least significant difference

TDMtriadimefon

HEXhexaconazole

RGRrelative growth rate

NARnet assimilation rate

DAPdays after planting

SPstarch phosphorylase

SSsucrose synthase

1 Introduction

The traditional means of increasing crop productivity are reaching their limits, and the increasing demand for plant production necessitates new strategies for future improvements in crop yields [1]. The identification of the methods responsible for manifestation of growth and yield has now become one of the most important tasks to provide food security for the future generation. It has been widely accepted that plant growth and development is controlled by the plant hormones, which are endogenously produced by the plants. However, synthetic plant growth regulators are also increasingly used to modify growth, development, stress behaviour, as well as qualitative and quantitative yield of crop plants. Plant-growth regulators open new opportunities to improve agricultural crop yield by circumventing several barriers imposed by genetics and environment. Manipulating the crop morphology by using plant growth regulators also increases the utilisation of solar radiation and alter photo-assimilate distribution in favour of yield increment [2].

The responses of plant growth regulators may vary with plant species, variety, age, plant, environmental conditions, physiological and nutritional status, stage of development and endogenous hormonal balance [3]. Plant-growth retardants are widely used to modify canopy structure, yield, and stress tolerance in many crop plants [4]. Triazole compounds such as triadimefon (TDM), propiconazole (PCZ), hexaconazole (HEX), paclobutrazol (PBZ), etc., are widely used as fungicides, and they also possess varying degrees of plant-growth regulating properties [5,6]. Triazole acts as a plant-growth regulator, and also influences hormonal balance, photosynthetic rate, enzyme activities, lipid peroxidation, and yield components in various crop plants [7]. Triazole inhibits the cytochrome P-450-mediated oxidative demethylation reaction, as well as those that are necessary for the synthesis of ergosterol and the conversion of kaurene to kaurenoic acid in a gibberellin biosynthesis pathway [8].

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), also known as Tapioca, Mandioca, and Yucca, a bushy shrub belonging to the Euphorbiaceae family, is an important food crop, cultivated throughout the tropics for its enlarged tuberous roots. The tubers are used in the sago industry for starch extraction and grown in rain-fed areas, where a number of sago and starch mills exist. In addition, the boiled tubers are consumed as staple food. The leaves of tapioca are rich in protein serving as an excellent cattle feed. It is an important daily source of starch for 300–600 million people around the world. The tuber contains 30 to 35% starch and appreciable amounts of calcium and vitamin-C.

Gibberellins and cytokinins are broadly used to induce bulb formation and increase the yield [5]. Yield enhancement in tuber crops like tapioca will be beneficial to the farmers [9] if experiments can determine the right type and concentration of the triazole compound. A lot of work has been done on the effect of triazole compounds on stress protection in various plants. Previous works revealed the influences of TDM on the antioxidant metabolism and ajmalicine production [10], salt stress protection [11], and alteration in floral qualities [12] by PBZ in the medicinal plant, Catharanthus roseus. However, work aiming at increasing the growth, yield, and quality using triazole compounds in tuber crops like tapioca is scanty. Hence, a study becomes essential to evaluate the effect of triazole compounds on the growth and metabolism of tapioca. In this study, it is proposed to evaluate the effect of triazole compounds, viz. TDM and HEX, on the growth, yield, and carbohydrate metabolism of M. esculenta under field conditions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant culture and triazole applications

The land was prepared by ploughing thoroughly five times to a depth of 35 cm and the soil was a sandy loam, without any stones and pebbles. The farmyard manure was applied at the rate of 10 tonnes per hectare. The stem cuttings of Manihot esculenta Crantz. cv-H-226 were obtained from the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, India. The stem cuttings of uniform thickness having three nodes were used for planting. The stem cuttings are dipped for 10 min in 1% Bavestin before planting to avoid fungal infections. Each stem cutting was planted in a plot of 1.5 ×1.5 to a depth of 5 cm inside the soil, and a completely randomised block design (CRBD) was used for this experiment.

No inorganic fertiliser was used throughout the experiment. Only groundwater was used for irrigation. 20 mg l−1 TDM and 15 mg l−1 HEX were used for the treatments to determine the effect of these chemicals on the growth and metabolism of cassava. One litre of 20 mg−1 TDM and 15 mg−1 HEX solution per plant was used for the treatments and control was treated with one litre of irrigation water. The treatment has been applied for 25, 45, 65, and 100 days after planting (dap) by soil drenching. The electrical conductivity of the soil was 0.21 dsm−1, and pH was 6.8 after the treatment. The average temperature was 32/26 °C (maximum and minimum), and the relative humidity (rh) varied between 60 and 75% during the experimental period.

TDM [1-(4-chlorophenoxy)-3,3-dimethyl-1-(1H-1,2,4-triazole-1-y1)-2-butanone] [C14H16ClN3O2], m.w. 293.75, has been obtained from Bayer India Ltd, Mumbai, and HEX (2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-1-(2H-1,2,4-triazole-1-y1)hexan-2-ol) [C14H17Cl2N3O], m.w. 314.2, has been obtained from Rallis India Ltd., Mumbai.

Plants were harvested randomly on 40, 80, 120, 160, 200, and 240 DAP, and separated into stem, leaf, root, and tuber. Tuber was used for determining growth, yield, and carbohydrate metabolism.

2.2 Growth parameters

The total leaf area of the plant was measured using a LICOR photoelectric area meter (model L1-3100, Lincoln, USA) and expressed in square centimetre per plant. The length of the main stem and of its branches up to the tip was measured and recorded as the total stem length. The internodal length was calculated by measuring the length of the stem from the seventh to fourteenth node, and it was divided by the number of nodes. The length of all roots was measured from the origin to the tip, and summed up as recorded to the total root length per plant. The root with pigmentation is recorded in the tuber and is taken into account in the root system. Plants harvested at random were separated into leaf, stem, root, and tuber. Then the material was dried in an oven at 60 °C until constant dry weight was obtained; the dry weight was expressed in grams per plant.

2.2.1 Relative growth rate

The relative growth rate (RGR) was analysed by using the dry weight and leaf area [13] by using the following equation:

time of first harvest

time of next harvest

total plant dry weight at time

total plant dry weight at time

natural log value

2.2.2 Net assimilation rate

total plant dry weight at time

total plant dry weight at time

total leaf area at time

total leaf area at time

time of first harvest

time of next harvest

natural log value

2.3 Carbohydrate content estimations

Starch content was estimated following the method of Clegg [14]. Soluble sugars (reducing and non-reducing) were estimated following the modified method of Nelson [15]. Sucrose content was estimated by the method of [16].

2.4 Carbohydrate metabolising enzymes

2.4.1 Starch phosphorylase (SP) (α-1, 4-glucan phosphorylases, EC: 2.4.1.1)

Starch phosphorylase activity was assayed following the method of Gibbs and Turner [17]. The starch phosphorylase activity was expressed in units = mg of inorganic phosphate liberated per minute per milligram enzyme protein.

2.4.2 Acid invertase (β-d-fructofuranoside fructohydrolase, EC: 3.2.1.26)

The crude enzyme extract was prepared and assayed following the method of Schaffer et al. [18]. The invertase activity was expressed in units = moles of reducing sugar formed per hour per milligram protein.

2.4.3 Sucrose synthase (SS)(UDP-glucose, d-frutose-2-glycosyl transferase, EC: 2.4.1.13)

The sucrose synthase was extracted and estimated by following the method of Glavier et al. [19]. The results were expressed in units = mg of reducing sugars released per minute per milligram protein.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The data was analysed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) as described by the method outlined by Ridgman [20]. Means were compared between treatments from the error mean square by LSD (Least Significant Difference) at the and confidence level using Tuckey's [21] test.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Effect of TDM and HEX on growth parameters of cassava

3.1.1 Effect of TDM and HEX on total stem length

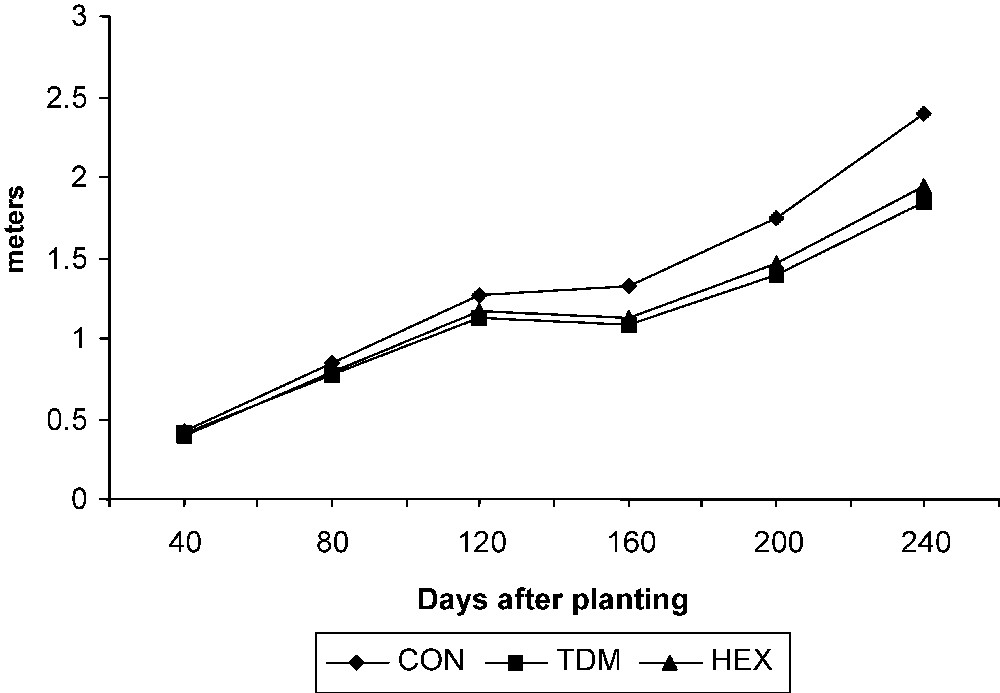

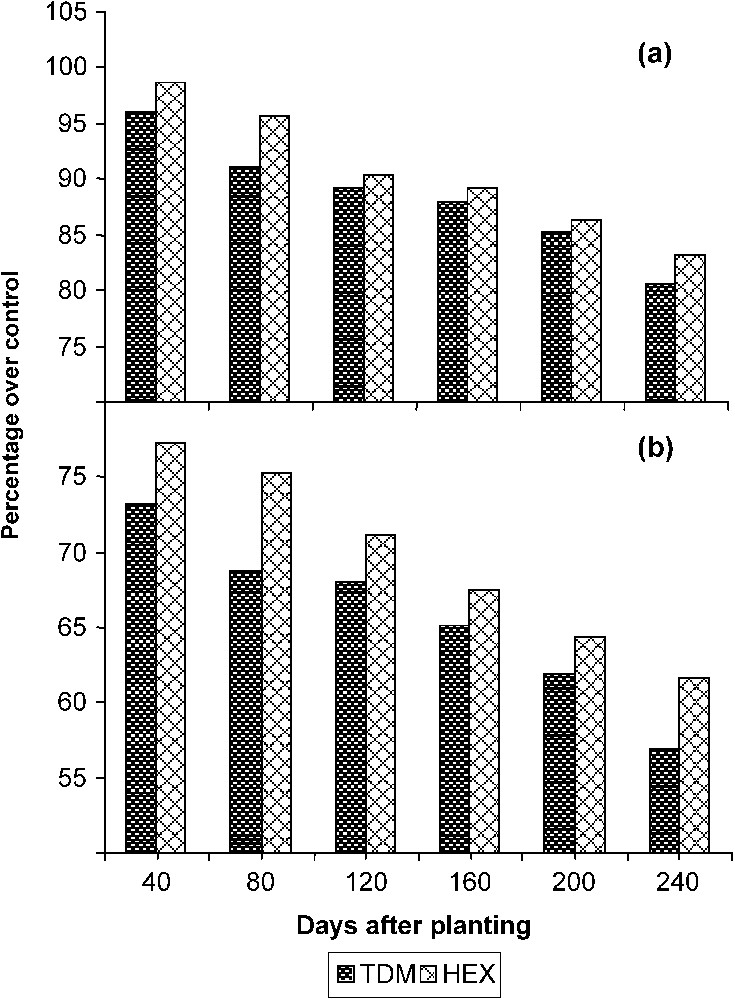

The total stem length increased with the age in the control and treated plants. TDM and HEX treatments inhibited the growth of the stem when compared to control and it was 77.33 and 81.26 POC on 240 DAP respectively (Fig. 1). Internodal growth was inhibited by the triazole treatments (Fig. 2a). TDM and HEX inhibited the internodal length when compared to control and it was 19.39 and 16.87 percent lower than controls on 240 DAP respectively.

Triazole-induced changes in the stem length of cassava. Values are given as a mean of seven experiments in each group.

Triazole-induced changes in (a) the internodal length and (b) the total leaf area of cassava. Values are given as a percentage over control.

Triazoles acts as antigibberellins, controls shoot growth by inhibiting the production of gibberellins, which are responsible for the cell elongation of shoots and leaves [22]. The growth-retarding effect of triazole is caused by the inhibition of GA biosynthesis, as observed in Cucurbita maxima [23]. Reduced height is a consequence of triazole-induced GA inhibition exemplified by reduced internodal elongation. Triazoles also reduced the cell number, length and width of the xylem cells [5].

3.1.2 Effect of TDM and HEX on total number of leaves

The total number of leaves per plant (Table 1) decreased in the triazole-treated plants. The reduction in the number of leaves was higher in the TDM-treated plants when compared to HEX and it was lesser by 14.32 and 10.58 percentage when compared to control on 240 DAP. The total leaf area (Fig. 2b) increased with the age in the control and treated plants. TDM and HEX treatments inhibited the leaf expansion when compared to control. Among the triazoles, the inhibition of leaf expansion was more in TDM treated plants when compared to HEX, and it was 56.89 and 61.67 POC respectively on 240 DAP. The reduced leaf area in triazole treatment may be due to the increased ABA content and reduced gibberellin biosynthesis induced by triazoles [24].

Triazole induced changes in the number of leaves of cassava (values are the mean of seven replicates, expressed in number plant−1)

| DAP | CON | TDM | HEX | F ratio | LSD | Group comparison |

| 40 | 32.00 | 30.99 | 31.58 | NS | 3.82 | |

| 80 | 104.00 | 99.03 | 101.03 | NS | 3.61 | |

| 120 | 142.00 | 134.57 | 132.48 | * | 4.24 | |

| 160 | 196.46 | 183.98 | 180.67 | ** | 6.51 | |

| 200 | 241.57 | 215.79 | 217.79 | ** | 7.42 | |

| 240 | 292.23 | 250.18 | 261.10 | ** | 8.98 | CON TDM HEX |

3.1.3 Effect of TDM and HEX on total root growth

Triazole treatments increased the total root growth marginally at early stages of growth (Fig. 3a). Later it declined in the triazole-treated plants. Reduction in root length was associated with an increase in the diameter of the roots, which can be correlated with the increased root DW. TDM stimulated adventitious root formation in bean hypocotyls [5]. Paclobutrazol increased the diameter and length of the fibrous roots and enhanced the lateral root formation in wheat seedlings [25].

Triazole-induced changes in (a) root length, (b) root fresh weight, and (c) root dry weight of cassava. Values are given as a percentage over controls.

3.1.4 Effect of TDM and HEX on fresh and dry weights

The total FW of the stem increased with the age in the control and treated plants. The triazole treatment marginally increased the FW up to 120 DAP. After 120 DAP, it showed a decline. Among the triazole treatments, HEX inhibited the stem FW largely when compared to TDM, and it was 89.50 and 92.77 POC on 240 DAP (Table 2). The total leaf FW of M. esculenta increased with the age of the plant. Triazole treatments inhibited the leaf FW at all growth stages. Among the triazole treatments, HEX inhibited the leaf FW largely when compared to TDM, and it was 75.81 and 79.12 POC on 240 DAP (Table 2). The total FW of the root increased with the age in the control and treated plants. The increase in root FW was high during the harvest stage. Root FW (Table 2) increased largely in the triazole-treated plants as compared to control. Among the treatments, TDM caused a more significant increase in root FW than in HEX-treated plants, and it was 107.17 and 105.59 POC, respectively, on 240 DAP. The total FW of the tuber increased with the age in the control and treated plants. Triazole treatment significantly increased the FW of the tuber. TDM and HEX enhanced the tuber FW largely when compared to control, and it was 132.17 and 130.59 POC on 240 DAP.

Triazole-induced changes in the fresh weight of cassava (values are the mean of seven replicates expressed in gram plant−1)

| DAP | CON | TDM | HEX | F ratio | LSD | Group comparison |

| Stem fresh weight | ||||||

| 40 | 35.08 | 36.52 | 36.57 | NS | 2.46 | |

| 80 | 128.16 | 133.15 | 127.54 | NS | 8.12 | |

| 120 | 580.34 | 582.42 | 558.63 | * | 15.64 | |

| 160 | 820.04 | 796.50 | 787.71 | ** | 27.52 | |

| 200 | 1500.36 | 1454.30 | 1382.28 | ** | 29.86 | CON TDM HEX |

| 240 | 2120.61 | 1967.29 | 1897.94 | ** | 34.81 | CON TDM HEX |

| Leaf fresh weight | ||||||

| 40 | 18.17 | 16.29 | 14.97 | NS | 3.65 | |

| 80 | 108.48 | 94.99 | 90.71 | ** | 4.12 | |

| 120 | 283.84 | 242.68 | 227.13 | ** | 8.56 | CON TDM HEX |

| 160 | 480.64 | 401.47 | 376.01 | ** | 16.24 | CON TDM HEX |

| 200 | 880.28 | 719.55 | 672.81 | ** | 24.56 | CON TDM HEX |

| 240 | 987.30 | 781.16 | 748.51 | ** | 28.42 | CON TDM HEX |

| Tuber fresh weight | ||||||

| 80 | 230.20 | 275.14 | 265.74 | * | 8.46 | |

| 120 | 1105.76 | 1362.29 | 1320.49 | ** | 26.48 | |

| 160 | 1900.71 | 2389.76 | 2351.55 | ** | 30.56 | |

| 200 | 2150.18 | 2753.30 | 2741.69 | ** | 31.85 | |

| 240 | 2640.44 | 3489.86 | 3448.15 | ** | 42.12 |

The total stem DW (Table 3) decreased with triazole treatments. HEX treatment inhibited the DW accumulation in the stems of cassava when compared to TDM treatment, and it was 94.28 POC on 240 DAP. TDM-treated plants also showed a decrease in stem DW, and it was 96.77 POC on 240 DAP. Triazole treatment caused a decrease in total DW in the leaf of cassava when compared to control. Among the triazole treatments, HEX-treated plants showed a decreased DW of the leaf, and it was 81.53 and 83.36 POC in HEX- and TDM-treated plants on 240 DAP. Triazole treatment marginally increased the total root DW (Table 3) when compared to control. Among the triazoles, TDM increased the root DW when compared to HEX, and it was 108.81 and 102.74 POC on 240 DAP. M. esculenta plants subjected to triazole treatments showed an increased total tuber DW when compared to control. The total tuber DW (Table 3) was increased with the age, and the increase rate was very high during the tuber maturation stage. The triazole compounds TDM and HEX increased the total tuber DW when compared to control plants. TDM increased the total tuber DW to 134.12 POC and in HEX it was 130.17 POC on 240 DAP.

Triazole-induced changes in the dry weight of cassava (values are the mean of seven replicates expressed in gram plant−1)

| DAP | CON | TDM | HEX | F ratio | LSD | Group comparison |

| Stem dry weight | ||||||

| 40 | 7.71 | 9.85 | 9.44 | * | 0.91 | |

| 80 | 24.64 | 28.17 | 26.21 | * | 1.68 | |

| 120 | 98.86 | 110.23 | 102.44 | ** | 3.64 | |

| 160 | 164.72 | 176.86 | 163.14 | ** | 4.65 | |

| 200 | 308.62 | 301.70 | 298.62 | ** | 4.42 | |

| 240 | 422.34 | 408.69 | 398.18 | ** | 5.78 | CON TDM HEX |

| Leaf dry weight | ||||||

| 40 | 3.84 | 3.57 | 3.47 | NS | 0.42 | |

| 80 | 19.10 | 16.51 | 16.27 | ** | 0.98 | CON T |

| 120 | 48.24 | 43.03 | 41.99 | ** | 1.81 | CON T |

| 160 | 81.44 | 70.05 | 69.87 | ** | 2.62 | CON T |

| 200 | 132.44 | 112.89 | 109.96 | ** | 2.16 | CON T |

| 240 | 153.22 | 127.72 | 124.92 | ** | 3.05 | CON T |

| Tuber dry weight | ||||||

| 80 | 43.38 | 52.39 | 51.318 | * | 1.06 | CON T |

| 120 | 182.86 | 224.16 | 220.62 | ** | 3.42 | CON T |

| 160 | 320.29 | 408.23 | 395.65 | ** | 5.12 | CON TDM HEX |

| 200 | 600.80 | 766.86 | 759.17 | ** | 8.36 | CON T |

| 240 | 780.42 | 1046.69 | 1015.87 | ** | 12.50 | CON TDM HEX |

The growth-retarding effect of triazole is caused by the inhibition of GA biosynthesis and increased ABA content [24]. Inhibition of leaf growth induced by increased ABA and lowered GA may be the cause for reduced leaf fresh weight. The total FW of the root increased significantly in both triazole-treated plants. Inhibition of gibberellin biosynthesis and increase in cytokinin content induced by triazoles [26] may be a reason for increased root growth in the triazole-treated cassava plants.

Exogenously applied gibberellin promoted stolon elongation and inhibited tuber formation, whereas exogenous ABA stimulated tuberisation and reduced stolon length in potato by counteracting the gibberellin action [27]. In tuber crops like radish, triazoles increased the partitioning of assimilates to the economically important plant part such as roots or tubers, and thus indirectly improved the yield per unit land [5]. Inhibited gibberellin biosynthesis and increased cytokinin and ABA content induced by these triazoles might be the cause of increased tuber growth in cassava.

Triazoles reduce the cell number, length, and width of the xylem cells [5]. Triazole induced a marked reduction in stem DW, and this may be attributed to the reduced GA level by triazole treatment. The stimulation of root growth may be related to the increased partitioning of assimilates towards the roots due to decreased demand in the shoot [28]. Lowered levels of GA are a pre-requisite for tuber formation. The mode of action of triazole in relation to early tuber development can be explained by the inhibitory effect of triazoles on GA [25]. Triazole increased the ability of partitioning of assimilates to tuberous organs as observed in gladiolus [29]. The alteration of the hormonal status in cassava induced by these triazoles might be responsible for the increased tuber DW.

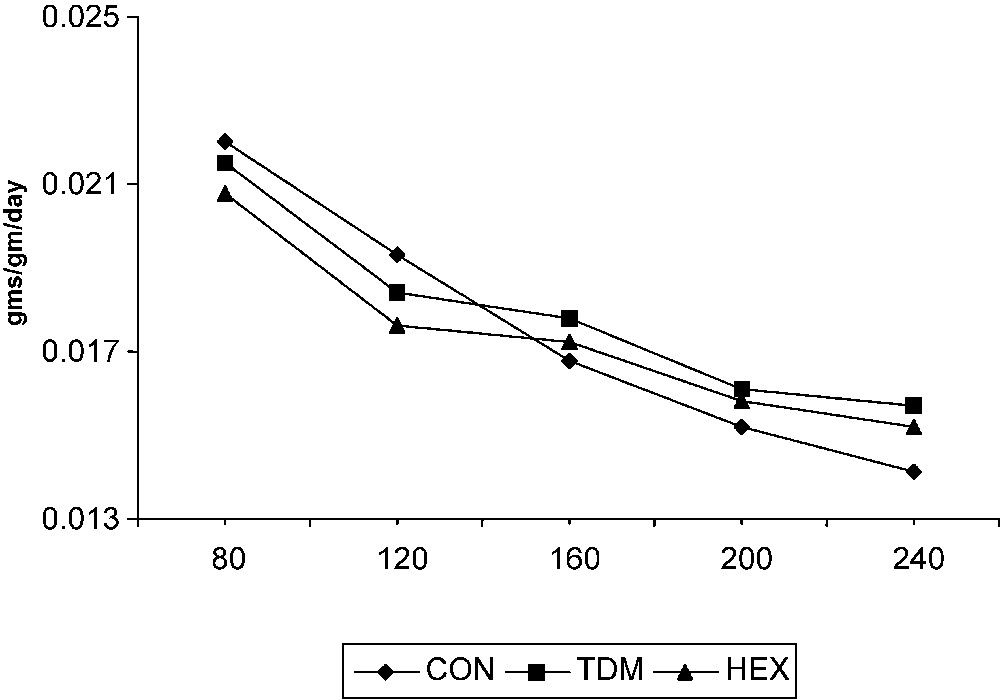

3.1.5 Effect of TDM and HEX on relative growth rate

The RGR of cassava was high at 80 DAP; later it declined gradually in the control and treated plants (Fig. 4). Triazole compounds increased the RGR of cassava after 200 DAP, i.e. the phase of tuber enlargement. Among the triazole treatments, there is no significant variation in RGR. However, the triazole-treated plants showed a high growth rate at later stages of growth (i.e. during tuber maturation) compared to control.

Triazole-induced changes in the relative growth rate (RGR) of cassava. Values are given as a mean of seven experiments in each group.

3.1.6 Effect of TDM and HEX on net assimilation rate

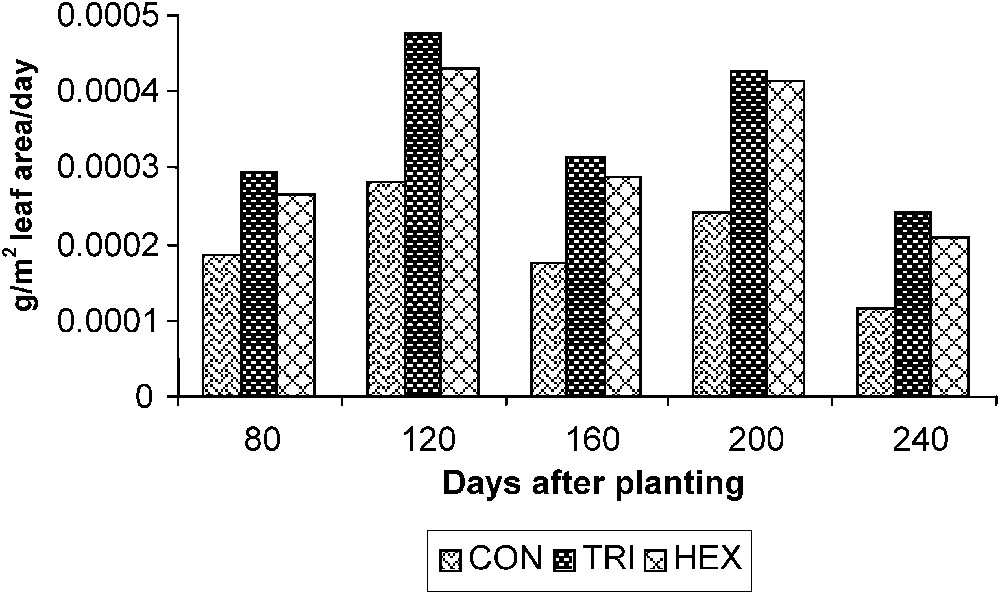

The NAR that correlates DW gain with leaf area in turn reflects the assimilation efficiency of the plant. Plants treated with TDM showed a higher photosynthetic efficiency, which is followed by HEX and control plants. The assimilation rate was high during the early period of growth, and it was gradually declined on 240 DAP in controls. However, the triazole-treated plants showed a sudden increase in the NAR between 120 and 200 DAP (Fig. 5).

Triazole-induced changes in the net assimilation rate (NAR) of cassava. Values are given as a mean of seven experiments in each group.

3.2 Effect of TDM and HEX on carbohydrate contents

3.2.1 Effect of TDM and HEX on starch content

In the leaves of cassava, the starch content increased with the age in the control and treated plants (Table 4). There was a marginal increase in the starch content of the leaves of triazole-treated plants when compared to control. Among the triazoles, TDM- and HEX-treated plants showed 112.09 and 110.67% starch content when compared to control on 240 DAP. Starch content of the tuber significantly increased with the age of the plant. In the triazole-treated plants, the starch content in the tuber increased to a higher level when compared to control. This trend was observed from the tuber initiation to maturation. Both the treatments showed a significant increased starch content in the tubers, and it was 21.05 and 18.76% higher than the control on 240 DAP.

Triazole-induced changes in the starch content in the leaves and tuber of cassava (values are the mean of three replicates, expressed in mg g−1 dry weight)

| DAP | CON | TDM | HEX | F ratio | LSD | Group comparison |

| Leaf | ||||||

| 40 | 10.14 | 11.02 | 11.01 | NS | 0.68 | |

| 80 | 12.17 | 13.21 | 13.06 | NS | 0.91 | |

| 120 | 14.68 | 16.16 | 16.06 | * | 1.08 | CON |

| 160 | 17.70 | 19.71 | 19.59 | * | 1.12 | CON |

| 200 | 18.31 | 20.63 | 20.14 | ** | 0.96 | CON |

| 240 | 19.68 | 22.06 | 21.78 | ** | 1.24 | CON |

| Tuber | ||||||

| 80 | 206.42 | 229.74 | 223.88 | ** | 4.65 | CON HEX TDM |

| 120 | 313.98 | 353.60 | 348.70 | ** | 4.14 | CON HEX TDM |

| 160 | 376.68 | 431.33 | 424.06 | ** | 5.60 | CON TDM HEX |

| 200 | 617.60 | 732.72 | 718.33 | ** | 7.46 | CON TDM HEX |

| 240 | 717.68 | 868.75 | 852.31 | ** | 7.14 | CON TDM HEX |

The increased starch content may also be due to decrease starch hydrolysis, as reported in bean [30]. Triazole compounds are known to alter the carbohydrate status in plants like sweet orange [31]. TDM inhibited the GA biosynthesis and increased the cytokinin level. The decreased gibberellin and increased cytokinin status induced by triazoles [32] might be the reason for increased tuber growth, starch content, and DW in the tubers of cassava.

3.2.2 Effect of TDM and HEX on sugar content

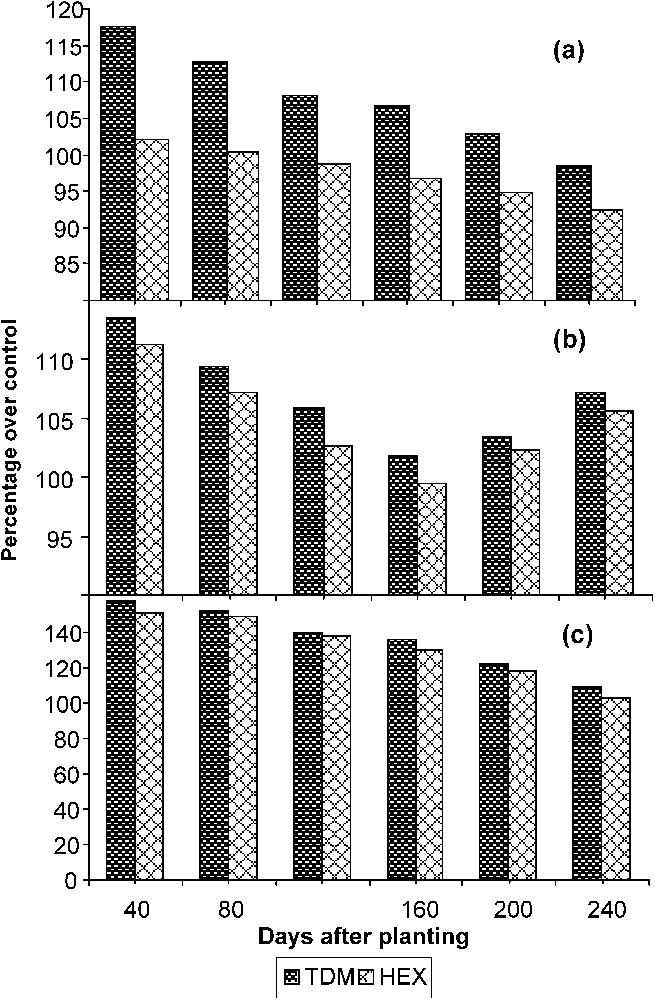

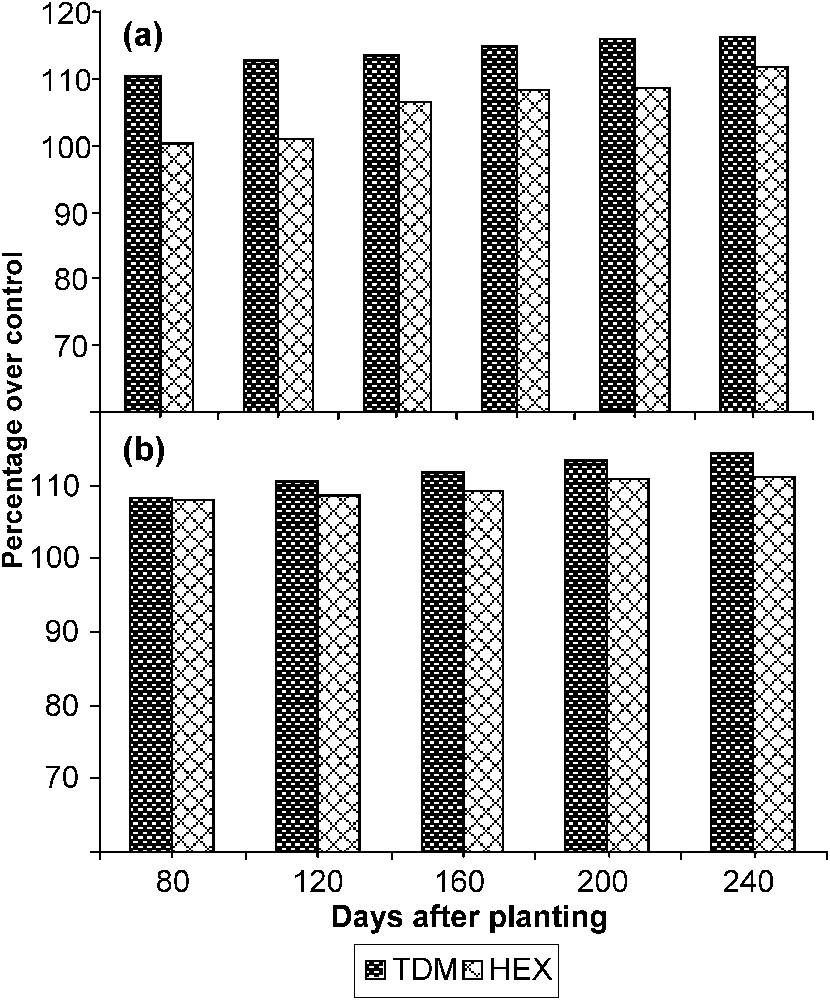

The total sugar content (Fig. 6) of the leaves increased with the age in the control and treated plants. TDM and HEX treatments caused an increase in sugar content at all stages of growth when compared to control and it was 116.29 and 111.54 POC respectively on 240 DAP. The total sugar content of the tuber significantly increased in both triazole treatments when compared to control. TDM and HEX increased the sugar content of the tuber to 114.18 and 111.24 POC respectively on 240 DAP. GA and kinetin treatment increased the reducing sugar content in the chickpea seedlings [33]. Triazole inhibited the gibberellin biosynthesis while increasing the cytokinins. The increased cytokinin content induced by the TDM and HEX might have increased the sugar content in leaf and tuber of cassava.

Triazole-induced changes in the sugar content in (a) the leaves and (b) the tuber of cassava. Values are given as a percentage over control.

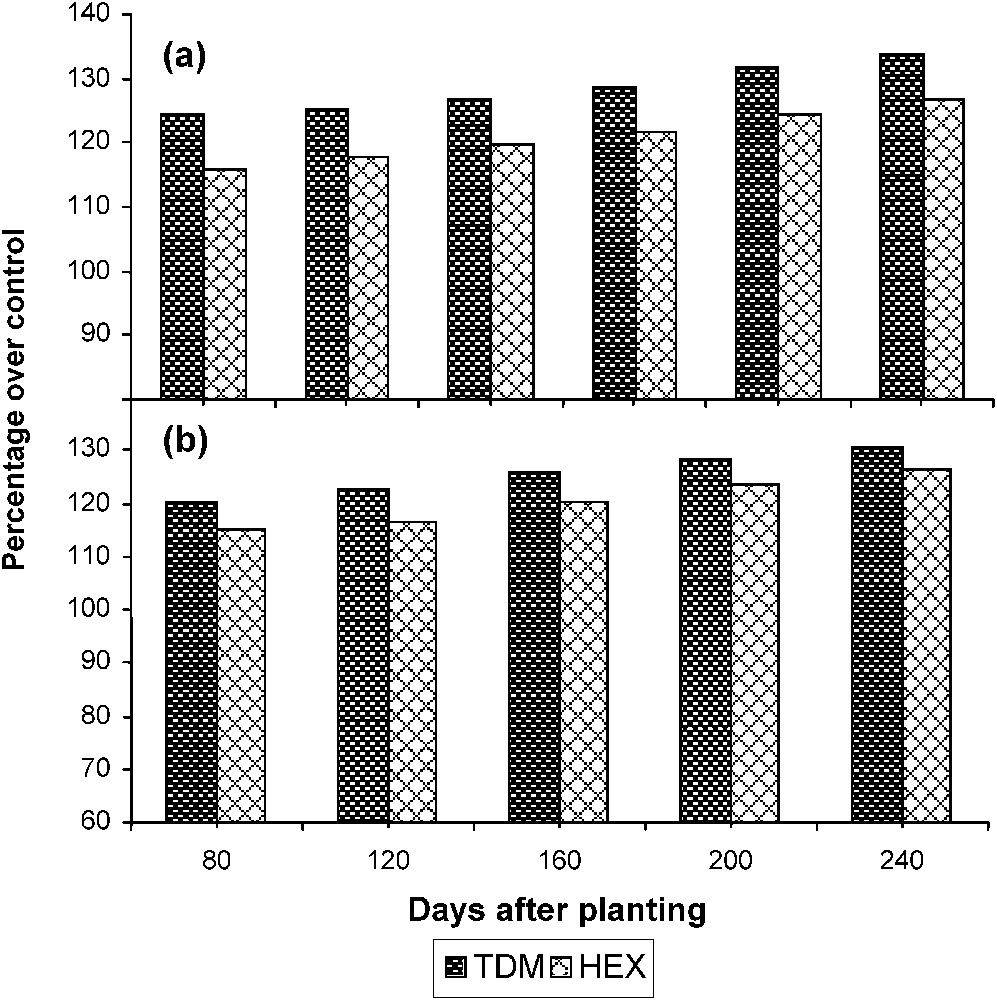

3.2.3 Effect of TDM and HEX on sucrose content

Triazole treatments increased the sucrose content of the leaves significantly when compared to control (Fig. 7). TDM increased the sucrose content to a higher level when compared to HEX and it was 133.79 and 126.76 POC respectively on 240 DAP. The sucrose content of the leaf was low at the early stages of growth but it increased to a higher level during the stage of tuber initiation to tuber maturation. The sucrose content of the tuber increased gradually from the stage of tuber initiation to maturation in the control and treated plants. Triazole treatments increased the sucrose content of the tuber tissue to a higher level as compared to control. TDM and HEX treatments increased the sucrose content of the tubers to 130.43 and 126.22 POC respectively on 240 DAP.

Triazole-induced changes in the sucrose content in (a) the leaves and (b) the tuber of cassava. Values are given as a percentage over control.

The requirement for a higher level of sucrose for successful tuber induction in in-vitro systems suggests that sucrose may play a role in the tuber-induction process [34]. The reduced amount of carbohydrate availability leads to the reduced development of sink organs of the plant [35]. Sucrose evidently plays a dual role in tuberisation, first as a signal for tuber inhibition and later as a nourishing substrate for growth. S-3307 (a triazole compound) increased the activity of acid invertase in cotton [36]. Even the low concentration of ABA increases the rate of sucrose efflux from the phloem tissue. The triazole compounds induced a raise in ABA content in many plants, and this increased ABA might have induced a sucrose efflux from the phloem of the tuber of cassava.

3.3 Effect of TDM and HEX on carbohydrate metabolising enzymes

3.3.1 Effect of TDM and HEX on starch phosphorylase activity

In the leaves of cassava, the activity of the enzyme SP increased with the age of the plant and gradually up to 200 DAP; later it declined in control and treated plants (Table 5). Both TDM and HEX increased the activity of the enzyme to a higher level and it was 26.47 and 23.73% higher than for controls in the treated plants on 200 DAP. In the cassava tuber, the enzyme SP activity gradually increased with the age in control and treated plants up to 200 DAP; later it declined in control and treated plants. Both triazole treatments increased enzyme activity at all growth stages, and it was a significantly higher level than for controls at all stages of tuber formation and maturation. In pea cotyledons, the SP level was higher in developing seeds, which accumulate starch, than in germinating seeds, where starch is mobilised [37].

Triazole-induced changes in the starch phosphorylase activity in the leaves and tuber of cassava (values are the mean of three replicates expressed in units mg−1 protein)

| DAP | CON | TDM | HEX | F ratio | LSD | Group comparison |

| Leaf | ||||||

| 40 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.41 | * | 0.010 | CON |

| 80 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.45 | * | 0.013 | CON HEX TDM |

| 120 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.54 | ** | 0.016 | CON TDM HEX |

| 160 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 0.65 | ** | 0.018 | |

| 200 | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.73 | * | 0.021 | CON |

| 240 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.28 | * | 0.024 | CON |

| Tuber | ||||||

| 80 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.44 | NS | 0.012 | CON |

| 120 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.51 | NS | 0.016 | CON |

| 160 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.53 | * | 0.014 | CON |

| 200 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.60 | * | 0.019 | CON |

| 240 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.28 | * | 0.021 | CON |

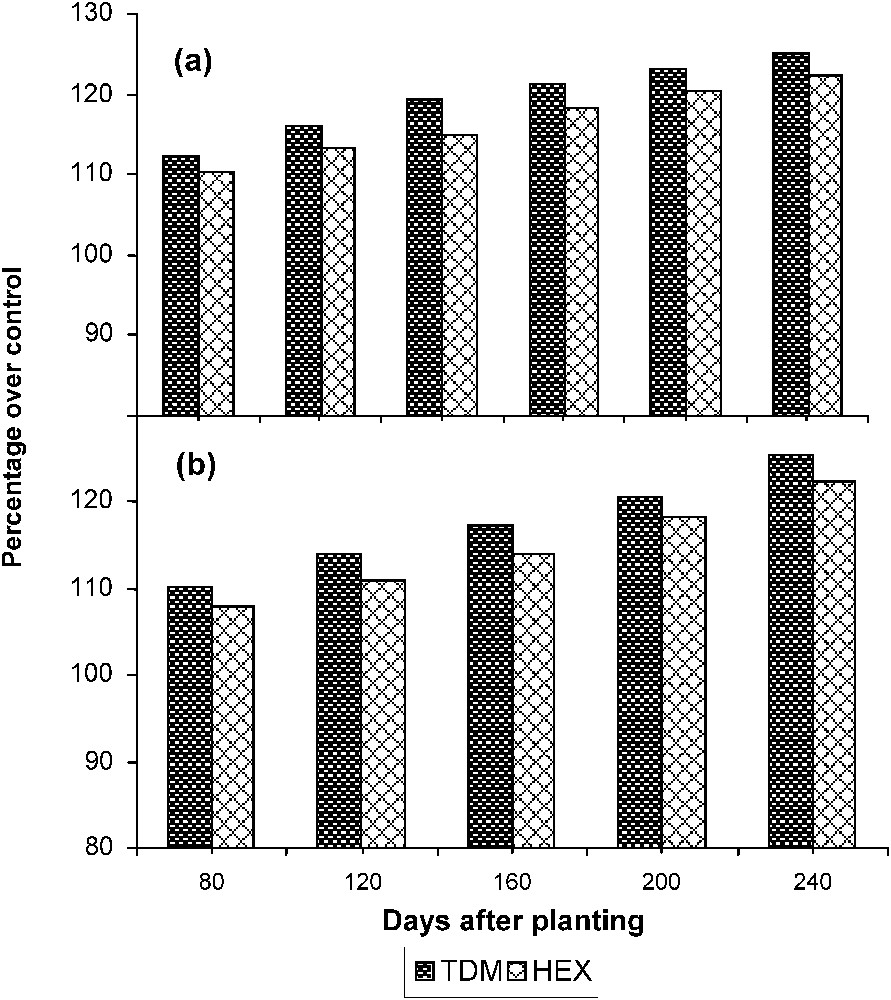

3.3.2 Effect of TDM and HEX on invertase activity

The activity of the enzyme invertase increased with the age in the leaves of control and treated cassava plants (Fig. 8). TDM and HEX treatments increased the invertase activity in the leaves largely, and it was 142.41 and 138.52 POC respectively on 240 DAP. Increased level of invertase activity was observed in the tuber of cassava at all stages of growth in control and treated plants. The increased enzyme activity in TDM- and HEX-treated plants was 32.52 and 30.14% higher than in controls in tubers on 240 DAP.

Triazole-induced changes in the invertase activity in (a) the leaves and (b) the tuber of cassava. Values are given as a percentage over control.

Invertase that is ionically bound to the cell wall irreversibly hydrolyses the transport sugar sucrose. The hexose monomers produced are taken up by sink cells through monosaccharide transporters [38]. Kinetin was shown to act mainly on tuber initiation where auxin predominantly intensified tuber growth, resulting in the production of larger tubers [39]. Invertases may also be involved in the long distance transport of sucrose by generating the necessary sucrose concentration gradient between sites of phloem loading and unloading [40]. The increased cytokinin content induced by the triazole compounds also might have increased the invertase activity in the leaves and tubers of cassava. An increase in starch and sugar content and DW of the tubers of cassava due to triazole treatments can be well correlated with the increased invertase activity in the tubers of triazole-treated plants.

3.3.3 Effect of TDM and HEX on sucrose synthase activity

The activity of SS (Fig. 9) significantly increased in the leaves of triazole-treated plants when compared to control. TDM and HEX increased the SS activity to a higher level than control, and it was 125.21 and 122.32 POC, respectively, on 240 DAP. The enzyme SS′ activity increased with the age in the tubers of control and treated plants. Triazole treatment increased the SS activity to a higher level when compared to control, and it was 25.44 and 23.32 POC on 240 DAP.

Triazole-induced changes in the sucrose synthase activity in (a) the leaves and (b) the tuber of cassava. Values are given as a percentage over control.

The major role of SS during the active growth phase is splicing sucrose moiety and providing a basic precursor for growth and building up of the sink structure [41]. Sucrose degradation is the first step for carbon utilisation by plant cells [42]. SS may regulate sucrose degradation and thus the rate of dry matter accumulation. The cleavage of sucrose by SS in the cytosol provides the substrate for starch synthesis, which is essential to increase the rate of dry matter import, as observed in tomato fruit [43]. Dramatic reduction in the extent of starch accumulation, protein content, and DW of transgenic SS-deficient potato tuber confirms that this enzyme is essential for effective sucrose metabolism in the developing tuber [44].

From the results of this investigation, it can be concluded that the application of TDM and HEX could well be used as a potential tool to manipulate carbohydrate metabolism and thereby the tuber quality as well as quantity in tuber crops like M. esculenta.