1. Introduction

More than half a century ago, Hench et al. [1971] developed the first bioactive glass composition, later termed Bioglass 45S5. This material is generally considered to be the starting point for the entire field of bioactive materials [Jones 2013], which besides glasses includes other materials such as glass-ceramics [Vogel and Höland 1987], ceramics and even some metals such as pre-treated titanium [Kim et al. 1997]. Bioglass 45S5 consists of 46.1 SiO2, 2.6 P2O5, 26.9 CaO and 24.4 Na2O (in molar percentages; composition often quoted in weight percentages: 45 SiO2, 6 P2O5, 24.5 CaO and 24.5 Na2O). Larry Hench selected the components for good reasons: Na, Ca and P all are physiological elements naturally present in the human body, and Si is an essential element present in the body at low concentrations. His reasoning was that a material consisting of these elements would integrate well with the body and not be encapsulated into interfacial fibrous tissue [Hench 2006]. This was the natural starting point, and subsequent results proved him to be right: Bioglass 45S5 became the first synthetic material to form an integrated bond with human body tissue including not only bone [Hench and Paschall 1973] but also soft tissue [Hench 1991]. It was further shown that ions, particularly soluble silica species, released from the glass stimulated osteoblast proliferation [Xynos et al. 2000] and upregulated various osteoblast genes, including some involved in metabolism and bone homeostasis [Xynos et al. 2001]. The integration with body tissue is possible because of a biomimetic apatite surface layer which forms when Bioglass 45S5 is in contact with physiological solutions, and which body cells, such as osteoblasts, adhere to and proliferate on [Hench and Paschall 1973].

Despite Hench’s compositional reasoning, the development of Bioglass 45S5 can be described, to some extent, as an educated guess. Larry Hench himself often told the story of how his research on finding glass compositions suitable as implant materials was sparked by a chance encounter with a colonel of the US Army [Hench 2006]. This colonel knew from his experience during the Vietnam war that many wounded soldiers lost their limbs simply because their bodies rejected the implant materials available at the time, and he challenged Larry Hench to use his knowledge in glass science to develop a material that would be accepted by the human body. Larry Hench took this challenge, and after liaising with colleagues in the medical field successfully applied for funding by the US Army and embarked on a research project that would lead to Bioglass 45S5. There was, however, no previous work to build upon, no other known synthetic materials, inorganic or organic, which were known to chemically bond to body tissue. Today, researchers from many fields, including cell biology, medicine, bio-medicine or dentistry, are actively researching bioactive glasses. Nonetheless, it was materials scientists and engineers such as Larry Hench himself, a ceramic engineer, who we have to thank for developing the first bioactive glasses [Hench 2006].

Bioactive glass optimisation is still a topical issue, even fifty years since the first successful studies. The reason for the successful development of bioactive glass compositions is rooted in their glassy nature, as glasses are excellent solvents for almost all elements. Glass properties depend on the elements included, their concentrations and the resulting atomic structure. Today, the development of new bioactive glass-based implants is highly interdisciplinary and partly guided by our enhanced understanding of the roles of various elements in cellular processes. The first bioactive glasses consisted of five elements Na, Ca, Si, P and O; today, more than 30 elements have been studied for their potential therapeutic effects in glasses intended for implants [Hoppe et al. 2011; Hupa and Karlsson 2017].

Hench-type bioactive glasses are silicate glasses often containing smaller amounts of a second glass former, phosphate or borate. Essentially, the choice of the main glass-forming components in bioactive glasses is based on our understanding of the chemistry and technology of conventional soda-lime silicate glasses. In addition, recent advances in molecular biology have encouraged researchers to explore whether dopants can give additional benefits for tissue regeneration. However, increasing the number of elements in bioactive glasses requires a detailed understanding of the glass structure and its impact on the properties to find and optimise the most suitable composition for a specific clinical application.

Selected bioactive glass compositions not only need to provide the desired properties for the device when in contact with the human body, the compositional choice also needs to allow for economic and reliable production of the material. This review discusses various approaches taken during the development and optimisation of bioactive glass compositions. Emphasis is put on the impact of structural analysis techniques for providing an understanding of the bioactive glass structure at an atomic level and compositional modelling as a powerful tool for tailoring new bioactive glass compositions.

2. Glass development based on statistical series

When optimising bioactive glass compositions for a particular application, extensive experimental studies are needed to confirm that the compositions, which typically are multicomponent, are suited for the purpose, especially with regard to material/tissue interactions. This includes studies such as in vitro degradation, mineralisation and ion release [Nommeots-Nomm et al. 2020], various cell culture studies [Jablonská et al. 2020] and, ultimately, animal experiments and clinical studies. Besides these chemical and biomedical properties, glass physical properties need to be considered as well, and particularly high-temperature processing of the glass into the desired product shape is an additional challenge. For example, the melt-derived bioactive glasses used clinically are prone to devitrification due to their low contents of glass network formers. Here, the current interest in developing three-dimensional porous constructs (typically called “scaffolds”) and fibre-based products that mimic tissue structure such as extra cellular matrix has called for bioactive glass compositions that allow flexible high-temperature processing without compromising bioactivity properties. Once experiments have been performed on a sufficiently large set of samples, computerised optimisation routines offer a means to find compositions that satisfy a set of predetermined properties [Vedel et al. 2009; Westerlund et al. 1983], and statistical or other models describing the property/composition relations are useful tools for composition optimisation.

The properties of bioactive glasses have been characterised in numerous studies. Hench and colleagues’ systematic in vivo studies identified composition ranges in the system Na2O–CaO–P2O5–SiO2 that chemically bonded to bone and soft tissues [Hench and Wilson 1984]. Also, several systematic studies discuss the impact of gradual substitution of one element for another on the properties of well-known commercial bioactive glasses such as Bioglass 45S5 [Blochberger et al. 2015; O’Donnell et al. 2010; Tylkowski and Brauer 2013] or BonAlive S53P4 [Massera et al. 2012; Massera and Hupa 2014; Wang et al. 2017]. These studies with structural analyses (discussed further below) aim to identify the effect of one particular glass component on the bioactive glass properties. The effect of ionic substitutions is discussed in detail in Section 4.

For glass optimisation using regression analysis, no systematic changes (such as replacing one element by another) are needed. Instead, a sufficiently large set of compositions is required to mathematically describe the composition/property relationship. Here, these compositional series are described as “statistical”, as they include variation of several or potentially all components. In this approach, the impact of each component on the glass properties was estimated using linear functions of the molar composition within certain composition limits. Considering that each constituent has a specific effect on each property, overall glass performance prediction requires that all relevant properties can be expressed as functions of the composition. Over the years, several composition/property relations have been developed for various properties of conventional soda-lime glasses, as described in various text books [Musgraves et al. 2019; Scholze 1991].

In the group of Kaj Karlsson at Abo Akademi University in Turku, Finland, this regression approach was used successfully in the design of bioactive glasses. Andersson et al. [1990] used 16 statistically selected compositions within the system 46–65.5 SiO2, 15–30 Na2O, 11–25 CaO, 0–8 P2O5, 0–3 Al2O3 and 0–3 B2O3 (in wt%) to study the impact of glass composition on bone bonding when implanted into rat tibia for eight weeks. Also, the bone contact type was evaluated for each composition. In addition, they measured the weight loss in vitro and analysed the quality of silica-rich and hydroxyapatite surface layers formed during in vitro immersion. Based on these characteristics, the glasses were divided into groups of comparable bone-bonding capability, which was rated by a numerical value (ranging from 1 to 6) and referred to as the reaction number (RN). This approach made it possible to quantifying the property combinations to achieve a composition dependency model for bioactivity. Andersson et al. used regression analysis of the observations to describe RN as a function of the glass composition given in weight percentages (1). The idea was to use this calculation to select additional promising compositions without having to go through the full set of experimental characterisations for large sets of glass compositions. Instead, only compositions giving RN values of 5 or higher were assumed to fulfil the criteria of bioactivity and bone-bonding and would be tested experimentally.

| (1) |

Brink and co-authors used a similar approach of a statistical series of 26 compositions in the system Na2O–K2O–MgO–CaO–B2O3–P2O5–SiO2 to establish the impact of glass composition on high-temperature processing [Brink 1997a] and in vivo properties [Brink et al. 1997] of bioactive glasses. The first bioactive glasses spontaneously crystallised during high temperature processing, which made the sintering of glasses into porous scaffolds or the drawing of continuous fibres, a challenge. K2O and MgO were assumed to improve the hot-working properties of these bioactive silicate glasses (39–70 wt% SiO2), similar to what is known for conventional soda-lime glasses. Al2O3 was not included in this series as contents of around 2 wt% in the glass had been shown to induced adverse effects on bone-bonding [Andersson et al. 1993]. The glasses were studied in rabbit tibia for 8 weeks, after which bone-bonding was evaluated and the presence of silica-rich and hydroxyapatite surface layers was investigated. These in vivo observations were rated by numerical values from 1 to 4, referred to as index of surface activity (ISA) and subsequently included in a regression analysis as a function of the glass composition in weight percentages (2) [Brink et al. 1997].

| (2) |

Later, several other property/composition regression models were published to describe the physical and in vitro properties of additional bioactive glasses [Arstila et al. 2008; Vedel et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009]. Vedel et al. [2009] used these models to optimise new bioactive glasses with pre-specified properties. Here, bioactive glasses 45S5, S53P4 and 13–93 and some of the new optimised glasses were implanted in rat femur for up to 8 weeks. Some results from these in vivo studies have subsequently been discussed by Fagerlund et al. [2013] and showed that, in general, in vitro ion release from the glasses and the calculated RN and ISA values correlated with the observed reaction layer formation in vivo. These results suggest that regression models provide valuable information for composition optimisation.

One criticism of the RN and ISA models described above is that they are based on the composition in weight percentages. If we want to relate the findings of such studies to the atomic glass structure, the use of models based on the molar glass composition (i.e., molar percentages) would be much more insightful. It might even allow us to gain an understanding of why the different glass components affect the regression equation in the way they do. However, the idea of these regression models was to use them in a computerised routine for composition optimisation, where the use of weight-based models presented no disadvantage compared to models based on molar percentages. An additional point to consider is that these models are only valid for the compositional range covered by the components included in developing the regression model. This raises the question whether such models are really predictive or only descriptive: while they seem to work fine for describing the composition/property relationship for the glasses included, it remains to be confirmed in each case whether they are equally useful for helping us to design and select new bioactive compositions. Another disadvantage of such relatively simple regression approaches is that they focus on one glass property per equation only. If we want to combine several properties at a time, say, bioactivity with good high-temperature processing, more sophisticated regression approaches may offer advantages. To our knowledge, however, no such studies have been performed on bioactive glasses.

Increasing amounts of data available to describe glass properties affecting glass manufacturing as well as glass performance in the final application pave the road towards improved composition optimisation. More modern approaches for optimising glass compositions make use of machine learning and artificial intelligence to design new glass compositions and even products [Mauro 2018; Venugopal et al. 2021]. So far, this approach has not been used much in the field of bioactive glasses. In one study, the dissolution behaviour of phosphate glasses for biomedical applications was described using artificial neural networks, ANN [Brauer et al. 2007]. As ANN generate black box models only, interpretation of an ANN is not necessarily easy. For this reason, Echezarreta-Lopez and Landin [2013] used a neurofuzzy logic approach, which combines the ANN adaptive learning capabilities with the fuzzy logic representation through simple rules such as IF… THEN rules. Their study, which to our knowledge constitutes the only study looking at silicate-based bioactive glasses, investigated the factors affecting bioactive glass antibacterial activity. The authors collected data from the literature, combining them in a large database which they then analysed using neurofuzzy logic. Their results show that, based on the data available, bioactive glass antibacterial activity is mainly determined by the release of alkaline metal cations from the glass into the culture medium and the concomitant increase in pH. Microbiological conditions such as culture media and time did not have a significant impact on the results, as long as they were suitable for the culture of the bacterial species under investigation.

Machine learning is a promising tool to understand, design and optimise bioactive glasses. One reason for it being used sparingly probably lies in the fact that large datasets are needed. In studies on bioactive glasses, usually relatively small sets of different compositions are investigated. This means that for meaningful analyses using machine learning tools, the results from many different studies need to be combined. Unfortunately, experimental conditions when studying bioactive glasses, especially for in vitro immersion and cell culture experiments, vary widely, which raises doubts as to how comparable the results really are. For this reason, members of Technical Committee 04—Bioglasses of the International Commission on Glass recently presented a unified method for performing acellular immersion experiments on bioactive glasses [Maçon et al. 2015]. Ideally, more standardised approaches for characterising other glass properties will be adopted by the bioactive glass community in the near future.

3. Structural analyses as a foundation for new design strategies

For a long time, detailed structural analyses were constrained by glasses’ lack of periodic, i.e., crystalline, order in their structure. Nowadays, however, we have several analytical tools available to investigate the atomic set-up of glasses. Especially advances in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy made it possible to get detailed insight into glass short-range and, to some extent medium-range, structure. A key advantage of solid-state NMR spectroscopy is that the method looks at one specific nucleus at a time (typical examples in glass research being 29Si, 31P or 11B for analysing glass networks but also 19F or 23Na), which means that even in multi-component compositions, such as those of many bioactive glasses, data interpretation can be much easier than, e.g., for vibrational spectroscopy. Combined with other structural analysis tools, including Raman and infra-red (IR) spectroscopies [Sawangboon et al. 2020] as well as X-ray and neutron diffraction experiments [Martin et al. 2012] but also computer simulation [Christie et al. 2011], we can now get insight into how the atoms in many bioactive glass systems are arranged. This allows us to establish structure/property relationships in addition to the composition/property relationships discussed above.

One of the first structural studies on bioactive glass compositions by solid-state NMR spectroscopy was performed by Lockyer et al. [1995]. Their main finding was that phosphate did not form part of a phosphosilicate network (or “backbone”) of the glass but was present as isolated orthophosphate groups. This was later confirmed by very detailed solid-state NMR spectroscopy studies using 17O and 29Si-enriched Bioglass 45S5 [Pedone et al. 2010], although few NMR spectroscopy [Fayon et al. 2013] and computer simulation studies [Tilocca and Cormack 2007] found small amounts of Si–O–P bonds.

At about the same time, Hill [1996], a polymer scientist by training, aimed to find a way to predict whether a particular glass composition would be bioactive or not, and he published his view on how bioactivity was related not only to glass composition but also structure. He noted that the degree of polymerisation of the silicate network, which he termed “network connectivity” (NC), was particularly useful in predicting the bioactivity of a given silicate or phosphosilicate glass. One should note that in Hill’s publication the calculated NC values are incorrect, most likely because, at the time of writing, Hill was unaware of Lockyer et al.]’s [1995] solid-state NMR spectroscopy study showing phosphate present in bioactive glasses as orthophosphate mostly. Hill therefore assumed that all phosphate formed part of the silicate network connected via Si–O–P bonds. Since then, NC calculations taking this into account have been described a number of times in the literature [Brauer et al. 2009; Brauer 2015; Hill and Brauer 2011].

The reasoning behind the network connectivity approach is that silicate glasses can be described as inorganic polymers, and that their properties, e.g., their thermal properties or crystallisation tendency, are determined to a large extent by the degree of network polymerisation or NC. A more disrupted silicate network with large concentrations of non-bridging oxygen atoms (NBO) caused by large modifier concentrations also facilitates water intrusion, thereby enabling the initial ion exchange process which is a requirement for ion release and apatite surface layer formation of bioactive glasses. The importance of NBO in this process was visualised impressively by computer simulations [Tilocca and Cormack 2011]. Dynamic ion release experiments [Fagerlund et al. 2013] highlighted pronounced differences between bioactive glasses and conventional silicate compositions and illustrated how glasses with higher NC (owing to higher silica content) release less ions but also release them more slowly. While it is not possible to define a clear cut-off value in NC above which ion release and bioactivity are impeded entirely, both decrease drastically as NC increases [Brauer 2015].

When performing ionic substitutions in a bioactive glass, keeping the network connectivity constant helps to maintain bioactivity. It also allows for the investigation of how substitutions impact on bioactivity without this being affected by changes in NC. This is most easily achieved by performing substitutions on an atomic (or molar) basis [O’Donnell and Hill 2010]. Based on this principle, a partially strontium-substituted version of Bioglass 45S5 was developed, which was later commercialised as StronBone™ [Jones et al. 2016; O’Donnell et al. 2010]. The necessity of maintaining a constant NC was also illustrated in studies on increasing phosphate contents in bioactive glasses in order to increase the rate of in vitro apatite surface layer formation [Hill and Brauer 2011; O’Donnell et al. 2008, 2009] and on incorporating fluoride in order to optimise bioactive glasses for dental and oral health applications [Brauer et al. 2009; Gentleman et al. 2013]. In combination [Mneimne et al. 2011], these studies resulted in the development of a bioactive glass (BioMin®) for application in dentifrices [Jones et al. 2016].

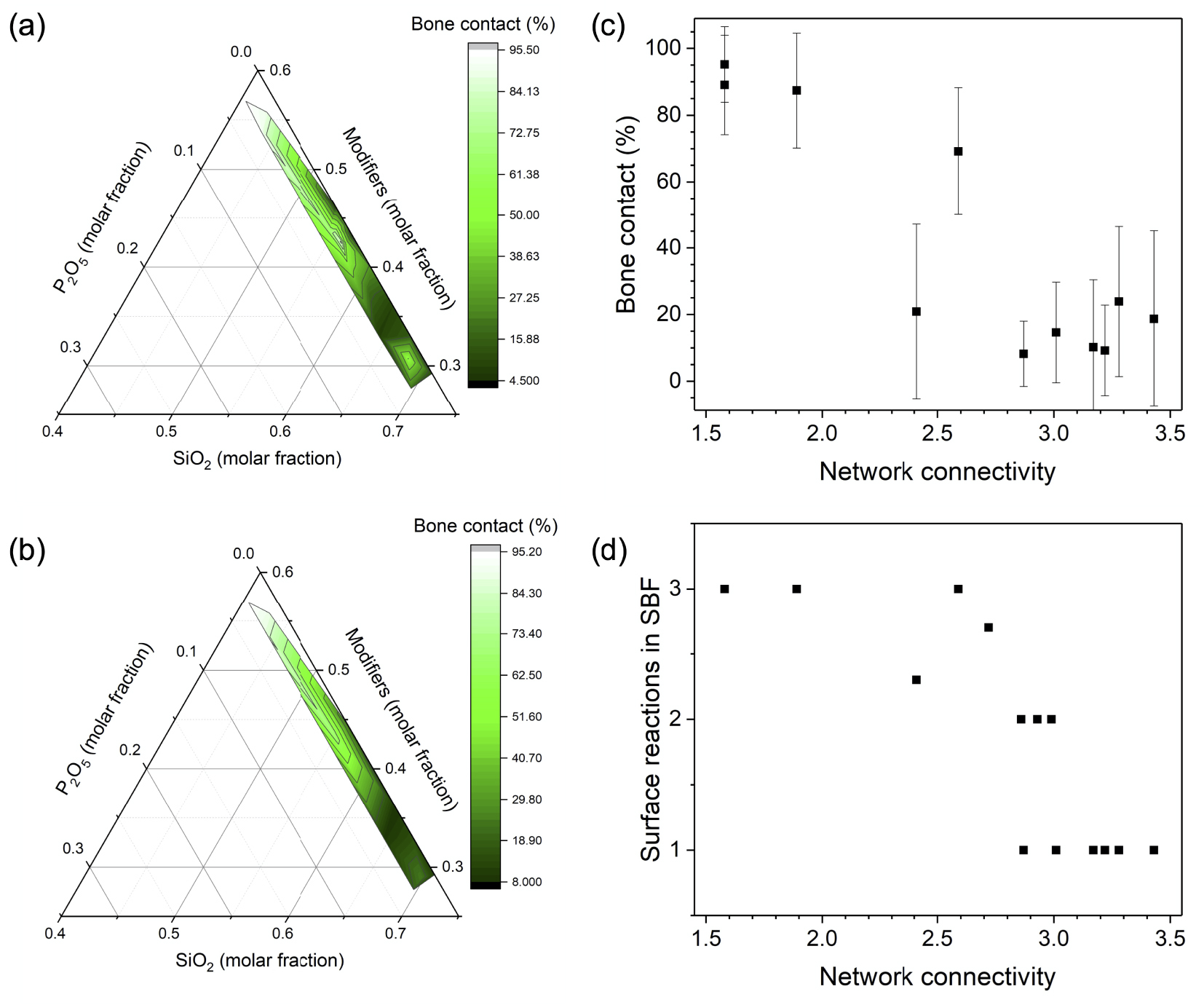

Figure 1 shows the compositional and structural dependency of in vivo bone contact of bioactive glasses in the system Na2O–K2O–MgO–CaO–B2O3–P2O5–SiO2 at 8 weeks of implantation in rabbit tibia [Brink et al. 1997]. If we look at the entire dataset (Figure 1a), we observe a trend of decreasing bone contact with increasing silica molar fraction and decreasing modifier molar fraction. Some deviation from this trend is likely to be caused by structural effects of boron present in some of the glasses, which can be present in both three- and four-fold coordination and, thus, affects the overall degree of network polymerisation. If we only look at borate-free compositions (Figure 1b), the trend is clearer. Figure 1c illustrates how in vivo bone contact decreases with NC (calculated for borate-free glasses only, as no structural information was available for the borate-containing ones). The large error bars originate from variations in the type of modifier present as well as normal variation during studies involving living systems. In Figure 1d, variation in bioactive glass surface reactions during immersion in simulated body fluid (SBF, an acellular testing solution, being similar in composition to the inorganic components of blood plasma) are shown to also correlate with glass NC [Brink 1997b]: glasses with the highest NC showed no significant surface reactions, while with decreasing NC silica gel and calcium phosphate layer formation was observed. This silica gel layer is a surface layer of ion depleted silicate, while the release of calcium and phosphate ions from the glass (together with those ions present in the testing solution, SBF, and a concomitant pH increase) cause precipitation of biomimetic crystalline apatite-like surface layers [Nommeots-Nomm et al. 2020].

(a) Ternary plot of in vivo bone contact (%) over molar composition for bioactive glasses investigated by Brink et al. [1997], (b) ternary plot of in vivo bone contact (%) over molar composition for borate-free bioactive glasses investigated by Brink et al. [1997], (c) in vivo bone contact (%) and (d) surface reactions in simulated body fluid (SBF) vs. network connectivity for borate-free bioactive glasses investigated by Brink [1997b] (1: glass surface showing no significant changes after immersion in SBF (inert glasses), 2: glass surfaces consisting of silica gel layer, 3: glass surfaces completely covered with calcium phosphates and intermediate stages).

Today, in addition to classic glass structure investigations, the topological constraint theory provides an additional tool for describing structure/property relationships in glasses and for tailoring compositions for various functional applications [Bauchy 2019; Smedskjaer et al. 2011]. The theory was inspired by the knowledge on the stability of mechanical trusses as well as Zachariasen’s work on glass structure [Phillips and Thorpe 1985; Zachariasen 1932]. Topological constraint theory reduces the glass network to nodes (the atoms present in the glass structure) which are constrained by rods (the chemical bonds between the atoms, i.e. chemical constraints). The resulting rigidity of the network allows for the prediction of various properties such as glass transition temperature or chemical durability [Mascaraque et al. 2017a, b]. Silicate glass dissolution kinetics were also investigated by combining topological constraint theory and machine learning [Liu et al. 2019], but so far no such studies seem to have been performed on bioactive glasses.

One issue with structural investigations is that results are more challenging to interpret for multicomponent glasses, and most bioactive glasses tend to contain a relatively large number of different oxides, including several glass formers (besides SiO2 typically P2O5 but often also B2O3) plus numerous modifiers. For many studies access to highly specialized equipment is required, typically available at centralised facilities only, including neutron diffraction or synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments, but also two-dimensional NMR experiments, the latter often requiring the use of isotope-enriched raw materials, which increases cost of experiments. This means that while structural studies can provide us with detailed understanding of how glass atomic structure and macroscopic properties are connected, the number of compositions currently analysed is still limited.

4. The influence of modifiers: structural aspects and therapeutic function

Bioactive glasses are known to contain relatively large concentrations of network modifiers compared to the concentrations present in conventional silicate glasses. While the amount of modifiers present affects NC, as discussed above, the type of modifiers present also determines bioactive glass properties. Calcium oxide is a typical network modifier, and calcium ions are known to influence osteoblast (bone cell) function. Sodium oxide is present in most bioactive glass compositions, but its main function is not biological or medical but to lower melting and processing temperatures. To keep these temperatures low, typically high concentrations have been used, which however are known to increase the glass crystallisation tendency.

For glasses with a constant degree of network polymerisation, variations in modifier field strength (or “charge to size ratio”) determine many of the properties. For example, the larger field strength of Ca2+ compared to Na+ (with both ions having very similar ionic radii) reduces mobility within the glass network and, thus, increases glass transition and melting temperatures and reduces the crystallisation tendency for glasses higher in calcium. This is the reason why glasses of a composition lying in the CaO–SiO2 region of the phase diagram show lower tendencies to crystallise than glasses located in the Na2O–2 CaO–SiO2 region [Arstila et al. 2008; Vedel et al. 2007]. Similarly, glasses designed for improved high temperature processing, such as 13–93 [Brink 1997a], often contain Mg2+ in addition to Ca2+ ions. Both ions have the same charge but magnesium ions are smaller than calcium ones, resulting in a larger field strength.

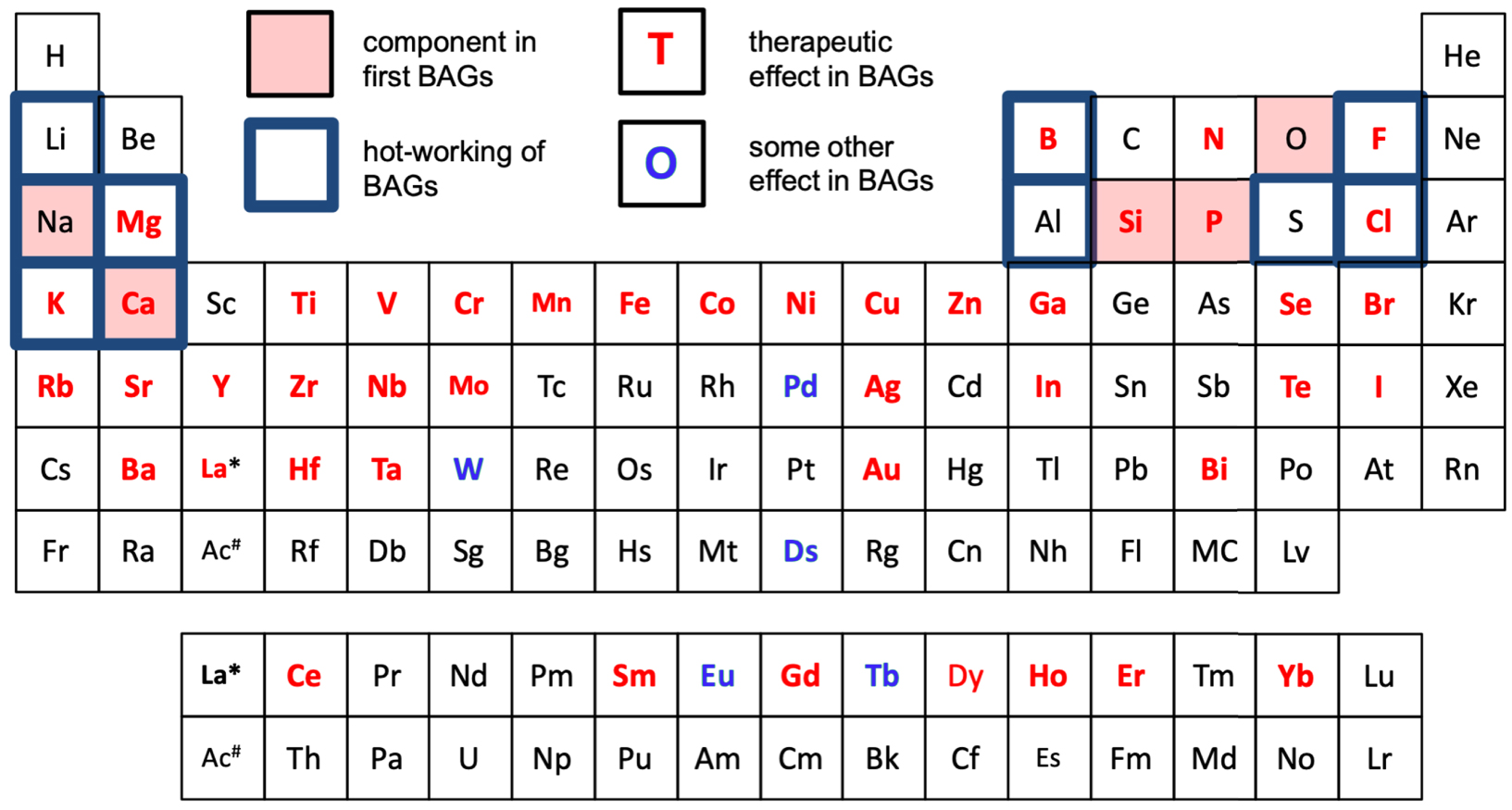

These days, however, ionic substitutions (Figure 2) in bioactive glasses focus more on broadening the glasses’ therapeutic range rather than improving basic glass properties [Hoppe et al. 2011]. The idea is that by incorporating ions possessing specific therapeutic properties, one can broaden the therapeutic spectrum of bioactive glasses. Elements added for therapeutic effects include strontium to treat osteoporosis [Gentleman et al. 2010; O’Donnell et al. 2010], cobalt to stimulate blood vessel formation [Azevedo et al. 2015], lithium to enhance hard-tissue regeneration [da Silva et al. 2017] or zinc to activate bone formation [Aina et al. 2007]. Several elements have also been added to induce antibacterial effects around the dissolving bioactive glass implant, e.g., silver [Jones et al. 2006] or zinc. Figure 2 summarises elements studied as components in bioactive glasses, either as main components forming the main glass structure or as dopants added to be released inside the body, providing specific therapeutic effects. But not only metal oxides are added to optimise bioactive glass properties. Fluoride [Mneimne et al. 2011] or chloride [Chen et al. 2015] have been incorporated in bioactive glasses for use in oral healthcare.

Periodic table summarising elements studied as components in bioactive glasses (BAGs): main elements, used to e.g. control thermal properties (blue boxes) and elements added for their specific therapeutic effect on tissue healing processes (red letters). Also, elements used as dopants for some other than a direct therapeutic effect are marked (blue letters). References used to construct the figure are not given due to the vast number of papers dealing with composition optimisation and therapeutic doping of bioactive glasses.

In ion-releasing compositions, a balance needs to be determined between obtaining a therapeutic effect while not causing any general or local toxicity issues. The released ion concentrations must be large enough to activate the desired cellular processes over a critical time period. On the other hand, concentrations that are too high may induce adverse effects. As some elements explored are classified as toxic at certain concentrations, the therapeutic window may be narrow, and the compositional optimisation for the material to be implanted into the human body is challenging. Doping with transition elements or heavy metals, for example, is against Larry Hench’s original idea of composing bioactive glasses of elements abundant in the human body, but few in vitro studies have shown promising results. Still, the actual physiological or medical use must remain at least doubtful until in vivo or clinical studies have provided reliable information on the impact of the bioactive glass composition on the desired tissue regeneration effects. So far, most clinical studies have been performed for Bioglass 45S5 and BonAlive S53P4 compositions only.

5. Conclusions

While Larry Hench often described his development of the first bioactive glass as an educated guess, we show how fundamental knowledge and understanding of glass science was key in developing and optimising bioactive glass compositions and furthering their clinical use. Various tools have been employed over the years, including regression modelling, structural analyses and machine learning. Composition optimisation to identify glasses suitable as implant materials requires a cross-disciplinary understanding of both glass science and biomedicine. In addition, transferring a promising composition to clinical applications requires a thorough knowledge of the regulatory work needed. Nevertheless, tools for glass property optimisation are an important first step towards new biomaterials, and they may even offer feasible means to minimise experimental work and animal studies.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0