1 Introduction

To protect themselves against the multitude of aggressions from external sources, animals have developed a wide variety of defensive mechanisms. At the very simplest these mechanisms include moving away from sources of attack, whilst the most complex are those of the multifaceted immune system.

The immune response can be divided into two major forms, named innate and adaptive immunity. Innate immunity is genetically inherited in its entirety, without genetic recombination occurring at an individual level, and it is found in all Metazoans. The signalling cascades and other responses triggered by invading pathogens are the same across a species, regardless of the types of pathogen previously encountered by different individuals. On the other hand, the adaptive immune response is found uniquely in Gnathostomes, a Metazoan sub-group to which all vertebrates belong. Adaptive immunity between or within species is entirely reliant on the immunological history of each individual. Detailed discussions of the adaptive immune response can be found in articles presented in this issue, [1,2]. The hallmarks of this response include the generation of immune receptors in lymphocytes through somatic gene rearrangement and clonal expansion of activated lymphocytes. The adaptive immune system is also endowed with memory, allowing a rapid and directed response if a pathogen is re-encountered. Vertebrates thus benefit from the immunological experience gathered throughout their lifetimes, as well as a germ-line encoded innate response. The two systems act synergistically to provide short and long term protection against infection. While the vast majority of species may have appeared to be handicapped by having only ‘basic’ innate immunity, it is now obvious that this single type of immune response provides a robust answer to pathogen attack.

In terms of the scientific resources allocated, adaptive immunity long held ascendance over the innate response. This has largely been due to a focus on mammalian species, where the adaptive response was deemed to be sufficient and superior to any primitive innate relics. With the emergence of the importance of innate responses in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, AIDS and multiple sclerosis, the utility of studying this ancient form of defence is pressingly apparent. However, as mentioned above, all vertebrates possess both adaptive and innate immune systems. There is a constant dialogue between the two types of immune response, precluding the use of any vertebrate as an efficient model to study innate immune mechanisms without the confounding presence of other reactions. Other Metazoans, such as insects, have only innate responses and therefore represent the ideal opportunity to study this system in isolation. Over the past 20 years, the perceived status of the innate immune system has changed from an immunological backwater to that of centre stage importance in the battery of defences against pathogen attack.

As for any effective immune response, the innate system must be capable of doing three things: (i) recognizing a diverse array of pathogens; (ii) killing these pathogens once they are recognized; and (iii) avoid destruction of host tissues, i.e., there must be differentiation between self and non-self. What, then, does the innate immune system consist of and how has its study been tackled?

2 A model system – an important choice

From the 1920s, the common fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, was used as a model in the study of genetics and development. This easily maintained insect had several interesting characteristics, including a rapid life cycle and the random, spontaneous production of stable mutations with distinct phenotypes. It was possible to increase the rate of mutation in a generalised manner using chemical mutagens and in a more directed fashion using transformation methods. At the end of the twentieth century, the enormous base of information, along with the promise of one of the first completely sequenced genomes, led to the use of Drosophila in studies of the then emerging field of innate immunity. This choice of model system had serendipitous consequences on subsequent discoveries in innate immunity, particularly in the humoral arm which has primacy in Drosophila.

3 The humoral components of the insect innate immune system

As has already been stated, an organism under microbial attack must not only sense this, but it must also react to the aggression and kill the microbes without causing self-harm. In insects, a formidable number of chemical weapons have evolved to serve this purpose and they are known as the antimicrobial peptides (AMPs).

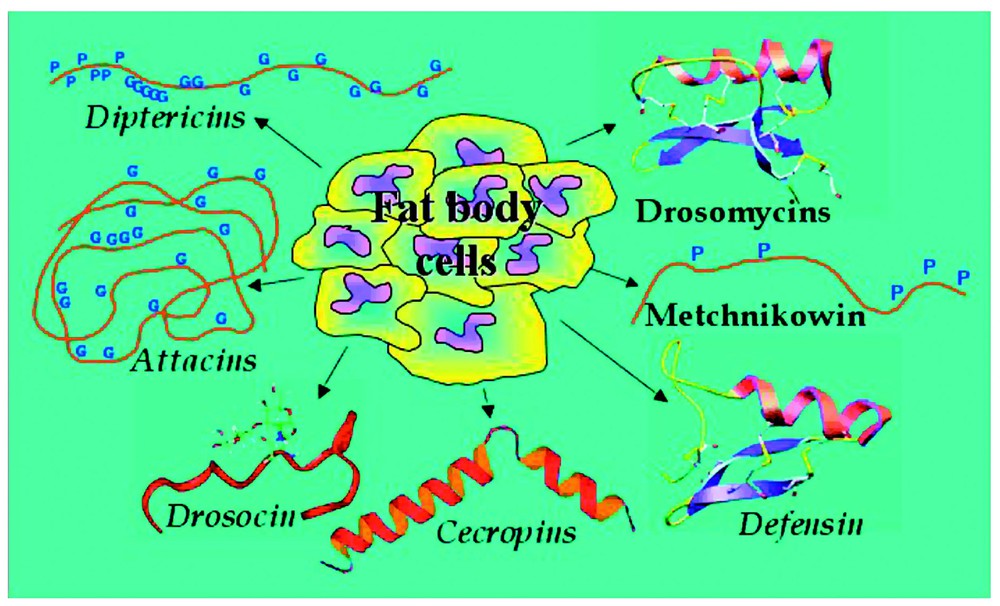

In Drosophila a total of 20 AMP genes have been identified and their peptide products fall into seven distinct families (Fig. 1) (reviewed in [3] and references therein). These peptides are largely adapted for inducible production from the fat body, an insect functional equivalent of the mammalian liver, but surface epithelia exposed to microbial attack are able to secrete them to a lesser extent [4,5]. Following production from the fat body, the AMPs are secreted into the haemolymph, where they interact with and destroy invading microbes. The peptides are structurally diverse, mostly small-sized (5 kDa), cationic molecules that are predominantly membrane-active [6]. Their activity spectra are directed either against fungi (Drosomycin, Metchnikowin), Gram-positive (Defensin) or Gram-negative bacteria (Attacins, Cecropins, Drosocin, Diptericins). It is assumed that these peptides are the main actors blocking the growth of invading microorganisms in the haemolymph, which bathes all the internal organs in the insect open circulatory system. Recent evidence has indicated that there may also be active synergy between individual peptides and other Drosophila immune-inducible molecules (DIMs), enhancing peptide activity [7].

The Drosophila melanogaster anitmicrobial peptides. The fat body of Drosophila melanogaster produces seven distinct antimicrobial peptides or peptide families. Drosomycins, Metchnikowin, Defesins, Cecropins, and Drosocin have been biochemically isolated from immune-challenged flies and their genes have been cloned. Only DNA studies have been carried out for Diptericins and Attacins and their activities inferred from those of homologous polypeptides isolated from other insects. For activity spectra refer to text.

In the early 1990s, an analysis of the promoters for AMP genes uncovered the presence of sequence motifs similar to those of the mammalian NF-κB response elements [8,9]. Using transgenically modified flies it was established that these motifs were essential for induction of the AMP genes after infection [10]. At around the same time, it was established that the participants in the NF-κB cytokine-induced activation cascade observed in mammalian immune responses had close similarities to those of the Toll signalling pathway, a pathway first described for its dorso-ventral patterning role during early embryogenesis in Drosophila (reviewed in [11]). The similarities between these two supposedly unassociated processes prompted an investigation into possible links between the Toll pathway and innate immune reactions in flies.

Using flies with mutations in various members of the Toll pathway, it was established that induction of the antifungal peptide Drosomycin and also resistance to fungi or Gram-positive bacteria required the participation of a fully functional Toll receptor and several other members of the pathway [12,13]. In parallel studies on a different, defined genetic locus, it was found that an unknown gene, referred to as immune deficiency (IMD), was essential for the induction of antibacterial AMPs and resistance to Gram-negative insult [14]. The data therefore indicated the involvement of at least two signalling cascades in immune signalling during the humoral response to microbial invasion. These two pathways took their names from the principal components known or deduced at the time; Toll and IMD.

4 The toll signalling cascade in immune reactions

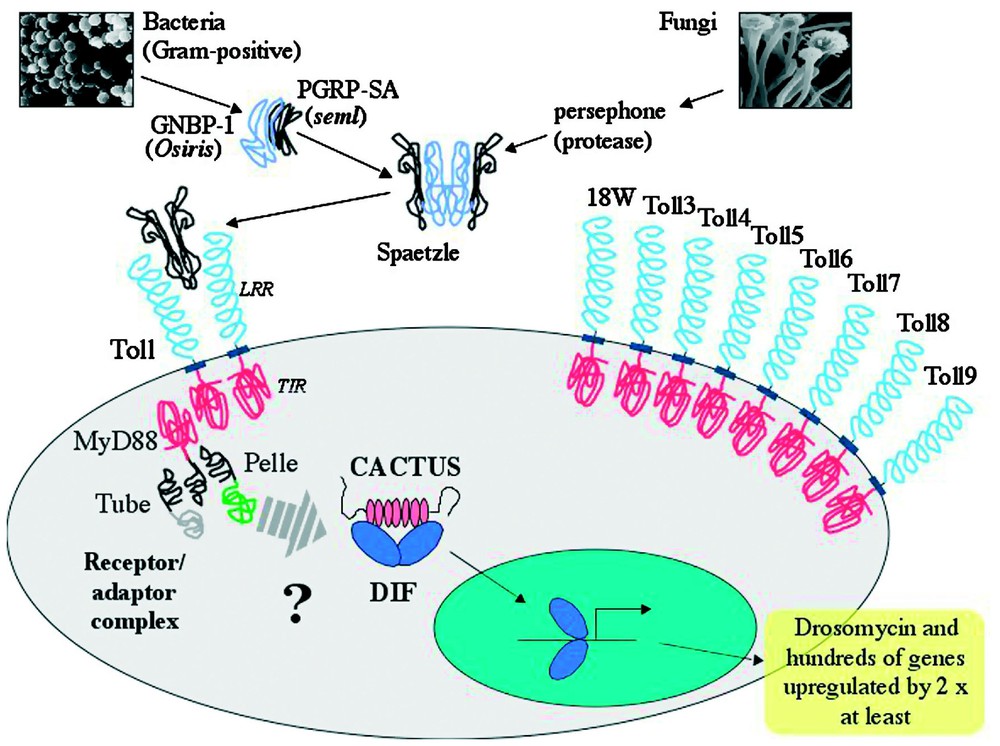

Current knowledge of the Toll signalling cascade in Drosophila is summarized in Fig. 2. Toll is a transmembrane receptor with an extracellular domain containing leucine rich repeats and an intracellular region with considerable similarities to the corresponding part of the interleukin 1 receptor (IL-1R) [15]. This intracellular region is commonly called the TIR domain. The current model for activation of the Toll pathway is that after receiving an extracellular signal of fungal or Gram-positive bacterial infection, the TIR domain of the Toll receptor interacts with the Drosophila homologue of MyD88 (DmMyD88) [16]. Aside from the TIR domain, DmMyD88 has a death domain (DD) [17], a conserved domain found in proteins like death receptors or adaptor proteins, which mediates protein–protein interactions. DmMyD88 transmits the signal to another DD containing protein, Tube [18], which in turn uses DD interactions to recruit a serine-threonine kinase named Pelle [19]. The association of these last three proteins and Toll itself constitute the receptor–adaptor complex formed upon signalling of either fungal or Gram-positive bacterial infection and disrupting any of the proteins leaves flies completely susceptible attack by these types of microbe [12,16].

Toll-dependent induction of immune genes by fungal and Gram-positive infections. The cysteine knot growth factor Spaetzle is activated through cleavage by blood proteases. At least two different proteolytic cascades are present, activated by either fungi or Gram-positive bacteria. Gram-positive bacteria are recognized by GNBP1 and PGRP-SA, thereafter activating an unknown proteolytic cascade. The only currently known participant in the fungal cascade is the protease Persephone. Once cleaved, Spaetzle interacts with the membrane receptor Toll. The current view is that as a result of Toll activation by Spaetzle, the receptor/adaptor complex, formed by the TIR domain of Toll and MyD88 along with the death domain proteins Tube and Pelle, triggers phosphorylation of Cactus by an as yet unidentified kinase. Phosphorylated Cactus is degraded and DIF translocates to the nucleus where it induces the expression of Drosomycin and many other genes. The Drosophila melanogaster genome contains eight additional genes coding for Toll-related proteins, all of which have intracellular TIR domains. Their roles in immunity, if any, remain to be fully established.

The signal passed through the receptor–adaptor complex results in the dissociation of an NF-κB protein from Cactus, the Drosophila homologue of mammalian IκB [20]. Whilst it is known that this dissociation is triggered by phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of Cactus, the identity of the kinase involved is currently still unknown. Pelle, an obvious candidate for this role, was ruled out as it was shown that it was not able to directly phosphorylate Cactus [21]. The NF-κB protein released by Cactus degradation is now able to translocate to the nucleus and regulate target genes. There are two NF-κB proteins under the control of the Toll pathway, Dorsal and Dorsal-related immunity factor (DIF) [22,23]. Both of these factors can act in Toll-controlled immune responses in Drosophila larvae but DIF is the major mediator of Toll signalling during fungal or Gram-positive bacterial infections in adult flies [24].

After the importance of the Toll pathway had been established in the innate immune defences of flies, a search for similar responses was undertaken in mammals. This resulted in the discovery of the mammalian Toll-like receptors (TLRs), of which at least ten human and nine mouse are now known to exist (reviewed in [25]). Within species, TLRs have been shown to have distinct roles in sensing particular microbial molecules or ligands (reviewed in [26,27]), thus acting as recognition receptors to make a direct connection with infectious non-self molecules. The TLR-generated intracellular signal to NF-κB activates the genes involved in the encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines and co-stimulatory molecules, forming the liaison between the innate defence and the activation of adaptive immune responses [26].

An important question that arose from the above findings was whether the Drosophila Toll receptor functioned in the same way as its mammalian counterparts or whether other upstream factors were required to interpret microbial signals prior to Toll activation. During embryonic patterning Toll is activated by proteolytically-cleaved Spaetzle (Spz), a cytokine-like cysteine knot polypeptide [28]. From mutant studies it was found that Drosophila Toll did not directly recognize microbial patterns and that immune triggering of the receptor was entirely dependent on cleaved Spz [29,30]. The next step was to identify the protease(s) involved in Spz cleavage following infection. During embryonic patterning, Spz is cleaved by the sequential activation of three serine proteases, Gastrulation defective, Snake and Easter [31]. However, immune activation of the Toll pathway remained normal in null mutants of these proteases, with wild type induction of the antifungal peptide Drosomycin [12]. During the search for members of any extracellular proteolytic cascades implicated in activation of the Toll pathway, it became apparent that there were at least two separate paths leading to cleavage of Spz. The second surprise was that these two paths used differential triggers of either fungal or Gram-positive bacterial infection. Although the signals leading to fungal activation of Toll are as yet unknown, cleavage of Spz and subsequent stimulation of the Toll receptor during Gram-positive infection can be achieved by the intervention of two pattern recognition receptor proteins [32–34]. The search for extracellular components and other possible elements involved in Toll signalling is currently being pursued, with a wealth of indices arising from the transcriptional profiles obtained after differential microbial infections [35,36].

In addition to Toll, Drosophila have eight other related genes encoding transmembrane receptors [37]. All Drosophila Tolls have complex stage specific patterns of expression with roles in fly development [38]. The six Spaetzle-like proteins that are essentially produced during embryonic and larval stages are ideal candidates as ligands for Toll receptors during these phases. Developmental activation of Tolls may also be driven by interactions of their leucine-rich repeat ectodomains with neighbouring cells, as has been seen for Toll and 18Wheeler [39,40]. Aside from a universal use in development, only two of the eight Toll relate genes, Toll-5 and Toll-9, have so far been shown to have an immune-related activity, with limited activation of Drosomycin in a cell culture assay [37,41]. In opposition to the situation seen in mammals, it therefore appears that only Toll itself has been co-opted from a developmental role to also fulfil an unambiguous and precise one in innate immune defence.

5 The IMD signalling pathway

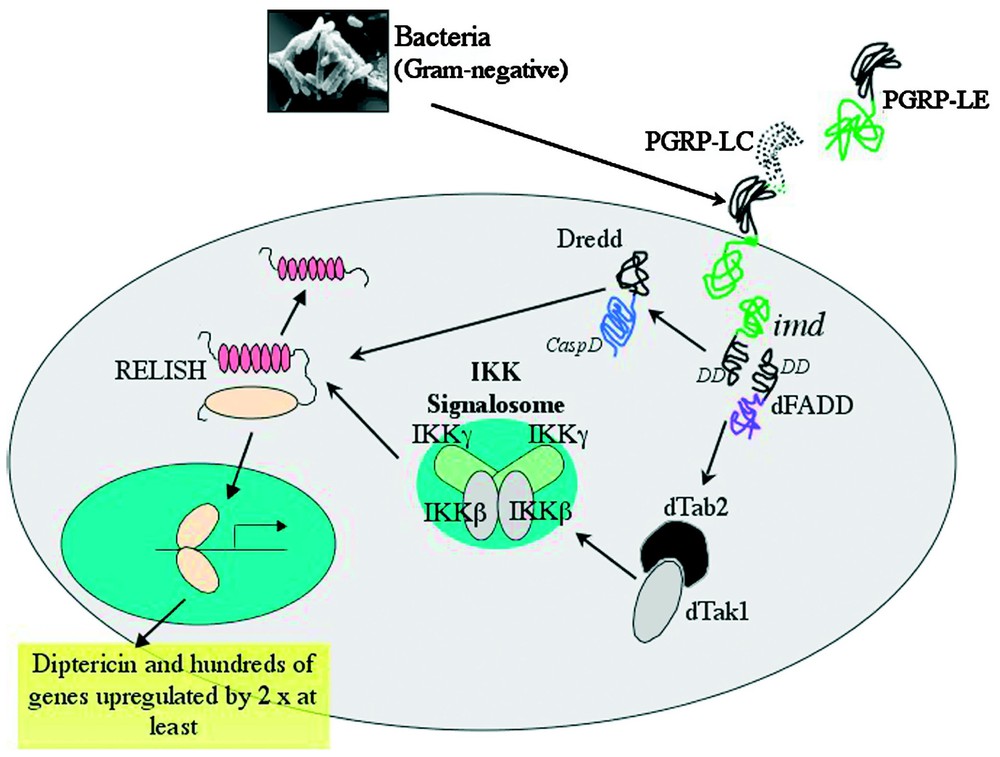

The IMD pathway is necessary for resistance to Gram-negative bacteria, controlling the inducible expression of the majority of AMPs (Diptericin, Attacin, Drosocin, Cecropin and Defensin) during systemic infections [14]. The existence of the IMD pathway was originally inferred from phenotypic analysis of mutant flies unable to resist Gram-negative infections, but with normal resistance against fungi or Gram-positive bacteria [14]. After a long period of investigation, the gene implicated in resistance to Gram-negative infection located at the IMD locus has now been identified. It encodes a 25 kDa protein with a DD and strong similarities to the mammalian TNF Receptor Interacting Protein, RIP [42]. A summary of the Drosophila IMD pathway is given in Fig. 3.

Immunodeficiency (IMD)-dependent induction of immune genes by Gram-negative bacteria. Upon Gram-negative bacterial infection, membrane bound PGRP-LC acts in conjunction with as yet unidentified co-receptors to induce the IMD pathway (for the role of PGRP-LE see text). It is thought that the death domain containing proteins IMD and dFADD interact with the caspase-8 homologue DREDD, sending a signal to the IKK (IκB kinase) signalosome complex. This complex contains homologues of mammalian IKKβ and IKKγ. Activation of this complex requires the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase component, the Drosophila homologues of TAB2/TAK1. Along with the DREDD caspase, activated signalosome participates in cleavage of Relish. The Rel-domain of Relish translocates to the nucleus where it induces expression of large numbers of genes, including those for several antimicrobial peptides.

Translocation from cell cytoplasm to nucleus of the third Drosophila NF-κB protein, Relish, is one of the key events in immune stimulation of the IMD pathway [43]. Relish is a latent trans-activator, with a Rel-homology domain and a C-terminal IκB-like, ankyrin-repeat inhibitory domain. Unlike DIF or Dorsal, the NF-κB proteins involved in Toll signalling, Relish is not inhibited by Cactus or another similar factor, but it remains inactive in the cytoplasm due to the presence of its own intrinsic ankyrin repeats [44,45]. Seconds after infection, the C-terminal inhibitory domain is endoproteolytically cleaved, freeing the Rel-homology domain. The caspase Dredd has been shown to be integral to this activation of Relish and the production of the Rel and IκB-like fragments [45]. After cleavage, the Rel subsection of Relish is able to translocate to the nucleus, where it controls the transcription of target genes. An IKK-signalosome equivalent, composed of proteins similar to the mammalian IKKβ and IKKγ subunits and encoded by the ird5 and kenny genes respectively, acts upstream to regulate signal-dependent processing of Relish, possibly by direct IKKβ kinase phosphorylation, prior to proteolytic cleavage [46–48].

RIP, the mammalian protein with strong similarities to IMD, acts as an adaptor molecule in the TNFR1 signalling pathway. It is required for NF-κB activation with the formation of a large receptor–adaptor complex, which includes RIP, FADD and caspase-8. [49,50]. Recent work in Drosophila suggests that Gram-negative bacterial insult triggers the formation of a similar receptor–adaptor complex containing at least IMD, the Drosophila homologue of FADD (dFADD) [51] and DREDD [52–54]. Although more direct biochemical evidence is needed to confirm the formation of this receptor–adaptor complex, the model is supported by genetic data placing IMD upstream of dFADD and DREDD, and dFADD upstream of DREDD.

At this point, it should be obvious that the receptors and ligands of the IMD signalling pathway are still relatively unknown, in contrast to the situation for Toll pathway components. Ironically, studies stimulated by the discovered implication of PGRPs in Toll signalling have brought to light a new component of the IMD signalling pathway, namely PGRP-LC. This putative transmembrane protein was recently shown to act upstream of IMD to activate transcription of the antibacterial peptide genes in response to Gram-negative infections [55–57]. The method of IMD pathway activation by PGRP-LC is still unclear and null mutants of the gene show a less drastic phenotype than has been reported for other loss-of-function mutants in the IMD pathway [56]. It is therefore possible that PGRP-LC may act with other receptor/co-receptor molecules as part of a larger recognition complex to sense Gram-negative bacterial infections. In keeping with this, over-expression of a haemolymph PGRP, PGRP-LE, led to constitutive activation of the IMD pathway and antibacterial peptide gene expression [58]. The relationships between PGRP-LE and PGRP-LC have not yet been established, but when a comparison is made to the situation found in the activation of the Toll pathway by PGRP factors, it is clear that no direct relationship need exist.

In light of the paucity of information regarding partners in the IMD pathway, considerable efforts are currently being made to join the dots. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis has already identified several hundred genes affected during the host response to Gram-negative infection and their participation in the IMD pathway is gradually being investigated [35,59]. A microarray study on Drosophila cell-lines demonstrated that in addition to the control of AMP synthesis, the IMD pathway is also implicated in cytoskeletal protein expression [60]. This overlap of control underlines the link between immune defence reactions and the tissue repairs required once the infection has been eliminated.

Although fat body cells release the overwhelming majority of AMPs during the fly's systemic immune response, barrier epithelia can also produce specific sets of AMPs in an infection-dependent manner [4,5]. Even though these reactions may include the induced expression of Drosomycin, systemically under the control of the Toll pathway, the epithelial response is governed uniquely by the IMD pathway. In contrast to the systemic expression of AMPs, a feature found only in insects that undergo complete metamorphosis, the local production of antimicrobial peptide genes is a general feature of host defence in multicellular organisms, conserved from plants to mammals (reviewed in [61,62]). The supra-control exhibited by the IMD pathway of immune responses at Drosophila epithelia may therefore indicate that, in evolutionary terms, the IMD pathway represents the ancestral immune defence pathway.

6 Cellular aspects of the insect innate immune system

As has been mentioned before, Drosophila immunity has two major arms, namely the humoral and cellular responses. Using Drosophila, it has been possible to make enormous progress towards the characterisation of the humoral branch, the results of which are discussed above. In comparison, the exploration of the cellular response in fly immune reactions is still largely in its early stages. This second facet of the innate immune response is dependent on the different types of Drosophila haemocytes, or blood cells. Fly larvae deprived of these cells are clearly more sensitive to infection than their normal counterparts [63] and sequestering haemocytes by injecting polystyrene beads increases the susceptibility of IMD mutant Drosophila to bacterial infection [64]. But what are mechanisms involved?

The majority of research carried out in the domain of Drosophila cellular immunity has focused on the larval stages of development. The larval stage has been preferentially used for studying the cellular response as it is the only stage during which all three types of Drosophila haematocytes are present, adult flies lacking both crystal cells and lamellocytes, and the capacity to produce any new blood cells [65].

The process of haematopoiesis in Drosophila and other insects has recently been the subject of extensive reviews [66–68], therefore the complex details of this process will not be treated in full here. In brief then, haematopoiesis occurs during Drosophila development and gives rise to the three haemocyte lineages: plasmatocytes, lamellocytes and crystal cells. The lymph gland, the haematopoietic organ found in fly larvae, contains undifferentiated haemocyte precursor cells, prohaemocytes, plasmatocytes and crystal cells [69–71].

In normal larvae, the circulating haemocyte population is made up of a majority of plasmatocytes and a small proportion (< 5%) of crystal cells [72,73]. Crystal cells contain crystalline inclusions that correspond to enzymes necessary for melanization [66], a process which is discussed later. Plasmatocytes are dedicated phagocytes [65,69] and their massive presence during development is not surprising as they play a fundamental role in the removal of apoptotic cells following tissue remodelling [65,74,75]. In adult flies the only haemocyte cell type present is the plasmatocyte and all of them are derived from the larval population [76].

7 Plasmatocytes and phagocytosis

As stated above, plasmatocytes are responsible for the disposal of both microorganisms and apoptotic cells in Drosophila larvae. The mechanisms by which they recognize damaged or non-self cells and engulf their targets are poorly understood. In mammals, receptors with broad range recognition spectra, such as class A and B Scavenger Receptors, participate in the identification and binding of microorganisms or apoptotic cells to phagocytes in a process known as tethering [77–79]. Tethering of the undesired cell to the phagocyte is achieved either through direct recognition of non-self factors or through the mediation of bound opsonizing molecules that flag the presence of non-self to the host. Molecules that could fulfil the role of direct non-self recognition have been found in flies and their implication in phagocytosis has been investigated. For example, disposal of apoptotic cells by plasmatocytes in the Drosophila embryonic stage was found to require Croquemort, a CD36, scavenger receptor homologue [74,75]. Elsewhere, in vitro studies have indicated that the Drosophila scavenger receptor dSR-CI participates in cell binding to both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [80,81]. However, although there is evidence of Croquemort or dSC-RI mediatation in phagocytosis, the mechanism triggering particle internalization remains unknown. The second possibility for announcing the presence of non-self targets to the plasmatocytes is the opsonization of the cell surfaces of invaders. Marking foreign cells in this way would signal their presence to the plasmatocytes. Due to their patterns of expression and their biochemical characteristics, it was proposed that thioester-containing proteins (TEPs) fulfilled the function of opsonizers in Drosophila [82]. Evidence to support this view has come from studies in another insect, Anopheles gambiae, where phagocytosis of Gram-negative bacteria was strongly reduced when transcription of a tep gene was impaired [83].

8 Lamellocytes and encapsulation

The third type of haemocyte found in Drosophila larvae is the lamellocyte. This kind of cell is rarely found in healthy individuals, but their production is massively induced if a foreign body, too large to be eliminated by plasmatocyte activity, is detected. This situation arises, for example, when Hymenoptera species parasitize Drosophila by laying their eggs in the larval haemocoel [84].

Once a foreign body has attained the haemocoel its presence is rapidly perceived by the circulating plasmatocytes and, in the case of parasite eggs, these then attach to the outer surface of the eggs [85]. Within a few hours, an increase in cell proliferation occurs in the lymph glands, paralleled by an increase in crystal cell numbers [86] and massive differentiation of lamellocytes [65]. The lamellocytes are released into the haemolymph where they migrate to the target and form a multilayered capsule. The large, flattened form of lamellocytes is ideal for encapsulating such foreign bodies and the parasite is eventually killed by asphyxiation or by the local production of cytotoxic free radicals, quinones or semiquinones [87]. The behaviour of lamellocytes marks them out as different to the other haemocytes found in Drosophila, in that they show certain characteristics of an adaptive response to a specific immune challenge.

The transition between plasmatocyte attachment to a foreign body and the encapsulation of this same mass by lamellocytes reveals the enormous amount of signalling which must occur in order to coordinate the appropriate response. Once the plasmatocytes recognize that they cannot eliminate the invader by phagocytosis, the message must be relayed to the lymph glands, where massive differentiation of prohaemocytes to lamellocytes is triggered. Mature lamellocytes must also be able to trace a path back to the invader and then attach to form a multilayered hermetic structure. The nature of the signals involved in these processes remains to be discovered.

9 Crystal cells and melanization

In Drosophila, at injury sites or in the lamellocyte-capsules formed around large non-self masses, a black pigment is deposed. This pigment is the end result of the activation of a biochemical pathway that converts tyrosine to melanin [88,89]. Melanization has been proposed to participate in rapid wound sealing, preventing the insect from leaking to death before the more lengthy epithelial healing process can be completed [90]. This view is supported by the observation that melanization-deficient Drosophila mutants which show excessive bleeding after injury also have reduced survival rates thereafter [91].

The recognition of non-self molecular patterns, such as β-1,3-glucans, peptidoglycan or LPS, has been shown to activate melanization in Bombyx mori [92] and Ceratitis capitata [93]. These same molecules initiate a proteolytic cascade causing rapid clotting of haemolymph in chelicerates. Studies in the horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus, have identified several important humoral- and haemocyte-produced components of this clotting cascade, that ultimately results in precipitation of the protein coagulogen into insoluble coagulen [94]. It is possible, then, that melanization is directly involved in coagulation or that the proteolytic cascades leading to the two processes have components in common. It is worth noting that at the moment, whilst the mechanics of melanization are known, the genes controlling induction of this process in Drosophila are less clear. Recently, however, a key control serpin that restricts phenoloxidase activity to the site of injury or infection was uncovered [95,96]. This serpin, Serpin-27 A, regulates the melanization cascade through the specific inhibition of prophenoloxidase processing by the terminal serine protease.

Where then do crystal cells fit into this picture and what role do they play? Crystal cells are non-adhesive haemocytes that contain phenoloxidase precursors and their disruption would release precursors for rapid production of the active enzyme, which could in turn continue the melanization cascade. These cells cannot, however, be the only source of phenoloxidase precursors available to Drosophila, as melanization occurs readily in the adult stage of flies, where crystal cells are always absent. At the moment the role for crystal cells as a rapid source of phenoloxidase remains plausible, if speculative. The proper function of this larval specific type of cell and the relationship between melanization and coagulation are among the many questions that need to be answered.

10 Conclusions

As for the majority of multicellular organisms, the first barriers against pathogen attack in Drosophila are the external surfaces, such as the cuticle, digestive tract or respiratory epithelia. These surfaces are physical barriers against penetration of pathogens into the body cavity. If microbes get past these barriers, the host must be able to recognise their presence and act accordingly.

It is clear that both humoral and cellular reactions contribute to insect innate immune defence against pathogens. In Drosophila, disrupting phagocytosis does not reduce survival of wild-type flies injected with E. coli. On the other hand, imd flies are unable to synthesize antibacterial peptides controlled by the IMD pathway and have increased mortality over controls in response to Gram-negative bacteria. The rate of mortality is increased even more if phaocytosis is also disrupted in these flies [64]. There is also evidence for direct links between these two branches of defence. For example, haemocytes do not appear to be an important source of antimicrobial peptides in Drosophila, as domino mutants have no circulating blood cells but show wild-type levels of peptide synthesis after injection with bacteria or fungi [63]. However, when infection occurs per os through ingestion of bacteria, domino and other haematopoietic mutants, such as l(3)hem, show decreased levels of the antimicrobial peptide Diptericin [97]. In certain circumstances haemocytes therefore appear to be able to coordinate antimicrobial peptide responses.

There has been a certain tendency to think that the two transduction pathways known to function in the humoral response are alike, with the intervention of similar molecules and general patterns of intracellular transduction. A closer examination of Toll and IMD signals reveals another story. The Toll pathway is truly humoral and although there is a membrane bound receptor (Toll) to deliver incoming messages across the cell membrane, there is no direct contact between this receptor and an invader. Indeed, the proteolytically cleaved form of Spaetzle is the only known extracellular ligand of Toll [29]. Further proteolytic events up-stream of Spaetzle cleavage are thought to amplify the initial non-self signal and increase the sensitivity of the response. Inside the cell, the partners in the signalling cascade are very close to those found in the NF-κB reactions of mammals. However, despite the diversity of extracellular routes that can activate the pathway, only two direct antimicrobial end-products are known (Drosomycin and Metchnikowin). The IMD pathway is different from this schema. Even though the participation of co-receptors, etc., may be required, there is direct recognition of non-self by a membrane bound receptor, PGRP-LC, which in turn transmits information about infection to the cell. This situation closely echoes that found for the mammalian TLRs, each of which is directly stimulated by a different non-self molecular signature. As has been mentioned, the relationships between intracellular components of the IMD pathway are not yet fully understood, but perhaps its most surprising aspect is the number of end-products. This pathway is known to be directly responsible for managing the production of Defensin, Attacins, Cecropins, Drosocin, and Diptericins. All the research carried out to date on the Toll and IMD pathways show that they are undoubtedly complementary in their functions, protecting the fly from diverse insults. It is also clear that they represent two different ways of dealing with infection.

Considerable progress has been made in the last few years in our understanding of certain aspects of the innate immune response. Genetic screens and mutant studies have been used to great advantage in this research but these techniques have their limitations. Classical genetic screens are time consuming and labour intensive. Disrupting the normal function of some genes has consequences too important for the organism to accommodate and no offspring are produced to allow phenotype analysis. With the introduction of high-throughput proteomic methods, there has been a resurgence in interest in the functional part of the equation. Increasing numbers of studies are being carried out on the proteome of Drosophila and other model organisms, to analyse the effects of infection on patterns of protein expression [98–100]. Another tool at the forefront of current research is the microarray, a method capable of simultaneously observing the transcriptional profiles of an organism across its entire genome. This technology has been used to good effect in the exploration of the innate immune response in Drosophila, where the differential patterns of gene expression uncovered have opened new vistas for future work [35,59,60]. The number of completely sequenced genomes becoming available from both hosts and pathogens will undoubtedly facilitate examination of certain aspects of the innate immune response. Nevertheless, with all the techniques currently in place as well as those being developed, Drosophila remains the best model organism for the study of the innate immune response.

Finally, it is interesting to note that, unlike the case for innate immunity, no organisms have been found with only an adaptive immune response, underlining the fundamental necessity of baseline responses provided by innate mechanisms. In autosoteric terms, perhaps innate really is enough.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor J.A. Hoffmann for his advice and encouragement and Dr M. Meister for careful reading of the manuscript. PI is financed through a grant from the European Commission; LT and CH are financed by the CNRS, France.