1 Introduction

The Dead Sea (DS) is the terminal lake of the Jordan River system, located 420 m below sea level (B.S.L.) in an extremely arid environment with an annual precipitation of 50–100 mm. The typical geological section is composed of alluvial fan sediments to a depth of 20–30 m, a layer of marl 5 m thick, and a salt layer of 10–20 m thickness. The salt layer is underlain by clay and gravel. At most sites, the top of the salt layer is at a depth of 25–50 m from the surface and 5 to 20 m below the water table. Thus salt and clay sediments divide the sand and gravel formation into several subaquifers [17]. The hydraulic head in the deeper confined aquifer is higher than the hydraulic head in the shallow phreatic aquifer. Fresh water enters the aquifer from the Judean aquifer at the west and flows eastward to the DS while mixing with brine. The ground water is characterized by very high salinity, similar to DS water, with a concentration of 100–225 g/l chloride.

Since 1960, large amounts of fresh water have been diverted from Lake Kinneret and the Jordan River, which has contributed to an increasing drop in DS level, estimated in 2004 at approximately 0.8 m/yr. The drop of the DS level is accompanied by a corresponding lowering of the groundwater level and intrusion of fresh water into the coastal aquifer [17]. In Israel, the process of sinkhole development began in 1980 in the southern part of the Dead Sea coast (Mor, Newe Zohar), and has slowly spread to the north.1 In the literature, the development of sinkholes is explained by the salt dissolution model [3,19]. According to this model, the drop of the DS level shifts downward the fresh-saline water interface thus creating a contact between the salt layer and the fresh water. When the DS level was high, the salt layer was protected by saturated saline water. Then the salt was dissolved and caves grew at a depth of 20–50 m, which later caused soil collapse and sinkhole development.

Consequently, detailed knowledge of the fresh-saline water interface is important for a correct management of the sinkhole problem in the region. In this study, we used surface geophysical methods to monitor the fresh-saline water interface.

2 Method

2.1 The Transient Electromagnetic method (TEM)

TEM is sensitive to subsurface conductivity, which is closely linked to groundwater salinity. This method is routinely used in Israel for monitoring groundwater salinity and locating the fresh-saline water interface in coastal areas [4,6,18]. Based on electrical resistivity measurements, the following classification is generally used for the DS area: (1) very saline water (brine), with a resistivity of ρ < 1 Ωm; (2) diluted brine, with a resistivity of 1 Ωm < ρ < 3 Ωm; and (3) less saline (brackish) water, with a resistivity of ρx > 3 Ωm.

Commonly, ground exploration using TEM involves placing a square loop in the vicinity of the area to be examined and performing soundings or profiling [14]. We used a coincident-loop configuration, with the same loop acting both as transmitter (Tx) and receiver (Rx) [2]. We presumed the presence of dimensional variations of water salinity and of the geometry of the interfaces in the area. The TEM FAST 48HPC system meets the requirements of the proposed exploration. The high productivity of the TEM FAST equipment in a light, portable unit that uses a single Rx/Tx loop is an important advantage. The coincident-loop configuration accelerates the fieldwork. While this configuration is much more sensitive to Induced Polarization (IP) and magnetic viscosity or the Super Paramagnetic Effect (SPM) effect than the central loop configuration, conventionally used in Israel [4], these effects must therefore be evaluated routinely with this type of equipment. Under DS conditions, however, where young sediments are characterized by low magnetic susceptibility of 5–8 × 10−5 SI [15], the SPM effect does not influence the TEM measurements.

TEM data were interpreted with commercially available 1D inversion software. TEM-Researcher software was used for modelling and inversion of the large sets of TDEM soundings and for the generation of pseudo- and inverse-resistivity maps and sections [2]. For more complete estimations of the inversion results with equivalent models, IX1D software by Interpex Ltd was used.

It is well known that the TDEM method is sensitive to bulk resistivity (electrical conductivity) medium, especially in the low resistivity range. Bulk resistivity depends on the salinity of groundwater in porous media and on porosity. It is described by Archie's law [1] for fully saturated rocks:

| (1) |

| (2) |

It follows from Eq. (2) that the resistivity depends on both the porosity of the medium (which depends upon the lithology) and the resistivity of the water filling the pores, which creates the interpretation ambiguity. Consequently, it is impossible to use only TEM measurements to determine both the water resistivity (ρw) and the porosity (ϕ). Usually, parameters ρw and ϕ are not known, and one of them is assumed to be constant throughout the investigated area. When this assumption is not true, some additional knowledge about the subsurface is required to correct the interpretation of TEM data.

2.2 The Magnetic Resonance Sounding method (MRS)

MRS is a selective method, particularly sensitive to groundwater [10,12]. Two main parameters are derived from MRS measurements: (a) the MRS water content (w) and (b) the T1 relaxation time. Assuming a horizontal stratification, inversion of sounding data estimates the water content w(z) and the T1(z) relaxation time as a function of depth [9]. MRS results are averaged over a large area defined by the loop size. Both w(z) and T1(z) are closely related to the hydrodynamic properties of water saturated rocks [8]. The hydraulic conductivity can be estimated as

| (3) |

All MRS measurements were carried out with the NUMISPlus MRS system developed by IRIS Instruments (France).

3 Combined interpretation of TEM and MRS results

It is known that total porosity decreases monotonically from fine to coarse fractions [16]. For example, it could be clay or silt and gravel or cobbles respectively. Bulk electrical conductivity (resistivity) depends on total porosity and clay content among other factors. A simple estimation reveals that from gravel to clay the porosity changes more than twofold, and according to Eq. (1), the resistivity can change fivefold even if the resistivity of the groundwater does not change. It is also known that increasing clay content will cause a resistivity decrease even higher than that predicted by the Archie's law.

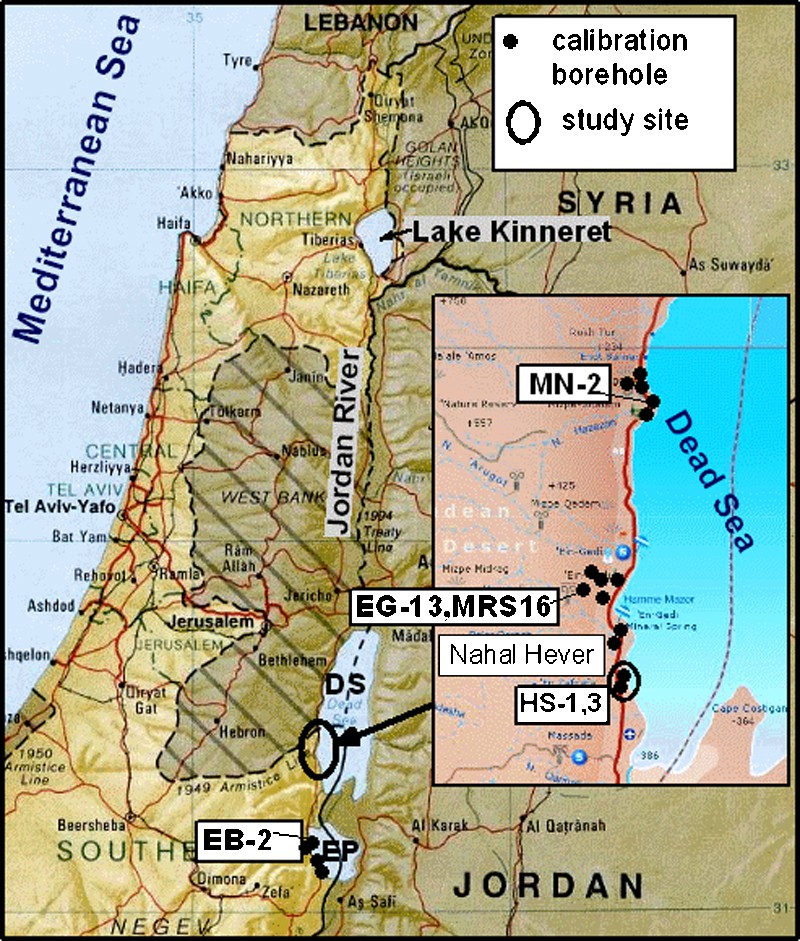

The drastic resistivity change was experimentally confirmed in conditions typical of the DS. TEM measurements were performed near two boreholes located in the central (Mineral-2) and southern (Ein Boqeq-2, or EB-2) parts of the DS coast (Fig. 1).

Location of investigated area. Black circles designate the calibration boreholes.

Situation de la zone d’étude. Les cercles noirs désignent les forages d’étalonnage.

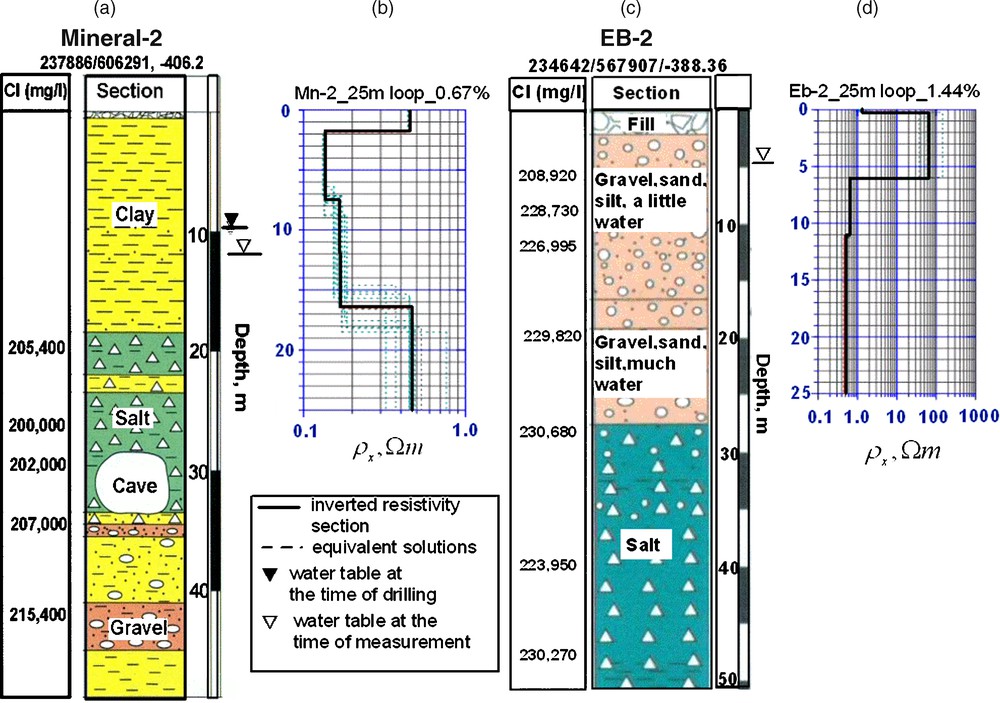

Measurements in boreholes were carried out by the GSI.2 Results are shown in Fig. 2. Chloride concentration in the groundwater (mg/l) is represented in the left-hand columns of the geological sections. The TEM interpretation of soundings close to these boreholes shows the inverted resistivity vs. depth graphs (thick line) and equivalent solutions (thin dashed line). The temperature of the water is 28.8 ± 0.2 °C at Mineral-2 in a depth range of 22–28 m and 29.3 ± 2 °C at the EB-2 borehole in a depth range of 6–28 m. The uppermost part of the Mineral-2 section (a) is composed of clay saturated with DS brine; the uppermost part of the EB-2 section (c) is composed of sandy soil, also saturated with DS brine.

TEM results near boreholes: geological (a, c) and inverted resistivity (b, d) sections of two boreholes: Mineral-2 and Ein Boqeq-2 (EB-2).

Résultats des sondages TDEM proches des forages : coupes géologiques (a, c) et résistivité inversée (b, d) de deux forages : Mineral-2 et Ein Boqeq-2 (EB-2).

Results show that for a constant water concentration bulk resistivity strongly depends on the rock. Clay material saturated with very saline water is characterized by a resistivity of less than 0.2 Ωm, but sand and permeable salt reveal a resistivity of about 0.5 Ωm or more.

MRS measured relaxation time T1(z) is sensitive to the grain size of water-saturated rock. Consequently, when the grain size of sand and clay content varies it also causes T1(z) changes. Typically, decrease of the grain size (increasing porosity) and increase in the clay content both cause a diminishing of T1. The electrical conductivity of rocks increases nonlinearly both with increasing porosity and increasing clay content. Thus, an increase of the electrical conductivity is accompanied by diminishing T1(z). Obviously, for each particular site, we do not know from surface measurements which dominating factor causes the variations in the electrical conductivity of the subsurface, the porosity or the clay content.The quantitative relationship between MRS relaxation time and the lithology of saturated rock is not available, and the literature contains only qualitative descriptions (Table 1). But to interpret TEM measurement, even qualitative information about the subsurface can be useful for verifying whether or not the rock material is changing. MRS measurements near boreholes reveal that in the Dead Sea area MRS results are generally in good agreement with those reported earlier [11] (Table 1). For example, MRS relaxation time T1 = (50 ÷ 70) ms was measured in clayey lithology in Nahal Hever south, whereas T1 = 430 ms was obtained in a sand-and-gravel aquifer at the Ein Gedi site.

Temps de relaxation du signal RMP mesurés dans des différentes roches [18].

| Rock type | T1 (ms) | Comments |

| Reef limestone (Cyprus) | 220 | Unsaturated zone |

| Clay and fine sand (France) | 310 | Aquifer |

| Medium sand (France) | 420 | Aquifer |

| Fractured limestone (Cyprus) | 430 | Aquifer |

| Gravel and coarse sand | 600 | Aquifer |

| Highly fractured limestone (France) | 800 | Aquifer |

| Karst limestone (Cyprus) | 1000 | Aquifer |

4 Field results

The area investigated with TEM and MRS (Nahal Hever south) is located in the central part of the northern DS Basin in Israel (Fig. 1). The Nahal Hever test site was selected by GII as a representative area of the Dead Sea shore. In addition, convenient access, smooth surface topography (practically plain), and a low level of electromagnetic noise render this area suitable for performing a complicated study using MRS and TEM techniques. Significant lithological variations within this area were neither known nor expected. Since 1992, many sinkholes have appeared. Salt dissolution by fresh water was presumed by geologists. However, no fresh water was found in the two boreholes drilled in the vicinity of sinkholes. The major goal of the present study was the investigation of the water salinity variations in the area.

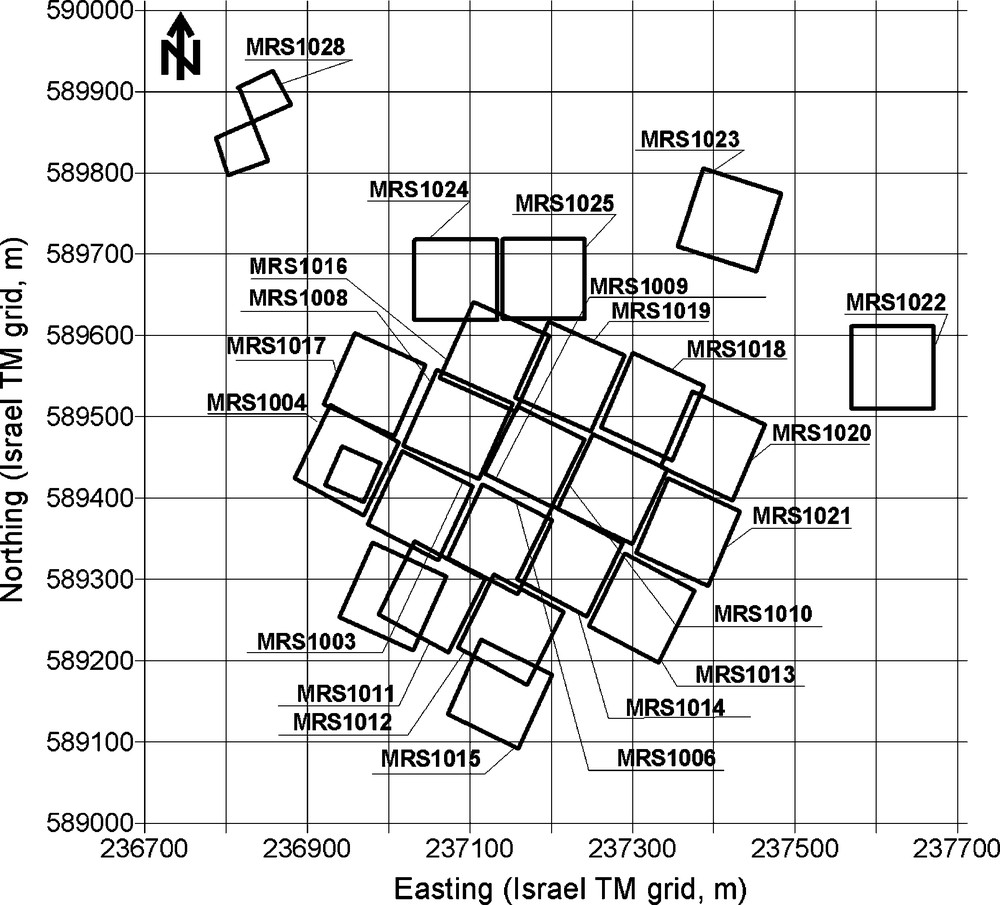

Twenty-four soundings were performed in 2007. The location of MRS stations is shown in Fig. 3. At each location, the MRS was accompanied by a TEM sounding.

Location of MRS stations in Nahal Hever south.

Position des sondages RMP au sud de Nahal Hever.

MRS measurements were carried out with a square loop of 100 × 100 m2. Under Nahal Hever conditions, characterized by a very high subsurface conductivity, the depth of investigation with this loop was estimated at 45–50 m. For TEM measurements, a coincident 25 × 25 m2 loop was used.

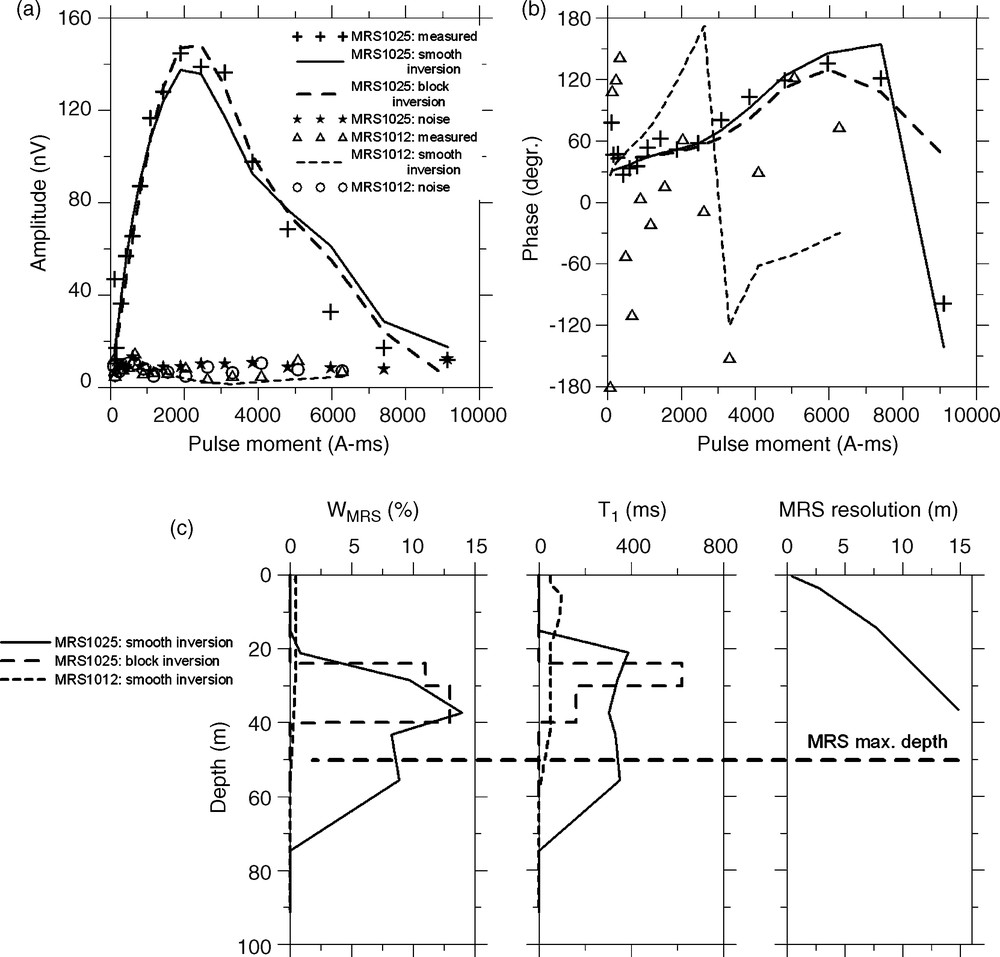

An example of MRS results is presented in Fig. 4. For demonstration purposes, we selected two soundings typical of the northern and southern parts of the investigated area.

Example of MRS results typical for the northern (MRS1025) and southern (MRS1012) parts of Nahal Hever: (a): amplitude of MRS signal versus pulse moment; (b): phase of MRS signal versus pulse moment; (c): inversion results: w(z) and T1(z).

Exemples de résultats RMP typiques pour la partie nord (MRS1025) et la partie sud (MRS1012) de Nahal Hever : (a) : amplitude du signal RMP en fonction du moment d’impulsion ; (b) : phase du signal RMP en fonction du moment d’impulsion ; (c) : résultats d’inversion : w(z) et T1(z).

We observe a great difference between these two stations. The MRS signal recorded at station 1012 is very close to the noise level that corresponds to a very small amount of mobile water in the subsurface. On the contrary, a very distinct signal was observed at station 1025. Inversion results reveal a water content of about 1 and 12% respectively. A large difference was also observed in the relaxation times. The maximum depth of investigation was estimated at approximately 50 m and the resolution was estimated by SVD analysis [13]. One can see that the resolution at a depth of 20 m is about ± 10 m. Obviously, such a resolution does not allow us to resolve a 10 m thick salt layer by smooth inversion. However, if the location of the salt layer is known from the borehole then we can assume that the water content and relaxation time in salt is different from that in surrounding rocks and thus investigate MRS parameters in two layers. For example, whether w and especially T1 are smaller (solid salt rock) or larger (karst) in comparison with the surrounding sand formation. Example of a two-block-inversion is presented in Fig. 4. For station 1025, the relaxation time was estimated at 480 < T1 < 830 ms, which suggests that salt may be karstified.

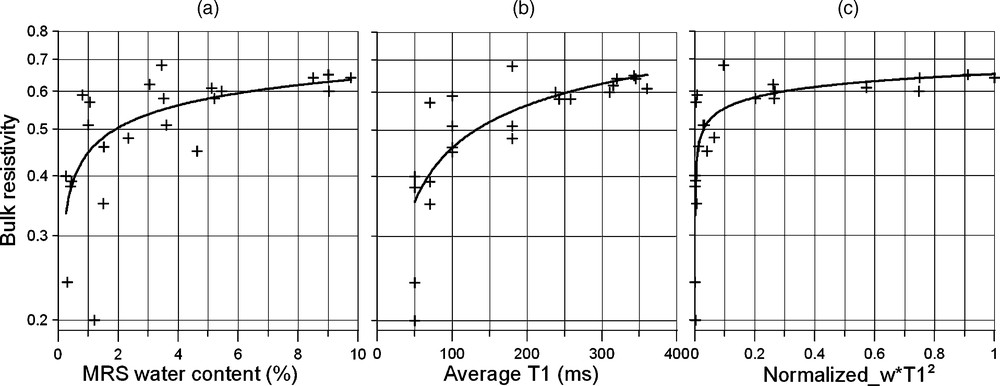

Experimental correlation between TEM and MRS results in Nahal Hever is summarized in Fig. 5. For this demonstration, we used the smooth inversion results, as they were considered more objective.

Experimental correlations between TEM and MRS results: (a): bulk resistivity versus MRS water content; (b): bulk resistivity versus MRS relaxation time T1; (c): bulk resistivity versus normalized MRS estimator of the hydraulic conductivity.

Corrélations expérimentales entre des résultats TDEM et RMP : (a) : résistivité en fonction de la teneur en eau RMP ; (b) : résistivité en fonction du temps de relaxation du signal RMP T1 ; (c) : résistivité en fonction de la valeur normalisée de l’estimation RMP de conductivité hydraulique.

We observe that generally the resistivity increases for larger water content and relaxation time. However, for larger values of MRS parameters, the resistivity is only slightly increased, whereas for T1 < 150 ms and wMRS < 2%, the resistivity changes threefold for practically unchanging MRS parameters. Indeed, T1 increasing from 150 to 350 ms points to coarser material. But as the groundwater is extremely saline, the bulk resistivity increases slowly. When T1 < 150 ms, MRS only indicates that some compact rock is detected. Under Nahal Hever geological conditions, such a compact rock may be either clay or solid salt rock. But electrical resistivity of clay ranges between 0.2 and 0.4 Ωm and that of solid salt between 0.8 and 1.5 Ωm. Use of the MRS estimator of hydraulic conductivity given by equation (3) diminishes dispersion in the correlation. As we have no calibration boreholes in Nahal Hever, we can use only estimated relative hydraulic conductivity.

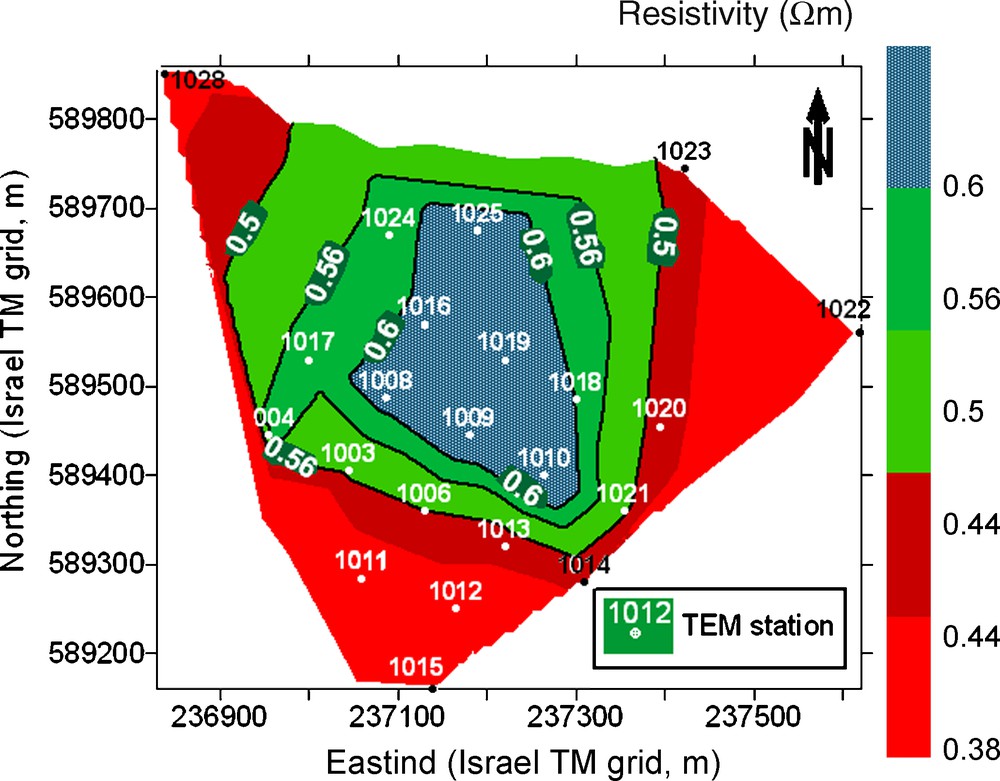

The map of bulk resistivity in the Nahal Hever was created using the measurements and 1D inversion of TEM soundings (Fig. 6). This map corresponds to the average electrical resistivity of the subsurface between 20 and 40 m. If we interpret these data with the usual assumption that the rock material is homogeneous throughout the area, implying a constant lithology, the TEM results would produce a very strong indication that the salinity of groundwater diminishes from the South to the North of the area.

Map of a bulk resistivity of DS aquifer (ρx) in Nahal Hever south.

Carte de résistivité dans l’aquifère de la Mer Morte (ρx) au sud de Nahal Hever.

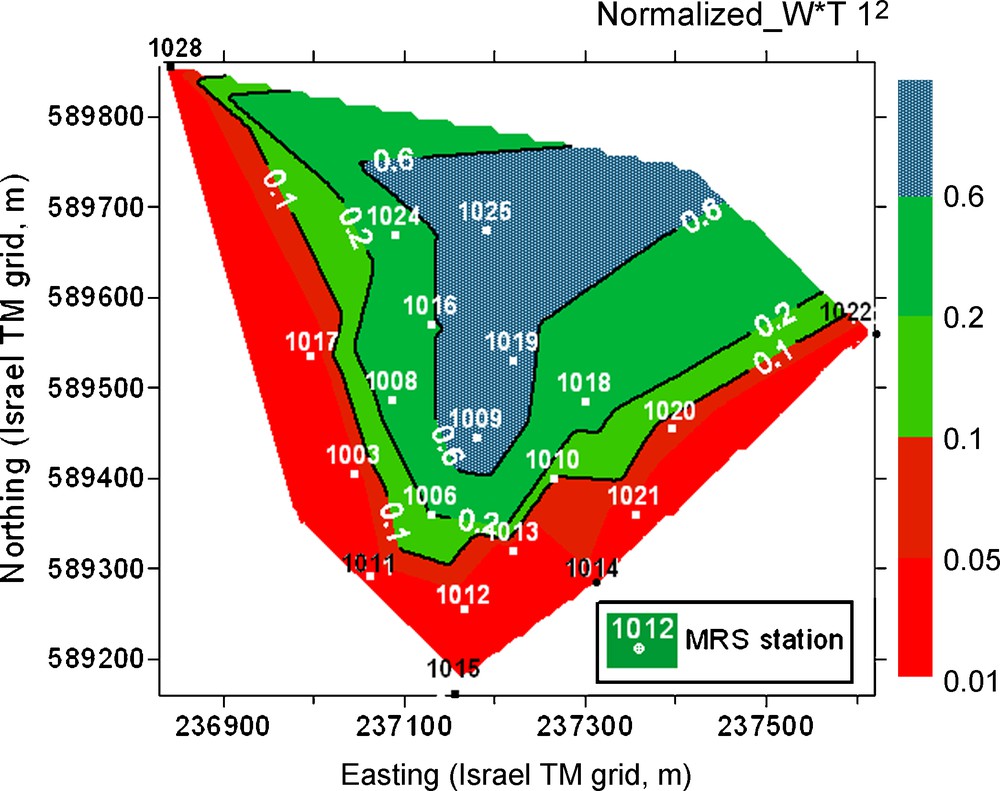

The often-used assumption when interpreting TEM data that the lithology is constant throughout the area was verified in Nahal Hever with the MRS method. However, MRS results reveal that the subsurface is very heterogeneous. The map of normalized MRS estimation of the hydraulic conductivity is shown in Fig. 7. Large differences are observed throughout the area. The relaxation time changes from 50–70 ms in the southern part of the investigated area to 350 ms in the centre (Fig. 5). Considering the relationship between the MRS relaxation time and the rock material (Table 1) and the varying hydraulic conductivity, we conclude that the total lithology changes from the southern margin to the north. Therefore, changes in lithology are sufficient to explain the variations in resistivity observed with TEM (Fig. 6). In this way, the combined use of TEM and MRS enables us to conclude that in Nahal Hever the electrical conductivity of the groundwater, closely related to the salinity, does not necessarily change significantly between the southern and northern parts of Nahal Hever.

Map of normalized MRS hydraulic conductivity in Nahal Hever south.

Carte des valeurs normalisées de l’estimation RMP de conductivité hydraulique au sud de Nahal Hever.

5 Discussion

Results of both TEM and MRS methods reveal a heterogeneous lithological structure of the NHS area. The experimental relationship between ρx and MRS results is presented in Fig. 5 for all the collected data. Figure 5 shows a relatively large dispersion of the data. This dispersion can be explained by inaccuracies of 1D TEM and MRS results in the highly heterogeneous subsurface but also by complicated relationships between the measured surface physical parameters of the rock (bulk resistivity, MRS amplitude and MRS relaxation time). Indeed, the subsurface is composed of clay, sand, gravel, and salt that is partly karstified. Below approximately 20 m, the rocks are saturated with very saline water. Nevertheless, joint use of TEM and MRS improves the accuracy of interpretation. For the interpretation, we used MRS derived water content and relaxation time and bulk resistivity measured with TEM. We also used calibration of TEM near 18 boreholes (Table 2). This allowed us to identify in Nahal Hever three different types of rock:

- 1) the northern part of the area is characterized by high values of MRS relaxation time and MRS water content (and consequently high MRS hydraulic conductivity) and a resistivity of the aquifer of 0.6 <ρx < 1.0 Ωm. This result suggests that the area is composed of permeable rock (sand and probably karstic salt formation) saturated with very saline water (DS brine);

- 2) in the southern part of the area, the MRS method reveals relaxation times of less than 100 ms and low water content, which corresponds to low permeable material (clay, silt, compact salt). An electrical resistivity of less than 0.4 Ωm is typical for clayey material saturated with DS brine. It is also possible that a solid salt formation is enveloped by clay;

- 3) some TEM measurements reveal relatively high resistivity between 0.4 and 0.6 Ωm (and even 1.0 Ωm) but an MRS estimation of the hydraulic conductivity suggests a low permeability formation (for example soundings 1010, 1018). We interpret this formation as solid salt surrounded by relatively low clay content materials.

Résistivité mesurée par la TDEM proche des forages d’étalonnage.

| Borehole | Lithology | Depth of water sampling (m) | Chloride concentration measured in borehole (g/l) | Bulk resistivity measured with TEM (ρx, Ωm) | Comments, salt depth range (m) |

| Dr-3a | Grvl + sndb | 78–85 | 153.3–201.4c | 0.5 | Sinkhole site |

| Dr-4 | Grvl | 60–65 | 218.7–219.2 | 0.5 | Sinkhole site |

| Mn-1 | Cly | 20–35 | 121–123.3 | 0.3 | |

| Mn-2 | Cly | 29–42 | 202–215.4 | 0.2 | Sinkhole site |

| Mn-4 | Cly | 37–56 | 207.9–221.4 | 0.2 | |

| EB-2 | Snd | 40–80 | 222.1–233.7 | 0.5 | |

| HS-2 | Grvl + cly | 45–70 | 200–220 | 0.3 | Sinkhole site |

| NZ-3 | Cly + snd | 15–35 | 188–224 | 0.3 | |

| EG-18 | Snd + cly | 32–60 | 112–150 | 0.4 | |

| EG-17 | Grvl | 29–40 | 176–219 | 0.5 | |

| EG-11 | Snd | 16–20 | 151.7–197.9 | 0.4 | |

| EG-19 | Grvl + snd | 42 | 147 | 0.6 | 1st (upper) aquifer |

| EG-19 | Grvl + snd | 50 | 16.94 | 1.6 | 2nd (lower) aquifer |

a Site names: Dr: Deragot; Mn: Mineral Beach (Shalem-2); EB: Ein Boqeq; HS: Nahal Hever south; EG: Ein Gedi–Arugot.

b Lithology: Slt: silt; Grvl: gravel; Snd: sand; Cly: clay.

c Chloride saturation is accepted to be 224 g/l in the northern DS basin and 259 g/l in the evaporation ponds area [1].

6 Conclusions

Combined use of TEM and MRS methods makes it possible to investigate variations in groundwater salinity and in the lithology of water-saturated rocks. TEM is known as an efficient tool to electrically investigate conductive media such as saline water, but it is sensitive to both the salinity of the groundwater and the lithology of the rocks. MRS, however, is more sensitive to the amount of groundwater and the lithological variations in the subsurface than to the electrical conductivity. We show that under Nahal Hever conditions, MRS contributes to resolving the fundamental uncertainty in the TEM interpretation, which is caused by the equivalence between groundwater resistivity and the lithology.

In the Nahal Hever south, we observed with TEM an increase of resistivity from the South to the North of the area, caused primarily by changes in the rock material. These lithological variations observed with MRS allow us to explain the observed increase in resistivity assuming unchanging salinity of the groundwater. Thus, our results suggest that groundwater salinity in Nahal Hever does not change significantly around the area. As long as ρx is less than 1.0 Ωm, it is characteristic of DS brine saturated alluvium.

By combining TEM and MRS, we were able to show that the DS aquifer in the zone of sinkhole formations is characterized by a bulk resistivity of ρx > 0.4 Ωm, whereas the zones of silt and clay detected with MRS in the South of the area are characterized by a bulk resistivity of ρx < 0.4 Ωm. These observations are confirmed by calibration of the TEM method, performed near 18 boreholes (Figs. 2 and 3, Table 2).

Acknowledgements

The present study was sponsored by the NATO Security Through Science Program (Project SfP No 981128). We are grateful to the Israel Ministry of Infrastructure for supporting the study. Special thanks are due to Dr. U. Frieslander and to the GII staff for contributing to the administration of the project. We wish to thank persons in charge of studying the sinkhole problem in the Geological Survey of Israel, Drs. Y. Yechieli and M. Abelson, for providing geologic information about the investigated areas. We thank the anonymous reviewer who has assisted us in significant improvement of the manuscript.

1 Geological Survey of Israel, Krovi et al., Report No. TR-GSI/20/04 (in Hebrew).

2 Geological Survey of Israel, Yechieli et al., Report Nos. GSI/21/04 and GSI/06/2005 (in Hebrew).