1 Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently reported that around 4 million people die each year as a result of outdoor air pollution exposure (WHO, 2014). Spaceborne remote sensing instruments probing the troposphere are now able to follow pollution patterns at global, regional and local scales. Rapid changes in air composition can be measured, and episodic events such as large fires, volcanic plumes or pollution peaks over urban areas can be tracked. The IASI mission is now recognized as a key element to monitor and forecast pollution from space.

Back in the late 1980s, French scientists2 proposed the concept of a satellite mission based on a hyperspectral infrared sensor with the aim to remotely sound the troposphere and provide information required for both operational weather forecasting and atmospheric chemistry monitoring (CNES, 1989). The measurement device would exploit the thermal infrared radiation emitted by the Earth's surface, and record the radiance signal altered when passing through the atmosphere and interacting with infrared absorbing molecules. From the measured atmospheric spectra, vertical profiles or total columns could be derived for temperature, water vapor, ozone, and for some other gases playing an important role for climate or atmospheric chemistry. The high spectral resolution would allow disentangling the individual spectral lines, which are specific to each infrared absorbing constituent. Information on coarse particles would also be available to some extent, using their broadband absorption in the atmospheric window.

In the 1990s, the “Centre national d’études spatiales” (CNES) designed the Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI; Cayla, 1993), and the Eumetsat agency selected it to be part of the space segment of its Eumetsat Polar System program. Three instruments based on a Fourier Transform Spectrometer were built by the Thales industry to be embarked on the polar orbiting MetOp suite of satellites (Blumstein et al., 2004). MetOp-A was launched at the end of 2006 and is still in operation, followed by MetOp-B launched at the end of 2012. The last flight model will fly on MetOp-C, now scheduled for launch at the end of 2018.

This paper highlights some of IASI's accomplishments after 8 years of operational observations, in particular for the study of reactive gases playing important roles in atmospheric chemistry, pollution buildup and transport.

2 The IASI sounding mission

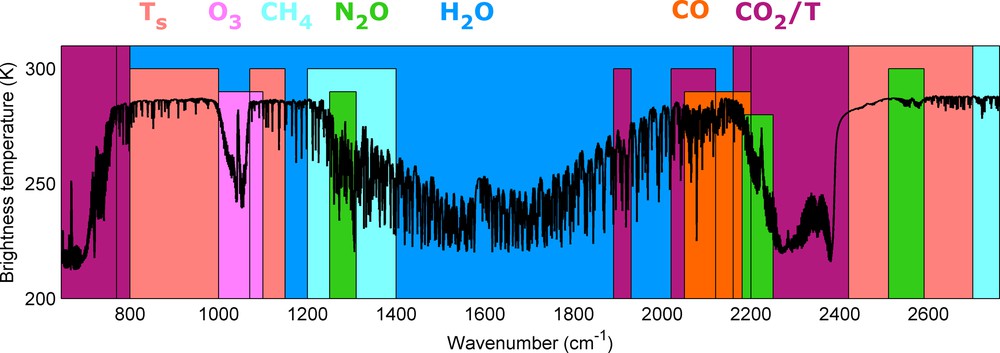

The IASI instrument measures the upwelling radiances in the thermal infrared spectral range extending from 645 to 2760 cm−1 (3.6 to 15.5 μm), with high radiometric quality, with 0.5 cm−1 spectral resolution, apodized. Apodizing functions are used in Fourier transform spectroscopy to reduce the magnitude of the sidelobes in the instrumental line shape, which are a direct result of the finite maximum optical path difference in the measured interferogram. Each observation represents 8460 radiance channels, from which information on the surface properties and the atmospheric composition and variables can be derived using ad hoc retrieval algorithms (Clerbaux et al., 2009; Hilton et al., 2012). A representative atmospheric spectrum is plotted on Fig. 1, with the absorption features associated with the ro-vibrational spectroscopic lines of the main absorbers identified. A total of 120 views are collected over a swath of ∼ 2200 km using a stare-and-stay mode of 30 arrays of 4 individual elliptical pixels, each of which is 12 km diameter at nadir (increasing at the larger viewing angles). The MetOp satellites are flying at about 817 km on a polar sun synchronous orbit, with around 14 orbits per day, MetOp-A and MetOp-B being half an orbit apart (see Fig. 2, upper panel). The local overpass time for the morning and evening orbits is around 9:30 (see Fig. 2, bottom panel). More than 1.2 million spectra per day are collected by each IASI instrument, from which a significant part is affected by the presence of clouds in the field of view and therefore discarded for the atmospheric composition retrievals. Every orbit batch of data is made available by the Eumetsat dissemination system, so that a near real time processing of the data is possible.

(Color online.) Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI) atmospheric spectrum (in brightness temperature units) with the location of the absorption features for the main absorbing species. Temperature profiles are retrieved using the CO2 absorption bands, whereas surface temperature (Ts) and aerosols can be observed in the atmospheric windows (plotted in peach color).

(Color online.) Top, A: MetOp-A and MetOp-B tandem operation on a polar orbit. A full Earth coverage is ensured each morning and each evening, with more frequent overpasses at higher latitudes. Orbits were plotted using the Ixion software (Capderou, 2005). Bottom, B: local time for the morning overpass (IASI-A) for one day of observation (July 1, 2011). Note that the missing data within the orbit swath correspond to cloud-contaminated data that are filtered out before the trace gas retrieval processing. Masquer

(Color online.) Top, A: MetOp-A and MetOp-B tandem operation on a polar orbit. A full Earth coverage is ensured each morning and each evening, with more frequent overpasses at higher latitudes. Orbits were plotted using the Ixion software (Capderou, ... Lire la suite

3 Observing reactive gases from space

Aside from water vapor (H2O) and the long-lived climate gases [carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O)] providing the main absorptions features observable in this spectral range (see Fig. 1) and not discussed hereafter, it was foreseen that atmospheric abundances could be obtained for some reactive species such as carbon monoxide (CO), ozone (O3) and nitric acid (HNO3) (IASI Science Plan, 1998). Before the launch of the mission, trace gas retrieval tools were developed by our group, using simulated radiance data obtained from radiative transfer calculations along with atmospheric chemistry model simulations (Clerbaux et al., 1998; Hadji-Lazaro et al., 1999, Turquety et al., 2004). Luckily, a somewhat similar thermal infrared nadir looking sounder – the Interferometric Monitor for Greenhouse Gases (IMG) – launched in 1996 onboard the Japanese ADEOS platforms (Kobayashi et al., 1999), provided a few weeks of real data before the platform stopped operating due to a failure of its solar panels. Using this dataset, the processing tools to derive atmospheric concentrations from atmospheric spectra could be tested and improved (Barret et al., 2005; Clerbaux et al., 1999, 2001, 2002, 2003; Coheur et al., 2003, 2005; Hadji-Lazaro et al., 2001; Herbin et al., 2007; Turquety et al., 2002; Wespes et al., 2007).

After a long wait, the first IASI was finally launched on MetOp-A in October 2006. Daily maps are now routinely generated for O3 (Boynard et al., 2009), CO (George et al., 2009) and HNO3 (Wespes et al., 2009). The data are processed in operational mode, “on the fly”, using a dedicated algorithm optimized to process hundreds thousands of data per day (Hurtmans et al., 2012). Fig. 3 presents averages maps for CO and ozone, along with their associated standard deviation. It can be seen that strong regional variability occurs, with larger abundances generally found in the Northern Hemisphere (with a maximum above China), as well as over Equatorial Africa. The standard deviation indicates where the maximum variability lies. A more complete analysis of seasonal maps will be provided in Section 3.1 for CO, and 3.2 for O3.

(Color online.) Daytime composite images for seven years (2008–2014) of IASI measurements. High values are in red. Upper panels: CO total columns in 1018 molecules/cm2 units (left) and the associated standard deviation (right). Bottom panels: O3 [0–6] km column and variability in Dobson Unit (DU), representative of tropospheric ozone concentration. Note that a grey mask has been put over desert regions for the ozone plots, because of emissivity issues in this spectral region.

Not long after the launch of the mission, it turned out that much more species were measurable than anticipated, owing to the low radiometric noise combined with the exceptional horizontal coverage. We discovered that a series of short lived gases and the less stable isotopic forms of water vapor could be detected, with absorption signatures sometimes just above the instrumental noise levels (Clarisse et al., 2011a; Coheur et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2011). Scientific studies using this wealth of data now include:

- • global/regional atmospheric composition and pollution analysis (Barret et al., 2011; Bauduin et al., 2014; Boynard et al., 2014; Clerbaux et al., 2010; Cooper et al., 2014; Cuesta et al., 2013; Doche et al., 2014; Dufour et al., 2010; Eremenko et al., 2008; Foret et al., 2014; Gazeaux et al., 2013; Pommier et al., 2010, 2012; Safieddine et al., 2013, 2014; Thonat et al., 2012; Wespes et al., 2012);

- • volcanic plumes early detection and monitoring (Boichu et al., 2013, 2014; Clerbaux et al., 2011; Clarisse et al., 2008, 2010c, 2011c, 2012, 2014; Karagulian et al., 2010; Sears et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2012);

- • fire plumes observation and composition (Coheur et al., 2009; Duflot et al., 2013; Huijnen et al., 2012; Krol et al., 2013; R’Honi et al., 2013; Turquety et al., 2009);

- • atmospheric budgets of organic species emitted in large parts from vegetation (Razavi et al., 2011; Stavrakou et al., 2011, 2012; Wells et al., 2012);

- • atmospheric circulation and hydrological cycle studies through the distribution of isotopic water molecules (Clarisse et al., 2011b; Herbin et al., 2009; Hoffmann et al., 2014; Lacour et al., 2012, 2015; Pommier et al., 2014; Schneider and Hase, 2011; Wiegele et al., 2014);

- • ozone hole monitoring (Scannell et al., 2012; Wespes et al., 2012);

- • identification of coarse particles (Capelle et al., 2014; Clarisse et al., 2010a, 2013; Peyridieu et al., 2013; Vandenbussche et al., 2013);

- • ammonia (NH3) sources monitoring (Clarisse et al., 2009, 2010b; Ginoux et al., 2012; Heald et al., 2012; Van Damme et al., 2014a,b; Whitburn et al., 2015);

- • long-term trends (Worden et al., 2013).

Table 1 provides a summary list of all molecules and particles that have been observed so far in the IASI spectra. Some species can be measured everywhere, some are only observed over selected places and time periods. For the stronger absorbers (CO, O3 and HNO3) coarse vertical profiles can be derived by converting the radiances to concentration products. This takes place in an optimal estimation framework, with diagnostic information to estimate the sensitivity of the observation at different altitudes and provide associated errors (Hurtmans et al., 2012). For weak absorbers only total column contents can be derived. Of particular interest among this observable list is ammonia (NH3), a major pollutant and a precursor of particles formation that was never thought to be observable from space before the launch of IASI. Section 3.3 will provide more information on the “discovery” of this molecule. It is worth noting that thermal infrared remote sensors have generally low capability to sound down to the surface, unless there is a significant difference between the temperature at ground level and just above (hereafter called ‘thermal contrast’).

Reactive gases and particles (in italic) observed with the IASI mission, along with the information services that use IASI data.

| Scientific goal | Measured species | Information services |

| Atmospheric composition | ||

| Ozone hole (stratosphere) | Ozone (O3) Nitric acid (HNO3) |

ESA Climate change Initiative for assessing the fate of atmospheric ozone and better understand its link with anthropogenic activities: CCI-O3, http://www.esa-ozone-cci.org/ |

| Pollutants (troposphere) | Carbon monoxide (CO) Ammonia (NH3) Ozone (O3) Nitric acid (HNO3) Sulfur dioxide (SO2) Ammonium sulfate |

CO forecast provided by the pre-operational Copernicus Atmosphere Service (MACC project): https://www.gmes-atmosphere.eu/ |

| Volcanic events | ||

| Volcanic plumes | Sulfur dioxide (SO2) Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) Sulfuric acid (H2SO4) Ash |

SO2 and ash maps provided to civil aviation through volcanic alerts: http://sacs.aeronomie.be/ |

| Biomass | ||

| Biomass burning | CO, O3, HCN, methanol (CH3OH), formic acid (HCOOH), ethane (C2H4), acetylene (C2H2), hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and PAN (C2H3O5N) | |

| Biogenic activity | Methanol, formic acid | |

| Atmospheric circulation and thermodynamics | ||

| Gravity waves | T (CO2) | |

| Evaporation/condensation | HDO/H2O | |

| Dust transport | Dust (AOD) | ESA Climate change Initiative for producing global aerosol ECV products: aerosol_cci, http://www.esa-aerosol-cci.org/ |

Finally, both the availability of the data in near real time and the long-term plans for the mission have triggered the integration of the data into operational applications, to feed information services such as (also see Table 1):

- • systematic forecasts of CO distribution for a few days ahead over Europe (Inness et al., 2013; Klonecki et al., 2012);

- • alerts for early detection of volcanic eruption for aircraft routing (Brenot et al., 2014; Theys et al., 2013);

- • long-term robust global records of essential climate variables (ECVs) for ozone and dust.

The following section illustrates the IASI observation capabilities and downstream applications for the atmospheric sciences for three important pollutants: carbon monoxide, ozone and ammonia.

3.1 Carbon monoxide measurements

CO is a combustion-related pollutant that is mainly emitted by motor vehicle traffic, heating/cooking systems, industrial activities, and biomass burning. With a lifetime of a few weeks, it can be transported over long distances. It is an excellent tracer of pollution, indicative of anthropogenic emissions, biomass burning and atmospheric circulation patterns. It is also a key atmospheric species as it regulates the oxidizing capacity of the troposphere through its destruction cycle involving the hydroxyl radical (OH), and as it is an ozone and carbon dioxide precursor.

From the numerous IASI observations, CO maps can be derived each morning and each evening, both over land and sea. When averaging over longer time periods, observational gaps due to the presence of clouds disappear. Fig. 3 shows the CO global distribution averaged over the period [2008–2014]. It can be seen that background concentrations are higher in the Northern Hemisphere as most of the pollution is associated with urban activity, with persistent elevated levels above China transported by wind towards the west coasts of USA. In the Tropics and Southern Hemisphere, most of the CO is emitted where biomass burning linked to agricultural practices occurs. From the standard deviation maps, we see that the annual variability is mostly associated with the larges fires observed in Africa, South America, Indonesia, and Indochina that vary in intensity from year-to-year.

Fig. 4 illustrates both the seasonal variability and the vertical sensitivity for the CO maps derived from IASI observations. Sunlight triggers OH production and so the chemical destruction of CO is more efficient during the summer months in the Northern Hemisphere, leading to lower concentrations in October than in April. Conversely, as the chemistry is less active during the winter months when insolation decreases, CO accumulates and concentrations peak in early spring. Fire activity in the Tropics follows the seasonal shift in the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone, moving from South Western Africa in April to South Central Africa in October. Due to long-range transport, high CO concentrations are also observed over the Northern Pacific and Atlantic oceans. The altitude of peak sensitivity for the bottom layer of retrieved CO ranges between around 2 to around 10 km, as can be seen on Fig. 4 (right plots), with most of the information coming from the mid troposphere. This implies that the instrument is mostly sensitive to uplifted and horizontally transported CO, whereas it can miss local pollution events if these are confined near the ground. Interestingly, as pollution peaks are often associated with a temperature inversion in the atmospheric boundary layer (and hence significant thermal contrast), detection at surface level is possible in these cases (see e.g. Boynard et al., 2014).

(Color online.) Daytime composite images for CO as measured by IASI in April (upper plots) and October 2013 (bottom plots). The left plots represent CO as retrieved near the surface in parties per billion volume units (ppbv), the right plots provide an indication of the altitude where most of the instrument sensitivity originates from.

CO emission inventories still present large uncertainties. These emissions can be constrained by data assimilation (Inness et al., 2013) and source inversion methods (Fortems-Cheiney et al., 2009), and IASI's excellent horizontal coverage proved to be very valuable in that regard.

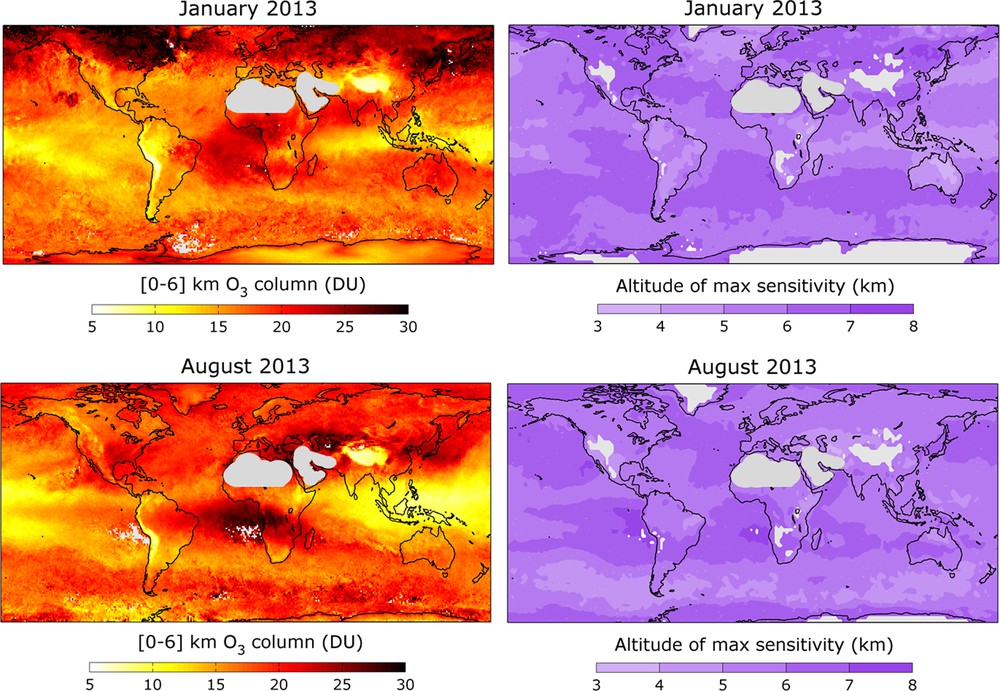

3.2 Tropospheric ozone measurements

Breathing ozone can cause a variety of health problems. The sources of O3 in the troposphere are either downward transport from the stratosphere or local chemical production within the troposphere. In urban areas, ozone is formed through sunlight-initiated oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the presence of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and CO. Urban population is often exposed to O3 levels exceeding WHO air quality guideline values. Although in Europe emissions of the main ozone precursors have significantly decreased over the past two decades, the levels of ozone have not levelled-off and ozone-related peaks are often encountered in summer.

Since most of the O3 resides in the stratosphere, the remote observation of tropospheric ozone with IASI remains tricky as absorption/emission contributions from both the stratospheric and tropospheric ozone are mixed in the spectra. Fig. 3 (bottom) illustrates the ozone observations averaged during the [2008–2014] period, integrated between the surface and 6 km altitude. In the Northern Hemisphere, the ozone budget can be explained by stratospheric intrusions (mostly at high latitudes), combined with local production over polluted continental areas and transport of O3 and its precursors (mostly at mid-latitudes). The O3 minimum over the tropical Pacific is due to the photochemical destruction by UV light and no source of ozone precursors. Tropical Atlantic O3 distribution between Central Africa and South America is governed by biomass burning and the subsequent transport of O3 and its precursors across the Atlantic. Moreover, and in particular over the South Atlantic, lighting (as a source of NOx) is shown to account for 30% of the O3 burden (Sauvage et al., 2007). The year-to-year variability is mostly driven by meteorological conditions.

Fig. 5 illustrates the ozone seasonal distributions for two representative months: January and August 2013. In general, the tropospheric O3 observed in mid and high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere are always larger than those in the Southern Hemisphere. At high latitudes in January elevated values are due to the integration of stratospheric air into the [0–6] km column as the tropopause height is low at this time of the year, and stratospheric intrusions are also bringing ozone-rich air from above. Note that the same effect is not recorded in austral winter/spring due to the ozone depletion in the Southern Hemisphere and to the Brewer-Dobson circulation that transports more O3 to the Arctic. In August, high values are measured in the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere due to the increase in photochemical activity, in particular over East Asia, and eastern/southern Europe. Important summertime O3 maxima are detected every year in the Mediterranean region (Doche et al., 2014; Safieddine et al., 2014). The tropospheric O3 product from IASI is mainly representative of O3 in the mid to upper troposphere (see Fig. 5, right plots), with some seasonal variability. This allows the study of the transport processes in these atmospheric levels using the wind patterns. Like CO, an increased sensitivity near the ground is only possible when there is a significant thermal contrast.

(Color online.) Daytime composite images for tropospheric ozone as measured by IASI in January (upper plots) and August 2013 (bottom plots). The left plots represent ozone partial columns integrated between 0 and 6 km in Dobson Units, the right plots provide an indication of the altitude where most of the instrument sensitivity originates from. Note that a grey mask has been put over desert regions, because emissivity issues affect the observation.

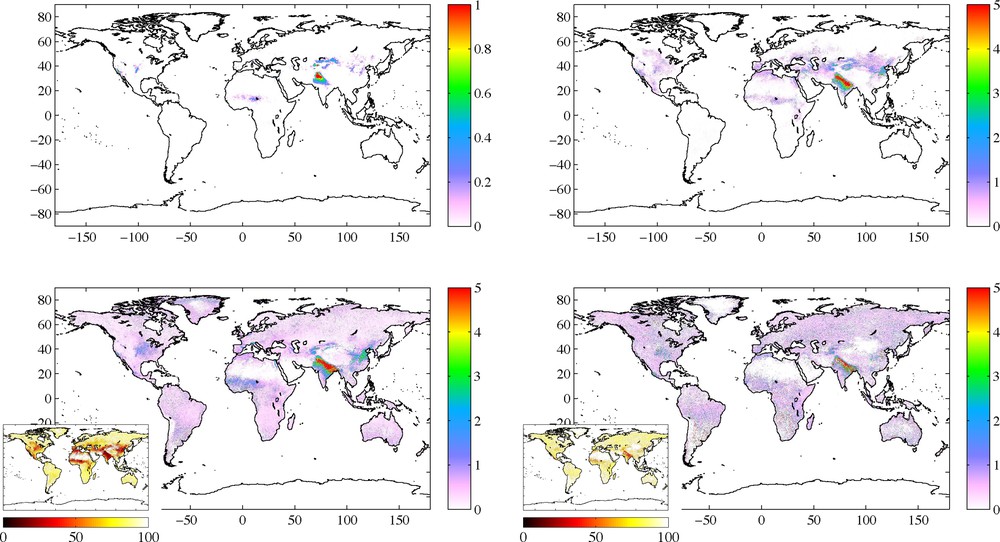

3.3 Ammonia measurements

Ammonia is a pollutant that contributes to the formation of airborne particles harmful to human health, as well as other environmental effects such as acidification of terrestrial ecosystems and loss of biodiversity. It comes from many sources (including fires), but the bulk is a result of livestock and agricultural activities through the use of nitrogen fertilizer. As emissions are strongly influenced by temperature, a concern for the future is that ammonia loading increases with hotter climate. There are still large uncertainties in the magnitude of its emissions as there is very little data available on the global scale. The measurement is difficult, local data are scarce and limited, as the gas has a short atmospheric lifetime, of a few hours to a few days.

The first detection of ammonia by IASI came about nearly by accident. It occurred when studying the composition of the plumes following the large fires that devastated thousands of square kilometers in Greece during August 2007 (Coheur et al., 2009). Interestingly, this compound is optically active in the atmospheric windows which extents from ∼ 800 to ∼ 1200 cm-1 (see Fig. 1) where no other gases absorb, and owing to the very good radiometric performances of IASI, the detection was shown to be possible. By averaging over longer time periods to increase the signal over the background noise, emission hotspots could be identified at middle and low latitudes across the globe (Clarisse et al., 2009). A major effort to develop specific processing tools adapted to weak absorbers was undertaken, leading to systematic day and night observations of ammonia. Fig. 6 illustrates the evolution of the retrieval tools in three steps: the first global map was based on the use of the brightness temperature difference between one NH3-sensitive channel along with two window channels free from absorption (see Fig. 6, upper left plot), by accumulating data over several months to compensate for weak signal. The map revealed sources that had been previously unknown, and it showed high ammonia-concentration regions in South Asia (mainly in northern India), Europe, and California. In a next step, the retrieval method was improved by extending the spectral range used, and a similar method to the one developed for CO and ozone retrievals, based on optimal interpolation, was adapted for NH3 retrievals (Clarisse et al., 2010b). Although it provided better results for large emission sources (see Fig. 6, upper right plot), the daily detection of weaker sources was still difficult. More recently, an improved method for the processing of IASI radiance to derive NH3 columns was developed (see Fig. 6, bottom plots). It exploits the hyperspectral character of the instrument by using an extended spectral range where NH3 is absorbing. It uses look-up tables built from forward radiative transfer model simulations (Van Damme et al., 2014a) to derive NH3 column abundances during daytime and nighttime, over land and over sea, without large computational resources. The retrieval also includes error characterization of the retrieved columns, a quantity directly linked to thermal contrast.

(Color online.) Composite images for NH3 as measured by IASI in June 2009. It shows the evolution of the retrieval methods developed to estimate NH3 total column (×1016 molecules/cm2) from the IASI radiance observations. Upper plot, left: using the early stage brightness temperature difference method (Clarisse et al., 2009); upper plot, right: using an adapted optimal estimation method (Clarisse et al., 2010b); bottom plots, left and right: using the hyperspectral range index method (Van Damme et al., 2014a) for daytime and nighttime observations, along with the corresponding error distributions (%, horizontal color bar). Masquer

(Color online.) Composite images for NH3 as measured by IASI in June 2009. It shows the evolution of the retrieval methods developed to estimate NH3 total column (×1016 molecules/cm2) from the IASI radiance observations. Upper plot, left: using the early stage ... Lire la suite

4 Discussion and future directions

Air quality has become a major concern, and as a result, an important area of research has emerged during the last decade to quantify the emissions of pollutants, to model the chemical and physical transformation leading to the production of secondary pollutants, and to study the transport pathways for the spread of pollution. Remote sensing observation from satellite is increasingly viewed as a means to measure pollution, to monitor atmospheric changes and to control the implementation of environmental policies.

The thermal infrared IASI mission has provided an uninterrupted record of atmospheric spectra since 2007, from which several key atmospheric species can be monitored. As the mission was designed to last for at least 15 years, with one IASI still to be launched, it will provide long and consistent time series. This paper illustrates the findings of the IASI mission for three key pollutants, and discusses the advantages and drawbacks of thermal infrared observation from space. The main advantage of IASI is its global coverage capability, with day and night observation, and its ability to sound remote regions (either not covered by air quality networks or located in countries where the information is not distributed). In contrast to in situ measurements, satellite observation is less accurate, averaged over larger areas determined by the instrument spatial resolution, and also integrated over altitude. For O3 and CO, it was shown that most of the information comes from the mid to upper troposphere, whereas ammonia measurements are representative of surface emissions due to its short lifetime combined with spectroscopic absorption in an optically transparent window. A critical parameter for IASI observation is thermal contrast, which determines the sensitivity of the observation close to the ground. As payload of an operational weather forecasting satellite, the mission also benefited from the near real time processing of the data, allowing the set-up of operational applications to feed information services (volcanic alerts, pollution forecast, etc.).

The continuity of the IASI program is ensured with its successor IASI-NG (Clerbaux and Crevoisier, 2013; Crevoisier et al., 2014), to be launched on MetOp-SG platforms that will continue the long-term observation record provided by IASI after 2021. From the optimized instrumental specifications (signal to noise improved by a factor of 2, as well as spectral resolution), it is expected that more accurate observation will be possible, with an improved sensitivity lower in the atmosphere. IASI-NG will be the infrared companion instrument of the Sentinel 5 series of UV–visible sounders, which will form the space segment of the Copernicus atmospheric service dedicated to atmospheric chemistry, air quality and climate.

Acknowledgments

This is an invited contribution to the special issue “Invited contributions of 2014 geoscience laureates of the French Academy of Sciences”. It has been reviewed by Didier Roche and Editor Vincent Courtillot. Cathy Clerbaux is very grateful to Gérard Mégie for giving her the opportunity to work on the IASI mission and to Marie-Lise Chanin for her scientific enthusiasm and continuous support. This work benefited from the contribution of several PhD students and post-docs both at LATMOS (former “Service d’aéronomie”) and ULB. The French scientists are grateful to CNES and CNRS for continuing scientific collaboration and financial support. L.C. is research associate with the F.R.S.–FNRS. The research in Belgium was supported by F.R.S.–FNRS and Belspo (ESA Prodex arrangements). The IASI mission is a joint mission of Eumetsat and the “Centre national d’études spatiales” (CNES, France). The IASI L1 data are distributed in near real time by Eumetsat through the Eumetcast system distribution. The authors acknowledge the French Ether atmospheric database (http://ether.ipsl.jussieu.fr), Cathy Boonne and Nathalie Poulet-Crovisier for their support. The Ixion orbitography software is available here: http://climserv.ipsl.polytechnique.fr/ixion.html.

2 From Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique (LMD), former Service d’Aéronomie (SA) and former Laboratoire de Physique Moléculaire et Applications (LPMA).