1 Introduction

Variations in the CO2 and O2 content of the atmosphere over Phanerozoic time (past 550 Ma), and the geological/biological factors affecting them, have been a topic of major interest only during the past few decades [5,7,11,12,17]. This is unfortunate because the fundamental principles were laid down as early as 1845 by the French chemist J.-J. Ebelmen [10], but, unfortunately this work was subsequently forgotten. Ebelmen summarized both in words (Table 1), and partly in the new, at that time, nomenclature of chemical symbols and reactions, the following global reactions (which should bear his name):

Processes that control atmospheric CO2 and O2. These are the exact words of the original table of J.-J. Ebelmen [10] (p. 64)

Mécanismes contrôlant les valeurs de CO2 et O2 atmosphériques. Ce sont les termes exacts du tableau de J.-J. Ebelmen [10] (p. 64)

| 1. Causes qui tendent à augmenter la proportion d'acide carbonique contenue dans l'air | |

| a. Sans diminuer la proportion d'oxygène libre | L'émission des gaz en rapport avec les orifices volcaniques |

| b. En diminuant la proportion d'oxygène | 1. La destruction des matières organiques contenues dans les terrains stratifiés (houilles, lignites, bitumes) |

| 2. La décomposition des pyrites de fer et des fers spathiques | |

| 2. Causes qui tendent à diminuer la proportion d'acide carbonique | |

| a. En mettant de l'oxygène en liberté | 1. La formation des pyrites de fer |

| 2. La formation des combustibles minéraux et la conservation de tous les débris organiques | |

| b. Avec ou sans absorption d'oxygène | 1. La décomposition des silicates des roches ignées |

| 3. Causes qui tendent à augmenter la proportion d'oxygène contenue dans l'air | |

| a. Sans diminuer la proportion d'acide carbonique | (aucun) |

| b. En diminuant la proportion d'acide carbonique | 1. La formation des combustibles minéraux |

| 2. La formation des pyrites de fer | |

| 4. Causes qui produisent une diminution de l'oxygène contenu dans l'air | |

| a. Avec formation d'acide carbonique | 1. La destruction des matières organiques contenues dans les terrains |

| 2. La décomposition des pyrites de fer et des fers spathiques | |

| b. Avec absorption d'acide carbonique | 1. La décomposition des silicates de roches ignées |

They are:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Reaction (3) illustrates processes affecting both CO2 and O2. Going from left to right, it represents net photosynthesis (photosynthesis minus respiration) as represented by the burial of organic matter (CH2O) in sediments. Going from right to left it represents two processes: (i) the oxidation of old sedimentary organic matter subjected to weathering on the continents and (ii) the sum of several reactions involving the thermal breakdown of organic matter via diagenesis, metamorphism and magmatism with the resulting reduced carbon-containing compounds released to the Earth's surface where they are oxidized to CO2 by atmospheric or oceanic O2.

Reaction (4) affects only O2, and its exact stoichiometry was originally deduced by Ebelmen [10]. Going from right to left it represents the oxidation of pyrite during weathering on the continents (reduced organic sulfur is lumped here with pyrite for simplification) and the sum of thermal pyrite decomposition and the oxidation of resulting reduced sulfur-containing gases produced by metamorphism and magmatism. Going from left to right, reaction (2) is the sum of several reactions. They are (i) photosynthesis and initial burial of organic matter (reaction (1)), (ii) early diagenetic bacterial sulfate reduction and the production of H2S, with organic matter serving as the reducing agent and (iii) precipitation of pyrite via the reaction of H2S with Fe2O3.

It is the purpose of the present paper to show how the rise and spread of plants in the mid-Paleozoic led to changes in atmospheric CO2 and O2 as they affected these global chemical reactions.

2 Plants and atmospheric carbon dioxide

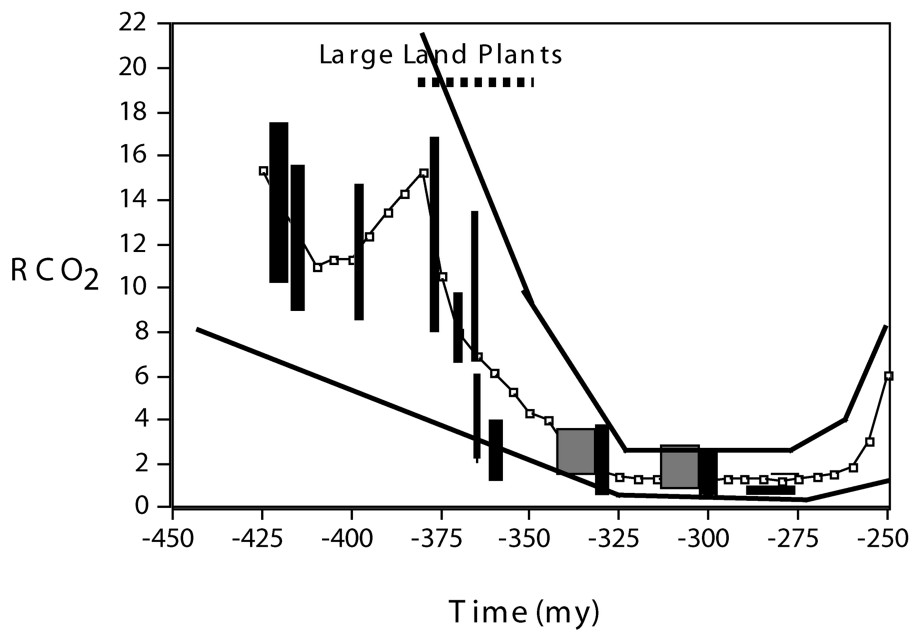

Large vascular plants, with deep and extensive rooting systems, arose and spread over the continents starting about 380 Ma during the Devonian Period [18]. Theoretical carbon cycle modeling [4] indicates that effects on atmospheric composition of the occupation of the land by large plants were twofold. First, a drop in CO2 was brought about by plant-accelerated weathering of CaMg silicate minerals (reactions (1) and (2) above). The model calculated drop is based on studies of the quantitative effect of trees on rates of modern weathering of CaMg silicate minerals [13] and results for CO2 agree with those based on the carbon isotopic composition of paleosols and the stomatal density of fossil leaves (Fig. 1). The lower CO2 levels helped to bring about greenhouse cooling and the deceleration of weathering, counterbalancing the acceleration of weathering by plants resulting in the stabilization of CO2 at lower levels. The lowered levels of CO2 are believed to have helped to initiate the Permo-Carboniferous glaciation, the longest and most extensive glaciation of the past 550 million years [8].

Plot of Paleozoic RCO2 vs. time based on GEOCARB III modeling [4] for a four-fold effect [13] of plants on weathering rate (line connecting dots). RCO2 represents the ratio of the mass of CO2 in the atmosphere at some past time to that for the pre-industrial present (280 ppmv). Upper and lower lines represent estimated range of GEOCARB error. The superimposed vertical bars and larger squares represent independent estimates of paleo-CO2 via the carbonate paleosol and stomatal ratio methods respectively (see [15] for a discussion and evaluation of these other methods).

Diagramme représentant le RCO2 paléozoı̈que en fonction du temps sur la base de la modélisation GEOCARB III [4] d'un effet quadruple [13] des plantes sur le taux d'altération (ligne de points reliés). RCO2 représente le rapport de la masse de CO2 dans l'atmosphère à un moment passé donné à celle observée pour le présent préindustriel (280 ppmv). Les lignes du haut et du bas représentent la marge d'erreur estimée de GEOCARB. Les barres verticales et les carrés plus larges représentent les estimations indépendantes du paléo-CO2 selon les méthodes du rapport au paléosol carbonaté et aux stomates, respectivement (voir [15] pour une discussion et une évaluation de ces autres méthodes).

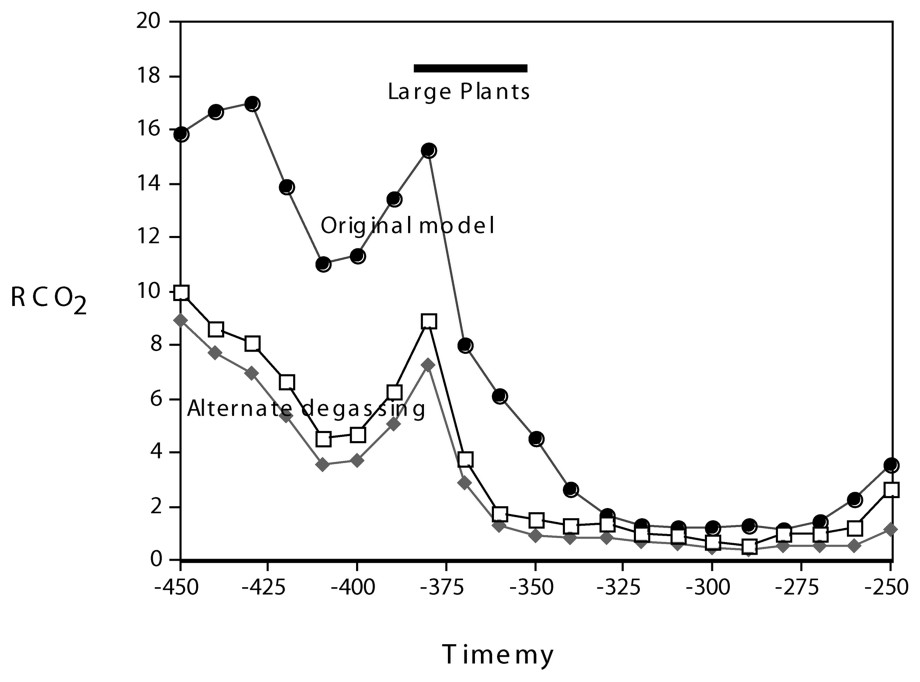

An alternative approach to carbon cycle modeling [16] places emphasis on changes in volcanic and metamorphic degassing of CO2 to the atmosphere (reaction (1) going from right to left) due to changes in the carbonate content of sediments undergoing subduction. To consider this effect on Paleozoic CO2, our carbon cycle modeling has been revised to include changes over time in the distribution of carbonate burial between shallow platform seas and the deep ocean [14] with the assumption that only carbonate deposited in deep sea sediments is later subjected to thermal degassing with complete conversion to atmospheric CO2. Results are shown in Fig. 2 and show that the large plant-weathering-induced Devonian drop in CO2, even under these extreme assumptions, is not qualitatively changed by the alternative formulation of global CO2 degassing.

Plot of RCO2 vs. time for the same time span of Fig. 1 calculated by the alternate formulation of global degassing that assumes changes with time in the CaCO3 content of Paleozoic subducting deep-sea sediments.

Représentation de RCO2 en fonction du temps pour le même éventail de temps que celui apparaissant sur la Fig. 1, calculé par une autre formulation de dégazage global qui prend en compte les changements avec le temps de la teneur en CaCO3 des sédiments paléozoı̈ques profonds subductants.

The other effect of the rise of woody plants such as trees was the production of large amounts of microbially resistant organic compounds such as lignin. Because of a lack of decomposition during deposition and early diagenesis, the burial of such non-biodegradable organic matter led to the increased removal, globally, of organic carbon into sediments. This increased carbon burial brought about further CO2 removal (reaction (3)) resulting in the low levels of CO2 at 325–275 Ma shown in Fig. 1. Burial of the ligniferous organic matter could have been both on land, giving rise to the great coal deposits of this time, or in the oceans after transport there via rivers. Overall global organic burial was increased because the new source of terrestrially derived carbon was added to the already existing source, the remains of marine organisms.

3 Plants and atmospheric oxygen

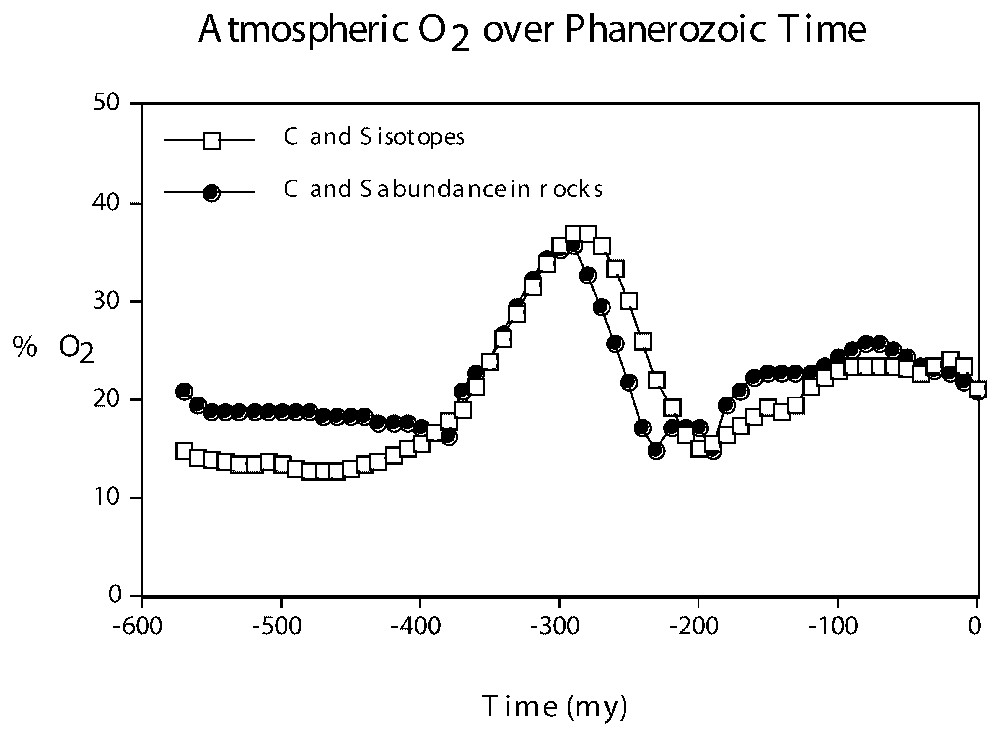

The enhanced burial of organic matter resulted also in an accelerated input of photosynthetically-produced oxygen to the atmosphere (reaction (3)), which is believed to have led to increased levels of atmospheric O2. High levels of Permo-Carboniferous O2 have been deduced by computer models of the long term carbon and sulfur cycles, based on the abundance of organic C and pyrite S in sedimentary rocks [3], and on the carbon and sulfur isotopic composition of seawater over time [2]. Results of the modeling are shown in Fig. 3.

Plots of %O2 in the atmosphere vs. time based on modeling calculations of the abundance of organic carbon and pyrite sulfur in sedimentary rocks [3] and on the carbon and sulfur isotopic composition of the oceans [2] over Phanerozoic time.

Représentation de O2 en fonction du temps sur la base de calculs modélisant l'abondance du carbone organique et du soufre des pyrites [3] et de la composition isotopique du carbone et du soufre des océans [2] pendant le Phanérozoı̈que.

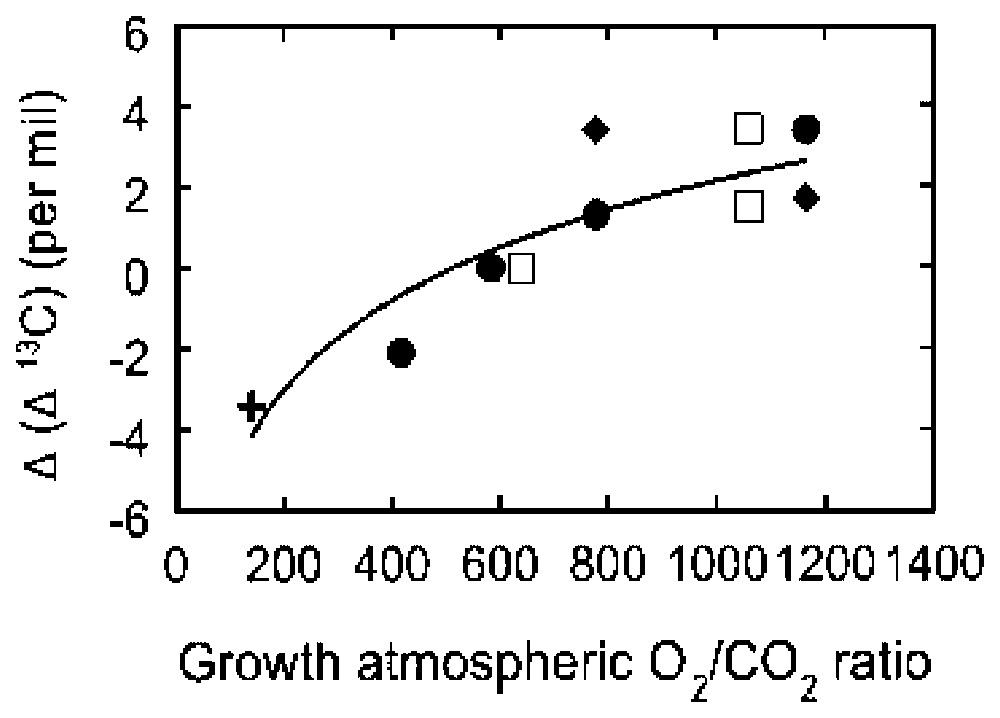

The calculated high levels of Permo-Carboniferous atmospheric O2 are supported by independent laboratory experiments. The presence of giant insects, especially dragonflies, only during this time period has been explained in terms of elevated O2 levels [9]. To verify this idea, recent preliminary laboratory experiments by R. Dudley have actually demonstrated an increase in mean body weight, between successive generations, during exposure of populations of Drosophila to elevated partial pressures of O2 [6]. The model-based calculations also predict that the fractionation of carbon isotopes during photosynthesis should increase with increasing atmospheric O2 concentration. This idea is verified by increases in the fractionation of carbon isotopes by Permo-Carboniferous fossil plants and by laboratory growth experiments with modern plants [1] (Fig. 4).

Plot of Δ(δ13C) of vascular land plants grown under varying O2/CO2. Δ(δ13C) is the difference in carbon isotope fractionation during photosynthesis, δ13C, from the fractionation for present-day conditions (21% O2, 0.036% CO2). After [1].

Représentation de Δ(δ13C) de plantes vasculaires terrestres dont la croissance s'est déroulée sous des rapports O2/CO2 variés. Δ(δ13C) représente la différence de fractionnement de l'isotope du carbone pendant la photosynthèse, δ13C, à partir du fractionnement dans les conditions actuelles (21% O2, 0,036% CO2). D'après [1].

Acknowledgements

Research supported by DOE Grant DE-FG02–01ER15173 and NSF Grant EAR 0104797. Denis Cohen is thanked for help in the translation into French.