1 Introduction

In France, the Massif Central is the largest area where Variscan metamorphic and plutonic rocks are exposed and can be studied. The entire massif belongs to the northern Gondwanian margin, which corresponds to the southern continent involved in the Variscan collision. Due to the limited amount of post-Permian reworking, the French Massif Central (FMC) is a suitable place to understand the structure and evolution of the lower plate of the Gondwanian Domain. This article aims to provide an overview of the structure and tectono-metamorphic evolution of the FMC and to discuss the still controversial points related to its geodynamic evolution.

2 The bulk architecture of the Massif

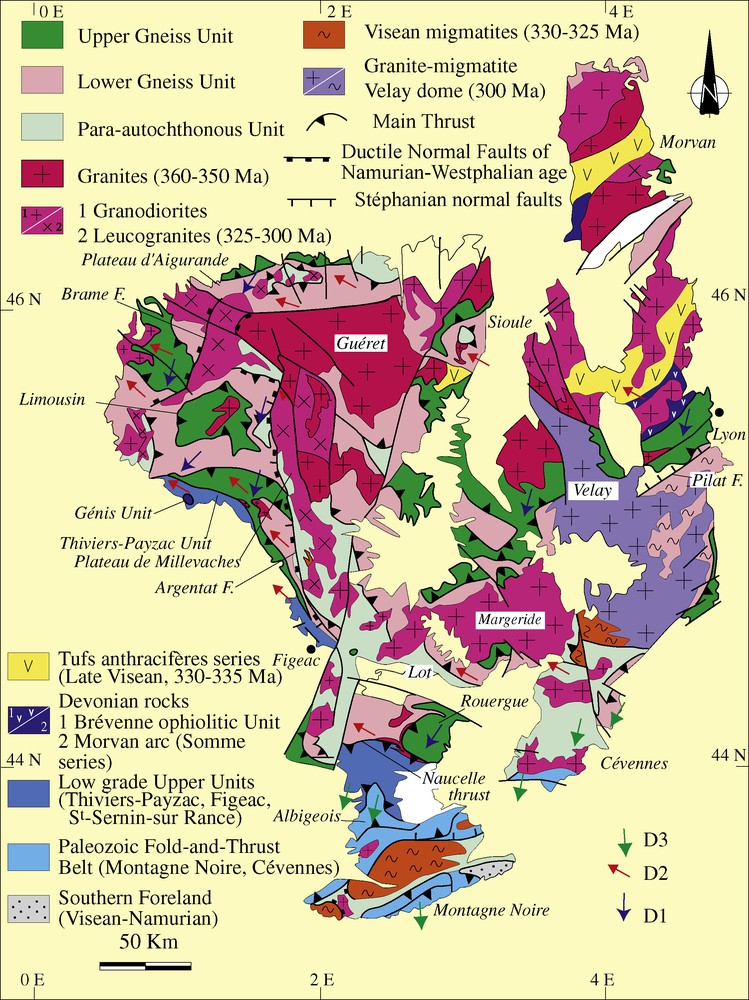

The Massif Central, like the southern part of the Massif Armoricain or the southern Vosges, is a stack of metamorphic nappes ([29,39] and associated references). From bottom to top, and from south to north, the following units are recognized (Figs. 1 and 2).

Structural map of the French Massif Central according to [29] and [28].

Fig. 1. Schéma structural simplifié du Massif central français, d’après [29] et [28].

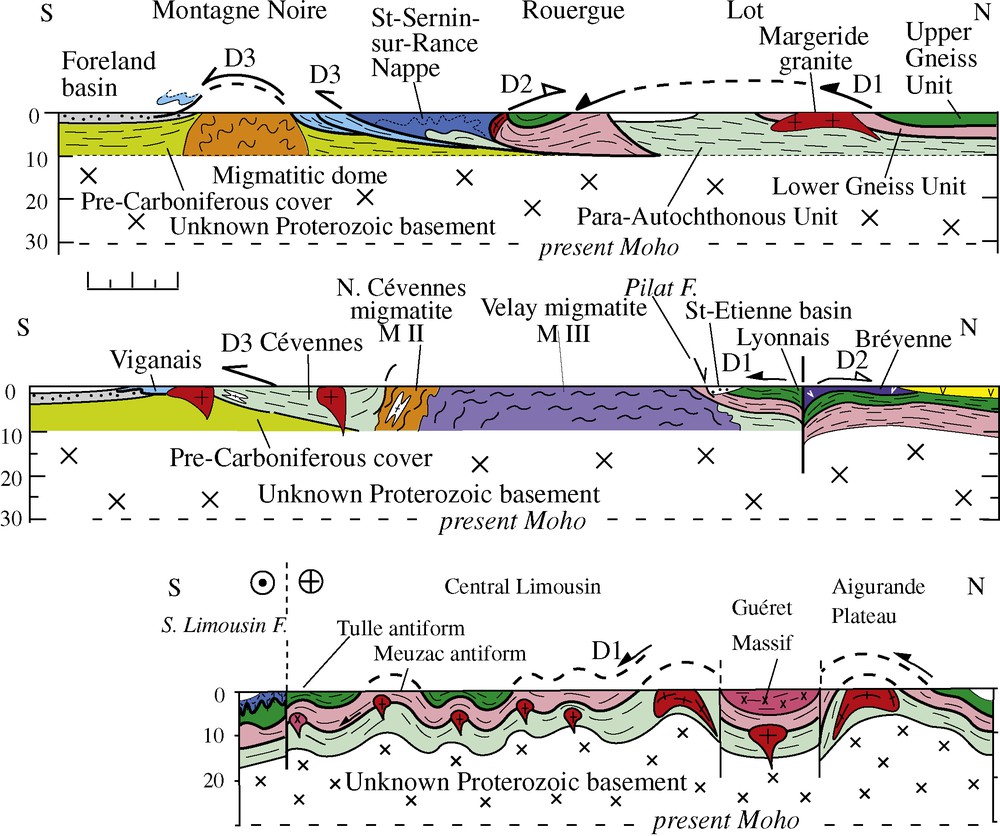

Simplified cross-sections throughout the French Massif Central showing the stack of nappes and polyphase deformation. The post-Carboniferous deposits have been omitted.

Fig. 2. Coupes simplifiées du Massif central montrant les déformations polyphasées et l’édifice de nappes. Les dépôts post-Carbonifère supérieur n’ont pas été représentés.

2.1 Foreland Basin

The foreland basin developed along the southernmost part of the Massif Central. It is a Middle Carboniferous (Visean-Namurian) turbiditic basin that extends southward below the coastal plain of the Mediterranean Sea and up to the Pyrénées. In the Montagne Noire, proximal turbiditic facies includes kilometer-scale olistoliths of Paleozoic sedimentary rocks derived from the adjacent unit [23].

2.2 Paleozoic Fold-and-Thrust Belt

The Paleozoic Fold-and-Thrust Belt consists of Early Cambrian to Middle Carboniferous weakly- or un-metamorphosed sedimentary rocks displaced to the south as thrust sheets or as kilometric-scale recumbent folds, which are well developed in the Montagne Noire. The Cambrian-Ordovician passive margin deposits are unconformably overlain by Early Devonian terrigeneous rocks, followed by a Middle Devonian to Early Carboniferous kilometer thick carbonate platform. The almost complete absence of Silurian rocks and the Early Devonian unconformity argue for an Early Paleozoic tectonic event (at ca 410–400 Ma), which is also recorded to the north in the metamorphic rocks.

2.3 Par-autochthonous Unit

To the north, the Par-autochthonous Unit is thrust over the Paleozoic sedimentary series. It is formed by greenschist to epidote-amphibolite facies metapelites, quartzites and minor limestones and amphibolites. This Par-autochthonous Unit is widely exposed in the southern FMC (Cévennes and Albigeois). In the northern FMC, the Par-autochthonous Unit crops out in tectonic windows surrounded by the higher-grade rocks of the structurally higher units. Due to metamorphic recrystallizations, fossils are not preserved, and the protolith ages are unknown; some Ordovician plutons (now transformed into orthogneiss) intrude the series and Ordovician detrital zircons are found in some volcaniclastic layers.

2.4 Lower Gneiss Unit (LGU)

The LGU is composed of metagreywackes, metapelites and metarhyolites intruded by numerous Cambrian to Early Ordovician porphyritic alkaline granitoids, which have been transformed into augen orthogneiss during the tectonic-metamorphic events. The LGU underwent Middle Devonian metamorphism leading to crustal melting coeval with a ductile shearing dated, in the Limousin, at 375–370 Ma and attributed to the D1 event (cf. below: [21,29,37]). Moreover, the LGU also experienced a medium-pressure/medium-temperature metamorphism with a biotite-garnet-staurolite assemblage, and attributed to the D2 event.

2.5 Upper Gneiss Unit (UGU)

The UGU forms the overlying nappe. The protoliths of this unit are partly similar to those of the LGU: however, the UGU is also characterized by a bi-modal magmatic association of acidic lavas, tuffs and mafic rocks (basalts, gabbros, rare ultramafic rocks) called the “leptynite-amphibolite complex”. The UGU contains high-pressure (HP) rocks, such as eclogites or HP granulitic orthogneiss, that locally may reach the coesite-eclogite facies [34,38,60]. Blueschists, however, are very rare in the FMC. The upper part of the UGU consists of Devonian migmatites, with ages around 385–380 Ma [21,29,37], formed by the partial melting of pelitic and quartzo-feldspathic rocks. These rocks contain amphibolite blocks derived from retrogressed eclogites that did not experience partial melting. In the Limousin, some metagabbros and serpentinized ultramafics are considered by some authors to represent ophiolites [18]. However, it is worth noting that siliceous sediments, i.e. radiolarian cherts or siliceous shales are absent. On the basis of recent work in the Mts du Lyonnais, the UGU might be subdivided into several subunits, such as:

- • the bimodal quartzo-feldspathic (leptynite-amphibolite) series;

- • a block-in-matrix series with eclogites and peridotites enclosed in a paragneiss matrix;

- • a mafic unit devoid of HP rocks.

At the present state of knowledge, it is not possible to provide a general map of these subunits for the entire MCF; therefore, the structural map (Fig. 1) does not take this subdivision into account.

The units described above represent the classical nappe pile of the FMC in which the metamorphism increases from bottom to top. This architecture is often described as a “Himalayan-type inverted metamorphism”; however, other units also have to be considered.

2.6 Thiviers-Payzac Unit

The Thiviers-Payzac Unit is the highest tectonic unit of the allochthonous stack in the Massif Central, developed in the South Limousin area [34], and extending southward to the Rouergue where it is called the St-Sernin-sur-Rance Nappe [33] (Fig. 1). It is composed of Cambrian metagreywackes, rhyolites and quartzites metamorphosed under amphibolite facies conditions, and has never experienced HP metamorphism. The Thiviers-Payzac Unit is lithologically similar to the Par-autochthonous Unit. On the basis of metamorphic and structural observations [29,31,59] and supported by inferences based on interpretation of seismic data [4], the Thiviers-Payzac Unit is interpreted to be allochthonous on the UGU. Emplacement of the Thiviers-Payzac Unit is a result of the second deformation event (D2, cf. below).

2.7 Brévenne Unit

The Brévenne Unit consists of pillow basalts, diabase dykes, gabbros, ultramafics, siliceous sedimentary rocks and massive sulfide deposits of Devonian age, interpreted as an ophiolitic nappe [53,55,61] metamorphosed to greenschist facies conditions. The geochemistry of the mafic rocks is in agreement with a back-arc basin setting for the Brévenne ophiolite [55,61]. This unit is separated from the UGU, to the south, by a Middle Carboniferous dextral wrench fault [15,38], although some authors suggest an earlier displacement to the NW over pre-Late Devonian gneiss [26,42]. The age of this early ductile shearing is constrained by an Early Visean unconformity [35].

2.8 Génis Unit

In the South Limousin, some small outcrops of gabbro, mafic metavolcanic rocks (pillow lavas in places), radiolarian cherts, siliceous red shales and Middle Devonian limestones form the Génis Unit. The structural and paleogeographic setting of the Génis Unit is not yet settled. Although sometimes considered as an ophiolitic nappe [39], the lack of continuous outcrop also suggests an interpretation that the Génis Unit might be a Late Devonian-Early Carboniferous olistostrome, reworking oceanic rocks similar to those of the Brévenne Unit.

2.9 Somme Unit

The Somme Unit is developed only in the northeastern part of the FMC. It is composed of undeformed and unmetamorphosed volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks and massive sulfide deposits of Middle to Late Devonian age. The magmatic rocks have calc-alkaline geochemical affinities typical of a magmatic arc setting [16].

2.10 “Tuffs anthracifères” series

The “Tuffs anthracifères” series is developed only in the northern FMC, from the North Limousin to Morvan and include terrigeneous rocks (sandstone, shales, conglomerates and coal measures) and felsic magmatic rocks (dacites and rhyolites), which are dated as Late Visean (ca 330 Ma, [7]). These unmetamorphosed rocks unconformably overlie Late Devonian-Early Carboniferous plutonic or metamorphic rocks. The “Tuffs anthracifères” series is coeval with the Fold-and-Thrust Belt. Thus it supports the north-south propagation of the tectonic events throughout the entire FMC.

3 The succession of the tectonic and metamorphic events

The stack of nappes described above results from six main tectonic and metamorphic stages.

3.1 The D0 event

This earliest event is coeval with the HP to ultra high-pressure (UHP) metamorphism recorded in the eclogite facies rocks of the UGU. Although most of the HP rocks have mafic protoliths, HP orthogneisses are locally found. The UGU eclogites record pressure and temperature conditions of 1.8–2 GPa and 650–750 °C, respectively [38], and available radiometric ages cluster around 415 Ma [52]. A mylonitic foliation and mineral lineation, coeval with the HP event is, in places, developed in eclogites and peridotites: however, the regional distribution of these structures is not available at present.

3.2 The Early to Middle Devonian D1 event

This tectonic-metamorphic event is coeval with the crustal melting of the pelites and granitoids of the UGU and LGU, with mafic rocks remaining as amphibolite blocks in migmatites. The migmatisation is dated as Middle Devonian (385–375 Ma) in the Limousin or Lyonnais [21,29, 37 and references therein]. Pressure–temperature (P–T) estimates from garnet-plagioclase and garnet-biotite pairs provide metamorphic conditions of 0.7 ± 0.05 GPa and 700 ± 50 °C respectively [49,57].

The flat-lying migmatitic foliation exhibits a NE–SW trending (N30 to N60E) stretching lineation marked by fibrolitic sillimanite or biotite in migmatites and biotite or amphibole in mafic rocks. Shear criteria indicate a top-to-the-southwest displacement [26,31,39,57]. Amphibolites in the northern MCF (Plateau d’Aigurande and the Couy borehole) have yielded biotite and hornblende 40Ar/39Ar ages ranging from 390 to 381 Ma [6,14]. In Morvan, the occurrence of Middle Devonian unmetamorphosed and undeformed rocks of the Somme Unit and eclogite relics in migmatite [32] suggests that, at least in the northern part of the Massif Central, the HP rocks were already exhumed before the Middle Devonian [26].

3.3 The Late Devonian-Early Carboniferous D2 event

In the LGU, UGU, Thiviers-Payzac, and Brévenne Units, the major structure related to this stage is a NW–SE trending stretching lineation developed either on flat-lying or steeply dipping foliations (Fig. 1).

Thermo-barometric constraints are well-established in the Limousin and Rouergue [2,19,31]. In the UGU, syn-D2 minerals, crystallized along the NW–SE lineation, indicate 0.7–1 GPa and 600–700 °C metamorphic conditions. Paragneiss belonging to the LGU have yielded nearly similar conditions of 0.8–1 Gpa and 550–600 °C. In the LGU, amphibolites which have never experienced the HP event indicate 0.8–1 GPa and 700–800 °C [60], and Thiviers-Payzac Unit registers P–T conditions of 0.4–0.6 GPa and 400–500 °C [20]. Top-to-the-NW ductile shearing is dominant from the SE Massif Central up to the southern part of the Massif Armoricain [2,5,8,19,28]. In the Rouergue, a kilometer-scale, flat-lying synmetamorphic ductile shear zone, called the “Naucelle thrust” transports the Para-autochthonous Unit to the north-west above the LGU. This northwestward shearing reworks D1 isoclinal folds and stretching lineations developed in the LGU and UGU [19].

Top-to-the north-west shearing is also recognized in the North of the Brévenne ophiolite in mylonitic zones at the base of the thrust [42]. This deformation is dated as pre-Early Visean (i.e. older than 345 Ma) by the Goujet unconformity. The syn- D2 MP/MT metamorphism is dated by the 40Ar/39Ar method on biotite, muscovite and amphibole at between 360 and 350 Ma [12,13,44]. This Early Carboniferous lineation must not be confused with another NW-SE stretching lineation, coeval with the emplacement of synkinematic Namurian-Westphalian plutons, formed during the syn-orogenic D4 event [24]. In the Monts du Lyonnais, southern Limousin or around the Guéret massif, a transpressive shearing, coeval with an amphibolite facies metamorphism, is dated between 350 Ma and 345 Ma by the syn-kinematic plutonism [3,10]. The significance of this event, however, remains poorly understood. In order to limit the number of events, it is considered here as a late- to post-D2.

3.4 The Middle Carboniferous (Visean) D3 event

The syn-metamorphic D3 deformation is only recognized in the southern part of the Massif Central, where the Cévennes and Albigeois par-autochthonous units experienced a first deformation at ca 340–335 Ma [9,27 and references therein]. Further south, southward-verging recumbent folds and thrusts of the Paleozoic series dated as Late Visean-Early Namurian (ca 325 Ma) by the syn-orogenic sediments of the foreland basin [23,30], are also related to the D3 event. This progressive southward younging of the nappe tectonics, coeval with the development of a flat-lying foliation and a north-south trending stretching lineation, has been compared to an Himalayan-style nappe stacking [45], but this model accounts only for the Visean tectonic evolution of the southern outer part of the belt. In the northern FMC, the Visean deformation develops under brittle conditions. In particular, the NW–SE stretching, related to dyke emplacement in the Tuff Anthracifères series is interpreted as the onset of the syn-orogenic extension [24,25].

3.5 The Late Carboniferous (Namurian-Westphalian) D4 event

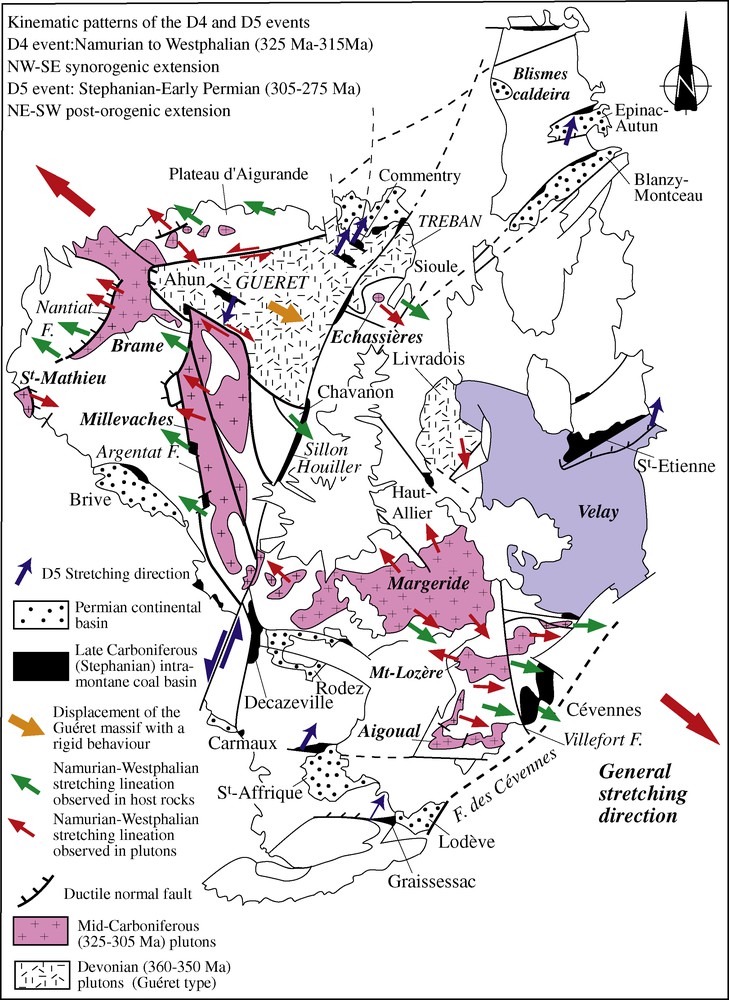

Ductile normal faults, such as the Argentat or Nantiat faults, coeval with granite emplacement, suggest an extensional emplacement for these plutons [24,25,58,59]. As shown by petrofabric and Anistropy of Magnetic Susceptibility (AMS) studies, most of the Late Carboniferous leucogranite and porphyritic monzogranite plutons and their metamorphic aureoles exhibit a well-defined NW–SE trending mineral or stretching lineation (Fig. 3) [63,64]. In such an extensional setting, the Sillon Houiller Fault should behave as a normal fault or tension gash used as a magma channel for the emplacement of some plutons [36]. The tectonic-plutonic D4 event, widespread in the entire FMC, is interpreted as a syn-orogenic extensional process, since at this time compression was still active in the northern and southern outer zones of Ardenne and Montagne Noire-Pyrénées, respectively.

Structural and kinematic map of the Late Carboniferous syn- and post-orogenic events (D4 and D5).

Fig. 3. Carte structurale et cinématique des événements extensifs syn- à post-orogéniques (D4 et D5) d’âge Carbonifère supérieur.

3.6 The Late Carboniferous (Stephanian) D5 extensional event

This last step in the structural evolution of the FMC can be distinguished from the previous one, as the maximum stretching direction trends NNE–SSW. The intramontane Stephanian coal basins developed either as half-grabens or left-lateral pull- aparts depending of the trend and kinematics of the fault that controls their opening and sedimentary infill (Fig. 3). At this time, the Sillon Houiller and the Argentat fault moved as brittle sinistral wrench faults. Except in the Velay dome and along some normal faults (e.g. Pilat, Graissessac) there is no documented ductile D5 deformation [22,39,43].

4 The crustal melting

A detailed presentation of the Variscan magmatism is beyond the scope of this paper; however, in addition to the voluminous plutonism that occupies nearly half of its area, the FMC experienced three stages of partial melting responsible for migmatites and anatectic granitoids.

The Devonian migmatites (Migmatite I) that crop out in the upper part of the UGU and in the LGU are dated between 385 Ma and 375 Ma [21,29]. They further developed from orthogneiss and paragneiss protoliths during the D1 event, and are related to the exhumation of the UGU rocks.

The Middle Carboniferous migmatites (Migmatite II), which are observed locally in the Montagne Noire, North Cévennes or South Millevaches (Fig. 1), are dated between 333 and 325 Ma [1]. The tectonic setting of these migmatites is still disputed. It has been proposed that the granite and migmatite of the axial zone of the Montagne Noire represent an extensional dome [65]; however, the structural evidence supporting a model as a metamorphic core complex is not convincing. Other tectonic settings such as an antiformal stack, transtension or diapirism have been proposed [22,43,48,62].

The Late Carboniferous melting (Migmatite III). This event, restricted to the Velay dome, is dated around 300 Ma [42 and enclosed references]. This anatexis is coeval with the opening of the St-Étienne coal basin and the ductile normal shearing of the Pilat fault.

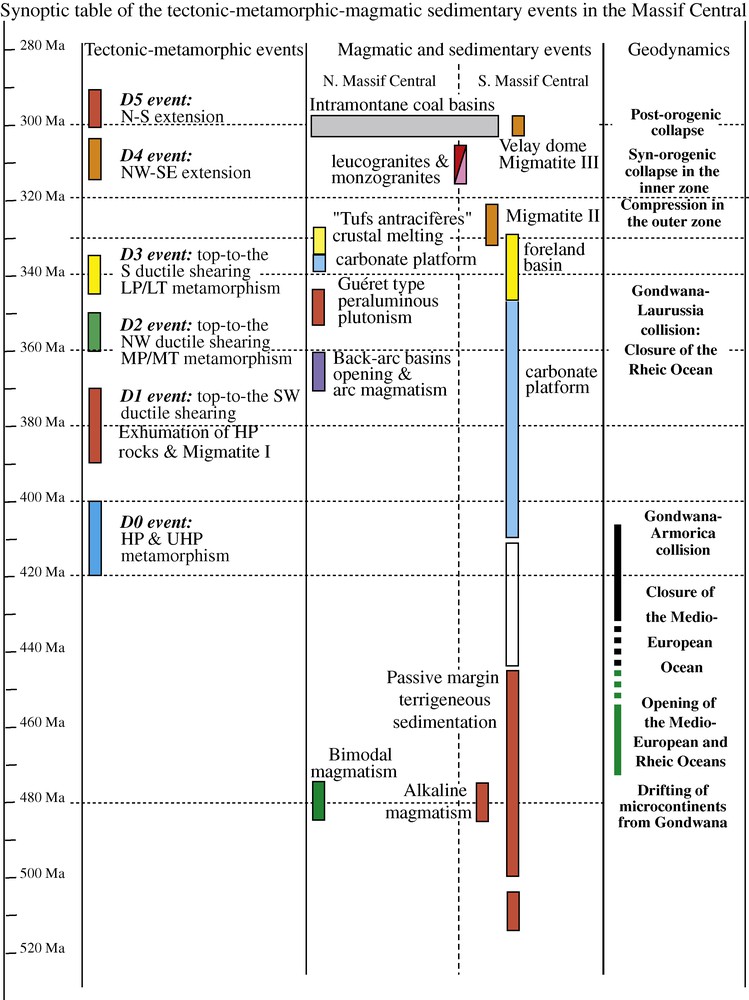

5 A tentative geodynamic evolution

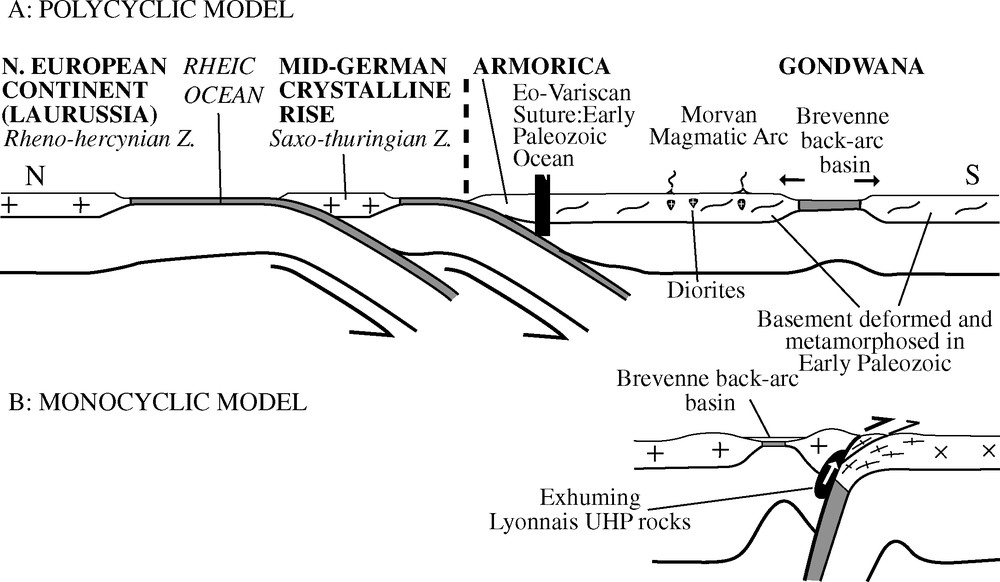

The events described above are variously interpreted, with two contrasting models. For some authors, the Massif Central formed throughout as with monocyclic evolution, characterized by a continuous north-directed subduction from the Silurian to the Carboniferous (Fig. 4) [38,46,47]. For other authors, the architecture of the FMC results from a polycyclic evolution with different senses of subduction and different times for closure of ocean basins [26,28,51,54]. In this second scheme, an Early Paleozoic “Eo-Variscan” cycle corresponds to the rifting of the Armorica microcontinent from Gondwana during the Ordovician to the Early Silurian, and its rewelding in Late Silurian-Early Devonian by northward subduction. The second, “Variscan” cycle, which represents the Late Devonian to Carboniferous collision of Gonwana and Laurussia, is accommodated by a south-directed subduction of the Rheic Ocean and related basins. Whatever the model, similar stages are recognized.

Synoptic chart of the sedimentary, tectonic, metamorphic and magmatic events in the French Massif Central.

Fig. 4. Tableau synoptique des événements sédimentaires, tectoniques, métamorphiques, et magmatiques du Massif central français.

In Cambrian-Ordovician times the rifting of several Gondwana-derived microcontinents such as Avalonia and Armorica took place. The widespread alkaline magmatism emplaced in the thinned crust of the Para-autochthonous unit, LGU and UGU supports this interpretation. The bimodal magmatism of the leptynite-amphibolite complex and the possible ophiolites of the UGU, correspond to the progressive crustal thinning that gave rise to the formation of the Medio-European Ocean separating the northern margin of Gondwana from Armorica. It is worth noting that such an oceanic area separating Armorica from the northern margin of Gondwana is not recorded by paleobiogeographic reconstructions [56]. This discrepancy between tectonics and paleogeographic approaches can be solved if one considers that the Medio-European Ocean was a short-lived, narrow domain of width less than 500 km.

From the Late Silurian to the Early Devonian, the Medio-European Ocean started to close by subduction below Armorica and the D0 event records evidence of this subduction. The FMC does not preserve any evidence of Eo-Variscan arc magmatism as it belongs to the lower plate. Traces of an Eo-Variscan arc can be recognized as olistoliths of calc-alkaline magmatic rocks enclosed in the St-Georges-sur-Loire block-in-matrix Unit in the Massif Armoricain [11,40]. The Devonian crustal melting observed in the UGU and LGU and the top-to-the-southwest ductile shearing event (D1) are coeval with the exhumation of the HP rocks [29].

The Middle to Late Devonian is a key period in the Variscan evolution, since it corresponds to the opening of the Brévenne oceanic basin and the formation of the Morvan arc (or Somme Unit). The calc-alkaline granodiorites, tonalites and gabbros of the so-called “tonalitic line of Limousin” [17,50] have been interpreted as the deep part of this magmatic arc, subsequently sheared during later tectono-metamorphic events [26]. In the monocyclic model, the Brévenne basin opened as a back arc-basin related to the northward subduction of the UGU [38], and the Morvan arc is not considered. In the polycyclic model, the Brévenne back-arc basin is associated with the Morvan arc and both elements belong to the upper plate above a southward subduction of the Rheic Ocean [28] (Fig. 5).

Two contrasted models accounting for the Late Devonian geodynamics. A. A polycyclic interpretation inspired by [28]. South-directed subduction is responsible for the closure of the Rheic Ocean and related oceanic basins and the final welding of Laurussia and Gondwana during the Early Carboniferous. In this model, the Brévenne basin represents a back-arc basin formed in response to the south-directed subduction, south of the Morvan magmatic arc. The arc developed upon a continental basement corresponding to the Upper Gneiss and Lower Gneiss Units. The Late Devonian subductions were preceded in the Silurian by a north-directed subduction followed by the collision of Armorica and Gondwana and the formation of the Eo-Variscan suture. Note that along a north–south profile in the eastern Massif Central, the Eo-Variscan suture is hidden below the Mesozoic Paris basin. B. A monocyclic interpretation redrawn from [38]. The structure of the French Massif Central results from a single north-directed subduction. In the Late Devonian, the opening of the Brévenne basin is coeval with the exhumation of the ultra high-pressure metamorphic rocks formed during the Silurian-early Devonian subduction. Note that in this monocyclic model, the Morvan magmatic arc is not considered.

Fig. 5. Deux modèles d’évolution géodynamique du Nord-Est du Massif central au Dévonien supérieur ; A. Interprétation polycyclique d’après [28]. Les subductions vers le sud sont responsables de la fermeture de l’océan Rhéique et de bassins océaniques associés, puis de la soudure finale des continents Laurussia et Gondwana au Carbonifère inférieur. Dans ce modèle, le bassin de la Brévenne représente un bassin d’arrière-arc associé à une subduction vers le sud, responsable de la formation de l’arc du Morvan. Cet arc se développe sur un substratum continental correspondant aux Unités supérieure et inférieure des Gneiss. Les subductions fini-dévoniennes ont été précédées au Silurien par une subduction vers le sud, suivie par la collision entre Armorica et Gondwana et la formation de la suture Éo-Varisque. Notez que sur une coupe subméridienne dans l’Est du Massif central, la suture Éo-Varisque est cachée sous les roches sédimentaires mésozoïques du Bassin de Paris. B. Interprétation monocyclique d’après [38]. La structure du Massif central résulte d’une seule subduction vers le nord. Au Dévonien supérieur, l’ouverture du bassin de la Brévenne est contemporain de l’exhumation des roches métamorphiques de ultrahaute pression, formées au cours de la subduction du Silurien au Dévonien inférieur. Notez que, dans ce modèle monocyclique, l’arc du Morvam n’est pas considéré.

The Late Devonian-Early Carboniferous D2 event remains the most enigmatic feature of the FMC. In the Limousin and Rouergue, the Thiviers-Payzac Unit was emplaced above the UGU with top-to-the north-west displacement. In the NE FMC, it might correspond to the closure of the Brévenne basin [42] Also, at the lithospheric scale, the D2 event might be related to the development of the Iberia-Armorica orocline. The end of the D2 event is marked by the emplacement of the first generation of peraluminous granitoids called Guéret-type plutons [3,10].

The Middle Carboniferous (Visean) records great differences in the tectonic regime between different areas of the FMC. In the southern part (Montagne Noire, Cévennes, Albigeois), the D3 event is responsible for the progressive crustal thickening of the outer zone. Conversely, in the northern part (North Limousin, Morvan), the Visean is characterized by platform limestone deposits followed by the “Tuffs anthracifères” episode of crustal melting. As already pointed out [24], the dominant NE–SW trend of the rhyolite and dacite dykes, interpreted as tension gashes, is in agreement with a NW–SE extensional setting. In the polycyclic model, the south-directed D3 shearing event is antithetic to the Rheic subduction.

In the Late Carboniferous (Namurian-Westphalian), the north–south shortening was completed in the Massif Central, but still continued in the northern and southern outer zones of the Variscan Belt, such as the Ardenne and Pyrénées, respectively. The FMC experienced a generalized syn-orogenic extensional regime characterized by ductile normal faulting (e.g. the Argentat or Nantiat faults) and the emplacement of synkinematic plutons. The D4 NW–SE stretching accommodates the syn-orogenic crustal “thinning” of the Variscan Belt.

Lastly, in the Late Carboniferous-Early Permian, a second extensional event developed. This event, which is widely observed in the FMC, represents a period of post-orogenic extension. The opening of the intramontane coal basins was controlled by brittle normal or wrench faults [22,24,41,43]. The Velay granitic-migmatitic dome is coeval with these post-orogenic extensional tectonics. At depth, the pervasive high-temperature granulite facies metamorphism of the lower crust, recorded in xenoliths of Neogene lavas, is probably a consequence of crustal thinning and decompression melting in the underlying mantle [43].

Acknowledgements

Scientific and editorial comments by M. Brown and an anonymous referee are kindly acknowledged.