1 Introduction

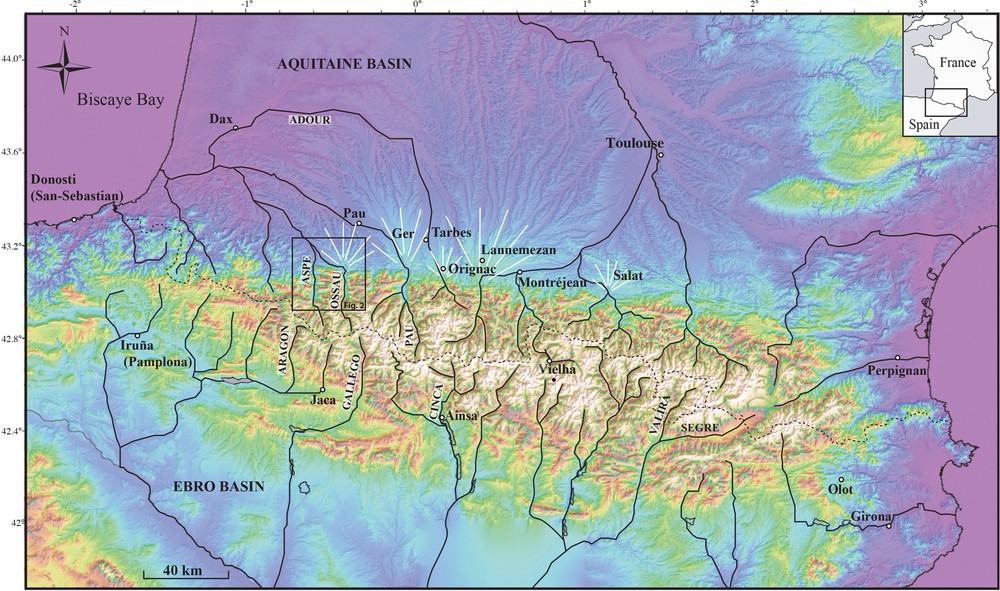

Foothill (or piedmont) deposits record climatic and tectonic fluctuations that control the growth of mountain chains (Beaumont et al., 2000; Hovius, 2000; based on Babault et al., 2005). Indeed, incision and aggradation in fluvial networks are ruled by three main factors: (i) base level changes (Blum and Torqvist, 2000), (ii) climate oscillation (Molnar, 1994), and (iii) tectonic activity (e.g., Burbanks et al., 1994). The nature and thickness of these deposits provide information on the intensity of erosion, the efficiency of sediment transport and the amount of deformation. In the North Pyrenean foothills, the last main fluvial depositional phase occurred between the Late Miocene and the Early Pleistocene, leading to the formation of fans more than 100 m thick (from west to east, the Ossau, Ger–Pau, Adour, Lannemezan, Ger and Salat fans; Fig. 1). These fan deposits are silicoclastic and differ from earlier formations by their lack of a carbonate fraction. They rest on the Aquitanian molasse whose top can be attributed to the Late Serravallian due to the occurrence of the MN 8 biozone at Montréjeau–Saint-Gaudens in the Lannemezan fan (Antoine et al., 1997; Crouzel, 1957). Near Lannemezan, the top of the series is ascribed to the Plio-Quaternary transition owing to charcoals collected at the margin of the fan (Dubreuilh et al., 1995).

Topography of the Pyrenees (SRTM DEM). Major rivers draining the Pyrenees are also shown.

During the Pleistocene, the foothills underwent a strong incision stage that led to the formation of five main alluvial sheets (Barrère et al., 2009). The correlation of these sheets between valleys is based solely on their elevation. In continuity with the moraine fronts in the valleys, some of these alluvial sheets are clearly controlled by glacial pulses. Although numerous absolute ages are now available on the glacial deposits (review in Calvet et al., 2011), the chronology of the North Pyrenean alluvial sheets is still based on relative criteria, such as the degree of weathering of pebbles and topsoil eluviation (Alimen, 1964; Hubschman, 1975; Icole, 1974). Until recently in the Pyrenees, the only absolute dating available on fluvioglacial terraces concerned the southern flank of the belt (Lewis et al., 2009; Peña et al., 2004; Sancho et al., 2003, 2004; Stange et al., 2013; Turu I Michels and Peña Monné, 2006).

In this study, we make use of the 10Be cosmonuclide method to carry out the dating of one of these remnant terraces. Together with works by Stange et al. (2014) and by Delmas et al. (2015), this represents the first attempt of absolute dating of a remnant terrace on the northern flank of the Pyrenees. Investigations are conducted on the main terrace shaped by the Aspe River near Oloron-Sainte-Marie. Apart from their input to the geological mapping, the resolution of this new dating allows a detailed discussion of terrace formation in the framework of the Würmian glaciation. More particularly, we discuss the genetic link between the alluvial system and climatic forcing. In addition, this age yields a crucial time constraint on the Late Pleistocene tectonic activity in the area.

2 Geological and morphological setting

2.1 Morphostructural setting

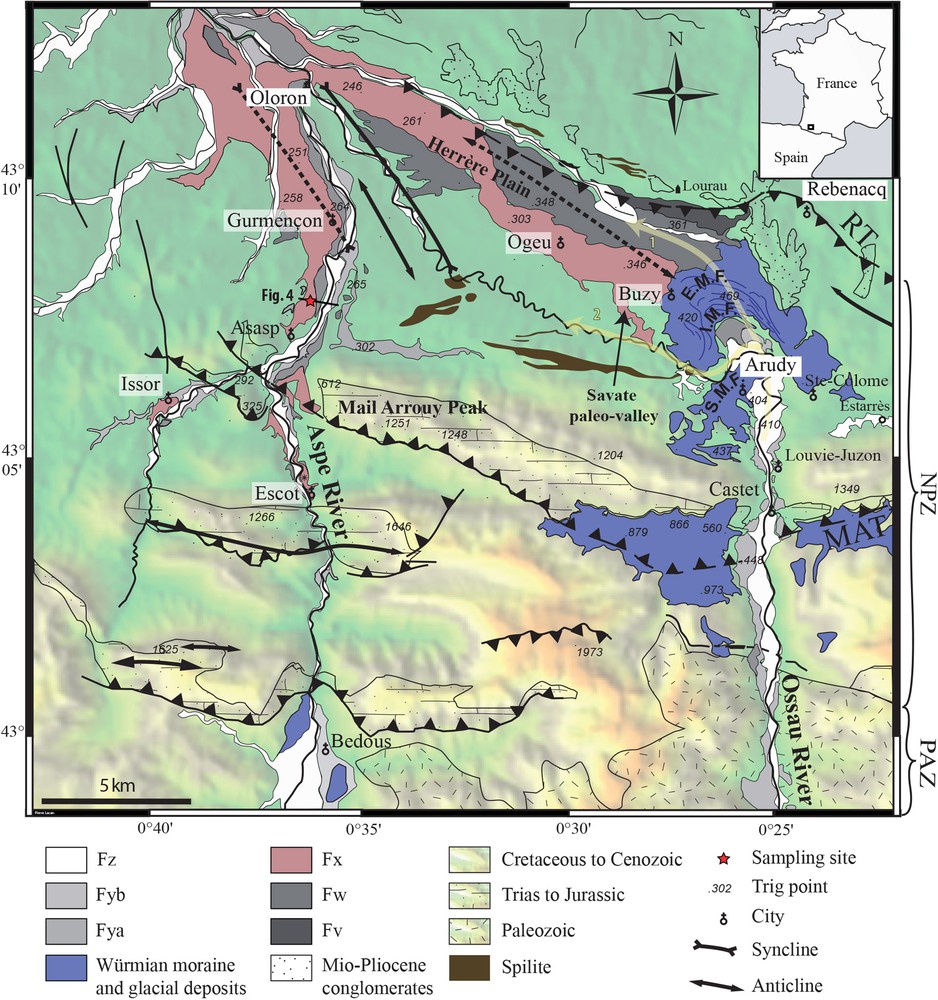

We focus on two rivers, the Ossau and Aspe Rivers, of the mountain front near the northern limit of the North Pyrenean Zone, in the Chaînons Béarnais. It is marked here by the Mail Arrouy thrusted anticline that reaches an elevation of 1400 m (Fig. 2). North of the Mail Arrouy, the piedmont is formed by hills of moderate relief, with heights decreasing from > 500 m to 300 m towards the north. This piedmont zone is notched in its middle part by a 2–3-km wide depression trending WNW–ESE, known as the Herrère plain, which is a former course of the Ossau River. The catchments of the Aspe and Ossau Rivers that rise in the Axial Zone of the Pyrenees, show outcrops of sedimentary, metamorphic and magmatic rocks of Palaeozoic age. Blocked at Arudy by the terminal moraines of the Ossau Glacier (e.g., Barrère, 1963), the Ossau River now flows more to the south of the Herrère plain (Fig. 2; e.g., Depéret, 1923). It follows first an east–west direction and then bends towards the NNW before joining the Aspe River near Oloron-Sainte-Marie (Fig. 2). To the west, the Aspe River runs roughly north–south at the outlet of the Aspe Valley. Both rivers are deeply entrenched into the bedrock.

Quaternary alluvial terraces of the Aspe and Ossau rivers (after Castéras et al., 1970) plotted on the SRTM DEM. MAT: Mail Arrouy Thrust; RT: Rébénacq Thrust; EMF: External Moraine Front; IMF: Inner Moraine Front; SMF: Moraine Front. The arrows indicate the former (1) and the current (2) courses of the Ossau River.

The main structural feature consists of thrusts striking approximately east–west (e.g., Castéras et al., 1970; Fig. 1). To the north, the south-dipping Rébénacq thrust is picked out by the contact between Triassic evaporites and a Late Cretaceous flysch at Rébénacq to the northeast. Its structural trace disappears to the west.

Farther south, the southward facing Mail Arrouy thrust (MAT) cuts across the area over a distance of more than 30 km, and dies away to the west against N140°E-striking faults (e.g., Canérot and Lenoble, 1993). Capped by the Aptian limestones, the Triassic marls at the core of the structure indicate a throw of several kilometres (Fig. 2).

Smaller right-lateral overthrust folds are also located in the Late Cretaceous flysch between the Rébénacq and Mail Arrouy thrusts (Castéras et al., 1970). These folds strike N135°E, and show axial lengths ranging between 5 and 10 km with amplitudes of several hundreds of metres. To the north of the Rébénacq thrust, some remnants of Mio-Pliocene conglomerates lie unconformably above the Late Cretaceous flysch.

Using remnant terraces, Lacan et al. (2012) evidenced a Pleistocene tectonic reactivation of the MAT. Above the thrust, the terrace infills are only a few metres thick and are deposited in the bedrock. On the contrary, above the footwall, the terrace is an aggradational terrace exhibiting a 20 to 30-m thick infill. This geometry reflects an aggradation in the footwall and erosion in the hanging wall of the MAT. Secondly, the incision is deeper in the hanging wall than in the footwall and finally, topographic measurements reveal a warping of the highest and oldest terraces. This led Lacan et al. (2012) to propose that a Late Pleistocene reactivation of the MAT caused a local uplift above the thrust.

A similar terrace geometry is also observed along the smaller Issor valley that crosscuts the MAT 2 km to the west of the Aspe Valley. Such geometry also argues for a recent tectonic activity of the MAT (Lacan et al., 2012).

2.2 Geometry and chronostratigraphy of alluvial and glacial deposits

We use the nomenclature of the French Geological Survey (BRGM) 1/50,000 geological maps to label the terrace levels and remnant moraines. F are fluvial terraces and G are glacial deposits. z, y, x, w, v give information on the relative age of the markers from the youngest to the oldest, z being the youngest.

The former drainage network is recorded in the relief at the outlet of the Aspe Valley by four terraces labelled Fya, Fyb, Fx and Fw on the Oloron-Sainte-Marie geological map (Castéras et al., 1970). A higher level Fv is only preserved in the Herrère plain near Lourrau (Fig. 2 and Appendix A).

The farthest advance of ice reached Arudy at the outlet of the Ossau Valley (Fig. 2; Barrère, 1963; Mardonnes and Jalut, 1983; Penck, 1883; Ternet et al., 2004). Near Arudy, remnants of three generations of moraines have been recognized. Two series of weathered moraines occupy an outer position at Sainte-Colome (Hubschman, 1984) and at Lourau (Hétu et al., 1992; Fig. 2), more than 80 m above the Hérère plain. Well preserved in a lower position, the youngest Arudy complex is unweathered and consists of several frontal moraines. The outermost moraine extends as far as Buzy, a few kilometres to the west of Arudy, and is connected to the remnant Fx terrace on the Herrère plain (EMF in Fig. 2). An inner moraine surrounds Arudy (IMF in Fig. 2).

More details on the chronostratigraphy of alluvial and glacial deposits appear as supplementary material in the online version, see Appendix A.

3 Dating of the Late Pleistocene fluvioglacial level of the northern Pyrenean foothills

3.1 Principle and sampling site

This section appear as supplementary material in the online version, see Appendix A.

3.2 10Be data and interpretation

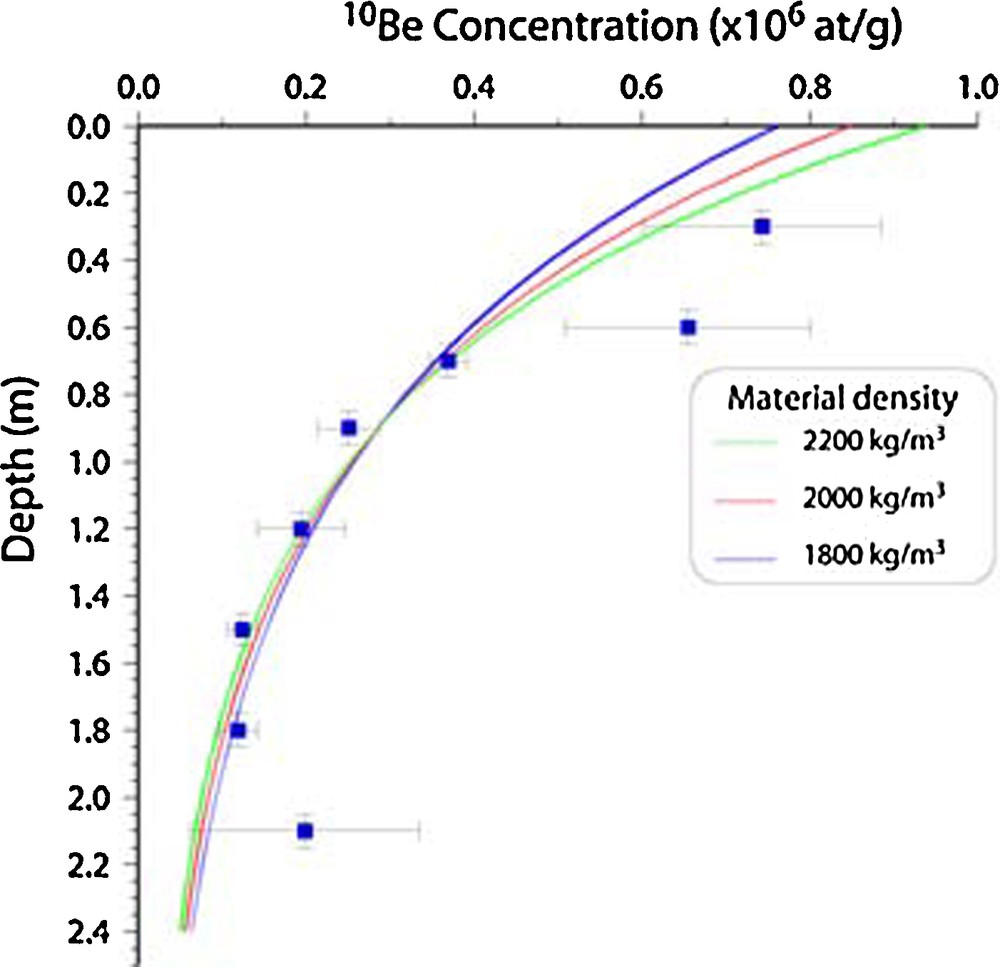

To analyse the depth profile, we performed numerical inversions of the data in which we fixed the erosion rate as either negligible (cf. Section 3.1) or 10 m/Ma, the same order of magnitude as the values obtained in southeastern France (Siame et al., 2004). The inversion depends on the bulk density of the geological formation. Following Hancock et al. (1999), and considering an average clast/pebble density of 2600 kg/m3 and a bulk matrix density of 1800 to 2000 kg/m3 (∼30% porosity), the bulk terrace material density can be estimated at between 2000 and 2200 kg/m3. We used the CRONUS production rate (Balco et al., 2008) (see Table 1), the attenuation lengths of Braucher et al. (2003), and a 10Be half-life of 1.36 Myr (Chmeleff et al., 2010; Korschinek et al., 2010). The various inversions calculated here fit the data satisfactorily and agree with an age of 18 ± 2 ka. As expected, changing the erosion rate does not substantially modify the curve shape (Fig. 3). Best-fit curves are generally obtained for erosion rates of the order of 10 m/Ma. Some samples (for example the deepest one) do not fit exactly the best-fit curve likely because part of their 10Be content comes from inheritance. Inversions made with another program (Hidy et al., 2010), based on Monte-Carlo inversions indicated limited inheritance (less than ∼7000 at/g) and similar best-fit ages.

Sample 10Be concentrations. Carrier is Nishizumi Be-01-5-3 standard 10Be/9Be 6320 (E-15). Sample position is 43°07′57.3′′N 0°36′15.0′′W at an elevation of 245 m. Topographic shielding is less than 1‰. Production is 5.4 at/g/yr (calculated with CRONUS Web calculator) (Balco et al., 2008).

| Name | Depth (m) | Sample weight (g) | 10Be (at/g) | ± |

| PI-030 | 0.3 | 10.1103 | 74,310 | 14,113 |

| PI-060 | 0.6 | 7.971 | 65,498 | 14,608 |

| PI-070 | 0.7 | 108.267 | 36,906 | 2236 |

| PI-090 | 0.9 | 38.372 | 25,073 | 3633 |

| PI-120 | 1.2 | 21.3256 | 19,396 | 5235 |

| PI-150 | 1.5 | 80.695 | 12,379 | 1764 |

| PI-180 | 1.8 | 62.394 | 11,890 | 2326 |

| PI-210 | 2.1 | 6.8759 | 19,837 | 13,662 |

10Be activity vs. depth profile and best-fit curves depending on the material density. Note that two curves (cf. Table 2) are drawn for each density considered, but they are too closely similar to be distinguished on this graph.

In summary, the cosmogenic nuclide concentration evolution at depth gives a reliable age of 18 ± 2 ka BP for the terrace surface.

4 Discusion

4.1 Timing of the incision of Fx

Based on weathering and pedogenetic criteria, Hubschman (1984) ascribed the Fx terrace in the northern Central Pyrenees to the Würmian glaciation. Gangloff et al. (1991) extrapolated this result towards the west into the sampling area. Our results agree with this. The cosmonuclide dating of Fx at Gurmençon yields an age of 18 ±2 10Be kyr BP, showing that the terrace is indeed not coeval with the Rissian glacial cycle (MIS 6), as postulated by, e.g., Alimen (1964). This inappropriate assignment remains mentioned on the geological maps of the region (Castéras et al., 1970; Goguel, 1963; Ternet et al., 2004).

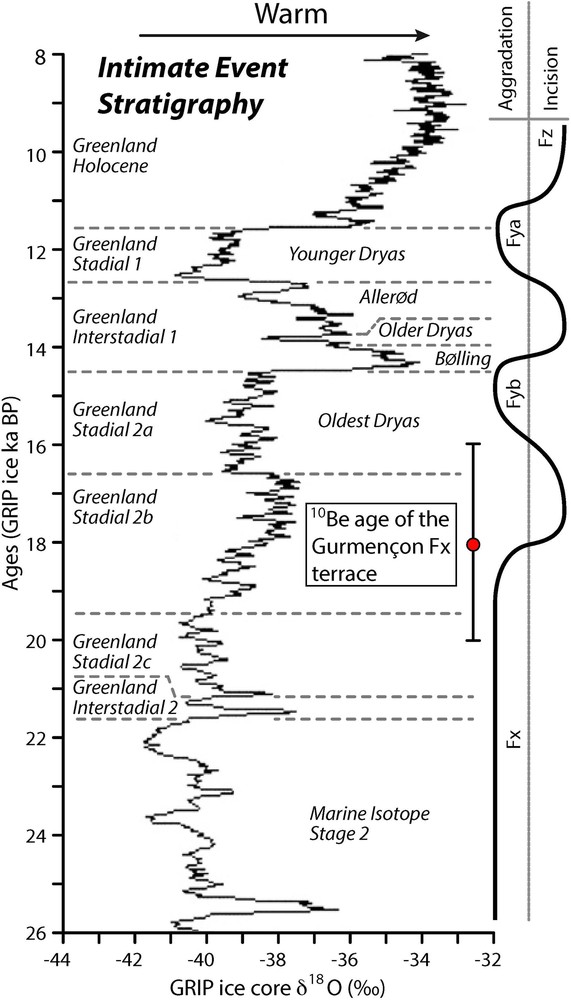

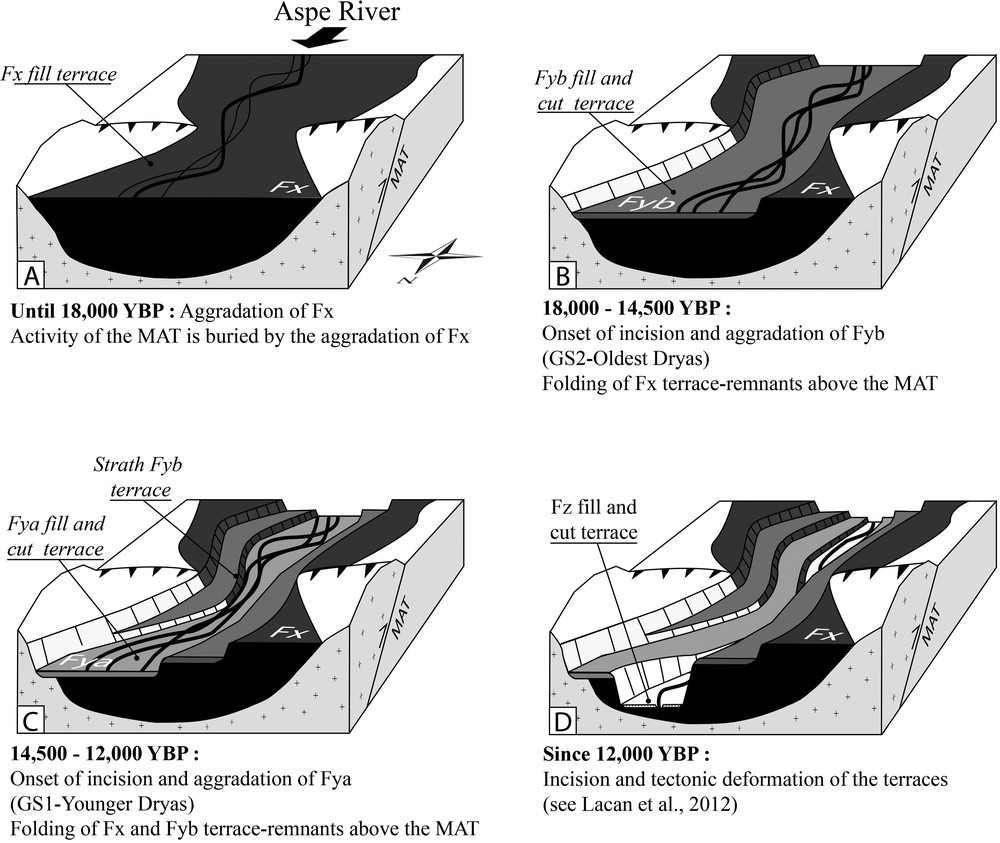

The 10Be cosmogenic dating of the Fx terrace at Gurmençon provides a better constraint on the timing of the fluvioglacial sequence within the Würmian glacial cycle and allows us to address the river response to short climatic oscillations. By using the top of the terrace, we date the end of the aggradation, and therefore presumably also the onset of incision. The aggradation lasted until the end of the global Last Glacial Maximum (LGM; Mix et al., 2001; Yokoyama et al., 2000). The initiation of incision is coeval with the onset of the warmer episode at the end of the stage GS2b (16.5–19.5 kyr; Figs. 4 and 5) of the intimate event stratigraphy (Lowe et al., 2008), which corresponds in the Pyrenees to a marked episode of glacier retreat (Delmas, 2005; Delmas et al., 2008). Similar records are found along the Garonne River remnant terraces (Stange et al., 2014). By extrapolating this climatic correlation with the younger terraces, we may suggest that the Fya and Fyb terrace levels of the geological maps have been shaped during the colder GS-2a (Oldest Dryas, 14.5–17 kyr) and Gs-1 (Younger Dryas, 11.5–12.5 kyr; Figs. 4 and 5) events, by a lateral planation of the river. This aggradation followed an entrenchment in the former (higher) terrace during the climatic transition. The current Fz terrace appears to postdate the Younger Dryas (GS-1) glacial episode.

Tentative correlation between the 10Be exposure age of abandonment of the Fx terrace level at Gurmençon (Western Pyrenees) and North Atlantic paleo-temperature oscillations derived from the GRIP ice- core chronology (based on Johnsen et al., 2001). High δ18O values correlate with relatively warmer conditions.

Sketches showing the evolution of filling and incision of river terraces along the Aspe River in relation with climatic and tectonics events from 18,000 yr to the present.

The morphology of Fy with respect to Fx at Gurmençon also shows that the Aspe River underwent successive episodes of valley floor widening and narrowing. Parts of the valley floor that were abandoned during episodes of narrowing and subsequent river entrenchment are preserved on valley flanks as cut-in-fill terraces. At the transition from relatively cold to temperate conditions, fluvial forms were gradually transformed from a periodically high-energy multi-channel type to a regular, low-energy, single-channel pattern (e.g. Vandenberghe, 2008). The former braided type is characterized by intense lateral migration, rather than by deep vertical erosion. In the study area but also in the Garonne catchment (Stange et al., 2014), this results in a well-expressed morphology with wide extensive floodplains, associated with terraces such as shown by the Gurmençon Fx remnant. By contrast, the linear and confined meandering channels lead to the incision of valleys with small width–depth ratio and build floodplains of limited lateral extent such as in the case of Fy.

Elsewhere, many catchments in Europe and Turkey provide geological evidence for valley incision concomitant with the onset of interglacial conditions (for instance, Doĝan, 2010; Murton and Belshaw, 2011; Nivière et al., 2006; Olszak, 2011; Regard et al., 2006; van Balen et al., 2010). Short phases of fluvial instability would occur at the transition from relatively cold (periglacial) to warm (temperate) periods, caused in particular by variations in the stream power of rivers, by soil formation and degradation and by the development of a vegetation related to climatic change (e.g., Schumm, 1977; Vandenberghe, 1993; Vandenberghe, 1995). Major valley incision phases have been attributed to periods of glacial to interglacial warming on the basis of the stratigraphic position of interglacial deposits lying at the base of individual terrace sediment sequences (Vandenberghe, 2008). Murton and Belshaw (2011) pointed out that such successions merely indicate that valley incision precede interglacial valley filling; it is not possible to distinguish whether incision occurred during the climate warming or during the prior glacial conditions. Our dating (see Table 2) unambiguously confirms that incision started in the northern Pyrenean foothills with the warmer episode of stadial stage GS2b.

Evaluations of terrace age following material density and erosion rate. An erosion rate of 10 m/Ma is about the best-fit value.

| Material density (kg/m3) | Erosion rate (m/Ma) | Age (yr) |

| 1800 | 0 | 14,200 |

| 2000 | 0 | 15,800 |

| 2200 | 0 | 17,500 |

| 1800 | 10 | 15,300 |

| 2000 | 10 | 17,500 |

| 2200 | 10 | 19,800 |

4.2 Timing of the aggradation of Fx

Our dating does not give any specific information on the time interval of the aggradation of Fx. The sediment stratigraphy and geochronology indicate that the warm and moist periglacial conditions characteristic of MIS 3 correspond to a time of fluvial aggradation in the Northwest European lowlands (van Balen et al., 2010). The extensive Garonne terrace complexes formed under cold-climate conditions (Stange et al., 2014). The position of the Fx remnant terrace on the Herrère plain with respect to the Ossau glacier, located along the former course of the Ossau River, could shed some further light on this issue.

Because the Fx remnant terrace on the Herrère plain is connected with the Buzy moraine front, the top of this terrace is necessarily older than 30–34 ka cal BP (see Appendix A), and thus significantly older than the last aggradation in the Fx terrace located in the Aspe valley (dated in this paper). This remnant terrace is nevertheless connected with Fx downstream of Oloron-Sainte-Marie owing to a steeper gradient (9.5‰ versus 7‰). As already observed farther east in Ariège (Delmas et al., 2011), this shows that a chronology based on an elevation criterion is rather inappropriate at the scale of the intra-Würmian climatic oscillations. Although these two Fx terraces (Aspe and Herrère) are morphologically interconnected, they are not exactly contemporary. Indeed, after the glacial recession dated by 14C at around 27 ka (i.e. MIS 3), the Ossau River shifted south (Fig. 2) and no longer contributed to the building of the Fx terrace on the Herrère plain. If we invoke a climatic-driven aggradation, the onset of aggradation of Fx should be more or less coeval in the Aspe and Ossau valleys. However, the aggradation of Fx downstream of the Ossau glacier has ceased earlier on the Herrère plain due to the valley's abandonment. Since the Herrère Fx terrace is much thinner than the Gurmençon Fx terrace (ca 20 m versus 60 m; e.g., Alimen, 1964), this suggests that aggradation has continued along the Aspe River during the 27–18-ka time interval (which agrees with our dating results, see Table 2). This implies that aggradation of Fx at this location in the North Pyrenean foothills would have continued during the whole of the colder MIS 2 interval. More accurately, aggradation continued until the end of the Global LGM, while the incision started as early as the GS2b interstadial. In the framework of our proposed chronology for the Fy cut-in-fill terraces, the reduced thickness of deposits could be interpreted in the context of the very short stage GS-2a (Oldest Dryas colder episode, Fig. 4) that restricted sedimentary storage in the upper Aspe valley.

4.3 Climatic forcing on the Aspe River morphology

The results of our study confirm the prevailing theory of river cyclicity as a response to climate transitions (Vandenberghe, 2008). Short phases of fluvial instability lead to major incisions associated with climate warming during the interval from glacial to interglacial periods, while limited incisions take place during cooling (e.g., Bridgland, 2006; Bridgland and Westaway, 2008; Maddy et al., 2001; Stemerdink et al., 2010). This pattern of cyclicity is consistent with the numerical models of Tucker and Slingerland (1997). The sediment supply increases in response to enhanced runoff intensity due to climate change coupled with the concomitant rapid expansion of the channel network caused by ice retreat.

Stratigraphic studies in Alaska, northern Canada, and Siberia indicate that global warming during the last glacial to interglacial transition triggered a major phase of thermokarst activity associated with mass wasting linked to the degradation of ice-rich permafrost (Murton, 2009). In turn, the mass wasting (e.g., debris flows, solifluction, and gelifluxion processes that affect valley slopes) resulted in the deposition of abundant sediments in lowlands (Murton, 2001). Such a climatic transition would have triggered an aggradation along rivers. The low gradients of the valley profiles were adjusted such that rivers transferred fine materials out of the basins, but lacked the competence to remove gravel, which therefore accumulated on the floodplains. This model attributes incision and planation to very cold and arid permafrost conditions, when rivers discharges were reduced and hillslopes supplied limited volumes of stony debris into valley bottoms. The geometric and chronological setting of alluvial deposits in the Aspe valley does not display this pattern. Since the river was situated in a relatively high position in its catchment where the stream gradient remained steep, it could have been less sensitive to climatic disturbances than in the lowland.

4.4 Tectonic forcing on the Aspe River's morphology

Lacan et al. (2012) interpreted the folding of the dated terrace as the consequence of a Late Pleistocene reactivation of the Mail Arrouy thrust, which is located in the most seismically active area of the Western Pyrenees. Here, our dating demonstrates that deformation of the terraces above the Mail Arrouy thrust occurred after 18 ± 2 ka. The recent tectonic activity of Mail Arrouy thrust is consistent with the marked seismicity of the area highlighted by the Arette (M = 5.3 to 5.7; 1967) and Arudy (M = 5.1; 1980) earthquakes. Even if the MAT is too thin-skinned and too small to cause major seismic events, it nevertheless reflects the persistent nature of this tectonic activity during the Late Pleistocene.

The tectonic signal recorded in Fx corresponds to the amplitude of 8 m of the fold above the MAT (Lacan et al., 2012). This value equals the difference in elevation of Fx with respect to the river between the footwall (36 m) and the hanging wall (44 m). The wavelength of the fold reaches 2800 m. This value shows that the mid-term (0–18 ka) tectonic uplift accounts for only 1/6 of the whole river incision. At this time scale, the river course had not been disturbed. This suggests at the scale of the Late Wurmian (i) that the erosive power of the river was strong enough to balance tectonic forcing and (ii) that climatic forcing is the driving forcing in the river morphology unless the transition of fluvial styles (braided, meandering) may have been stimulated or initiated due to tectonically induced gradient changes.

A fault scarp due to a surface rupture could have temporally disturbed the riverbed. An additional survey, including systematic and precise sedimentological and palaeoseismological studies is required to evidence it. But the morphologic setting, characterised by steep hill slopes along the valley and a large erosive power of the river, does not favour the preservation of such a tectonic scarp. Due to the magnitude of the maximum possible earthquake in the area (M 6, Dubos-Sallée et al., 2007), a potential rupture surface would not overpass two decimetres in elevation (Wells and Coppersmith, 1994). This height is not strong enough to disturb the course of such a river. Moreover, the shape of the fold in Fx suggests that the leading fault is still blind (Lacan et al., 2012).

5 Conclusion

We present here a 10Be dating of an alluvial terrace in the Northern Pyrenees. This terrace (Fx) has been widely mapped in the foothills of the Western Pyrenees, being firstly ascribed to the Rissian glaciation (Depéret, 1923). Subsequent studies of the weathering of these alluvial deposits suggested a Würmian age (Icole, 1974; Hubschman, 1984). 10Be Dating of the Fx terrace at Gurmençon yields an age of 18 ± 2 10Be kyr, thus supporting the interpretation given by Icole (1974) and Hubschman (1984), and providing more precise constraints. However, the Fx remnant terrace on the Herrère plain is significantly older than the last aggradation in the Fx terrace located in the Aspe valley (dated in this paper). Nevertheless, these terrace remnants merge on the same level downstream of Oloron-Sainte-Marie. This shows that a morphologic chronology based on an elevation criterion is rather inappropriate at the scale of the intra-Würmian climatic oscillations.

This dating result allows us to address two kinds of issue. Firstly, the close link with Late Pleistocene climatic events suggests that high-standing fill terraces, such as Fx follow a long period of aggradation, which probably spans the entire Würmian glaciation. This is because the top of the Fx fill terrace was aggraded until the end of the global LGM, and its incision only began at the onset of the warmer oscillation GS2b. The data also suggest that the lower strath terraces were built during the short late glacial climatic oscillations, with the aggradation of Fya and Fyb during the Oldest Dryas and Younger Dryas cold episodes, respectively. Incision of these two levels occurred during the consecutive warmer episodes, namely the Bölling/Allerød and the Holocene. Overall, repeated climatic oscillations induced several cycles of valley filling and subsequent downcutting associated with superimposition, and led to the present-day complex of crosscutting buried drainage networks.

Secondly, Lacan et al. (2012) showed that the Fx terrace is warped above the Mail Arrouy thrust. This warping post-dated the abandonment of the Gurmençon Fx terrace, which leads us to invoke a Late Pleistocene fault reactivation in this most seismically active area of the Western Pyrenees.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Bernard Monod and Ronan Madec for their help with the field work. Dr M.S.N. Carpenter post-edited the English style. Finally, we would like to thank Bernard Delcailleau and Ronald van Balen for reviews and Yves Lagabrielle for editing and improving the manuscript.