1 Introduction

E. coli β-galactosidase hydrolyzes lactose and other β-galactosides into monosaccharides (Fig. 2). The enzyme is the product of the lacZ operon and, as discussed in the accompanying articles, was central to the development of the operon model by Jacob and Monod. This short review will focus on the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme. Implications of the structure for the mechanism of action will be discussed and the structural basis for the widely-used property of complementation will be reviewed.

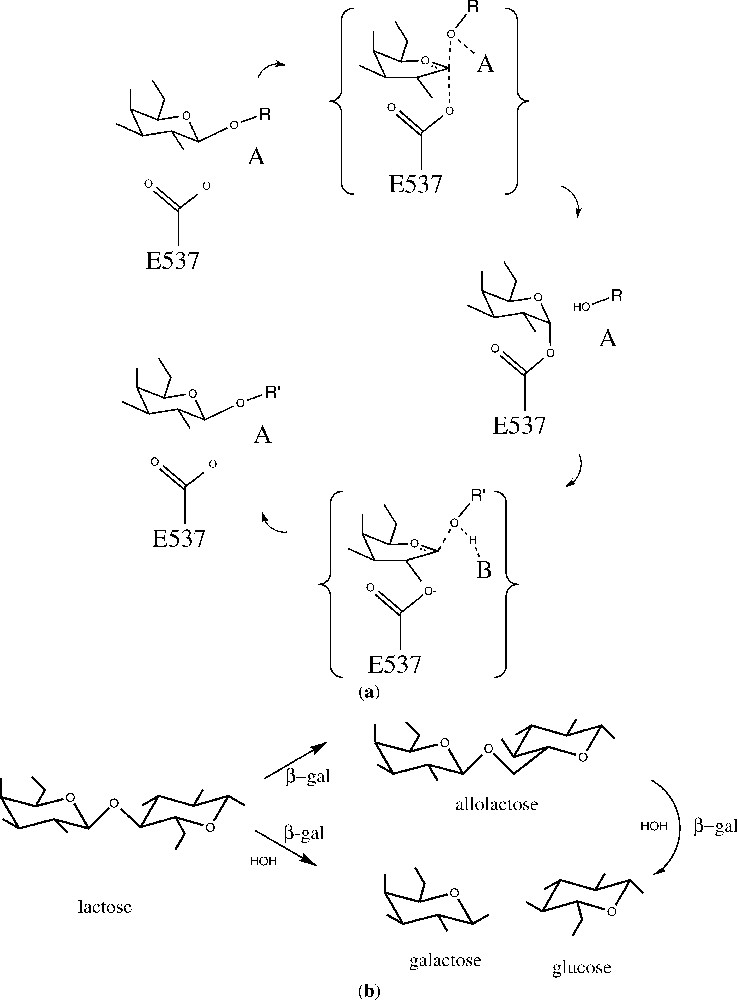

(a) Generalized outline for a double-displacement reaction catalyzed by β-galactosidase. In the first step (top), the substrate, a β-d-galactopyranoside with OR as the aglycon, forms a covalent α-d-galactosyl enzyme intermediate with the nucleophile Glu537 and with assistance from an acid, A (either Glu461 or a magnesium ion). Galactosyl transfer to the nucleophile is shown here as concerted with glycosidic bond cleavage, although this is controversial and may depend on the nature of the leaving group. In the second step (bottom), release of the intermediate is facilitated by a base, B (probably Glu461), which abstracts a proton from the acceptor molecule, R′OH. Galactosyl transfer from the enzyme is shown as stepwise, because there is substantial evidence that all substrates have a trigonal anomeric center in the transition state for this step. (b) General scheme for the action of β-galactosidase on the natural substrate, lactose. The enzyme can either perform hydrolysis (lower path) or transglycosylation (upper path). From [8].

2 Determination of the structure

The structure of β-galactosidase was first determined from a monoclinic crystal form with four independent tetramers in the asymmetric unit [1]. The presence of a very long cell edge () made this a technically demanding project, but by averaging over the 16 polypeptide chains in the four tetramers, it was possible to determine the structure. Subsequently another crystal form was identified with a single tetramer in the asymmetric unit [2]. This made it possible to extend the resolution of the structure determination to 1.7 Å and to analyze a series of complexes with inhibitors and other ligands.

3 Description of the structure

The β-galactosidase tetramer (Fig. 1) is comprised of four polypeptide chains, labeled A–D, each of 1023 amino acids. It is worth noting that the sequence was first determined the ‘old-fashioned’ way over a 10-year period by Irvin Zabin and his technician Audrey Fowler [3]. As confirmed by subsequent sequencing of the lacZ gene [4], as well as by the determination of the three-dimensional structure, the original Fowler–Zabin sequence was correct except for a ‘missing’ dipeptide and a few other minor changes.

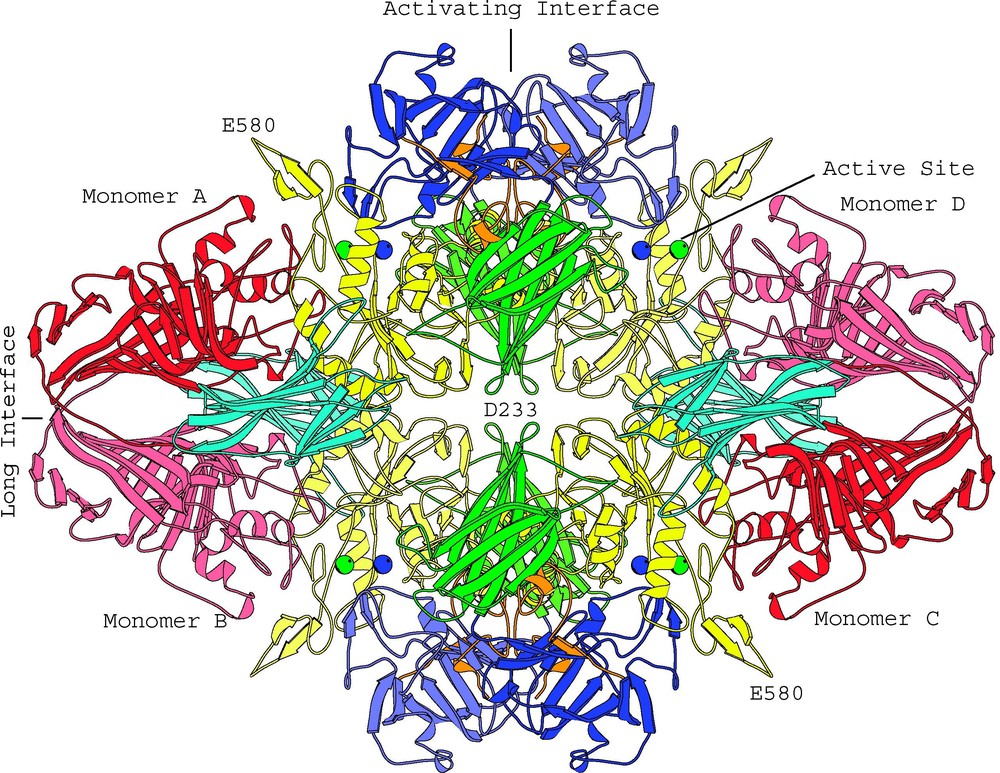

View of the β-galactosidase tetramer looking down one of the two-fold axes. Coloring is by domain: complementation peptide, orange; Domain 1, blue; Domain 2, green; Domain 3, yellow; Domain 4, cyan; Domain 5, red. Lighter and darker shades of a given color are used to distinguish the same domain in different subunits. The metal cations in each of the four active sites are shown as spheres: Na+, green; Mg++, blue. (From [2].)

Each 1023-amino-acid monomer is made up of five domains, 1–5, which are respectively colored blue, green, yellow, cyan and red in Fig. 1. Domain 3 has an or ‘TIM’ barrel structure with the active site located at the C-terminal end of the barrel.

In the tetramer the four monomers are grouped around three mutually-perpendicular two-fold axes of symmetry. These axes can be considered to form three distinct interfaces between different pairs of monomers. First, the ‘long’ interface, formed by the horizontal two-fold axis in Fig. 1, relates the A and B monomers. It also relates C with D. Overall, the surface area involved in this interface is about 4000 Å2. Second, the ‘activating’ interface, formed by the vertical two-fold axis in Fig. 1, relates A with D, and B with C. This interface involves a surface area of about 4600 Å2. A third, much smaller, interface, involving about 230 Å2, relates A with C and B with D [2].

4 The active site

The residues that form the active site are contributed by different segments of the polypeptide chain. Much of the active site is formed by a deep pit that intrudes well into the core of the TIM barrel in Domain 3. In addition, there are loops that come from the first and fifth domain of the same monomer. As well as these components from the same monomer, there is a loop that comes from Domain 2 of a different monomer and extends into the neighboring active site across the ‘activating interface’. As seen in Fig. 1, Monomer A donates its Domain 2 loop to complete the active site of Monomer D. Likewise, a loop from Monomer D completes that active site of Monomer A. Reciprocal donation and acceptance also occurs between Monomer B and C to yield a total of four functional active sites.

These active sites are well separated (Fig. 1) and presumably act independently. However, because it takes two monomers to complete an active site, individual monomers of the enzyme are presumably inactive.

5 Metal binding sites

Both Mg2+ and Na+ are required for maximal activity of β-galactosidase [5]. A magnesium ion was identified in the active site of both crystal forms of the native enzyme [1,2]. Several other possible Mg2+ binding sites were also identified in the higher-resolution structure although no functional significance was ascribed to these. Studies of crystals soaked with potassium and rubidium identified five putative sodium-binding sites. One of these is in the active site; the remaining ones are on the surface of the protein [2].

6 Mechanism of action

β-Galactosidase has two catalytic activities. First, it hydrolyzes the disaccharide lactose to galactose plus glucose. Second, it converts lactose to another disaccharide, allolactose, which is the natural inducer for the lac operon (Fig. 2b).

The enzyme has fairly strict specificity for the sugar in the galactosyl position, but is adept at hydrolyzing β-d-galactopyranosides with a wide variety of aglycones. Because of this promiscuity the allolactose mentioned above is ultimately converted by the enzyme to galactose plus glucose (Fig. 2b).

Also, the possibility of exploiting different substrates has allowed the introduction of a variety of substrates with useful chromogenic properties. These include X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) and ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside).

β-Galactosidase is a retaining glycosidase, where the product retains the same stereochemistry as the starting substrate. The two-step (double displacement) nature of the catalytic mechanism was first proposed by Koshland [6] and later demonstrated experimentally [7]. A generalized outline for the mechanism of action, based on a variety of evidence ([8] and references therein) is shown in Fig. 2a.

A series of crystallographic analyses have been carried out to try to visualize the presumed intermediates during catalysis [8].

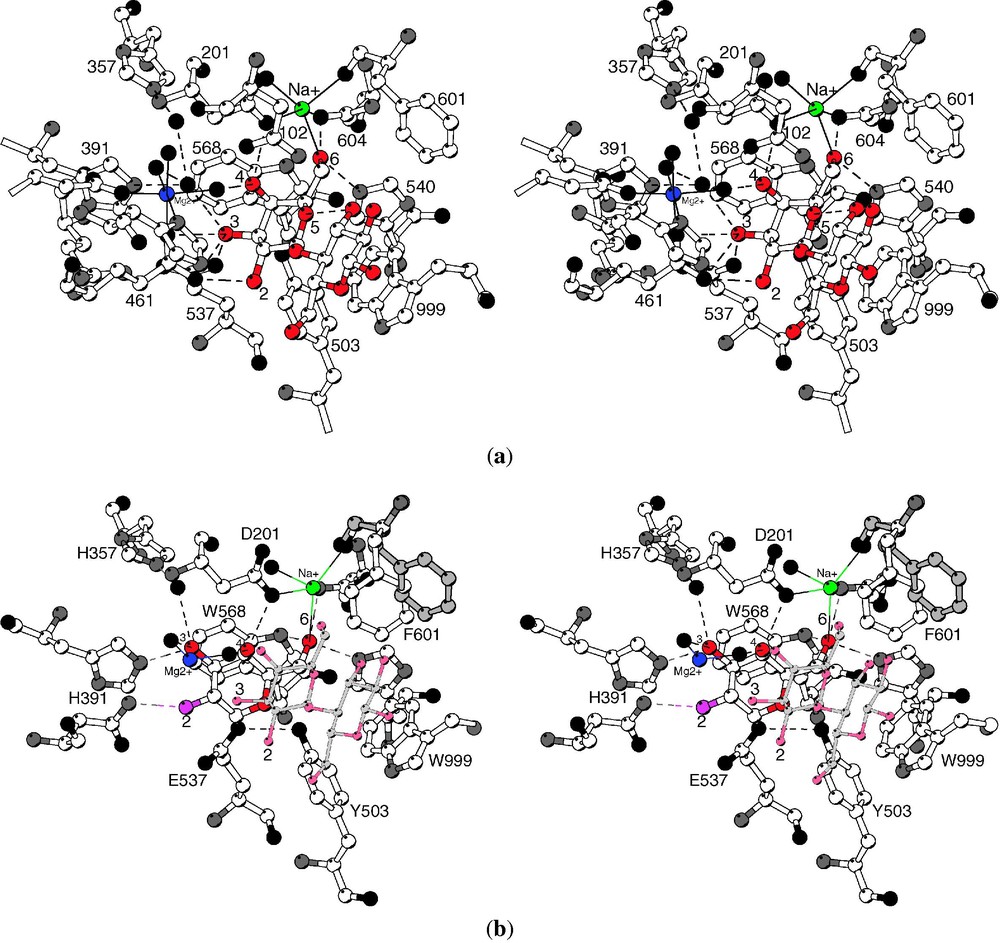

To mimic the early points in the reaction, natural substrates were bound to the mutant enzyme Glu537 → Gln (E537Q), which is catalytically incompetent [9]. Also the non-hydrolyzable substrate analogues isopropyl thiogalactoside and 2-F-lactose [10] were bound to the native enzyme. All of these ‘early-event’ ligands bind in a ‘shallow’ mode, stacking on the indole of Trp999 (Figs. 3a and 4a).

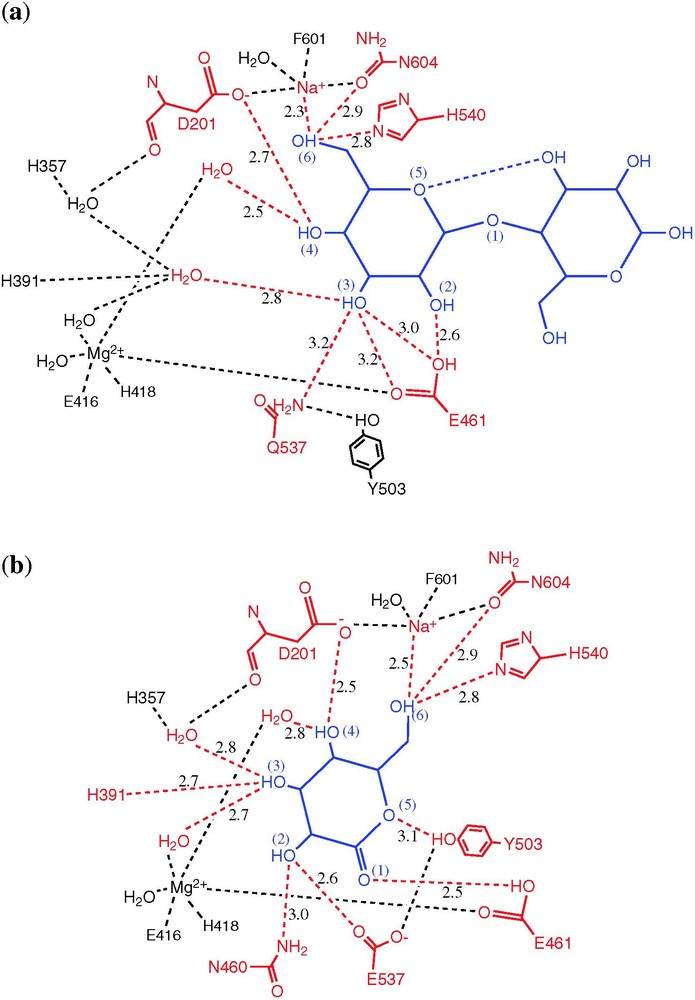

(a) ‘Shallow’ binding mode. Stereoview showing lactose bound to the E537Q variant. The galactosyl moiety makes many hydrogen bonds (shown as dashed lines) with the galactosyl hydroxyls, which are numbered, while the glucosyl moiety makes relatively few specific contacts. The sodium ion (green) directly ligands the lactose 6-hydroxyl while the magnesium ion (blue) makes no direct contacts to the lactose. Putative water molecules are shown as black spheres. (b) ‘Deep’ binding mode. Stereoview comparing the 2-F-galactosyl intermediate (open bonds) to the complex of lactose with mutant E537Q (gray bonds). From [8].

Schematic showing hydrogen bonds that are formed on ligand binding. The ligand is shown in blue, with contacting atoms in red. (a) Binding of lactose to the E537Q variant (shallow mode). (b) Binding of galactonolactone to native enzyme (deep mode). From [8].

To visualize intermediate points along the reaction pathway, use was made of substrates such as dinitrophenyl 2-F-galactoside, for which the breakdown of the enzyme-substrate adduct is much slower than its formation [10]. Such compounds were found to form a covalent adduct with Glu537, as expected, with the galactosyl ring moved somewhat deeper into the active site.

To mimic the presumed oxocarbenium ion-like transition state, galactotetrazole and galactonolactone were used. These compounds are trigonal at the C1 carbon and bind tightly [11,12]. Both of these transition state analogues bind in a ‘deep’ mode, with Glu461 contacting the atom that corresponds to the glycosidic oxygen (Figs. 3b and 4b).

The product of the normal catalytic cycle, galactose, was also observed crystallographically to bind in the ‘deep’ mode [8].

In summary, analogues of the starting substrate bind in a ‘shallow’ site at the mouth of the active site, while intermediates, transition state analogues and the product galactose penetrate 1–4 Å deeper into the active site. In both modes, the galactosyl 6-hydroxyl ligands the active site sodium ion, but a direct interaction with the magnesium ion was not seen with any ligand (Figs. 3 and 4). For the intermediate and surrogate transition-state complexes (but not the product galactose), binding was associated with a substantial conformational change in which the 794–804 loop from Domain 5 moves up to 10 Å closer to the active site.

The first half of the reaction cycle (Fig. 2a) involves cleavage of the glycosidic bond, formation of the covalent galactosyl enzyme intermediate with Glu537, and release of the aglycon [13,14]. Whether this occurs by Lewis catalysis by the magnesium ion, or Brønsted catalysis by Glu461 has been somewhat controversial [15]. Because none of the ligands studied crystallographically make direct contact with the magnesium ion (Fig. 4), it would seem that direct electrophilic attack by this ion is unlikely. Also the transition state analogues suggest that Glu461 is in a good position to donate a proton to the glycosidic oxygen, supporting its role as an acid catalyst for galactosylation [8]. Because the magnesium ion does interact directly with Glu461, however, it may contribute to the role of this residue.

The second half of the reaction cycle, degalactosylation, is thought to occur via the formation of a trigonal oxocarbenium ion-like transition state that forms only in the presence of both incoming and leaving groups.

As shown in Fig. 2b, β-galactosidase not only hydrolyzes lactose, but also acts as a transglycosylase, producing allolactose. In the crystallographically studied complexes, the moiety occupying the aglycon site generally has few specific interactions with the enzyme, and is poorly ordered. This somewhat promiscuous binding may reflect the physiological requirements of the enzyme for a balance between transglycosylation and hydrolysis. If the binding of glucose at this site was both specific and tight, then transglycosylation would be predominant. Conversely, if the binding were very weak, then hydrolysis would dominate.

7 Structural basis for α-complementation

The deletion of residues from the amino-terminus of β-galactosidase (classically residues 23–31 or 11–41) results in inactive dimers (called α-acceptors). By supplying peptides that include the missing residues (α-donors), catalytic activity can be recovered. Two common α-donors encompass residues 3–41 or 3–92. This phenomenon of α-complementation [16,17] is the basis for the common blue/white screening used in cloning and other procedures.

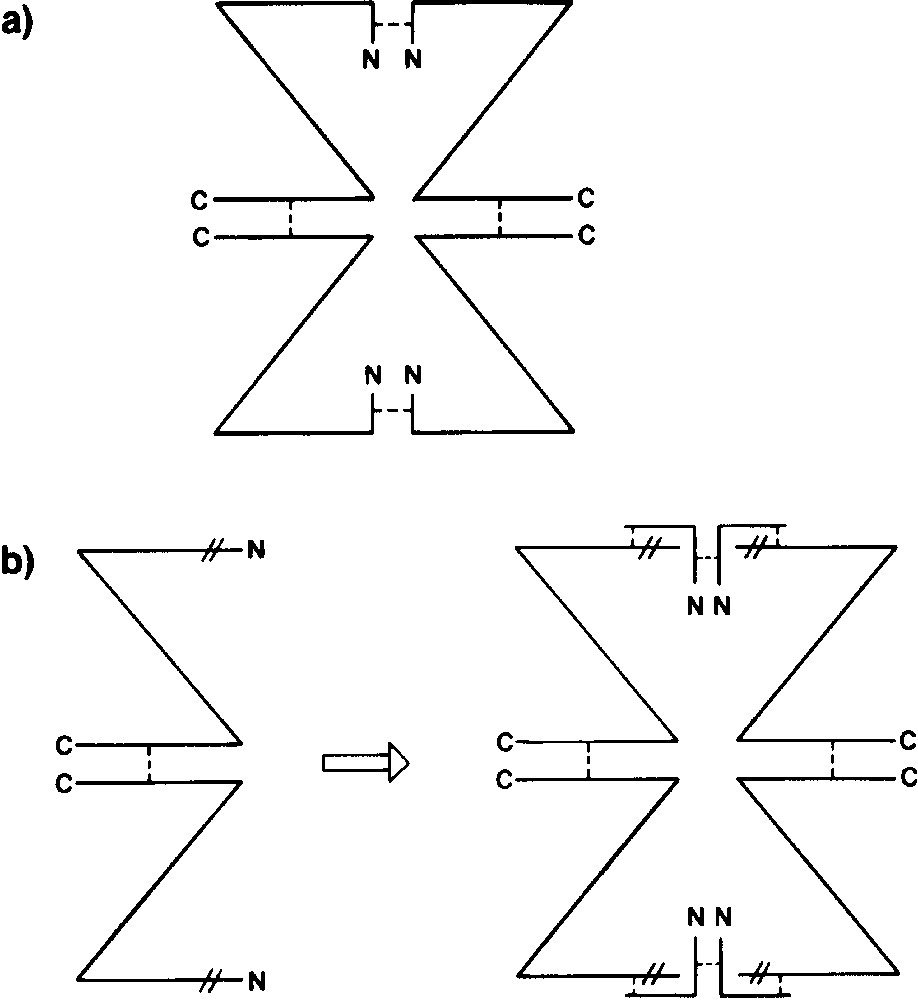

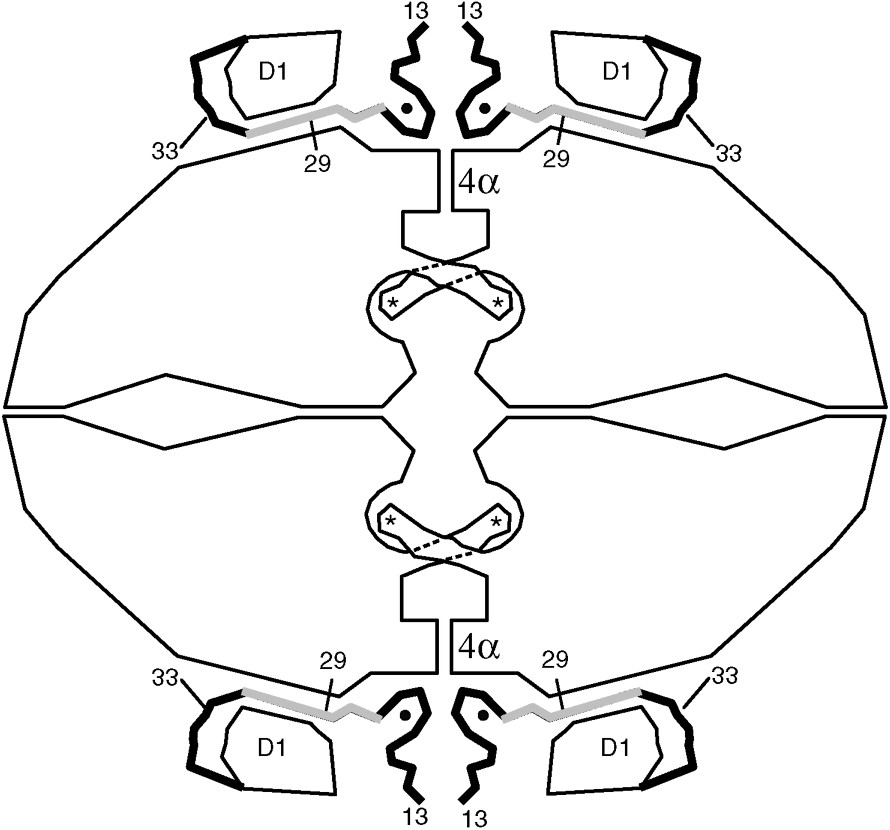

Fig. 5 is an early sketch intended to illustrate the key features of the α-complementation phenomenon [17]. The figure is based in large part on work from Zabin's group and, although drawn over a decade prior to the determination of the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme, is remarkably prescient. Fig. 6 is a more elaborate sketch, based on knowledge of the structure. As shown in Fig. 5a, intact, active β-galactosidase is tetrameric. Because deletions at the N-terminus result in inactive dimers (Fig. 5b), it was inferred that the N-terminal residues must mediate dimer–dimer binding to form the active tetrameric enzyme. It was also inferred that the monomer–monomer interactions that stabilize the dimer must be provided by the C-terminal part of the polypeptide chain (Fig. 5b). Finally it was inferred that the α-donors would reconstitute the dimer–dimer interface to recover active tetramers (Fig. 5b). Inspection of the three-dimensional structure (Figs. 1 and 6) verifies all of these key elements. The interface that is disrupted by deletion of residues from the N-terminus is the so-called activation interface. This interface is vertical in Figs. 1, 5 and 6. It includes a region where four α-helices come together (labeled 4α in Fig. 6) and also a region of contact between residues 13–23 of the respective monomers. In addition, residues 272–288 extend across the interface to complete the active site of the apposed monomer. The latter arrangement explains why the dimers are inactive. The role of residues 11–41 in stabilizing the tetrameric structure seems straightforward. Segment 13–23 contributes directly to the dimer–dimer interface (Fig. 6). Also segment 29–33 passes through a ‘tunnel’ (Fig. 6), which presumably ‘anchors’ residues 13–23 to the rest of the monomer. The deletion of residues 23–31 in the alternative α-acceptor also presumably disrupts both the dimer–dimer interface and the ‘tunnel’ interaction. It is noteworthy that the two classical α-donors (residues 3–41 and 3–92) both include residues 13–23 plus 29–33 (Fig. 6). This suggests that a successful α-donor needs to both reconstitute the dimer–dimer interface and, in addition, provide residues 29–33 so that the α-donor can be anchored to the remainder of the monomer.

The oligomeric structure of β-galactosidase and α-complementation. Enzyme monomer is depicted as Z. N- and C-terminal portions are indicated as N and C, respectively. (a) Biologically active tetrameric enzyme. Non-covalent forces (- - - -) that maintain quaternary structure are shown at N- and C-terminal regions. (b) lacZ deletion mutant M15, which removes amino acids 11–41 (| |), prevents formation of active tetramer and results in production of inactive dimer. If an α-donor, such as residues 3–92, is provided, dimer–dimer interaction is restored, and the enzyme can assume an active quaternary structure. This figure is from Weinstock et al. [17] and is “based on work of and discussions with F. Celada, A. Fowler and I. Zabin”.

Sketch summarizing key features of the β-galactosidase tetramer. At the amino-terminus, residues 1–12 are not seen in the electron density map due to presumed disorder. Residues 13–50 (shown as thick lines) pass through a tunnel between the first domain (labeled D1) and the rest of the protein. The region shaded gray (residues 23–31) is deleted in one of the α-donors. A magnesium ion (shown as a small solid circle) bridges between the complementation peptide and the rest of the protein. The four active sites are labeled with asterisks. The activation interface runs vertically through the middle of the figure. A part of this interface is a bundle of four α-helices in the region labeled 4α. When the activation interface is formed the four equivalent loops that include residues 272–288 extend across the interface to complete the active sites within the four recipient subunits.

8 Why is β-galactosidase so large?

E. coli β-galactosidase is a 464-kDa tetramer, yet its normal substrate is a simple disaccharide. Why is the protein so large?

Structural and sequence comparisons show that β-galactosidase belongs to the so-called ‘ superfamily’ of glycosyl hydrolases [18–20]. As noted above, the active site is built around the barrel in Domain 3. Such a domain is common to many other glycohydrolases.

Comparison of the structures of these proteins suggests that β-galactose arose from a prototypical, monomeric, single domain barrel with an active site that could accommodate extended substrates [21]. The subsequent addition and incorporation of elements from other domains could then have reduced the size of the active site to better hydrolyze the disaccharide lactose and, at the same time, to facilitate the production of inducer, allolactose. While changes such as this could account for some increase in size of the enzyme, it is not clear why it needs to be tetrameric; indeed some β-galactosidases, e.g., from Lactobacillus delbrueckii, are known to be dimeric [22].

Acknowledgments

Much of the structural analysis described here is due to the efforts of two exceptionally talented graduate students; Ray Jacobson was primarily responsible for the initial determination of the three-dimensional structure of the protein while Doug Juers extended the analysis to high resolution and determined the structures of many enzyme-ligand complexes. The work was supported in part by NIH grant GM20066.