1 Introduction

Soils deficient in zinc (Zn) and iron (Fe) constrain rice (Oryza sativa) production in large parts of the world (Dobermann and Fairhurst, 2000) and deficiencies of Zn and Fe in human populations with rice-based diets cause major health problems for millions of people (Graham, 2007). Identifying nutrient efficient rice lines, applying appropriate breeding techniques, and understanding the underlying mechanisms of Zn and Fe efficiency, are important for tackling this large societal challenge (Wissuwa et al., 2008).

Recent work demonstrated significant isotope fractionation during uptake and translocation of trace metals including Fe, Cu and Zn from soils to plants in a wide variety of plant species and this suggests that natural stable isotope compositions provide a powerful technique to study the chemical and biological processes that control micronutrient movement from soils into plants (Alvarez-Fernandez et al., 2014). Isotopic fractionations differ between plant species and between genotypes of the same species, as well as with soil and nutritional conditions (Arnold et al., 2010a; Aucour et al., 2011; Deng et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2012; Weiss et al., 2005; Weinstein et al., 2011).

Work on the isotopic fractionation during Zn uptake in hydroponic cultures showed that plant shoots are enriched with 64Zn relative to 66Zn in comparison to the source, consistent with an unidirectional process during transport of free Zn2+ across cell membranes (Aucour et al., 2011; Deng et al., 2014; Weiss et al., 2005). Plants grown in natural soils, however, show negligible or slight heavy isotope enrichment in the shoots (Arnold et al., 2010a; Tang et al., 2012; Viers et al., 2007). Recent work suggests that uptake of a Zn(II)-phytosiderophore (PS–Zn) complex could account for an observed heavy isotopic fractionation in Zn uptake by rice (Arnold et al., 2010a). Likewise Smolders and co-workers account heavy isotopic fractionation during Zn uptake by tomato plants in resin-buffered hydroponics by the uptake of a PS–Zn complex (Smolders et al., 2013). Investigations of Zn complexation by organic molecules using experiments in the laboratory (Jouvin et al., 2009) and ab initio calculations (Fujii and Albarède, 2012) support this model. Few studies determined the stable isotope fractionation of Zn during translocation in higher plants but enrichment with light isotopes in leaves with increasing distance from the root (Caldelas et al., 2011; Moynier et al., 2009; von Blankenburg et al., 2009) and during the translocation from root to shoot (Caldelas et al., 2011; Jouvin et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2012) have been reported.

To date, Fe isotope fractionation has not been studied in rice but a significant body of work exists for graminacae (Guelke and von Blankenburg, 2007; Kiczka et al., 2010b; von Blankenburg et al., 2009; Guelke et al., 2010). The observed range of isotope fractionation is around 2.25‰ per atomic mass unit (pamu). Initial pot studies found an enrichment with light Fe during plant uptake in strategy-I plants as opposed to an enrichment with heavy isotopes in strategy-II ones (Guelke and von Blankenburg, 2007). These observation are in line with known plant uptake and isotope fractionation mechanism, whereby a reduction reaction and subsequent uptake of ferrous iron is responsible for the enrichment with light Fe isotopes in strategy-I plants, and the complexation of Fe3+ by organic ligands and the subsequent uptake of the PS–Fe complex is responsible for the enrichment with heavy isotopes in strategy-II plants. Subsequent work found significant variation in isotopic fractionation among different graminaceous species, showing positive and negative isotope signatures suggesting that the controls are far more complex (Guelke-Stelling and von Blanckenburg, 2012; Kiczka et al., 2010b). One proposed explanation is that strategy-II plants possess transporters for ferrous Fe and thus can take up Fe2+ directly (Cheng et al., 2007; Kim and Guerinot, 2007). Kiczka et al., 2010b suggested two consecutive stages during Fe uptake to explain light Fe enrichment in graminacae, and in particular processes preceding active transport such as mineral dissolution which favours for trace metals the removal of light isotopes (Chapman et al., 2009; Kiczka et al., 2010a, 2011; Weiss et al., 2014; Wiederhold et al., 2006, 2007a, 2007b) and selective Fe uptake at the plasma membrane level. These more recent observations emphasize the possible effect of mixing of different chemical forms on the Fe and other trace metal isotope signature found in stems, grains and leaves during the transport in phloem and xylem (Guelke-Stelling and von Blanckenburg, 2012; Moynier et al., 2013). Although Fe speciation during root uptake is a major contributor to the final isotopic signature, possible mechanisms that influence isotope distribution within plants include successive oxidation and reduction steps during translocation, ligand exchange reactions, remobilisation from older plant tissues and mixing effects of short- (phloem) and long-distance (xylem) transport (Alvarez-Fernandez et al., 2014; Yoneyama et al., 2010).

The aim of the present study was to investigate the controls of stable isotope fractionation of Zn and Fe in rice (Oryza sativa) grown under aerobic and anaerobic soil conditions. We conducted experiments in a nutrient-sufficient soil with a widely grown rice genotype. We analysed soil, leachable fractions, shoots and grains, and we discuss the observed fractionation patterns in light of the possible mechanisms outlined above.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant growth experiments

Rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. Oochikara) was grown in pots in a greenhouse at Rothamsted Research under anaerobic (flooded) and aerobic conditions as described elsewhere (Xu et al., 2008). The soil was taken from the plough layer (0–20 cm depth) of an arable field at Rothamsted. It is a moderately well-drained Aquic Paleudalf (USDA classification) or Luvisol (FAO classification) with silty clay loam texture (26% clay, 53% silt, 21% sand), 2% organic C, 0.2% total N, 5.93 g kg−1 amorphous Fe oxides (by ammonium oxalate extraction) and pH 6.4. The soil was air-dried, sieved to < 8 mm and homogenized. Two watering treatments (aerobic and flooded) with four pots per treatment were randomly arranged on a bench inside a greenhouse (day/night temperatures 28/25 °C, light period 16 h per day with natural sunlight supplemented with sodium vapour lamps to maintain light intensity of > 350 μmol m−2s−1). Five pre-germinated rice seeds were planted in each pot. To grow rice under aerobic conditions, plastic pots with holes at the bottom were placed on saucers and filled with 1 kg of soil, while for anaerobic conditions pots without holes were used. Fertilisers (120 mg N·kg−1 soil as NH4NO3/(NH4)2SO4, 30 mg P·kg−1 and 75.5 mg K·kg−1 soil as K2HPO4) were added to the soil and mixed thoroughly. Deionised water was added to full saturation with 2 cm of standing water for anaerobic rice, and to 70% of the soil's water holding capacity for aerobic rice. The two watering regimes were maintained throughout the experiment by daily additions of deionised water. Two further doses of 50 mg of N (NH4NO3) were added to each pot at 33 and 70 days after planting. The plants were harvested at grain maturity (117 days after planting). Stems were cut at 2 cm above soil surface, rinsed with deionised water, and dried at 60 °C for 48 h. The samples were separated into straw and grain (including husk), ground, pooled in one sample per pot and then aliquots were processed as described below. Root material was not collected for analysis because a large fraction of the roots had died and degenerated when the plants reached maturity. Only the above ground shoot materials were used.

2.2 Reagents, sample preparation, ion exchange chromatography and mass spectrometry

Sample preparation was carried out in Class-10 laminar flow benches within class 1000 clean room facilities. Mineral acids except for HF were purified from Analar grade by sub boiling distillation in quartz stills. Distilled HF (∼28 M Ultrapure grade) and H2O2 (∼30% v/v Aristar grade) were purchased from VWR. All acid dilutions used > 18.2 MΩ cm−1 grade H2O from a Millipore purification system.

Oven-dried plant samples were ground using a porcelain pestle and mortar with liquid nitrogen and passed through a 0.5 mm2 sieve. Plant samples were digested using a CEM Microwave Accelerated Reaction System (MARS) with 100-mL XP-1500 Teflon vessels. 5 mL of 15 M HNO3, 3 mL 30% H2O2, and 0.6 mL 28 M HF were added to approximately 0.35 g of material. The acid-solid mixture was ramped to 210 °C and 250 psi and held for 90 min. Soil samples (50 mg) were digested using the same protocol. Soil leaches were used to estimate the composition of the Zn pool available to the plants. 30 mL 0.1 M HCl was added to 0.3 g of air-dried soil, and the resulting suspension was stirred continuously for 48 h at 25 °C. The suspension was centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected.

After digestion, samples were evaporated to dryness and the residue was dissolved in ∼1 mL 7 M HCl with 0.05 mL 30% H2O2 added to prevent reduction of ferric Fe. The solutions were dried again and re-dissolved in 2.5 mL 7 M HCl containing 0.001% H2O2 by volume. These solutions were split into three aliquots for Zn and Fe concentration measurements, for isotopic analysis, and for archive. The 0.5-mL aliquots for concentration measurement were diluted to 3.5 mL and made up to 1 M HCl and the measured using a Varian quadrupole ICPMS.

The separation of Zn and Fe from the matrix for subsequent isotope ratio measurements utilized Bio-Rad Poly-Prep columns filled with 2 mL of AG MP-1 100–200 mesh anion exchange resin. The resin was conditioned with 7 M HCl (10 mL) and successively washed with 0.1 M HNO3 (10 mL), H2O (10 mL), 0.1 M HNO3 (10 mL) and H2O (10 mL). The resin was re-conditioned with 7 M HCl-0.001% H2O2 (7 mL) and the samples loaded (1 mL solution in 7 M HCl-0.001% H2O2). The majority of matrix elements were eluted using 30 mL 7 M HCl-0.001% H2O2. This was followed by elution of Fe using 17 mL 2 M HCl and Zn using 12 mL 0.1 M HCl. The resin was then washed with 10 mL 0.5 M HNO3. The Zn and Fe fractions were dried down, dissolved in 0.2 mL 15 M HNO3, and dried to drive off residual HCl. Finally, 1 mL 0.1 M HNO3 was added and the samples refluxed for > 2 hours to ensure complete dissolution. The solutions were then ready to be analysed with the Nu Plasma MC-ICPMS.

The total procedural blank contributions, accounting for the dissolution and ion exchange procedures, were below 1% of the total Zn and Fe for the samples with the lowest concentrations. The effect of these blank contributions on the final isotopic results was therefore negligible compared to the measurement uncertainty and no blank correction was applied.

Zinc isotopes were analysed using the double spike method (Arnold et al., 2010b). An isotope spike enriched with 64Zn and 67Zn was added to the sample aliquot to achieve a total of 1000 ng of Zn and a spike: sample mass ratio of 1. Values are reported as δ66Zn relative to the widely used standard JMC−Lyon, i.e. δ66ZnJMC–Lyon = [(66Zn/64Zn)sample/(66Zn/64Zn)JMC–Lyon−1] × 103. The Fe isotope analyses were performed by standard-sample bracketing using the reference material IRMM-014 as the standard, as detailed elsewhere (Chapman et al., 2009). Values are reported as δ56Fe relative to the IRMM-14 standard, δ56FeIRMM-014 = [(56Fe/54Fe)sample/(56Fe/54Fe)IRMM-014−1] × 103.

Certified reference materials (rye grass BCR-281 and blend ore BCR-027) and single element industrial solutions (Johnson Matthey and Puratronic Alpha Aesar) were analysed to determine accuracy and precision of the isotope measurements (see Table 1 for details).

Dry mass, element concentrations and δ-values for Zn and Fe in shoots, grain and total material above ground of rice plants grown in aerobic and anaerobic soil. Plants were harvested 117 days after sowing. Also shown are the isotopic compositions of soil measured in the 0.1 M HCl extract and in bulk soil and in standard reference materials measured during this and previous studies (Caldelas et al., 2011; Chapman et al., 2006, 2009).

| Sample | Treatment | Comment | n | Zn/μg g−1 | δ66ZnJMC-Lyon/‰ | Fe/μg g−1 | δ56FeIRMM-014/‰ | Dry mass/g | |

| Rice | Anaerobic soil | Shoot | Measured | 4 | 32.6 ± 3.5 | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 95.2 ± 5.2 | −0.32 ± 0.16 | 11.9 ± 1.8 |

| Grain | Measured | 4 | 28.5 ± 0.5 | −0.18 ± 0.10 | 13.8 ± 0.6 | −0.39 ± 0.19 | 8.0 ± 1.6 | ||

| Total plant above ground | Calculated by mass balance | 4 | 0.32 ± 0.09 | −0.33 ± 0.16 | |||||

| Rice | Aerobic soil | Shoot | Measured | 4 | 75.5 ± 12.3 | 0.73 ± 0.12 | 96.1 ± 11.2 | −0.40 ± 0.07 | 12.5 ± 2.6 |

| Grain | Measured | 4 | 33.9 ± 3.6 | −0.00 ± 0.07 | 14.8 ± 1.3 | −0.23 ± 0.16 | 9.3 ± 2.4 | ||

| Total plant above ground | Calculated by mass balance | 4 | 0.51 ± 0.04 | −0.35 ± 0.07 | |||||

| Soil | Bulk | Measured | 2 | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | ||||

| 0.1 M HCl extract | Measured | 2 | 0.59 ± 0.02 | −0.27 ± 0.02 | |||||

| Reference material | Rye grass | This study | 3 | 0.40 ± 0.09 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | ||||

| Caldelas et al. (2011) | 0.50 ± 0.10 | ||||||||

| BCR 027 Blend Ore | This study | 4 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | ||||||

| Chapman et al. (2006) | 0.33 ± 0.07 | ||||||||

| Johnson Mattey | This study | 3 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | ||||||

| Chapman et al. (2009) | 0.49 ± 0.09 | ||||||||

| Puratronic Alpha Aesar | This study | 7 | 0.12 ± 0.13 | ||||||

| Chapman et al. (2009) | 0.10 ± 0.09 | ||||||||

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Zinc content and isotopic ratios of plants and soil

The average Zn concentration of the shoot tissue grown in aerobic soil is 75.5 ± 12.3 μg·g−1 (mean ± 1SD, n = 4) and approx. 2.3 higher than in rice grown in anaerobic soil (32.6 ± 3.5 μg·g−1, ± 1 SD, n = 4, Table 1). All measured concentrations are well above the threshold for deficiency, which is below 10 μg·g−1 (Dobermann and Fairhurst, 2000; Smolders et al., 2013), suggesting the plants were Zn sufficient in both soils. This conclusion is supported by the shoot and grain biomasses, which were not significantly different for the two water regimes, despite the difference in Zn concentration of the shoot (Table 1). The lower Zn uptake under anaerobic conditions is expected because of the reduced Zn solubility in submerged soils (Kirk, 2004). Under aerobic soil conditions, the shoots, i.e. stems and leaves, contain a greater proportion of the total plant Zn (75% versus 63% under anaerobic conditions). The total Zn concentration of the soil is 105 μg·g−1 whilst the 0.1 M HCl soil leach extracted 26 μg·g−1.

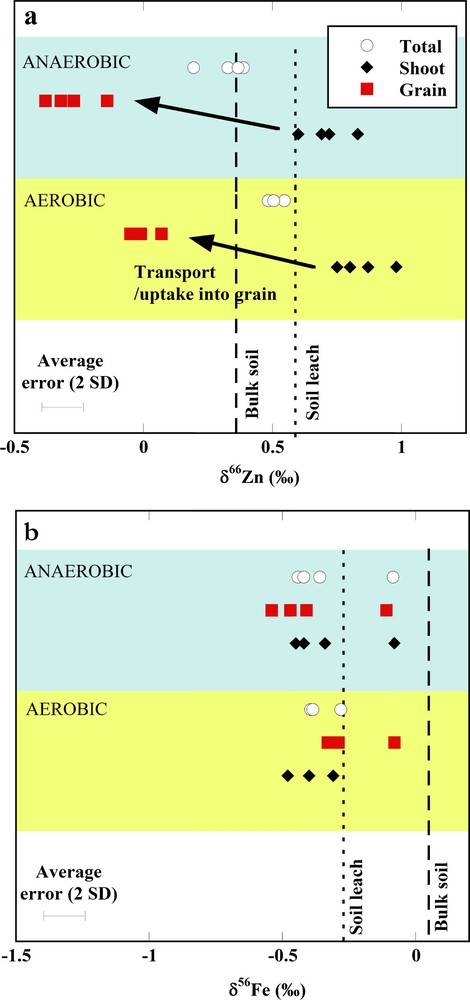

The Zn isotope compositions of the rice shoots, grains and the total above ground plant material are reported in Table 1. The total above ground plant value was calculated from the mass of the shoot and grain material and their corresponding Zn contents and isotope compositions. We find that the shoots of the rice plants grown under both soil regimes are isotopically significantly heavier than the bulk soil or leach (Fig. 1). The grains, in contrast, are isotopically light. The calculated Zn isotope composition of the total above ground plant material is closer to that of the shoot and soil leach and 0.19‰ heavier in the rice grown under aerobic conditions (Table 1). This difference is small but significant within the 95% confidence interval.

(Colour online.) Zinc (a) and Fe (b) isotope variations, expressed as δ66ZnJMC−Lyon and δ56FeIRMM-014, respectively, between bulk soil, soil leachate, shoot, grain and total above ground material.

We note a small difference in the isotope ratios in rice grown in aerobic or anaerobic soils. The shoots of rice grown in the aerobic soil yield a heavier isotope composition than the Zn in the labile soil pool. This is balanced by a bias towards light isotopes of Zn between shoot and grain, resulting in a small net negative bias between Zn in the total plant and the Zn in the soil leach. Under anaerobic soil conditions, the enrichment with heavy isotopes between soil leach and shoot transfer is smaller, and the net light bias between total above ground plant and soil solution is larger (Fig. 1).

Bulk and soil leach fractions show isotopic compositions (δ66ZnJMC−Lyon) of 0.36 ± 0.04 and 0.59 ± 0.02‰ (mean ± 1 SD, n = 2), respectively (Table 1). By mass balance, the Zn fraction remaining in the solid phase has a δ66ZnJMC−Lyon of ca. 0.28‰. This lies well within the range of igneous rocks and/or the inferred range of geological materials (Cloquet et al., 2008). It is possible that the 0.1 M HCl leachable fraction represents Zn from polluted atmospheric deposition, which can account for the heavier isotopic signature compared to the bulk soil (Weiss et al., 2014; Gioia et al., 2008).

3.2 Isotope fractionation processes of Zn during plant uptake and translocation

The isotopic fractionation between the different reservoirs is assessed employing the Δ66Zn notation calculated using the following equation (Weiss et al., 2013):

where Δ66ZnA−B is the isotopic fractionation between reservoirs A and B (i.e. soil leach, bulk soil, grain, shoot or above ground plant) and δ66ZnA,B are the isotopic signatures of the reservoir A and B. The results are given in Table 2.

Isotopic fractionations, expressed as Δ66Zn and Δ56Fe, between shoot, grain, total shoot and soil extract in 0.1 M HCl.

| Treatment | Δ66Znshoot–soil leach/‰ | Δ66Zngrain–shoot/‰ | Δ66Znplant above ground–soil leach/‰ | Δ56Feshoot–soil/‰ | Δ56Fegrain–shoot/‰ | Δ56Feplant above ground–soil leach/‰ |

| Anaerobic | 0.02 ± 0.09 | −0.79 ± 0.16 | −0.27 ± 0.09 | −0.37 ± 0.16 | −0.06 ± 0.10 | −0.38 ± 0.16 |

| Aerobic | 0.14 ± 0.12 | −0.67 ± 0.17 | −0.08 ± 0.04 | −0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.09 | −0.40 ± 0.07 |

The observed fractionations between the total above ground plant and the soil leach (−0.27‰ in anoxic soils and −0.08‰ in oxic soils) are well in line with that found in rice grown in hydroponic solution (Smolders et al., 2013; Weiss et al., 2005) and in submerged soils (Arnold et al., 2010a). The signatures in these previous studies were explained by the kinetically controlled uptake of free Zn2+ in the hydroponic studies and by the uptake of PS–Zn complexes in the submerged soils. Complexation to a phytosiderophore ligand in the soil solution prefers isotopically heavy Zn as shown by experimental and computational work (Fujii and Albarède, 2012; Fujii et al., 2014; Jouvin et al., 2009). Zinc has low solubility in aerobic and anaerobic soils and graminaceous plant roots, including rice, therefore secrete phytosiderophores to absorb the resulting Zn-phytosiderophore complexes (Reid et al., 1996; von Wiren et al., 1996; Widodo et al., 2010). We expect that phytosiderophore secretion is more pronounced in aerobic soil to solubilise Fe (III) and this indeed accounts for the higher Zn capture and the incorporation of heavier isotopes under aerobic soil conditions observed during this study (Fig. 1). We note that under Zn depletion in the soil solution, the isotopic composition of the total plant above the surface would trend towards that of the initial soil reservoir because the amount taken up approaches the total amount available in solution. The increased uptake of Zn observed under aerobic conditions and the isotopic composition of the total plant above the surface being closer to that of the soil leachate would be in line with this interpretation. However, mass balance calculations suggest that the rice extracted only a small fraction of the Zn that was available for extraction from the soil. The soil per pot contained approximately 26 mg Zn compared to 1.26 mg and 0.62 mg that were present in the plants under aerobic and anaerobic soil conditions, respectively (Table 1).

The grains show a significant enrichment with light Zn isotopes relative to the shoot material in rice grown under aerobic and anaerobic conditions alike (Table 2). The Zn budget of the shoot is accumulated over most of the growth season, whereas the grains largely accumulate their Zn during the grain-filling period of approximately 30 days. Previous work suggests that the rapid accumulation of Zn during the relatively short grain-filling period is controlled by the remobilisation of Zn from various parts of the plant and not by increased uptake from the soil medium (Nishiyama et al., 2012; Yoneyama et al., 2010). Our data indeed agrees with a stable isotope fractionation model for a unidirectional process such as translocation from shoot to grain (Fig. 2), the Rayleigh model is valid assuming that (i) the Zn is remobilized from the shoot during·grain-loading and the soil as additional source is excluded, (ii) the Zn pool of the shoot is not significantly replenished from the soil during this time period, and (iii) the Zn transport is not quantitative. The unidirectional model equation is given by:

Isotope fractionation model for unidirectional translocation of Zn from shoot to grain (expressed in fraction of above ground Zn in grain; see text for details regarding the model). The two data points represent the average Δ66Zn values between grains and shoot for rice grown under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Full arrows: data from this study, open arrows: data from literature including transfer from (1) seawater into algae (John et al., 2007), (2) seed to leaf in lentils and tuber to leaf in bamboo (Moynier et al., 2009), and (3) solution into tomato plant (Weiss et al., 2005). Only data from controlled systems are included, where sources and sinks can be unequivocally identified.

3.3 Iron content and isotopic ratios of the plants and soil

Plant Fe concentrations and the total amount of Fe do not differ significantly between the rice plants grown in the two contrasting soil environments (Table 1). In both treatments, the shoot Fe concentrations are well above the threshold range for deficiency, i.e., 50 to 100 μg·g−1 (Dobermann and Fairhurst, 2000). The Fe isotopic composition of the 0.1 M HCl leachate is about 0.3‰ lighter in δ56FeIRMM-014 than the bulk soil (Table 1). This is likely due to partial leach of selected mineral phases with an isotopically light signature and/or a kinetic mechanism whereby the lighter isotopes are readily removed (Chapman et al., 2009; Kiczka et al., 2010a; Wiederhold et al., 2006). The δ56FeIRMM-014 value of the soil leach is −0.27‰ (Table 1).

3.4 Isotope fractionation of Fe during uptake, translocation and grain-filling

The fractionations between plant tissues and the source are calculated for the Fe relative to the bulk soil as this enables us to compare our results with previous work (Guelke and von Blankenburg, 2007; Guelke-Stelling and von Blanckenburg, 2012). We find an enrichment with isotopically light Fe between bulk soil and shoot of up to 0.5‰ in aerobic and anaerobic soils alike (Table 2). The largest difference in Δ56Fe value is between shoot and bulk soil of plants grown on aerobic soils (0.45‰). The Fe taken up into the shoots has a significant lighter isotopic composition compared to the bulk soil but only insignificantly lighter relative to the soil leach (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

A notable finding is the similarity in the Fe isotopic composition between rice grown in aerobic and anaerobic soils, and the small fractionation between reservoirs. This suggests that the different physical-chemical conditions in the soils, i.e. redox potential, oxygen fugacity, solubility, do not affect the isotope signature in the plant, despite of the different Fe redox states and the variable amounts of Fe(III)–PS complexes likely present. The extent of enrichment with light isotopes in the shoot material observed is significantly smaller than that found in previous work (Guelke and von Blankenburg, 2007; Kiczka et al., 2010b) and this observation suggests significant uptake of Fe in its reduced form. Ferrous Fe is taken up without the need for preceding phytosiderophore-facilitated solubilisation in the rice rhizosphere (Ishimaru et al., 2006).

The rice does not show significant enrichment with light isotopes in the grain in disagreement with previous work on oat (Guelke and von Blankenburg, 2010; Guelke-Stelling and von Blanckenburg, 2012). At present, this difference is not easily explainable and further work is needed. Iron, similar to Zn, is transported into the symplasm via the apoplasm before grain-loading. The lack of isotopic fractionation could suggest a quantitative transport of complexed Fe (III) from the soil solution to the grain.

4 Conclusions

We find large negative fractionation of Zn during the translocation of from shoots into grain. The direction and magnitude of the shoot to grain fractionation is consistent with other studies and with the concept of enrichment with light isotopes into higher levels of the food chain. The different extend of isotope fractionation between Zn in the soil leach and the total above ground plant suggests that a mixture of different Zn species are taken up depending on the soil conditions, likely including free Zn2+ and PS–Zn complexes. Within experimental error, Fe isotopes showed the same isotopic pattern between the different plant reservoirs and in rice grown in the two different soil environments. Finally, the different isotope patterns observed for Fe and Zn suggest that the remobilisation and subsequent transport does not occur via the same mechanism.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to Jean, Caroline, Olivier and Jules. The work was partly funded by a grant from the UK's Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC, Grant Ref. BB/J011584/1) under the Sustainable Crop Production Research for International Development program, a joint multinational initiative of BBSRC, the UK Government's Department for International Development and (through a grant awarded to BBSRC) the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We acknowledge financial support from Stanford University (to DJW through the Cox Visiting Fellowship) and from Imperial College London (to TA through a PhD scholarship). Rothamsted Research is an institute of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council of the UK.