1 Introduction

Most of the ophiolitic complexes studied in the eastern Tethyan regions (from Oman to Turkey) belong to the Upper Cretaceous belt, obducted onto the Gondwanian-Arabian margin (Peri-Arabic ophiolites of [30]). These pieces of oceanic lithosphere have been considered to be generated either at a mid-ocean ridge [9,13,19,27,44] or at spreading axis over an incipient subduction zone in the Neo-Tethyan Ocean [6,33,36]. In Iran, such ophiolites are present south of the Main Zagros Thrust (MZT; Fig. 1), in the Neyriz region (interpreted as resulting from very slow spreading, [3,16,26,31,34] at the foot of the Gondwanian margin [18]) and in the Kermanshah region, overlain by an Eocene volcanic arc [8]. These ophiolites are always in the same structural position, over of a pile of thrusted nappes including tectonic units from the distal part of the Gondwanian margin: “exotic blocks” (distal recifal constructions over alkaline volcanoes), radiolarian sheets (slope and basin units) and platform units. These ophiolites thus represent pieces of the southern part of the Tethyan oceanic lithosphere and tectonically associated with units issued from the slope and basins of the Gondwanian margin.

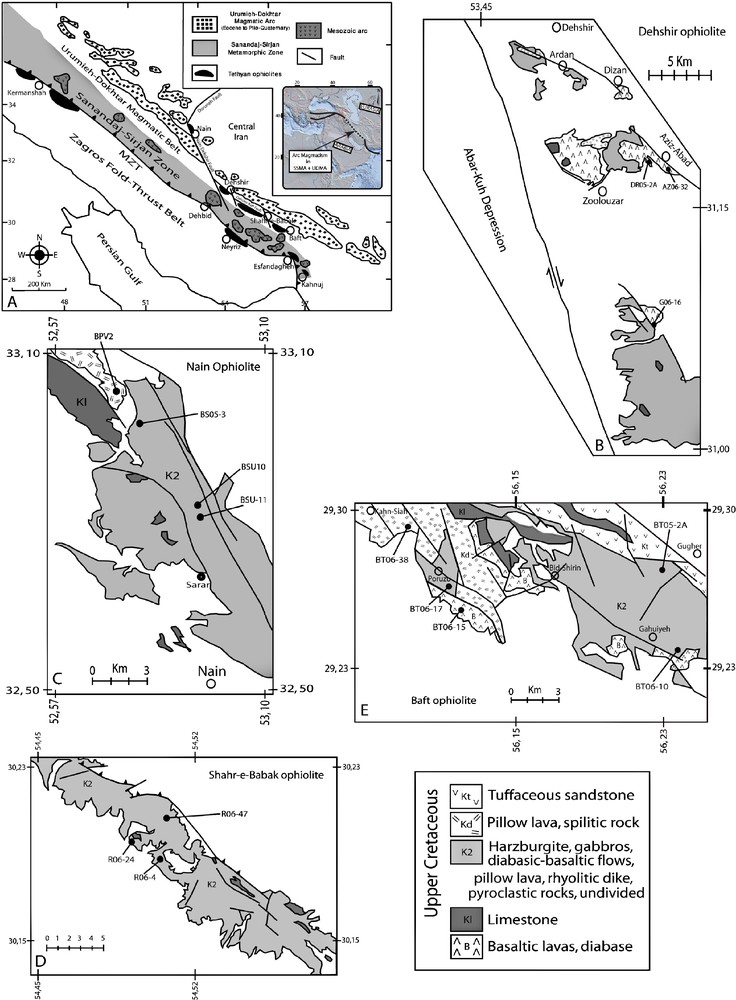

A. The schematic map showing the distribution of the Nain-Baft ophiolites, the Mesozoic ard of the Sanandaj-Sirjan zone and of the Urumieh-Dokhtar, Eocene-Plio-Quaternary magmatic arc. B, C, D, E. Simplified geological maps of the Dehshir, Nain, Shahr-e-Babak and Baft ophiolites respectively.

Carte géologique schématique montrant la distribution des ophiolites de Nain-Baft, l’arc mésozoïque de la zone de Sanandaj-Sirjan et l’arc magmatique Eocene-Plio-Quaternaire d’Umurieh Dokhtar. B, C, D, E. Cartes géologiques simplifiées, respectivement des ophiolites de Deshir, Nain, Shahr-e-Babak et Baft.

The subduction of the northern part of the Tethys (see [32] for references) is documented by arc magmatism (see [28] for references) from Upper Triassic to Lower Eocene crosscutting the Sanandaj-Sirjan Zone (SSZ) and from Upper Eocene to Plio-Quaternary in the Urumieh-Dokhtar Magmatic Zone (UDMZ), situated north of the SSZ. Is this subduction zone at a steady-state or submitted to variations in subduction velocity, dip and/or direction inducing alternation of extensive and compressive regimes in the arc and back-arc systems? South Iran is a key area to follow from Early Mesozoic up to Quaternary, the evolution of the active margin over the northern Tethyan subduction zone and try to answer these questions.

The central part of Iran, belonging to Mega-Lhasa-Iranian Block of Ricou [32] has been detached from the Gondwana in the Late Permian time giving birth to the Neo-Tethyan Ocean. It collides with Eurasia in the Middle Triassic time. The subduction jumped to the South of the Iranian block in the Late Triassic. The Sanandaj-Sirjan zone, situated at the South of the Central Iranian Block behaves from that time, as an active continental margin with a strong calc-alkaline magmatic activity [4,5,7,10–12,17,28,29,32,37–39]. This magmatism is composed of volcanic rocks and plutons from Upper Triassic to Early Eocene and Mesozoic [4,5,10–12,17,29] containing part of the ore deposit potential of Iran. First series of incipient back-arc basins of Upper Triassic to Lower Jurassic age are situated in the Esfandagheh and Kahnuj regions (Fig. 1). Moreover, the Central Iranian block is crosscut, north of the Sanandaj-Sirjan zone, by the Late Eocene-Plio-Quaternary Urumieh-Dokhtar Magmatic Arc (UDMA).

In the Late Eocene-Oligocene, the Arabian margin collided with the southern part of the Iranian block, along the Main Zagros Thrust. Since Oligocene, the Arabian margin subducted below the Sanandaj-Sirjan zone, pulled by the Tethyan oceanic lithosphere and gave rise to the UDMA. This subduction zone is affected in its central part (Qom to Baft) by a slab break-off marked by the presence of Quaternary adakites in that margin [17,28].

The purpose of this article is to show that the Nain-Baft ophiolitic belt represents a series of back-arc basins, opened in a transtensional regime in the Middle Cretaceous along the southern part of the Central Iranian block, behind the Mesozoic continental magmatic arc crosscutting the Sanandaj-Sirjan Zone.

2 Structure and nature of the different massifs

The Nain-Baft ophiolitic belt is composed of a series of massifs along the Nain-Dehshir and Dehshir-Baft strike-slip faults (Fig. 1A). Each massif shows a series of slices thrusted towards the south-west (Fig. 1B–E). These slices contain various proportions of harzburgites, gabbroic rocks, diabasic dikes, pillow lavas, andesites and rhyolites. Therefore, these ophiolites have been considered as highly dismembered and often characterized as a tectonic mélange [10,11]. Slicing probably resulted from transcompressional strike-slip movements along transcurrent faults separating the oceanic basins. However, some original contacts between the rock units are still preserved, allowing reconstruction of the original structure of these pieces of oceanic lithosphere (Fig. 2).

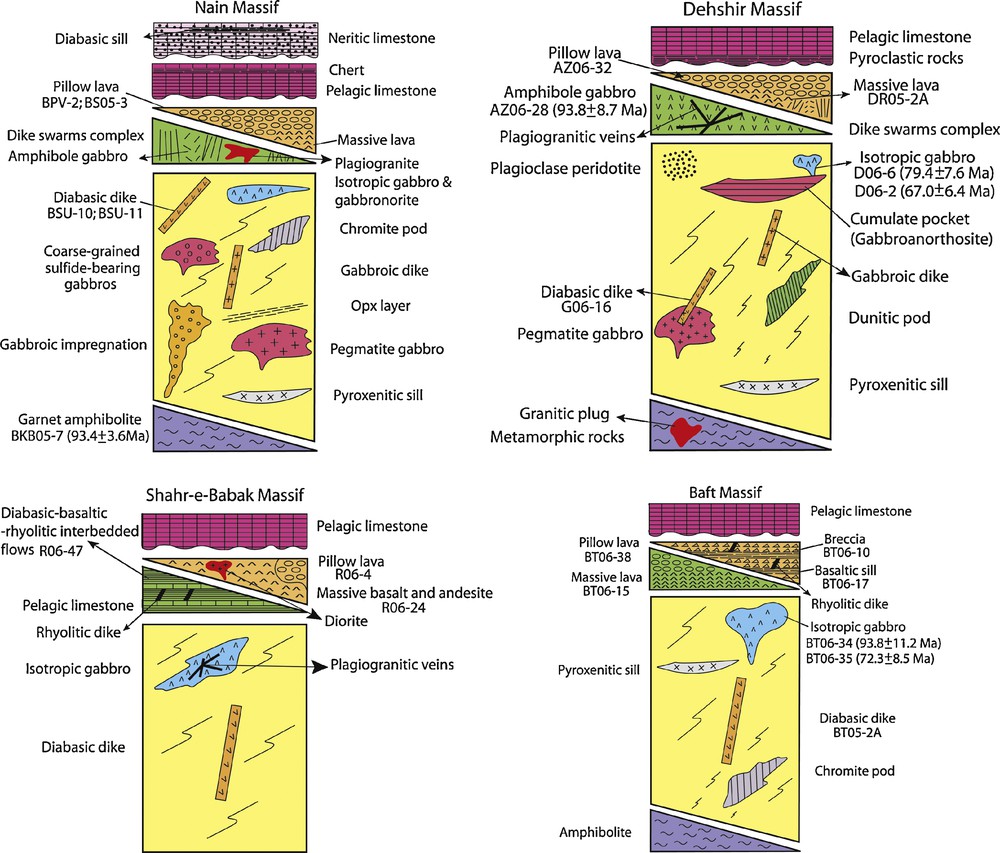

Restored stratigraphic column displaying idealized internal lithologic successions in the Nain-Baft ophiolites (not to scale). In these columns, the analyzed samples (whole rock and K-Ar age) have been shown for imaging the implication of ages, geochemical data and field geology.

Colonnes stratigraphiques reconstituées montrant les successions lithologiques dans les ophiolites de Nain-Baft (pas à l’échelle). Dans ces colonnes, les échantillons analysés (roches totales et datations K-Ar) sont indiqués pour montrer l’implication des âges, des données géochimiques et la géologie du terrain.

2.1 The Nain massif

The Nain ophiolite is the northern-most massif separated from the others by the Nain-Dehshir fault. It is composed of foliated moderately depleted harzburgites with minor lherzolites of secondary origin (impregnation of clinopyroxene). Slices of garnet amphibolites, containing leucocratic segregations resulting from its partial fusion are associated by tectonic contacts with mantle serpentinites. The structural position in regard to the mantle structures (high angle between the foliation in the peridotites and in the amphibolites and low pitch lineations) suggests that these metamorphic rocks result from transform movements.

All the mantle sequence contains pegmatitic gabbros, pyroxenite sills and is crosscut by isolated diabasic and gabbroic dikes. Coarse-grained gabbros, isotropic gabbros, diorites and gabbro-norites have been distributed as small-sized plutons within the mantle sequence (Fig. 2), sometimes with faulted contacts.

Diabasic dike swarm complex containing panels of plagiogranites and dacitic dikes is in tectonic contact with the mantle sequence (e.g. in Ahmad-Abad village) (Fig. 1C).

Slices of extrusive rocks are composed of pillow lavas and massive lavas (500 m thickness max.). Near the Ahmad-Abad or Farah-Abad villages, pelagic limestones containing chert levels are in stratigraphic contact with lavas. As these limestones are of Coniacian to Maastrichtian age [10], the extrusives of Nain are of Upper Cretaceous age. Neritic limestones of Middle Paleocene to Early Eocene age, containing diabasic sills, rest unconformably over the pelagic limestones with basal conglomerates and seal in some places the tectonic contacts between the slices.

2.2 The Dehshir massif

This massif is situated just at the intersection of the Nain-Dehshir and the Dehshir-Baft faults. The mantle sequence of the Dehshir massif is composed mainly of foliated plagioclase-bearing harzburgites, containing small pockets of pegmatitic and isotropic gabbros.

An ill-layered mafic-ultramafic cumulate sequence, composed of gabbros and clinopyroxenites, probably crystallized in a small magmatic reservoir within the peridotites (Fig. 2). Isolated gabbroic and diabasic dikes crosscut the peridotites.

Metamorphic rocks, including actinolite schists, amphibolites, slates and marbles, crosscut by acidic plugs, show faulted contacts with peridotites near the Zolouzar village.

Slices of amphibole gabbros with plagiogranitic dikelets, near the Ahmad-Abad village, are in faulted contacts with slices containing a pile of volcanic rocks composed of pillow lavas grading upwards to pyroclastic materials. Basaltic to dacitic dikes crosscut the volcanic sequence and form in some slices dike swarms (Figs. 1B and 2).

Upper Cretaceous pelagic limestones (Globotruncana) rest stratigraphically upon the volcanic pile for example near the Ardan village (Fig. 1B), showing that the extrusives of Dehshir massif are again of Upper Cretaceous age.

2.3 The Shahr-e-Babak massif

The mantle sequence of the Shahr-e-Babak ophiolite is characterized by the presence of foliated harzburgites crosscut by diabasic dikes and small-sized lenses of isotropic gabbros (Fig. 2). Plagiogranitic veins commonly crosscut the isotropic gabbros, for example at the north of the Khabr village.

The volcanic sequence is composed of basalts, andesites and rhyolites. These lavas are interbedded flows with pelagic limestones containing cherts which deliver a Campanian to Maastrichtian stratigraphic age (new data). Rhyolitic dikes crosscut andesites and basalts near the Chah-Bagh village (Fig. 1D). Massive basaltic and pillow lavas are situated at the top of the volcanic sequence. Shallow dioritic plutons, containing andesitic-basaltic xenoliths near the contacts, have been injected into the massive lavas.

The volcanic pile in the Shahr-e-Babak ophiolite is stratigraphically overlain by a Coniacian to Maastrichtian pelagic limestones [12]. Here again, the stratigraphic age of the extrusive rocks is Upper Cretaceous.

2.4 The Baft massif

This southern-most massif contains slices of mantle sequence, composed of foliated depleted harzburgites, crosscut by abundant diabasic dikes. Isotropic gabbros as small-sized plutons associated with pyroxenitic sills are widespread throughout the mantle sequence, sometimes with faulted contacts, as near the Bedeshk village (Fig. 2).

Slices of volcanic rocks in the Baft complex, in faulted contact with the peridotites in the Tituiyeh village, are composed of basaltic to andesitic massive and pillow lavas, (Fig. 1E). Pyroclastic volcanic rocks, including tuffs and volcanic breccias, alternating with basaltic sills, are common in the massif. Andesitic and basaltic fragments constitute the main proportion of these breccias. Rhyolitic dikes crosscut the breccias near the Kahn-Siah village. Cenomanian to Maastritchian pelagic limestones overly the extrusive sequence.

2.5 Summary of geological data

In summary, these ultrabasic-basic assemblages of the Nain-Baft belt do not correspond to any of the ophiolites obducted as nappes thrusted onto the gondwanian margin and of course to the 1972 Penrose definition of ophiolites. They are highly sliced and dismembered. They exhibit foliated depleted plagioclase to spinel harzburgitic mantle sequence, marked locally by melt percolations (as clinopyroxene impregnations) through the peridotites. No real layered cumulate sequence was found over the mantle section of these massifs. However, isotopic gabbros and basic cumulates are present within dikes, sills and small to medium size pockets within the peridotites. No real sheeted dike complex is observed. Isolated dikes to separated dike swarms are locally found within the mantle harzburgites or in tectonic slices. They testify to a slow spreading regime with a low extraction rate of liquids from the mantle. The extrusive rocks are highly variable from one massif to the other: basaltic pillow, andesites, dacites, rhyolites and associated pyroclastites. The conformably pelagic limestones over or interstratified in the extrusive lavas testify to their Cenomanian to Coniacian age.

3 Petrography of the lavas

The mafic lavas in the Nain ophiolite are characterized by occurrences of pillow lavas and diabasic dikes. Clinopyroxene (Wo30-42En56-47Fs10-13), plagioclase (An71-73) and chloritized amphiboles (actinolitic hornblende to magnesio-hornblende) associated with plagioclase microlites are the main constituents of the mafic lavas.

In Dehshir ophiolites, the mafic lavas are characterized by the presence of pillow lavas, diabasic dikes and massive lava flows. Clinopyroxene (Wo35-45En51-40Fs12-15) and highly albitized (Ab86-99) plagioclases are the main rock-forming minerals of the lavas.

Magmatic rocks, in the Shahr-e-Babak ophiolites, are dominated by the occurrence of pillow lavas, basaltic flows or sills, rhyolites, andesites and trachy-andesites. Plagioclase and clinopyroxene phenocrysts (Wo38-45En44-47Fs10-14) along with plagioclase microlites are the main primary constituents of the mafic lavas. Pargasite is the other rock-forming phase, segregated between the plagioclase and augite grains. Hornblende, plagioclase (An15-16) and diopside (Wo43-46En41-45Fs10-13) are present in andesites. Rhyolites are characterized by spherulitic intergrowth of fine-grained quartz and albite microlites.

In addition to pillow lavas and diabasic dikes, volcanic breccias with basaltic-andesitic fragments, alternating with basaltic sills are dominant in the Baft ophiolites. The basaltic-andesitic rocks consist of uralitized clinopyroxenes (Wo41-43En40-41Fs17-18), minor amounts of orthopyroxene (Wo4-7En65-53Fs31-40) and plagioclases. Plagioclases form lath-shaped phenocrysts with oscillatory zoning (An41-91) and/or groundmass microlites.

4 Geochemistry of the lavas

Using the LOI versus Na2O and SiO2 diagrams (not shown), we selected the samples with less than 4% LOI to avoid, as far as possible, alteration effect. In the Na2O + K2O versus SiO2 diagram [22], most mafic lavas (pillow lavas, basaltic massive lavas, diabasic dikes and the basaltic fragments in breccia) show basaltic and basaltic andesitic compositions (in Table 2). The exceptions are two pillow lavas from the Dehshir (61.5 SiO2 %wt.) and the Baft (60.8 SiO2%wt.) ophiolites, with andesite and trachy-andesite compositions.

Analyse de roches totales représentatives des laves mafiques de la ceinture ophiolitique de Nain-Baft (DD : dyke de diabse ; PL : laves de coussin ; ML : coulées de laves massives ; BF : fragments de basalte dans des brèches ; BS : sill de basalte). Les analyses chimiques de roches totales ont été effectuées au Centre de géochimie de la surface (Strasbourg, France) et calibrées par des standards internationaux. Les éléments majeurs et Ni, Cr, V, Sc, Y, Zr, Ba, Sr ont été mesurés par ICP-AES et les autres éléments en trace, dont les terres rares, par ICP-MS.

| Sample | G06-16 | AZ06-32 | DR05-2A | BT06-10 | BT06-15 | BT06-17 | BT06-38 | BT05-2A | R06-4 | R06-47 |

| Locality | Dehs. | Dehs. | Dehs. | Baft | Baft | Baft | Baft | Baft | Sh.Bab | Sh.Bab |

| Rock | DD | PL | ML | BF | ML | BL | PL | DD | PL | BS |

| SiO 2 | 52.2 | 61.5 | 51 | 55.1 | 49.4 | 54.4 | 60.8 | 52.7 | 53.2 | 47.1 |

| TiO 2 | 0.822 | 0.500 | 1.81 | 0.607 | 0.503 | 0.884 | 0.669 | 0.776 | 0.738 | 0.865 |

| Al 2 O 3 | 15.0 | 15.5 | 12.2 | 18.2 | 19.0 | 14.7 | 16.0 | 15.9 | 13.5 | 17.8 |

| FeO t | 10.6 | 6.84 | 13.1 | 8.22 | 6.87 | 11.3 | 7.85 | 6.99 | 7.42 | 11.5 |

| MnO | 0.173 | 0.197 | 0.244 | 0.156 | 0.145 | 0.159 | 0.218 | 0.111 | 0.149 | 0.183 |

| MgO | 4.75 | 1.53 | 6.82 | 3.11 | 4.34 | 5.87 | 1.28 | 5.67 | 2.67 | 5.04 |

| CaO | 8.22 | 6.76 | 6.98 | 8.34 | 9.02 | 6.20 | 2.54 | 8.7 | 13.1 | 6.03 |

| Na 2 O | 5.20 | 4.58 | 3.73 | 3.34 | 3.32 | 3.59 | 8.96 | 5.12 | 4.31 | 4.34 |

| K 2 O | 0.816 | 0.042 | 0.88 | 0.25 | 1.68 | 0.960 | 0.378 | 0.29 | 0.612 | 2.90 |

| P 2 O 5 | 0.040 | 0.087 | 0.24 | 0.160 | 0.063 | 0.125 | 0.246 | 0.16 | 0.054 | 0.362 |

| LOI | 1.03 | 1.66 | 1.47 | 1.06 | 4.74 | 2.32 | 1.22 | 2.37 | 4.44 | 3.05 |

| Total | 98.95 | 99.17 | 98.5 | 98.55 | 99.09 | 100.48 | 100.16 | 98.82 | 100.16 | 99.09 |

| La | 1.04 | 3.78 | 7.48 | 12.2 | 1.36 | 3.65 | 6.49 | 6.42 | 1.93 | 19.2 |

| Ce | 3.64 | 9.03 | 21.4 | 24.6 | 3.44 | 8.75 | 14.8 | 13.9 | 5.92 | 38.5 |

| Pr | 0.691 | 1.45 | 3.44 | 3.11 | 0.588 | 1.39 | 2.36 | 1.85 | 1.03 | 5.00 |

| Nd | 4.01 | 7.33 | 17.8 | 12.6 | 3.19 | 7.06 | 12.0 | 8.51 | 5.58 | 20.8 |

| Sm | 1.65 | 2.30 | 6.09 | 2.92 | 1.30 | 2.26 | 3.48 | 2.31 | 1.77 | 4.51 |

| Eu | 0.599 | 0.869 | 1.8 | 0.858 | 0.467 | 0.808 | 1.270 | 0.826 | 0.672 | 1.237 |

| Gd | 2.086 | 2.59 | 6.99 | 2.85 | 1.66 | 2.37 | 4.055 | 2.77 | 1.89 | 4.078 |

| Tb | 0.468 | 0.531 | 1.29 | 0.452 | 0.280 | 0.497 | 0.703 | 0.495 | 0.373 | 0.588 |

| Dy | 3.17 | 3.42 | 9.14 | 2.69 | 1.99 | 3.61 | 4.64 | 3.38 | 2.82 | 3.47 |

| Ho | 0.772 | 0.857 | 2.12 | 0.602 | 0.516 | 0.822 | 1.06 | 0.777 | 0.602 | 0.692 |

| Er | 2.12 | 2.34 | 5.66 | 1.69 | 1.35 | 2.26 | 2.94 | 2.15 | 1.70 | 1.76 |

| Tm | 0.376 | 0.418 | 0.878 | 0.285 | 0.239 | 0.387 | 0.495 | 0.351 | 0.278 | 0.271 |

| Yb | 2.23 | 2.41 | 5.5 | 1.67 | 1.41 | 2.35 | 3.04 | 2.09 | 1.58 | 1.65 |

| Lu | 0.341 | 0.376 | 0.869 | 0.252 | 0.223 | 0.351 | 0.433 | 0.345 | 0.238 | 0.231 |

| Sc | 24.5 | 16.9 | 43 | 20 | 32 | 40.5 | 32 | 32 | 26.1 | 29 |

| V | 297 | 98.1 | 363 | 160 | 254 | 358 | 144 | 220 | 323 | 265 |

| Cr | 14.1 | 6.12 | 79 | 5 | 138 | 9.95 | - | 23 | 23.3 | - |

| Ni | 36.0 | 4.89 | 51 | 12 | 55 | 23.3 | 6 | 36 | 26.2 | 10 |

| Cs | 0.107 | 0.078 | 0.099 | 9.53 | 0.577 | 0.146 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.141 | 0.005 |

| Rb | 7.51 | 0.312 | 9.34 | 9.84 | 21.9 | 9.19 | 2.96 | 2.57 | 6.37 | 38.4 |

| Ba | 27.3 | 13.4 | 236 | 503 | 168 | 97.2 | 57 | 27 | 30.6 | 604 |

| Sr | 211 | 288 | 143 | 661 | 202 | 250 | 299 | 176 | 112 | 514 |

| Y | 21.8 | 23.4 | 56 | 17 | 13 | 23.2 | 29 | 21 | 16.6 | 18 |

| Zr | 33.2 | 50.2 | 185 | 87 | 26 | 51.5 | 54 | 72 | 41.0 | 78 |

| Hf | 1.18 | 1.64 | 4.81 | 2.23 | 0.803 | 1.50 | 1.72 | 1.84 | 1.12 | 1.89 |

| Nb | 0.346 | 1.290 | 4.84 | 2.05 | - | 2.04 | 1.03 | 6.35 | 0.514 | 3.74 |

| Ta | 0.031 | 0.094 | 0.376 | 0.198 | 0.020 | 0.141 | 0.077 | 0.467 | 0.038 | 0.197 |

| Pb | 0.404 | 1.53 | 2.52 | 11.8 | - | 2.47 | 1.75 | 1.69 | 1.27 | 3.73 |

| Th | 0.085 | 0.609 | 0.473 | 3.04 | 0.040 | 0.470 | 0.980 | 1.1 | 0.171 | 4.18 |

| U | 0.055 | 0.423 | 0.207 | 0.885 | 0.107 | 0.167 | 0.194 | 0.358 | 0.115 | 1.18 |

| Sample | R06-24 | BPV2 | BS05-3 | BSU-10 | BSU-11 | |||||

| Locality | Sh.Bab | Nain | Nain | Nain | Nain | |||||

| Rock | ML | PL | PL | DD | DD | |||||

| SiO 2 | 47.4 | 49.4 | 49.1 | 46.3 | 54.2 | |||||

| TiO 2 | 0.637 | 0.329 | 0.797 | 0.491 | 0.84 | |||||

| Al 2 O 3 | 16.0 | 16.5 | 15.3 | 12.1 | 12.8 | |||||

| FeO t | 10.6 | 10.2 | 7.69 | 6.66 | 9.38 | |||||

| MnO | 0.148 | 0.172 | 0.139 | 0.158 | 0.191 | |||||

| MgO | 9.71 | 5.4 | 7.54 | 8.71 | 7.46 | |||||

| CaO | 9.23 | 9.64 | 13.6 | 22 | 8.15 | |||||

| Na 2 O | 2.78 | 3.75 | 2.51 | 0.198 | 4.2 | |||||

| K 2 O | 0.603 | 0.84 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.342 | |||||

| P 2 O 5 | 0.064 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.075 | 0.093 | |||||

| LOI | 2.46 | 2.66 | 1.86 | 2.62 | 2.05 | |||||

| Total | 99.62 | 98.89 | 98.9 | 99.3 | 99.63 | |||||

| La | 1.87 | 1.86 | 2.31 | 0.764 | 2.31 | |||||

| Ce | 5.20 | 6.11 | 6.03 | 2.17 | 5.96 | |||||

| Pr | 0.881 | 1.12 | 1.04 | 0.408 | 1 | |||||

| Nd | 4.61 | 6.39 | 5.67 | 2.46 | 5.46 | |||||

| Sm | 1.64 | 2.43 | 2.05 | 1.1 | 1.95 | |||||

| Eu | 0.643 | 0.946 | 0.828 | 0.398 | 0.723 | |||||

| Gd | 1.80 | 3.24 | 2.67 | 1.29 | 2.17 | |||||

| Tb | 0.345 | 0.622 | 0.475 | 0.234 | 0.428 | |||||

| Dy | 2.68 | 4.49 | 3.39 | 2.43 | 3.23 | |||||

| Ho | 0.612 | 1.09 | 0.826 | 0.544 | 0.721 | |||||

| Er | 1.68 | 2.88 | 2.11 | 1.48 | 2.01 | |||||

| Tm | 0.281 | 0.474 | 0.334 | 0.248 | 0.344 | |||||

| Yb | 1.56 | 2.77 | 2.26 | 1.47 | 2.02 | |||||

| Lu | 0.231 | 0.46 | 0.339 | 0.223 | 0.292 | |||||

| Sc | 36.6 | 43 | 37 | 28.2 | 33 | |||||

| V | 275 | 288 | 228 | 179 | 263 | |||||

| Cr | 65.5 | 194 | 331 | 238 | 192 | |||||

| Ni | 35.6 | 61 | 119 | 82.1 | 61.9 | |||||

| Cs | 0.253 | 0.386 | 0.114 | ND | 0.172 | |||||

| Rb | 5.47 | 14.6 | 4.19 | 0.13 | 3.35 | |||||

| Ba | 100 | 145 | 25 | 5.63 | 20.1 | |||||

| Sr | 179 | 302 | 112 | 81.4 | 252 | |||||

| Y | 15.1 | 28 | 21.1 | 15.5 | 19.4 | |||||

| Zr | 26.8 | 67 | 50.3 | 20.8 | 35 | |||||

| Hf | 0.914 | 1.82 | 1.48 | 0.72 | 1.18 | |||||

| Nb | 0.517 | 1.07 | 1.93 | 0.179 | 0.505 | |||||

| Ta | 0.036 | 0.08 | 0.161 | 0.357 | 0.039 | |||||

| Pb | 3.88 | 3.68 | 1.6 | 1.16 | 4.66 | |||||

| Th | 0.263 | 0.09 | 0.186 | 0.05 | 0.371 | |||||

| U | 0.434 | 0.056 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

On the basis of trace element composition, Th-Hf-Nb diagram of [45], the Nain mafic lavas fall in the arc tholeiitic field and in the N-MORB one, whereas mafic lavas of the Dehshir, the Shahr-e-Babak and the Baft ophiolites plot both in the arc tholeiites and the calc-alkaline fields. The most striking feature of this diagram is the strong calc-alkaline signature of the Baft and Shahr-e-Babak lavas.

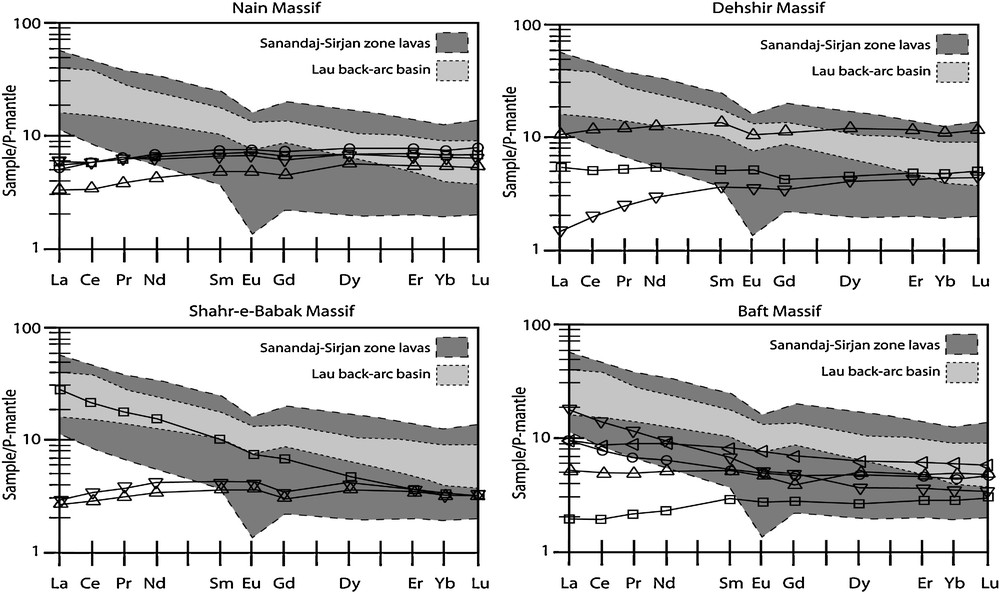

The REE primitive-mantle normalized patterns for mafic rocks show both flat to slightly depleted LREE trends (between N and T-MORBs with La(N)/Sm(N) = 0.4–1.3 and La(N)/Yb(N) = 0.3–1.6) and LREE enriched profiles (calc-alkaline series with La(N)/Sm(N) = 1.8–3 and La(N)/Yb(N) = 2.7–8.3). In the Shahr-e-Babak massif, the calc-alkaline lavas alternate with the tholeiitic ones. The similarity and position of the patterns, from the primitive lavas in the lower part of the diagrams to the more evolved lava profiles in the upper part, suggest a magma evolution by fractional crystallization (Fig. 3). Otherwise, flat or LREE depleted patterns account for different degrees of partial fusion of the mantle source.

Primary mantle normalized REE diagrams for the Nain-Baft mafic lavas. For comparison, the basaltic glasses from the Lau basin [14] and the volcanic rocks of the Mesozoic arc from the Sanandaj-Sirjan [28] are presented. Normalizing values are from [40].

Diagramme de terres rares normalisées au manteau primitif des laves de Nain-Baft. Les compositions des verres basaltiques du bassin de Lau [14] et celles des laves de l’arc mésozoïque de la zone de Sanadaj-Sirjan [28] sont données par comparaison. Les valeurs de normalisation sont de [40].

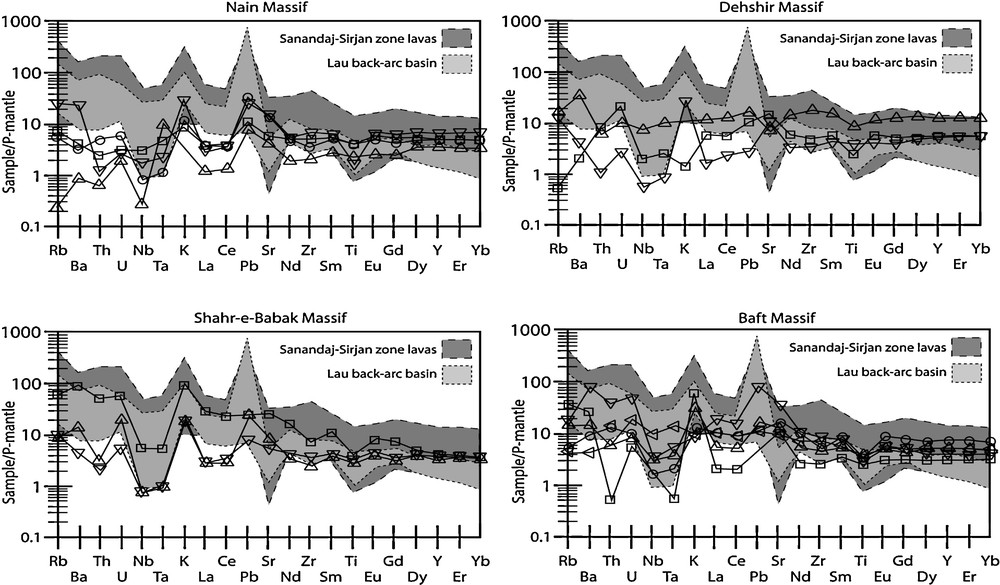

Based on the primary-mantle normalized multi-elementary diagrams for the lavas (Fig. 4), in the Nain-Baft suture, Nb and Ta negative anomalies and large ion lithophile elements (LILE such as K, Pb, U, Ba, Rb and Th) positive anomalies are characteristic of calc-alkaline series. Ti in these samples exhibits none to slight negative anomalies. The presence of interlayered tholeiitic and calc-alcaline lavas is characteristic of a back-arc environment.

Primary mantle normalized multi-elements diagrams for the Nain-Baft mafic lavas. For comparison, the basaltic glasses from the Lau basin [14] and the volcanic rocks of the Mesozoic arc from the Sanandaj-Sirjan [28] are presented. Normalizing values are from [45].

Diagramme multiélémentaire normalisé au manteau primitif des laves de Nain-Baft. Les compositions des verres basaltiques du bassin de Lau [14] et celles des laves de l’arc mésozoïque de la zone de Sanadaj-Sirjan [28] sont données par comparaison. Les valeurs de normalisation sont de [40].

The Nain-Baft mafic lavas have been compared with basaltic lavas dredged in the back-arc Lau basin [14] and with the lavas of the Mesozoic arc crosscutting the Sanandaj-Sirjan zone. Compared with the Lau basin, the lavas from the Nain-Baft ophiolitic belt exhibit more depleted REE patterns. The Nain-Baft lavas reveal moderate LILE and HFSE anomalies as compared to those of the Lau basin. This suggests the Nain-Baft lavas melt from a mantle, not significantly influenced by fluids issued from the subducting slab. Calc-alkaline mafic rocks from the Shahr-e-Babak and Baft ophiolites show similar enrichment and depletion with the lavas from the Mesozoic arc of the Sanandaj-Sirjan zone, but with lower contents in incompatible elements and slight Ti and Sr anomalies.

As concluding remarks, the mafic rocks from the Nain-Baft ophiolitic belt are geochemically characterized by both arc-tholeiitic to true calc-alkaline affinities, marked particularly by slight enrichment in LILE and depletion in HFSE, generally found in back-arc environment.

It is noteworthy that these geochemical signatures, characterized by LILE enrichment and HFSE depletion is consistent with melting from a mantle source influenced by the fluids flowing from a subducting slab [23,35,41]. Upwelling of such a mantle modified by fluids, beneath a back-arc basin, is only compatible with a spreading rate over the subduction zone at least of 3 cm/yr [21].

5 Constraints on ages

Although the transgressive limestones onto the Nain-Baft extrusive rocks are all Upper Cretaceous, they are not exactly of the same age. The first sediments deposited on the lavas are dated from Coniacian in the Nain, Dehshir and Shahr-e-Babak [10] and from Cenomanian in the Baft massif [12]. It would suggest that the Baft extrusives rocks are slightly older than the other ones. The pelagic limestones interlayered with the basaltic-rhyolitic lava flows in the Shahr-e-Babak massif deliver a stratigraphic age of Campanian.

To date the plutonic sequence, six samples from gabbros (magmatic amphiboles) and amphibolites (metamorphic amphiboles) have been selected. All selected gabbros are geochemically arc-tholeiites. The results of classical 40K-40Ar datings on amphiboles are presented below. Results that could be interpreted as isotopic closure ages [24,43] are listed in Table 1. The ages on amphibole from gabbros and amphibolite range from 93.8 Ma (Cenomanian) to 67.0 Ma (Maastritchian) to. The most reliable age (high content in K2O and 40Ar; high ratio in radiogenic Ar content) of 93.4 Ma (Cenomanian) is given by amphiboles in a amphibolite of the Nain massif. In the Deshir massif, one sample delivers again the same age but with lower content in K2O and 40Ar and low ratio in radiogenic Ar content. Two other samples from the same intrusion gave two different younger ages 79.4 to 67.0 which could not be very different, regarding the errors bars (Campanian-Maastritchian). In the Baft massif, again amphiboles of two samples (with very low content in K2O) within gabbros yielded two different ages. One is again 93.8 Ma (Cenomanian) and the second is 72.3 Ma (Campanian). These isotopic datings are completely compatible with the stratigraphic age of the limestones resting upon the extrusive rocks (Table 2).

Âges K-Ar des gabbros et amphibolites de la ceinture de Nain-Baft, mesurés à l’École et observatoire des sciences de la Terre (Strasbourg), suivant la méthode décrite par [24].

| Samples | Locality | Rock type | Mineral | K2O (wt.%) |

|

rad.40Ar (10-11 mol/g) | Age (± 2σ) in Ma |

| BKB 05-7 | Nain | Amphibolite | Amphibole | 0.572 | 30.7 | 7.893 | 93.4 ± 3.6 |

| AZ 06-28 | Dehshir | Gabbro (arc tholeiite) | Amphibole | 0.138 | 7.9 | 1.913 | 93.8 ± 8.7 |

| D 06-6 | Dehshir | Gabbro (arc tholeiite) | Amphibole | 0.126 | 9.7 | 1.472 | 79.4 ± 7.6 |

| D 06-2 | Dehshir | Gabbro (arc tholeiite) | Amphibole | 0.118 | 10.0 | 1.160 | 67.0 ± 6.4 |

| BT 06-35 | Baft | Gabbro (arc tholeiite) | Amphibole | 0.089 | 12.0 | 0.945 | 72.3 ± 8.5 |

| BT 06-34 | Baft | Gabbro (arc tholeiite) | Amphibole | 0.084 | 14.5 | 1.165 | 93.8 ± 11.2 |

In conclusion, we tentatively propose to retain 93 Ma (Cenomanian) as a meaningful geological age, i.e., the approaching the time of formation of the plutonic rocks and oceanic metamorphism. The dispersion to youger age results probably from a mixing of the amphiboles in separated samples (coexistence of primary hornblende with secondary actinolite which is known to retain poorly radiogenic argon). One should remark that similar ages were obtained for the Oman ophiolites both on metamorphic soles [25] and plutonic sequence [42].

Neritic limestones of Middle Paleocene age rest unconformably over the tectonic contacts of these ophiolitic slices. These sediments sealed the closure of the Nain-Baft back-arc basins. Therefore, this back-arc spreading was short-lived, lasting at maximum 45 Ma from Cenomanian to Paleocene.

6 Interpretations and conclusions

Field and geochemical studies reveal that the massifs of the Nain-Baft ophiolitic belt, besides some differences, possess common characteristics. All of them exhibit slices composed of: mantle harzburgites, sometimes associated with amphibolites as marker of transform faults, isotropic to few poorly layered cumulative gabbros in small reservoirs together with gabbroic and pyroxenite dikes and sills within the mantle sequence, dike swarms, extrusive rocks from basalts to rhyolites, Upper Cretaceous limestones on the top of the lavas. The geochemistry of the lavas shows tholeiitic to arc-affinities. The geological setting, the ages of the massifs, the differences between the massifs, marked essentially by the relative importance of the components listed above and the geochemistry of the lavas led us to consider the existence of several back-arc basins, separated from each other by strike-slip faults, reactivated at present time, in the southern margin of the Iranian block. These short-lived back-arc basins (Cenomanian-Maastritchian) were situated north of the Upper-Jurassic to Cretaceous magmatic arc crosscutting the Sanandaj-Sirjan Zone (Fig. 5B), of the Albian exhumed high-pressure metamorphic rocks in the Esfandagheh region [1] and of Upper Triassic to Lower Jurassic Esfandagheh marginal and back-arc basins (Soghan, Sikhoran and Kahnuj complexes [2,15,20]) (Fig. 5A, B). Large strike-slip movements, inducing trans-tensional openings of these Cretaceous back-arc basins are the result of the oblique subduction of the northern part of the Tethyan Ocean [32]. Opening and closure of the Nain-Baft back-arc basins are contemporaneous with the intra-oceanic thrusting and obduction onto the Gondwanian margin of the Peri-Arabic ophiolitic nappes (Oman, Neyriz, Kermanshah, Turkish ophiolites; Fig. 5B, C).

Series of cross-sections since Upper Triassic time with emphasis on the evolution of the Nain-Baft oceanic back-arc basin (dashed line is the lithosphere [L]-asthenosphere [A] boundary) A. During Upper Trias to Lower Cretaceous, the presence of the Mesozoic magmatic arc (figured as Arc 1) and the Esfandagheh marginal basins in the active margin of the central Iranian block was related to the subduction of Neo-Tethyan ocean beneath the Iranian block. B. In Upper Cretaceous, intra-oceanic thrusting took place to the South of the Tethyan ocean as to the North, erosion of the Upper Triassic-Lower Cretaceous arc, migration of the Mesozoic magmatic arc toward north (figured as Arc2) and opening of the oceanic transtensional Nain-Baft marginal basin occurred within the Iranian block. C. Maastrichtian-Paleocene is the time of obduction of the Neyriz ophiolites onto the Gondwana margin and closure of the Nain-Baft basin. D. Late Eocene-Miocene final collision between the Arabian plate and the Iranian block (through Main Zagros Thrust = MZT) along with emplacement of the plutonic and volcanic rocks of the Urumieh-Dokhtar Magmatic Belt (UDMB figured as Arc 3) are related to the Eocene-Miocene movements. Masquer

Series of cross-sections since Upper Triassic time with emphasis on the evolution of the Nain-Baft oceanic back-arc basin (dashed line is the lithosphere [L]-asthenosphere [A] boundary) A. During Upper Trias to Lower Cretaceous, the presence of the Mesozoic magmatic arc ... Lire la suite

Séries de coupes depuis le Trias pour montrer l’évolution du bassin arrière-arc océanique de Nain-Baft (les pointillés représentent la limite lithosphère [L]-asthénosphère [A]). A. Pendant le Trias supérieur et le Crétacé inférieur, la présence de l’arc magmatique mésozoïque (représenté par l’Arc 1) et des bassins marginaux d’Esfandagheh dans la marge active du bloc de l’Iran central est reliée à la subduction de la Néo-Téthys sous le bloc iranien. B. Pendant le Crétacé supérieur, le charriage intra-océanique s’effectue au Sud de l’océan téthysien comme vers le Nord, et se produisent l’érosion de l’arc du Trias supérieur-Crétacé inférieur la migration de l’arc vers le nord (représenté par l’Arc 2) et l’ouverture dans le continent iranien du bassin marginal en transtension arrière-are de Nain-Baft. C. Obduction des ophiolites de Neyriz sur la marge du Gondwana et fermeture du bassin de Nain-Baft au Maastrichtien-Paléocène. D. Collision finale Eocène terminal-Miocène entre la plaque Arabique et le bloc Iranien (MZT–Main Zagros Thrust), et l’emplacement des roches plutoniques et volcaniques de la ceinture magmatique d’Urumieh-Dokhtar (UDMB, représenté par l’Arc). Masquer

Séries de coupes depuis le Trias pour montrer l’évolution du bassin arrière-arc océanique de Nain-Baft (les pointillés représentent la limite lithosphère [L]-asthénosphère [A]). A. Pendant le Trias supérieur et le Crétacé inférieur, la présence de l’arc magmatique mésozoïque (représenté par ... Lire la suite

Northward migration of the arc, from Upper Trias, south of the Sanandaj-Sirjan Zone, to Upper Eocene, Plio-Quaternary time crosscutting the Nain-Baft suture or even to the north is the common rule along the southern part of the Iranian block [7,38] (Fig. 5). The Cretaceous back-arc basins of the Nain-Baft belt are situated to the North of the Upper Triassic-Lower Jurassic marginal basins of the Esfandagheh region. This suggests that the subduction induces alternating extension to give birth to the back-arc basins and compression inducing the northward migration of the arc. This mechanism can be generated either by changes in the dip of the subducting slab or change in its velocity and/or obliquity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported financially by the French CNRS (contribution of the UMR 7516 “Institut de physique du Globe”, Strasbourg, France), the Cultural Service of the French Embassy at Tehran and Iranian Ministry of Sciences, Research and Technology. We are deeply indebted to Dr. Blanchy and Dr. Duhamel who greatly facilitate this research. R. Boutin and R. Thuizat from the University of Strasbourg have performed respectively chemical analysis and age determination. Finally, we are very grateful to Professor Hervé Bellon for his constructive review of the manuscript and to another anonymous reviewer.