1 Introduction

Much attention in conservation biology is directed towards prestigious large-scale ecosystems, neglecting small-scale ones, such as pools. A simple research on Internet shows that scientific papers related to temporary pools represent less than 0.2% of the international literature dealing with wetlands, with only 26 papers published in 2007 (among which only 2 concern plants). For comparison, within the same year, peatlands constituted the main topic for 206 papers, estuaries 1642, lakes 5298 and rivers 10 420. However, despite this low scientific interest (proportional to their small geographic extent), pools strongly contribute to regional biodiversity because of their high β-diversity [1,2]. This is notably verified in the case of Mediterranean temporary pools, particularly rich in species [3–5], which harbour remarkable biological communities adapted to highly variable hydrological regimes [6]. Although often man-constructed, Mediterranean temporary pools are highly vulnerable to human activities, especially through agricultural intensification and inadequate management [7–9]. In spite of a better perception of wetlands within the last years, they often are ignored and their ecology misunderstood, sometimes resulting in non-intentional destructions [5].

A recent botanical survey of northern Algero–Tunisian acidic seasonal wetlands led to the discovery of a number of rare species including several Charophytes and two plants new to Tunisia, Pilularia minuta and Crassula vaillantii [10,11]. These findings highlight the lack of knowledge concerning North African temporary pools, which are still inhabited by a significant part of the endangered flora of the Mediterranean basin [4].

The present work focuses on the small pillwort (Pilularia minuta Durieu, Marsileaceae), a steno-Mediterranean endemic and one of the most emblematic species of Mediterranean temporary pools. The newly discovered populations in Mogods and Kroumiria regions (Tunisia) and in the El Kala National Park (Algeria) constitute an extension eastward of its North African distribution area. This amphibious Pteridophyte is classified as endangered at the scale of the Mediterranean, as critically endangered at the scale of North Africa (IUCN, unpublished data), as vulnerable/endangered on the red lists of France, Greece, Balearics, Spain, Italy and Morocco [5,12–15], and as a strictly protected species according to the Bern Convention.

We compare new phytosociological relevés to previous ones from Algeria and Tunisia [3,16–22], with the aim of characterising the plant communities of temporary pools of the Sejenane region (northern Tunisia) and assessing the ecological role of Pilularia minuta within Algero-Tunisian ponds. In addition, a chorological study at the Mediterranean scale allows discussing its capacity of dispersion and colonisation, the longevity of its populations and the impact of human-induced disturbances. At the regional scale, the recent discovery of new populations in Tunisia and north-eastern Algeria, in zones previously investigated [22–24], raises questions about our perception of the actual abundance of such a species, which could be biased by the rarity of its habitat, by the lack of scientific investigations and by life traits (dwarfism, sporadicity, ephemeral development [25,26]) likely to prevent its observation.

2 The Sejenane region

2.1 Geographical setting

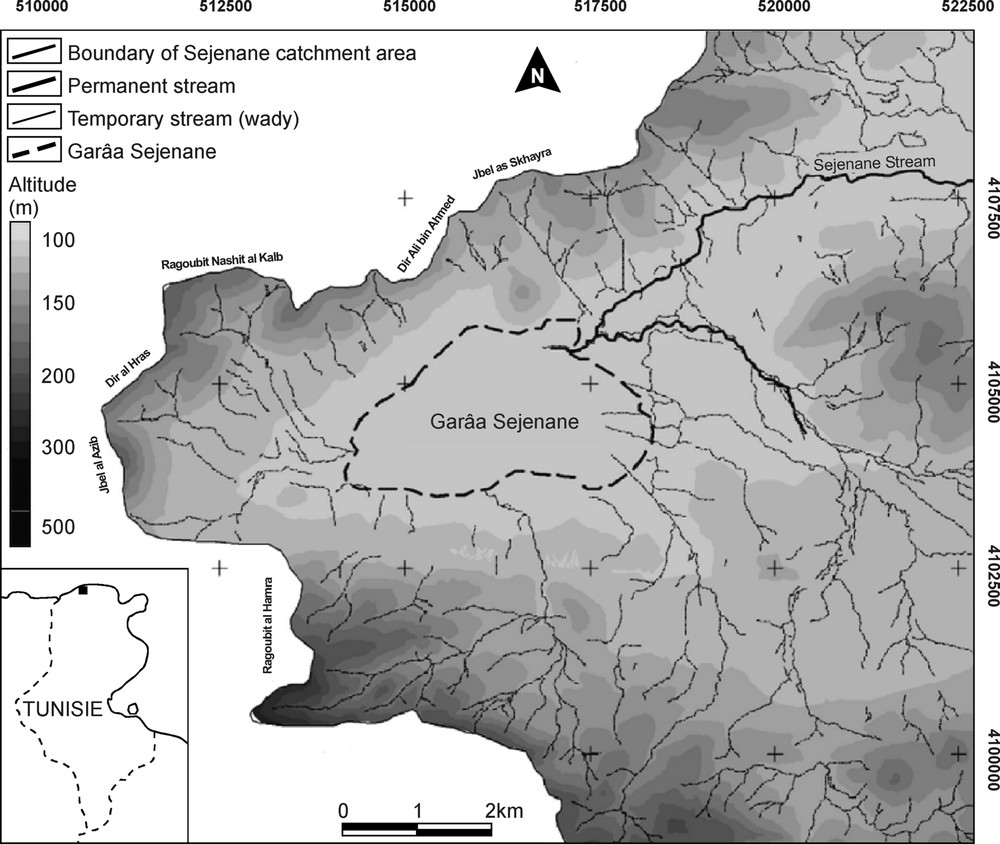

The present study was conducted in the region of Sejenane, in the Mogods Hills (northern Tunisia), at the eastern boundary of the region Kabylia–Numidia–Kroumiria, recently shown to constitute a major hotspot of plant diversity within the Mediterranean basin [27]. Garâa Sejenane is a vast plain measuring 5 km from east to west and 3 km from north to south (Fig. 1; 37°05′ N, 09°12′ E, 110 m a.s.l., i.e. above sea level). Similarly to a series of depressions occupying downstream the valley of Wadi Sejenane, Garâa Sejenane results from the subsidence of a Tertiary structure until the late Quaternary and from its gradual infilling by silici-clastic deposits. The soils of the depression are hydromorphic, and essentially composed of siliceous sands, silts and clays originating from small peripheral wades [23]. Garâa Sejenane is surrounded by eroded hills consisting of numulitic sandstone and culminating around 400 m a.s.l. These hills support degraded sclerophyllous forests constituted of Quercus suber, Myrtus communis, Pistacia lentiscus and Cistus spp. The mean annual precipitation is comprised between 600 and 900 mm in the plains and attains 1200 mm on the surrounding hills [28].

Location of Garâa Sejenane and topography of its catchment area (modified from the topographic maps of Oued Sejenane, Nefza, Hédhil and Cap Négro; 1/25 000, from TCO, Tunisia).

Garâa Sejenane has been previously described as a vast temporary wetland occupying the three-quarters of the plain, which centre was covered by a marsh of Schoenoplectus lacustris developed in 1 m-depth water [23,29]. The cutting of several drainage ditches resulted in the lowering of the water level, which at present does not exceed 50 cm in the deepest zones, and in the fragmentation of the marsh in a number of small depressions. Garâa Sejenane thus appears today as a mosaic of cultivated-pastured lands and shallow temporary pools. In the surroundings of the plain, there are some artificial water bodies resulting from sand and clay extraction by local people.

2.2 Materials and methods

Ten phytosociological relevés were performed in spring 2007 in various temporary habitats in and around Garâa Sejenane: in the central part of six pools (T1-6), on drier margins of two pools (T2m-3m), on a small wadi within a cork oak forest (T7) and on the edge of a semi-permanent lake (T8) (Table 1). These 10 phytosociological relevés are compared to 52 others from Tunisia and Algeria (Table 1; see also Appendix S1 in the Supplementary Material), by the way of a correspondence analysis, using the STATOS program [30]. The analysis was performed on the abundances of 63 selected species, presenting more than 3 occurrences. In order to focus on the relationships between hydrophilous species, the species invasive from surrounding dry zones (agricultural fields and cork oak forest) were excluded. Plant nomenclature follows Le Floc'h and Boulos [31] and syntaxonomical nomenclature follows Braun-Blanquet [3], de Foucault [32] and Molina [33].

Temporary pools from Algeria (A) and Tunisia (T) used in this study. Asterisks indicate relevés harbouring Pilularia minuta. SR: species richness; n.a.: not available.

| Code | Site | Alt (m) | Lat N | Long E | SR | Dominant species | Reference | |

| ∗ | T1 | Maachar1 | 110 | 37°05′10″ | 09°12′27″ | 50 | Isoetes velata, Myosotis debilis | This study |

| ∗ | T2 | Maachar2 – Centre | 110 | 37°05′07″ | 09°12′25″ | 15 | Pilularia minuta, Eleocharis palustris | This study |

| T2m | Maachar2 – Margin | 110 | 37°05′07″ | 09°12′25″ | 37 | Isoetes histrix, Crassula tillaea | This study | |

| ∗ | T3 | Guetma – Centre | 110 | 37°07′37″ | 09°15′59″ | 27 | Eleocharis palustris, Lythrum borysthenicum | This study |

| T3m | Guetma – Margin | 110 | 37°07′37″ | 09°15′59″ | 42 | Isoetes histrix, Isolepis cernua | This study | |

| ∗ | T4 | Grande Garâa1 | 110 | 37°05′12″ | 09°11′57″ | 22 | Elatine macropoda, Lythrum hyssopifolia | This study |

| ∗ | T5 | Grande Garâa2 | 110 | 37°05′09″ | 09°11′55″ | 22 | Elatine macropoda, Myosotis debilis | This study |

| ∗ | T6 | Grande Garâa3 | 110 | 37°04′57″ | 09°11′50″ | 33 | Isoetes velata, Lythrum borysthenicum | This study |

| T7 | Msaddar | 110 | 37°04′41″ | 09°09′00″ | 39 | Isoetes histrix, Solenopsis laurentia | This study | |

| T8 | Majen Chitane lake | 150 | 37°09′10″ | 09°05′54″ | 21 | Isoetes velata, Isolepis cernua | This study | |

| TV1 | Majen Chitane lake | 150 | 37°09′10″ | 09°05′54″ | 22 | Isoetes velata, Myosotis debilis | [16] | |

| TV2 | Majen Choucha | 115 | 37°00′38″ | 09°12′43″ | 22 | Isoetes velata, Lythrum borysthenicum | [16] | |

| TV3 | Majen el Ma – Centre | 505 | 36°46′52″ | 08°47′24″ | 8 | Isoetes velata, Apium crassipes | [16] | |

| TH1 | Majen el Ma – Margin | 505 | 36°46′52″ | 08°47′24″ | 29 | Isoetes histrix, Radiola linoides | [16] | |

| TV4 | Sraï el Majen – Centre | 931 | 36°33′19″ | 08°20′17″ | 10 | Isoetes velata, Ranunculus ophioglossifolius | [16] | |

| TH2 | Sraï el Majen – Margin | 931 | 36°33′19″ | 08°20′17″ | 21 | Isoetes histrix, Ranunculus ophioglossifolius | [16] | |

| TH3 | Meloula | 150 | n.a. | n.a. | 23 | Juncus capitatus, Isoetes histrix | [3] | |

| ∗ | A1 | Msabia1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 21 | Pilularia minuta, Ranunculus baudotii | [18] |

| ∗ | A2 | Msabia2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 18 | Isoetes velata, Pilularia minuta | [18] |

| ∗ | A3 | Gauthier1 | 28 | 36°50′14″ | 08°26′33″ | 16 | Isoetes velata, Pilularia minuta | This study |

| AH1 | Réghaïa5 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 21 | Isoetes histrix, Lotus angustissimus | [20] | |

| AH2 | Réghaïa6 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 20 | Isoetes histrix, Crassula tillaea | [20] | |

| AH3 | Réghaïa7 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 17 | Isoetes histrix, Lotus angustissimus | [20] | |

| AH4 | Réghaïa8 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 14 | Isoetes histrix, Juncus pygmaeus | [20] | |

| AH5 | Réghaïa9 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 10 | Isoetes histrix, Radiola linoides | [20] | |

| AH6 | Zariffet | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 13 | Isoetes histrix, Radiola linoides | [20] | |

| AH7 | Akfadou1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 16 | Isoetes histrix, Radiola linoides | [20] | |

| AH8 | Akfadou2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 24 | Isoetes histrix, Radiola linoides | [20] | |

| AH9 | El Milia | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 12 | Isoetes histrix, Cicendia filiformis | [20] | |

| AH10 | Petite Rassauta4 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 10 | Isoetes histrix, Ophioglossum lusitanicum | [20] | |

| AH11 | Sidi Bernous1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 10 | Isoetes duriei, Juncus capitatus | [20] | |

| AH12 | Sidi Bernous2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 13 | Isoetes duriei, Juncus bufonius | [20] | |

| AH13 | Sidi Bernous3 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 10 | Isoetes duriei, Juncus bufonius | [20] | |

| AH14 | Jbel Bissa1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 7 | Isoetes duriei, Juncus pygmaeus | [20] | |

| AH15 | Jbel Bissa2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 8 | Isoetes duriei, Juncus pygmaeus | [20] | |

| AV1 | Réghaïa1 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 12 | Isoetes velata, Myosotis debilis | [20] | |

| AV2 | Réghaïa2 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 11 | Isoetes velata, Oenanthe fistulosa | [20] | |

| AV3 | Réghaïa3 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 17 | Isoetes velata, Lythrum thymifolium | [20] | |

| AV4 | Réghaïa4 | n.a. | 36°45′ | 03°23′ | 12 | Isoetes velata, Solenopsis laurentia | [20] | |

| AV5 | Ksila5 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 14 | Isoetes velata, Lythrum borysthenicum | [20] | |

| AV6 | Ksila1 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 13 | Isoetes velata, Myosotis debilis | [20] | |

| AV7 | Guelmane el Bastoul | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 13 | Isoetes velata, Myosotis debilis | [20] | |

| AV8 | Grande Rassauta | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 12 | Isoetes velata, Mauranthemum paludosum | [20] | |

| AV9 | Corso | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 9 | Isoetes velata, Lythrum hyssopifolia | [20] | |

| AV10 | Sidi Klifa | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 20 | Isoetes velata, Eryngium pusillum | [20] | |

| AV11 | Cap Sigli | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 16 | Isoetes velata, Eleocharis palustris | [20] | |

| AV12 | Petite Rassauta1 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 12 | Isoetes velata, Crassula vaillantii | [20] | |

| AV13 | Petite Rassauta2 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 16 | Isoetes velata, Elatine macropoda | [20] | |

| AV14 | Petite Rassauta3 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 13 | Lythrum hyssopifolia, Mauranthemum paludosum | [20] | |

| AV15 | Lac Mellah, El Kala5 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 16 | Isolepis cernua, Juncus pygmaeus | [21] | |

| AV16 | Lac Mellah, El Kala6 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 22 | Isolepis cernua, Juncus spp. | [21] | |

| AV17 | Lac Oubeira, El Kala10 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 13 | Isolepis cernua, Juncus tenageia | [21] | |

| AV18 | Lac Oubeira, El Kala11 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 12 | Isolepis cernua, Juncus bufonius | [21] | |

| AV19 | Bechna, Guerbes16 | 36°53′08″ | 07°17′80″ | 21 | Isoetes velata, Callitriche truncata | [22] | ||

| AV20 | Linaires, Guerbes17 | 36°52′ | 07°18′ | 8 | Isoetes velata, Cerinthe major | [22] | ||

| AR1 | Grande Rassauta1 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 15 | Isoetes velata, Mauranthemum paludosum | [19] | |

| AR2 | Rassauta2 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 12 | Isoetes velata, Lythrum tribracteatum | [19] | |

| AR12 | Rassauta12 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 16 | Mauranthemum paludosum, Lythrum tribracteatum | [19] | |

| AR20 | Rassauta20 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 24 | Mauranthemum paludosum, Lythrum hyssopifolia | [19] | |

| AR21 | Rassauta21 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 28 | Isoetes velata, Lythrum tribracteatum | [19] | |

| AR22 | Rassauta22 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 23 | Mauranthemum paludosum, Lythrum hyssopifolia | [19] | |

| AR23 | Rassauta23 | 25 | 36°44′ | 03°11′ | 20 | Mauranthemum paludosum, Coronopus squamatus | [19] |

2.3 Plant biodiversity of the temporary pools of the Sejenane region

The plant communities of the Sejenane region appear rich and diversified, still harbouring most of the species noted 70 and 50 years ago (see Appendix S1). Our investigations lead to discover 19 species not previously indicated at Garâa Sejenane [17,23,29,34–38], among which two plants new for Tunisia (Pilularia minuta and Crassula vaillantii). In addition, six species of Charophytes (Chara braunii, C. connivens, C. oedophylla, C. vulgaris, Nitella opaca and Tolypella glomerata) were identified. Except for the cosmopolitan Chara vulgaris, these taxa are remarkable among the flora of Tunisia. Three of them (Chara braunii, C. oedophylla and Nitella opaca), complete an earlier list of 21 taxa sensu microspecies provided by Corillion [39]. Chara braunii was found in submerged agricultural fields and other species were collected in artificial water bodies on clay substrate up to 2 m deep. Nitella opaca was observed alive for the first time in Tunisia. This confirms the presence of this species in northern Tunisia where it had been recorded previously only from subfossil oospores from the sediments of the coastal freshwater lake (Majen Chitane [40]). Chara oedophylla was originally described by Feldmann [41] based on unstudied herbarium specimens collected in Tunisia in 1927. The species had not been observed there since then. At Garâa Sejenane, it forms a monospecific population, a dense stand of ca. 5 m2, in one of the artificial pools. As stated by the original description by Feldmann [41], the typical features of C. oedophylla are disjoined gametangia (oogonia and antheridia located on separate nodes) and numerous swollen bract cells. Besides its type-locality, this very rare species has been recorded only in a single pool in Morocco (Corillion in [42]), in a few localities in Spain [43] and in two temporary lakes in southern France [44].

The major conservatory importance of Garâa Sejenane, already underlined by Pottier-Alapetite [23], is enhanced by the presence of species for which Garâa Sejenane is the only known locality in Tunisia (Mibora minima, Persicaria amphibia, Utricularia gibba, U. vulgaris, and the newly discovered Crassula vaillantii).

2.4 The temporary pool communities of Numidia

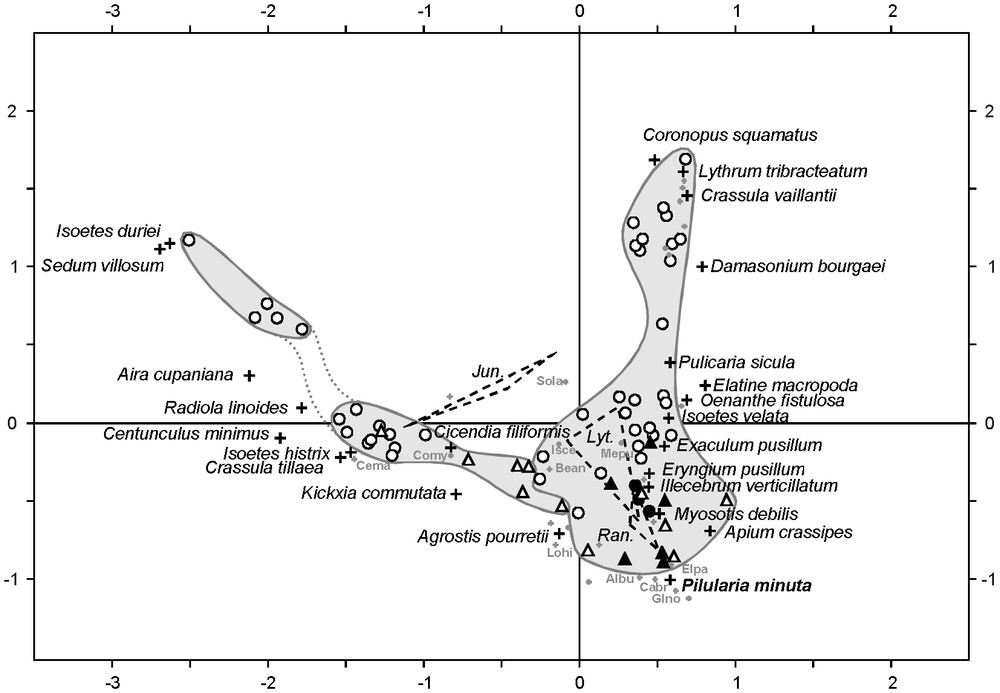

The scatterplot of multivariate analysis on Algero-Tunisian phytosociological relevés (Fig. 2) presents an horseshoe trend (Guttman effect), indicative for the partial interdependence of the two axes, both related to the predominant control of temporary-pool vegetation by hydrology [9]. Despite this distortion, the first axis distinguishes the two main communities of North African temporary habitats: the terrestrial community of Isoetes histrix and Radiola linoides, and the amphibious one of Isoetes velata and Myosotis debilis (= M. sicula). These communities correspond to the associations Isoeto histricis–Radioletum linoidis Chevassut & Quézel 1956 and Myosotido siculae–Isoetetum velatae Pottier-Alapetite 1952, respectively [33], and are included within the alliances Ophioglosso lusitanici–Isoetion histricis De Foucault 1988 and Antinorio agrostideae–Isoetion velatae De Foucault 1988, respectively [32].

Scatterplot of the correspondence analysis realised on phytosociological relevés from Algeria (circles) and Tunisia (triangles), comprising 62 sites (Table 1) and 63 taxa. Black elements correspond to relevés containing Pilularia minuta. Dashed lines link species of Juncus (J. bufonius, J. capitatus, J. pygmaeus), Lythrum (L. borysthenicum, L. hyssopifolia, L. thymifolium) and Ranunculus (R. ophioglossifolius, R. baudotii, R. sardous), respectively. The names of the most significant species (crosses) are given in extensive form. Other species are located by grey dots, with sometimes abbreviated names: Albu, Alopecurus bulbosus; Bean, Bellis annua; Cabr, Callitriche brutia; Cema, Centaurium maritimum; Comy, Coleostephus myconis; Elpa, Eleocharis palustris; Glno, Glyceria notata; Isce, Isolepis cernua; Lohi, Lotus hispidus; Mepu, Mentha pulegium; Sola, Solenopsis laurentia. Inertia percentages of axe 1 (horizontal) and axe 2 (vertical) are respectively 12.57 and 9.58.

The community of Isoetes histrix and Radiola linoides appears composed of two groups (Fig. 2), the first one corresponding to the typical association, and the second one to the sub-association Isoetetosum durieui Chevassut & Quézel 1956 [33]. On the opposite side, the I. velata community is more homogeneous and characterised by a rich assemblage including Exaculum pusillum, Apium crassipes, Illecebrum verticillatum, Lythrum spp., Myosotis debilis, Oenanthe fistulosa, Pilularia minuta, Pulicaria sicula and Ranunculus spp. Among the species occupying the extremity of the gradient, Elatine macropoda, Crassula vaillantii and Damasonium bourgaei were generally observed together, as well at the Rassauta [19] as at Garâa Sejenane. These species characterise the sub-association described by Chevassut and Quézel [20] as ‘sous-association à Elatine campilosperma (= E. macropoda)’.

The second axis of the biplot separates the Tunisian relevés from the Algerian ones, showing the greatest heterogeneity of the latter ones. That feature may be explained by two main elements. On the first hand, the higher richness of Tunisian relevés (Table 1; see Appendix S1) is probably related to a patchy development of both communities in Garâa Sejenane and in other Tunisian localities, which favours the constitution of mixed communities. Similar intermediate vegetation structures were reported from El Kala region, in northern Algeria, where Isoetes velata is associated with Isolepis cernua, Cicendia filiformis and Radiola linoides [21]. On the second hand, this geographical segregation is probably also induced by some species with reduced distribution areas. For instance, Apium crassipes is restricted in Maghreb to Tunisia and eastern Algeria, and Mauranthemum paludosum occurs only in Algerian relevés, and more especially in those from the Rassauta [19]. Such species exemplify the Tertiary and Pleistocene connexions between southern Europe and northern Africa through Siculo-Tunisian and Iberico-Moroccan bridges [45,46], and maybe also reveal modern connexions along water-bird migration routes.

2.5 Ecological significance of Pilularia minuta

The correspondence analysis (Fig. 2) allows assessing the ecological role of Pilularia minuta within Algero-Tunisian temporary pools. The few relevés in which it occurs are clearly affine with the Isoetetum velatae. This is consistent with Braun-Blanquet [3] who considers this species as a characteristic of the Isoetetum setacei Br.-Bl. 1936, the vicariant association from southern France, defined by the presence of Isoetes setacea and Lythrum borysthenicum. Nevertheless, it occurs on the correspondence analysis in an intermediate position between the I. velata community and the I. histrix one (Fig. 2), near stress-tolerant species sensu [47] (Agrostis pourretii, Eryngium pusillum, Ranunculus baudotii, R. sardous). This is consistent with our observations in Garâa Sejenane, where P. minuta develops in a great variety of situations, showing an unexpected dynamism. It effectively occurs as well on bare soils in overgrazed I. velata communities characterised by E. pusillum, as in wheel tracks and in alternatively inundated and cultivated zones together with Elatine macropoda, Damasonium bourgaei and Crassula vaillantii. The AFC and our field observations highlight the heliophilous pioneer character and the poor competitive ability of P. minuta, and suggest that it could benefit from open zones created by grazing and temporary extensive cultures. The apparent dynamism of the species during the survey period however could have also been triggered by favourable climatic conditions (a particularly rainy spring).

3 The Mediterranean basin

3.1 Materials and methods

The investigation at the scale of the Mediterranean basin are based on a survey of the available literature dealing with the distribution of Pilularia minuta [6,18,25,29,48–68] and of the specimens conserved in the Herbariums of Montpellier and Rabat, completed by numerous personal communications and by our own observations (Table 2; see Supplementary Material, Appendix S2).

Locations and dates of the last observations of Pilularia minuta.

| Country | No. | Region | Site | Population | Last observation | References |

| Tunisia | 1 | Mogods | Garâa Sejenane | >10 pools | 2006–2007 | This study |

| Kroumiria | Majen el Ma | 1 pool | 2009 | This study | ||

| Algeria | 2 | El Kala region | El Frîn (mares Gauthier) | >3 pools | 2008 | This study |

| 3 | Kabylies | – | Destroyed | 19th century? | [48] | |

| 4 | Alger region | Bou Ismaïl-Castiglione | Destroyed | 1854 | [29] | |

| 5 | Oran region | Djebel Santo, Mudjardjo, Les Issers, Msabia | Destroyed | 1952 | [48] | |

| Morocco | 6 | Coastal Meseta | Benslimane, south of Rommani | 7 pools | 2006 | This study |

| Mamora | Southeast of Tiflet, western Mamora | 3 pools | 2008 | This study | ||

| Gharb | Sidi Slimane | 1 pool | 2009 | This study | ||

| Portugal | 7 | Algarve | Vila do Obispo, Ribatejo, Baixo Alentejo | – | 2003–2006 | M. Porto |

| Spain | 8 | Andalusia | Cordóba, Sevilla and Huelva provinces | >10 pools | 2006–2007 | [49] |

| 9 | Castilla Léon | Zamora province | 1 pool | 2003–2006 | P. Bariego Hernández | |

| 10 | Minorca | Bassa Verda, Mola de Fornells, Es Armaris | 3 pools | 2009 | This study | |

| France | 11 | Hérault | Roquehaute, Montblanc | ca. 10 pools | 2007 | J. Molina |

| 12 | Maritime Alps | Biot | Destroyed | 1979 | [50] | |

| 13 | Corsica | Tre Padule de Suartone, Arasu, Frasseli, Padullelu… | ca. 12 pools | 2007 | L. Sorba | |

| Italy | 14 | Sardinia | Monte Minerva, Scanu Montiferru, Suni | 5 pools | 2007 | S. Bagella, M.C. Caria |

| 15 | Sardinia | Pula, Tempio | Destroyed | >30 years? | S. Bagella | |

| 16 | Sicily | – | – | >10 years? | [51] | |

| 17 | Lazio | Nettuno | Destroyed | 1903 | [52,53], S. Bagella | |

| Croatia | 18 | Mediterranean coast | Cres, Rab | 2 pools | 2002 | S. Brana |

| Greece | 19 | Aegean Sea | 2 islands (Psathoura) | 3 pools | 1980 | [54] |

| Turkey | 20 | Izmir (Smyrna) | Pagus mount | 1–3 pools | 2000 | [55], A.J. Byfield, G. Fitz |

| Cyprus | 21 | – | – | – | >10 years? | [6,56] |

3.2 Historical and geographical data

At the scale of the Mediterranean basin, the different and often contradictory chorological indications provided by floras from Europe and Mediterranean countries emphasize the weakness of the current knowledge concerning Pilularia minuta. For instance, the Med-Checklist [69] indicates its presence in Portugal, France (Hérault, Corsica), Italy (Sardinia, Sicily), Yugoslavia, Greece, Algeria and Morocco, but does not mention Spain, Italy or Turkey. The Flora of Spain [70] indicates, presumably erroneously (P. Bariego Hernández, pers. comm.), its presence in Catalonia; and the first Flora of Turkey [71] does not include it, while it is mentioned there by the most recent one [55]. The Flora of Portuguese Pteridophytes [72] and the Flore pratique du Maroc [73] present even erroneous pictures showing several fronds per nod. However, although providing incomplete records, literature and herbarium specimens inform about scientific investigations and Pilularia's space–time dynamics. They notably reveal that the explorations have been – and still are – highly heterogeneous, some geographical zones (e.g. eastern Mediterranean) having been less investigated than others.

3.3 Dispersion, longevity of populations and relation to disturbances

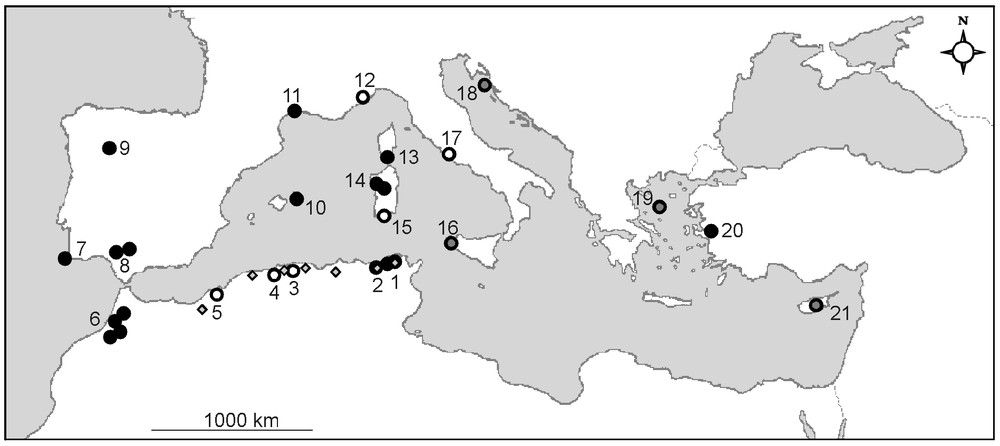

Since its discovery by De Notaris in 1835 in Sardinia, Pilularia minuta has been found in 20 other small, disconnected areas distributed around the Mediterranean basin (Fig. 3; Table 2). These findings [54,57–62,65] could translate new colonisations by the plant, as well as successful botanical explorations. In comparison with the regular observations of P. minuta since 1869 in Hérault, southern France (see Appendix S2), its recent discovery in several areas, such as Corsica (1964), Maritime Alps (1969), Balearics (1986), central Spain (1992), northern Tunisia (2006), north-western Sardinia (2007) and north-eastern Algeria (2008), may suggest new installations and consequently, good capacities of dispersion and colonisation.

Location of Pilularia minuta populations around the Mediterranean basin (modified and completed from [62]). Black dots indicate present-day populations (observation <10 years), grey dots indicate populations not confirmed recently (10–30 years), and white dots indicate populations destroyed or not confirmed for more than 30 years. Small dots in Algeria and Tunisia localise the phytosociological relevés. Numbers refer to Table 2.

The most investigated areas (northern Algeria, Andalusia, Hérault, western Morocco, Sardinia and Corsica) moreover offer opportunities for assessing the potential longevity of populations and the causes of their eventual collapse. Four of them still harbour today populations known for several decades: Andalusia, Spain and Hérault, France (ca. 140 years), western Morocco (ca. 80 years) and Corsica, France (ca. 40 years) [25,58,59,74] (see Appendix S2). These populations seem to be stable, despite a possible regression in Hérault attributed to the recent invasion of pools by perennial species [75]. In contrast, Algerian populations experienced more complex histories, with a number of sporadic observations and disappearances resulting essentially from destruction of pools for agriculture purpose [18,20,29,76]. Despite no observation was made since 1952 in the previously known areas, P. minuta was discovered in March 2008 in the El Kala National Park (N.E. Algeria) [11]. Despite the attested long-lasting maintenance of the populations of Andalusia, Hérault, Corsica and Morocco, the number of local extinctions, which concern about a quarter of the known populations (Table 2), reveals the sensitivity of the small pillwort to human-induced disturbances and, though a lesser extent, to plant competition.

4 Discussion

The obtained results, both at the Numidian scale (Fig. 2) and at the Mediterranean scale (Fig. 3), show that Pilularia minuta presents paradoxical biological and ecological traits, such as a competitive incompetence [77] but long-lasting populations, and possible good dispersion ability but weak local effectives. Its response to human activities appears ambivalent: disturbances apparently favour its development in Tunisia and maybe in Morocco, while they triggered its disappearance from Algeria and south-eastern France. All these features support the hypothesis of a sporadic behaviour, strongly dependent on climate conditions, human practices and perennial plant competition, and resulting in regular extinctions and colonisations. Despite the lack of quantitative data, the main dispersion vector of P. minuta could be animals, such as large herbivores at a local scale (L. Rhazi, personal observations) and migratory water-birds at the Mediterranean scale [5]. This would have important conservation implications, notably through the source-sink concept, linking the metapopulation stability within a patchy distribution to high dispersal rates or to the existence of extinction-resistant populations [78–80]. The latter feature is particularly likely to play a significant role for P. minuta, which seems to occur both in relatively stable systems of more than 10 pools (Andalusia, Corsica, Hérault, western Morocco and northern Tunisia) and in small and precarious systems of 1–3 pools (Maritime-Alps, Lazio, Minorca, Croatia, Psathoura, Cyprus, Izmir). In this context, the assessment of its rarity should only be based on the stable ‘source’ populations, which may presently be estimated at 6, among which the Corsican one was discovered less than fifty years ago [58], and the Tunisian one only two years ago. The regular observations reported from Andalusia, Corsica, Hérault and western Morocco (see Appendix S2) finally suggest that the natural sporadicity and the ephemeral character of the development of P. minuta are insufficient for explaining the weak number of large populations at the Mediterranean scale.

The abundance of botanical studies conducted on Mediterranean temporary pools is strongly heterogeneous and irregular (Table 2; see Appendix S2). Still today, numerous areas suffer from insufficient or even inexistent botanical investigations, as a result of isolation, political instability or lack of local specialists. These factors could for instance explain the apparent greater rarity of Pilularia minuta in eastern Mediterranean, and its surprising eclipse up to one century in Turkey [55]. This hypothesis however should be nuanced by biogeographical patterns: the decreasing abundance of Mediterranean temporary pools from west to east [5] could effectively contribute to explain the greater rarity of their flora in the eastern Mediterranean basin, as a result of their narrow niche width [81,82]. The recent discovery of Pilularia microspores in sediments of a northern Corsica temporary pool, in a region where it has never been observed (S.D. Muller, unpublished data), suggests that the lack of botanical survey could also explain its late discovery in Corsica [58]. These points probably reveal a significant influence of the heterogeneity of botanical investigation on the perception of the rarity of such a species. However, fragmentary data may not be the reason for its very recent discovery in Tunisia and northeastern Algeria, because the concerned sites had been well investigated earlier [22–24].

5 Conclusions

The compiled floristic data from Algeria and Tunisia concerning Pilularia minutia highlight the difficulty in establishing the actual abundance of such a dwarf, sporadic and ephemeral species. They moreover suggest a significant influence of these biological traits and of the lack of botanical investigations on the perception of its abundance, both at the regional scale and the Mediterranean scale. In particular, they lead to suspect an underestimation of its actual abundance, especially in the eastern Mediterranean basin (Balkans, Turkey, Cyprus). On the other hand, the small pillwort experienced for a century the extinction of a quarter of its known populations, mainly as a result of the anthropogenic general degradation of wetlands. This decline seems to have mainly affected small populations (Maritime-Alps, Lazio) and highly disturbed areas (Algeria), but not the largest populations such as those of Corsica, Hérault, Andalusia and western Morocco. Assessment of the conservation status and design of management policies for such a species should focus on those large and seemingly stable populations, which only could constitute ‘source populations’ likely to assure the permanence of the entire system [78–80].

In this metapopulation context, our results may reveal hope signs for conservation of Pilularia minuta, through a set of large and apparently stable populations, possibly associated to good capacities of dispersion and colonisation. Nevertheless, these large populations are very few and strongly dependent on human activities (agriculture, herding, urbanism and management), which appear to exert complex and paradoxical influences on this species in particular, and on seasonal pools in general [8]. These large populations should be urgently protected and rationally managed: the drainage of the shallow depressions where they develop would be particularly disastrous.

Our study finally points to the need for further investigations in order to improve the conservation of the rare plants of Mediterranean temporary pools as well as the development of ecological theory. It notably highlights the crucial lack of knowledge concerning the metapopulation functioning at the Mediterranean scale, which could be addressed through associated studies of genetics and palaeoecology. Such multidisciplinary studies should indeed lead to evidence the eventual connections (gene fluxes) between distant populations, and the historical factors which may also contribute to rarity [83–85].

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by Egide-CMCU (PHC Utique 07G0809) and Egide-CMIFM (PHC Volubilis MA/07/172). We thank Abelhamid Karem (Direction Générale des Forêts, Ministère de l'Agriculture et des Ressources hydrauliques de Tunisie) for fieldwork authorisations and facilities. The research benefited from invaluable information kindly provided by numerous Mediterranean scientists. We notably express our grateful thanks to Pedro Beja, Isabel Figueiral, Miguel Porto (Portugal), Antonio J. Delgado, Leopoldo Medina Domingo, Patricio Bariego Hernández (Spain), Henri Michaud, James Molina, Marie-Laurore Pozzo di Borgo, Guilhan Paradis, Laurent Sorba (France), Simonetta Bagella (Italy), Antun Alegro (Croatia), Serdar Gökhan Senol, Hasan Yildirim (Turkey), Gabriel Alziar, Georgios Hadjikyriakou (Cyprus), and Errol Véla (Algeria). We also thank Edouard Le Floc'h, Joël Mathez and Peter A. Schaeffer for helpful discussions and access to the Montpellier Herbarium. We are grateful to Olivier Sparagano for English improvement and to the two anonymous reviewers for further improving the manuscript with their suggestions. This paper is contribution ISE-M no. 2009-087.