief is characterized by moderate altitudes and a plateau morphology that depend on the sedimentary basement and its recent evolution [32]. The geomorphology of this region is contrasted on both sides of the River Seine [12] (Fig. 1). In the North of the river, the plateau of the ‘Pays de Caux’ is strongly dissected by drained valleys and many dry small valleys. It is bordered to the northwest by littoral cliffs and the English Channel. We notice the existence of eight rivers, tributaries of the River Seine (from the west to the east: Lézarde, Commerce, Sainte-Gertrude, Rançon, Austreberthe, Cailly, Robec, Andelle) and ten littoral rivers (from the west to the east: Valmont, Durdent, Le Dun, Sâane, Scie, Varenne, Béthune, Eaulne, Yères, Bresle). South from the River Seine, the plateaus are more monotonous and are little dissected, with only two main rivers (Risle and Eure), with their tributaries.

The plateau of the western Paris Basin consists of a sedimentary substratum that presents a main dip towards the east. This substratum is mainly composed of Upper Cretaceous chalks, except for the Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous terranes which outcrop thanks to local convexities (example: anticline of the ‘Pays de Bray’). These chalks (more or less rich in flints) are dated from the Cenomanian to the Campanian [5]. The chalk substratum is covered by superficial deposits made up of alterites with flints (also named clay-with-flints) [11,13–15,31], Tertiary sandy-clay residual deposits (in pocket to the top of the clay-with-flints) [12] and loess [16].

There exists a relationship between the morphology and the soil use in this region. The typical soil use can be divided into three main types: (1) the plateaus mainly cultivated, (2) the slopes covered with woods, (3) the bottom of the valleys which are farmed and/or in grassland, especially in the low flow channel. In this region, the farmed zones represent 50 to 60% of the surface of the watersheds [10].

The climate is of moderate oceanic type, with an annual average temperature of about 13 °C. The averages calculated over 30 years indicate an annual pluviometry ranging from 550 to 1100 mm, with an interannual variability of approximately 25%. We notice a difference between the area located to the north of the River Seine (800 to 1100 mm) (which is situated the studied watersheds) and the area to its south (550 to 800 mm).

Our study is carried out on two watersheds located on the right bank of the Seine: Austreberthe (208 km2) and Andelle (710 km2) (Fig. 1). The geomorphological context of these two watersheds is identical to that described for the western Paris Basin, except that the upstream part of the Andelle (representing 5% of the watershed) is located in the ‘Pays de Bray’. In this part of the watershed, ancient geological formations outcrop: Wealdian sands, grey clays, mixed clays and green sands of the Aptian and the Albian. The nature of these formations is not favourable to farming and the soil is used as grassland in this area.

2.2 Methodology

An estimation of the average annual solid discharge was firstly carried out using a synthesis of existing sporadic data (flow and concentration of suspended sediment) of the DIREN (Regional Direction of the Environment) and the Seine–Normandy Water Agency over ten years (1991 to 2000) on the two studied watersheds.

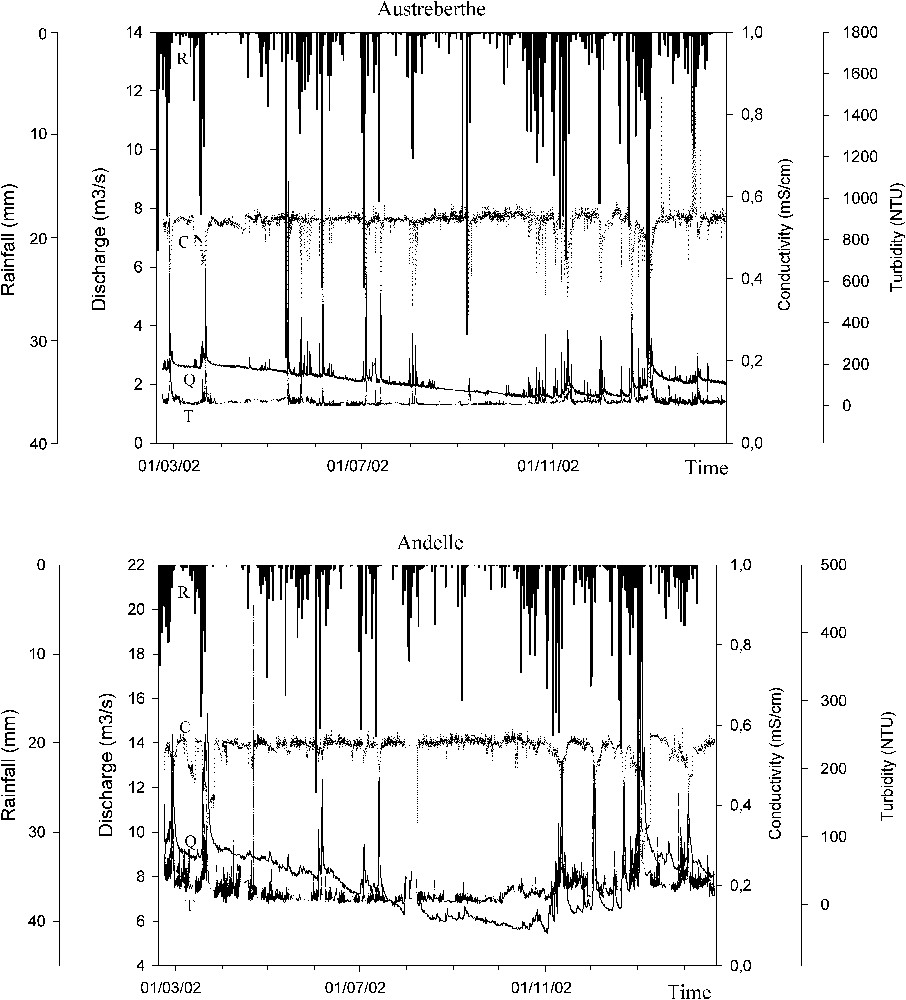

In a second time, we analysed data collected from multiparameter datasounds (6820 YSI) coupled to automatic water samplers (ISCO 6700) that were installed at the outlet of the two studied watersheds (Fig. 1: Duclair station for Austreberthe, and Radepont station for Andelle). The various parameters recorded by the datasounds were turbidity, conductivity, temperature and water level (Fig. 2), and the sampling interval was 30 min. The automatic water samplers allowed the sampling and the recording of the measurements taken by the sounds. This device is particularly adapted to continuous monitoring of solid discharge in water in hydrogeology [27] and surface hydrology [3,35].

Continuous measurements records of rainfall, flow, turbidity and conductivity during one year at the outlet of the Austreberthe and Andelle Rivers: R, rainfall; Q, flow (or water discharge); T, turbidity; C, conductivity.

Chroniques de mesures en continu de débit et turbidité, enregistrées pendant une année sur les rivières de l'Austreberthe et de l'Andelle : R, précipitation ; Q, débit ; T, turbidité ; C, conductivité.

The water samples were analysed in the laboratory. The sampling interval was 16 h during steady periods, and 1 h during floods. The turbidity of each sample was measured in order to check the measurements of the sounds. Suspended sediment concentration was measured in water samples for the calibration of turbidity high-frequency measurements.

Turbidity and suspended sediment concentration are linked by a linear relationship (Fig. 3) and make it possible to determine a theoretical suspended sediment concentration. Sediment fluxes (kg s−1) are subsequently computed by multiplying the concentration (kg m−3) at time interval i by discharge (m3 s−1) at the same time interval i () [30].

The computed solid discharge and erosion balance could be compared with those calculated: (1) from sporadic measurements on the same watersheds and thus to quantify the subsequent error, (2) on other watersheds at the global scale in order to study the representativeness of erosion in the western Paris Basin.

3 Comparison of the calculated particle transfer balances from the sporadic data and high-frequency measurements in surface streams

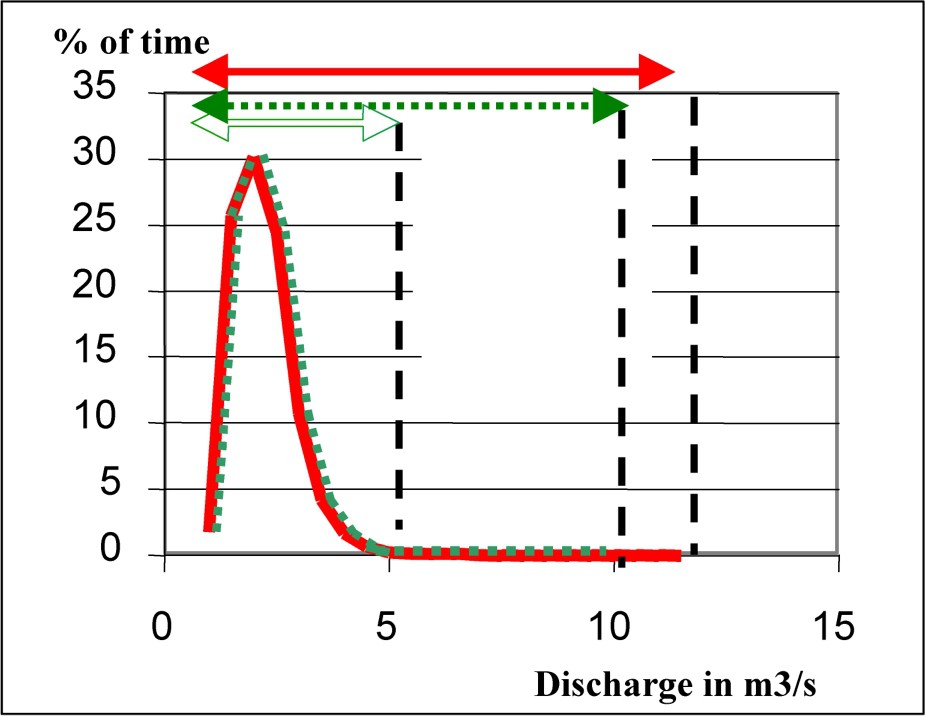

The synthesis of sporadic data makes it possible to highlight several problems: (1) the location of the measuring sites is not always sufficiently downstream (i.e., sometimes far from the outlet) to integrate the whole watershed, (2) the time interval of suspended sediment concentration data is too large (monthly or semi-annual), which as a result prevents from spanning the entire range of discharge – i.e., no data during strong floods (Fig. 4).

Problem of representativeness of the existing sporadic data of concentration in suspended matter (data of the Regional Direction of the Environment and Agency of the Water in the Seine Normandy): absence of measurement during the strong flows. ------ Flow between 1991 and 2000; - - - - - - flow when the solid discharge is measured.

Problème de représentativité des données ponctuelles existantes de concentration en MES (données DIREN et Agence de l'Eau Seine Normandie) : Absence de mesure pendant les forts débits. ------ Débit entre 1991 et 2000 ; - - - - - - débit lorsque le flux solide est mesuré.

This remark is very important for the calculation of the transfer and mechanical erosion balances. Indeed, in the case of Austreberthe, the suspended sediment concentration was measured at its outlet (Duclair), from 1971 to 1991, for discharge ranging from 0.9 to 4.74 m3 s−1, whereas discharge usually varies between 1.07 and 11.5 m3 s−1 in this period. From these monthly measurements, we obtained an annual mean discharge of suspended sediment of 1467 t yr−1.

The annual discharge of suspended sediment obtained from high-frequency measurements is 3328 t yr−1. The difference is of 44% between the two balances. This is related to one particularly rainy February with significant floods: computing the monthly flux for February 2002 gives a value of 1080 tons, which covers almost the totality of the annual balance obtained with sporadic data.

In the case of Andelle, it was not possible to carry out the same comparison because of insufficient suspended sediment concentration data (semi-annual data only). Moreover, the measuring site of the DIREN is not located downstream enough to integrate the global watershed: the more downstream DIREN station is located in the central part of the watershed.

4 Erosion balance of the watersheds on loamy soils of the western Paris Basin and representativeness at the earth scale

Data obtained from high-frequency measurements for both Austreberthe and Andelle were used to calculate a precise mechanical erosion rate. This calculation was carried out from the suspended sediment concentrations only; the bed load was not measured and thus not included. In any case, it is generally admitted that bed load represents at the maximum 10% of total exported mass in our geomorphological and climatic context [28]. Moreover, as for all the studies led at scale of the watershed, the erosion rate is a global parameter that does not account for settlement (storage sections of erosion products) and remobilisation of particles.

The calculated erosion rates are 16 t km−2 yr−1 for the Austreberthe watershed and 21 t km−2 yr−1 for the Andelle watershed.

The comparison between our values and those of the literature is difficult inasmuch as particle discharge and erosion balance are usually investigated:

- – at different spatial scales, from the parcel (a few square metres to a few hectares) by agronomists to the largest rivers of the world by geomorphologists and geologists;

- – using different sampling intervals: measurements of turbidity and/or concentration of suspended sediment according to a monthly or semi-annual time step generally, more rarely daily time steps.

However, a bibliographical synthesis of erosion rate for different types of watersheds (different spatial scales) was performed: from large world rivers to small watersheds (area like Austreberthe and Andelle). This synthesis is not exhaustive. Nevertheless, it makes it possible to assess the representativeness at the global scale of the erosion of the watersheds on loamy soils in the western Paris Basin.

From a synthesis on the 60 larger rivers of the world, Ludwig et al. [25], Ludwig and Probst [23,24] indicate erosion rates ranging from 4 to 2514 t km−2 yr−1. According to these authors, this great variability can be correlated to the hydroclimatic, geomorphological and lithological contexts of the watersheds.

The study carried out by Meybeck et al. [28] on the daily variability of the suspended sediment concentration and discharge in the rivers is particularly interesting, since it is the first synthesis at the global scale based on daily measurements of suspended sediment concentration, spanning the various climatic contexts and planet reliefs for various sizes of watershed (from 64 to 3.2 million km2). The calculated erosion rates vary from 10 to 5000 t km−2 yr−1, that is 3.5 to 1825 t km−2 yr−1. Meybeck et al. [28] indicate that this variability is related to several factors, including not only inter-watershed features (relief, lithology, climate, vegetation and surface of the watershed), but also intra-watershed features (retention of suspended sediment in lakes, ponds and floods plains, groundwaters).

Works achieved by Guyot [8] and Guyot and Hérail [9] on about 50 watersheds in the Andes Cordillera of Bolivia is also interesting, because these studies integrate watersheds according to various encased scales, from 17 to 81 300 km2, in different climatic contexts from one slope to another of the Cordillera, with various lithologies. The obtained erosion rates are strongly variable, from 21 to 18 000 t km−2 yr−1. In the Andes Cordillera, erosion is directly controlled by the amount of precipitation and lithology: the strongest erosion rates are located in those watersheds submitted to the strongest precipitation amounts and that present syntectonic Cenozoic sedimentary infillings.

Another bibliographical synthesis of the erosion rates for small watersheds (area ), such as those of Austreberthe or Andelle, was also carried out (Table 1), showing again a great variability (from 7.5 to 1880 t km−2 yr−1), depending on various factors stated previously in the study of Meybeck et al. [28].

Comparative table of the mechanical erosion rates of few examples of small watersheds (surface ) in various localities of the Earth

Tableau comparatif des taux d'érosion pour quelques exemples de petits bassins versants (surface ) situés dans différentes localités du Globe

| Studies | Location | Watershed area (km2) | Erosion rate (t km−2 yr−1) |

| Binda et al. (1986), | Annapolis, Canada | 546 | 7.5 |

| Water Survey of Canada (1995) (in [28]) | |||

| Guyot (1993) (in [28]) | Bermejo, Bolivia | 480 | 814 |

| Guyot (1993) (in [28]) | Elvira, Bolivia | 64 | 416 |

| Guyot (1993) (in [28]) | Espejos, Bolivia | 203 | 1880 |

| DEDP (1996, 1997) (in [28]) | Huai Mae Ya, Thailand | 84.8 | 99.5 |

| DEDP (1996, 1997) (in [28]) | Khlong Mala, Thailand | 188 | 186 |

| DEDP (1996, 1997) (in [28]) | Khlong Sok, Thailand | 892 | 120 |

| DEDP (1996, 1997) (in [28]) | Nam Mae Pai, Thailand | 369 | 83.5 |

| [36] | Southeastern Spain | 130 | 120 |

| Meybeck et al. (1999) (in [28]) | Mélarchez, tributary of the ‘Grand Morin’ | 7 | 14.5 |

| [33] | Agly, eastern Pyrenees | 1045 | 103 |

| [34] | Têt à Vinça, eastern Pyrenees | 940 | 638 |

| [4] | Druance, ‘Basse-Normandie’ | 90 | 50 |

| [27] | Bébec, western Paris Basin | 8 | 21 |

| Notre étude | Austreberthe, western Paris Basin | 208 | 16 |

| Notre étude | Andelle, western Paris Basin | 710 | 21 |

It appears that the Austreberthe and Andelle watersheds erosion rates are among the smallest on the Earth, whatever the scale concerned (large world rivers, small watersheds, encased scales watersheds like those of the Andes Cordillera of Bolivia). In addition, our values are similar to that of Massei [27] (21 t km−2 yr−1) obtained for a smaller () elementary watershed in the same context, in the western Paris Basin. We deduce that the erosion rates of the watersheds on loamy soils in the western Paris Basin appear to be among the smallest at the global scale, which may be related to the temperate climate and the low contrasted relief of this area.

Nevertheless, it does not indicate that erosion phenomena are not a great concern in this area, because this annual balance does not reflect the behaviour of these watersheds (Table 2, Fig. 3). The two studied watersheds effectively present very different behaviours. The Austreberthe watershed has a stronger reactivity to rainfall than the Andelle. Turbid floods with turbidity exceeding 60 NTU are more frequent for the Austreberthe than the Andelle. Moreover, sediment discharge during strong floods is much more important for the Austreberthe than for the Andelle. It results that half of the annual flux of suspended sediment is reached in 33 days for the Austreberthe watershed, while it is reached in 88 days for the Andelle watershed. These results underline the major interest and necessity of continuous monitoring of suspended sediment fluxes to ensure that short but intense flood events are effectively taken into account.

According to the ‘Plan of Prevention of Risks’ (PPR) of floods by overflow and runoff established by Hauchard [10], the behaviour of the Austreberthe watershed tends towards a torrential type hydrosystem, while that of the Andelle can be described as of a ‘generalized’ type. In the ‘generalized-behaviour’ hydrosystem, the entirety of the watershed operates. In the ‘torrential-behaviour’ hydrosystem, the watershed produces torrential turbid flows, limited in time, in response to strong or very strong rain events (great reactivity to precipitations). In brief, these two watersheds, although they reveal drastically different behaviours, present relatively similar erosion rates: as a matter of fact, the important and strong erosion limited in time observed for the Austreberthe watershed is compensated, in terms of annual balance, by a lower but more continuous erosion in the Andelle watershed.

The different hydrological behaviours of the Andelle and Austreberthe watersheds are linked to multiple factors that influence transfer processes, which are consequently difficult to understand. Nevertheless, according to current studies in this area, morphological characteristics would be the most significant factor explaining these different hydrological behaviours, land use and rainfall patterns being almost the same for each watershed. Among the various morphological parameters, the watershed area and the slope of the main drain could explain these different behaviours. It is recognized in the literature that the temporal variability of the concentration and discharge of suspended sediment decrease with the increase of the watershed area [28]... The difference of area of the two watersheds, 710 km2 for Andelle and 208 km2 for Austreberthe, could be at the origin of these different hydrological behaviours. The slope of the main drain, higher for Austreberthe (4.7‰) than for Andelle (2.9‰), would explain faster responses to rainfall, consequently playing a major role in the hydrological functioning of each watershed. However, several other morphological parameters such as the draining frequency, fractal dimension of the hydrographic network, etc., might play quite a significant role in the hydrological regime, and their roles are currently being studied.

5 Conclusion

It appears essential to perform continuous monitoring (i.e., high-frequency measurements) of discharge and suspended sediment load, including the all floods, in order to improve the estimations of solid transfer and erosion balances. This work joined one of the conclusions of the recent study of Li et al. [22] concerning the calculation of erosion rate on the Kaoping watershed in Taiwan: large series of datasets are required for the calculation of erosion balance to reduce uncertainties and smooth time variability.

We showed that the error produced on the erosion balance obtained from monthly sporadic data over 10 years could reach 44%.

The continuous measurement records made it possible to calculate a precise erosion annual rate from 16 to 21 t km−2 yr−1 for the watersheds on loamy soils in the western Paris Basin. The comparison between these values and the erosion rates of the watersheds at various spatial scales (from large world rivers to small watersheds) showed that the erosion rates of watersheds in the western Paris Basin are among the weakest at the global scale.

However, the annual balance does not reflect the behaviour of these watersheds. Indeed, these watersheds, with the same annual erosion rate, present different hydrological behaviours, which can tend towards a ‘torrential’ type (this means that they can be dominated by large events) like the Austreberthe watershed. These differential types of behaviours could be assessed only by continuous measurement of the flow and solid discharge.

The study of hydrosystems cannot be restricted to averaging and balances carried out from sporadic measurements, but requires a continuous monitoring of various parameters (hydrological and physicochemical parameters) that allow us to record the succession of time-localized epiphenomena having an essential importance in the water and sediment flows from the continental zones to the oceans, in the transfer and storage of the nutriments and pollutants, on the biodiversity and the evolution of the continental and aquatic ecosystems..., and thus in the global water cycle.